earthquake

The quiet morning of October 1, 1987, was suddenly shattered at 7:42 am by the ominous shaking of a 6.1 earthquake. The quake, located in Whittier, California, killed 6 people and injured 100 more that fateful day. The quake, named the 1987 Whittier Narrows Earthquake, lasted 30 seconds, violently waking residents from sleep, with items tumbling to the floor. The quake ruptured gas lines, sparking several fires. As is usually the case, falling debris was the cause of the loss of lives and the injuries. In addition, there were significant highway disruptions. Remarkably, no substantial building collapses occurred despite the intense shaking. It was the largest quake to hit Southern California since 1971. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as damaging as the Northridge quake that would devastate parts of Los Angeles seven years later.

The quiet morning of October 1, 1987, was suddenly shattered at 7:42 am by the ominous shaking of a 6.1 earthquake. The quake, located in Whittier, California, killed 6 people and injured 100 more that fateful day. The quake, named the 1987 Whittier Narrows Earthquake, lasted 30 seconds, violently waking residents from sleep, with items tumbling to the floor. The quake ruptured gas lines, sparking several fires. As is usually the case, falling debris was the cause of the loss of lives and the injuries. In addition, there were significant highway disruptions. Remarkably, no substantial building collapses occurred despite the intense shaking. It was the largest quake to hit Southern California since 1971. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as damaging as the Northridge quake that would devastate parts of Los Angeles seven years later.

Southern California was shaken by a prolonged series of aftershocks in the days following the earthquake. Many people were hesitant to return to their homes, so they chose to camp in public parks for an extended period of time, until things settled down again. As a safety measure, hospitals were preemptively evacuated. While there were isolated incidents of looting amidst the turmoil, they were not widespread.

The earthquake occurred on a blind thrust fault. A blind thrust earthquake happens along a thrust fault that leaves no signs on the Earth’s surface, which is why it’s termed “blind.” These faults, hidden from view, elude standard geological mapping on the surface. Occasionally, they are detected incidentally during oil exploration with seismic methods; otherwise, their presence may remain unsuspected…until the quake occurs.

Whittier, a small town located south of Los Angeles, is primarily known as the birthplace of President Richard Nixon. However, Nixon’s birth was not the only time Whittier was in the news. In fact, this quake was not the first earthquake to strike Whittier. The 1929 Whittier earthquake struck on July 8, registering a local magnitude of 4.7 and a maximum intensity of VII (Very Strong) on the Mercalli intensity scale. The tremor, with a depth of 8.1 miles, was felt most acutely southwest of the city, where it caused significant damage to a school and two houses and led to the collapse of chimneys in other homes. In Santa Fe Springs, oil derricks were affected, and minor ground fissures were observed. That earthquake’s impact was noted from Mount Wilson to Santa Ana, and from Hermosa Beach to Riverside, with numerous aftershocks continuing until early 1931.

The 7:42 am quake was the most intense in the Los Angeles region since the 1971 San Fernando quake, reaching as far as San Diego, San Luis Obispo, and Las Vegas. Communications and local media were disrupted, power outages occurred, and many early workers were trapped in inoperative elevators. Additional

devastations included several water and gas main ruptures, broken windows, and partial ceiling collapses. Similar to the San Fernando quake, transportation was impacted, with the Santa Ana and San Gabriel River Freeways closed near Santa Fe Springs due to dislodged concrete and visible cracks. Damage from the 1987 Whittier earthquake is estimated at $100 million.

devastations included several water and gas main ruptures, broken windows, and partial ceiling collapses. Similar to the San Fernando quake, transportation was impacted, with the Santa Ana and San Gabriel River Freeways closed near Santa Fe Springs due to dislodged concrete and visible cracks. Damage from the 1987 Whittier earthquake is estimated at $100 million.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

It was a typical lunch hour in Japan’s capital city of Tokyo, and the neighboring “City of Silk” Yokohama that September 1, 1923. People were out and about doing their normal lunchtime things, eating and running errands before going back to work. Suddenly the days routine was shattered when a massive, 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck just before noon. The shaking lasted just 14 seconds, but that was all it took to bring down nearly every building in Yokohama, which is just south of Tokyo. The shaking also caused more than half of Tokyo’s brick buildings, most of Yokohama’s buildings, and hundreds of thousands of homes to collapse, killing tens of thousands of people instantly.

Known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, but also called the Tokyo-Yokohama Earthquake, of 1923, it caused an estimated death toll of more than 140,000 and left some 1.5 million people homeless, according to reported numbers. Following the earthquake came another disaster in the form of fires that burned many buildings. Most likely, this was because in 1923, people cooked over an open flame, and the quake struck while people were preparing lunch. To further complicate matters, the area was hit by high winds, caused by a typhoon that passed off the coast of the Noto Peninsula in northern Japan, spread the flames and created horrifying firestorms. Because the quake had snapped water mains, the fires could not be extinguished until September 3rd. By that time, about 45 percent of Tokyo had burned. Some researchers believed that the typhoon may have triggered the earthquake, because the forced atmospheric pressure pressed on a stressed and delicate fault line of three major tectonic plates that meet under Tokyo. I wasn’t aware that this was possible, but  apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

apparently it is. The quake also triggered a tsunami that swelled to 39.5 feet at Atami on the Sagami Gulf, where 60 people were killed and 155 homes destroyed.

The damage from all this in Toyko was so severe that some government leaders argued for moving the Japanese capital to a new city. Educator, Miura Tosaku toured the destruction of Tokyo in the fall of 1923, concluded that the earthquake was an apocalyptic revelation. He wrote: “Disasters take away the falsehood and ostentation of human life and conspicuously expose the strengths and weaknesses of human society.” Tenrikyo relief worker Haruno Ki’ichi said, “The destruction and devastation in the earthquake aftermath surpassed imagination.”

Yokohama’s Victorian-era Grand Hotel, that had hosted famous people including US President William Howard Taft and English author Rudyard Kipling, completely collapsed. Hundreds of hotel employees and guests were crushed. Henry W Kinney, a Tokyo-based editor of the Trans-Pacific publication, observed the devastation in Yokohama hours after the earthquake hit. He wrote, “Yokohama, the city of almost half a million souls, had become a vast plain of fire, of red, devouring sheets of flame which played and flickered. Here and there a remnant of a building, a few shattered walls, stood up like rocks above the expanse of flame, unrecognizable … It was as if the very Earth were now burning. It presented exactly the aspect of a gigantic Christmas pudding over which the spirits were blazing, devouring nothing. For the city was gone.”

Since 1960, the Japanese people recognize the September 1 anniversary of the earthquake as Disaster Prevention Day. It’s a noble idea, but I’m not sure how these disasters could be prevented, other than the now common practice of earthquake proofing buildings to prevent so much loss. Nevertheless, Japan has suffered through several more devastating earthquakes. More than seven decades after the 1923 disaster, an earthquake struck Kobe on January 17, 1995. This Kobe Earthquake caused an estimated 6,400 deaths, widespread fires, and a landslide in Nishinomiya. Then, on March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude temblor struck off th

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

e coast of Japan’s city of Sendai. This Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami caused a series of catastrophic tsunamis in Japan, and more than 18,000 estimated deaths. I suppose that to say the very least, the loss of life in these more recent quakes, was far less than in the original event that founded Disaster Prevent Day.

The shaking began at 9:51pm that August 31, 1886, and by the time it was over, more than 100 people in Charleston, South Carolina would be dead and hundreds of buildings were destroyed. It wasn’t that there were no warnings. There were…unheeded warnings in the form of two foreshocks that were felt in Summerville, South Carolina, on August 27th and 28th, but no one was prepared for the strength of the August 31 quake. The quake was felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, and even Cuba. Buildings were damaged as far away as Ohio and Alabama.

The shaking began at 9:51pm that August 31, 1886, and by the time it was over, more than 100 people in Charleston, South Carolina would be dead and hundreds of buildings were destroyed. It wasn’t that there were no warnings. There were…unheeded warnings in the form of two foreshocks that were felt in Summerville, South Carolina, on August 27th and 28th, but no one was prepared for the strength of the August 31 quake. The quake was felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, and even Cuba. Buildings were damaged as far away as Ohio and Alabama.

Even with all that, it was Charleston, South Carolina that took the biggest hit from the quake. While quake measurements in those days were not as accurate as they are these days, this quake was thought to measure a magnitude of about 7.6. Almost all of the buildings in Charleston were seriously damaged. Approximately 14,000 chimneys fell from the earthquake. Multiple fires erupted, and water lines and wells were ruptured. The total damage was in excess of $5.5 million in those days, which would figure to approximately $115 million today. The greatest damage was done to buildings constructed out of brick, which amounted to 81% of building damage. The frame buildings suffered significantly less damage. Another factor that came into play was kind of  ground these buildings were built on. Buildings constructed on ground that had been built up to accommodate them (made ground), suffered significantly more damage than buildings constructed on solid ground, however, this relationship only occurred in wood-frame buildings. Approximately 14% of wood-frame buildings built on “made ground” sustaining damage, compared to 0.5% of wood-frame buildings built on solid ground sustaining damage.

ground these buildings were built on. Buildings constructed on ground that had been built up to accommodate them (made ground), suffered significantly more damage than buildings constructed on solid ground, however, this relationship only occurred in wood-frame buildings. Approximately 14% of wood-frame buildings built on “made ground” sustaining damage, compared to 0.5% of wood-frame buildings built on solid ground sustaining damage.

The residential buildings sustained significantly less damage than the more prominent commercial buildings, most of which were destroyed, or nearly so. This was due to the fact that commercial buildings were older, had a more prominent top compared to the base of the building, and were made of brick. The Old White Meeting House near Summerville, South Carolina was reduced to ruins. Many of the other man-made structures were also damaged as a result of earth splits caused by the earthquake. The railroad tracks in Charleston and nearby areas were snapped and trains were derailed. In addition, flooding occurred in surrounding farms and roads when dams broke. Acres of land actually liquefied in many spots, which further damaged many buildings, roads, bridges, and farm fields.

Strangely, for an earthquake of this magnitude anyway, was the fact that there were no apparent surface cracks as a result of this tremor, but railroad tracks were bent in all directions in some locations. The true cause of this quake remained a mystery for many years, because there were no known underground faults for 60

miles in any direction. However, now, with better science and detection methods, scientists have recently uncovered a “concealed fault” along the coastal plains of Virginia and the Carolinas. While there is now a known fault, a quake of this magnitude is highly unlikely in this location. Nevertheless, this was the largest recorded earthquake in the history of the southeastern United States.

miles in any direction. However, now, with better science and detection methods, scientists have recently uncovered a “concealed fault” along the coastal plains of Virginia and the Carolinas. While there is now a known fault, a quake of this magnitude is highly unlikely in this location. Nevertheless, this was the largest recorded earthquake in the history of the southeastern United States.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

At that time, San Francisco’s had a variety of brick buildings and wooden Victorian structures that were not really earthquake reinforced. Nobody knew about making buildings strong enough to resist destruction from an earthquake. It was one of the things we would learn from the results of a disaster. It seems that with each disaster, we learn how to prevent the loss of so many buildings and lives. The old buildings were devastated. Along with the collapsed buildings, came devastating fires, and because many of the water mains had broken, firefighters were prevented from stopping  the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

As significant aftershocks continued, firefighters and US troops fought desperately to control the ongoing fires. Sadly, that sometimes meant dynamiting whole city blocks to create firewalls. Many people were trapped where they were, because the fires prevented their escape, even though they were not stuck in a collapsed building. Finally, on April 20th, several thousands of refugees were evacuated from the foot of Van Ness Avenue. The army would eventually house 20,000 refugees in more than 20 military-style tent camps across the city. The people had no idea how long they might have to be there.

Most of the fires were extinguished by April 23rd, and the authorities started the task of rebuilding the devastated city. In all, approximately 3,000 people lost their lives as a result of the Great San Francisco Earthquake and the devastating fires it inflicted upon the city. Almost 30,000 buildings were destroyed, including most of the city’s homes and nearly all the central business district. The rebuilding would take a long time, and the new structures were reinforced to be able to better withstand the shaking of the San Andreas fault. This quake may not have been the “Big One” that is predicted, but at an estimated 7.9 or 8.0, it was right up there.

These days, we have early warning alarms for tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and even tsunamis, but on July 21, 365, no such warnings existed, not did any kind of measuring tools so we could know the magnitude of the earthquake that caused tsunamis, or the height of the tsunami itself. Nevertheless, it is known that a powerful earthquake off the coast of Greece caused a tsunami that devastated the city of Alexandria, Egypt.

These days, we have early warning alarms for tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and even tsunamis, but on July 21, 365, no such warnings existed, not did any kind of measuring tools so we could know the magnitude of the earthquake that caused tsunamis, or the height of the tsunami itself. Nevertheless, it is known that a powerful earthquake off the coast of Greece caused a tsunami that devastated the city of Alexandria, Egypt.

In spite of the lack of measuring tools at the time, scientists can now estimate that the earthquake was actually two quakes in quick succession. It is estimated that the largest of those quakes was about a magnitude of 8.0. That magnitude of quake is massive by any standards, and it must have been very scary for anyone who might have felt it. It’s hard to say how many people actually felt it, because of its oceanic location, but even if no one felt the quake, they very much felt the aftereffects of that quake. The really tragic thing was that they had no idea what was coming their way, how very dangerous it was, or even that they should run when they saw it coming. I’m sure that they had seen tides come in and go out, and even storms bringing big wave onto the shore. So, it is very possible that they thought this was not that different than those things, except for it not being time for the tide and there was no storm. They likely just stood there looking at this strange phenomenon, until it took them all out.

The quake was centered near a plate boundary called the Hellenic Arc. Following the quake, a wall of water ran across the Mediterranean Sea toward the Egyptian coast. As happens in tsunamis, the water first recedes, and then comes crashing back. As the water in the harbor receded, ships docked at Alexandria suddenly overturned. As often happens in a disaster, it was reported that many people rushed out to loot the overturned ships. That put even more people in harm’s way. The tsunami wave then rushed in and carried the ships over the sea walls, landing many on top of buildings. The people were trapped, and in Alexandria alone, on that one day, approximately 5,000 people lost their lives, and 50,000 homes were destroyed.

The destruction was even greater in the surrounding villages and towns. Many of these small villages were literally wiped of the face of the earth. Outside of Alexandria, 45,000 people were killed. The salty sea water, inundation the farmlands, rendering them useless for years. From what scientists are able to piece together, the area’s shoreline was permanently changed by the disaster. The tsunami continued on, slowly, but steadily

overtaking the buildings of Alexandria’s Royal Quarter. The main reason that the archaeologists learned about this horrific event was that in 1995 that archaeologists actually discovered the ruins of the old city, which lies off the coast of present-day Alexandria. With the changed shoreline following the tsunami, many of the old buildings remained under water for centuries.

overtaking the buildings of Alexandria’s Royal Quarter. The main reason that the archaeologists learned about this horrific event was that in 1995 that archaeologists actually discovered the ruins of the old city, which lies off the coast of present-day Alexandria. With the changed shoreline following the tsunami, many of the old buildings remained under water for centuries.

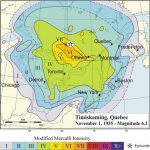

I suppose that if I lived in Quebec, Canada, I might have heard the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region and maybe even the Western Quebec Seismic Zone. Since I don’t, these areas are new to me. Maybe they were new to a lot of people, but on November 1, 1935, a lot more people knew about them. On that day, a 6.1 magnitude earthquake with a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (Very strong) occurred. The epicenter occurred on a thrust fault in the Timiskaming Graben, a little over 6 miles northeast of Témiscamingue, at about 1:03am ET.

I suppose that if I lived in Quebec, Canada, I might have heard the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region and maybe even the Western Quebec Seismic Zone. Since I don’t, these areas are new to me. Maybe they were new to a lot of people, but on November 1, 1935, a lot more people knew about them. On that day, a 6.1 magnitude earthquake with a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (Very strong) occurred. The epicenter occurred on a thrust fault in the Timiskaming Graben, a little over 6 miles northeast of Témiscamingue, at about 1:03am ET.

While the earthquake was in Canada, it was felt over a wide area of North America, extending west to Fort William (now Thunder Bay), east to Fredericton, New Brunswick, north to James Bay and south as far as Kentucky and West Virginia. Occasional aftershocks were reported for several months. That seems extreme for a 6.1 magnitude earthquake, but I suppose it’s all in the connections. Fault lines aren’t just in a small area, they run for hundreds and even thousands of miles.

The most significant damage from the earthquake, both in the immediate area and as far south as North Bay and Mattawa, was to chimneys. In fact, 80% of the chimneys in that area were destroyed. A railroad embankment near Parent, which is 186 miles away, also collapsed. It looked like the embankment slide was already imminent, but the quake vibrated the last holds loose. There were some rockfalls and structural cracks reported as well. Thankfully, there were few major structural collapses aside from the Parent embankment. The

sparseness of the area’s population played a big part in the relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake. The water of Tee Lake, close to the epicenter was discolored by the earthquake…due to a stirring up of gyttja, which is freshwater mud with abundant organic matter, rather than silt input from tributary streams. The relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake, has been attributed primarily to the sparseness of the area’s population.

sparseness of the area’s population played a big part in the relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake. The water of Tee Lake, close to the epicenter was discolored by the earthquake…due to a stirring up of gyttja, which is freshwater mud with abundant organic matter, rather than silt input from tributary streams. The relative lack of major damage, despite the fact that it was a strong earthquake, has been attributed primarily to the sparseness of the area’s population.

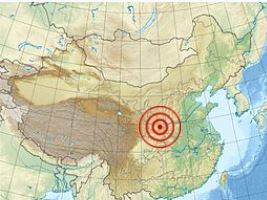

Most of us realize that there are earthquakes going on all the time. Most of them are very small, and often not even felt by anyone. Some are so far out in the ocean that they have little effect of anything. Others are far out in the wilderness or unpopulated areas, and so no one feels them. There are, however, some that are so large and so devastating, that they can never be forgotten. The January 23, 1556 earthquake in Shaanxi, China is just such an earthquake.

Most of us realize that there are earthquakes going on all the time. Most of them are very small, and often not even felt by anyone. Some are so far out in the ocean that they have little effect of anything. Others are far out in the wilderness or unpopulated areas, and so no one feels them. There are, however, some that are so large and so devastating, that they can never be forgotten. The January 23, 1556 earthquake in Shaanxi, China is just such an earthquake.

The earthquake struck Shaanxi late in the evening, and the aftershocks continuing through the following morning. I’m not sure how the scientists can calculate the magnitude years later, but their investigation revealed that the magnitude of the quake was approximately 8.0 to 8.3. That is, by no means, the strongest quake on record, but it struck right in the middle of a densely populated area with poorly constructed buildings and homes, resulting in a horrific death toll. Making buildings earthquake proof in the 1500s was not even a possibility…at least not to the level of the current building codes. Because of that, the death toll was estimated at a staggering 830,000 people. Of course, counting casualties is often imprecise after large-scale disasters, especially prior to the 20th century. Nevertheless, this disaster is still considered the deadliest of all time.

The earthquake’s epicenter was in the Wei River Valley in the Shaanxi Province, near the cities of Huaxian,  Weinan and Huayin. In Huaxian alone, every single building and home collapsed, killing more than half the residents of the city. The death toll there was estimated in the tens of thousands. Similarly, the death toll and economic impact in Weinan and Huayin was also very high. There were places where 60-foot-deep crevices opened in the earth. Serious destruction and death occurred as much as 300 miles away from the epicenter. The earthquake triggered landslides, which also contributed to the massive death toll. Of course, the estimates could be off, but even if the number of deaths caused by the Shaanxi earthquake has been overestimated slightly, it would still rank as the worst disaster in history by a considerable margin.

Weinan and Huayin. In Huaxian alone, every single building and home collapsed, killing more than half the residents of the city. The death toll there was estimated in the tens of thousands. Similarly, the death toll and economic impact in Weinan and Huayin was also very high. There were places where 60-foot-deep crevices opened in the earth. Serious destruction and death occurred as much as 300 miles away from the epicenter. The earthquake triggered landslides, which also contributed to the massive death toll. Of course, the estimates could be off, but even if the number of deaths caused by the Shaanxi earthquake has been overestimated slightly, it would still rank as the worst disaster in history by a considerable margin.

For many years my husband’s Aunt Marian and Uncle John Kanta lived in Helena, Montana. Some of their kids still do, but they didn’t live there in 1935, when on October 18th, a magnitude 6.2 earthquake struck at 10:48pm. The quake had its epicenter right near Helena and it had a maximum perceived intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale. The quake on that date was the largest of a series of earthquakes that also included a large aftershock on October 31 of magnitude 6.0 and a maximum intensity of VIII. Two people died in the first quake, and two others died as a result of the October 31 aftershock. Property damage was over $4 million.

For many years my husband’s Aunt Marian and Uncle John Kanta lived in Helena, Montana. Some of their kids still do, but they didn’t live there in 1935, when on October 18th, a magnitude 6.2 earthquake struck at 10:48pm. The quake had its epicenter right near Helena and it had a maximum perceived intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale. The quake on that date was the largest of a series of earthquakes that also included a large aftershock on October 31 of magnitude 6.0 and a maximum intensity of VIII. Two people died in the first quake, and two others died as a result of the October 31 aftershock. Property damage was over $4 million.

Helena is a pretty city that lies in a valley in western Montana. It lies within the northern part of the Intermountain Seismic Belt (ISB). I didn’t know it then, but this is an area of relatively intense seismicity. It runs from northwestern Arizona, through Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming, before dying out in northwestern Montana. In the area near Helena, it turns to the northwest, where it intersects with the Lewis and Clark fault zone. The Helena earthquake sequence actually began October 3, 1935, with a small earthquake. That quake was followed by a damaging earthquake on October 12th, a magnitude 5.9, intensity VII. That wasn’t the mainshock, however. That one occurred on October 18th, a magnitude 6.2, intensity VIII. A lesser shock followed on October 31st, a magnitude 6.0, intensity VIII, and a further large aftershock on November 28th, a magnitude 5.5, intensity VI. These were just the mainshocks. There were also a total of 1800 tremors recorded  between October 4, 1935 and April 30, 1936. The people of Helena either got used to the shaking, which I can’t imagine, or they were terrified with every tremor, which makes more sense to me.

between October 4, 1935 and April 30, 1936. The people of Helena either got used to the shaking, which I can’t imagine, or they were terrified with every tremor, which makes more sense to me.

The damage to the unreinforced buildings of that era was widespread, with more than 200 chimneys destroyed in the city of Helena. At that time, little was known about reinforcement of buildings in earthquake prone areas. The northeast part of the city, where buildings were constructed on alluvial soil, and in the southern business district, which contained many brick buildings, saw the strongest effects. Alluvial soil is highly porous, which would explain the soil liquification that took place. The most extensively damaged building was the Helena High School, which was completed in August 1935 and had just been dedicated in early October. The school buildings, which had cost $500,000, had not been designed to be earthquake resistant. Another building that was totally destroyed and had to be rebuilt was the Lewis and Clark County Hospital. The October 18 earthquake caused an estimated $3 million of damage to property. The aftershock of October 31 caused further damage estimated at $1 million, particularly to structures already weakened by the October 18 shock. Two people were killed by falling bricks in Helena during the October 18 shock. Two brick masons died as while removing a brick tower during the October 31 aftershock.

The Red Cross and Federal Emergency Relief Administration set up emergency camps for those displaced by the quake on land at the Montana Army National Guard’s Camp Cooney. Approximately 400 people stayed there the first night, but most had found space with friends or family outside of the damaged area by the end of the week. Some people were too afraid of continued shocks to stay in a house, and they stayed in tents for the next few weeks. The National Guard was deployed in Helena to keep sightseers away from the damaged buildings, and either because of the guard or the good moral values of the people, there was no looting. It is believed that in today’s world, the damages would have been in the $500 million range.

The Red Cross and Federal Emergency Relief Administration set up emergency camps for those displaced by the quake on land at the Montana Army National Guard’s Camp Cooney. Approximately 400 people stayed there the first night, but most had found space with friends or family outside of the damaged area by the end of the week. Some people were too afraid of continued shocks to stay in a house, and they stayed in tents for the next few weeks. The National Guard was deployed in Helena to keep sightseers away from the damaged buildings, and either because of the guard or the good moral values of the people, there was no looting. It is believed that in today’s world, the damages would have been in the $500 million range.

The earthquake struck at 5:35pm local time on Good Friday, March 27, 1964. Its epicenter was 12.4 miles north of Prince William Sound, 78 miles east of Anchorage and 40 miles west of Valdez. Across southcentral Alaska, ground fissures, collapsing structures, and tsunamis resulting from the earthquake caused about 131 deaths. Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property. Anchorage was hit very hard, and sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment, particularly in the several landslide zones along Knik Arm. Two hundred miles southwest, some areas near Kodiak were permanently raised by 30 feet. Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of Turnagain Arm near Girdwood and Portage dropped as much as 8 feet, requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the Seward Highway above the new high tide mark.

The earthquake struck at 5:35pm local time on Good Friday, March 27, 1964. Its epicenter was 12.4 miles north of Prince William Sound, 78 miles east of Anchorage and 40 miles west of Valdez. Across southcentral Alaska, ground fissures, collapsing structures, and tsunamis resulting from the earthquake caused about 131 deaths. Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property. Anchorage was hit very hard, and sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment, particularly in the several landslide zones along Knik Arm. Two hundred miles southwest, some areas near Kodiak were permanently raised by 30 feet. Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of Turnagain Arm near Girdwood and Portage dropped as much as 8 feet, requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the Seward Highway above the new high tide mark.

I came to know of this horrific 9.2 magnitude earthquake when my husband, Bob and I were on a cruise to Alaska. The cruise ended in Anchorage, and we had taken an extra day for exploration of the area. My first notice of this Alaskan earthquake was on a shuttle ride from the airport to Anchorage proper. We had the day before our flight at 10:30pm, so we stored our luggage at the airport and took the shuttle back into town. The shuttle driver took us by the Turnagain Heights neighborhood, the current location of Earthquake Park. She told us that the soil there had liquified and homes were swallowed…some almost completely, leaving only their chimneys above ground, while others were swept out to sea in the ensuing tsunami waves. I couldn’t shake the dreadful feeling of the horror that had happened there. A stop in a museum, including a documentary about the 1964 Alaskan earthquake, told me that the earthquake that happened in the modern-day Earthquake Park, was the 1964 Alaskan earthquake. Of course, I was only 8 years old when it happened, so I guess that it is not so odd that I hadn’t heard of it.

We began a much longer than expected walk along the Tony Knowles Coastal Bicycle Trail. Of course, people were walking on the trail too, but we had no idea how long the walk back to the airport would be. Nevertheless, the walk took us through Earthquake Park, and…well, I have only noticed such an air of heaviness in one other place…Gettysburg Battlefield. There is something about being in a place where so much death and destruction occurred. I takes on an air of being “hallowed ground” somehow. President Lincoln knew what he was talking about when he gave the Gettysburg Address. Walking through Earthquake Park, you could see the rippled ground, where the liquified soil had rolled back and forth during the earthquake. We didn’t get off the trail, so if there were chimneys visible near us, we didn’t see them, but I was moved to think that beneath our feet, there might be houses that people had lived in. I didn’t know if the people who had lived there were there still, or if

they had been located and buried after the disaster. Whatever the case may be, I left the area feeling very different than I had just two days earlier. I had been in the exact place where such a devastating disaster had happened, and I have never forgotten that place, just as I have never forgotten the feeling I felt at Gettysburg. Some things just have a profound effect on us…forever.

they had been located and buried after the disaster. Whatever the case may be, I left the area feeling very different than I had just two days earlier. I had been in the exact place where such a devastating disaster had happened, and I have never forgotten that place, just as I have never forgotten the feeling I felt at Gettysburg. Some things just have a profound effect on us…forever.

Imagine, if you can these days, a world without photography. Cameras are almost always at our fingertips now. We don’t need to carry a camera with us, we have our phones, and we are able to take all the pictures we want. We can document everything from the birth of our children, to a pretty sunset in the back yard. We document our smiles, frowns, and totally shocked looks. In so many ways, personal photography has changed our lives, but one way in particular is in documenting history. Most people don’t think our what they are doing as documenting history exactly, but it certainly can be. People have captured plane crashes, rocket launches, car accidents, forest fires, volcano eruptions, and earthquakes…just to name

Imagine, if you can these days, a world without photography. Cameras are almost always at our fingertips now. We don’t need to carry a camera with us, we have our phones, and we are able to take all the pictures we want. We can document everything from the birth of our children, to a pretty sunset in the back yard. We document our smiles, frowns, and totally shocked looks. In so many ways, personal photography has changed our lives, but one way in particular is in documenting history. Most people don’t think our what they are doing as documenting history exactly, but it certainly can be. People have captured plane crashes, rocket launches, car accidents, forest fires, volcano eruptions, and earthquakes…just to name  a few. Those things might not be history today, but in a couple of years, they are, and in many cases, one person had the only picture of the historic event.

a few. Those things might not be history today, but in a couple of years, they are, and in many cases, one person had the only picture of the historic event.

Would history be documented without photography? Of course, but it would happen by word of mouth, and later the written word…newspapers, books and such. The problem with that is that those accounts can only tell the part of history that someone saw or was a part of. But, what if they missed something? Humans so often miss the small details, but a camera or video camera, doesn’t miss as much. Once a picture is taken, an event is documented…and every small detail can be re-examined at will. Pictures have made the difference between knowing the cause and never knowing the cause. Pictures have proven fault  without a doubt. They have been the difference between an innocent person being falsely accused, and getting to the truth.

without a doubt. They have been the difference between an innocent person being falsely accused, and getting to the truth.

These days, with a camera built into our phone, we can, and do, document many events of our lives. And we document history…some of it amazing, and some of it devastating. It’s all part of the ability to capture things in real time. You have to take the bad with the good, because unfortunately, not all of history is beautiful. Some of it is completely ugly, but it still needs to be documented. Pictures have become necessary, because without photography, much of the full documentation of history would be lost.