World War II

When we think of the weapons of warfare, we think of guns, planes, tanks, and such, but there are weapons of warfare that while seemingly far less lethal, are still deadly…in other ways. Economic warfare is something I would never have considered, even though it makes perfect sense. The Germans in World War II thought of every possible weapon, or very close to it. If a nation has no money to bankroll a war, they are very likely going to lose. That was the position that Germany wanted to put Great Britain in during World War II. They decided on an age-old plan…if you’re a criminal that is. Counterfeiting money to tank the economy.

When we think of the weapons of warfare, we think of guns, planes, tanks, and such, but there are weapons of warfare that while seemingly far less lethal, are still deadly…in other ways. Economic warfare is something I would never have considered, even though it makes perfect sense. The Germans in World War II thought of every possible weapon, or very close to it. If a nation has no money to bankroll a war, they are very likely going to lose. That was the position that Germany wanted to put Great Britain in during World War II. They decided on an age-old plan…if you’re a criminal that is. Counterfeiting money to tank the economy.

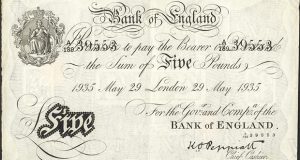

The year was 1942 and for the purpose of artificially causing inflation of the British pound, leading to the economic collapse of the competition, while simultaneously funding some of their own projects, the production of the British “White Notes” was about to start. It would not start in Britain, however. These “White Notes” would be made behind the gates of Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The Germans decided to begin counterfeiting British banknotes. These tactics were considered particularly wrong by the German soldiers themselves, basically sneaky and unprofessional. However, soon after World War II, it became common practice for different countries to counterfeit the currency of their opposition in times of war. Evil knows no bounds.

The first attempt at counterfeiting, known as Operation Andrew, failed because of disagreements between top brass inside of the Nazi Party. Friederich Walter Bernhard Krueger was placed in charge of Germany’s second attempt at counterfeiting British notes. The second operation’s codename was Bernhard because that is what Krueger was called. In preparation for the production, Bernhard assembled a team of about 140 men/prisoners. Some historians have suggested that it was as many as 300. These men were told they would receive better treatment and special perks like radio, newspapers, warm barracks, if they participated in the operation. The men had nothing to lose. All they had to do was counterfeit 400,000 British banknotes a month.

After a year of hard work, and the prisoners finally successfully counterfeited the British White Note. By 1945, conservative estimates figure 70,000,000 notes were printed by the inmates. It was a cache worth upwards of £100,000,000. In order to complete this herculean task, the team of counterfeiters studied vast quantities of authentic White Notes. They broke this massive task up into seven smaller tasks, each one seemingly more difficult than the last. “These tasks included: Discovering secret security marks, Engraving the vignette, Perfecting the paper, Creating identical ink, Solving the serial numbering system, Re-creating the signatures, dates and places of origin, and Printing the notes. The men found no fewer than 150 different security marks hidden on the White Notes. There were intentional minor defects and flaws that the Bank of England incorporated as anti-counterfeiting devices. To make things even harder, these security devices were different for each denomination. Nonetheless, in short order, the counterfeit team produced a plate for each denomination: £5, £10 £20 and £50.” The plan was coming together and soon they were ready to execute it.

The plan was to fly over and drop the counterfeit money from the planes. Once it was laundered and in the hands of the people, they could spend it and because there was no real backing for the money, the economy would tank. The operation went on for a time, but with the late February and early March 1945 advance of the Allied armies, all production of notes at Sachsenhausen ceased. The equipment and supplies were packed and transported, with the prisoners, to the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Austria, arriving on 12 March.

They had to hide the evidence. They didn’t give up on the process, however. Shortly afterwards Krüger arranged a transfer of the equipment to the Redl-Zipf series of tunnels so production could be restarted. The order to resume production was soon rescinded, however, and the prisoners were ordered to destroy the cases of money they had with them. The equipment and any money not burned was loaded onto trucks and sunk in the Toplitz and Grundlsee lakes.

They had to hide the evidence. They didn’t give up on the process, however. Shortly afterwards Krüger arranged a transfer of the equipment to the Redl-Zipf series of tunnels so production could be restarted. The order to resume production was soon rescinded, however, and the prisoners were ordered to destroy the cases of money they had with them. The equipment and any money not burned was loaded onto trucks and sunk in the Toplitz and Grundlsee lakes.

Our enemies really depend on the war we are in. In World War II, Russia was on the side of the United States. While they might not have really been our ally, they weren’t really our enemy either, so I guess they were our “frienemy.” In reality, they were in just as much danger as any other member of the Allies. Germany had made a deal with them, but then invaded them anyway. World War II was a fear-filled time. It was a hard-fought war, against terrible enemies. There were times that it looked like Hitler would win, but in the end, he did not, and as far as history knows, he committed suicide, along with his wife, Eve Braun Hitler, who married him the day before.

Our enemies really depend on the war we are in. In World War II, Russia was on the side of the United States. While they might not have really been our ally, they weren’t really our enemy either, so I guess they were our “frienemy.” In reality, they were in just as much danger as any other member of the Allies. Germany had made a deal with them, but then invaded them anyway. World War II was a fear-filled time. It was a hard-fought war, against terrible enemies. There were times that it looked like Hitler would win, but in the end, he did not, and as far as history knows, he committed suicide, along with his wife, Eve Braun Hitler, who married him the day before.

The people of the Soviet Union heard on the radio on May 9, 1945, at 1:10am, that Nazi Germany had signed the act of unconditional surrender. That surrender ended the USSR’s fight on the Eastern Front of World War II, or the Great Patriotic War as the Soviets called it. That war had been devastating consequences…according to official data, the state lost more than 26 million people. It was a great day for Russia and for the world. Hitler was dead, and the world could move forward and begin to heal. It was truly a rare case of an indestructible victory over its worst enemy, and the people of the state began a traditional method of celebration…drinking vodka and toasting to their victory.

The party began that day, May 9, 1945, and continued without ceasing for about 22 hours. People were so excitedly celebrating that they really didn’t think about their condition. They went outside in their pajamas,  embraced, and wept with happiness. They didn’t care if they were in their pajamas, they were elated, and they partied. In fact, even non-drinkers began to drink. The party came to a screeching halt 22 hours later when the wartime deficiency of vodka, led to a unique situation. The party was in full swing, and when Joseph Stalin stepped up to address the nation in honor of the victory, the population had drunk all the vodka reserves in the country. I don’t think people really cared at that point what they toasted with. They would gladly lift a glass of water to cheer the victory. Nevertheless, how often does an entire nation run out of liquor…unless the nation is in prohibition, that is?

embraced, and wept with happiness. They didn’t care if they were in their pajamas, they were elated, and they partied. In fact, even non-drinkers began to drink. The party came to a screeching halt 22 hours later when the wartime deficiency of vodka, led to a unique situation. The party was in full swing, and when Joseph Stalin stepped up to address the nation in honor of the victory, the population had drunk all the vodka reserves in the country. I don’t think people really cared at that point what they toasted with. They would gladly lift a glass of water to cheer the victory. Nevertheless, how often does an entire nation run out of liquor…unless the nation is in prohibition, that is?

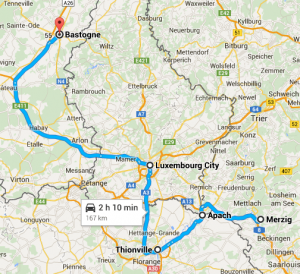

The Battle of the Bulge has been a brutal, hard-fought battle. The soldiers were tired, cold, and hungry; and all they wanted was a night off to recharge. That was not to be. They had more pressing matters to attend to, and the fate of the free world might just depend on their success. The Germans had achieved a total surprise attack on the Belgian town of Bastogne, on the morning of December 16, 1944, due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance because to bad weather. The American forces, specifically the US 101st Airborne Division bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties of any operation during the war. The town was vital to the Germans, because it would open up a valuable pathway further north for German expansion. The siege had to be stopped, and the 101st Airborne Division needed help to do it.

The Battle of the Bulge has been a brutal, hard-fought battle. The soldiers were tired, cold, and hungry; and all they wanted was a night off to recharge. That was not to be. They had more pressing matters to attend to, and the fate of the free world might just depend on their success. The Germans had achieved a total surprise attack on the Belgian town of Bastogne, on the morning of December 16, 1944, due to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with Allied offensive plans, and poor aerial reconnaissance because to bad weather. The American forces, specifically the US 101st Airborne Division bore the brunt of the attack and incurred their highest casualties of any operation during the war. The town was vital to the Germans, because it would open up a valuable pathway further north for German expansion. The siege had to be stopped, and the 101st Airborne Division needed help to do it.

The capture of Bastogne was the ultimate goal of the Battle of the Bulge…the German offensive through the Ardennes forest. Bastogne provided a road junction in rough terrain where few roads existed. The Belgian town was defended by the US 101st Airborne Division, which had to be reinforced by troops who straggled in from other battlefields. Food, medical supplies, and other resources eroded as bad weather and relentless German assaults threatened the Americans’ ability to hold out. Nevertheless, Brigadier General Anthony C MacAuliffe met a German surrender demand with a typewritten response of a single word, “Nuts.”

This was as bad as it gets, and they needed a hero. Enter “Old Blood and Guts” Patton. General George S Patton Jr was a “street fighter” of a general. He knew what it took to win, and he refused to lose. He was the kind of leader any army, and indeed any government needed. Patton made the decision, the only possible decision he could make. The plan was a “complex and quick-witted strategy wherein he literally wheeled his 3rd Army a sharp 90° turn in a counterthrust movement.” It sounds like a simple plan, but there is no more risk-laden battlefield maneuver than a 90° turn and then a move across and perpendicular to their own lines of communication. The possibilities of mistakes being make were endless. Still, Patton told his men that lives depended on them, and they needed to be in Bastogne…100 miles away, in five days. Not only that, but the march would be over a mountain pass in frigid temperatures. It seemed an impossible

task, but two days later, Patton broke through the German lines and entered Bastogne, relieving the valiant defenders and ultimately pushing the Germans east across the Rhine. I think that if this mission had been asked of any other general, the results might not have been so great. There are generals in war who may annoy everyone around them, but when it comes to doing what is best for the people in trouble, you don’t want anyone else to do the job.

task, but two days later, Patton broke through the German lines and entered Bastogne, relieving the valiant defenders and ultimately pushing the Germans east across the Rhine. I think that if this mission had been asked of any other general, the results might not have been so great. There are generals in war who may annoy everyone around them, but when it comes to doing what is best for the people in trouble, you don’t want anyone else to do the job.

Many people know about the Christmas truce of 1914, when in World War I, thousands of British, French, and German troops, exhausted from fighting took the night of Christmas Eve to stop fighting, leave their trenches, and meet the enemy forces in what was known as “No Man’s Land” to exchange gifts, food, and stories. For the soldiers, it was a moral boost, but the Generals disagreed, and determined to prevent further fraternization in the future, saw to it that such activities would be severely punished, thereby ending future Christmas truces for the rest of that war, or the following war. I suppose the Christmas “truce” would have been better called a “cease fire” since they weren’t supposed to fraternize.

Many people know about the Christmas truce of 1914, when in World War I, thousands of British, French, and German troops, exhausted from fighting took the night of Christmas Eve to stop fighting, leave their trenches, and meet the enemy forces in what was known as “No Man’s Land” to exchange gifts, food, and stories. For the soldiers, it was a moral boost, but the Generals disagreed, and determined to prevent further fraternization in the future, saw to it that such activities would be severely punished, thereby ending future Christmas truces for the rest of that war, or the following war. I suppose the Christmas “truce” would have been better called a “cease fire” since they weren’t supposed to fraternize.

In World War II, of course, there was no such truce called, and the fighting continued without taking notice of the holiday. Nevertheless, in 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, the generals lost just a little bit of their control over the people, when in defiance of the orders, a small group of unlikely guests made their way to a little cabin in the Hurtgen Forest, for a little Christmas Truce of their own. They could have been in so much trouble had they been found out by superior officers, but at the time it just didn’t seem to matter, or maybe it was their host, one Elisabeth Vincken, who along with her 12 year old son stood up to the soldiers, and held off the battle for a few hours. After their home in Aachen was completely destroyed, Elisabeth and her son, Fritz were sent to their cabin, about four miles from Monschau in the Hurtgen Forest near the Belgian border. Her husband visited them as often as he could, but he needed to work. On that Christmas, Elisabeth and Fritz, had been hoping her husband would arrive to spend Christmas with them, but now they knew it was too late. Their Christmas meal would now have to wait for his arrival. Elisabeth and Fritz were alone in the cabin.

Then, the miracle began. Lost in the snow-covered Ardennes Forest, three American soldiers…one badly wounded, wandered around, trying to find the American lines. These poor men had been walking for three days while the sounds of battle echoed in the hills and valleys all around them. They had now idea who was shooting, so they dared not enter the area. Then, on Christmas Eve, they came upon a small cabin in the woods. They cautiously knocked at the door, hoping that they didn’t get shot. Elisabeth blew out the candles and opened the door to find two enemy American soldiers standing at the door and a third lying in the snow behind them. These men might have been soldiers, but were hardly older than boys. The men were armed and  could have simply pushed their way in, but they hadn’t, so she invited them inside and they carried their wounded comrade into the warm cabin. Elisabeth didn’t speak English and they didn’t speak German, but they managed to communicate in broken French. After she heard their story and saw the wounded soldier, Elisabeth gave up the idea of saving the Christmas meal for when her husband could get there. She started preparing a meal for the men. She sent Fritz to get six potatoes and Hermann the rooster…his stay of execution while they waited for her husband was now rescinded. Hermann had been named after Hermann Goering, the Nazi leader, who Elisabeth didn’t care much for. Maybe killing the rooster would make her feel better.

could have simply pushed their way in, but they hadn’t, so she invited them inside and they carried their wounded comrade into the warm cabin. Elisabeth didn’t speak English and they didn’t speak German, but they managed to communicate in broken French. After she heard their story and saw the wounded soldier, Elisabeth gave up the idea of saving the Christmas meal for when her husband could get there. She started preparing a meal for the men. She sent Fritz to get six potatoes and Hermann the rooster…his stay of execution while they waited for her husband was now rescinded. Hermann had been named after Hermann Goering, the Nazi leader, who Elisabeth didn’t care much for. Maybe killing the rooster would make her feel better.

While Hermann roasted and dinner was being prepared, there was another knock on the door. Fritz went to open it, thinking there might be more lost Americans, but instead there were four armed German soldiers. Seeing the German soldiers, and realizing that she could be killed for harboring the enemy, Elisabeth turned white as a ghost. She quickly pushed past Fritz and stepped outside. There was a corporal and three very young soldiers, who wished her a Merry Christmas, but they were lost and hungry. Knowing she had no choice, Elisabeth told them they were welcome to come into the warmth and eat until the food was all gone, but that there were others inside who they would not consider friends. The reaction she expected came when the corporal asked sharply if there were Americans inside and she said there were three who were lost and cold like they were and one was wounded. The corporal stared hard at her. She had to do something, so she said, “Es ist Heiligabend und hier wird nicht geschossen.” In German, that means, “It is the Holy Night and there will be no shooting here.” She insisted they leave their weapons outside. The men couldn’t believe that this woman was standing up to them in such a way. Nevertheless, the men decided to comply and Elisabeth went inside, demanding the same of the Americans. She took their weapons and put them outside next to the Germans’.

Understandably, the fear and tension in the cabin was high as the Germans and Americans eyed each other warily. Nevertheless, the warmth and smell of roast Hermann and potatoes soon eased the tension, and while the men were still wary, the meal was somewhat cordial. The Germans produced a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread. While Elisabeth tended to the cooking, one of the German soldiers, an ex-medical student, examined the wounded American. In English, he explained that the cold had prevented infection, but the man had lost a lot of blood. He needed food and rest. By the time the meal was ready, the atmosphere in the cabin was more relaxed. Two of the Germans were only sixteen, and the corporal was only 23. As Elisabeth said grace, Fritz  noticed tears in the exhausted soldiers’ eyes…both German and American. The moment had somehow touched them all. The unauthorized and very much unplanned “truce” lasted through the rest of that night, and into the morning. The German corporal looked at the map the Americans had, and pointed out the best way for the men to get back to their lines. He also gave them a compass. The Americans asked if they should instead go to Monschau, but the corporal shook his head and said that the Germans had taken Monschau. Elisabeth returned all their weapons and the enemies shook hands and left the cabin, in opposite directions. Soon they were all out of sight, and the truce was over.

noticed tears in the exhausted soldiers’ eyes…both German and American. The moment had somehow touched them all. The unauthorized and very much unplanned “truce” lasted through the rest of that night, and into the morning. The German corporal looked at the map the Americans had, and pointed out the best way for the men to get back to their lines. He also gave them a compass. The Americans asked if they should instead go to Monschau, but the corporal shook his head and said that the Germans had taken Monschau. Elisabeth returned all their weapons and the enemies shook hands and left the cabin, in opposite directions. Soon they were all out of sight, and the truce was over.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

There were heroes on that day, however. The people who worked to save what lives they could, and put out the fires caused by the attack. And there were two heroes I had never heard about. I’m not sure why I hadn’t, but the fact remains that I hadn’t. Kenneth Taylor and George Welch were pilots stationed at Pearl Harbor on that fateful day. Taylor was a second lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps’ 47th Pursuit Squadron. He received his first posting to Wheeler Army Airfield in Honolulu, Hawaii in April 1941. His commanding officer, General Gordon Austin, chose Taylor and another pilot, George Welch, as his flight commanders shortly after they arrived in Hawaii. A week before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 47th Pursuit Squadron was temporarily moved to the auxiliary airstrip at Haleiwa Field, located some 11 miles from Wheeler, for gunnery practice…a move that made their response to the attack possible.

Saturday, December 6, 1941, found Taylor and Welch spending the evening at a dance held at the officers’ club at Wheeler Field. After the dance, the two pilots joined an all-night poker game. After that, the account of the story gets a little fuzzy. Some said that the two pilots had finally gone to sleep, and were awoken only around 7:51am, when Japanese fighter planes and dive bombers attacked Wheeler, but others said that the poker game was just wrapping up, and they were contemplating a morning swim when the attack began. Whatever the case may be, Taylor and Welch were stunned to hear low-flying planes, explosions, and machine-gun fire above them. Information was scarce in all the chaos, but they learned that two-thirds of the planes at the main bases of Hickham and Wheeler Fields had been destroyed or damaged so badly that they were unable to fly. The two men rush to Haleiwa Field to get their planes. They had no orders, but Taylor called Haleiwa and  commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

When they reached the field, Welch and Taylor jumped into their P-40s, which by that time had been fueled but not fully armed. That didn’t stop them. They took off and immediately attracted Japanese fire. Welch and Taylor were facing off virtually alone against some 200 to 300 enemy aircraft. When they ran out of ammunition, they returned to Wheeler to reload. The senior officers ordered the pilots to stay on the ground, but then

the second wave of Japanese raiders flew in, scattering the crowd. Taylor and Welch took off again, in the midst of a swarm of enemy planes. Though Welch’s machine guns were disconnected, he fired his .30-caliber guns, destroying two Japanese planes on the first attack run. On the second, with his plane heavily damaged by gunfire, he shot down two more enemy aircraft. A bullet pierced the canopy of Taylor’s plane, hitting his arm and sending shrapnel into his leg, but he managed to shoot down at least two Japanese planes, and perhaps more. In the end, Taylor was officially credited with two kills, and Welch with four.

Welch and Taylor were among only five Air Force pilots who managed to get their planes off the ground and engage the Japanese that morning. The total loss in aircraft at Pearl Harbor were estimated at 188 planes destroyed and 159 damaged. The Japanese lost just 29 planes. Both men were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross medals, becoming the first to be awarded that distinction in World War II. Welch was nominated for the Medal of Honor, the military’s highest award, but was reportedly denied because his superiors maintained he had taken off without proper authorization. For his injuries, Taylor received the Purple Heart.

After Pearl Harbor, George Welch flew nearly 350 missions in the Pacific Theater during World War II, shooting down 12 more planes and winning many other decorations. After he contracted malaria in 1943, his wartime career came to an end. While in the hospital in Sydney, Australia, he met his wife. After the war, Welch became a test pilot for North American Aviation. There are some claims that he became the first pilot to break the Mach-1 barrier with an unauthorized flight over the California desert in 1947, several weeks before Chuck Yeager’s famous flight. Unfortunately, Welch was killed in 1954 while ejecting from his disintegrating F-100 Super Sabre fighter jet during a test flight.

After Pearl Harbor, Ken Taylor was transferred to the South Pacific, where he flew out of Guadalcanal and was credited with downing another Japanese aircraft. Unfortunately, his combat career was cut short after someone fell on top of him in a trench during an air raid on the base, breaking his leg. He became a commander in the Alaska Air National Guard and retired as a brigadier general after 27 years of active duty. Taylor was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion of Merit, the Air Medal, and a number of other decorations. In his post military career, he worked as an insurance underwriter. Taylor died in Tucson, Arizona in 2006, at the age of 86.

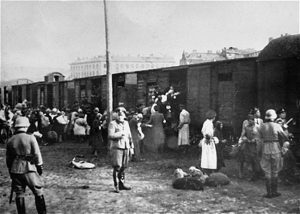

When Hitler decided that the time in his “final solution” had come to transport the Jews, Gypsies, and other “undesirables” to the death camps, he chose to transport them in cattle cars on a train. Hitler had so little compassion for human life, that when the people were loaded into the cattle cars, they were packed in tightly with as many 80 people to a car. They couldn’t sit down. The air was stifling. The trains didn’t stop for bathroom breaks or food. The people had to stand there hour after hour, for up to four very long days. Hitler and his men didn’t care, they didn’t even consider the people to be human, and to make matters worse, they thought it a good thing if the people just died en route, because it would save them the hassle, ammunition, and poison needed to kill them later.

When Hitler decided that the time in his “final solution” had come to transport the Jews, Gypsies, and other “undesirables” to the death camps, he chose to transport them in cattle cars on a train. Hitler had so little compassion for human life, that when the people were loaded into the cattle cars, they were packed in tightly with as many 80 people to a car. They couldn’t sit down. The air was stifling. The trains didn’t stop for bathroom breaks or food. The people had to stand there hour after hour, for up to four very long days. Hitler and his men didn’t care, they didn’t even consider the people to be human, and to make matters worse, they thought it a good thing if the people just died en route, because it would save them the hassle, ammunition, and poison needed to kill them later.

I suppose that for Hitler and the Nazis, the plan was one of simple logistics of transporting millions of people to southern Poland. Some of the people came from as far away as the Netherlands, France, Italy, and Greece. Transportation was done occasionally in passenger trains, in which wealthy Jews were encouraged to bring as much of their wealth with them as possible. Oh course, the Jews thought they would be able to keep their belongings, but in reality, this was railway robbery, because their wealth was soon to be transferred to the Nazis. Where they were going, they would not need their property.

The transports of the Jews to Auschwitz went of daily, on schedule. They leave from the ghetto embarkation depots, on schedule. The process was very methodical…almost mechanical, or robotic. Those in charge had no compassion for the people being herded into the cattle cars. The conductors signaled, “All aboard.” The brakemen waved lanterns. Anyone who resisted was shot by German and Hungarian guards. Guards used clubs and bayonets to herd a last group of mothers into the compartments. Finally, the engineer opens the throttle, and right on schedule, the train is off for Auschwitz.

Eighty Jews in every compartment was the average, but Eichmann boasted that the Germans could do better where there were more children. With the children in the groups, they could jam 120 into each train room. The Jews had to stand all the way to Auschwitz…with their hands raised in the air…because that made room for the maximum number of passengers. Each compartment had two buckets…one containing water, and the other to use as a toilet, to be shoved by foot, if possible, from user to user, not that anyone could use their hands to facilitate waste elimination. Many just had to relieve themselves where they stood, through their clothing. The water buckets made no sense either, because one water bucket for over eighty people for four days, would never be enough, if they could figure out a way to get the water from the bucket to their mouths. Still, no one could say the Nazis were cruel…after all, the buckets were there, right? In the four days that it took to get to Auschwitz, many, if not all of the prisoners were dead, standing up, because in the tight quarters, the dead

could not even fall. Those who survived were to face an worse fate than dying on the train. They faced slavery, forced experimentation, and finally the gas chambers. Children were separated from parents, men from women, and the elderly simply sent straight to the gas chambers. People were mutilated, poisoned, beaten, forced to stand outside naked in the bitter cold of winter or in the heat of summer, crammed into quarters with no heat or blankets, and starved to death on a mere 700 calories or less a day. Death was the best option.

could not even fall. Those who survived were to face an worse fate than dying on the train. They faced slavery, forced experimentation, and finally the gas chambers. Children were separated from parents, men from women, and the elderly simply sent straight to the gas chambers. People were mutilated, poisoned, beaten, forced to stand outside naked in the bitter cold of winter or in the heat of summer, crammed into quarters with no heat or blankets, and starved to death on a mere 700 calories or less a day. Death was the best option.

Most airplanes in the 1940s were of a similar design…the kind that were a simple wing design. There was, however, a futuristic flying machine that made it’s debut on October 21, 1947. The Northrup YB-49 Flying Wing was a prototype jet-powered heavy bomber developed by Northrop Corporation shortly after World War II for service with the United States Air Force. The YB-49 featured a futuristic flying wing design and was a turbojet-powered version of the earlier, piston-engined Northrop XB-35 and YB-35. The test flight of the Northrop YB-49 took place at Northrop Field, Hawthorne, California. It was piloted by Chief Test Pilot Max R Stanley. That first flight seemed to be going well, but it faced stability problems during simulated bomb runs and political problems doomed the flying wing.

Most airplanes in the 1940s were of a similar design…the kind that were a simple wing design. There was, however, a futuristic flying machine that made it’s debut on October 21, 1947. The Northrup YB-49 Flying Wing was a prototype jet-powered heavy bomber developed by Northrop Corporation shortly after World War II for service with the United States Air Force. The YB-49 featured a futuristic flying wing design and was a turbojet-powered version of the earlier, piston-engined Northrop XB-35 and YB-35. The test flight of the Northrop YB-49 took place at Northrop Field, Hawthorne, California. It was piloted by Chief Test Pilot Max R Stanley. That first flight seemed to be going well, but it faced stability problems during simulated bomb runs and political problems doomed the flying wing.

The unusual configuration, for an aircraft of that time, had no fuselage or tail control surfaces. The crew compartment, engines, fuel, landing gear, and armament were contained within the wing. Air intakes for the turbojet engines were placed in the leading edge and the exhaust nozzles were at the trailing edge. Four small vertical fins for improved yaw stability were also at the trailing edge. While the design might have had many stabilizing characteristics, it was still basically a set of wings, connected together, with a small crew  compartment in the middle. I suppose it looked like an early version of the F-117 Nighthawk stealth airplane, but with much bigger wings and a much smaller crew cabin.

compartment in the middle. I suppose it looked like an early version of the F-117 Nighthawk stealth airplane, but with much bigger wings and a much smaller crew cabin.

The YB-49 was powered by eight General Electric, Allison Engine Company, J35-A-5 engines. A variant of that engine was used in the North American Aviation XP-86, replacing its original Chevrolet-built J35-C-3. The engines were later upgraded to J35-A-15s. The J35 was a single-spool, axial-flow turbojet engine with an 11-stage compressor and single-stage turbine. It shocks me that there was such a thing as a turbojet engine back then, but apparently there was. During the testing of the YB-49, it reached a maximum speed of 428 knots (493 miles per hour) at 20,800 feet. It had a cruising speed of 365 knots (429 miles per hour). The airplane had a service ceiling of 49,700 feet. The YB-49 had a maximum fuel capacity of 14,542 gallons of JP-1 jet fuel. Its combat radius was 1,403 nautical miles. The maximum bomb load of the YB-49 was 16,000 pounds, though the actual number of bombs was limited by the volume of the bomb bay and the capacity of each bomb type. While the YB-35 Flying Wing was planned for multiple machine gun turrets, but none were attached.

In the second test flight, the unstable YB-49 crashed on Jan. 13, 1948. After the crash, the testing continued with both aircraft until the second YB-49 crashed on June 5, 1948. They tried to make the plane work, but it just didn’t seem to be in the cards. The crew of the crashed YB-49 included Major Daniel H Forbes Jr, pilot; Captain Glen W Edwards, copilot; Lieutenant Edward L Swindell, flight engineer; Clare E Lesser and C C La Fountain. Later, The two pilots were honored with the naming of two Air Force installations. Edwards Air Force Base, California, was named in honor of Captain Edwards, and Forbes Air Force Base, Kansas, was named in honor of Major Forbes.

In the second test flight, the unstable YB-49 crashed on Jan. 13, 1948. After the crash, the testing continued with both aircraft until the second YB-49 crashed on June 5, 1948. They tried to make the plane work, but it just didn’t seem to be in the cards. The crew of the crashed YB-49 included Major Daniel H Forbes Jr, pilot; Captain Glen W Edwards, copilot; Lieutenant Edward L Swindell, flight engineer; Clare E Lesser and C C La Fountain. Later, The two pilots were honored with the naming of two Air Force installations. Edwards Air Force Base, California, was named in honor of Captain Edwards, and Forbes Air Force Base, Kansas, was named in honor of Major Forbes.

Yang Kyoungjong was a Korean man with an incredible story. In 1938, when he was 18 years old, Kyoungjong was in Manchuria when he was forced into the Kwantung Army of the Imperial Japanese Army to fight against the Soviet Union. It was the outbreak of World War II, and I suppose the Japanese decided they would be better off to make him soldier than to let him languish in a prisoner of war camp. So, fight he did. Korea was ruled by Japan at that time, and Kyoungjong really had no choice to to follow orders.

Yang Kyoungjong was a Korean man with an incredible story. In 1938, when he was 18 years old, Kyoungjong was in Manchuria when he was forced into the Kwantung Army of the Imperial Japanese Army to fight against the Soviet Union. It was the outbreak of World War II, and I suppose the Japanese decided they would be better off to make him soldier than to let him languish in a prisoner of war camp. So, fight he did. Korea was ruled by Japan at that time, and Kyoungjong really had no choice to to follow orders.

During the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, things weren’t going well for the Japanese army, and Kyoungjong was again captured…this time by the Soviet Red Army. He was sent to a Gulag labor camp. While he was there, and with Soviet manpower shortages being what they were, Kyoungjong was presses into service in the Soviet army in 1942. He, along with thousands of other prisoners, were told to fight with the Red Army against Nazi Germany. He was sent to the Eastern Front of Europe.

Somehow, Kyoungjong managed to always be in the wrong place at the wrong time. In 1943, he was once again captured, this time by the Wehrmacht soldiers in eastern Ukraine during the Third Battle of Kharkov. He  was pressed into service again, and told that he had joined the “Eastern Battalions” to fight for Germany. Kyoungjong was sent to Occupied France to serve in a battalion of former Soviet prisoners of war on the Cotentin peninsula in Normandy, close to Utah Beach. I’m sure he wondered which army he was really a part of.

was pressed into service again, and told that he had joined the “Eastern Battalions” to fight for Germany. Kyoungjong was sent to Occupied France to serve in a battalion of former Soviet prisoners of war on the Cotentin peninsula in Normandy, close to Utah Beach. I’m sure he wondered which army he was really a part of.

During the D-Day landings in northern France by the Allied forces, Kyoungjong was captured by paratroopers of the United States Army in June 1944. The American Army thought he was a Japanese soldier in German uniform at first. At the time, Lieutenant Robert Brewer of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, reported that his regiment had “captured four Asians in German uniform after the Utah Beach landings, and that initially no one was able to communicate with them.” The good news for Kyoungjong was that he was not going to again be expected to fight with a different army. He was first sent to a prison camp in Britain and later transferred to a camp in the United States.

During World War II, when Japan was the enemy, and the United States just happened to have a Japanese population of between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry. The government decided to place these people in internment camps, mainly because they were not sure of their loyalty. Sixty-two percent of the internees were United States citizens, but somehow that didn’t matter. The American people and the government were afraid of them. Maybe it made no sense, but there it was.

During World War II, when Japan was the enemy, and the United States just happened to have a Japanese population of between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry. The government decided to place these people in internment camps, mainly because they were not sure of their loyalty. Sixty-two percent of the internees were United States citizens, but somehow that didn’t matter. The American people and the government were afraid of them. Maybe it made no sense, but there it was.

While their families were interned in camps at home, a group of Japanese-Americans, were serving their country as members of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Infantry Regiment. The 100th Infantry Battalion was composed mainly of Nisei…the American born children of Japanese immigrants. They were fighting for the allies on the Western Front of World War II. While the American people did not trust the Japanese immigrants or their children, this unit, out of all units of comparable size and length of service, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) is, to this day, the most decorated unit in American military history.

Most of the men in the 100th Infantry Battalion were former Nisei members from the Hawaii National Guard. These brave men fought to capture the fortress of Monte Cassino in Italy. It was in this battle that the 100th Infantry Battalion first earned the nickname “Purple Heart Battalion.” The battle to capture the fortress of Monte Cassino was an important stage in the offensive to liberate Rome from Axis leaders. The 100th Infantry Battalion later became incorporated into the 442nd RCT, which drew most of its forces from mainland Nisei volunteers, after the regiment arrived in Europe.

During the war, one battle stood out…at least in my mind. It was one that proves without a doubt, the extreme loyalty and courage of this unit. Among their other military accomplishments, the 442nd RCT was instrumental in the rescue of the “Lost Battalion.” In a daring last-ditch effort, members of the 442nd RCT were ordered to rescue a battalion of Texans surrounded by German troops in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France. Although the Nisei knew that they would suffer heavy casualties, many saw the mission as a chance to prove their loyalty. The regiment was also critical in the breach of the Gothic Line. Embedded within the Apennine

Mountains, it was Germany’s last major line of defense in the Italian Campaign. Later, members of the regiment were present at the liberation of the infamous Dachau concentration camp in Germany. For some of the soldiers, the experience was a bittersweet one; although they were able to emancipate the prisoners of the camp, they could not help but remember their detained families at home.

Mountains, it was Germany’s last major line of defense in the Italian Campaign. Later, members of the regiment were present at the liberation of the infamous Dachau concentration camp in Germany. For some of the soldiers, the experience was a bittersweet one; although they were able to emancipate the prisoners of the camp, they could not help but remember their detained families at home.

I am always amazed at the lengths nations will go to try to have a better weapon with which to war against their enemies. Some of the weapons were horrifically great successes, while others only succeeded in being amusingly unsuccessful. It seems that the Germans were famous for trying to come up with unusual ideas for weaponry. In fact, World War II seemed to be full of bizarre weapons.

I am always amazed at the lengths nations will go to try to have a better weapon with which to war against their enemies. Some of the weapons were horrifically great successes, while others only succeeded in being amusingly unsuccessful. It seems that the Germans were famous for trying to come up with unusual ideas for weaponry. In fact, World War II seemed to be full of bizarre weapons.

Wars always present opportunities for technological development, but Germany seemed to be particularly motivated to pour considerable resources into weapons projects. The level of success, varied with the weapons. That is not unusual, as weapons go, but I think that when you look some of the bizarre weapon designs that Germany came up with really seemed like a recipe for calamity to me. The weapons they came up with had varying degrees of success. The Germans developed the V-2 rocket, which both rained destruction on the United Kingdom and jumpstarted the space race. On the other hand, they also tried to build a “sun gun,” an orbital heat ray that was supposed to use reflected sunlight to torch cities.

The V-3 cannon project falls in the middle of the spectrum of weaponry. In the end, it never threatened the Allied powers, but if it had been given more production time, it very well could have. The V-3 was an extremely long artillery piece, over 430 feet in length. It was designed to fire projectiles up to a distance of 100 miles away. The V-3 cannon was built to bombard British cities from mainland Europe, bypassing the need for planes or the V-2. These enormous guns had been in development since World War I, on both sides of the conflict, but to this point these weapons hadn’t been deployed in combat. The problem was that the size of an explosion needed to propel a projectile over such a distance was so large that it would quickly destroy any gun barrel. They just couldn’t get that part fixed.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Germans rediscovered the plans for the V-3 and began to research them  again. In 1943, Hitler restarted the V-3 project under his Armaments and War Procurement Minister, Albert Speer. The first goal was to solve the explosion problem. It was decided that the V-3 would use several small explosions that would propel the projectile along the barrel. Even with that change, the barrel was so large and unwieldy that it couldn’t be aimed. It had to be built already aiming at the intended target, and the target had to be the size of a city. That is a tall order.

again. In 1943, Hitler restarted the V-3 project under his Armaments and War Procurement Minister, Albert Speer. The first goal was to solve the explosion problem. It was decided that the V-3 would use several small explosions that would propel the projectile along the barrel. Even with that change, the barrel was so large and unwieldy that it couldn’t be aimed. It had to be built already aiming at the intended target, and the target had to be the size of a city. That is a tall order.

The Germans made plans to build 50 V-3 cannons on the French coastline, but RAF bombings delayed the project. When the Allies retook France in 1944, the V-3 project was again abandoned. The Allies didn’t learn of the V-3 project until after World War II had ended. Winston Churchill said that “if the guns had been completed, they could have devastated England more than any other German weapon.” Thankfully the Allies retook France in time to avoid such a disaster.