History

When a plane comes down, there is always a reason. It might be mechanical, weather, the human factor, or a combination of these. Most often we don’t know the real and complete cause for a long time. On October 4, 1992, an El-Al Boeing 747 cargo jet was scheduled to bring 114 tons of computers, machinery, textiles and various other materials from Amsterdam to Tel Aviv, Israel. At 6:30pm that Sunday, Captain Isaac Fuchs piloted the jet, carrying two other pilots and one passenger, out of Schipol Airport in good weather. It was set to be a nice flight, but just minutes after takeoff, fires suddenly broke out in the plane’s third and fourth engines. Just as suddenly, they fell right off the wing. Of course, this threw the crew for a loop…literally!!

When a plane comes down, there is always a reason. It might be mechanical, weather, the human factor, or a combination of these. Most often we don’t know the real and complete cause for a long time. On October 4, 1992, an El-Al Boeing 747 cargo jet was scheduled to bring 114 tons of computers, machinery, textiles and various other materials from Amsterdam to Tel Aviv, Israel. At 6:30pm that Sunday, Captain Isaac Fuchs piloted the jet, carrying two other pilots and one passenger, out of Schipol Airport in good weather. It was set to be a nice flight, but just minutes after takeoff, fires suddenly broke out in the plane’s third and fourth engines. Just as suddenly, they fell right off the wing. Of course, this threw the crew for a loop…literally!!

Captain Fuchs knew he needed to dump the plane’s fuel and he spotted a lake nearby. He assumed he would have enough time to dump the fuel and then head back to the airport, but the plane did not have enough power to make the return trip. They were six miles short of the airport when Fuchs radioed, “Going down,” and the plane plunged straight into an apartment building in the Bijimermeer section of Amsterdam. The crash was followed by a massive fireball that exploded through the building. Firefighters rushed to the scene. The fire was horrific, and by the time the fire was under control, about 100 people were dead. No one knew the exact number, because the explosion made body identification extremely difficult. Unfortunately, the building housed mainly undocumented immigrants from Suriname and Aruba, also  making the number of casualties harder to ascertain.

making the number of casualties harder to ascertain.

When the accident investigation was completed, it was found that like a similar accident in Taiwan less than a year earlier, the problem was found to be related to a fuse pin, part of the mechanism that binds the engines to the wings, so in both cases, the problem was caused by fatigue and the ultimate failure of this part. Sadly, it often takes a tragedy of this magnitude to bring about the change that puts closer inspections in play. Of course, the ultimate price paid is in the lives lost.

Many of us have heard of “dance mania” or “dance fever,” but I wonder how many people realize that those were real things. There have been a number of times in history when people were suddenly compelled to dance without stopping. In fact, they really couldn’t stop until they fell down with exhaustion. Then they would sleep a while, and start all over again. Many times the victim of this disease, would cry out in pain, begging someone to help them. They could not stop. Their feel would blister and bleed. Their muscles would spasm. Tears would flow from their eyes, but still they danced. Some people danced until they actually fell down dead.

Many of us have heard of “dance mania” or “dance fever,” but I wonder how many people realize that those were real things. There have been a number of times in history when people were suddenly compelled to dance without stopping. In fact, they really couldn’t stop until they fell down with exhaustion. Then they would sleep a while, and start all over again. Many times the victim of this disease, would cry out in pain, begging someone to help them. They could not stop. Their feel would blister and bleed. Their muscles would spasm. Tears would flow from their eyes, but still they danced. Some people danced until they actually fell down dead.

The Strasbourg plague started with Frau Troffea in July of 1518. That day, she just stepped outside her small home in Strasbourg and started to dance. She might have seemed happy, but she didn’t stop. Frau Troffea danced the entire day. Her husband was not happy. No cleaning was done, no cooking, and if they had children, they weren’t taken care of either. She only stopped dancing when she collapsed that night for a few hours of restless sleep. Then, with the sun rise, she began dancing again. To the horror of her husband, a crowd gathered around his dancing wife, who swayed to the sound of silence. There was no music…except maybe in her head. She paid no attention to anything going on around her. She just danced, even though her feet were bloody and bruised. It was almost as if she was just crazy, but that couldn’t be it, because within days, at least thirty other dancers had joined Frau Troffea. It was just the beginning of the strangest plague to strike medieval Europe. The people called it “dancing mania,” and it soon spread to even more people in Strasbourg. A reporter at that time, Daniel Specklin said that there were “more than one hundred” dancing at the same time. Someone else estimated the number at closer to four hundred. The strange epidemic quickly became a crisis for the city of Strasbourg, and the city council had no idea how to stop the dancing, which is a strange idea to me anyway. What could the city council do, if the doctors couldn’t help?

The only thing anyone was sure of, was that…the dancers were not happy. They writhed in pain. They begged for mercy. They screamed for help. As summer stretched on, the dancing epidemic started to claim lives. One chronicle reported that during the heat of the summer, as many as fifteen people died every day from dancing. It makes sense, they probably couldn’t stop to eat or drink. Exhaustion, dehydration, and starvation finally took their toll, and the victim simply died. Thinking it might be a curse, the city cracked down on the possible connection to sin. Brothels and gambling houses were closed. Everyone knew that gaming and prostitution angered the saints, who might have sent the dancing plague to punish Strasbourg. So, the city rounded up all the “loose persons” and banished them from the city. It didn’t help. They prayed and lit candles, hoping that a return to their faith might lift the “curse” for the town. They banned dancing, effectively making all the victims, “criminals” as well.

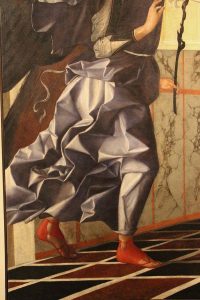

Desperate, as the end of summer neared and the dancing mania continued, the city took a drastic step. A reporter of the time described the cure. “They sent many on wagons to St. Vitus,” a shrine at the top of a mountain. The dancers continued to fall down in front of the altar, so the priest said Mass over them, and “they were given a little cross and red shoes, on which the sign of the cross had been made in holy oil, on both the

tops and the soles.” It was thought that they were possessed. The red shoes did the trick. The dancing epidemic slowly came to an end, and most of the dancers regained control of their bodies. The strange ailment started to be called “St. Vitus’ Dance,” either because the saint had cured the dancers, or because he was responsible for the original curse. Strange idea either way. Whether they were possessed, or the “illness” just ran it’s course, the trip to Saint Vitus marked the beginning of the end of the Dancing Plague. It is now believed that the people suffered from mass hysteria, due to the stresses of the day. A Small Pox plague and a Leprosy plague had been through the area, as well as several years of failed crops and famine. It makes sense I guess, but what a strange way for it to manifest. Apparently, a trip to the church to see the priest was enough to calm their fears and stop the plague.

tops and the soles.” It was thought that they were possessed. The red shoes did the trick. The dancing epidemic slowly came to an end, and most of the dancers regained control of their bodies. The strange ailment started to be called “St. Vitus’ Dance,” either because the saint had cured the dancers, or because he was responsible for the original curse. Strange idea either way. Whether they were possessed, or the “illness” just ran it’s course, the trip to Saint Vitus marked the beginning of the end of the Dancing Plague. It is now believed that the people suffered from mass hysteria, due to the stresses of the day. A Small Pox plague and a Leprosy plague had been through the area, as well as several years of failed crops and famine. It makes sense I guess, but what a strange way for it to manifest. Apparently, a trip to the church to see the priest was enough to calm their fears and stop the plague.

As a part of his planned world takeover, Hitler had sent his forces to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941. Early on it had become one relentless push inside Russian territory, but the Nazis experienced their first setback in August, when the Soviet Army’s tanks drove the Germans back from the Yelnya salient. A shocked Adolf Hitler told General Bock at the time, “Had I known they had as many tanks as that, I’d have thought twice before invading.” Personally, I doubt that it would have made any difference. Hitler did not particularly care about the lives of his men, just that they perform as they were ordered. For the men, there was no turning back because Hitler would not be moved. Hitler firmly believed that he was destined and well able to succeed in dominating the Soviet Union and capturing Moscow, where others had failed.

As a part of his planned world takeover, Hitler had sent his forces to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941. Early on it had become one relentless push inside Russian territory, but the Nazis experienced their first setback in August, when the Soviet Army’s tanks drove the Germans back from the Yelnya salient. A shocked Adolf Hitler told General Bock at the time, “Had I known they had as many tanks as that, I’d have thought twice before invading.” Personally, I doubt that it would have made any difference. Hitler did not particularly care about the lives of his men, just that they perform as they were ordered. For the men, there was no turning back because Hitler would not be moved. Hitler firmly believed that he was destined and well able to succeed in dominating the Soviet Union and capturing Moscow, where others had failed.

So, on October 2, 1941, the Germans began their surge toward Moscow, led by the 1st Army Group under the General Fedor von Bock. The Germans and Hitler thought they could come in and mow the people down with no resistance. Then they thought they could take their resources from the people to sustain them through the winter months, while they continued to plunder the country. The Russian peasants had different ideas, however.  As the Germans approached, the peasants in their path employed a “scorched earth” policy. I’m not a veteran or anything, so somehow I hadn’t heard of this strategy. The idea is to destroy anything and everything that could be useful to the enemy.

As the Germans approached, the peasants in their path employed a “scorched earth” policy. I’m not a veteran or anything, so somehow I hadn’t heard of this strategy. The idea is to destroy anything and everything that could be useful to the enemy.

This strategy could prove especially useful for the Soviet Union because of the harsh Russian winter. The Russians remembered Napoleon and the fateful winter he and his men spent in the frigid Russian winter. The peasants began destroying everything as they fled their villages, fields, and farms. Harvested crops were burned, livestock were driven away, and buildings were blown up, leaving nothing of value behind to support exhausted troops. Hitler’s army invaded Russia to find nothing but ruins. On top of the lack of shelter and food, winter was upon them, and they were in trouble.

Hitler was a stubborn cuss, and although some German generals had warned him against launching Operation Typhoon as the harsh Russian winter was just beginning, he would not be moved. The generals remembered the fate of Napoleon, who got stuck in horrendous conditions. Over the course of that winter, Napoleon lost  serious numbers of men and horses. Still, some people urged him on. This encouragement, coupled with the fact that the German army had taken the city of Kiev in late September, caused Hitler to declare, “The enemy is broken and will never be in a position to rise again.” So for 10 days, starting October 2, the 1st Army Group drove east, drawing closer to the Soviet capital each day, but by the time the operation was over on January 7, 1942, the German army had not reached Moscow. German casualties amounted to 460,000 men, many of whom were frozen to death due to the lack of proper clothing to handle the harsh Russian winters. It was a catastrophic loss to the the German army.

serious numbers of men and horses. Still, some people urged him on. This encouragement, coupled with the fact that the German army had taken the city of Kiev in late September, caused Hitler to declare, “The enemy is broken and will never be in a position to rise again.” So for 10 days, starting October 2, the 1st Army Group drove east, drawing closer to the Soviet capital each day, but by the time the operation was over on January 7, 1942, the German army had not reached Moscow. German casualties amounted to 460,000 men, many of whom were frozen to death due to the lack of proper clothing to handle the harsh Russian winters. It was a catastrophic loss to the the German army.

When Hitler began his “Final Solution,” the Jewish people and several other groups of people had no idea what was coming their way. As people began to disappear and their families began to realize that Hitler was going to kill all of them, they began, in a panic, to try to figure out a way out of the German occupied areas of Europe. By the time people realized that they were in deep trouble, it was often too late, or nearly too late. Walls and fences surrounded them, with armed guards set up at all entrances to keep the people inside their prison walls. There seemed to be no way out.

When Hitler began his “Final Solution,” the Jewish people and several other groups of people had no idea what was coming their way. As people began to disappear and their families began to realize that Hitler was going to kill all of them, they began, in a panic, to try to figure out a way out of the German occupied areas of Europe. By the time people realized that they were in deep trouble, it was often too late, or nearly too late. Walls and fences surrounded them, with armed guards set up at all entrances to keep the people inside their prison walls. There seemed to be no way out.

This was where the resistance really came in. Some of the resistance personnel were Jewish people in the camps or towns, but some were the Christian citizens of the towns. They were not Jewish, and were not in trouble, but the felt a deep love for humanity and a deep sense of wrong and right. They could not stand by and do nothing, while people were killed. They took people into their homes, and built hiding places for them. Extra walls were built into rooms, making them slightly smaller, but providing a tiny space where the Jewish people they were helping could take refuge. It was a huge risk,  because if they were caught helping the Jewish people, they would be killed or sent to the work camps.

because if they were caught helping the Jewish people, they would be killed or sent to the work camps.

The Jewish people who were being hidden no longer had access to ration cards, so they could not buy food. The people who were hiding them had to share their food, meaning their own meager rations had to feed more people that before. Everyone lost weight. Everyone became weaker. People learned to find roots, mushrooms, berries and anything else they could forage in the forests…when they could get to the forest. Everyone was thinner in those days…dangerously thin, especially the Jewish people.

People, like Corrie ten Boom, who helped the Jewish people, gypsies, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, took great risks. Sometimes, they were turned in by their neighbors…for the reward money the Nazis offered. Other people hated the Jewish people as much as Hitler, and they turned them in out of hate. They didn’t care if there  was a reward or not. Some people were as full of hate as the Nazis. Nevertheless, While the Nazis and the Nazi sympathizers were filled with hate, many people of that era were filled with love for their fellowman, and did not see the race, religious, or cultural differences. They just saw people, and knew they could not stand by, witnesses to the slaughter, and do nothing. The integrity of these people makes me wonder why things can’t be that way in our times. The best way bring change in any society is through love for one another…not hate. The people who fought against the Nazis and showed compassion for the Jewish people, gypsies, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, were willing to die to save people…not to destroy them.

was a reward or not. Some people were as full of hate as the Nazis. Nevertheless, While the Nazis and the Nazi sympathizers were filled with hate, many people of that era were filled with love for their fellowman, and did not see the race, religious, or cultural differences. They just saw people, and knew they could not stand by, witnesses to the slaughter, and do nothing. The integrity of these people makes me wonder why things can’t be that way in our times. The best way bring change in any society is through love for one another…not hate. The people who fought against the Nazis and showed compassion for the Jewish people, gypsies, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, were willing to die to save people…not to destroy them.

Many people use escalators every day. They have become a part of our everyday life, however, it is said that people used to be really frightened of them. When they were first introduced on the London Underground, the executives for the escalator’s manufacturer, Mowlem and Cochrane asked a one-legged man named William Harris to demonstrate how safe the new-fangled contraptions were. The man rode up and down to show that those who took it were unlikely to lose their balance.

Many people use escalators every day. They have become a part of our everyday life, however, it is said that people used to be really frightened of them. When they were first introduced on the London Underground, the executives for the escalator’s manufacturer, Mowlem and Cochrane asked a one-legged man named William Harris to demonstrate how safe the new-fangled contraptions were. The man rode up and down to show that those who took it were unlikely to lose their balance.

While I can say that it is not likely that a person would lose their balance on an escalator, I can also say, from personal experience that losing your balance is not the only way, or even the most likely way for someone to end up on the steps of the escalator on their knees. I suppose that you could say that I have Escalaphobia…or at least did have. It is something I have been able to work through in the almost 56 years since my escalator experience occurred. I was five years old at the time, and people were invited to come into First Interstate Bank and look around. The big story of the day was the escalator. As my mother was preparing to take her daughters down the escalator, I was placed on first, then Mom had to get my sister on and hold the baby. Someone stepped on between me and my sisters and mom. In front of me, an older woman panicked when it came time to get off. She back-stepped, and I fell. As the escalator tore at my dress, knees, elbows, and chin, somehow missing my long hair, I let out a scream that could have been heard all over town. The bank president came running over, saying, “Please don’t sue!! We will buy her a new dress and pay all the medical bills!!” Of course, my mom had no intention of suing them. That didn’t happen much in those days.

My wounds healed, and I got a new dress, but the scars remain to this day, and the mental scars were even worse. Every time I stepped on an escalator, my heart thumped and my knees shook. I always had to make  sure I took a second or two to center my foot on the step. I watched as people tried to keep walking as the escalator moved. That would never be me. I was on the step, and I was watching for the point when I would need to step off of it. After many years, I thought I was feeling pretty secure in getting on and off of an escalator, when my niece, Liz Masterson and I went into the Mall of America a few years ago. As I stepped on the escalator, thinking I had squared my foot, but apparently not quite, I stood there, and as the step behind me moved, it scratched my calf, drawing blood. I couldn’t believe it!! I probably felt at ease for the first time…and look what it had gotten me. Once again, an escalator had cut my skin. I can’t say that I truly have Escalaphobia, but if you don’t mind…I’ll take the stairs.

sure I took a second or two to center my foot on the step. I watched as people tried to keep walking as the escalator moved. That would never be me. I was on the step, and I was watching for the point when I would need to step off of it. After many years, I thought I was feeling pretty secure in getting on and off of an escalator, when my niece, Liz Masterson and I went into the Mall of America a few years ago. As I stepped on the escalator, thinking I had squared my foot, but apparently not quite, I stood there, and as the step behind me moved, it scratched my calf, drawing blood. I couldn’t believe it!! I probably felt at ease for the first time…and look what it had gotten me. Once again, an escalator had cut my skin. I can’t say that I truly have Escalaphobia, but if you don’t mind…I’ll take the stairs.

Trips across the United States in the mid-1800’s were slow and often treacherous. The trips were taken on wagons pulled by horses or oxen. It took months to get across the nation, and many people did not make it. Illness, Indian attacks, heat, cold, or animal bites, all served to cause problems, but one of the worse dangers was water. Of course, water could be bad and filled with bacteria, but more importantly, water, in the form of rivers could make crossing extremely dangerous and sometimes deadly. Rivers that were swift or deep, could mean the end for wagons, animals, and for people.

Trips across the United States in the mid-1800’s were slow and often treacherous. The trips were taken on wagons pulled by horses or oxen. It took months to get across the nation, and many people did not make it. Illness, Indian attacks, heat, cold, or animal bites, all served to cause problems, but one of the worse dangers was water. Of course, water could be bad and filled with bacteria, but more importantly, water, in the form of rivers could make crossing extremely dangerous and sometimes deadly. Rivers that were swift or deep, could mean the end for wagons, animals, and for people.

One such danger, located on the Oregon Trail, where emigrants made their way to Oregon, California, and Utah, was the North Platte River near present day Casper, Wyoming. In those days, there were many people looking to make a living in something besides the gold industry, which wasn’t always successful for the majority of people, so they set up things like commercial ferries to transport wagon trains across the treacherous rivers, like the North Platte River. It was a safer way to cross the rivers, to be sure, but it was also expensive, and so many people tried to cross on their own. Mostly due to their inexperience, many people lost everything trying to cross, sometimes even their lives. Many emigrants, unwilling to pay, tried to fashion their own “ferries,” with varying success. Until bridges were built, nearly all travelers swam their livestock across, and many people and animals drowned in the swift, deep, shockingly cold water of the Platte.

From present-day central Nebraska to South Pass in west-central Wyoming, emigrants to California, Oregon and Utah all took more or less one route. Most of the wagon trains came up the south side of the Platte from Fort Kearney. They crossed the South Platte in western Nebraska where the river forks, and continued west, going up the south side of the north fork. This route meant that they would have to ford the Laramie River where it joined the North Platte at Fort Laramie. Then, finally they could cross the North Platte itself 150 miles later, where the river turned to go to the south near present Casper. Once they made the treacherous North Platte River crossing, the travelers could continue on to the west. There was simply no other way to get there from the East at that time in history.

Routes changed periodically, including crossings at Red Buttes, west of Casper during fur-trade times in the  1820s and 1830s. Crossing points varied more and more during the mid-1840s, including along 25 miles of river from the mouth of Deer Creek, at present-day Glenrock, Wyoming to Casper, Wyoming. Many people crafted small boats by emptying their wagons, removing the wagon box from the running gear, caulking the boxes water tight with tar, dismantling the running gear into pieces, and then ferrying everything across the water in the wagon boxes. Wow!! What a long drawn out, time consuming way to build a boat. Them they used poles or oars for guidance and often using ox or human power to tow the craft across the water with long ropes. This was a fairly reliable method, as I said very slow due to the unloading, dismantling, and reloading.

1820s and 1830s. Crossing points varied more and more during the mid-1840s, including along 25 miles of river from the mouth of Deer Creek, at present-day Glenrock, Wyoming to Casper, Wyoming. Many people crafted small boats by emptying their wagons, removing the wagon box from the running gear, caulking the boxes water tight with tar, dismantling the running gear into pieces, and then ferrying everything across the water in the wagon boxes. Wow!! What a long drawn out, time consuming way to build a boat. Them they used poles or oars for guidance and often using ox or human power to tow the craft across the water with long ropes. This was a fairly reliable method, as I said very slow due to the unloading, dismantling, and reloading.

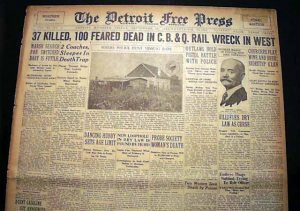

Rain…most often a welcome sight, especially during the hot summer months, and sometimes early fall months too. The Casper, Wyoming area is not one to get a lot of rain, however. Nevertheless, the rain had been coming down heavily for a week, that late September of 1923. In fact there had been three straight days of downpour. The railroad personnel were keeping a close eye on the rivers, creeks, and bridges. They were concerned, but did not expect the volatile, and possibly catastrophic situation that could be heading their way. Cole Creek was reported to have less than 16 inches of rainwater in its bed and by 8pm on September 27th, and the bridge was believed secure. Hours later, the water level would reportedly rise two feet in half an hour.

Rain…most often a welcome sight, especially during the hot summer months, and sometimes early fall months too. The Casper, Wyoming area is not one to get a lot of rain, however. Nevertheless, the rain had been coming down heavily for a week, that late September of 1923. In fact there had been three straight days of downpour. The railroad personnel were keeping a close eye on the rivers, creeks, and bridges. They were concerned, but did not expect the volatile, and possibly catastrophic situation that could be heading their way. Cole Creek was reported to have less than 16 inches of rainwater in its bed and by 8pm on September 27th, and the bridge was believed secure. Hours later, the water level would reportedly rise two feet in half an hour.

On September 27, 1923, The Chicago Burlington and Quincy Number 30 passenger train left Casper for Denver at approximately 8:30pm with approximately 60-70 passengers on board. the exact number is unknown. The train reached Cole Creek by 9:15pm and approached the Cole Creek bridge shortly after. Unexpectedly, Number 30 attempted to slow, and eventually braked upon realizing the usually dry gully below was now a torrent of rushing water and vision was severely limited. It is unknown if the rushing water was unnerving or if they saw something of the impending disaster through the rain, but they did attempt to slow down. Unfortunately, the bridge’s trestle had already been washed out or badly weakened. The realization of the situation came too late for the crew of CBQ number 30.

The 100-ton locomotive engine and first five, of seven train cars plummeted into the sand and water below. Most of the passengers were in two of these cars. Ans the cars hit, metal crunched, windows and doors burst under flood of water, steam from the engine scalded passengers and worse, and it would take more than an hour for help to arrive, especially when the first call to the Casper dispatcher’s office didn’t come for 45 minutes. From that point, the city sprang into action. Emergency news alerts calling for doctors and volunteers flashed across movie screens in town. The residents first thought it was a refinery disaster…which was much more expected here than a train wreck. Instead, however, they were faced with the greatest train wreck in Wyoming’s history, as it would come to be known.

Try as they might, rescue crews could do very little until the following morning. At first, bodies were found washed down the North Platte River for hundreds of yards, but they would eventually reach miles down the river. The massive recovery efforts would continue for weeks. The cleanup ended October 15, still daily reports were provided by local newspapers and radio. There were still people missing, but winter was upon them, and anyone who lives near the Platte River, or it’s tributaries, knows that once the ice sets in, bodies remain hidden  beneath the surface.

beneath the surface.

The body of the train’s conductor, Guy Goff, was found seven months later, in May 1924, washed down the North Platte. Engineer, Ed Spangler, was discovered in January of the following year. In all, the cost of the wreck totaled close to a million dollars and 31 deaths are reported, although the final number remains uncertain because of the discrepancy in passenger numbers. The day after the wreck, a nine-year-old boy was seen searching for days for his father at the wreck site. No confirmation was received that the man was ever found.

There are many heroes in World War II, and many of their stories are never told. Many of them just did their job and went on to the next mission. It’s the ones who got shot down, sunk, shot on the ground, or captured that always seem to be remembered. It’s the way of things, I guess, but sometimes someone come across a story of bravery that is so intriguing that it must be told.

There are many heroes in World War II, and many of their stories are never told. Many of them just did their job and went on to the next mission. It’s the ones who got shot down, sunk, shot on the ground, or captured that always seem to be remembered. It’s the way of things, I guess, but sometimes someone come across a story of bravery that is so intriguing that it must be told.

Owen John Baggett was born on August 29, 1920, in Graham, Texas to John M. and Mary Pearl Baggett. He was always known for his quick smile and kind words. He graduated from Hardin–Simmons University in 1941, where he was the band’s drum major. After graduation, he was employed as a defense contractor on Wall Street. Baggett enlisted in the Army Air Forces and graduated from pilot training on July 26, 1942, at the New Columbus Army Flying School. Baggett achieved the rank of second lieutenant and was a member of the 7th Bomb Group based at Pandaveswar, in India, during the World War II.

On March 31, 1943, while stationed in British India, Baggett’s squadron, was ordered to destroy a bridge at Pyinmana, Burma. It was a dangerous mission, as the bridge would be heavily guarded. Before the squadron could reach their target, the 12 B-24s of 7th Bomber Group were intercepted by 13 Ki-43 fighters of 64 Sentai Imperial Japanese Army Air Service. Almost immediately, Baggett’s plane was severely damaged and was set on fire by several hits to the fuel tanks. There would be no recovery from this, and the crew was forced to bail out. They escaped the crippled B-24 only seconds before it exploded. Then began the next horror. The Japanese pilots began attacking the US airmen as they parachuted to earth. This was a brutal practice designed to insure that the airmen could be rescued, smuggled out of occupied territory, and put back in the air to fight anther day. Two of the crewmen were killed in the air. It was at first thought that the pilot, Lloyd K. Jensen was “summarily executed”, but he actually survived the war. Baggett, who had been wounded, decided to play dead, hoping the enemy pilots would ignore him, but one Ki-43 fighter flew close to Baggett and slowed to make sure. The opportunity was too good to pass up, and when Baggett saw the pilot open his canopy and decided to take a chance. He drew his .45 caliber M1911 pistol and fired four shots at the pilot. He was a good shot, and the bullets hit their mark. Baggett watched as the plane stalled and plunged toward the ground.

My guess is that Baggett had no idea of the enormity of his actions. He later found out that he was famous. Baggett was the only person ever to shoot down an aircraft using a pistol. Of course, in true Japanese style, they claimed that “no Japanese planes were lost during this action. They said that the pilot (wounded or not) regained control of his aircraft and flew it back to his airfield.” I submit that they weren’t there. Still, Baggett hadn’t seen it either, but his doubt came to an end when his paths crossed with Colonel Harry Melton, commander of the 311th Fighter Group, who had also been shot down that day. Melton saw the plane, and could confirm that Baggett had shot down an enemy plane with a simple .45 caliber handgun. It was an amazing feat of multi-tasking. Baggett, of course, still had to land and was immediately captured by Japanese soldiers on the ground. He remained a prisoner of the Japanese for the rest of the war…2½ years. Baggett and 37 other POWs were liberated at the war’s end by eight OSS agents who parachuted into Singapore.

Baggett was always grateful that his life was spares, and wanted to give back. While he was assigned to Mitchel Air Force Base, Baggett was noted for his work with children, including sponsoring a boy and a girl to be commander for a day. In 1973, at the age of 53, Baggett retired from the Air Force as a colonel. He later worked as a defense contractor manager for Litton. Retired Colonel Owen Baggett died at peace and dignity July 27, 2006 in New Braunfels, Texas.

Baggett was always grateful that his life was spares, and wanted to give back. While he was assigned to Mitchel Air Force Base, Baggett was noted for his work with children, including sponsoring a boy and a girl to be commander for a day. In 1973, at the age of 53, Baggett retired from the Air Force as a colonel. He later worked as a defense contractor manager for Litton. Retired Colonel Owen Baggett died at peace and dignity July 27, 2006 in New Braunfels, Texas.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

The men who built these trains became so skilled at their work, that on December 10 – 11, 1891, the Great Eastern Railway’s Stratford Works built one of these locomotives and had it “in steam” with a coat of grey primer in 9 hours 47 minutes. That feat remains a world record. The locomotive then went off to run 36,000 miles on Peterborough to London coal  trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

Because of their light weight the locomotives were given the Route Availability (RA) number 1, indicating that they could work over nearly all routes. Steam engine trains are generally safe, and still used to this day, although not in modern transport situations. Still, they can pose a problem in certain situations. Just like boilers in homes and commercial buildings, too much pressure that is not alleviated presents a huge danger.

On September 25, 1900, at 8:45am, GER Class Y14 0-6-0 locomotive Number 522, just a year old at the time,  stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

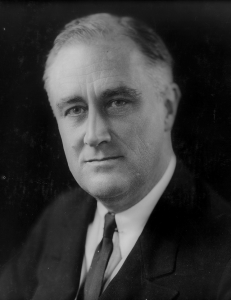

A sneak attack…not something that happens overnight. That kind of attack takes planning. Relations between the United States and Japan had not been good, but now with Japan’s occupation of Indo-China and the implicit menacing of the Philippines, an American protectorate, they were deteriorating rapidly. The Americans had retaliated by seizing of all Japanese assets in the United States. That action was followed by the closing of the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt issued a statement, drafted by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, that threatened war between the United States and Japan should the Japanese encroach any farther on territory in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific.

A sneak attack…not something that happens overnight. That kind of attack takes planning. Relations between the United States and Japan had not been good, but now with Japan’s occupation of Indo-China and the implicit menacing of the Philippines, an American protectorate, they were deteriorating rapidly. The Americans had retaliated by seizing of all Japanese assets in the United States. That action was followed by the closing of the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt issued a statement, drafted by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, that threatened war between the United States and Japan should the Japanese encroach any farther on territory in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific.

The Japanese were keen to wield more power on the people of the earth. To do that, they had to take down the biggest super power, the United States of America. And to protect themselves, they needed to take Hawaii out of the hands of the United States, because it was a gateway in the Pacific that they couldn’t afford to have in the hands of the Allies. On September 24, 1941, the Japanese consul in Hawaii was instructed to divide Pearl Harbor into five zones, calculate the number of battleships in each zone, and report the findings back to Japan. They were preparing for the attack they had planned for December.

The Japanese military had long dominated Japanese foreign affairs. The official negotiations between the United States secretary of state and his Japanese counterpart to ease tensions were still ongoing, but Hideki Tojo, the minister of war who would soon be prime minister, had no intention of withdrawing from captured territories…even if the negotiations required it. He also decided that the American “threat” of war as an ultimatum, and he made plans to attack first in a Japanese-American confrontation: the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

As the plans began to gear up, Japan didn’t know that the United States had intercepted the message. Most unfortunate, was the fact that the message was sent back to Washington for decrypting. There were not a lot of

flights east, so the message was sent via sea. That process took more time. When it finally arrived at the capital, staff shortages and other priorities further delayed the decryption. When the message was finally unscrambled in mid-October, it was dismissed as being of no great consequence. It was a huge error on the part of the American intelligence community, and on December 7th, everyone would know that.

flights east, so the message was sent via sea. That process took more time. When it finally arrived at the capital, staff shortages and other priorities further delayed the decryption. When the message was finally unscrambled in mid-October, it was dismissed as being of no great consequence. It was a huge error on the part of the American intelligence community, and on December 7th, everyone would know that.