Politics

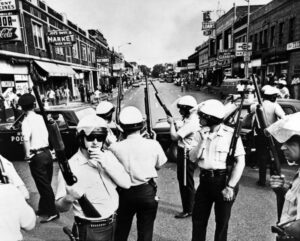

There have been times in the history of our nation, when peace seemed to reign in the land, and then there have been times, when chaos was the word of the day. in 1967, chaos was definitely the word of the day…in Detroit, Michigan, anyway. In 1967, Detroit was a city that was struggling economically, and racially. During that time, vice squad raids, looking for illegal drinking establishments in the city’s poorer neighborhoods were common, and people were in a state of high irritation.

There have been times in the history of our nation, when peace seemed to reign in the land, and then there have been times, when chaos was the word of the day. in 1967, chaos was definitely the word of the day…in Detroit, Michigan, anyway. In 1967, Detroit was a city that was struggling economically, and racially. During that time, vice squad raids, looking for illegal drinking establishments in the city’s poorer neighborhoods were common, and people were in a state of high irritation.

During one particular raid that occurred at 3:35am on Sunday morning, July 23, 1967, the Detroit Police Department moved in against a club that was hosting a party for returning Vietnam War veterans. The early-morning police activity angered a crowd of onlookers, and before long, the situation became explosive. Before long, thousands of people had rushed out onto the street from nearby buildings. The crown began throwing rocks and bottles at the police, who quickly fled the scene. Getting rid of the police, however, didn’t resolve the situation. The crowd began looting on 12th Street, where the club was located, and a number of shops and businesses were completely trashed!!

By sunrise, fires began breaking out and before long, the whole street was on fire. By midmorning, the police were finally called back to the scene, but controlling the crowd proved to be a major struggle. Unfortunately, getting the situation under control proved to be much more difficult than getting it started. The rioting continued all week, in the end, the US Army and the National Guard were called in to stop the worst of it. Five days later, when the bloodshed, burning, and looting ended, 43 people were dead and many more were seriously injured. In all, approximately 1,400 buildings had been burned or ransacked.

Crowds can quickly get out of control, but sometimes the fault lies equally between crowds and police. In this case, the Detroit Police Department was run directly by the mayor, and prior to the riot, Mayor Cavanagh’s appointees, George Edwards and Ray Girardin, worked for reform. Edwards even tried to recruit and promote black police officers in an effort to help quell racial tensions, but in what might be his biggest mistake, he refused to establish a civilian police review board, which the African American population had requested. He was trying to discipline police officers accused of brutality, and in doing so, he turned the police department’s rank-and-file against him. Many whites perceived his policies as “too soft on crime.” The Community Relations Division of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, in a study in 1965 of the police, which was published in 1968, claimed the “police system” was at fault for racism. They blamed the police system was blamed for recruiting “bigots” and reinforcing bigotry through the department’s “value system.” President Johnson’s Kerner

Commission conducted a survey that found that prior to the riot, 45 percent of police working in black neighborhoods were “extremely anti-Negro” and an additional 34 percent were “prejudiced.” I suppose some might say that the fault of the riot was the police, but to a degree, they were doing their jobs too. Maybe it was the way the did it, and the fact that they ran when it got out of hand. Whatever the case may be, the outcome was horrific.

Commission conducted a survey that found that prior to the riot, 45 percent of police working in black neighborhoods were “extremely anti-Negro” and an additional 34 percent were “prejudiced.” I suppose some might say that the fault of the riot was the police, but to a degree, they were doing their jobs too. Maybe it was the way the did it, and the fact that they ran when it got out of hand. Whatever the case may be, the outcome was horrific.

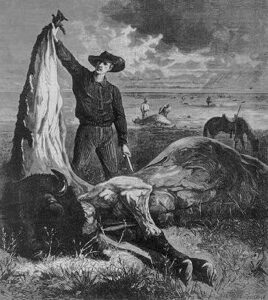

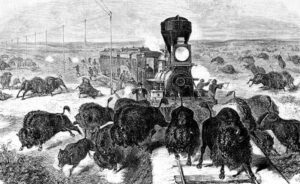

It is amazing to me that the ideas of one person can change the world, a nation, state, or city. Sometimes the changes are good, and sometimes they are horrible. During the early years of the Old West, besides fighting with the American Indians, there were those who felt like the buffalo were a big problem too. General Philip Sheridan said, “Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance.” His idea created a frenzy of hunters, intent on ridding the country of the buffalo. The buffalo, at that time an estimated 50-60 million of them, roamed freely in the Great Plains before white settlers began to push into the vast west in any great numbers. The buffalo were a vital food source for the American Indians hunted them for food and other necessities, and a harmonious ebb and flow between man and beast prevailed.

It is amazing to me that the ideas of one person can change the world, a nation, state, or city. Sometimes the changes are good, and sometimes they are horrible. During the early years of the Old West, besides fighting with the American Indians, there were those who felt like the buffalo were a big problem too. General Philip Sheridan said, “Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance.” His idea created a frenzy of hunters, intent on ridding the country of the buffalo. The buffalo, at that time an estimated 50-60 million of them, roamed freely in the Great Plains before white settlers began to push into the vast west in any great numbers. The buffalo were a vital food source for the American Indians hunted them for food and other necessities, and a harmonious ebb and flow between man and beast prevailed.

That was about to change after the Civil War, as more and more people moved westward. As the migration progressed, new army posts were established, and at the same time came the need for food and supplies for the soldiers. So, the army contracted with local men to supply buffalo meat to feed the troops. Then came the construction workers for the railroad, and a greater need for food. General Sheridan considered the buffalo a nuisance animal, as so was all for the slaughter of the buffalo. The buffalo coats could also supply the army and contractors with buffalo robes that could be used as coats and lap robes when riding in sleighs and carriages. These events put many a man to work as buffalo hunters. Because many people needed work, the offer of work came as a welcome prospect.

Leavenworth, Kansas, soon became a trading center for the buffalo hides, and tanneries found even more, uses for the material. Soon, things such as drive belts for industrial machines and grinding buffalo bones into fertilizer because common practices. In some places, buffalo tongues became a delicacy in fine restaurants. Personally, I would have to call things like at that one…disgusting!! Even though I know that some people like them. Before long the demand was so high that year-round work was available for buffalo hunters.

At the time of this offering, the economy was depressed after the Civil War, so many of the “tough” men decided to earn their living as a buffalo hunter. They had families to support, and so they went out, armed with powerful, long-range rifles. Each individual hunter could kill as many as 250 buffalo a day. Tanneries paid as much as $3.00 per hide and 25¢ for each tongue, which made a nice living for hundreds of men, including Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Pat Garrett, Wild Bill Hickok, and William F Cody, just to name a few. Sadly, the meat wasn’t treated as well. All they wanted were the hides and tongues, so the rest of the edible buffalo meat was often left to rot on the Plains. Such a horrific waste. Over 5,000 hunters and skinners were involved in the trade by the 1880s.

Of course, to the Indians, this horrific slaughter was as heinous a crime as there ever could be. The majestic buffalo, who had often given their lives to supply the tribe with much needed food and blankets were being killed as if it was nothing more than sport. The air took on an almost carnival atmosphere when railroads began to advertise “hunting by rail.” Whenever the trains encountered a herd of buffalo crossing the tracks, it started a shooting spree. The sporting men would shoot hundreds of buffalo for fun, and then the trains would roll away, leaving the dead animals where they fell.

As you would expect, the Indians grew more and more angry and this senseless slaughter. They were, after all, watching their main source of food laying waste on the prairie. Their anger led to more Indian attacks on the White Man, which resulted in US Army retaliation at the height of the Indian Wars. Before long, the US Government decided that they needed to separate the Indians from the rest of “civilization” by placing them on reservations. To force the Indians onto the reservations, they needed to get rid of most of their food source, so US Army aggressively pursued a policy to eradicate the buffalo, which would force them onto reservations in order to survive.

Finally, the Texas Legislature began discussing a bill to protect the buffalo. Of course, General Sheridan defended the buffalo hunters and opposed the bill by saying, “These men have done more in the last two years and will do more in the next year to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well-known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will, but for lasting peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalos are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

Finally, in 1884 the era of the buffalo slaughter ended, and nothing remained of the massive buffalo herds but

piles of bones. By then, there were only about 1,200-2,000 surviving buffalo left in the United States. Through the continuing management efforts, there are currently 500,000 buffalo in the United States, including about 5,000 in Yellowstone and 1,000 in the Black Hills. These days, there are buffalo in every state.

piles of bones. By then, there were only about 1,200-2,000 surviving buffalo left in the United States. Through the continuing management efforts, there are currently 500,000 buffalo in the United States, including about 5,000 in Yellowstone and 1,000 in the Black Hills. These days, there are buffalo in every state.

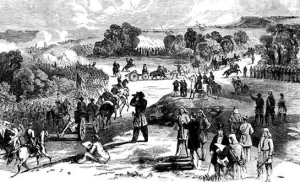

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

Bull Run was the first land battle of the Civil War. It was a battle that was fought at a time when many Americans believed the war would be short and relatively bloodless. They just really didn’t understand how this was going to play out. So, believe it or not, the civilians went out to watch the war, bringing a picnic lunch along with them. If you think about it, bringing the family and a picnic lunch out to watch a battle, had to seem strange, or even insane, and really it was, but many of the civilians were there because they had to be.

While the reporters were there too, for their own selfish reasons, they were quick to condemn the other civilians who were there, calling them frivolous. The Boston Herald published a lengthy, “not-so-funny” comedy poem about the scene. They were making the civilians look reckless. In the poem, HR Tracy describes a story “lacking in glory” about “careless picnickers who heedlessly went out to watch the battle and then ran away, driving over dead and wounded in their carriages.” This kind of public criticism gave rise to the idea of Bull Run as the “picnic battle” but there was more going on. No one really knows exactly how many civilians were there on that day. The recruits in the battle signed up to Lincoln’s army for a 90-day term, because they all thought the war would be over that fast. It’s also hard to be sure how many watchers there were. Many people say men, women and children, but others say it was mostly men.

The people did bring food and even picnic baskets to watch the battle, but it wasn’t exactly like they thought it was a leisurely day out for either spectators or combatants. Picnic food “was more of a necessity than a frivolous pursuit on a Sunday afternoon,” writes Jim Burgess writes for the Civil War Trust. Just getting to Centreville, where the battle was fought, was a seven-hour carriage ride away from Washington, so they had to take food for the journey, because the local Virginians were not going to offer the Union onlookers any kind of hospitality. Some called them a “throng of sightseers” while others mentioned that they were selling pies and other edibles. I think the whole thing was a misunderstanding of epic proportions. Unfortunately, after the  people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

The reality was that the battle wasn’t just a spectator sport. It was important politically, so the politicians attended. It was important socially, so the journalists attended. It was also an opportunity to sell food, so the food vendors attended. In the end, it was really a circus, and once it was over, there was no one left who innocently thought that this war would end in 90 days, and no one left that thought there would be little bloodshed.

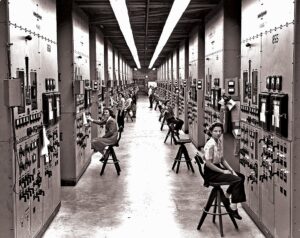

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

They were actually monitoring the manufacturing of enriched uranium that was to be used to make the “Little Boy” atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing to be carried out on August 6, 1945. The Manhattan Project, which was established to develop nuclear weapons, required uranium-235 (U235), the fissionable isotope of uranium. The vast majority of uranium that is mined from the ground is uranium-238. Only about while only 0.7% is U235. The scientists in charge of the project developed several processes for separating the isotopes of uranium, including electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion.

“The Y-12 factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to house 1,152 calutrons, a machine used for isotope separation. The word “calutron” is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron. Calutrons, a variation on mass spectrometers, work by combining uranium with chlorine to make uranium tetrachloride, which is then ionized and put in a vacuum chamber with a magnetic field. When the charged particles move through the magnetic field, they move in a curve, the radius of which is proportional to the mass of the particles. The two isotopes differ in mass by about 1% and can thus be separated.”

The process of separating the U235 Uranium out of the oar was relatively simple, but it still required people to constantly monitor the calutrons. Unfortunately, during World War II, many of the men were fighting. That left a shortage of labor. There simply weren’t enough scientists to operate all of the calutrons. So, the government recruited farm girls to operate the calutrons instead. The main reason for using the young women, was that they were readily available, accustomed to hard work. A stipulation of their employment was that they were not to ask excessive questions, and they had to be loyal and docile. I’m sure these women thought they were doing something top secret and all, but I don’t think they had any idea of the gravity of this project. Lives were on the line, and lives would be lost. Still, they didn’t know that, so I suppose their superiors assumed it would let them sleep at night. I suppose it did. These women honestly didn’t know what they were a part of…some until years later. They would never forget what they did, and they would always wonder if it was right or wrong.

The Tennessee Eastman Company, which ran the Y-12 site, recruited around 10,000 local women between 1943 and 1945. They hired train operators with only a high school education, and they used a large local advertising campaign to recruit workers. One ad read, “When you’re a grandmother you’ll brag about working at Tennessee Eastman.” Word of mouth brought in several other workers. Of course, in hard times, a big motivator was the money being paid. Plus, these women were patriots, and this work was for the war effort. They were trained for three weeks, and they went to work.

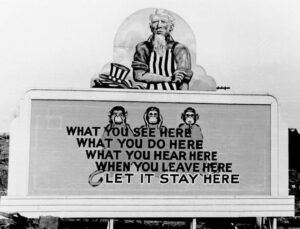

The Tennessee Eastman Company was loyal to the cause. They put a billboard on the premises reading “What you see here / what you do here / what you hear here / when you leave here / let it stay here,” with three wise monkeys to demonstrate “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Another billboard at the Oak Ridge location,  encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

The work these women did was not what would be considered labor intensive by any means. The women sat on high stools for 8-hour shifts, seven days per week, “monitoring gauges and adjusting knobs to keep the needles where they were supposed to be and recording readings.” The knobs the women were adjusting were simply labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for. What they were taught was that “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you’d get the Q and R you wanted.” Okay…whatever that meant. All they knew was that they had to make sure the machine remained at the correct temperature. That was vital and if it got too hot, they used liquid nitrogen to cool it down. If the needles reached a point where they could not control them, they had to call someone else to come help…immediately!!!

Former Calutron Girl Wynona Arrington Butner said, “We all wore little fountain-pen-sized dosimeters. Part of signing out of the plant was to check the amount of radiation that you had absorbed every day.” Civilian workers paid $2.50 per month (single) or $5.00 per month (family) for medical insurance. I don’t know if they understood what radiation could do to them or not, but if they did, they would know that the wages paid and even the insurance help, was probably not enough.

Some Calutron Girls had more of a sense of what they were working on than others. Butner, who had some training in chemistry, said she and others with a similar background had some sense of what they were doing. They knew they were producing “the Product,” and they guessed it was somewhere near the bottom of the periodic table. Willie Baker, on the other hand, said, “Even when somebody let it slip that we were building a bomb, I didn’t know what they meant. I was just a country girl. I had no understanding of what an atomic bomb was.” Later, I’m sure the gravity of the work she did, weighed heavily on Baker.

Over two years, the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 140 pounds of U235. This was enough to make the first atomic bomb. By December 1945, enough uranium for a second Little Boy was available. Then, it all hit these women, because on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped the first bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima, Japan, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on. I can’t imagine how they must have felt. When they heard the news, some women were working, while others were in their dorm rooms. Someone came and told them that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan, and everyone there had played a part in making it. Yes, it was the enemy, and death happens in war. Nevertheless, the Calutron Girls had mixed feelings about their part in the bomb. Ruth Huddleston said she was “really happy at the time, because her boyfriend was stationed in Germany, and this would bring him back.” Still, it bothered her that she had a part in killing so many people, but she accepted that “if the bomb hadn’t been dropped, then probably more people would have been killed. …But even today, if I think too much about it, it bothers me.” Butner had a similar experience, because at the time, she was happy that the war was over and people she knew in the service could come  home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

Most of the Calutron Girls are gone now, but those who remain, such as Huddleston, regularly shared their stories with the public, often alongside Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith. The women are the subject of the nonfiction book “The Girls of Atomic City” by Denise Kiernan and the novel “The Atomic City Girls” by Janet Beard. I’m sure that many of these women suffered nightmares over the work they did, but did not know they were doing. While I know they suffered much anxiety over that, I hope they also know that we are so grateful for their service to this great nation.

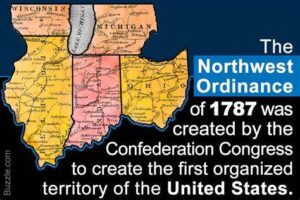

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

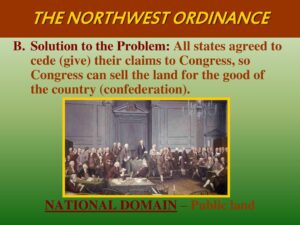

That left the United States with a kind of dilemma, since they wanted to make sure these new states were run in the way they had originally designed. So, on July 13, 1787, Congress enacts the Northwest Ordinance, to structure the settlement of the Northwest Territory. Since the formation of new states was a new venture for  the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

That said, in 1781, the state of Virginia began the process by ceding its extensive land claims to Congress. That bold move made other states more comfortable in doing the same. Thomas Jefferson first proposed a method of incorporating these western territories into the United States in 1784. His plan was to basically turn the territories into colonies of the existing states. Since each state was to have their own constitution, the ten new northwestern territories would select the constitution of an existing state that closely aligned with their own values. Once that process was complete, the new territory (colony) had to wait until its population reached 20,000 to join the confederation as a full member. That process made Congress nervous, because they feared that the new states…10 in the Northwest as well as Kentucky, Tennessee and Vermont…would quickly gain enough power to outvote the old ones, so Congress never passed Thomas Jefferson’s proposal.

It would be three more years before the Northwest Ordinance which proposed that “three to five new states be created from the Northwest Territory. Instead of adopting the legal constructs of an existing state, each territory would have an appointed governor and council. When the population reached 5,000, the residents could elect their own assembly, although the governor would retain absolute veto power. When 60,000 settlers  resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

The last part angered the pro-slavery Southerners, but they were willing to go along with this because they hoped that the new states would be populated by white settlers from the South. They believed that although these Southerners would have no enslaved workers of their own, they would not join the growing abolition movement of the North. Of course, we all know how that played out.

Every era has its trends. And the affluent sector of society is far more likely to go for the odd trends, to prove that they are high society, than the everyday guy. One such trend, that took place in the second half of the 18th century, was the wearing of the wig. It was considered a major status symbol. Nevertheless, by 1800, short, natural hair was all the rage again. That seems to be the problem with trends. Sometimes, they barely get started and suddenly they are over. The trend was toward the wearing of curly white wigs by gentlemen in the 18th century as part of their everyday look. Of course, many people will remember George Washington, with a nod of their head, but the reality is that George Washington never wore a wig. That was his real hair, with the addition of white powder. He, unlike many other men of that era, had a head full of red hair. He powdered it, because will he had plenty of hair to look like a wig, it was red. When Gilbert Stuart, the famous portraitist, painted the Founding Fathers, he depicted five of the first six Presidents with pure white hair. Unlike Washington, the next four Presidents, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe did wear wigs, so his depiction of them was correct, and Washington wore his hair in that style, so he could look like he wore a wig without the expense of one.

Every era has its trends. And the affluent sector of society is far more likely to go for the odd trends, to prove that they are high society, than the everyday guy. One such trend, that took place in the second half of the 18th century, was the wearing of the wig. It was considered a major status symbol. Nevertheless, by 1800, short, natural hair was all the rage again. That seems to be the problem with trends. Sometimes, they barely get started and suddenly they are over. The trend was toward the wearing of curly white wigs by gentlemen in the 18th century as part of their everyday look. Of course, many people will remember George Washington, with a nod of their head, but the reality is that George Washington never wore a wig. That was his real hair, with the addition of white powder. He, unlike many other men of that era, had a head full of red hair. He powdered it, because will he had plenty of hair to look like a wig, it was red. When Gilbert Stuart, the famous portraitist, painted the Founding Fathers, he depicted five of the first six Presidents with pure white hair. Unlike Washington, the next four Presidents, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe did wear wigs, so his depiction of them was correct, and Washington wore his hair in that style, so he could look like he wore a wig without the expense of one.

Trends weren’t the only reason for the wigs, however. In the 17th century, hairlines were an important aspect of fashion. It was thought that a “well-bred man” would have a good hairline. Unfortunately, in the pre- antibiotics world, syphilis was on the rise in Europe. It ultimately affected more Europeans than the Black Plague. Without antibiotics, people afflicted with syphilis suffered all the effects, including sores and patchy hair loss. That became a huge problem for men of status. Because of that, wigs were commonly used to cover up hair loss, and it wasn’t until two Kings started to lose their hair, that their use became widespread. King Louis XIV of France experienced hair loss at the early age of 17, and he hired 48 wigmakers to help combat his thinning locks. His English cousin, King Charles II, began wearing wigs a few years later, when his hair began to grey prematurely. Both conditions were indications of syphilis. A fashion was born, as courtiers started wearing wigs, and the trend trickled down to the merchant class. Of course, as we all know syphilis was not the only reason for balding, nevertheless, it could have been a bad thing to have people assuming.

antibiotics world, syphilis was on the rise in Europe. It ultimately affected more Europeans than the Black Plague. Without antibiotics, people afflicted with syphilis suffered all the effects, including sores and patchy hair loss. That became a huge problem for men of status. Because of that, wigs were commonly used to cover up hair loss, and it wasn’t until two Kings started to lose their hair, that their use became widespread. King Louis XIV of France experienced hair loss at the early age of 17, and he hired 48 wigmakers to help combat his thinning locks. His English cousin, King Charles II, began wearing wigs a few years later, when his hair began to grey prematurely. Both conditions were indications of syphilis. A fashion was born, as courtiers started wearing wigs, and the trend trickled down to the merchant class. Of course, as we all know syphilis was not the only reason for balding, nevertheless, it could have been a bad thing to have people assuming.

The wigs were called perukes. They were convenient because they were relatively easy to maintain, only needing to be sent to a wigmaker for a delousing. I’m sure that the powder, often flour, attracted every kind of bug imaginable. As wigs became more popular, they became a status symbol for people to “flaunt their wealth. An everyday wig cost 25 shillings, a week’s worth of wages for a common Londoner. The term ‘bigwig’ stems from this era, when British nobility would spend upwards of 800 shillings on wigs. In 1700, 800 shillings was approximately £40 (about $50 today) which when calculated for inflation, comes out to around £8,297 or $10,193 in today’s currency.”

Men weren’t the only ones to buy into the trend. Women, like Marie Antoinette were famous for their wigs. Military officers, especially in the British Army, also wore wigs. Some officers wore wigs, but only very specific military plait wigs, not the wigs that were bought and worn by those in high society. According to Revolutionary War Journal, “perukes were hot and heavy, extremely expensive, and constantly infected with bugs,” which was

problematic for military use. In 1706, the military officers mostly used Campaign wigs, particularly the Ramillies wig, which was named after a British victory during the War of Spanish Succession. It was a short pigtail, or “queue” tied near the scalp and at the bottom of the plait. While these queues were originally fashioned from a soldier’s real hair, fake queues quickly became the norm. Nevertheless, the wigs were hot and uncomfortable, they were often bug infested, and by 1800, people were over it. That part hasn’t changed much over the years either. As anyone who wore a wig after Chemotherapy can tell you, at some point, most people just embrace the bald, and some men even shave their heads at the first sign of balding. Another was of embracing the bald.

problematic for military use. In 1706, the military officers mostly used Campaign wigs, particularly the Ramillies wig, which was named after a British victory during the War of Spanish Succession. It was a short pigtail, or “queue” tied near the scalp and at the bottom of the plait. While these queues were originally fashioned from a soldier’s real hair, fake queues quickly became the norm. Nevertheless, the wigs were hot and uncomfortable, they were often bug infested, and by 1800, people were over it. That part hasn’t changed much over the years either. As anyone who wore a wig after Chemotherapy can tell you, at some point, most people just embrace the bald, and some men even shave their heads at the first sign of balding. Another was of embracing the bald.

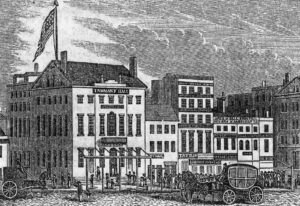

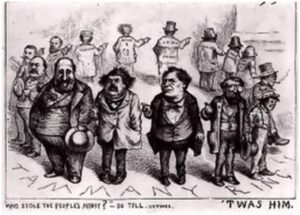

Soldiers are trained to obey orders without thought of the moral aspects the order might have carried. Nevertheless, not every order is a good one. Still, there have been a number of times when disobeying an order was very questionable, such as the order given to General Daniel Sickles at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician with ambitions of becoming president. Tammany Hall, which was also known as the Society of Saint Tammany, the Sons of Saint Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. In New York City and New York state politics, and it had become the main local political machine of the Democratic Party. The Tammany Hall politicians focused on bringing immigrants, most notably the Irish, into American politics from the 1850s, and into the 1960s. Tammany Hall politicians virtually controlled the Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years following the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854. These politicians used their patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders, and after 1850, the vast majority were Irish Catholics due to mass immigration from Ireland during and after the Irish Famine of the late 1840s.

Soldiers are trained to obey orders without thought of the moral aspects the order might have carried. Nevertheless, not every order is a good one. Still, there have been a number of times when disobeying an order was very questionable, such as the order given to General Daniel Sickles at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician with ambitions of becoming president. Tammany Hall, which was also known as the Society of Saint Tammany, the Sons of Saint Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. In New York City and New York state politics, and it had become the main local political machine of the Democratic Party. The Tammany Hall politicians focused on bringing immigrants, most notably the Irish, into American politics from the 1850s, and into the 1960s. Tammany Hall politicians virtually controlled the Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years following the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854. These politicians used their patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders, and after 1850, the vast majority were Irish Catholics due to mass immigration from Ireland during and after the Irish Famine of the late 1840s.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Sickles raised a brigade with himself as its commander, hoping to improve his reputation, which had suffered greatly when he murdered his wife’s lover. On July 2, Sickles’s III Corps was ordered to defend a portion of Cemetery Ridge. This area included Little Round Top, and it was a central position between two other divisions. It seemed like the perfect strategy, but Sickles, feeling that the lay of the land made his position indefensible, asked Major General George S Meade for permission to advance three-quarters of a mile to the Emmitsburg Road. When Meade refused, Sickles ended up advancing, against a direct order, to the forward position anyway. That shift of position left his unit vulnerable to flanking attacks and also left Little Round Top undefended. Clearly, Sickles didn’t understand the strategies of war that were well known to Major General Meade. I guess soldiers are promoted for a reason.

Sickles was forced to retreat and lost almost 40% of his force in the Confederate attack that followed. After Sickles had abandoned his post, the task of defending Little Round Top fell to the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, V corps, and in fact made famous the 20th Maine brigade, under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain. In the end, they famously managed to repel the Confederate advance, but the victory would not have needed the heroics if Sickles had stayed at his post. Of course, typical of those who rebel and ignore the orders given, Sickles

maintained to the end of his days that his insubordination helped the Army of the Potomac survive the day’s assaults. It was a crazy declaration, but I guess it helped him sleep at night. There are those on both sides of the coin on that one, but in the end, the disobedience cost him much more than he might have imagined, since he was never the president.

maintained to the end of his days that his insubordination helped the Army of the Potomac survive the day’s assaults. It was a crazy declaration, but I guess it helped him sleep at night. There are those on both sides of the coin on that one, but in the end, the disobedience cost him much more than he might have imagined, since he was never the president.

In the world of criminal justice, you might think that the punishment should fit the crime, and in that case, murder should get the death penalty. Of course, no one would dispute the fact that there could be extenuating circumstances. Sometimes, the murder was accidental, or the perpetrator was truly insane, whether temporarily or permanently. Those aren’t the common reasons for murder though. Nevertheless, there are those who believe that there shouldn’t be a death penalty for any reason. They call it cruel and unusual punishment, even if the perpetrator is not sorry for their crime, but the reality is that the killer took a life, and that should usually bring the death penalty.

In the world of criminal justice, you might think that the punishment should fit the crime, and in that case, murder should get the death penalty. Of course, no one would dispute the fact that there could be extenuating circumstances. Sometimes, the murder was accidental, or the perpetrator was truly insane, whether temporarily or permanently. Those aren’t the common reasons for murder though. Nevertheless, there are those who believe that there shouldn’t be a death penalty for any reason. They call it cruel and unusual punishment, even if the perpetrator is not sorry for their crime, but the reality is that the killer took a life, and that should usually bring the death penalty.

Over the years, there have been multiple pushes by activist groups that were against the death penalty under any circumstances. Finally, in the case of Furman v. Georgia, the US Supreme Court ruled by a vote of 5-4 that capital punishment, as it is currently employed on the state and federal level, is unconstitutional. In that case, the majority of the judges held that, “in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, the death penalty qualified as  ‘cruel and unusual punishment,’ primarily because states employed execution in ‘arbitrary and capricious ways,’ especially in regard to race.” That decision was the first time that the nation’s highest court had ruled against capital punishment. In the case, they didn’t say that the death penalty, in and of itself, was unconstitutional, but rather left room for new legislation that could make death sentences constitutional again. These included the development of standardized guidelines for uries that decide sentences. Because there was room for changes to the way things were done, the decision was not an outright victory for opponents of the death penalty.

‘cruel and unusual punishment,’ primarily because states employed execution in ‘arbitrary and capricious ways,’ especially in regard to race.” That decision was the first time that the nation’s highest court had ruled against capital punishment. In the case, they didn’t say that the death penalty, in and of itself, was unconstitutional, but rather left room for new legislation that could make death sentences constitutional again. These included the development of standardized guidelines for uries that decide sentences. Because there was room for changes to the way things were done, the decision was not an outright victory for opponents of the death penalty.

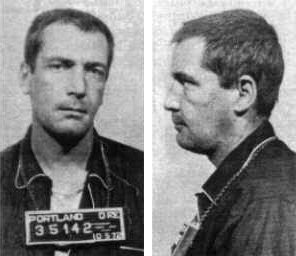

Finally, in 1976, with 66 percent of Americans still supporting capital punishment, the Supreme Court acknowledged that progress had been made in jury guidelines and reinstated the death penalty under a “model of guided discretion.” Then in 1977, Gary Gilmore, a career criminal who had murdered an elderly couple simply because they would not lend him their car, was the first person to be executed since the end of the ban. Gilmore was defiant…facing a firing squad in Utah. His last words to his executioners before they shot him through the heart were, “Let’s do it.” Gilmore was one of those criminals who had no respect for life…not even his own. He was a brutal killer, and he died a justified death. He wasn’t brave at the time of his death. He was  just stubborn and defiant. I suppose he might have seen himself as a martyr, but the reality was that he was simply a cold-blooded criminal, who got what he deserved…the same thing he gave to his victims. Some of his victims even cooperated, but it made no difference. He killed them anyway. He received exactly what he should have…and he wanted it too. During the time Gilmore was on death row awaiting his execution, he attempted suicide twice; the first time on November 16 after the first stay was issued, and again one month later on December 16. On the day of his execution, he was smiling as he was led to the chair the strapped him to for his execution. Gilmore was put to death on January 17, 1977.

just stubborn and defiant. I suppose he might have seen himself as a martyr, but the reality was that he was simply a cold-blooded criminal, who got what he deserved…the same thing he gave to his victims. Some of his victims even cooperated, but it made no difference. He killed them anyway. He received exactly what he should have…and he wanted it too. During the time Gilmore was on death row awaiting his execution, he attempted suicide twice; the first time on November 16 after the first stay was issued, and again one month later on December 16. On the day of his execution, he was smiling as he was led to the chair the strapped him to for his execution. Gilmore was put to death on January 17, 1977.

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

Scapa Flow was a naval base in the Orkney Islands in Scotland. When the German ships arrived, they had full crews and in all, there were more than 20,000 German sailors aboard, the number of sailors was reduced in the ensuing months. When the full fleet was at Scapa Flow, there were 74 ships there during negotiations between the Allies and Germany over a peace treaty that would become Versailles. The discussion was about what to do with the ships, since they didn’t really want Germany to have a full fleet ready, should they decide to wage war again. The French and Italians wanted a portion of the fleet, but the British wanted them destroyed. They were concerned about their own naval superiority, should the ships be distributed among the other Allied nations.

The Germans didn’t want their ships in the hand of their enemies, so Admiral Ludwig von Reuter began to prepare for the scuttling in May 1919, after hearing about the potential terms of the Versailles Treaty. Shortly before the treaty was signed on June 21, Reuter sent the signal to his men. The men began opening flood valves, smashing water pipes, and opening sewage tanks. As the scuttle was taking place, nine German crew members who abandoned ship and attempted to come ashore were shot by British forces. As the ships were being scuttled, the intervening British guard ships were able to beach some of the ships. In all, 52 of the 74 ships were sunk. While he wouldn’t say so out loud, British Admiral Wemyss was delighted that the ships were

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

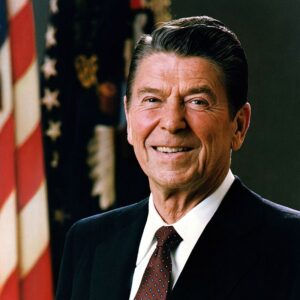

As events from the past get further and further from the present, it’s easy to forget all about them, and for the younger generations…well, they never knew about them, unless they learned about them in history class. In my opinion and the opinion of many conservatives, one of the greatest presidents of all time, was President Ronald Reagan. As a young man, I’m sure no one would have expected that he would even pe president. He was, after all, an actor, and not a politician. Nevertheless, he stepped out of that role, and became first the governor of California, and later the President of the United States, and it was at a pivotable time in history that he was the president.

As events from the past get further and further from the present, it’s easy to forget all about them, and for the younger generations…well, they never knew about them, unless they learned about them in history class. In my opinion and the opinion of many conservatives, one of the greatest presidents of all time, was President Ronald Reagan. As a young man, I’m sure no one would have expected that he would even pe president. He was, after all, an actor, and not a politician. Nevertheless, he stepped out of that role, and became first the governor of California, and later the President of the United States, and it was at a pivotable time in history that he was the president.

Our nation was in the middle of the Cold War, which had really fired up in 1945, at the end of World War II, and continued on until 1991. During that time, we experienced the Iran Hostage Crisis on November 4, 1979, that lasted until January 20, 1981, spanning a total of 444 days. The hostage rescue finally came after President Reagan ordered it, when he became president. He was not afraid to act. He saw something that was unacceptable, and he remedied it…just hours after his inaugural speech. It shouldn’t have taken 444 days to

free these hostages, but until President Reagan stepped in, there was just one attempt, and it failed. The 52 hostages felt forgotten, until President Reagan and the men he sent in, rescued them.

free these hostages, but until President Reagan stepped in, there was just one attempt, and it failed. The 52 hostages felt forgotten, until President Reagan and the men he sent in, rescued them.

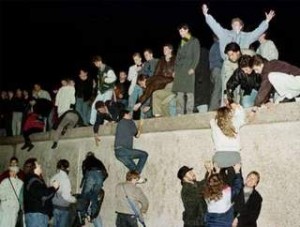

During President Reagan’s two terms in office, he worked tirelessly to change many things for the better. He hated tyranny, no matter what country it invaded. He looked at the Berlin Wall for what it was tyranny. Those people had been taken hostage and separated from their friends and family for long enough. In one of his most well-known speeches, President Reagan called for the tyranny to end, when on June 12, 1987, he challenged Soviet Leader Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall,” which had long been a symbol of the repressive Communist era in a divided Germany. Of course, the wall didn’t come down immediately, and in fact, it wasn’t until November 9, 1989, that it actually came down.

President Reagan was at the helm when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded just 73 seconds after liftoff. It was a tragic event in the space program, and the people of this nation need to be consoled. President Reagan was just the man to give this nation the support it needed. His speech that day was supposed to have been the 1986 State of the Union speech, but President Reagan knew this was more important, so he delayed the State of the Union speech, and instead gave a speech to console us saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, I’d planned to

speak to you tonight to report on the state of the Union, but the events of earlier today have led me to change those plans. Today is a day for mourning and remembering.” He concluded his speech saying, “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.'” President Reagan was truly a great president. President Reagan served two terms as president, from 1981 to 1989. He died on June 5, 2004, at age 93.

speak to you tonight to report on the state of the Union, but the events of earlier today have led me to change those plans. Today is a day for mourning and remembering.” He concluded his speech saying, “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.'” President Reagan was truly a great president. President Reagan served two terms as president, from 1981 to 1989. He died on June 5, 2004, at age 93.