History

Salar de Uyuni (or Salar de Tunupa) is not a place that most of us living in the United States would have heard of, unless we are a world traveler or an avid travel reader, that is. Salar de Uyuni is the world’s largest salt flat, or playa, at over 3,900 square miles in area. A playa is defined as a the flat-floored bottom of an undrained desert basin that becomes at times a shallow lake. Salar de Uyuni is in the Daniel Campos Province in Potosí in southwest Bolivia, probable the main reason we may not have heard of it before. Salar is near the crest of the Andes at an elevation of 11,995 feet above sea level.

Salar de Uyuni (or Salar de Tunupa) is not a place that most of us living in the United States would have heard of, unless we are a world traveler or an avid travel reader, that is. Salar de Uyuni is the world’s largest salt flat, or playa, at over 3,900 square miles in area. A playa is defined as a the flat-floored bottom of an undrained desert basin that becomes at times a shallow lake. Salar de Uyuni is in the Daniel Campos Province in Potosí in southwest Bolivia, probable the main reason we may not have heard of it before. Salar is near the crest of the Andes at an elevation of 11,995 feet above sea level.

The Salar de Uyuni is a strange, sometimes lake/sometimes desert that was formed as a result of transformations between several prehistoric lakes that existed around forty thousand years ago, but had all evaporated over time. The area has a large salt content, creating a flat that is now  covered by a few meters of salt crust. The area is amazingly flat with the average elevation variations within one meter over the entire area of the Salar. The crust serves as a source of salt and covers a pool of brine, which is exceptionally rich in lithium. The large area, clear skies, and exceptional flatness of the surface make the Salar de Uyuni ideal for calibrating the altimeters of Earth observation satellites. After it rains in the area, a thin layer of dead calm water transforms the flat into the world’s largest mirror, 80 miles across. Many people have photographed its amazing picturesque views.

covered by a few meters of salt crust. The area is amazingly flat with the average elevation variations within one meter over the entire area of the Salar. The crust serves as a source of salt and covers a pool of brine, which is exceptionally rich in lithium. The large area, clear skies, and exceptional flatness of the surface make the Salar de Uyuni ideal for calibrating the altimeters of Earth observation satellites. After it rains in the area, a thin layer of dead calm water transforms the flat into the world’s largest mirror, 80 miles across. Many people have photographed its amazing picturesque views.

The Salar is a prime breeding ground for several species of Flamingos, and also serves as the major transport route across the Bolivian Altiplano. Salar de Uyuni is also a climatological transitional zone since the towering tropical cumulus congestus and cumulonimbus incus clouds that form in the eastern part of the salt flat during the summer cannot permeate beyond its drier western edges, near the Chilean border and the Atacama Desert.  During the dry season, the water on the playa dries up, and forms crystalline formations as the salt dries out. During the wet season it becomes a shallow lake that reflects the sky beautifully.

During the dry season, the water on the playa dries up, and forms crystalline formations as the salt dries out. During the wet season it becomes a shallow lake that reflects the sky beautifully.

“Salar means salt flat in Spanish. Uyuni originates from the Aymara language and means a pen (enclosure); Uyuni is a surname and the name of a town that serves as a gateway for tourists visiting the Salar. Thus Salar de Uyuni can be loosely translated as a salt flat with enclosures, the latter possibly referring to the “islands” of the Salar; or as “salt-flat at Uyuni (the town named ‘pen for animals’)”.

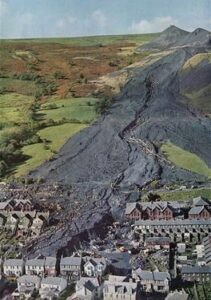

On the morning of October 21, 1966, a catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip occurred on a mountain slope above the Welsh village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil. A spoil tip, also called a boney pile, culm bank, gob pile, waste tip, or…in Scotland, bing, is a pile built of accumulated spoil…waste material removed during mining. These waste materials are typically composed of shale, but they also contain smaller quantities of carboniferous sandstone and other residues. Spoil tips are not formed of slag, but in some areas, such as England and Wales, they are referred to as slag heaps. The area near Aberfan overlaid a natural spring, and a period of heavy rain led to a build-up of water within the tip which caused it to suddenly slide downhill as a slurry. The disaster killed 116 children and 28 adults, as it engulfed Pantglas Junior School and a row of houses. The accident left just five survivors and wiped out half the town’s youth. The Aberfan disaster became one of the United Kingdom’s worst coal mining accidents, but strangely it isn’t anything like a normal coal mining accident.

On the morning of October 21, 1966, a catastrophic collapse of a colliery spoil tip occurred on a mountain slope above the Welsh village of Aberfan, near Merthyr Tydfil. A spoil tip, also called a boney pile, culm bank, gob pile, waste tip, or…in Scotland, bing, is a pile built of accumulated spoil…waste material removed during mining. These waste materials are typically composed of shale, but they also contain smaller quantities of carboniferous sandstone and other residues. Spoil tips are not formed of slag, but in some areas, such as England and Wales, they are referred to as slag heaps. The area near Aberfan overlaid a natural spring, and a period of heavy rain led to a build-up of water within the tip which caused it to suddenly slide downhill as a slurry. The disaster killed 116 children and 28 adults, as it engulfed Pantglas Junior School and a row of houses. The accident left just five survivors and wiped out half the town’s youth. The Aberfan disaster became one of the United Kingdom’s worst coal mining accidents, but strangely it isn’t anything like a normal coal mining accident.

The colliery spoil tip was the responsibility of the National Coal Board (NCB), and the inquiry into the disaster placed the blame on the organization, also naming nine employees. When everything broke loose, the resulting landslide sent 140,000 cubic yards of coal waste in a tidal wave 40-feet high hurtling  down the mountainside where Merthyr Vale Colliery stood. The slide destroyed farmhouses, cottages, houses, and part of the neighboring County Secondary School. The avalanche is thought to have been the result of shoddy construction and a build-up of water in one of the colliery’s spoil tips…piles of waste material removed during mining.

down the mountainside where Merthyr Vale Colliery stood. The slide destroyed farmhouses, cottages, houses, and part of the neighboring County Secondary School. The avalanche is thought to have been the result of shoddy construction and a build-up of water in one of the colliery’s spoil tips…piles of waste material removed during mining.

Like many countries and areas, Wales was known for coal mining during the Industrial Revolution. Aberfan’s colliery opened in 1869. It didn’t take long for it to run out of space for waste, and by 1916 the space on the mountain valley floor was full. At that point, the colliery started “tipping” on the mountainside above the town. In 1966 it amassed seven tips containing 2.7 million cubic yards of colliery spoil.

Aberfan’s town council had contacted the National Coal Board to express concerns over the spoil tips years  before the incident, following a non-lethal accident on the colliery. Unfortunately, they took no action at that time, and the issue was never addressed. The tip that fell on October 21 covered material that previously slipped. The disaster received widespread national attention. Queen Elizabeth II did not visit the site until eight days after the accident, and she admitted later that not going sooner was one of her biggest regrets. Once the disaster happened, little can be done to fix the matter, but the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act was passed in 1969 to add provisions when using mining tips, among other things. Sadly it was too late for those lost, but it was good news for future miners and the surrounding towns.

before the incident, following a non-lethal accident on the colliery. Unfortunately, they took no action at that time, and the issue was never addressed. The tip that fell on October 21 covered material that previously slipped. The disaster received widespread national attention. Queen Elizabeth II did not visit the site until eight days after the accident, and she admitted later that not going sooner was one of her biggest regrets. Once the disaster happened, little can be done to fix the matter, but the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act was passed in 1969 to add provisions when using mining tips, among other things. Sadly it was too late for those lost, but it was good news for future miners and the surrounding towns.

When a ship sinks, we expect to be able to find it, or at least find out where it went down. With radios, making it possible to receive a “May Day” call, we expect to be able to pinpoint the location of the floundering ship. Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes, no matter how hard we search for the ship, plane, and even car, but the search seems to be in vain. I think it is more common to have a search without success when it comes to a ship or even a plane in the ocean. It is so hard to see something that is so far below the surface. Still, it seems like after a century or more, there should be some breakthrough…shouldn’t there.

When a ship sinks, we expect to be able to find it, or at least find out where it went down. With radios, making it possible to receive a “May Day” call, we expect to be able to pinpoint the location of the floundering ship. Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes, no matter how hard we search for the ship, plane, and even car, but the search seems to be in vain. I think it is more common to have a search without success when it comes to a ship or even a plane in the ocean. It is so hard to see something that is so far below the surface. Still, it seems like after a century or more, there should be some breakthrough…shouldn’t there.

A 550-foot-long naval ship, USS Cyclops debuted in 1910. The ship was a bit of a jack-of-all-trades, so to speak…at least in it’s early days. It moved coal around the seas, as well as providing aid to refugees. Then, during World War I, USS Cyclops became a naval transporter. In 1918, the Cyclops, with it’s crew of 306 people and 11,000 tons of manganese, sailed from Brazil. The ship made a stop in Barbados and then sailed on toward Baltimore. Somewhere along the way, it disappeared. Strangely, there was no SOS made. It was as if the ocean had swallowed the ship up. Now one knew exactly where to look for it, because it had sailed quite a ways from its last known location. Maybe if there had been a distress call of any kind, they could have had a general location. Without that, they didn’t know if it had gone off course, or how fast it was traveling, so there was no way to be sure. It was thought that the Cyclops may have gone down in  the Puerto Rico Trench. The waters there run very deep, which would have made it very difficult to located the ship in 1918. Still, there was another hazardous area…the Bermuda Triangle, and some people thought that might be to blame.

the Puerto Rico Trench. The waters there run very deep, which would have made it very difficult to located the ship in 1918. Still, there was another hazardous area…the Bermuda Triangle, and some people thought that might be to blame.

The US Navy calls the tragedy of Cyclops, “The disappearance of this ship has been one of the most baffling mysteries in the annals of the Navy. All attempts to locate her have proved unsuccessful.” To this day, the original Cyclops has never been found. Many other ships that were lost at sea have been found, many that were lost before Cyclops, but there has been no sign of Cyclops. The mystery of Cyclops might never be solved, and considering the lives lost, that is very sad indeed.

I have lived in Wyoming since I was three years old, and so sometimes it’s easy for me to forget some of the places that have great historical value, but they are not as well known as some of the other places, like Yellowstone National Park. Register Cliff is one such landmark that I don’t often think about, although I have been there, and it really is a cool place.

I have lived in Wyoming since I was three years old, and so sometimes it’s easy for me to forget some of the places that have great historical value, but they are not as well known as some of the other places, like Yellowstone National Park. Register Cliff is one such landmark that I don’t often think about, although I have been there, and it really is a cool place.

Register Cliff is a sandstone cliff, that is located on the Oregon Trail. The cliff is a soft, chalky, limestone wall rising more than 100 feet above the North Platte River. When my sisters and I were kids, our parents would take us on trips, and point out every (and I mean every) Oregon Trail marker that we passed. In Wyoming, that is a lot of markers. As the emigrants made their way on the Oregon Trail, searching for a better life in the west, they came upon this cliff and chiseled the names of their families on the soft stones of the cliff. It was one of the key checkpoint landmarks for parties heading west along the Platte River valley west of Fort John, Wyoming which allowed  travelers to verify they were on the correct path up to South Pass and not moving into impassable mountain terrains. Geographically, it is on the eastern ascent of the Continental divide leading upward out of the great plains in the eastern part of Wyoming.

travelers to verify they were on the correct path up to South Pass and not moving into impassable mountain terrains. Geographically, it is on the eastern ascent of the Continental divide leading upward out of the great plains in the eastern part of Wyoming.

As more and more people “registered” on the cliff, word started to get around about this notable historic landmark. People quickly began to see the value of the cliff. Besides knowing that they were going the right direction, the emigrants realized that they were a part of history. Their names would forever be carved in the stone of the cliff, stating that they were among the brave people who moved to the west to settle the land.

The practice soon became the custom of the day, and the other northern Emigrant Trails that split off farther west such as the California Trail and Mormon Trail began to follow the custom too, inscribing their names on its  rocks during the western migrations of the 19th century. It is estimated that 500,000 emigrants used these trails from 1843–1869. Unfortunately, up to one-tenth of the emigrants died along the way, usually due to disease and other hazards. Nevertheless, those who made it this far were forever known to those who stop by. Register Cliff is the easternmost of the three prominent emigrant “recording areas” located within Wyoming. The other two are Independence Rock and Names Hill. The site was where emigrants camped on their first night west of Fort Laramie. The property was donated by Henry Frederick to the state of Wyoming, to be preserved. Register Cliff was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

rocks during the western migrations of the 19th century. It is estimated that 500,000 emigrants used these trails from 1843–1869. Unfortunately, up to one-tenth of the emigrants died along the way, usually due to disease and other hazards. Nevertheless, those who made it this far were forever known to those who stop by. Register Cliff is the easternmost of the three prominent emigrant “recording areas” located within Wyoming. The other two are Independence Rock and Names Hill. The site was where emigrants camped on their first night west of Fort Laramie. The property was donated by Henry Frederick to the state of Wyoming, to be preserved. Register Cliff was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

As you know, war is a tough time to be on a ship. There is no guarantee that the ship will make it through the war, and if a ship goes down in a battle, it usually takes some, if not all of the crew with it. A cat would usually have little chance of survival on a ship that is sinking, but someone forgot to tell Oskar that. Oskar was a black and white patched cat. It is thought that he was originally owned by one of the crewman of the German battleship Bismarck and was on board the ship on May 18, 1941 when the ship set sail on Operation Rheinübung (German for Rhine Exercise). It was the Bismarck’s only mission. On May 27, 1941, the Bismarck was sunk after a fierce sea-battle. The sinking took with it most of the crew. Out of a crew of 2,100 men, only 115 from her crew survived…and one cat. Hours after the sinking, Oscar was found floating on a board and picked from the water by the British destroyer HMS Cossack.

The crew of the Cossack decided that since Oscar was used to being on a ship, he could just stay with them. So, Oscar “served” on board Cossack for the next few months as the ship carried out convoy escort duties in the Mediterranean Sea and north Atlantic Ocean. On October 24, 1941, Cossack was escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to Great Britain when she was severely damaged by a torpedo fired by the German submarine U-563. The surviving crew were transferred to the destroyer HMS Legion, and an attempt was made to tow the badly listing Cossack back to Gibraltar. Unfortunately, the weather was not cooperative, and as it worsened, the task became impossible and had to be abandoned. On October 27, a day after the tow was slipped, Cossack sank to the west of Gibraltar. The initial explosion had blown off one third of the forward section of the ship, killing 159 of the crew, but Oscar survived, and was taken to Gibraltar. To say that a cat has nine lives is almost an understatement when it came to Oscar.

Following the sinking of Cossack, Oscar was given the nickname “Unsinkable Sam” and was soon transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, which by coincidence was instrumental in the destruction of Bismarck, along with Cossack. This assignment was not going to prove safer for Sam, and one might begin to wonder if he should be given another shore assignment…for the sake of the ships. When the Ark Royal was returning from Malta on November 14, 1941, it too was torpedoed, this time by U-81. Again they attempted to tow Ark Royal to Gibraltar, but they were unable to stop the inflow of water, so the attempt was futile. The carrier rolled over and sank 30 miles from Gibraltar. The good news was that due to the slow rate of the sinking, all but one crew member were able to be evacuated, along with, of course, Unsinkable Sam. The survivors, including Sam, who had been found clinging to a floating plank by a Motor Launch and described as “angry but quite unharmed,” were transferred to HMS Lightning and the same HMS Legion which had also rescued the crew of Cossack. Legion would itself be sunk in 1942, and Lightning in 1943. The life of a ship in wartime was not a safe one.

After the third ship sank under Sam’s paws, it was decided that maybe he shouldn’t be on a ship, so he was transferred first to the offices of the Governor of Gibraltar and then sent back to the United Kingdom, where he saw out the remainder of the war living in a seaman’s home in Belfast called the “Home for Sailors.” I think Sam had earned his place there. Sam died in 1955. A pastel portrait of Sam, which was titled “Oscar, the Bismarck’s Cat” by the artist Georgina Shaw-Baker is on display in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Of course, as with all war stories, some authorities question whether Oskar/Sam’s biography might be a “sea story,” because for example, there are pictures of two different cats identified as Oskar/Sam. It is my opinion that whether it is true or not, it lends a lighthearted note to the otherwise tragic stories of war, and therefore, I choose to believe it is true.

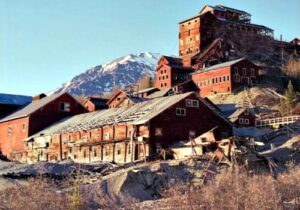

When the minerals in a mine run out, or become less valuable, the mine tends to close down. These days, they try to return the mine to it’s prior state, but then many mines these days are pit mines, or strip mines. I suppose it is easier to return them to their prior state when you only have to fill in the hole, and I’m not opposed to that process. It can make a beautiful place out of ground that has been ripped apart. In some cases, it looks better after the reclamation.

When the minerals in a mine run out, or become less valuable, the mine tends to close down. These days, they try to return the mine to it’s prior state, but then many mines these days are pit mines, or strip mines. I suppose it is easier to return them to their prior state when you only have to fill in the hole, and I’m not opposed to that process. It can make a beautiful place out of ground that has been ripped apart. In some cases, it looks better after the reclamation.

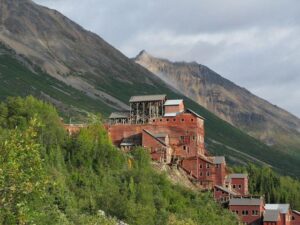

The Kennecott Mine, often spelled Kennicott, is an abandoned mining camp in the Valdez-Cordova Census Area, which is now the Copper River Census Area in the state of Alaska. The mine was, at one time, the center of activity for several copper mines. Kennecott Mines was named after the Kennicott Glacier in the valley below. The geologist Oscar Rohn named the glacier after Robert Kennicott during the 1899 US Army Abercrombie Survey. A “clerical error” resulted in the substitution of an “e” for the “i,” supposedly by Stephen Birch himself. The mine is located northeast of Valdez, inside Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve. The camp and mines are now a National Historic Landmark District administered by the National Park Service. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986. It’s status as a historical site, probably explains the good shape it is in. Many historical sites deteriorate badly before anyone realizes that they should be preserved as a part of history.

Two prospectors, “Tarantula” Jack Smith and Clarence L Warner, who were with a group of prospectors associated with the McClellan party in the summer of 1900, spotted “a green patch far above them in an  improbable location for a grass-green meadow.” Upon inspection, the green turned out to be malachite, located with chalcocite…aka “copper glance,” and the location of the Bonanza claim. A few days later, Arthur Coe Spencer, US Geological Survey geologist also found chalcocite at the same location. It was the birth of a copper mine.

improbable location for a grass-green meadow.” Upon inspection, the green turned out to be malachite, located with chalcocite…aka “copper glance,” and the location of the Bonanza claim. A few days later, Arthur Coe Spencer, US Geological Survey geologist also found chalcocite at the same location. It was the birth of a copper mine.

A mining engineer just out of school, named Stephen Birch was in Alaska looking for investment opportunities in minerals. He was young, but he came with the financial backing of the Havemeyer Family and another investor named James Ralph, from his days in New York. Birch spent the winter of 1901-1902 acquiring the “McClellan group’s interests” for the Alaska Copper Company of Birch, Havemeyer, Ralph and Schultz, later to become the Alaska Copper and Coal Company. He spent the summer of 1901, visiting the property and “spent months mapping and sampling.” He confirmed the Bonanza mine and surrounding deposits, were at the time, the richest known concentration of copper in the world.

Kennecott had five mines: Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode, Erie, and Glacier. “Glacier, which is really an ore extension of the Bonanza, was an open-pit mine and was only mined during the summer. Bonanza and Jumbo were on Bonanza Ridge about 3 miles from Kennecott. The Mother Lode mine was located on the east side of the ridge from Kennecott. The Bonanza, Jumbo, Mother Lode and Erie mines were connected by tunnels. The Erie mine was perched on the northwest end of Bonanza Ridge overlooking Root Glacier about 3.7 miles up a glacial trail from Kennecott.” The copper ore was transported to Kennecott by way of the trams which head-ended at Bonanza and Jumbo. From Kennecott the ore was hauled mostly in 140-pound sacks on steel flat cars  to Cordova, 196 rail miles away on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CRNW).

to Cordova, 196 rail miles away on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CRNW).

In 1925 a Kennecott geologist predicted that the end of the high-grade ore bodies was in sight. The mines days were numbered. The highest grades of ore were largely depleted by the early 1930s. The Glacier Mine closed in 1929, and the rest followed soon after. The last train left Kennecott on November 10, 1938. It was now a ghost town. Over a period of 20 years the population dropped from 494 in 1920 to 5 in 1940. Thankfully the historical value of this particular site was not lost, and is still there today.

When I think of a hurricane, I think of a tropical storm that escalates, and I suppose most of the time, that would be right, but it isn’t always the case. Sometimes hurricanes can develop in a more northern area, or as in the case of Hurricane Hazel on October 15, 1954 a strong hurricane somehow continues north as a hurricane after it hit first in a more southern area. Hurricane Hazel was a hurricane that struck the Carolina’s, and then and then moved into Ontario as a powerful extratropical storm…still of hurricane intensity, after that initial strike in the Carolinas.

When I think of a hurricane, I think of a tropical storm that escalates, and I suppose most of the time, that would be right, but it isn’t always the case. Sometimes hurricanes can develop in a more northern area, or as in the case of Hurricane Hazel on October 15, 1954 a strong hurricane somehow continues north as a hurricane after it hit first in a more southern area. Hurricane Hazel was a hurricane that struck the Carolina’s, and then and then moved into Ontario as a powerful extratropical storm…still of hurricane intensity, after that initial strike in the Carolinas.

The deadliest hurricane of the 1954 Atlantic hurricane season, Hurricane Hazel was also the second costliest, and the most intense hurricane of that year. The storm killed at least 469 people in Haiti before striking the United States as a Category 4 hurricane near the border between North and South Carolina. As Hazel ripped through Haiti, it destroyed 40% of the coffee trees and 50% of the cacao crop, which would drastically affected the economy for several years.

After causing 95 fatalities in the US, Hazel struck Canada as an extratropical storm, raising the death toll by 81 people, mostly in Toronto. When Hazel made landfall near Calabash, North Carolina, it destroyed most waterfront homes. Then as it screamed north along the Atlantic coast, Hazel affected Virginia, Washington DC, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York; as it lashed the area with gusts near 100 miles per hour and caused $281 million, which today would be $2720 million in damage. When it was over Pennsylvania, Hazel consolidated with a cold front and turned northwest towards Canada.

In addition to the fatalities, Hurricane Hazel brought with it flash flooding in Canada, which destroyed twenty bridges, killed 81 people, and left over 2,000 families homeless in Canada alone. In all, and including the strike in the Carolinas, where Hazel killed 95 people and caused almost $630 million ($6,100 million today) in damages, on top of over 500 other deaths and billions in damage in the US and Caribbean. No other recent natural disaster on Canadian soil has been so deadly. Floods killed 35 people on a single street in Toronto.

When it hit Ontario as an extratropical storm, rivers and streams in and around Toronto overflowed their banks, which caused severe flooding. As a result, many residential areas in the local floodplains, such as the Raymore Drive area, were subsequently converted to parkland. In Canada alone, over C$135 million (C$1.3 billion, 2021) of damage was incurred. The effects of Hazel were particularly unprecedented in Toronto due to a combination of heavy rainfall during the preceding weeks, a lack of experience in dealing with tropical storms,

and the storm’s unexpected retention of power despite traveling 680 miles over land. The storm stalled over the Toronto area, and although it was now extratropical, it remained as powerful as a category 1 hurricane. To help with the cleanup, 800 members of the military were called in and a Hurricane Relief Fund was quickly established that distributed $5.1 million ($49.1 million today) in aid. The name Hazel was retired as a named storm, because of the high death toll.

and the storm’s unexpected retention of power despite traveling 680 miles over land. The storm stalled over the Toronto area, and although it was now extratropical, it remained as powerful as a category 1 hurricane. To help with the cleanup, 800 members of the military were called in and a Hurricane Relief Fund was quickly established that distributed $5.1 million ($49.1 million today) in aid. The name Hazel was retired as a named storm, because of the high death toll.

We don’t often think of the United States having castles, but some do exist. Most are not considered true castles, but are rather country houses, follies, or other types of buildings built to give the appearance of a castle. In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings. Castles seem like almost ancient history items to most of us, and when it came to the United States, many people thought of the Old West and homestead type dwellings. Nevertheless, there are a few real castles here in the United States, even if we don’t have royalty here.

We don’t often think of the United States having castles, but some do exist. Most are not considered true castles, but are rather country houses, follies, or other types of buildings built to give the appearance of a castle. In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings. Castles seem like almost ancient history items to most of us, and when it came to the United States, many people thought of the Old West and homestead type dwellings. Nevertheless, there are a few real castles here in the United States, even if we don’t have royalty here.

One such castle is Bannerman Castle in New York. The castle is located on Pollepel Island, about 50 miles north of New York City, on the Hudson River. The castle is in serious disrepair, but the Bannerman Castle Trust, Inc is trying to shore up the buildings so they don’t deteriorate further. The analysis that has been done indicates that 5 out of the 7 buildings on the island could be shored up. The others are too far gone. The castle has a strange history, and I suppose some would debate it’s claim as a true castle. The castle was built by Frank Bannerman VI over a period of 17 years. The island’s buildings were personally designed by Bannerman without professional help from architects, engineers, or contractors. The island has buildings, docks, turrets, garden walls, and a moat in the style of old Scottish castles. That was his passion. He loved Scottish castles and built his castle with a Scottish flare. All of the buildings are elaborately decorated, from biblical quotations cast into all fireplace mantles, to a shield between the towers with a coat of arms, and a wreath of thistle leaves and flowers.

Bannerman’s family immigrated to America in 1854, when he was three. They settled in Brooklyn, New York, where his father established a business selling flags, rope, and other articles acquired at Navy auctions. He was a patriotic man, who joined the union army during the Civil War. At that time young Frank began running the business. He was 13 years old. When the Civil War ended, the US government auctioned off military goods by the ton, mostly to be scrapped for their metal. It was young Frank who saw the importance of these materials, and it was his wise purchases that earned him the moniker “Father of the Army-Navy Store.” He could see that much of what was being sold had a market value higher than scrap. Under the guidance of the younger Bannerman, the Bannerman family became the world’s largest buyer of surplus military equipment. By this time, their storeroom and showroom took up a full block at 501 Broadway. Bannerman made his store into a type of museum/store. It opened to the public in 1905. Of it, the New York Herald said, “No museum in the world exceeds it in the number of exhibits.”

Frank was very prosperous, and it was during a business trip to Ireland that he met his future wife, Helen Boyce. They had three children. At the close of the Spanish American War, Frank Bannerman purchased 90

percent of all captured goods in a sealed bid. After that, it became necessary to find a secure place to store their large quantity of very volatile black powder. His son, David saw Pollepel Island, in the Hudson, and Frank Bannerman purchased it in 1900. Following the purchase, the building of the castle began. Today, the island is owned by the state of New York, and at this time visits are prohibited until the buildings can be made safer.

percent of all captured goods in a sealed bid. After that, it became necessary to find a secure place to store their large quantity of very volatile black powder. His son, David saw Pollepel Island, in the Hudson, and Frank Bannerman purchased it in 1900. Following the purchase, the building of the castle began. Today, the island is owned by the state of New York, and at this time visits are prohibited until the buildings can be made safer.

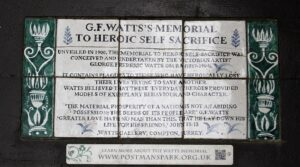

When someone sacrifices their life to save the life of another, its big news for a while, but eventually only the one who was saved, and maybe their family, remember the name of that selfless hero. In 1887, sculptor, George Frederic Watts, who thought that loss of memory concerning these heroes was horribly sad and just plain wrong, proposed a memorial to honor these forgotten heroes.

When someone sacrifices their life to save the life of another, its big news for a while, but eventually only the one who was saved, and maybe their family, remember the name of that selfless hero. In 1887, sculptor, George Frederic Watts, who thought that loss of memory concerning these heroes was horribly sad and just plain wrong, proposed a memorial to honor these forgotten heroes.

The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice is a public monument in Postman’s Park in the City of London. Watts wanted the memorial to be ready in time to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. Unfortunately, the project was not accepted at that time, but in 1898 Watts was approached by Henry Gamble, vicar of Saint Botolph’s Aldersgate church. Postman’s Park was built on the church’s former churchyard, and the church was trying to raise funds to secure its future. That was when Gamble heard about the memorial project inspired by Watts. Gamble felt that Watts’ proposed memorial would raise the profile of the park…make it more memorable. Because it was going to be an ever-evolving memorial, it was unveiled in an unfinished state in 1900. The memorial consisted of a 50-foot wooden loggia designed by Ernest George. A loggia is an  architectural feature which is a covered exterior gallery or corridor usually on an upper level, or sometimes ground level. The loggia sheltered a wall with space for 120 ceramic memorial tiles to be designed and made by William De Morgan. At the unveiling, only four of the memorial tiles were in place.

architectural feature which is a covered exterior gallery or corridor usually on an upper level, or sometimes ground level. The loggia sheltered a wall with space for 120 ceramic memorial tiles to be designed and made by William De Morgan. At the unveiling, only four of the memorial tiles were in place.

Watts died in 1904, before his idea was really in it’s full glory. His widow, Mary Watts took over the running of the project. In 1906, after making 24 memorial tablets for the project, William De Morgan abandoned the ceramics business to become a novelist. It was a bit of a blow to the project. The only ceramics firm able to manufacture appropriate further tiles was Royal Doulton. Mary was dissatisfied with Royal Doulton’s designs, and preoccupied with the management of the Watts Gallery and Watts Mortuary Chapel in Compton, Surrey. Eventually, Mary Watts lost interest in the project. Work to complete it was sporadic and ceased altogether in 1931 with only 53 of the planned 120 tiles in place. I think it is very sad that such an amazing project was sidelined…for lack of interest!! Seriously, lack of interest!! Finally, in 2009, the Diocese of London consented to  further additions to the memorial, and the first new tablet in 78 years was added. In my opinion, it’s about time.

further additions to the memorial, and the first new tablet in 78 years was added. In my opinion, it’s about time.

As interest grew again, a mobile app was created in 2013. It was called The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park. Once again, interest wained…at least for the app, so it is now discontinued. The app provided a detailed account of the fifty-four incidents commemorated on the Memorial when a visitor scanned its plaque with a handheld device. Again, I find myself feeling sad that people can possible lose interest in the everyday heroes in our world. They are each amazing, and they should never be forgotten.

I read a story about training an elephant yesterday. It went like this, “As a man was passing the elephants, he suddenly stopped, confused by the fact that these huge creatures were being held by only a small rope tied to their front leg. No chains, no cages. It was obvious that the elephants could, at anytime, break away from their bonds but for some reason, they did not.

I read a story about training an elephant yesterday. It went like this, “As a man was passing the elephants, he suddenly stopped, confused by the fact that these huge creatures were being held by only a small rope tied to their front leg. No chains, no cages. It was obvious that the elephants could, at anytime, break away from their bonds but for some reason, they did not.

He saw a trainer nearby and asked why these animals just stood there and made no attempt to get away. ‘Well,’ trainer said, ‘when they are very young and much smaller we use the same size rope to tie them and, at that age, it’s enough to hold them. As they grow up, they are conditioned to believe they cannot break away. They believe the rope can still hold them, so they never try to break free.’

The man was amazed. These animals could at any time break free from their bonds, but because they believed they couldn’t, they were stuck right where they were.”

The story made me think about the way Hitler was able to train a generation to follow him without question. He took the children away from their parents when they were young, basically telling the parents that the state knew what was best for the children, and the parents didn’t know enough about educating the children to do a good job. He set up the Hitler Youth organization in 1933 for educating and training male youth in principles. Of course, the principles Hitler had in mind were vastly different from any that the parents could imagine. Hitler’s ideas included racism, killing any “undesirables” among the population, and controlling the people with curfews and lockdowns…to name a few. Under the leadership of Baldur Benedikt von Schirach, the head of all German youth programs, the Hitler Youth included by 1935 almost 60 percent of German boys. On July 1, 1936, it became a state agency that all young “Aryan” Germans were expected to join. Upon reaching his 10th birthday, a German boy was registered and investigated especially for “racial purity” and, if qualified, inducted into the “German Young People.” At age 13 the youth became eligible for the Hitler Youth, from which he was graduated at age 18. Throughout these years he lived a life of dedication, fellowship, and Nazi conformity, generally with minimum parental guidance. From age 18 he was a member of and served in the state labor service and the armed forces until at least the age of 21.

Two leagues also existed for girls. The League of German Girls trained girls ages 14 to 18 for comradeship, domestic duties, and motherhood. “Young Girls” was an organization for girls ages 10 to 14. The girls were expected to have babies to build the Reich…provided they qualified as “racially pure,” of course.

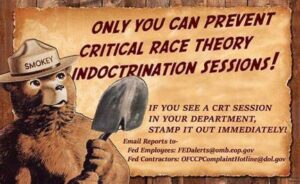

In the tumultuous days we currently live in, parents need to be very involved in what our children are being taught. The current racially charged climate in our nation would only be exacerbated by teaching our children things like Critical Race Theory, because it is really the new Ku Klux Klan. Racism, against any nationality is simply wrong…there is no gray area. Our children need to be able to be proud of the race they are and the background they come from. Racism is unacceptable, against any race, and we, as parents, grandparents, and

even great grandparents, need to kick the government out of our educational system, and get back to decent moral values. We need to stop the insanity in our schools, and teach our kids the true history of our nation. We must teach good values, and our children need to be taught to accept all races. We need to start with the kids, because they are the future leaders.

even great grandparents, need to kick the government out of our educational system, and get back to decent moral values. We need to stop the insanity in our schools, and teach our kids the true history of our nation. We must teach good values, and our children need to be taught to accept all races. We need to start with the kids, because they are the future leaders.