History

World War II brought with it, something of an anomaly when it came to Japanese pilots…the Kamikaze pilot. It is said that these men “volunteered” for these mission. In an act that can only be described as insane, they flew their fighter planes straight into the ships of the enemy. Most people can’t imagine doing such a thing, and we might even assume that these pilots were really wanting to commit suicide. Most often that was not the case, although I suppose there may have been some who wanted to go down in “a blaze of glory” for their country.

World War II brought with it, something of an anomaly when it came to Japanese pilots…the Kamikaze pilot. It is said that these men “volunteered” for these mission. In an act that can only be described as insane, they flew their fighter planes straight into the ships of the enemy. Most people can’t imagine doing such a thing, and we might even assume that these pilots were really wanting to commit suicide. Most often that was not the case, although I suppose there may have been some who wanted to go down in “a blaze of glory” for their country.

The Japanese government had a unique way of accomplishing what they wanted done. When the new soldiers came into the camps, they were given a piece of paper with three options listed on it. They could volunteer willingly, simply volunteer, or not volunteer. Because the pilots names were on the papers, they felt intimidated. The pressure was intense, and  not only to volunteer as kamikaze pilots, but they would jump off a cliff so that they would not be captured. I guess I can understand the fear of capture, but I don’t know that I could take my own life as a means of escaping capture. Most people have such a strong survival instinct that in situations that seem hopeless, they would rather sacrifice a limb than their lives. In fact one such case, a man had been fishing when a boulder rolled down a hill and pinned his hand. He tried everything he could think of to free his hand, and then when there was no other option, he actually chewed his hand off, and got himself to the hospital for treatment. You might say, “well, his hand was probably dead anyway,” and you might be right, but would that inspire you to chew your hand off? I don’t think so, nevertheless, he did it, in order to live. And yet, these Kamikaze pilots flew into planes, ships, or buildings to take out as many people as they could, and in the event of being overtaken by the enemy, they chose suicide.

not only to volunteer as kamikaze pilots, but they would jump off a cliff so that they would not be captured. I guess I can understand the fear of capture, but I don’t know that I could take my own life as a means of escaping capture. Most people have such a strong survival instinct that in situations that seem hopeless, they would rather sacrifice a limb than their lives. In fact one such case, a man had been fishing when a boulder rolled down a hill and pinned his hand. He tried everything he could think of to free his hand, and then when there was no other option, he actually chewed his hand off, and got himself to the hospital for treatment. You might say, “well, his hand was probably dead anyway,” and you might be right, but would that inspire you to chew your hand off? I don’t think so, nevertheless, he did it, in order to live. And yet, these Kamikaze pilots flew into planes, ships, or buildings to take out as many people as they could, and in the event of being overtaken by the enemy, they chose suicide.

Of course, their beliefs were similar to those of the Muslim suicide bombers. They somehow think that there is honor in these acts. In reality, the Kamikaze pilot doesn’t even think about the enemy. It’s really not about the enemy. They think about the “honor” they have been given to give up their life for the emperor. Well, I would give up my life rather than turn my back on God, and I suppose that is sort of what they are doing, but when  the country’s leader becomes your “god,” you are already in a lot of trouble. That is basically the position the Kamikaze pilots found themselves in. They had been conditioned to unquestioningly die for the emperor. Kamikaze Pilots Believed They Would Meet Again At The Yasukuni Shrine…similar to the seventy virgins, I guess. The only soldiers who were exempt from being Kamikaze pilots were firstborn sons. The only other way out was engine trouble, in which case, they could live to die another day. Some of the pilots even faked engine trouble to stay alive, but in the end, they hated themselves so much for doing so, that on the next mission, they did their “duty” to their emperor. Amazing, isn’t it?

the country’s leader becomes your “god,” you are already in a lot of trouble. That is basically the position the Kamikaze pilots found themselves in. They had been conditioned to unquestioningly die for the emperor. Kamikaze Pilots Believed They Would Meet Again At The Yasukuni Shrine…similar to the seventy virgins, I guess. The only soldiers who were exempt from being Kamikaze pilots were firstborn sons. The only other way out was engine trouble, in which case, they could live to die another day. Some of the pilots even faked engine trouble to stay alive, but in the end, they hated themselves so much for doing so, that on the next mission, they did their “duty” to their emperor. Amazing, isn’t it?

Probably because of the smaller cost of the materials and the ease of transporting material to the site, there are many earthen dams today. I suppose they were properly packed down, and with the addition of vegetation, they seem to hold up well…for the most part. The Toccoa Falls Dam (later known as the Kelly Barnes Dam) was constructed ninety miles north of Atlanta, Georgia. Toccoa is a Cherokee word meaning beautiful. The dam was built across a canyon in 1887, creating a 55-acre lake 180 feet above the Toccoa Creek.

Probably because of the smaller cost of the materials and the ease of transporting material to the site, there are many earthen dams today. I suppose they were properly packed down, and with the addition of vegetation, they seem to hold up well…for the most part. The Toccoa Falls Dam (later known as the Kelly Barnes Dam) was constructed ninety miles north of Atlanta, Georgia. Toccoa is a Cherokee word meaning beautiful. The dam was built across a canyon in 1887, creating a 55-acre lake 180 feet above the Toccoa Creek.

R A Forrest established the Christian and Missionary Alliance College along the creek below the dam in 1911. It is said that he bought the land for the campus from a banker with the only $10 dollars he had to his name, offering God’s word that he would pay the remaining $24,990 of the purchase price later. I guess that the banker either trusted Forrest’s ability to pay the  balance, or decided that a Christian college would a good gift to give, whether Forrest was ever able to pay it off or not.

balance, or decided that a Christian college would a good gift to give, whether Forrest was ever able to pay it off or not.

The Christian and Missionary Alliance College had been on the site for 66 years in 1977. On November 5, 1977, a volunteer fireman inspected the dam and found everything in order. A few hours later, in the early morning of November 6, the dam suddenly gave way. With a great roar, water thundered down the canyon and creek, approaching speeds of 120 miles per hour. Still, the residents of the college had no time to evacuate. Within minutes, the entire community was slammed by a wave of water. One woman, a mother of three daughters, managed to hang onto a roof torn from a building. The wave carried her for thousands of feet. She survived, but her three daughters, were among the 39 people who lost their lives in the flood.

The investigation that followed, cited several possible or probable causes for the disaster. The failure of the dam’s slope may have contributed to weakness in the structure, particularly in the heavy rain of the previous four days. The rain swelled Barnes Lake, which normally held 17,859,600 cubic feet of water, to an estimated 27,442,800 cubic feet of water. When the low-level spillway collapsed, it exacerbated the problem. A 1973 photo showed a 12 foot high, 30 foot wide slide had occurred on the downstream face of the dam, which may have also contributed or foreshadowed the dam failure. Basically, the dam was in poor condition and the design was poor and outdated. It was a disaster waiting to happen.

As Thanksgiving approaches, I’ve been thinking about the Wampanoag Tribe, who helped the Pilgrims survive that first winter in the new world. It was a tough winter, and both the Wampanoag Tribe and the Pilgrims lost a lot of people. Many in the Wampanoag tribe, as well as the entire Patuxet Tribe, had died of smallpox. In fact, the Pilgrims might not have made it in this new country at all if the Wampanoag Tribe hadn’t helped them. The Wampanoag had fed the colonists and saved their lives when their colony was failing in the harsh winter of 1620-1621. The name Wampanoag means People of the First Light…isn’t that beautiful? The two peoples shared their knowledge. The Wampanoag Tribe taught the Pilgrims to hunt and fish, and the Pilgrims taught the Wampanoag Tribe to plant corn and beans.

As Thanksgiving approaches, I’ve been thinking about the Wampanoag Tribe, who helped the Pilgrims survive that first winter in the new world. It was a tough winter, and both the Wampanoag Tribe and the Pilgrims lost a lot of people. Many in the Wampanoag tribe, as well as the entire Patuxet Tribe, had died of smallpox. In fact, the Pilgrims might not have made it in this new country at all if the Wampanoag Tribe hadn’t helped them. The Wampanoag had fed the colonists and saved their lives when their colony was failing in the harsh winter of 1620-1621. The name Wampanoag means People of the First Light…isn’t that beautiful? The two peoples shared their knowledge. The Wampanoag Tribe taught the Pilgrims to hunt and fish, and the Pilgrims taught the Wampanoag Tribe to plant corn and beans.

A man named Squanto, who was born about 1580 near Plymouth, Massachusetts, also known as Tisquantum, is best remembered for serving as an interpreter and guide for the Pilgrim settlers at Plymouth in the 1620s. The details about how Squanto got to Europe and back have been disputed by historians. He was a Patuxet Indian born in present-day Massachusetts, who is believed to have been captured as a young man along the Maine coast in 1605 by Captain George Weymouth, who had been commissioned by Plymouth Company owner Sir Ferdinando Gorges to explore the coast of Maine and Massachusetts, and reportedly captured Squanto, along with four Penobscots, because he thought his financial backers in Britain might want to see some Indians. Weymouth brought Squanto and the other Indians to England, where Squanto lived with Ferdinando Gorges, who taught him English and hired him to be an interpreter and guide. Now fluent in English, Squanto returned to his homeland in 1614 with English explorer John Smith, possibly acting as a guide, but was captured again by another British explorer, Thomas Hunt, and sold into slavery in Spain. Squanto escaped, lived with monks for a few years, and eventually returned to North America in 1619, only to find his entire Patuxet tribe dead from smallpox. He went to live with the nearby Wampanoags. Squanto’s life was truly not easy, but he still wanted to help others. Nevertheless, Squanto was the first person the Pilgrims met. He spoke to them in  English and acted as an interpreter and guide to the Pilgrim settlers at Plymouth during their first winter in the New World. Squanto was born in about 1580 near Plymouth, Massachusetts.

English and acted as an interpreter and guide to the Pilgrim settlers at Plymouth during their first winter in the New World. Squanto was born in about 1580 near Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Squanto’s assistance in connecting the Pilgrims with the Wampanoag Tribe was vital for the preservation of the Pilgrims. There were many reasons to be Thankful on that first Thanksgiving. They had survived the winter, and smallpox. They weren’t starving or dying of starvation. They had new friends, and they had learned new skills. It is believed that the first Thanksgiving is generally believed to have occurred between September 21 and November 9, 1621.

Now that Election Day is here, our thoughts have turned from campaign speeches, fact checking, and stressing out over the polls, to getting out and voting, and then sitting back to watch the election night coverage…unless you are so tired of the whole political process, that you just want the whole thing to be over with!! Even if you are very intent on the election, you are most likely very tired of the political process. Still, the elections are very important…especially this year.

Now that Election Day is here, our thoughts have turned from campaign speeches, fact checking, and stressing out over the polls, to getting out and voting, and then sitting back to watch the election night coverage…unless you are so tired of the whole political process, that you just want the whole thing to be over with!! Even if you are very intent on the election, you are most likely very tired of the political process. Still, the elections are very important…especially this year.

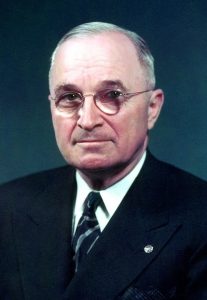

This year isn’t the only critical year we have ever had either. The November 3, 1948 Presidential election was really an important one too. President Harry S Truman was the incumbent, running against New York Governor Thomas Dewey. Truman was very much pro-Israel, and whether people realize it or not, that is important. That fact isn’t always considered important in an election, but in 1948, I believe it was, and that it made the difference. Nevertheless, many of America’s major newspapers had predicted a Dewey victory early on in the campaign cycle. A New York Times article editorialized that “if Truman is nominated, he will be forced to wage the loneliest campaign in recent history.” Maybe that was true, but it was not a deterrent. In fact, that may be the reason Truman chose not to use the press to get his message across. Truman decided in July 1948, to head out on an ambitious 22,000-mile “whistle stop” railroad and automobile campaign tour. Truman’s message was simple…”Help me keep my job as President.” As time went on, things looked worse and worse for Truman. The polls were against him. Nevertheless, the common voters warmed to his simple message, and although he was a political “underdog,” and at the end of one speech, the crowd could be heard yelling “Give ’em Hell, Harry!” It didn’t take long for the phrase to catch on and become Truman’s unofficial campaign slogan.

Then came the Chicago Tribune’s issue stating that Dewey had won the election. In reality, the Chicago Tribune severely jumped the gun. I’m sure the final outcome of the brought with it as much confusion as did the mistaken prediction of a Dewey win. Be that as it may, the “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline was a serious “egg on the face” moment for the Chicago Tribune. On Wednesday morning there was a new headline showing a picture of re-elected President Harry S Truman holding the Chicago Tribune issue that had wrongfully predicted his political downfall. In the end, Truman beat Dewey by 114 electoral votes. All I can say is beware of those early predictions.

Sometimes when a vehicle accident occurs, one or both vehicles catch on fire. It is almost to be expected periodically, but it is almost never expected to be catastrophic. Nevertheless, on November 2, 1982, such an accident occurred in the Salang Tunnel in Afghanistan, and it cost 3,000 people their lives. Most of the victims were Soviet soldiers traveling to Kabul.

Sometimes when a vehicle accident occurs, one or both vehicles catch on fire. It is almost to be expected periodically, but it is almost never expected to be catastrophic. Nevertheless, on November 2, 1982, such an accident occurred in the Salang Tunnel in Afghanistan, and it cost 3,000 people their lives. Most of the victims were Soviet soldiers traveling to Kabul.

The entrance into Afghanistan by the Soviet Union that year was disastrous in nearly every way, but possibly the worst single incident was the Salang Tunnel explosion. At the time of the crash, a long army convoy was traveling from Russia to Kabul through the border city of Hairotum. The route took the convoy through the Salang Tunnel, which is 1.7 miles long, 25 feet high and approximately 17 feet wide. The tunnel is one of the world’s highest at an altitude of 11,000 feet. It was built by the Soviets in the 1970s.

As was common in those days, the Soviet army kept a tight lid on the story. It is believed that an army vehicle  collided with a fuel truck about half way through the long tunnel. When the fuel truck exploded, about 30 buses carrying soldiers were immediately blown up. Fire in the tunnel spread quickly and the survivors of the blast began to panic. The ensuing chaos made the military stationed at the ends of the tunnel believe the explosion was part of an attack. As per protocol for terrorist attacks, the military stationed at both ends of the tunnel stopped traffic from exiting. If the fire wasn’t enough, the idling cars in the tunnel caused the levels of carbon monoxide in the air to increase drastically, The fire continued to spread as well. Exacerbating the situation, the tunnel’s ventilation system had broken down a couple of days earlier, resulting in further casualties from burns and carbon monoxide poisoning.

collided with a fuel truck about half way through the long tunnel. When the fuel truck exploded, about 30 buses carrying soldiers were immediately blown up. Fire in the tunnel spread quickly and the survivors of the blast began to panic. The ensuing chaos made the military stationed at the ends of the tunnel believe the explosion was part of an attack. As per protocol for terrorist attacks, the military stationed at both ends of the tunnel stopped traffic from exiting. If the fire wasn’t enough, the idling cars in the tunnel caused the levels of carbon monoxide in the air to increase drastically, The fire continued to spread as well. Exacerbating the situation, the tunnel’s ventilation system had broken down a couple of days earlier, resulting in further casualties from burns and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Rescue and recovery was slow due to the lack of safe working conditions for rescue crews. It took several days for workers to reach all the bodies in the tunnel. To make matters worse, the Soviet army limited the  information released about the disaster, so we may never know the full extent of the tragedy. While the fire and carbon monoxide poisonings were tragic in and of themselves, the fact that the military thought the accident might be a terrorist attack, really caused the massive amounts of death. The people in the tunnel were trapped, and there was no ventilation. They couldn’t get away from the death enveloping them on all sides. I’m sure there was panic and screaming, making the chaos even worse. The very thought of all those people trapped in that tunnel makes me feel nauseous, and I’m sure that if the Soviets kept it under wraps, there were families who never knew what happened to their loved ones.

information released about the disaster, so we may never know the full extent of the tragedy. While the fire and carbon monoxide poisonings were tragic in and of themselves, the fact that the military thought the accident might be a terrorist attack, really caused the massive amounts of death. The people in the tunnel were trapped, and there was no ventilation. They couldn’t get away from the death enveloping them on all sides. I’m sure there was panic and screaming, making the chaos even worse. The very thought of all those people trapped in that tunnel makes me feel nauseous, and I’m sure that if the Soviets kept it under wraps, there were families who never knew what happened to their loved ones.

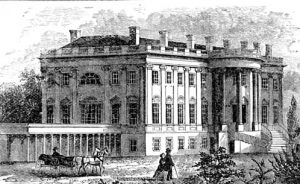

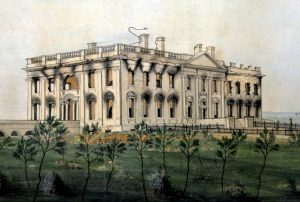

It was a long time coming. An actual house for the President of the United States was a long time coming. Prior to establishing the nation’s capital in Washington DC, the United States Congress and its predecessors had met in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and Congress Hall), New York City (Federal Hall), and a number of other locations (York, Pennsylvania; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Maryland State House in Annapolis, Maryland; and Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey). Then, it was decided that our government needed a permanent home. Washington DC was selected.

It was a long time coming. An actual house for the President of the United States was a long time coming. Prior to establishing the nation’s capital in Washington DC, the United States Congress and its predecessors had met in Philadelphia (Independence Hall and Congress Hall), New York City (Federal Hall), and a number of other locations (York, Pennsylvania; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Maryland State House in Annapolis, Maryland; and Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey). Then, it was decided that our government needed a permanent home. Washington DC was selected.

The first president who would have an actual government-owned home in Washington DC was President John Adams, and he would only live there for the last year of his only term in office. President John Adams, in the last year of his only term as president, moved into the newly constructed President’s House on November 1, 1800. The President’s House was the original name for what is known today as the White House. Adams and his wife had been living in temporarily at Tunnicliffe’s City Hotel near the half-finished Capitol building since June 1800, when the federal government  was moved from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington DC. When Adams first arrived in Washington, he wrote to his wife Abigail, who was still at their home in Quincy, Massachusetts, that he was pleased with the new site for the federal government and that he had explored the soon-to-be President’s House and liked it.

was moved from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington DC. When Adams first arrived in Washington, he wrote to his wife Abigail, who was still at their home in Quincy, Massachusetts, that he was pleased with the new site for the federal government and that he had explored the soon-to-be President’s House and liked it.

Although workmen had rushed to finish plastering and painting walls before Adams returned to DC from a visit to Quincy in late October, the construction was still unfinished when Adams rolled up in his carriage on November 1. However, the furniture from their Philadelphia home was in place and a portrait of George Washington was already hanging in one room. It was a decent start. The next day, Adams sent a note to Abigail, who would arrive in Washington later that month, saying that he hoped “none but honest and wise men [shall] ever rule under this roof.” I wish that  had always been the case, and of course the idea of good and bad presidents are often a matter of opinion.

had always been the case, and of course the idea of good and bad presidents are often a matter of opinion.

The President’s House though new had its issues. Adams was initially very pleased with the presidential mansion, but he and Abigail found it to be cold and damp during the winter. Abigail wrote to a friend saying that the building was tolerable only so long as fires were lit in every room. She also said that on a funny note, she also said that she had to hang their washing in an empty “audience room,” which is the current East Room. Now, that’s quite a thought. During the War of 1812, the White House was set on fire by the British, and had to be repaired.

Anyone who finds Winter and the shortened nights depressing, can understand how a person can crave the sun. There is even a condition known as SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) that comes out of the limited or even lack of sunlight. People in Alaska and other areas near the pole regions often suffer from it in the dark winter days. The polar regions aren’t the only ones with the problem, however.

Anyone who finds Winter and the shortened nights depressing, can understand how a person can crave the sun. There is even a condition known as SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) that comes out of the limited or even lack of sunlight. People in Alaska and other areas near the pole regions often suffer from it in the dark winter days. The polar regions aren’t the only ones with the problem, however.

There is a tiny town in Norway, called Rjukan. For hundreds of years, the inhabitants of this tiny Norwegian town went without direct sunlight for almost half the year. It’s not because this town is situated near the North Pole, because it isn’t. Nevertheless, the place Rjukan is situated is the problem. Rjukan is wedged at the bottom of a steep east-west valley in southern Norway’s Telemark region. It’s surrounded by mountains, including the 6,178-foot-high Gaustatoppen.

Rjukan is a company town, founded for the employees of Norsk Hydro, an aluminum powerhouse that is still going strong today. At first the town built an aerial tramway, Krossobanen, to give employees and their families access to the winter sunshine. Sam Eyde, the founder of the town, began to consider building sun mirrors on the mountain as far back as 1913, but the tramway was built first. It was the first such system in northern Europe, and still functions today. The tramway served a purpose, but really didn’t solve the problem.

Still, the desire for the kind of direct sunlight first shared by Eyde never went away. Then, more than 90 years later, a local resident and artist, Martin Andersen took up the idea from the history books. He began to think that maybe the idea was a good one. So, on October 30, 2013, almost 100 years to the day when the idea was first presented, the Rjukan sun mirror officially opened. For the first time in the town’s history, the sun actually shown on the town in the winter months. The people were elated. At first, not everyone was on board with Andersen’s plans. Many locals criticized the $750,000 project, believing the money could be better spent elsewhere, but when they saw how excited everyone was with the day, it was hard to continue to be negative. The people put on sunglasses, and basked in the sun’s light and warmth. It was like a big party. The sun mirrors continue to be a big hit in the town, oddly in the summer, as well as the winter.

Local residents now enjoy an approximately 6,500 square foot ellipse-shaped beam of sunlight into the town square. Between 80% and 100% of the sun’s light is transferred down into the town. The mirror system has helped the tourism industry. It’s said, “This summer there were several tourists who turned their backs on the real sun, and sat instead with their faces to the sun mirror.” Locals and tourists can even hike to the mirrors. As  unusual as it may seem, Rjukan’s sun mirror system is not a world first. The small town of Viganella, in Italy’s steep Antrona Valley, celebrated its own day of the light in December 2006, as a sheet of steel was installed to reflect sunlight into the town square from November to February. The system in Rjukan is significantly more advanced, however. Each of the three 182 square foot mirrors are controlled computer-driven motors called heliostats. They track the movement of the sun across the horizon and constantly reposition the mirrors to keep the reflected light as consistent as possible. What a cool idea for a town and its people who can’t get easy access to the sun.

unusual as it may seem, Rjukan’s sun mirror system is not a world first. The small town of Viganella, in Italy’s steep Antrona Valley, celebrated its own day of the light in December 2006, as a sheet of steel was installed to reflect sunlight into the town square from November to February. The system in Rjukan is significantly more advanced, however. Each of the three 182 square foot mirrors are controlled computer-driven motors called heliostats. They track the movement of the sun across the horizon and constantly reposition the mirrors to keep the reflected light as consistent as possible. What a cool idea for a town and its people who can’t get easy access to the sun.

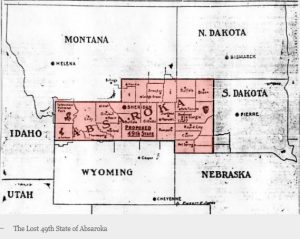

Absaroka…have you ever heard of it? No…I hadn’t either, but it was of some importance to the United States, and it would have been of some significance to me and my family had it not been a temporary situation. You see, when President Franklin D Roosevelt put “The New Deal” in place, there were a lot of people who didn’t think it was such a good deal…much like “The Green New Deal” of today. “The New Deal” was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. The idea was to “help” by responding to needs for relief, reform, and recovery from the Great Depression. The plan created major federal programs and agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). They provided support for farmers, the unemployed, youth, and the elderly. The New Deal included new constraints and safeguards on the banking industry and efforts to re-inflate the economy after prices had fallen sharply. The New Deal programs included both laws passed by Congress, as well as presidential executive orders during the first term of the presidency of Roosevelt.

Absaroka…have you ever heard of it? No…I hadn’t either, but it was of some importance to the United States, and it would have been of some significance to me and my family had it not been a temporary situation. You see, when President Franklin D Roosevelt put “The New Deal” in place, there were a lot of people who didn’t think it was such a good deal…much like “The Green New Deal” of today. “The New Deal” was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. The idea was to “help” by responding to needs for relief, reform, and recovery from the Great Depression. The plan created major federal programs and agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). They provided support for farmers, the unemployed, youth, and the elderly. The New Deal included new constraints and safeguards on the banking industry and efforts to re-inflate the economy after prices had fallen sharply. The New Deal programs included both laws passed by Congress, as well as presidential executive orders during the first term of the presidency of Roosevelt.

The New Deal failed because Roosevelt misunderstood the cause of the Great Depression. When a doctor misdiagnoses the symptoms that present themselves, the doctor cannot prescribe the right medicine to cure the disease of a patient. Similarly, Roosevelt prescribed “The New Deal” to cure the economy of the United States from the Great Depression. Roosevelt’s “medicine” did not work because his administration failed to recognize the true causes of the Great Depression and therefore prescribed the wrong medicine. Roosevelt assumed that the free market, and not the government caused the Great Depression. Roosevelt believed the Great Depression was partly caused by poor investments and stock manipulations by rich people. To complicate matters, he blamed the Great Depression on bankers, speculators, and journalists. In reality, the causes of the Great Depression boiled down to three major causes…which explain why there was a banking crisis, why the  stock market declined, why exports vanished, why trading partners were upset, why major industries collapsed, and why there was uncertainty on the administration’s policies. These three explanations of the causes contrast with Roosevelt’s assumption that the private, not the public sector caused the problem. First, the negative consequences of World War I, increasing debt from less than $2 billion to over $20 billion, while at the same time, US loans to Europe amounted to over $10 billion. Second, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act…the highest tariff in US history, which affected over 3,000 imported items and even increased taxes on some items. As a result of those high tariffs, foreign goods became less competitive and similar domestic goods more competitive. Third, the Federal Reserve did not prevent a banking crisis, but rather helped cause one. It was argued that the economic contraction was exacerbated because of the bank failures and the massive withdrawals of currency from the financial system while the Federal Reserve did not provide the necessary liquidity that the system required.

stock market declined, why exports vanished, why trading partners were upset, why major industries collapsed, and why there was uncertainty on the administration’s policies. These three explanations of the causes contrast with Roosevelt’s assumption that the private, not the public sector caused the problem. First, the negative consequences of World War I, increasing debt from less than $2 billion to over $20 billion, while at the same time, US loans to Europe amounted to over $10 billion. Second, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act…the highest tariff in US history, which affected over 3,000 imported items and even increased taxes on some items. As a result of those high tariffs, foreign goods became less competitive and similar domestic goods more competitive. Third, the Federal Reserve did not prevent a banking crisis, but rather helped cause one. It was argued that the economic contraction was exacerbated because of the bank failures and the massive withdrawals of currency from the financial system while the Federal Reserve did not provide the necessary liquidity that the system required.

As people became more and more agitated about the unsuccessful New Deal, an idea began to form…secession. One of the leaders of the secessionist movement was A R Swickard, the street commissioner of Sheridan, Wyoming, who appointed himself “governor” and started hearing grievances in the “capital” of Sheridan. The new state was to be called Absaroka, which means “children of the large-beaked bird.” They planned secession in 1939. This region largely belongs to the Crow people and the Sioux, according to the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851). Absaroka is also the namesake of the Absaroka mountain range. The area involved was the entire northern part of Wyoming, the western part of South Dakota, including the Black Hills, and the southeastern corner of Montana. Increasing tourism to the region was a motivation for the proposed state because Mount Rushmore (constructed 1927–1941) would be within Absaroka according to some plans.

The region’s complaints came from ranchers and independent farmers in remote parts of the three states, who  resented the New Deal and Democratic control of state governments, especially the government of Wyoming. In preparation for state secession, state automobile license plates bearing the name were distributed, as well as pictures of Miss Absaroka 1939. The movement was unsuccessful and fairly short-lived. The chief record of its existence comes from the Federal Writers’ Project, which included a story about the plan as an example of Western eccentricity. Oh those eccentric Westerners!! Imagine wanting to limit government, high taxes, and strict laws and mandates!! What were they thinking? Freedom, limited government, capitalism vs socialism…yep among other things, that’s what they were thinking.

resented the New Deal and Democratic control of state governments, especially the government of Wyoming. In preparation for state secession, state automobile license plates bearing the name were distributed, as well as pictures of Miss Absaroka 1939. The movement was unsuccessful and fairly short-lived. The chief record of its existence comes from the Federal Writers’ Project, which included a story about the plan as an example of Western eccentricity. Oh those eccentric Westerners!! Imagine wanting to limit government, high taxes, and strict laws and mandates!! What were they thinking? Freedom, limited government, capitalism vs socialism…yep among other things, that’s what they were thinking.

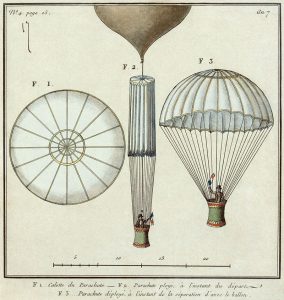

Jumping out of a perfectly good airplane…known by most of us as a parachute jump…is something that the majority of us would probably not do. Still, there are many people that love to jump, and others who would love to try it. I would have thought that this was a rather new hobby, and a even fairly new way to fight fires or fight wars, but I would be wrong. The first parachute jump is said to have taken place in 1797…yes, I said 1797!! How could that be? There weren’t even any planes?

Jumping out of a perfectly good airplane…known by most of us as a parachute jump…is something that the majority of us would probably not do. Still, there are many people that love to jump, and others who would love to try it. I would have thought that this was a rather new hobby, and a even fairly new way to fight fires or fight wars, but I would be wrong. The first parachute jump is said to have taken place in 1797…yes, I said 1797!! How could that be? There weren’t even any planes?

That first parachute jumper was André-Jacques Garnerin from a hydrogen balloon 3,200 feet above Paris. Military jumpers jump at altitudes between 15,000 feet and 35,000 feet…which seems a bit high to me, but what do I know. The lowest altitude to jump is an almost suicidal 100 feet. That put Garnerin’s jump on the low end of the safe spectrum. Garnerin first came up with the idea of using air resistance to slow an individual’s fall from a high altitude while he was a prisoner during the French Revolution. Although he never employed a parachute to escape from the high ramparts of the Hungarian prison where he spent three years, Garnerin never lost interest in the concept of the parachute. He thought that given enough height, he could have escaped from that prison.

After he was released, he continued to experiment with the idea. Then in 1797, he completed his first parachute. The parachute consisted of a canopy 23 feet in diameter, attached to a basket with suspension lines. He was finally ready. On October 22, 1797, Garnerin attached the parachute to a hydrogen balloon and  ascended to an altitude of 3,200 feet. He then climbed into the basket and cut the parachute loose from the balloon. To say it was a perfect trial, would be an epic mistake. Garnerin had failed to include an air vent at the top of the prototype, and he oscillated wildly in his descent. Nevertheless, he landed shaken but unhurt half a mile from the balloon’s takeoff site. Unless you are an expert on parachutes, or even an amateur, you probably wouldn’t know about the vent hole. Nevertheless, it is quite important. I would expect that Garnerin’s wife would have been ready to choke him for trying something so crazy, but I would be wrong. In 1799, Garnerin’s wife, Jeanne-Genevieve, became the first female parachutist. I guess he married a woman who was as much an adventurist as he was. They continued on with their work, and in 1802, Garnerin made a spectacular jump from 8,000 feet during an exhibition in England. Unfortunately, he died in a balloon accident on August 18, 1823 while preparing to test a new parachute.

ascended to an altitude of 3,200 feet. He then climbed into the basket and cut the parachute loose from the balloon. To say it was a perfect trial, would be an epic mistake. Garnerin had failed to include an air vent at the top of the prototype, and he oscillated wildly in his descent. Nevertheless, he landed shaken but unhurt half a mile from the balloon’s takeoff site. Unless you are an expert on parachutes, or even an amateur, you probably wouldn’t know about the vent hole. Nevertheless, it is quite important. I would expect that Garnerin’s wife would have been ready to choke him for trying something so crazy, but I would be wrong. In 1799, Garnerin’s wife, Jeanne-Genevieve, became the first female parachutist. I guess he married a woman who was as much an adventurist as he was. They continued on with their work, and in 1802, Garnerin made a spectacular jump from 8,000 feet during an exhibition in England. Unfortunately, he died in a balloon accident on August 18, 1823 while preparing to test a new parachute.

Most airplanes in the 1940s were of a similar design…the kind that were a simple wing design. There was, however, a futuristic flying machine that made it’s debut on October 21, 1947. The Northrup YB-49 Flying Wing was a prototype jet-powered heavy bomber developed by Northrop Corporation shortly after World War II for service with the United States Air Force. The YB-49 featured a futuristic flying wing design and was a turbojet-powered version of the earlier, piston-engined Northrop XB-35 and YB-35. The test flight of the Northrop YB-49 took place at Northrop Field, Hawthorne, California. It was piloted by Chief Test Pilot Max R Stanley. That first flight seemed to be going well, but it faced stability problems during simulated bomb runs and political problems doomed the flying wing.

Most airplanes in the 1940s were of a similar design…the kind that were a simple wing design. There was, however, a futuristic flying machine that made it’s debut on October 21, 1947. The Northrup YB-49 Flying Wing was a prototype jet-powered heavy bomber developed by Northrop Corporation shortly after World War II for service with the United States Air Force. The YB-49 featured a futuristic flying wing design and was a turbojet-powered version of the earlier, piston-engined Northrop XB-35 and YB-35. The test flight of the Northrop YB-49 took place at Northrop Field, Hawthorne, California. It was piloted by Chief Test Pilot Max R Stanley. That first flight seemed to be going well, but it faced stability problems during simulated bomb runs and political problems doomed the flying wing.

The unusual configuration, for an aircraft of that time, had no fuselage or tail control surfaces. The crew compartment, engines, fuel, landing gear, and armament were contained within the wing. Air intakes for the turbojet engines were placed in the leading edge and the exhaust nozzles were at the trailing edge. Four small vertical fins for improved yaw stability were also at the trailing edge. While the design might have had many stabilizing characteristics, it was still basically a set of wings, connected together, with a small crew  compartment in the middle. I suppose it looked like an early version of the F-117 Nighthawk stealth airplane, but with much bigger wings and a much smaller crew cabin.

compartment in the middle. I suppose it looked like an early version of the F-117 Nighthawk stealth airplane, but with much bigger wings and a much smaller crew cabin.

The YB-49 was powered by eight General Electric, Allison Engine Company, J35-A-5 engines. A variant of that engine was used in the North American Aviation XP-86, replacing its original Chevrolet-built J35-C-3. The engines were later upgraded to J35-A-15s. The J35 was a single-spool, axial-flow turbojet engine with an 11-stage compressor and single-stage turbine. It shocks me that there was such a thing as a turbojet engine back then, but apparently there was. During the testing of the YB-49, it reached a maximum speed of 428 knots (493 miles per hour) at 20,800 feet. It had a cruising speed of 365 knots (429 miles per hour). The airplane had a service ceiling of 49,700 feet. The YB-49 had a maximum fuel capacity of 14,542 gallons of JP-1 jet fuel. Its combat radius was 1,403 nautical miles. The maximum bomb load of the YB-49 was 16,000 pounds, though the actual number of bombs was limited by the volume of the bomb bay and the capacity of each bomb type. While the YB-35 Flying Wing was planned for multiple machine gun turrets, but none were attached.

In the second test flight, the unstable YB-49 crashed on Jan. 13, 1948. After the crash, the testing continued with both aircraft until the second YB-49 crashed on June 5, 1948. They tried to make the plane work, but it just didn’t seem to be in the cards. The crew of the crashed YB-49 included Major Daniel H Forbes Jr, pilot; Captain Glen W Edwards, copilot; Lieutenant Edward L Swindell, flight engineer; Clare E Lesser and C C La Fountain. Later, The two pilots were honored with the naming of two Air Force installations. Edwards Air Force Base, California, was named in honor of Captain Edwards, and Forbes Air Force Base, Kansas, was named in honor of Major Forbes.

In the second test flight, the unstable YB-49 crashed on Jan. 13, 1948. After the crash, the testing continued with both aircraft until the second YB-49 crashed on June 5, 1948. They tried to make the plane work, but it just didn’t seem to be in the cards. The crew of the crashed YB-49 included Major Daniel H Forbes Jr, pilot; Captain Glen W Edwards, copilot; Lieutenant Edward L Swindell, flight engineer; Clare E Lesser and C C La Fountain. Later, The two pilots were honored with the naming of two Air Force installations. Edwards Air Force Base, California, was named in honor of Captain Edwards, and Forbes Air Force Base, Kansas, was named in honor of Major Forbes.