In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

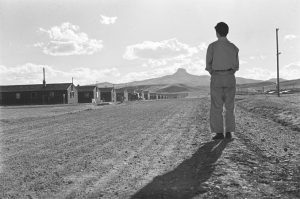

It was decided that, because their loyalties could not positively be confirmed, the Japanese immigrants needed to be rounded up and put in concentration camps. I suppose this might have seemed similar to what the Germans did to the Jewish people, but the Japanese people were not murdered in the camps, like the Jews were. And so it came to be that the people of Japanese descent from Oregon, Washington and California were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Park County, Wyoming, by the executive order of President Franklin Roosevelt. The prisoners were held at the camp from August 12, 1942 to November 10, 1945, which was actually two months after the end of the war with Japan. The camp was populated with 10,000 people at its largest, making it the third largest town in the state at the time.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like for those Japanese immigrants to be held in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center for as much as 2 years and 3 months. Of course, the illegal immigrants of our time immediately came to my mind, but there is a difference between these people and the illegal immigrants of today. These people were here legally, and most of them had already become citizens. Unfortunately, that did not calm the worried minds of the rest of the people of the United States. Our nation had been attacked, and the attackers looked just like the Japanese immigrants. Precautions had to be taken. I’d like to think that if it were me, in that position, that I would understand why this was happening, but I’m not so sure I would. After all, these people were not criminals. They were hard working Americans, and yet they were for a time…the enemy, or possibly the enemy.

Unfortunately, like many prior immigrant groups, the Japanese faced discrimination. Things aren’t always fair, and people aren’t always treated properly. Starting in the early 20th century, Japanese immigrants, as well as Chinese immigrants, were targeted by Alien Land Laws in western states including Wyoming. These laws prevented the Asian immigrants from buying land. In 1924, the United States Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act, which all but cut off new immigration from Asia. In response, Japanese Americans formed organizations such as the Japanese American Citizens’ League to help address their shared challenges. Despite  the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

The Heart Mountain facility consisted of 450 barracks, each containing six apartments, when the first internees arrived on August 12, 1942. The largest apartments were simply single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet. The barracks were covered with tar paper. While each unit was eventually outfitted with a potbellied stove, none had bathrooms. The people all used shared latrines. None of the apartments had kitchens. The residents ate their meals in mess halls. When the people first arrived, a barbed-wire fence to surround the camp was not yet complete. The internees protested the construction of this barrier and caused further work to be delayed. In November 1942, they submitted a petition containing 3,000 signatures to the War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Meyer. The fence was completed by December, however, and further emphasized the sense of confinement among the internees. Shortly after the construction of the fence, 32 boys were arrested for sledding in the hills beyond the boundary. In response to the perceived overreaction on the part of the camp administration, Rikio Tomo, a Heart Mountain internee, placed an editorial in the Heart Mountain Sentinel asking for clarification about the internees’ citizenship status and constitutional freedoms. Schools were built at Heart Mountain, including a high school, to accommodate the children. These schools served students from elementary school through high school. Roughly 1500 students attended Heart Mountain High School, which included grades 8-12.

The internees provided most of the labor required to run the Heart Mountain camp, while WRA administrators oversaw its general operations. Wages ranged from $12 per month for unskilled labor to $19 per month for skilled labor, including teachers for the schools and doctors in the camp hospitals. In addition, Heart Mountain internees also worked as manual laborers on farms and ranches in Wyoming and nearby states from Nebraska to Oregon. The WRA administrators encouraged activities emphasizing American civics, such as scouting and adult English classes, as part of what they saw as an Americanization process. Committees composed initially of American-born internees provided much of the day-to-day governance of the camps. While these groups provided some measure of self-determination, they disrupted the generational hierarchy. American-born adults in their 20s and 30s were given a higher political status within the camps than their Japanese-born parents.

In 1943, General George Marshall approved the creation of the Japanese-American combat unit. As a result of the low turnout, the War Department extended the draft to the camps. It was decided that while they were not free to go where they chose, these people were needed to serve their country, so a draft was instituted. After they were drafted into the U.S. Army, soldiers from Heart Mountain occasionally returned to visit their families who were still held there. Somehow that doesn’t seem quite fair to me, and many of the prisoners agreed. They thought they should have been given their constitutional rights back before they were drafted. The organization of draft resistance distinguished Heart Mountain from the other relocation centers. The plan, which was given the endorsement of President Roosevelt, was to create an all-Japanese regiment, consisting of soldiers from a previously existing Hawaiian unit and volunteers from the camps. The response from within the camps fell far short of expectations, partly because of a loyalty questionnaire distributed by the WRA. The WRA form was used to determine eligibility for military service and permanent leave. Many of the questions were considered intrusive by prisoners. Others were not as straightforward as the WRA probably intended. Instead of serving as a neutral tool to determine someone’s suitability for service, the questionnaire further alienated many the men. To me it seems that the WRA was somehow not aware of how racist the entire situation really was. For example, question 27 asked about a person’s willingness to serve in the military. For

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

One Response to Heart Mountain Life