History

Different portions of an Austrian army, were scouting for forces of the Ottoman Empire, when they came across a band of gypsies near Karansebes…a small town in modern-day Romania. The gypsies were had been sitting around enjoying schnapps. The soldiers bought out their entire supply, and proceeded to get drunk. Now, as we all know, liquor is legendary for causing stupid fights, but this was about to become the most stupid fight of them all. On that September 19, 1788 night, the group of Austrian cavalrymen were in the woods looking for the enemy…Turkish forces in the area of Karansebes.

Different portions of an Austrian army, were scouting for forces of the Ottoman Empire, when they came across a band of gypsies near Karansebes…a small town in modern-day Romania. The gypsies were had been sitting around enjoying schnapps. The soldiers bought out their entire supply, and proceeded to get drunk. Now, as we all know, liquor is legendary for causing stupid fights, but this was about to become the most stupid fight of them all. On that September 19, 1788 night, the group of Austrian cavalrymen were in the woods looking for the enemy…Turkish forces in the area of Karansebes.

After buying the schnapps the soldiers began their booze-fest. A few hours later, which would be an eternity in “drunk time.” As we all know, that means they were very drunk. At this point, another group of foot soldiers came along and wanted to join the booze-fest. But the cavalrymen refused to share. Then they decided to build a makeshift wall around their booze…not the best idea. The second group of soldiers got angry and things gt heated. Before long the groups were fighting. The soldiers who had joined them tried to fool the cavalry into retreating, by telling them they saw Turkish soldiers. That plan backfired as everyone…soldier and cavalry alike…turned the violent stampede back towards camp.

As the Austrian officers tried to calm the men, the army’s mixed forces of Italians, Slovaks, and Hungarians, all of whom didn’t speak German very well, would have none of it. As they tried yelling stop…which is “Halt!” in German, the Italians, Slovaks, and Hungarians thought they were saying, “Allah!” which only intensified the brutal, confused madness. The rest of the camp woke up, and had no idea what was going on, so 100,000 men, who thought they heard a battle going on, they assumed they were under attack by Ottoman forces. They immediately jumped into combat and things got so out of hand, that the army literally brought out the big guns, fighting against their own men. The resulting confusion caused a great mix-up in the regiments, who became so terrified, literally of themselves, that they abandoned Karansebes altogether. The troops razed and pillaged towns for nearly 30 miles before the army recollected itself under new leadership.

Two days after the battle, the Ottoman Empire troops finally arrived at Karansebes to find 10,000 dead and wounded Austrian soldiers. The Ottoman troops couldn’t believe their eyes. Their battle had already been won. The Austrian army, as well as the Italians, Slovaks, and Hungarians had handed the victory to the Ottomans, by almost entirely taking our their own people. The Ottoman troops laughed at their foolish enemies, after which they executed the survivors, and took the city without a fight. Chaos really never brings good results, and often in a riot situation, the very people they are supposedly trying to save are the ones who are hurt by the riots, often losing their own lives.

On September 11th, I wrote about the significance if the September 11th date and the terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon, but there was another target that day. The attack on Washington DC was at first thought to be planned for the White House, but it was later determined that the attack was planned for the nation’s capitol building. I have wondered if that September 11th date could have a significance for the capitol too, so I did some research. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a specific day that the groundbreaking at the capital took place.

On September 11th, I wrote about the significance if the September 11th date and the terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon, but there was another target that day. The attack on Washington DC was at first thought to be planned for the White House, but it was later determined that the attack was planned for the nation’s capitol building. I have wondered if that September 11th date could have a significance for the capitol too, so I did some research. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a specific day that the groundbreaking at the capital took place.

I did find out that on September 18, 1793, George Washington laid the cornerstone to the United States Capitol building. Now, I’m not a contractor, but it makes sense to me that from groundbreaking to cornerstone, could logically take a week…putting the possible groundbreaking on…you guessed it, September 11, 1793. The building itself would take nearly a century to complete, as architects came and went, the British set fire to it, and it was called into use during the Civil War. Nevertheless, the original groundbreaking took place before September 18, 1793. Today, the Capitol building, with its famous cast-iron dome and important collection of American art, is part of the Capitol Complex, which includes six Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings, all developed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

As we all know, the brave heroes of Flight 93 foiled that attack on September 11, 2001, which is why the US Capitol building was not destroyed or damaged. Those people saved the capitol building and somehow managed t crash their plane into a field…hitting no one on the ground. They knew that the other planes that had been hijacked, were not landing to have their demands met…they were being flown into buildings, and that meant that they were likely headed for the same fate. They knew that all they could do was to sacrifice their own lives to make sure that this attack did not succeed, and that is what they did, crashing it into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. With a quick, “Let’s roll!!” they ran forward and fought with the terrorists, and while they weren’t able to get complete control of the plane, they made sure it didn’t reach it’s intended destination, and they saved the capital.

I can’t say, for sure, that September 11th was the date that they broke ground on the capital building, but in

my mind, it makes sense that it was. And that makes it shocking to me. There were some days in Islamic history about September 11, but they were simply battles and such that took place, not the day that a city or place that was being attacked…also being the day that it was founded or had it’s groundbreaking. That makes it monumental, but in the third attack, they weren’t successful, and the plane crashed in a field. Maybe that was monumental too.

my mind, it makes sense that it was. And that makes it shocking to me. There were some days in Islamic history about September 11, but they were simply battles and such that took place, not the day that a city or place that was being attacked…also being the day that it was founded or had it’s groundbreaking. That makes it monumental, but in the third attack, they weren’t successful, and the plane crashed in a field. Maybe that was monumental too.

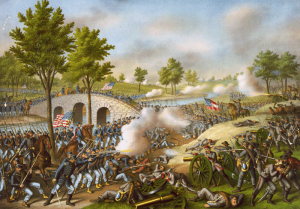

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

These days, with the many types of bombs nations use for warfare, it would be easy to annihilate an entire town, but during the Civil War…not so much. One bomb dropped on Hiroshima instantly killed 80,000 people. Of course that was on August 6, 1945, and not 1862. September 17, 1862 dawned slowly through the fog. It seemed like the start of a peacefully beautiful day, but looks can be deceiving. That morning, the soldiers were busy, trying to wipe away the dampness, when cannons began to roar and sheets of flame burst forth from hundreds of rifles. The bloodiest one-day battle in American History had begun. The Battle of Antietam was a 12-hour battle that swept across the rolling farm fields in western Maryland. It was this battle between North and South that changed the course of the Civil War, helped free over four million Americans, devastated Sharpsburg, and no other one-day battle would be as bloody.

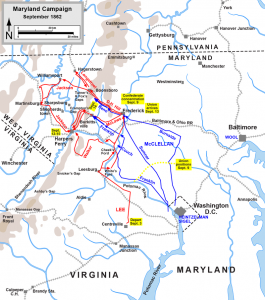

The Battle of Antietam marked the first invasion into the North by Confederate General Robert E Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. It was the culmination of the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Southern armies were also advancing in Kentucky and Missouri, as the tide of war flowed north. After Lee’s dramatic victory at the Second Battle of Manassas during the last two days of August, he wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that “we cannot afford to be idle.” Lee wanted to keep the pressure on in order to secure Southern independence through victory in the North; influence the Fall mid-term elections; obtain much-needed supplies; move the war out of Virginia, possibly into Pennsylvania; and to liberate Maryland, a Union state, but a slave-holding border state divided in its values.

Lee’s army splashed across the Potomac River and arrived in Frederick, Virginia, where he boldly divided his army to capture the Union garrison stationed at Harpers Ferry. A vital location on the Confederate lines of supply and communication back to Virginia; Harpers Ferry, Maryland was the gateway to the Shenandoah Valley. Lee’s link to the south was threatened by the 12,000 Union soldiers at Harpers Ferry. General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson and about half of the Army of Northern Virginia were sent to capture Harpers Ferry. The rest of the Confederates moved north and west toward South Mountain and Hagerstown, Maryland. The Confederate army soon retreated from South Mountain, and Lee considered returning to Virginia. However, with Jackson’s capture of Harpers Ferry on September 15th, Lee decided to make a stand at Sharpsburg.

Lee gathered his forces on the high ground west of Antietam Creek, with General James Longstreet’s command holding the center and the right, while Jackson’s men filled in on the left. The Confederate position was strengthened with the mobility provided by the Hagerstown Turnpike that ran north and south along Lee’s line. Still, the Potomac River behind them and only one crossing back to Virginia remained a risk. Lee and his men watched the Union army gather on the east side of Antietam Creek. Thousands of soldiers in blue marched into position throughout September 15th and 16th as General McClellan prepared for his attempt to drive Lee from Maryland. McClellan’s plan was to “attack the enemy’s left” and when “matters looked favorably,” attack the Confederate right, and “whenever either of those flank movements should be successful to advance our center.” As the opposing forces moved into position during the rainy night of September 16th, one Pennsylvanian remembered, “…all realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead.”

The twelve-hour battle began at dawn, and for the next seven hours, there were three major Union attacks on the Confederate left, moving from north to south. General Joseph Hooker’s command led the first Union assault. General Joseph Mansfield’s soldiers attacked second, followed by General Edwin Sumner’s men as McClellan’s plan broke down into a series of uncoordinated Union advances. The fierce battle raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, West Woods, and the Sunken Road as Lee shifted his men to withstand each of the Union thrusts. After clashing for over eight hours, Lee’s troops were pushed back, but not broken. Shockingly, over 15,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.

While the Union assaults were being made on the Sunken Road, a mile-and-a-half farther south, Union General Ambrose Burnside opened the attack on the Confederate right. He first sought to capture the bridge that would later bear his name, but a small Confederate force, positioned on higher ground, was able to delay Burnside for three hours. Finally, about 1:00pm Burnside captured the bridge, and then reorganized for two hours before moving forward across the difficult terrain…an unfortunate delay. When the advance did begin, it was turned back by Confederate General AP Hill’s reinforcements, who had arrived in the late afternoon from Harpers Ferry.

Neither flank of the Confederate army collapsed far enough for McClellan to advance his center attack, leaving a sizable Union force that never entered the battle. Despite an estimated 23,100 casualties of the nearly 100,000 engaged, both armies stubbornly held their ground as the sun set on the devastated landscape. The next day, September 18, 1862, the opposing armies gathered their wounded and buried their dead. That night  General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

General Robert E Lee’s army withdrew back across the Potomac River to Virginia, ending his first invasion into the North. Lee’s retreat to Virginia provided President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Now, the Civil War had a dual purpose of preserving the Union and ending slavery, which the United States had been trying to end since it was founded.

The Battle of Antietam was fought over an area of 12 square miles. Today the site consists of 184 acres containing approximately 5 miles of paved avenues. Located along the battlefield avenues to mark battle positions of infantry, artillery, and cavalry are many monuments, markers, and narrative tablets. Markers describe the actions at Turner’s Gap, Harpers Ferry, and Blackford’s Ford. Key artillery positions on the field of Antietam are marked by cannon. And 10 large-scale field exhibits at important points on the field indicate troop positions and battle action.

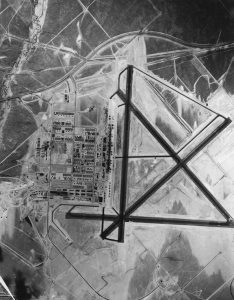

Prior to December 7, 1941, the United States had signed a Proclamation of Neutrality. They did not want to get pulled into World War II, any more than they had World War I and any of the other wars they were involved in. Still, I think everyone knew that it was inevitable…even before the Japanese attack. Early on the Sunday morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and almost simultaneously at other locations in the Pacific, would end any continued semblance of neutrality, and the United States prepared for war. The response to the attack was quick and decisive. The US Army Air Force (USAAF), under the command of Major General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold was authorized to equip, man, and train itself into the world’s most powerful air force, and to do so quickly. The first order of business was to establish air force bases. By early 1942, the USAAF had committed to building scores of air bases across the United States. Everyone wanted to help, so a Chamber of Commerce delegation from Casper, Wyoming, traveled to Washington DC, to lobby for one of the proposed air bases. According to Joye Kading, longtime secretary at the Casper Army Air Base, they marketed the “zephyr wind” that whips around the western end of Casper Mountain as part of what made it a perfect location. The USAAF agreed.

Prior to December 7, 1941, the United States had signed a Proclamation of Neutrality. They did not want to get pulled into World War II, any more than they had World War I and any of the other wars they were involved in. Still, I think everyone knew that it was inevitable…even before the Japanese attack. Early on the Sunday morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and almost simultaneously at other locations in the Pacific, would end any continued semblance of neutrality, and the United States prepared for war. The response to the attack was quick and decisive. The US Army Air Force (USAAF), under the command of Major General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold was authorized to equip, man, and train itself into the world’s most powerful air force, and to do so quickly. The first order of business was to establish air force bases. By early 1942, the USAAF had committed to building scores of air bases across the United States. Everyone wanted to help, so a Chamber of Commerce delegation from Casper, Wyoming, traveled to Washington DC, to lobby for one of the proposed air bases. According to Joye Kading, longtime secretary at the Casper Army Air Base, they marketed the “zephyr wind” that whips around the western end of Casper Mountain as part of what made it a perfect location. The USAAF agreed.

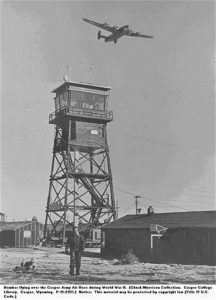

In March 1942, the US Army Corps of Engineers leased the old Casper City Hall at Center and Eighth streets in downtown Casper, in preparation for the construction of the new Army Air Base at Casper. The site they selected was a high, flat, sagebrush-covered terrace located nine miles west of town on US Highway 20-26 and adjacent to the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy railroad. After the war, the site became the Natrona County Municipal Airport and the land and all buildings became county property…later the name was changed to Casper-Natrona County International Airport when the airport achieved international status. The Casper Air Base was built in record time. Ground was broken in April, and six months later, on September 1, 1942, the base was officially opened. B-17 bomber crews began their Combat Crew Training School at the facility that consisted of four mile-long runways and around 400 buildings. With in six months, in the spring of 1943, the base transitioned from B-17 to B-24 crew training. Kading said, “The base was built to accommodate 20,000 men to be trained. They would come out there, and they were trained to do the last of their training in the B-17s and the B-24s because they could go around the east end of Casper Mountain and hit the zephyrs…our famous west winds…to take them right up to the sky.” By war’s end, almost 18,000 men had been trained at the Casper Army Air Base.

Not all was fun and games in learning to fly. Pilots did face risks too, as they gained experience. Flying over mountains can bring downdrafts, and turbulence, and it can make for a risky flight for the inexperienced pilot. The base had it’s share of accidents. Kading said, “The fellows hit something in the wind that they didn’t know how to handle, and they would have a plane wreck and they were lost. A lot of our pilots were in training, and we had some of our planes [that] were wrecked in other states. The soldiers’ bodies were then shipped back home to their families.” In the war years, the base was almost a third of the size of the city that was it’s host. On any given day, the base had an average of approximately 2,250 Army Air Force personnel and 800 civilians. I’m told by my Aunt Sandy Pattan that some of my aunts were among the civilians who worked there. The training class sizes varied, with as many as 6,000 in training during peak times. The men arrived in Casper by train, in newly assembled crews, each consisting of two pilots, a navigator, a bombardier, a radioman, flight engineer, and four gunners, to begin a strict regimen of training.

In one record-setting month, crews flew more than 7,500 hours at Casper Army Air Base. The remains of these activities are scattered across the high plains of Wyoming in the form of spent .50-caliber bullets, shells and links, 100-pound practice bomb fragments, and the wreckage of more than 70 aircraft. At the height of training, more than one million .50-caliber rounds and one thousand 100-pound training bombs would be expended per month. Now that, for some reason, amazes me. To think of spent bullets and parts of bombs or planes just lying around in the plains of Wyoming…just amazing, but of course, logical. One hundred forty Casper Army Air Base aviators perished in 90 plane crashes in training. Many more died later in combat. One hundred forty Casper Army Air Base aviators perished in 90 plane crashes between September 1942 and March 1945. Most of the crashes were in Wyoming, but many occurred out of state when the fliers were on longer training flights.

Most of the soldiers who came to Casper were not from Wyoming, but they embraced Wyoming and felt like their time in Casper was very special. Not only did Casper Army Air Base become a part of them forever, but they became a part of it too. Some of the soldiers wanted to show just how special the base was to them, so they decided to paint murals at the enlisted men’s club. Casper artist and art historian, Eric Wimmer, later researched the series of murals that depicted Wyoming’s history, and found that they were painted by some of the soldiers. Wimmer said, “They served for a short time, and then many soldiers were stationed at another base or sent overseas to fight in the war. This became the driving inspiration behind the concept [Cpl.] Leon Tebbetts developed for painting a set of murals in the Servicemen’s Club. He planned to give these temporary residents a history lesson on the state of Wyoming before they left.” The work began in October 1943, Tebbetts and three other soldiers with art backgrounds…JP Morgan, William Doench, and David Rosenblatt…started the series of 15 murals that included American Indians, travel on the trails in pioneer days, and other historic subjects. The murals are still there to this day.

The Casper Army Air Base closed in 1945, when the war ended. Today, the site of the old bomber base is largely intact with 90 of the original buildings still standing, including all six of the original hangars. I know that one of the barracks was moved to North Casper, because my grandfather, George Byer bought it to expand his small house to accommodate his large family of nine children. I remember playing back in that large room as a child. Visitors to the Wyoming Veterans Memorial museum in the base’s former Servicemen’s Club encounter a variety of stories: a gunnery instructor who gained his experience against the Japanese fleet during the Battle of Midway; a base commander who was known as the best machine gunner in the world; and a bomber navigator who was blown out of his B-17 and held prisoner in Germany. In addition, there are accounts of the

tragedy of the Casper Mountain bomber crash that I am certain was the crash that my then 8-year-old mother, Collene (Byer) Spencer witnessed. The base was also witness to the adventures of renowned test pilot Chuck Yeager, and saw the time that comedian Bob Hope paid a visit to the soldiers stationed there.

tragedy of the Casper Mountain bomber crash that I am certain was the crash that my then 8-year-old mother, Collene (Byer) Spencer witnessed. The base was also witness to the adventures of renowned test pilot Chuck Yeager, and saw the time that comedian Bob Hope paid a visit to the soldiers stationed there.

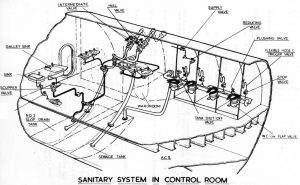

German submarine U-1206 was a Type VIIC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II. Construction started on June 12, 1943 at F. Schichau GmbH in Danzig. She was put into service on March 16, 1944 and a little over a year later, in April 14, 1945 she was at the bottom of the North Sea. The boat’s emblem was a white stork on a black shield with green beak and legs. U-1206 was one of the late-war boats that had been fitted with new deepwater high-pressure toilets, allowing their use while running at depth. These toilets were a rather complicated procedure, so special technicians were trained to operate them. Operating the toilets incorrectly…in the wrong sequence could result in waste or seawater flowing back into the hull. Not only would it have been a nasty mess, it could be dangerous.

German submarine U-1206 was a Type VIIC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II. Construction started on June 12, 1943 at F. Schichau GmbH in Danzig. She was put into service on March 16, 1944 and a little over a year later, in April 14, 1945 she was at the bottom of the North Sea. The boat’s emblem was a white stork on a black shield with green beak and legs. U-1206 was one of the late-war boats that had been fitted with new deepwater high-pressure toilets, allowing their use while running at depth. These toilets were a rather complicated procedure, so special technicians were trained to operate them. Operating the toilets incorrectly…in the wrong sequence could result in waste or seawater flowing back into the hull. Not only would it have been a nasty mess, it could be dangerous.

On April 14, 1945, just 24 days before the end of World War II in Europe, U-1206 was cruising at a depth of 200 feet, eight nautical miles off Peterhead, Scotland. A sailor decided that he knew the procedure for flushing the toilet, and after performing the procedure wrong, caused large amounts of seawater to flood the boat. According to the Commander’s official report, while in the engine room helping to repair one of the diesel engines, he was informed that a malfunction involving the toilet caused a leak in the forward section. The leak flooded the submarine’s batteries, which were located directly beneath toilet, causing them to generate chlorine gas. The Commander had no alternative but to surface. Immediately upon surfacing, basically right in the middle of several British patrol boats, U-1206 was torpedoed, forcing Schlitt to scuttle the submarine. One man died in the attack, three men drowned in the heavy seas after abandoning the vessel and 46 were captured.

I can’t imagine the frustration the Commander must have felt. Prior to the stupidity of one sailor, the submarine had been cruising along in relative safety. A forced surfacing was sure to put them in harms way, but the gas in

the submarine would most certainly kill them too. He did the only thing he could do, and U-1206 was at the bottom of the North Sea less than an hour later, where it would remain, hidden During survey work for the BP Forties Field oil pipeline to Cruden Bay in the mid 1970s, the remains of U-1206 were found at 57°21’N 01°39’W in approximately 230 feet of water.

the submarine would most certainly kill them too. He did the only thing he could do, and U-1206 was at the bottom of the North Sea less than an hour later, where it would remain, hidden During survey work for the BP Forties Field oil pipeline to Cruden Bay in the mid 1970s, the remains of U-1206 were found at 57°21’N 01°39’W in approximately 230 feet of water.

Following the horrific attacks on our country on September 11, 2001, all planes were told to land at the nearest possible airport immediately. Before long, there were no planes in United States airspace, other than military planes. The feeling was an eerie one. Maybe other people considered the international flights, but for some odd reason, I did not until I read a book called, “When The World Came To Town.” When the United States closed its airspace that day, it left literally thousands of people out over the oceans with nowhere to go…almost. Those that had not passed the point of no return, most likely turned around, but there were many planes that had to go on. Nevertheless, they could not land in the United States, so our neighbors in Canada came to the rescue.

Following the horrific attacks on our country on September 11, 2001, all planes were told to land at the nearest possible airport immediately. Before long, there were no planes in United States airspace, other than military planes. The feeling was an eerie one. Maybe other people considered the international flights, but for some odd reason, I did not until I read a book called, “When The World Came To Town.” When the United States closed its airspace that day, it left literally thousands of people out over the oceans with nowhere to go…almost. Those that had not passed the point of no return, most likely turned around, but there were many planes that had to go on. Nevertheless, they could not land in the United States, so our neighbors in Canada came to the rescue.

There were only a couple of places that planes en route to the east coast of the United States could land. One of them was Gander, Newfoundland…a small town of 9,561 people in 2001…and nearby communities like Gambo, Lewisporte, Appleton and Norris Arm. When the US airports shut down, it left 38 planes and 6,500 people who were heading west over the Atlantic, with very few options. Enter Gander, Newfoundland. Gander airport received those 38 planes, and opened everything in their town to those 6,500 people and a couple of dogs. The passengers were mostly in shock…both because of what had just happened, and because all the people of Gander simply dropped everything to personally take care of the stunned passengers.

At the time, the school bus drivers were on strike. As if they were one person, they all laid down their picket signs and went to drive their unexpected guests around…not just from the airport, but anywhere they needed or wanted to go. Pharmacists filled prescriptions for free. Shop owners declined payment for goods sold to the passengers. The arena at the Gander Community Centre became a giant walk-in fridge for food donations. The people brought their best dishes…comfort food for the passengers, all of whom were feeling, like every United States citizen was feeling…nauseous, anxious, and scared. If people began to cry, someone was there to comfort them and allow them to talk it out. People opened their homes, allowing people to stay with them, and others to shower in their homes. Homes were not locked. They were opened to the people from the planes…at all hours. If people just needed to get out of the community center, someone took them wherever they wanted to go…even just for a drive.

The tarmac at Gander International Airport quickly became a parking lot. There were planes everywhere. I don’t think a plane could take off, if they wanted to, but then, nobody was really going anywhere. The United States was in a “holding pattern,” and for Gander, the same applied, to a degree. They were busy helping their unexpected guests to feel more comfortable, and less anxious, if that was possible. Nevertheless, the passengers were not bored. The townspeople entertained them with music, tours, a church service, and even a birthday party for a passenger with a birthday. The townspeople took the passengers to Walmart to get them

the clothing and other necessities they had to leave in the cargo hold of the plane. Whatever they wanted or needed, they were supplied with. The people of Gander did it all, and asked for nothing in return. All that is great, but the truly wonderful thing that the people of Gander, Gambo, Lewisporte, Appleton and Norris Arm did for the stranded passengers, was to offer friendship…a friendship that has endured through the 19 years since that fateful day.

the clothing and other necessities they had to leave in the cargo hold of the plane. Whatever they wanted or needed, they were supplied with. The people of Gander did it all, and asked for nothing in return. All that is great, but the truly wonderful thing that the people of Gander, Gambo, Lewisporte, Appleton and Norris Arm did for the stranded passengers, was to offer friendship…a friendship that has endured through the 19 years since that fateful day.

When we think about the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, most people are first saddened and appalled, and then we wonder…why?? We should also wonder…why September 11th. I’m sure that the terrorists pick a day, without really knowing why that was the day they picked, but I find the parallels concerning September 11, to be beyond coincidental. I can’t really take credit for pointing out the parallels either, that honor goes to Jonathan Cahn, who is the author of “The Harbinger II,” among other books on the same subject. When you hear about the parallels…well, it’s almost eerie. Cahn pointed out some things that I had no idea about, and it is my guess that I am not alone in not knowing about these parallels, and the good news is that you can research them for yourself to see if what I am telling you is correct or not.

When we think about the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, most people are first saddened and appalled, and then we wonder…why?? We should also wonder…why September 11th. I’m sure that the terrorists pick a day, without really knowing why that was the day they picked, but I find the parallels concerning September 11, to be beyond coincidental. I can’t really take credit for pointing out the parallels either, that honor goes to Jonathan Cahn, who is the author of “The Harbinger II,” among other books on the same subject. When you hear about the parallels…well, it’s almost eerie. Cahn pointed out some things that I had no idea about, and it is my guess that I am not alone in not knowing about these parallels, and the good news is that you can research them for yourself to see if what I am telling you is correct or not.

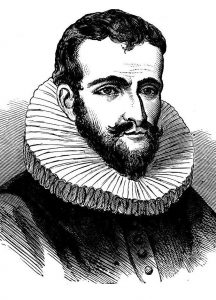

New York City was founded in 1609, when Henry Hudson sailed into what is now the Upper Bay of New York Harbor in the Dutch East India Company ship, Halve Maen (Half Moon in English). Hudson was looking for a Northwest Passage to Asia. He landed on what is now Manhattan, just a short distance from where the World Trade Center had stood in modern times…on September 11, 1609. When I heard that, I had to check it out for myself, and sure enough, on September 11, 1609, Henry Hudson sailed to the southern point of modern day Manhattan. September 11th…seriously!!

So the terrorists flew into the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 just a short distance from Henry Hudson’s famous landing, but what of the Pentagon. Well, during World War II, when it was decided that the military needed a single headquarters, the plan began to take shape. The location was chosen, and then came the groundbreaking ceremony on…you guessed it, September 11, 1941. I found it not only shocking that the attacks came on the days of the founding of Manhattan and the Pentagon, but that those two separate places

could have that date in common. Could the terrorists have known about these two obscure events in the passage of time. I don’t think so, because I don’t think they were that smart. They simply did what they were told. Could Osama Bin Laden or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed have known. I suppose so, but what would they have done if the dates hadn’t matched. None of that made any sense. From their prospective, they simply wanted to attack America. To me, the date is beyond coincidence. It is prophetic and it is spiritual. You can check out the research and draw your own conclusion, or better yet, read the book. There is much more there…in the book…far too much to say here, but it got my attention.

could have that date in common. Could the terrorists have known about these two obscure events in the passage of time. I don’t think so, because I don’t think they were that smart. They simply did what they were told. Could Osama Bin Laden or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed have known. I suppose so, but what would they have done if the dates hadn’t matched. None of that made any sense. From their prospective, they simply wanted to attack America. To me, the date is beyond coincidence. It is prophetic and it is spiritual. You can check out the research and draw your own conclusion, or better yet, read the book. There is much more there…in the book…far too much to say here, but it got my attention.

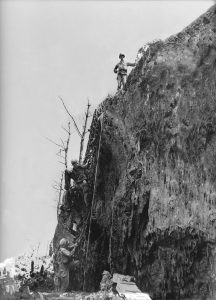

As with any war, there are a number of people who, because of their religious or personal beliefs, cannot bring themselves to participate in the taking of another life. That leaves war off the table for them. Desmond Doss, born February 7, 1919, was a United States Army corporal who served as a combat medic in the infantry during World War II. That’s what happened to the conscientious objectors. They didn’t just get to go home, they stayed in as a medic, without a gun, who was known as “Preacher” to those around him. Doss may not have had a gun, but he managed to be awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device, for exceptional valor in aiding wounded soldiers under fire in Guam and the Philippines. Doss went on to distinguish himself in the Battle of Okinawa, saved the lives of 50–100 wounded infantrymen atop the area known by the 96th Division as the Maeda Escarpment or Hacksaw Ridge. With that action, Doss became the only conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor.

As with any war, there are a number of people who, because of their religious or personal beliefs, cannot bring themselves to participate in the taking of another life. That leaves war off the table for them. Desmond Doss, born February 7, 1919, was a United States Army corporal who served as a combat medic in the infantry during World War II. That’s what happened to the conscientious objectors. They didn’t just get to go home, they stayed in as a medic, without a gun, who was known as “Preacher” to those around him. Doss may not have had a gun, but he managed to be awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device, for exceptional valor in aiding wounded soldiers under fire in Guam and the Philippines. Doss went on to distinguish himself in the Battle of Okinawa, saved the lives of 50–100 wounded infantrymen atop the area known by the 96th Division as the Maeda Escarpment or Hacksaw Ridge. With that action, Doss became the only conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor.

Before World War II began, Doss worked as a joiner in a shipyard in Newport News, Virginia. While he didn’t feel like he could kill people, Doss did want to serve his country. So, despite being  offered a deferment because he worked in the shipyards, Doss joined the Army on April 1, 1942 at Camp Lee, Virginia. Doss was sent to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for training with the reactivated 77th Infantry Division. His brother, Harold Doss, served aboard the USS Lindsey. Still, Doss refused to kill an enemy soldier or carry a weapon into combat because of his personal beliefs as a Seventh-day Adventist. He consequently became a medic assigned to the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division. While he did not carry a weapon, Doss was wounded four times in Okinawa, because he put himself in harms way to help his fellow soldiers. He was evacuated on May 21, 1945, aboard the USS Mercy. Doss suffered a left arm fracture from a sniper’s bullet and at one point had seventeen pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body.

offered a deferment because he worked in the shipyards, Doss joined the Army on April 1, 1942 at Camp Lee, Virginia. Doss was sent to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for training with the reactivated 77th Infantry Division. His brother, Harold Doss, served aboard the USS Lindsey. Still, Doss refused to kill an enemy soldier or carry a weapon into combat because of his personal beliefs as a Seventh-day Adventist. He consequently became a medic assigned to the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division. While he did not carry a weapon, Doss was wounded four times in Okinawa, because he put himself in harms way to help his fellow soldiers. He was evacuated on May 21, 1945, aboard the USS Mercy. Doss suffered a left arm fracture from a sniper’s bullet and at one point had seventeen pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body.

After the war, Doss went home to continue his career in carpentry. Unfortunately, extensive damage to his left  arm made carpentry a thing of his past. In 1946, Doss was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which he had contracted on Leyte. He underwent treatment for five and a half years, losing a lung and five ribs before being discharged from the hospital in August 1951 with 90% disability. He continued to receive treatment from the military. Then, an overdose of antibiotics rendered him completely deaf in 1976, after which he was given 100% disability. He received a cochlear implant in 1988, and was able to finally hear again. Despite the severity of his injuries, Doss managed to raise a family on a small farm in Rising Fawn, Georgia. He married Dorothy Pauline Schutte on August 17, 1942, and they had one child, Desmond “Tommy” Doss Jr, born in 1946. Dorothy died on November 17, 1991 in a car accident, in which Desmond was driving and lost control of the vehicle. It was a devastating loss. Doss remarried on July 1, 1993, to Frances May Duman. In March of 2006, he was hospitalized for difficulty breathing. Doss died on March 23, 2006, at his home in Piedmont, Alabama.

arm made carpentry a thing of his past. In 1946, Doss was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which he had contracted on Leyte. He underwent treatment for five and a half years, losing a lung and five ribs before being discharged from the hospital in August 1951 with 90% disability. He continued to receive treatment from the military. Then, an overdose of antibiotics rendered him completely deaf in 1976, after which he was given 100% disability. He received a cochlear implant in 1988, and was able to finally hear again. Despite the severity of his injuries, Doss managed to raise a family on a small farm in Rising Fawn, Georgia. He married Dorothy Pauline Schutte on August 17, 1942, and they had one child, Desmond “Tommy” Doss Jr, born in 1946. Dorothy died on November 17, 1991 in a car accident, in which Desmond was driving and lost control of the vehicle. It was a devastating loss. Doss remarried on July 1, 1993, to Frances May Duman. In March of 2006, he was hospitalized for difficulty breathing. Doss died on March 23, 2006, at his home in Piedmont, Alabama.

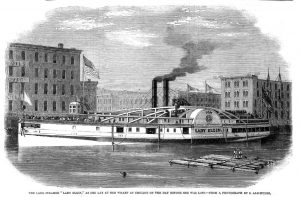

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

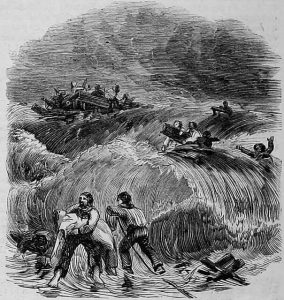

Suddenly, the lumber on the Augusta shifted, causing the two ships to collide. Instantly, the party atmosphere that had been on the Lady Elgin, turned to chaos and confusion. The Augusta received only minor damage in the collision, and kept right on sailing to Chicago. It wasn’t an unusual occurrence in those days. It’s possible that the Augusta assumed that if it wasn’t badly hurt, that larger ship probably wasn’t either. I can’t say for sure, but I know that this collision, in which the Augusta did not stop is not the first I have heard of such an incident in Maritime history. A large hole in the side of the Lady Elgin doomed the ship, which sank within thirty minutes. Only three lifeboats were able to be loaded and set into the water. The ships large upper hurricane deck fell straight into the water and served as a raft for some forty people.

The ship had crashed two to three miles off the shore of Highland Park, but the waves were so strong that survivors, bodies, and debris were all swept down to the northern shore of Winnetka. In those days, the lakeshore in this area consisted of a narrow strip of beach rising up to clay cliffs almost 50 feet high. An angry line of breakers churned up from the storm were crashing ashore. Around 6:30am the first of the three lifeboats made it to shore in the vicinity of the Jared Gage house…which still stands at 1175 Whitebridge Hill Road. A desperate call for assistance went out to the town from the Gage house. The people of Winnetka rode  horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

The crowds on the bluffs and beaches watched as pieces of wreckage washed up near the site of the present Winnetka water tower. By 10:00am, the bluffs were littered with people who had been strong enough to withstand the fierce storm of the previous night. Lastly came the hurricane deck with Captain Wilson and eight survivors whom the storm had thus far spared. Then, before their eyes, this storm-battered deck was dashed to pieces on an offshore sandbar and all on board were lost.

The storm left a tremendous undertow, creating the tragic situation…the exhausted victims had drifted close enough to the Winnetka shore to see it, only to be held back by the breakers. As the horrified onlookers watch, they died in full view of the people on shore, who could do nothing but watch. Men were lowered from the bluff with rope tied around their waists in attempts to pull people in to safety. One Evanston seminary student, Edward Spencer, is credited with saving 18 lives. Spencer is said to have repeatedly rushed into the sea, being battered by debris in order to save more people. I do not know, but I suspect that he is some relation to me on my Spencer side, and I feel honored that he was such a heroic figure. Spencer is said to have wondered many times in the aftermath, “Did I do my best?” It is the mark of a hero, never to feel like they did enough. Another man, Joseph Conrad, was said to have pulled 28 to safety. Other unknown rescuers pulled in survivors up and  down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

The Gage house, the Artemas Carter house at 515 Sheridan Road, and other Winnetka residences served as temporary hospitals. The newly-built Winnetka train depot served as a morgue. Winnetka residents brought food and clothing for the survivors. It is estimated that 302 people lost their lives that day, the exact number is unknown, as the ships manifest went down with the ship. The 1860 census shows only 130 residents in the town of Winnetka. The tragedy captured the nation’s attention, but was quickly overshadowed by the 1860 elections and the Civil War. Such is the way of things. An tragic event is only well remembered, until another comes to take its place.

When a volcano hasn’t erupted for 400 years, people naturally assume that the volcano is dead, but volcanos don’t really die, they become dormant. In the case of Mount Sinabung, located on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. On August 29, 2010, Mount Sinabung experienced a minor eruption. The mountain had been rumbling for several days. Ash spewed into the atmosphere up to 0.93 miles high and lava was seen overflowing the crater. The four centuries of quiet were over. The most recent eruption prior to 2010 was in 1600. On August 31, 6,000 of the 30,000 villagers who had been evacuated returned to their homes. As volcanoes go, a category “A” must be monitored frequently, because it is very active. Mount Sinabung was assigned to a category “B,” meaning that no one would really know that more eruptions were on the horizon, unless more rumbling was heard in the days ahead

When a volcano hasn’t erupted for 400 years, people naturally assume that the volcano is dead, but volcanos don’t really die, they become dormant. In the case of Mount Sinabung, located on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. On August 29, 2010, Mount Sinabung experienced a minor eruption. The mountain had been rumbling for several days. Ash spewed into the atmosphere up to 0.93 miles high and lava was seen overflowing the crater. The four centuries of quiet were over. The most recent eruption prior to 2010 was in 1600. On August 31, 6,000 of the 30,000 villagers who had been evacuated returned to their homes. As volcanoes go, a category “A” must be monitored frequently, because it is very active. Mount Sinabung was assigned to a category “B,” meaning that no one would really know that more eruptions were on the horizon, unless more rumbling was heard in the days ahead  of the eruption. Following the eruption, the Indonesian Red Cross Society and the Health Ministry of Indonesia sent doctors and medicines to the area. The National Disaster Management Agency also provided face masks and food to assist the evacuees.

of the eruption. Following the eruption, the Indonesian Red Cross Society and the Health Ministry of Indonesia sent doctors and medicines to the area. The National Disaster Management Agency also provided face masks and food to assist the evacuees.

On Friday, September 3, 2010, two more eruptions occurred. The first one happened at 4:45am, forcing more villagers to leave their houses…some of whom had only returned the day before. This Was the biggest eruption to that date…maybe another reason to start to feel apprehensive. In this eruption, ash spewed up into the atmosphere about 1.9 miles high. In the hours before the eruption, a warning had been issued through the volcanology agency, and most villagers were prepared to leave quickly. A second eruption occurred the same evening, around 6pm. The eruption came with earthquakes which were felt up to 15.5 miles away from the volcano.

Then, on Tuesday September 7, Mount Sinabung erupted yet again…its biggest eruption since it had become active on August 29, 2010. Finally, Mount Sinabung had reached the point of a category “A” listing. Experts warned of more eruptions to come and began monitoring it closely. Indonesia’s chief vulcanologist, Surono, said  “It was the biggest eruption yet and the sound was heard from 8 kilometers away. The smoke was 5,000 meters in the air.” Heavy rain mixed with the ash to form muddy coatings, a centimeter thick, on buildings and trees. Electricity in one village was cut off, but there were no casualties in that instance. At least 14 people were killed in the early days of the eruptions. Following the reawakening of Mount Sinabung, it has erupted numerous times over the years since, with eruptions every year. It is a highly volatile volcano. The last eruption of Mount Sinabung was on August 10, 2020, producing an eruption column of volcanic materials as high as 16,400 feet into the sky. It doesn’t look like Mount Sinabung will become dormant again anytime soon.

“It was the biggest eruption yet and the sound was heard from 8 kilometers away. The smoke was 5,000 meters in the air.” Heavy rain mixed with the ash to form muddy coatings, a centimeter thick, on buildings and trees. Electricity in one village was cut off, but there were no casualties in that instance. At least 14 people were killed in the early days of the eruptions. Following the reawakening of Mount Sinabung, it has erupted numerous times over the years since, with eruptions every year. It is a highly volatile volcano. The last eruption of Mount Sinabung was on August 10, 2020, producing an eruption column of volcanic materials as high as 16,400 feet into the sky. It doesn’t look like Mount Sinabung will become dormant again anytime soon.