United States

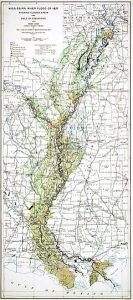

The Mississippi River is a is the widest river in the United States. It’s mere size and the amount of water in it, makes one expect that at some point, it is going to flood. In fact, it has flooded many times over the years, but none was anything like the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. It was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States. In all, 27,000 square miles of land were inundated with water up to a 30 feet depth. In all, 630,000 people were affected by the flood. About 94% of them lived in the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, most in the Mississippi Delta. At least 15 inches of rain fell in 18 hours causing the Mississippi River to brake out of its levee system at 145 locations. Ten states were affected…Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Arkansas was the worst affected with 14% of the state flooded.

The Mississippi River is a is the widest river in the United States. It’s mere size and the amount of water in it, makes one expect that at some point, it is going to flood. In fact, it has flooded many times over the years, but none was anything like the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. It was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States. In all, 27,000 square miles of land were inundated with water up to a 30 feet depth. In all, 630,000 people were affected by the flood. About 94% of them lived in the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, most in the Mississippi Delta. At least 15 inches of rain fell in 18 hours causing the Mississippi River to brake out of its levee system at 145 locations. Ten states were affected…Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Arkansas was the worst affected with 14% of the state flooded.

It was Good Friday, April 15, 1927, the disaster began when 15 inches of rain fell in New Orleans in 18 hours. More than 4 feet of water covered parts of the city. A group of influential bankers in town met to discuss how to guarantee the safety of the city, as they had already learned of the massive scale of flooding upriver. A few weeks after, they arranged to set off about 30 tons of dynamite on the levee at Caernarvon, in an effort to flood a less populated area and save the cities that would have been severely damaged. I’m not sure how much this effort helped, and in the end, about 500 people lost their lives anyway. It wouldn’t be the last Mississippi River flood, but it would be the worst.

As a result of the flooding, many of the misplaced people joined the Great Migration from the south to northern and midwestern industrial cities rather than return to rural agricultural labor. I would think that the idea of such a massive amount of cleanup would be more than many people could take. This massive population movement increased from World War II until 1970. Of course, this volume of population movement would not be good for the states who were losing people. To try to prevent future floods, the federal government built the world’s

longest system of levees and floodways. By August 1927, when the flood subsided, hundreds of thousands of people had been made homeless and displaced; properties, livestock and crops were destroyed. Flooding on the Mississippi is not an unusual event, and no matter how many precautions we take, there will still be losses when the river overflows its banks.

longest system of levees and floodways. By August 1927, when the flood subsided, hundreds of thousands of people had been made homeless and displaced; properties, livestock and crops were destroyed. Flooding on the Mississippi is not an unusual event, and no matter how many precautions we take, there will still be losses when the river overflows its banks.

In a time of global pandemic, many people are thinking about the Coronavirus, and the impact it is having on all our lives. Of course, there have been a number of pandemics in years past, such as the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918, that killed 50,000,000 worldwide. The pandemic was active from January 1918 to December 1920. So little was known then about how to protect ourselves from these things, or even what a virus was. We learned from that pandemic and others as the years went on.

In a time of global pandemic, many people are thinking about the Coronavirus, and the impact it is having on all our lives. Of course, there have been a number of pandemics in years past, such as the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918, that killed 50,000,000 worldwide. The pandemic was active from January 1918 to December 1920. So little was known then about how to protect ourselves from these things, or even what a virus was. We learned from that pandemic and others as the years went on.

One such epidemic was the Polio Epidemic in the United States, the 1952 epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation’s history. It is credited with heightening parents’ fears of the disease and focusing public awareness on the need for a vaccine. Of the 57,628 cases reported that year 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis. Finally, on March 26, 1953, American medical researcher Dr Jonas Salk announced on a national radio show that he has successfully tested a vaccine against poliomyelitis, which is the virus that causes the crippling disease of polio. Dr Salk was celebrated as the great doctor-benefactor of his time, for promising eventually to eradicate the disease, which is known as “infant paralysis” because it mainly affects children.

Polio attacks the nervous system and can cause varying degrees of paralysis. The disease affected humanity throughout recorded history, and since the virus is easily transmitted, epidemics were commonplace in the first decades of the 20th century. The summer of 1894 brought the United States first major polio epidemic, beginning in Vermont. By the 20th century thousands were affected every year. In the first decades of the 20th century, treatments were limited to quarantines and the infamous “iron lung,” a metal coffin-like contraption that aided respiration. Although children, and especially infants, were among the worst affected, adults were  also commonly afflicted, including future president Franklin D Roosevelt, who in 1921 was stricken with polio at the age of 39 and was left partially paralyzed. Roosevelt later transformed his estate in Warm Springs, Georgia, into a recovery retreat for polio victims and was instrumental in raising funds for polio-related research and the treatment of polio patients.

also commonly afflicted, including future president Franklin D Roosevelt, who in 1921 was stricken with polio at the age of 39 and was left partially paralyzed. Roosevelt later transformed his estate in Warm Springs, Georgia, into a recovery retreat for polio victims and was instrumental in raising funds for polio-related research and the treatment of polio patients.

Salk’s procedure, first attempted unsuccessfully by American Maurice Brodie in the 1930s, was to kill several strains of the virus and then inject the benign viruses into a healthy person’s bloodstream. The person’s immune system would then create antibodies designed to resist future exposure to poliomyelitis. Salk conducted the first human trials on former polio patients, on himself, and his family. By 1953, he was ready to announce his findings. The announcement was made on March 25th, on the CBS national radio network, and two days later in an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Dr Salk became an immediate celebrity.

Clinical trials using the Salk vaccine and a placebo began in 1954 on nearly two million American schoolchildren. It was announced that the vaccine was effective and safe in April 1955, and a nationwide inoculation campaign began. Unfortunately a defective vaccine manufactured at Cutter Laboratories of Berkeley, California, had tragic results in the Western and mid-Western United States, when more than 200,000 people were injected with a defective vaccine, and thousands of polio cases were reported, 200 children were left paralyzed and 10 died.

The ensuing panic delayed production of the vaccine. Still, new polio cases dropped to under 6,000 in 1957, the  first year after the vaccine was widely available. So, other than the defective vaccine, maybe it was working. Scientists continued to improve the product, and in 1962, an oral vaccine developed by Polish-American researcher Albert Sabin became available, greatly facilitating distribution of the polio vaccine. These days, polio has been all but wiped out, and there are just a handful of polio cases in the United States every year. Most of these are “imported” by Americans from developing nations where polio is still a problem. Jonas Salk was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977, among other honors. He died in La Jolla, California, in 1995.

first year after the vaccine was widely available. So, other than the defective vaccine, maybe it was working. Scientists continued to improve the product, and in 1962, an oral vaccine developed by Polish-American researcher Albert Sabin became available, greatly facilitating distribution of the polio vaccine. These days, polio has been all but wiped out, and there are just a handful of polio cases in the United States every year. Most of these are “imported” by Americans from developing nations where polio is still a problem. Jonas Salk was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977, among other honors. He died in La Jolla, California, in 1995.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the people of the United States were justifiably nervous about the Japanese American citizens. Many of these people had family in Japan, and their loyalty was in question. No one felt safe, so on February 19, 1942, just 10 weeks later, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of any or all people from military areas “as deemed necessary or desirable.”

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the people of the United States were justifiably nervous about the Japanese American citizens. Many of these people had family in Japan, and their loyalty was in question. No one felt safe, so on February 19, 1942, just 10 weeks later, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of any or all people from military areas “as deemed necessary or desirable.”

The feeling of panic that had been simmering since the attack wasn’t going away when it came to the Japanese, or the Japanese Americans, so the military defined the entire West Coast, home to the majority of Americans of Japanese ancestry or citizenship, as a military area. What began as a plan to protect the military areas, quickly escalated, and by June, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to remote internment camps built by the United States military in scattered locations around the  country, where they would remain for the next two and a half years. Many of these Japanese Americans endured extremely difficult living conditions and poor treatment by their military guards. It wasn’t what we would expect of our own military, but it was a tense time. It almost seemed like “guilt by association” or in this case, by race. They were Japanese, and that made people wary of them…and no one was in the mood to listen to their side.

country, where they would remain for the next two and a half years. Many of these Japanese Americans endured extremely difficult living conditions and poor treatment by their military guards. It wasn’t what we would expect of our own military, but it was a tense time. It almost seemed like “guilt by association” or in this case, by race. They were Japanese, and that made people wary of them…and no one was in the mood to listen to their side.

The internment of these loyal Japanese Americans was, at the very least, unfair, and at worst, just short of criminal. It was only short of criminal because it was approved by the President of the United States. Finally, after two and a half years, United States Major General Henry C Pratt issued Public Proclamation No. 21, declaring that, effective January 2, 1945, Japanese American “evacuees” from the West Coast could return to their homes. The nightmare was over. Of  course, being over doesn’t mean that everything went immediately back to the way it was before. These people had to find new jobs and homes, because their jobs, and possibly their homes, were no longer there for them to return to.

course, being over doesn’t mean that everything went immediately back to the way it was before. These people had to find new jobs and homes, because their jobs, and possibly their homes, were no longer there for them to return to.

During the course of World War II, ten Americans were convicted of spying for Japan, but not one of them was of Japanese ancestry, which is disgusting…not that no Japanese Americans were part of that, but that any American would betray their country in this way. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill to recompense each surviving internee with a tax-free check for $20,000 and an apology from the United States government.

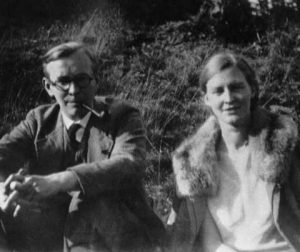

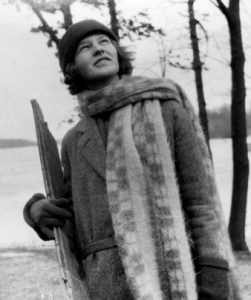

It was a big move for a Milwaukee, Wisconsin girl, but in the end, it would be her undoing. Mildred Fish was born in Milwaukee in 1902, and upon her high school graduation, she studied and then taught English at UW-Madison. It was there that she met Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. They soon fell in love, and were married in 1926. Because she was a progressive woman and proud of her name, Mildred chose to hyphenate her name, and became known as Mildred Fish-Harnack.

It was a big move for a Milwaukee, Wisconsin girl, but in the end, it would be her undoing. Mildred Fish was born in Milwaukee in 1902, and upon her high school graduation, she studied and then taught English at UW-Madison. It was there that she met Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. They soon fell in love, and were married in 1926. Because she was a progressive woman and proud of her name, Mildred chose to hyphenate her name, and became known as Mildred Fish-Harnack.

A few years later, she and Arvid both moved to Germany, where she taught and also worked on her doctorate while he worked for the German government. It was during those years that Fish-Harnack became interested in the Soviet Union, where women could choose where to work and also had other rights that women in the United States did not have…a situation which would very soon sound absurd. Nevertheless, at that time, it was so. Throughout the 1930s, Mildred and Arvid, who became increasingly  alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power, began to communicate with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe. As the Hitler and the Nazi regime began to come into power, Fish-Harnack and her husband joined a small resistance group, which the Nazi secret police…the Gestapo…would later call the Red Orchestra. This resistance group smuggled important secrets about the Nazis to the United States and Soviet governments and helped Jews escape from Germany. When war was declared in 1941, she did not leave with other American expatriates.

alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power, began to communicate with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe. As the Hitler and the Nazi regime began to come into power, Fish-Harnack and her husband joined a small resistance group, which the Nazi secret police…the Gestapo…would later call the Red Orchestra. This resistance group smuggled important secrets about the Nazis to the United States and Soviet governments and helped Jews escape from Germany. When war was declared in 1941, she did not leave with other American expatriates.

Of course, their activities were espionage and would eventually cost them their lives. For his part, her husband,  Arvid was hanged in December 1942. Mildred was given a six year sentence, but Hitler refused to endorse her punishment and she was retried and condemned on February 16, 1943. She was beheaded by guillotine. Because of her connection to possible communist sympathies and post-war McCarthyism, her story is virtually unknown in the United States. She was the only American woman who was ever put to death on the direct order of Adolf Hitler for her involvement in the resistance movement. Her last words were, “And I have loved Germany so much.” In the Cold War years after World War II, Fish-Harnack’s name and legacy were not honored in the United States, because she and her husband were believed to have been connected with Communism. For a time they were hated by both of their home countries. Once the truth came out in 1986, that changed and Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was established in Wisconsin. It takes place every year on her birthday, September 16th.

Arvid was hanged in December 1942. Mildred was given a six year sentence, but Hitler refused to endorse her punishment and she was retried and condemned on February 16, 1943. She was beheaded by guillotine. Because of her connection to possible communist sympathies and post-war McCarthyism, her story is virtually unknown in the United States. She was the only American woman who was ever put to death on the direct order of Adolf Hitler for her involvement in the resistance movement. Her last words were, “And I have loved Germany so much.” In the Cold War years after World War II, Fish-Harnack’s name and legacy were not honored in the United States, because she and her husband were believed to have been connected with Communism. For a time they were hated by both of their home countries. Once the truth came out in 1986, that changed and Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was established in Wisconsin. It takes place every year on her birthday, September 16th.

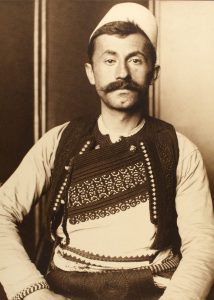

The United States has long been known as “The Melting Pot,” in reference to the immigration of many of its citizens. The United States was not a country that began with all of its people in place. I suppose no nation was really. There is, however, a legal way to immigrate, and an illegal way to sneak into a country. For the purpose of this story, the melting pot refers only to legal immigration. Beginning in 1892, and continuing until 1924, Ellis Island, located in New York Harbor, was the entrance for immigrants entering the United States. Not everyone who entered the United States had to go through Ellis Island, however. First and Second Class passengers were not so required. They were allowed to do all of their immigration paperwork, and inspections onboard the ship that arrived on. The Third Class passengers, however, were required to go through Ellis Island. There, they had medical exams and legal inspections to determine if they were fit for entry into the United States.

The United States has long been known as “The Melting Pot,” in reference to the immigration of many of its citizens. The United States was not a country that began with all of its people in place. I suppose no nation was really. There is, however, a legal way to immigrate, and an illegal way to sneak into a country. For the purpose of this story, the melting pot refers only to legal immigration. Beginning in 1892, and continuing until 1924, Ellis Island, located in New York Harbor, was the entrance for immigrants entering the United States. Not everyone who entered the United States had to go through Ellis Island, however. First and Second Class passengers were not so required. They were allowed to do all of their immigration paperwork, and inspections onboard the ship that arrived on. The Third Class passengers, however, were required to go through Ellis Island. There, they had medical exams and legal inspections to determine if they were fit for entry into the United States.

It is estimated that 12 million immigrants came through Ellis Island in those years. In all, about 2% were denied entrance into the United States. Our nation was quite generous with its legal immigration requests. One

of the main reasons for the opening of Ellis Island was the change in the immigration requests. “Fewer arrivals were coming from northern and western Europe—Germany, Ireland, Britain and the Scandinavian countries—as more and more immigrants poured in from southern and eastern Europe. Among this new generation were Jews escaping from political and economic oppression in czarist Russia and eastern Europe (some 484,000 arrived in 1910 alone) and Italians escaping poverty in their country. There were also Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks and Greeks, along with non-Europeans from Syria, Turkey and Armenia. The reasons they left their homes in the Old World included war, drought, famine and religious persecution, and all had hopes for greater opportunity in the New World.”

of the main reasons for the opening of Ellis Island was the change in the immigration requests. “Fewer arrivals were coming from northern and western Europe—Germany, Ireland, Britain and the Scandinavian countries—as more and more immigrants poured in from southern and eastern Europe. Among this new generation were Jews escaping from political and economic oppression in czarist Russia and eastern Europe (some 484,000 arrived in 1910 alone) and Italians escaping poverty in their country. There were also Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks and Greeks, along with non-Europeans from Syria, Turkey and Armenia. The reasons they left their homes in the Old World included war, drought, famine and religious persecution, and all had hopes for greater opportunity in the New World.”

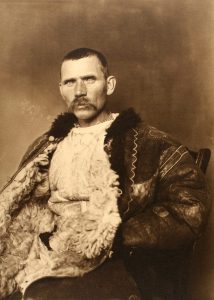

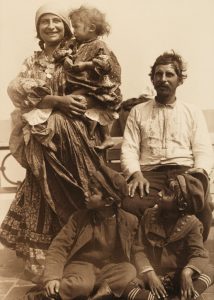

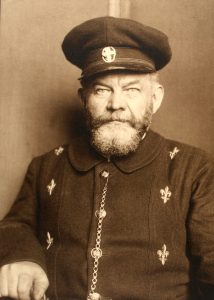

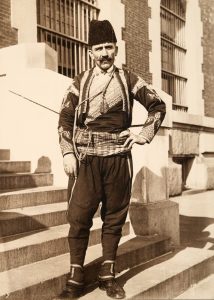

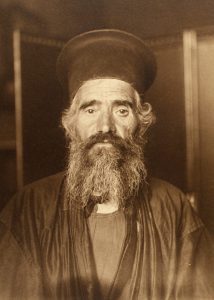

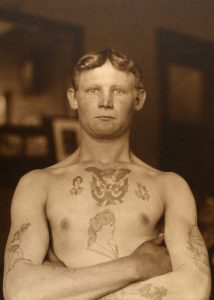

At one point, one of the men working on Ellis Island decided to bring his camera, and document the variety of people coming through. His photos really do show the “melting pot” that the United States was. He photographed a Romanian shepherd, a Serbian gypsy family, Danish captain, a bearded Greek priest, a Turkish bank guard, an Albanian soldier, an Algerian (wearing his finest clothes), and a tattooed German stowaway (who was eventually deported). It gives an inside look at the varied people who came to the United States,

and these were just the third class passengers, seen on Ellis Island.

and these were just the third class passengers, seen on Ellis Island.

Ellis Island was used as an immigration center until 1924, at which time it was used until 1954 as a detention and deportation center for illegal immigrants. Now it is a museum, and a place where people can go to see if their ancestors came through on their way to a better life. The island had a varied past, and played a major role in creating “The Melting Pot” the United States was.

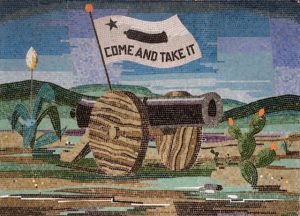

Since the 17th century, Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans called it, had technically been a part of the Spanish empire. However, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas, even as late as the 1820s, and Mexico City’s hold on the territory was very weak. Tensions were growing between Mexico and Texas, and on October 2, 1835, the area erupted into violence when Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales. People just don’t take kindly to having their guns taken away in any era, I guess. The citizens of Texas chose a war for independence of allowing the government to take their guns.

Since the 17th century, Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans called it, had technically been a part of the Spanish empire. However, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas, even as late as the 1820s, and Mexico City’s hold on the territory was very weak. Tensions were growing between Mexico and Texas, and on October 2, 1835, the area erupted into violence when Mexican soldiers attempted to disarm the people of Gonzales. People just don’t take kindly to having their guns taken away in any era, I guess. The citizens of Texas chose a war for independence of allowing the government to take their guns.

Mexico had just won it’s own independence from Spain in 1821. At this point, Mexico welcomed large numbers of Anglo-American immigrants into Texas. They were hoping that these citizens would become loyal Mexican citizens, thereby keeping the territory from falling into the hands of the United States. During the next decade men like Stephen Austin brought more than 25,000 people to Texas, most of them Americans. But while these emigrants legally became Mexican citizens, they continued to speak English, formed their own schools, and had closer trading ties to the United States than to Mexico.

The situation exacerbated in 1835, the president of Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, overthrew the constitution and appointed himself dictator. Recognizing that the “American” Texans were likely to use his rise to power as an excuse to secede, Santa Anna ordered the Mexican military to begin disarming the Texans whenever possible. He underestimated the people. His attempt to disarm proved more difficult than he could have ever imagined, and the situation exploded on that October day in 1835.

That day, the Mexican soldiers were attempting to take a small cannon from the village of Gonzales. To their surprise, they encountered much stiffer resistance than they ever thought possible from a hastily assembled militia of Texans. After a rather brief fight, the Mexicans retreated and the Texans kept their cannon. The determined Texans would continue to battle Santa Ana and his army for another year and a half before winning their independence and establishing the Republic of Texas. This truly goes to show that a nation, whose citizens are armed, is much more likely to be able to fend off their enemies…even if that enemy is a tyrannous government; than an nation of disarmed citizens. Yes, the ensuing war lasted for another year and a half, but

the people won their independence in the end. They later went on to become a part of the United States, and they continue to carry their guns to this day. The people of Texas are just as adamant about their right to bear arms today as they were in 1835, as are a good number of their fellow Americans. It’s a fight that would not likely be won by the government today either. The American people won’t accept the loss of guns without a fight of epic proportions!!

the people won their independence in the end. They later went on to become a part of the United States, and they continue to carry their guns to this day. The people of Texas are just as adamant about their right to bear arms today as they were in 1835, as are a good number of their fellow Americans. It’s a fight that would not likely be won by the government today either. The American people won’t accept the loss of guns without a fight of epic proportions!!

After World War II, the GIs who had fought in the war, came home, eager to start their lives over. Many went to the car dealerships to buy new cars, only to find that there were no new cars to be found. What a bizarre thought!! In my entire lifetime, I don’t know of a time that new cars weren’t available, but there was a reason for the lack of new cars.

After World War II, the GIs who had fought in the war, came home, eager to start their lives over. Many went to the car dealerships to buy new cars, only to find that there were no new cars to be found. What a bizarre thought!! In my entire lifetime, I don’t know of a time that new cars weren’t available, but there was a reason for the lack of new cars.

During World War II, the whole United States “kicked in” on the war effort. The automobile industry changed the production in their factories from automobiles to whatever was needed for the war effort. The United States automakers manufactured a wide variety of vehicles, munitions, and more  for the government. They made tanks like the Fisher Body Grand Blanc, the Ford M10 Wolverine, and the M18 Hellcat, which were produced by the Buick Motor Car Division of General Motors. Some of the automakers were tasked with producing parts for planes, including the infamous Enola Gay. The 18-foot nose section of the fuselage was built by Chrysler. Chevrolet alone produced 60,000 engines for Pratt and Whitney cargo and bomber planes between 1942 and 1945, along with 500,000 trucks, 8 million artillery shells, and much more. The tire company, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company produced the 40 mm cannon gun mount one of which was placed on the deck of the USS Cod, while another was mounted on the

for the government. They made tanks like the Fisher Body Grand Blanc, the Ford M10 Wolverine, and the M18 Hellcat, which were produced by the Buick Motor Car Division of General Motors. Some of the automakers were tasked with producing parts for planes, including the infamous Enola Gay. The 18-foot nose section of the fuselage was built by Chrysler. Chevrolet alone produced 60,000 engines for Pratt and Whitney cargo and bomber planes between 1942 and 1945, along with 500,000 trucks, 8 million artillery shells, and much more. The tire company, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company produced the 40 mm cannon gun mount one of which was placed on the deck of the USS Cod, while another was mounted on the  stern of PT-305. Pontiac Motor Car Division built aerial launched torpedoes at its facilities in Pontiac, Michigan.

stern of PT-305. Pontiac Motor Car Division built aerial launched torpedoes at its facilities in Pontiac, Michigan.

By the time the World War II ended in 1945, the total value of goods produced by the United States auto industry for the war would exceed $29 million, equal to nearly $400,000,000 today. There had been no new cars built in the United States between early 1942 and late 1945. Once the war was over, automakers were again free to begin manufacturing new cars for the American public. That was all well and good, but it would take time to bring production of automobiles back up to speed. The first car built for civilian sale after World War II, was a Super Deluxe Ford. It rolled off the assembly line on July 3, 1945.

I recently read a book about the orphan trains, which ran between 1854 and 1929. During that time, approximately 250,000 orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children ride the train throughout the United States and Canada, to be placed with families who were looking for a child, or just as often, a worker for their farm. The orphan train movement was necessary, because at the time, it was estimated that 30,000 abandoned children were living in the streets in New York City. I had heard of the orphan trains, mostly from the movie called “Orphan Train,” but much of what really happened with those children was very new to me, and quite shocking.

I recently read a book about the orphan trains, which ran between 1854 and 1929. During that time, approximately 250,000 orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children ride the train throughout the United States and Canada, to be placed with families who were looking for a child, or just as often, a worker for their farm. The orphan train movement was necessary, because at the time, it was estimated that 30,000 abandoned children were living in the streets in New York City. I had heard of the orphan trains, mostly from the movie called “Orphan Train,” but much of what really happened with those children was very new to me, and quite shocking.

Today, while my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I were in the Black Hills, we rode the 1880 Train, as we almost always do when we are here. When they mentioned that the train had been  used in the movie “Orphan Train,” a fact that I had heard many times before, the stories from the book I had read came back to mind. My mind instantly meshed to train, the book, and the movie into one event.

used in the movie “Orphan Train,” a fact that I had heard many times before, the stories from the book I had read came back to mind. My mind instantly meshed to train, the book, and the movie into one event.

The children who traveled on the orphan trains were victims of circumstance, and they had no control over their lives at all. Each one hoped that their new family would be nice. The older ones didn’t have high hopes. The older boys pretty much knew that they would be farm hands. And most of them were right many were made to sleep in the barn, because they were thought to be thieves. If they were thieves, it was because they had to steal to survive. They did whatever it took to survive.

As Bob and I rode the train today, in the eye of my imagination, I could picture what it must have been like to be one of those orphans. The were sitting there watching that big steam engine take them to someplace they didn’t know, and probably didn’t want to go. They didn’t have high hopes for a great future, but then again, the past wasn’t that great either. They were forced to make the best of a bad situation, and the people who were in charge didn’t really care what happened to them. They were just doing their jobs. I have ridden the 1880 Train many times before, but today, it felt a little bit different, somehow. I knew that I wasn’t an orphan riding that train, but I certainly felt empathy for the children who were.

As Bob and I rode the train today, in the eye of my imagination, I could picture what it must have been like to be one of those orphans. The were sitting there watching that big steam engine take them to someplace they didn’t know, and probably didn’t want to go. They didn’t have high hopes for a great future, but then again, the past wasn’t that great either. They were forced to make the best of a bad situation, and the people who were in charge didn’t really care what happened to them. They were just doing their jobs. I have ridden the 1880 Train many times before, but today, it felt a little bit different, somehow. I knew that I wasn’t an orphan riding that train, but I certainly felt empathy for the children who were.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

Without going into all of that amazing strategy of warfare, I want to focus on one of the bombing maneuvers that took place. One of the soldiers on the ground was trying to take cover from incoming German bombs. After the bombing stopped, he looked out and was shocked to see eight bombs embedded in the ground near his foxhole. They had not gone off. He knew that it is possible for bombs to be duds, but he hadn’t heard of any American bombs that had turned out to be duds…especially eight of them at the same time, in the same place.  He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

Then the soldier made an observation that I had not considered, but that fell right into my view that not everyone in Germany agreed with Hitler. The American bomb builders were doing their job willingly. They were working to make the bombs efficient, because Germany needed to be defeated. In contrast, the German bomb builders were actually Polish slaves. Hitler had invaded their nation and was forcing them to play a part in a war that they disagreed with. The soldier considered these things and came to the conclusion that somehow the Polish slaves had been able to build a bomb that they knew would not explode, but would still pass the inspections of the Germans. The soldier believed that eight unexploded bombs could not be coincidental. It had to be sabotage.

In my research, I have seen situations where the citizens have helped the enemy, at great risk to their own safety. I have seen situations where the citizens have given aid to the enemy. And this situation was a blatant sabotage of the weapons of warfare. Within their nations, these acts were acts of treason, but they were actually fighting the evil that had tried to take over their nation. Within their confines, they were standing up for their values…for good, and for what was right. They were the enemy, in location only, because in their hearts, the were fighting for what was right, and I have to respect them for that.

War machines…the weapons of war…everything from tanks to airplanes to ships. A war cannot be fought without the equipment that transports, shoots, bombs, floats, and flies over the war. What happens to the shattered remains of the equipment that didn’t make it back to base? Obviously, if a ship is hit, it ends up at the bottom of the ocean, as does a submarine, but what of the planes, tanks, jeeps, and even the bases that have been bombed out, shot up, or otherwise rendered useless? The world is littered with the wreckage of the many wars that have taken place over the years of human existence, because humans have a propensity for fighting. We don’t like when things don’t go our way, and if we don’t understand that we can’t always have it our way, we tend to go to war.

War machines…the weapons of war…everything from tanks to airplanes to ships. A war cannot be fought without the equipment that transports, shoots, bombs, floats, and flies over the war. What happens to the shattered remains of the equipment that didn’t make it back to base? Obviously, if a ship is hit, it ends up at the bottom of the ocean, as does a submarine, but what of the planes, tanks, jeeps, and even the bases that have been bombed out, shot up, or otherwise rendered useless? The world is littered with the wreckage of the many wars that have taken place over the years of human existence, because humans have a propensity for fighting. We don’t like when things don’t go our way, and if we don’t understand that we can’t always have it our way, we tend to go to war.

On an island in the North Pacific, lies a remote island called Shikotan, at the southern end of the Kuril archipelago. The island seems like a simple place, green and lush in the summertime, but the island hides a secret. It has one particularly astonishing characteristic. The island is dotted with the decaying hulks of Russian  military tanks from the 1950s. And these rusting relics hint at the troubled past…and present of Shikotan. Shikotan is a part of an ongoing battle for ownership between Russia and Japan.

military tanks from the 1950s. And these rusting relics hint at the troubled past…and present of Shikotan. Shikotan is a part of an ongoing battle for ownership between Russia and Japan.

Shikotan is part of the Kuril archipelago, a chain of islands stretching from the southeastern tip of Russia to the north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. The Pacific lies on one side of the Kuril Islands, with the Sea of Okhotsk found on the other. Its location makes it an important island to both countries, hence the battle. After World War II, the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which was signed between the Allies and Japan in 1951, stated that Japan must give up “all right, title and claim to the Kuril Islands.” Unfortunately, it didn’t specifically recognize the Soviet Union’s sovereignty over them. That allowed the dispute that has ensued. Japan claims that at least some of the disputed islands are not a part of the Kuril Islands, and thus are not covered by the treaty. Russia maintains that the Soviet Union’s sovereignty over the islands was recognized in post-war agreements.

Since that time, Japan and the Soviet Union had been fighting over the island. They finally ended their formal state of war with the Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956, but did not resolve the territorial dispute. During talks leading to the joint declaration, the Soviet Union offered Japan the two smaller islands of Shikotan and the Habomai Islands in exchange for Japan renouncing all claims to the two bigger islands of Iturup and Kunashir, but Japan refused the offer after pressure from the US. Japan did not really intend to give up the island, and no one really knows how strong their army there was, but what is left on the island are the remnants of that army…a few masterpieces of Soviet engineering, IS-2 and IS-3 tanks.