Values

There are men of war, and then there are men of war. United States General George S Patton was the latter…meaning that he almost lived for war. Patton was a man who came from a long line of military people, and while he wasn’t always a tactful man, he was a great warrior…a fact that he proved over and over again. Many people didn’t like him much, but they couldn’t deny his capabilities. Patton was a great leader, but he wasn’t really a people person, and that got him in some trouble.

There are men of war, and then there are men of war. United States General George S Patton was the latter…meaning that he almost lived for war. Patton was a man who came from a long line of military people, and while he wasn’t always a tactful man, he was a great warrior…a fact that he proved over and over again. Many people didn’t like him much, but they couldn’t deny his capabilities. Patton was a great leader, but he wasn’t really a people person, and that got him in some trouble.

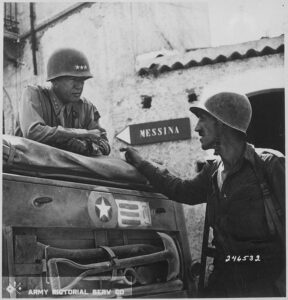

George Smith Patton Jr, who was born to George Smith Patton Sr and his wife, Ruth Wilson, the daughter of Benjamin Davis Wilson on November 11, 1885, in San Gabriel, California. Maybe because of his family history, or maybe it was just him, but Patton never seriously considered a career other than the military. At the age of seventeen he tried for an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He also applied to several universities with Reserve Officer’s Training Corps programs, and was accepted to Princeton College, but eventually decided on Virginia Military Institute (VMI), which his father and grandfather had attended. Later, after studying at West Point, he served as a tank officer in World War I. Patton loved the tank, and his time as a tank officer, as well as his military strategy studies led him to become an advocate of the crucial importance of the tank in future warfare. When the United States entered World War II, Patton became the logical choice for the command of an important US tank division, and his division played a key role in the Allied invasion of French North Africa in 1942. Then, in 1943, in the Allied assault on Sicily, Patton and the US 7th Army in its assault on Sicily and won fame for out-commanding Montgomery during their pincer movement against Messina. Patton loved competition, and this was his chance to shine. On August 17, 1943, Patton and his 7th Army arrived in Messina several hours before British Field Marshal Bernard L Montgomery and his 8th Army, winning the unofficial “Race to Messina” and completing the Allied conquest of Sicily.

Although Patton was one of the most capable American commanders in World War II, he was also one of the most controversial. Patton was a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” kind of guy, and therefore had no personal understanding of fear or fatigue. PTSD, battle fatigue, or shell shock were conditions he could not accept in anyone. In fact, they infuriated him so much that he actually slapped two soldiers who were suffering with the conditions. During the Sicilian campaign, Patton generated considerable controversy when he accused a hospitalized US soldier suffering from battle fatigue of cowardice and then personally struck him across the face. The famously profane general was forced to issue a public apology and was reprimanded by General Dwight Eisenhower. They would have liked to “walk away” from Patton, but when it came time for the invasion of Western Europe, Eisenhower couldn’t find a general as formidable as Patton, so, once again Patton was granted an important military post. In 1944, Patton commanded the US 3rd Army in the invasion of France. Then, in

December of that year Patton’s great expertise in military movement and tank warfare helped to crush the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes.

December of that year Patton’s great expertise in military movement and tank warfare helped to crush the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes.

During one of his many successful campaigns, General Patton was said to have declared, “Compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance.” Patton died in a hospital in Germany on December 21, 1945, from injuries sustained in an automobile accident near Mannheim. He was just 60 years old.

My brother-in-law, LJ Cook was an MP in the Army from 1968 to 1971, which was the Vietnam Era. For a long time, that was all I knew about his time of service. Today, that has all changed. I think I thought of MPs as maybe handling the disobedient military personnel, maybe like the movie, “Stripes” or the show, “MASH,” but movies rarely tell the whole story on these things. LJ went through basic training in Fort Ord, located in the Monterey Bay area of California. Following his basic training, LJ was sent to MP school at Fort Gordon located southwest of Atlanta, Georgia. Following his MP training, LJ flew into Frankfort, Germany, and then on to Mannheim, Germany, where he would spend the remainder of his military service as an MP at the Mannheim Prison.

My brother-in-law, LJ Cook was an MP in the Army from 1968 to 1971, which was the Vietnam Era. For a long time, that was all I knew about his time of service. Today, that has all changed. I think I thought of MPs as maybe handling the disobedient military personnel, maybe like the movie, “Stripes” or the show, “MASH,” but movies rarely tell the whole story on these things. LJ went through basic training in Fort Ord, located in the Monterey Bay area of California. Following his basic training, LJ was sent to MP school at Fort Gordon located southwest of Atlanta, Georgia. Following his MP training, LJ flew into Frankfort, Germany, and then on to Mannheim, Germany, where he would spend the remainder of his military service as an MP at the Mannheim Prison.

Construction on Mannheim Prison was started in 1905 and it first opened for use in 1909. It was a Third Reich prison until after World War II. Then it was used for United States military purposes during the Vietnam War. The prison included a separate hospital building, which until 1945 was used to treat ill prisoners throughout the region. The prison was considered modern for the time, with each cell having running water with a toilet and a washbasin, central heating and electric light. As with all prisons in Third Reich Germany, Mannheim Prison was used to incarcerate standard criminal convicts as well as political prisoners.

LJ was a Maximum Confinement Section Chief during his time at Mannheim Prison. The correctional officers lived in the barracks on site during their off time. LJ was part of the 77th MP Company, which at that time was the biggest company in army. The prison also had two chapels, two mess halls, and it was a large enough place that LJ didn’t know everyone stationed there…even after three years. When an MP first arrives at Mannheim Prison, they are settled into the squad bay in the attic of the barracks. This is really temporary housing until they can be officially assigned. Most of the rooms in the main barracks (specifically for the Non-NCO personnel) have four men to a barracks. The NCOs had two men to a room. And the higher-ranking officers had a private room. Lynn’s highest rank was that of Acting E7, but his permanent rank was Seargent. He could have been given the permanent rank of E7, if he had wanted to re-enlist for six more years. He did not. He would have also been sent to Vietnam had he re-enlisted.

During his time at Mannheim Prison, LJ saw three or four prison riots, all of which the MPs squashed. The prisoners at Mannheim Prison were American GIs in prison for everything from being AWOL to murder. Of course, riots happened when the prisoners overpowered a guard. That seems like an unlikely possibility, but the prison, with four blocks, A, B, C, and D, with each block having 8 cells, each holding 30 to 40 prisoners. Cells were made of steel bars so, no privacy. A guard was sometimes in the cell with the men, and you just didn’t take a gun in there, on the off chance that a prisoner could take it from you. The guards were armed with night sticks, as their only weapon. During the riots, while LJ was there, no guards were killed, but there were a number of incidences in which guards were beaten. LJ was once hit in the head by a boot thrown at him by a prisoner. LJ had to hit the man with his night stick. In defending himself, LJ dislocated the man’s shoulder and broke his collar bone. Needless to say, the man never threw a boot at LJ again.

Another part of LJ’s job was to make arrangements for shipments of prisoners from Mannheim Prison to Leavenworth Prison, in northeastern Kansas. Leavenworth is now a medium security US penitentiary. LJ made eight trips across the Atlantic with shipments of prisoners. One onboard, LJ was in charge of everything on the plane. The prisoners were not handcuffed or otherwise restrained, and there were no bars or cages between prisoners and guards. Sometimes the whole plane was full of guards and prisoners. When the made fueling stops, the prisoners had to get off. The airports had to be notified upon landing so they could bring out extra security to prevent escape. The prisoners thought LJ was crazy. He told them that he would take action is they tried to escape, and that he was a bad shot. He said that while trying to “wound” escaping prisoners, but that he almost aways missed and hit the prisoner in the back of the head. Needless to say, LJ never lost a prisoner. After the guards transported prisoners, they got two weeks leave, so he would usually head home to Lovell, Wyoming for a home visit. The military license said that he had said “no time or mileage limitation.” That meant that he could go wherever he wanted, so if he was not going home, he might get a taxi to a train station, and then head out to wherever he wanted to see at the time. He also had a friend who was a warrant officer, who piloted a Huey Helicopter. On days off, they would jump in the Huey and go all over Europe and even northern Africa. The “normal work week” in the Army was a “twelve day” week. The men had three days on day shift

followed by 24 hours off. Then they had three days on swing shift followed by 24 hours off, and finally three days on night shift followed by 24 hours off. It gave them time to have some R and R every few days. The two weeks for leave were the normal 14 days. LJ was honorably discharged from the Army in 1971. His training would help him in his career as a Deputy Sheriff in Casper, Wyoming. I would like to thank my brother-in-law, LJ Cook for his service to his country. Today is LJ’s birthday. Happy birthday LJ!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

followed by 24 hours off. Then they had three days on swing shift followed by 24 hours off, and finally three days on night shift followed by 24 hours off. It gave them time to have some R and R every few days. The two weeks for leave were the normal 14 days. LJ was honorably discharged from the Army in 1971. His training would help him in his career as a Deputy Sheriff in Casper, Wyoming. I would like to thank my brother-in-law, LJ Cook for his service to his country. Today is LJ’s birthday. Happy birthday LJ!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Captain Leonard Treherne “Max” Schroeder Jr looked out over the choppy water between the landing craft he was on and the shores of their destination…the beaches of Normandy, France. The beaches had been given code names, to protect the mission…Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword; the operation was code named Overlord. The beach ahead of Schroeder had been code named Utah. Along the hills behind the beach were many German bunkers, with armed German snipers hiding inside of them. Schroeder knew they were just waiting for them to step onto the beach before the snipers would open fire.

Captain Leonard Treherne “Max” Schroeder Jr looked out over the choppy water between the landing craft he was on and the shores of their destination…the beaches of Normandy, France. The beaches had been given code names, to protect the mission…Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword; the operation was code named Overlord. The beach ahead of Schroeder had been code named Utah. Along the hills behind the beach were many German bunkers, with armed German snipers hiding inside of them. Schroeder knew they were just waiting for them to step onto the beach before the snipers would open fire.

Schroeder was about to find out firsthand, just how bad this day was going to be. In fact, he was the first American soldier whose feet hit the sand on the beach at Normandy on D-Day…so, while his men were right behind him, he would experience this horrific battle at its inception. I have wondered just how they knew that he was first amid all that chaos, but it is a documented fact. Operation Overlord was pivotal in the United States’ overall success, but it was also extremely bloody, with great loss of life. While every life lost was horrific, the men who stormed the beaches of Normandy that day were willing to give their lives for a  cause that they felt was essential…and I have so much respect for each and every one of them. Captain Schroeder led his team of men onto the beach…along with thousands of others…and managed to get them to their secured location. Nevertheless, during the mission, he was shot twice by German snipers. Once the mission was accomplished and his men were where they needed to be, Captain Schroeder passed out from his injuries.

cause that they felt was essential…and I have so much respect for each and every one of them. Captain Schroeder led his team of men onto the beach…along with thousands of others…and managed to get them to their secured location. Nevertheless, during the mission, he was shot twice by German snipers. Once the mission was accomplished and his men were where they needed to be, Captain Schroeder passed out from his injuries.

Schroeder woke up at an aid station on the beach, with medics taking care of his wounds so he could be transported to an army hospital in England. While in England, he recovered and had a lot of time to read all about his role in the successful mission…in many papers. I don’t know if he realized that his had been such a pivotal role in the battle, but it had. At the time, I doubt if he thought he would ever see that beach again, but in 1994, Schroeder revisited the beach at Normandy as a guest of the French  government. It was an amazing ceremony to pay homage to his heroic efforts that helped turn the tide for the Allies in World War II. It was an honor he had given no thought to as he looked out at that beach on that long ago June 6, 1944…but, an honor that he had earned along with all the other men who fought, and the many who had died. I’m sure those who gave all, were thankful that some made it home and managed to live a long life of liberty. Captain Leonard “Max” Schroeder, who was born on July 16, 1918, in Linthicum Heights, Maryland, passed away from emphysema early on the morning of May 26, 2009, in Largo, Florida at the age of 90.

government. It was an amazing ceremony to pay homage to his heroic efforts that helped turn the tide for the Allies in World War II. It was an honor he had given no thought to as he looked out at that beach on that long ago June 6, 1944…but, an honor that he had earned along with all the other men who fought, and the many who had died. I’m sure those who gave all, were thankful that some made it home and managed to live a long life of liberty. Captain Leonard “Max” Schroeder, who was born on July 16, 1918, in Linthicum Heights, Maryland, passed away from emphysema early on the morning of May 26, 2009, in Largo, Florida at the age of 90.

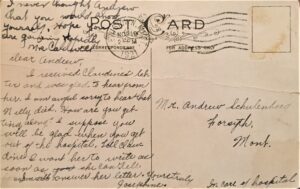

When my husband, Bob’s grandfather, Andy Schulenberg was a boy of 14 years, he was involved in a hunting accident, in which his leg was injured. Things were different in those days, and medicine just wasn’t as advanced as it is now. Not that medicine was antiquated in 1920, but much has been learned about how to save limbs since those days. Grandpa’s leg did not fare well, and after fighting infections, most likely gangrene, and losing the battle, it became apparent that if they were to save his life, they would have to sacrifice the leg.

When my husband, Bob’s grandfather, Andy Schulenberg was a boy of 14 years, he was involved in a hunting accident, in which his leg was injured. Things were different in those days, and medicine just wasn’t as advanced as it is now. Not that medicine was antiquated in 1920, but much has been learned about how to save limbs since those days. Grandpa’s leg did not fare well, and after fighting infections, most likely gangrene, and losing the battle, it became apparent that if they were to save his life, they would have to sacrifice the leg.

Following the accident and with the amputation, Grandpa send 14 months in the hospital. Now that’s a long time for anyone, but for a 14-year-old boy, that must have felt like an eternity. He missed a year of school, as well as all the fun things kids that age were doing. He also missed helping his parents with various chores, something which might not seem to be a negative thing, but when boredom sets in, a person would far rather work on the farm than lay in a bed. While inventors had dabbled

with the invention of the television, it was by no means perfected, and so he basically had the visitors who came in and books for entertainment. Not much fun really, especially since a lot of boys aren’t terribly interested in reading. Thankfully for Grandpa, his family tried to rally around him, and he received a number of postcard letters during that time. I would imagine he lived for the mail delivery, hoping he got a letter, after which he devoured the words on the page, even if the writer didn’t always pick their words very carefully. It was his connection to the outside world.

with the invention of the television, it was by no means perfected, and so he basically had the visitors who came in and books for entertainment. Not much fun really, especially since a lot of boys aren’t terribly interested in reading. Thankfully for Grandpa, his family tried to rally around him, and he received a number of postcard letters during that time. I would imagine he lived for the mail delivery, hoping he got a letter, after which he devoured the words on the page, even if the writer didn’t always pick their words very carefully. It was his connection to the outside world.

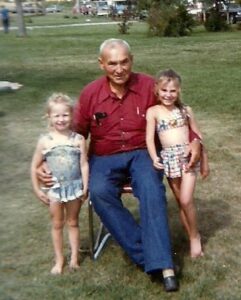

Grandpa was fitted with a wooden peg leg, but it would still be a long road learning to walk with it. I never knew exactly how high the leg went, but I believe it was probably mid-thigh. It was during this time that Grandpa would show his true fortitude He could have laid in that bed, giving up and letting other people take care of him, but he didn’t do that. He got up and worked hard to recover his mobility. Sure, he knew that things would never be the same, but he had things he wanted to do, and he was determined not to let this take him out of commission.

He went on to become the Sheriff of Rosebud County. One might think that he would never want anything to do with guns again, but while he didn’t really see the need for them much as sheriff, he was still well able to use

them. He was sheriff between 1955 and 1972, and during that time, he was well known as “the sheriff without a gun.” It’s hard to imagine a sheriff who has a reputation big enough to be able to work without a gun, including making arrests, but that was what he did. I don’t know if guns bothered him or not, but if so, he was quite successful at hiding it. Today is the 116th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Schulenberg!! We love and miss you very much.

them. He was sheriff between 1955 and 1972, and during that time, he was well known as “the sheriff without a gun.” It’s hard to imagine a sheriff who has a reputation big enough to be able to work without a gun, including making arrests, but that was what he did. I don’t know if guns bothered him or not, but if so, he was quite successful at hiding it. Today is the 116th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Schulenberg!! We love and miss you very much.

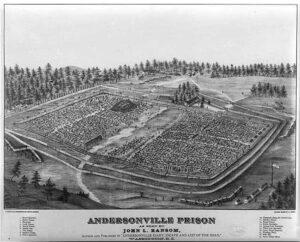

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

According to former prisoner, enlisted soldier John Levi Maile, “It consisted of a narrow strip of board nailed to a row of stakes, about four feet high.” The “dead line” completely encircled Andersonville. Soldiers were told to “shoot any prisoner who touches the ‘dead line'” “It was the standing order to the guards,” Maile explained. “A sick prisoner inadvertently placing his hand on the “dead line” for support… or anyone touching it with suicidal intent, would be instantly shot at, the scattering balls usually striking other than the one aimed at.” It was a risk the prisoners took if they chose to be anywhere near the “dead line” at all. Prisoner Prescott Tracy worked as a clerk in the Andersonville hospital. He said, “I have seen one hundred and fifty bodies waiting passage to the “dead house,” to be buried with those who died in hospital. The average of deaths through the earlier months was thirty a day; at the time I left, the average was over one hundred and thirty, and one day the record showed one hundred and forty-six.” The major threats in the prison camp were diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy.

A sergeant major in the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Robert H. Kellogg what he saw when he entered the camp as a prisoner on May 2, 1864, “As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect…stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.”

After hearing the accounts of men who had the misfortune of being incarcerated in this horrific POW camp, I

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

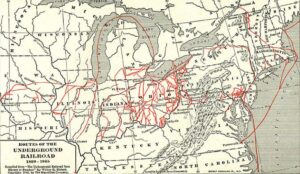

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

In any kind of slavery situation, there are always people who are willing to help those who are being held against their will. Just like during the Holocaust, when the slaves were in trouble, people came to their rescue by forming the Underground Railroad. One hero of the Underground Railroad was Levi Coffin. In the winter of 1826-1827, fugitives began to come show up at the Coffin house. It started out as a well-kept secret and just a few slaves came, but the numbers increased as it became more widely known on different routes. These slaves were running away from bondage, beatings, and limitless working hours. Their lives were little better than death, and they knew they had to escape or die.

When they arrived at the Coffin house, they were welcomed in and given shelter, they would usually sleep during the day, and then they were quickly forwarded safely on their journey. Neighbors who had been too fearful of the penalty of the law to help at first, saw how well the Underground Railroad was being run and soon they felt encouraged to help. A big part of the change of attitude came from the fearless manner in which Levi Coffin acted and the success his efforts produced. The neighbors began to contribute clothing the fugitives and aid in forwarding them on their way. They were still too afraid to shelter them under their own roof, so that part of the work fell to the Coffin household. There were the “content to watch” people, who obviously wanted to see the work go on…as long as someone else took the risk. And of course, there were those who told Levin Coffin he was wasting his time. They tried to discourage him and dissuade him from running such risks, telling him that they were greatly concerned for my safety and monetary interests. They tried to convince him that continuing this risky business could damage his business and possibly even ruin him. The told him he could be  endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

endangering himself and his family too. I suppose it could have, because there are always those who sympathized with the slave-owners, but Levi Coffin could not stand to see the horrible treatment the slaves endured. He had to do something, no matter what it cost him, just like those who helped the Jews during the Holocaust.

Levi listened to these “counselors” and then told them that he “felt no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If, by doing my duty and endeavoring to fulfill the injunctions of the Bible, I injured my business, then let my business go. As to my safety, my life was in the hands of my Divine Master, and I felt that I had his approval. I had no fear of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. If I was faithful to duty and honest and industrious, I felt that I would be preserved and that I could make enough to support my family.”

Even some of those people who were opposed to slavery, felt it was very wrong to harbor fugitive slaves. They figured that the slaves must be guilty of some crime, such as possibly killing their masters or committed some other crime in their escape attempts…making those who helped them an accomplice to the “crime” they were supposedly guilt of. Oh, they had every imaginable objection, and figured it was, at the very least, their duty to make their thoughts known. Once they had voiced their objections, their conscience was clear, and if Levi met with a tragic end, they could at least say, “I told him!!” Levi, in return asked one such “neighbor’s keeper” neighbor, if he thought the Good Samaritan stopped to inquire whether the man who fell among thieves was guilty of any crime before he attempted to help him? He said, “I asked him if he were to see a stranger who had fallen into the ditch would he not help him out until satisfied that he had committed no atrocious deed?” I suppose it was a “crime” to escape their masters, but then some laws should not be laws, and slavery certainly falls into that category. Levi Coffin had to follow his spirit and do what he felt God would expect of him, and in  the end, he saved many lives.

the end, he saved many lives.

Many of Levi’s pro-slavery customers left him for a time, and sales were down. For while his business struggled, but Levi knew that he was doing God’s will, and so God would take care of him and his business. Before long, new customers replaced those who had left him. New settlements were rapidly forming to the north and Levi’s own was filling up with emigrants from North Carolina and other States. His trade increased and his business grew. He says of this time in his life, “I was blessed in all my efforts and succeeded beyond my expectations.”

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

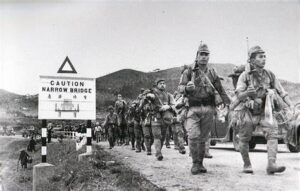

One man, Corporal Ronald Rosser, earned his Medal of Honor while serving in the 38th Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division during the Korean War. Rosser enlisted in Army at the age of 17 and served from 1946 until 1949. His tour was finished, and he went home, but then his younger brother was killed in Korea in February of 1951. Rosser was devastated, but instead of wallowing in grief, he chose to honor his brother. Rosser re-enlisted to “finish his [brother’s] tour” of duty. Revenge was the only thing he could do for his brother now, and Rosser wanted revenge. In January of 1952, Rosser was a part of the regiment’s L Company. L Company was dispatched to capture an enemy-occupied hill. The battle there was fierce and enemy resistance caused heavy casualties. L Company was reduced to just 35 men from the initial 170 sent out, but they were ordered to make one more  attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

The envoys’ message was simple: “The British garrison there should simply surrender to the Japanese—resistance was futile.” The envoys were sent home with the following retort: “The governor and commander in chief of Hong Kong declines absolutely to enter into negotiations for the surrender of Hong Kong…”

The unsuccessful negotiations brought a swift wave of Japanese troops, who in retaliation for the refused surrender, landed in Hong Kong with artillery fire for cover and the following order from their commander: “Take no prisoners.” The troops quickly overran a volunteer antiaircraft battery, and the Japanese invaders roped together the captured soldiers. In a complete disregard for human life, a complete disregard for the Geneva Convention rules, or any rules of common decency, the Japanese proceeded to bayonet them to death. Even those who offered no  resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

On that same day, the War Powers Act was passed by Congress, authorizing the president to initiate and terminate defense contracts, reconfigure government agencies for wartime priorities, and regulate the freezing of foreign assets. It also permitted him to censor all communications coming in and leaving the country. President Franklin D Roosevelt appointed the executive news director of the Associated Press, Byron Price, as director of censorship. Although invested with the awesome power to restrict and withhold news, Price took no extreme measures, allowing news outlets and radio stations to self-censor, which they did. Most top-secret information, including the construction of the atom  bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

“The most extreme use of the censorship law seems to have been the restriction of the free flow of “girlie” magazines to servicemen…including Esquire, which the Post Office considered obscene for its occasional saucy cartoons and pinups. Esquire took the Post Office to court, and after three years the Supreme Court ultimately sided with the magazine.” It amazes me just how much times have changed. These days the “girlie” trash is totally acceptable, but truth is censored and lies are allowed. Too bad we are so far out from those days.

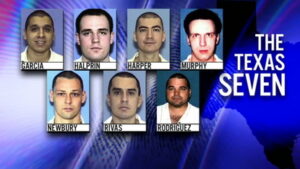

Maybe they were just wanting to be home for Christmas, and not knowing exactly how long it would take…while hiding out from the law, that is…the Texas Seven decided to get a jump start on the journey. No, probably not. It wasn’t Christmas with loved ones that was on their minds…it was freedom. On December 13, 2000, seven prisoners dubbed the “Texas Seven” by the media, broke out of maximum-security prison in South Texas, setting off a massive six-week manhunt. The prisoners were Joseph Christopher Garcia, Randy Ethan Halprin, Larry James Harper, Patrick Henry Murphy Jr, Donald Keith Newbury, George Angel Rivas Jr, and Michael Anthony Rodriguez. The escapees overpowered civilian employees and prison guards in the maintenance shop where they worked and stole clothing, guns, and a vehicle. The men left a note saying: “You haven’t heard the last of us yet,” and they were right. These men were convicted of crimes like murder, rape, and robbery. They were set to be executed soon, so they had nothing to lose.

Maybe they were just wanting to be home for Christmas, and not knowing exactly how long it would take…while hiding out from the law, that is…the Texas Seven decided to get a jump start on the journey. No, probably not. It wasn’t Christmas with loved ones that was on their minds…it was freedom. On December 13, 2000, seven prisoners dubbed the “Texas Seven” by the media, broke out of maximum-security prison in South Texas, setting off a massive six-week manhunt. The prisoners were Joseph Christopher Garcia, Randy Ethan Halprin, Larry James Harper, Patrick Henry Murphy Jr, Donald Keith Newbury, George Angel Rivas Jr, and Michael Anthony Rodriguez. The escapees overpowered civilian employees and prison guards in the maintenance shop where they worked and stole clothing, guns, and a vehicle. The men left a note saying: “You haven’t heard the last of us yet,” and they were right. These men were convicted of crimes like murder, rape, and robbery. They were set to be executed soon, so they had nothing to lose.

These were not the kind of people that anyone wanted to have running around the state…or anywhere outside of prison walls. Soon after escaping from the Connally Unit lockup in Kenedy, Texas, the fugitives picked up another getaway vehicle. This one provided by the father of one of the men. They robbed a Radio Shack store in Pearland, Texas, coming out with cash and police scanners. On Christmas Eve, the escapees struck a sporting-goods store in Irving, Texas, where they stole a large amount of cash and weapons. In the process, the men killed police officer Aubrey Hawkins, shooting him multiple times with multiple weapons and running him over. Now they really had nothing to lose. Now, they were cop killers on top of everything else. It looked like it was time to get out of Dodge…or in this case, Texas.

The Texas Seven headed to Colorado, where they purchased a motor home and told people they were Christian missionaries. They rented a spot at a trailer park near Woodland Park, Colorado. They were there about a month before things started to fall apart. On January 22, 2001, after seeing the “Texas Seven” profiled on the TV program America’s Most Wanted, someone tipped off the police to the group of seven “missionaries” near Woodland Park. During the raid, ringleader George Rivas was captured along with three of the other men. Larry James Harper decided that he was not going back to prison, so he committed suicide after being surrounded by  police. Two days later, law enforcement officials closed in on the two remaining escapees at a hotel in Colorado Springs. A standoff ensued, during which the fugitives conducted phone interviews with a TV news station and claimed their escape was a protest against Texas’ criminal justice system. Someone always has to add a bit of drama to justify their new crimes. There was no evidence indicating their claim was justified. The men then surrendered to authorities. Their crime spree was over. Of the six remaining, four have since been executed. Randy Ethan Halprin and Patrick Henry Murphy Jr are currently back at Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas on Death Row awaiting execution.

police. Two days later, law enforcement officials closed in on the two remaining escapees at a hotel in Colorado Springs. A standoff ensued, during which the fugitives conducted phone interviews with a TV news station and claimed their escape was a protest against Texas’ criminal justice system. Someone always has to add a bit of drama to justify their new crimes. There was no evidence indicating their claim was justified. The men then surrendered to authorities. Their crime spree was over. Of the six remaining, four have since been executed. Randy Ethan Halprin and Patrick Henry Murphy Jr are currently back at Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas on Death Row awaiting execution.

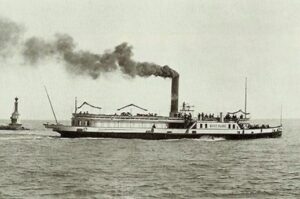

Disaster was eminent that December 6, 1917, and indeed, the disaster had already begun, but it was very likely to get far worse. Vincent Coleman and his co-worker, Chief Clerk William Lovett were working at the Richmond station where they received word that there was a crash between the French munitions ship, SS Mont-Blanc, and a Norwegian ship, SS Imo. A collision, in and of itself, would not have been any more serious than any other collision, except that the French munitions ship, was carrying a deadly cargo of high explosives. The likelihood of an explosion was the eminent disaster that was waiting to happen.

Disaster was eminent that December 6, 1917, and indeed, the disaster had already begun, but it was very likely to get far worse. Vincent Coleman and his co-worker, Chief Clerk William Lovett were working at the Richmond station where they received word that there was a crash between the French munitions ship, SS Mont-Blanc, and a Norwegian ship, SS Imo. A collision, in and of itself, would not have been any more serious than any other collision, except that the French munitions ship, was carrying a deadly cargo of high explosives. The likelihood of an explosion was the eminent disaster that was waiting to happen.

That day, in what was called the Halifax Explosion, Coleman is remembered as one of the heroic figures, because of his quick-thinking message to an oncoming train to stop and remain out of range before the explosion. Coleman knew what was coming, and he saved many lives as a result of holding back that train. born on March 13th, 1872, was a train dispatcher for the Canadian Government  Railways. Moments after the collision, the SS Mont-Blanc caught fire and the crew abandoned the ship. Now it was up to Vincent, trying to hold back a sense of panic, to figure out what trains were going to be coming into Halifax. He knew they had to be warned.

Railways. Moments after the collision, the SS Mont-Blanc caught fire and the crew abandoned the ship. Now it was up to Vincent, trying to hold back a sense of panic, to figure out what trains were going to be coming into Halifax. He knew they had to be warned.

Part of the reason for such a panicked state was that the French ship had drifted from the middle of the channel to the pier. While still burning, she beached herself on the shore in a matter of minutes. The captain warned Coleman of the deadly cargo on the ship, and Coleman flew into action. He immediately sent a telegraph to the Number 10 overnight express train that was coming in from Saint John, New Brunswick, carrying over 300 passengers, telling them to stop where they were and remain there until further notice, thereby saving the lives of passengers and crew. Then, Lovett and Coleman quickly evacuated their station, but Coleman couldn’t stay  away. There was too much danger. Coleman returned to the station and continued to warn trains all the way to Truro in order to stop them from any closer to the scene. Coleman’s morse was code message was this: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” While Coleman’s message stopped the Number 10 train, saving the lives of 300 people, and also likely saved other lives with his warnings to stay back, he lost his own life in the endeavor when the ship exploded. Staying at the station was a courageous act that cost Coleman his life.

away. There was too much danger. Coleman returned to the station and continued to warn trains all the way to Truro in order to stop them from any closer to the scene. Coleman’s morse was code message was this: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” While Coleman’s message stopped the Number 10 train, saving the lives of 300 people, and also likely saved other lives with his warnings to stay back, he lost his own life in the endeavor when the ship exploded. Staying at the station was a courageous act that cost Coleman his life.