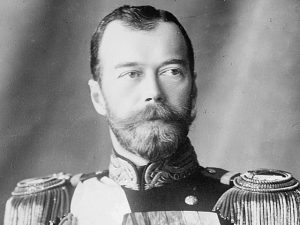

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

No one wanted to go to war with Japan, and it was going to take some work to drum up support for the unpopular war. The Russian government allowed a conference of the zemstvos to take the lead. A zemstvo was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 and carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. The first zemstvo laws went into effect in 1864. After the October Revolution the zemstvo system was shut down by the Bolsheviks and replaced with a multilevel system of workers’ and peasants’ councils…the regional governments instituted by Nicholas’s grandfather Alexander II, in St. Petersburg in November 1904. The demands for reform made at this congress went unmet and more radical socialist and workers’ groups decided to take a different tack.

Things exploded on January 22, 1905, when a group of workers led by the radical priest Georgy Apollonovich Gapon marched to the czar’s Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to make their demands. the imperial forces

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

Leave a Reply