History

Most people have heard of, and seen, the James Bond movies. Of course, Bond is a fictional British agent, known as 007, and his character has been played by a number of actors over the years, but in reality, he is fictional. Renato Levi, who was also known as CHEESE, MR. ROSE, LAMBERT, EMILE, or ROBERTO, was a Jewish-Italian adventurer and double-agent for the British in World War II. Levi was instrumental in setting up a wireless transmitter in Cairo. The transmitter fed false information to the Axis powers over the course of the war. It was a great tool for the Allies. Unfortunately, Levi was captured and imprisoned shortly after he accomplished his mission. Levi’s “CHEESE” network helped to outflank Rommel at the battle of El Alamein in Egypt, as well as placing other, strategic misinformation that aided the Allies, including at Normandy.

Most people have heard of, and seen, the James Bond movies. Of course, Bond is a fictional British agent, known as 007, and his character has been played by a number of actors over the years, but in reality, he is fictional. Renato Levi, who was also known as CHEESE, MR. ROSE, LAMBERT, EMILE, or ROBERTO, was a Jewish-Italian adventurer and double-agent for the British in World War II. Levi was instrumental in setting up a wireless transmitter in Cairo. The transmitter fed false information to the Axis powers over the course of the war. It was a great tool for the Allies. Unfortunately, Levi was captured and imprisoned shortly after he accomplished his mission. Levi’s “CHEESE” network helped to outflank Rommel at the battle of El Alamein in Egypt, as well as placing other, strategic misinformation that aided the Allies, including at Normandy.

Levi almost always flew under the radar, especially in the British National Archives. Even in recent books about spies and counter-intelligence, the accomplishments of Renato Levi still receive barely a mention and the specifics about his part in all this is often confused. In all reality, Levi’s files have only recently been released, and even then Levi’s, aliases “Cheese,” “Lambert,” or “Mr. Rose” seem to be identified openly only once in his classified dossier. Indeed, in his national documents, there is evidence of redaction everywhere, including Levi’s primary codename “CHEESE” has been carefully handwritten in tiny, blocky letters over white-out, in order to re-establish a place in history.

The CHEESE network, out of Cairo, took a significant hit to its credibility when Levi was arrested and convicted in late 1941 or early 1942. The British came up with an imaginary agent. “Paul Nicossof” was able to regain and retain the trust of the Germans, which is one of the most interesting features of this story. Thanks to the expert manipulations of the British Intelligence operatives controlling the wireless, the CHEESE network was considered credible again by June of 1942…just in time for “A” Force to start planting counter-intelligence prior to the commencement of Operation Bertram at El Alamein in Egypt during October of 1942.

Most interesting to note are the ways that the intelligence operatives used payment schedules…or, rather, the German’s lack of payment to “Paul Nicossof”…to establish credibility about the fictitious informant’s information. “Nicossof” was portrayed as moody and inconsistent, because efforts to pay him were always unsuccessful. His “handlers” credited Germany’s inability to pay “Nicossof” as the way they were able to extend his character beyond the “impasse” that would normally constitute a non-military informant. “Nicossof” could portray himself as the “man who brought Rommel to Egypt,” which would get him paid for his troubles at last, as well as the glory and medals that went with it…all to a fictitious agent!!

Most interesting to note are the ways that the intelligence operatives used payment schedules…or, rather, the German’s lack of payment to “Paul Nicossof”…to establish credibility about the fictitious informant’s information. “Nicossof” was portrayed as moody and inconsistent, because efforts to pay him were always unsuccessful. His “handlers” credited Germany’s inability to pay “Nicossof” as the way they were able to extend his character beyond the “impasse” that would normally constitute a non-military informant. “Nicossof” could portray himself as the “man who brought Rommel to Egypt,” which would get him paid for his troubles at last, as well as the glory and medals that went with it…all to a fictitious agent!!

Perhaps because of the British Intelligence’s efforts to make “Nicossof” convincing and because Levi was so good under duress in prison, the Germans never really lost faith in the CHEESE operative network. They were starved for information, and CHEESE held the only promise for any intelligence about the Middle East. The Germans blamed the Italians for the confinement of their only key agent in the Middle East, Renato Levi. For whatever the reason, the Germans trusted Levi, but he never broke or compromised his duty to the Allied forces.

After looking at these newly declassified documents some people have tried to press Levi into the service of a “Hero Spy” figure, but in reality, Levi was a far more complicated figure and these whitewashed narratives don’t really tell the whole story of Levi’s complexity, nor the complexity of his work. Levi’s story also reveals much about the inner workings of the German Abwehr and the nature of the Italian Intelligence operations. Levi’s British handlers speculated that it was unlikely that the German and Italian Intelligence bureaus had a great deal of communication between them. The Germans were really overly satisfied with Levi’s original purpose of  establishing a wireless transmitter network, to their detriment in the end.

establishing a wireless transmitter network, to their detriment in the end.

It seems that Levi’s ultimate fate is unknown. It is true that the CHEESE network was in full swing throughout the war, and many have credited “CHEESE” with hoodwinking the Germans in a big way on many occasions. Perhaps Levi was again affiliated with CHEESE after his release, or maybe not. Regardless, Renato Levi, who had always loved travel, intrigue, and a really good lie, did a remarkable service to the Allied forces by instituting one of the best and most productive counter-intelligence operations of World War II, and he kept it all safe.

Very few people these days haven’t heard of Captain Chesley B. “Sulley” Sullenberger III and co-pilot Jeff Skiles who made their now famous landing on the Hudson River in New York City after a bird strike left them powerless. We all know that everyone “miraculously” survived that crash landing. It was an undeniable miracle, but it was not the first time such a thing had happened. On October 16, 1956, Pan Am Flight 6, a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser on a nighttime flight from Honolulu to San Francisco, developed engine trouble in one and then two of its four engines. Pan Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. I can only imagine the thoughts racing through the minds of the pilots, given the fact that they were not going to find a highway or a field on which to land safely. There was only ocean. This was not the first time a plane had to ditch in the ocean, but I doubt that was any comfort to the men who were flying the plane, since the other ditching events had fatalities.

Very few people these days haven’t heard of Captain Chesley B. “Sulley” Sullenberger III and co-pilot Jeff Skiles who made their now famous landing on the Hudson River in New York City after a bird strike left them powerless. We all know that everyone “miraculously” survived that crash landing. It was an undeniable miracle, but it was not the first time such a thing had happened. On October 16, 1956, Pan Am Flight 6, a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser on a nighttime flight from Honolulu to San Francisco, developed engine trouble in one and then two of its four engines. Pan Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. I can only imagine the thoughts racing through the minds of the pilots, given the fact that they were not going to find a highway or a field on which to land safely. There was only ocean. This was not the first time a plane had to ditch in the ocean, but I doubt that was any comfort to the men who were flying the plane, since the other ditching events had fatalities.

Pan Am World Airways first started flying in 1927, delivering mail between Florida and Cuba. The carrier was based out of New York City for nearly 30 years, until it went out of business in 1991. The airline left a legacy of firsts. “It was first across the Atlantic, first with flights across the Pacific and the first to offer around-the-world service,” said Kelly Cusack, the curator of the Pan Am Museum Foundation. Most airlines celebrate a lot of their firsts, but there is one first that no airline wants to celebrate, or have on their list of firsts at all…a crash. Nevertheless, on October 16, 1956, a crash was exactly what was going to happen. This crash took place 53 years before “Sulley’s” famous water landing into the Hudson River. “This is a particularly memorable and a proud part of our legacy because of two words: happy ending,” said Jeff Kriendler, who was Pan Am’s vice president for corporate communications in the 1980s and has written several anthologies about the airline. Airlines have ditched in the ocean before, but this was the first to do so with no fatalities. Like “Sulley’s” famous flight, ditching in the ocean without fatalities…was unheard of. Unlike “Sulley’s” landing, which was caught on camera, a nighttime flight in the middle of the ocean in 1956 was not likely to be caught on camera.

The flight started out smoothly, but then developed engine trouble in one, and then two of its four engines. Pan  Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. The decision to land the plane in the sea with 24 passengers and seven crew members aboard was not made until all other options had been considered. Captain Richard Ogg, the pilot, wrote an account of the episode a year later, saying that he had to weigh many factors. Should he jettison fuel and try to land on the water immediately or fly until daylight provided better visibility? One thing was clear, the bad propeller was causing the plane to burn fuel too fast. He would not make it to San Francisco or Honolulu. Apparently, it was no coincidence that the ship was nearby. In the early days of long flights over water, Coast Guard ships were positioned in the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans, offering weather information to flight crews and relaying radio messages, according to Doak Walker, a Coast Guard historian who participated in the rescue of Flight 6. In preparation, the cutters were placed near what was expected to be the point of no return. That is the area where a plane would have burned too much fuel to turn back in case of an emergency.

Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. The decision to land the plane in the sea with 24 passengers and seven crew members aboard was not made until all other options had been considered. Captain Richard Ogg, the pilot, wrote an account of the episode a year later, saying that he had to weigh many factors. Should he jettison fuel and try to land on the water immediately or fly until daylight provided better visibility? One thing was clear, the bad propeller was causing the plane to burn fuel too fast. He would not make it to San Francisco or Honolulu. Apparently, it was no coincidence that the ship was nearby. In the early days of long flights over water, Coast Guard ships were positioned in the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans, offering weather information to flight crews and relaying radio messages, according to Doak Walker, a Coast Guard historian who participated in the rescue of Flight 6. In preparation, the cutters were placed near what was expected to be the point of no return. That is the area where a plane would have burned too much fuel to turn back in case of an emergency.

Ogg opted to fly an eight-mile circuit above the Pontchartrain until morning while planning for the water landing. Remembering that during another Pan Am Stratocruiser ditching, the tail had broken off, Ogg had the passengers in the back of the plane move forward and asked those seated by the engine to move as well. “We will try to stay aloft until daylight,” Ogg radioed to the Pontchartrain. When the passengers learned the flight would circle and not attempt to land in the dark, “it gave them a lot of confidence,” said Frank Garcia, 91, the flight engineer and a guest of honor at the Pan Am event. Passengers were also comforted knowing “someone was out there waiting to give them as much aid as they can,” Garcia said. Standing watch on the cutter just after 8 a.m., Walker, 83, recalled that “the seas were extremely calm and the weather was good and we were hoping there wouldn’t be much of a problem.”

Just as Ogg had expected, the tail broke off as soon as the plane hit the sea. Then the nose of the airliner went under the water. “I felt as if somebody had grabbed the seat of my pants and was pulling,” Garcia said. “I saw the water. I was more frightened if the windows broke, then the water would come in.” From the cockpit,  all Garcia saw was water. “I can’t tell you how many seconds, it was less than a minute, and I saw the water receding,” Garcia said, as the front of plane surfaced. On the Pontchartrain many thought they had just witnessed a disaster, Walker said. “It was so sad,” he said. “We knew nobody could survive that.” Rescue boats sped toward the plane, while other Coast Guardsmen filmed the event. Captured moments included life rafts bobbing by the aircraft’s fuselage, transferring survivors to rescue boats, the sinking plane, and the lifting of twin toddlers, Maureen and Elizabeth Gordon, from a lifeboat into waiting seamen’s arms. And, everyone was saved. It was a miracle at sea.

all Garcia saw was water. “I can’t tell you how many seconds, it was less than a minute, and I saw the water receding,” Garcia said, as the front of plane surfaced. On the Pontchartrain many thought they had just witnessed a disaster, Walker said. “It was so sad,” he said. “We knew nobody could survive that.” Rescue boats sped toward the plane, while other Coast Guardsmen filmed the event. Captured moments included life rafts bobbing by the aircraft’s fuselage, transferring survivors to rescue boats, the sinking plane, and the lifting of twin toddlers, Maureen and Elizabeth Gordon, from a lifeboat into waiting seamen’s arms. And, everyone was saved. It was a miracle at sea.

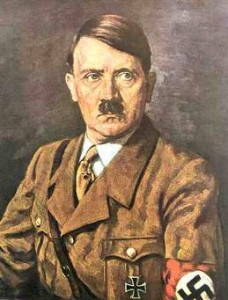

Sometimes, it’s a close call that saves the life of a person, because a difference of inches could have meant the difference between life and death. That was the case for young Corporal Adolf Hitler when he was temporarily blinded on October 14, 1918, by a gas shell that was close enough to temporarily blind him, but unfortunately for the rest of the world, not close enough to kill him. The British shell was part of an attack at Ypres Salient in Belgium, and in the aftermath, Hitler found himself evacuated to a German military hospital at Pasewalk, in Pomerania. Of course, Hitler considered this a great good fortune, with the exception of the temporary blindness. I find myself wishing that the shell had been closer, because the difference of inches could have changed the world, and especially the victims of the Holocaust.

Sometimes, it’s a close call that saves the life of a person, because a difference of inches could have meant the difference between life and death. That was the case for young Corporal Adolf Hitler when he was temporarily blinded on October 14, 1918, by a gas shell that was close enough to temporarily blind him, but unfortunately for the rest of the world, not close enough to kill him. The British shell was part of an attack at Ypres Salient in Belgium, and in the aftermath, Hitler found himself evacuated to a German military hospital at Pasewalk, in Pomerania. Of course, Hitler considered this a great good fortune, with the exception of the temporary blindness. I find myself wishing that the shell had been closer, because the difference of inches could have changed the world, and especially the victims of the Holocaust.

Like many young men of the period, Hitler was drafted for Austrian military service, but when he reported, he was turned down due to lack of fitness. In the summer of 1914, Hitler had moved to Munich. When World War I began, he asked for and received special permission to enlist as a German soldier. It all seemed like a noble thing to do. Hitler was a member of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment. He traveled to France in October 1914. There, he saw heavy action during the First Battle of Ypres, earning the Iron Cross that December for dragging a wounded comrade to safety. These things rather surprise me, give Hitler’s reputation for thinking only of himself.

Over the course of the next two years, Hitler took part in some of the fiercest struggles of the war, including  the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of the Somme. He was wounded in the leg by a shell blast on October 7, 1916, near Bapaume, France. Following his hospital stay. Hitler was sent to recover near Berlin, after which he returned to his old unit by February 1917. According to Hans Mend, a comrade of Hitler, he was given to rants on the dismal state of morale and dedication to the cause on the home front in Germany. According to Mend, “He sat in the corner of our mess holding his head between his hands in deep contemplation. Suddenly he would leap up, and running about excitedly, say that in spite of our big guns victory would be denied us, for the invisible foes of the German people were a greater danger than the biggest cannon of the enemy.” It would seem that Hitler’s crazed mind was beginning to present itself. As I look at a picture of Hitler as a young man, I wonder what happened to him that changed him so much. Yung Hitler didn’t look like the crazed, evil dictator the world knew

the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of the Somme. He was wounded in the leg by a shell blast on October 7, 1916, near Bapaume, France. Following his hospital stay. Hitler was sent to recover near Berlin, after which he returned to his old unit by February 1917. According to Hans Mend, a comrade of Hitler, he was given to rants on the dismal state of morale and dedication to the cause on the home front in Germany. According to Mend, “He sat in the corner of our mess holding his head between his hands in deep contemplation. Suddenly he would leap up, and running about excitedly, say that in spite of our big guns victory would be denied us, for the invisible foes of the German people were a greater danger than the biggest cannon of the enemy.” It would seem that Hitler’s crazed mind was beginning to present itself. As I look at a picture of Hitler as a young man, I wonder what happened to him that changed him so much. Yung Hitler didn’t look like the crazed, evil dictator the world knew

Hitler continued to earn citations for bravery over the next year, including an Iron Cross 1st Class for “personal bravery and general merit” in August 1918 for single-handedly capturing a group of French soldiers hiding in a shell hole during the final German offensive on the Western Front. Then, on October 14, 1918, Hitler received the injury that put an end to his service in World War I. He learned of the German surrender while recovering at Pasewalk. Hitler was furious and frustrated by the news. He said, “I staggered and stumbled back to my  ward and buried my aching head between the blankets and pillow.” Hitler felt he and his fellow soldiers had been betrayed by the German people. I’m amazed that he did not put them in the camps too. In 1941, Hitler as Führer would reveal the degree to which his career and its terrible legacy had been shaped by the World War I, writing that “I brought back home with me my experiences at the front; out of them I built my National Socialist community.”

ward and buried my aching head between the blankets and pillow.” Hitler felt he and his fellow soldiers had been betrayed by the German people. I’m amazed that he did not put them in the camps too. In 1941, Hitler as Führer would reveal the degree to which his career and its terrible legacy had been shaped by the World War I, writing that “I brought back home with me my experiences at the front; out of them I built my National Socialist community.”

When I think of what might have been, but for a difference of inches, I find it very ironic. If that shell had hit just a few inches closer, perhaps Hitler would have died a hero in his nation, before he could become the epitome of evil…to the world, and to many of his own people. I suppose World War I and II, as well as the other wars, would have still happened, but maybe, quite likely, the Holocaust would not have happened. Just a few inches. If only.

Unfortunately, not every life story is a perfect one. There are among us, who embrace evil, greed, and selfishness, as well as the need to promote themselves as far more important than they are, or ever should be allowed to be. Georgia Tann was purported to be the face of modern adoption practices. She supposedly changed the view of orphan children, from unworthy of better circumstances to simply victims of circumstance who could go on to greatness, if given the chance. She had the backing of many of the prominent members of Memphis society, and officials including Shelby County Juvenile Court Judge Camille Kelley. In reality, Tann operated a horrific human trafficking operation under the name of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society (not to be confused with the legally operated Tennessee Children’s Home) from 1924 to 1950. The non-profit corporation might have been legitimate when first chartered in 1897. Beulah George Tann was born in July 18, 1891, so she was too young to bring her evil into the society when it first began, and didn’t work there when the charter was renewed in 1913, but it was under her leadership that it became an illegal adoption agency.

Unfortunately, not every life story is a perfect one. There are among us, who embrace evil, greed, and selfishness, as well as the need to promote themselves as far more important than they are, or ever should be allowed to be. Georgia Tann was purported to be the face of modern adoption practices. She supposedly changed the view of orphan children, from unworthy of better circumstances to simply victims of circumstance who could go on to greatness, if given the chance. She had the backing of many of the prominent members of Memphis society, and officials including Shelby County Juvenile Court Judge Camille Kelley. In reality, Tann operated a horrific human trafficking operation under the name of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society (not to be confused with the legally operated Tennessee Children’s Home) from 1924 to 1950. The non-profit corporation might have been legitimate when first chartered in 1897. Beulah George Tann was born in July 18, 1891, so she was too young to bring her evil into the society when it first began, and didn’t work there when the charter was renewed in 1913, but it was under her leadership that it became an illegal adoption agency.

Tann preyed upon people who had lost their jobs due to the depression, as well as single mothers, telling them that she could help them by taking the children temporarily, until they could get back on their feet. When the parents tried to reclaim their children, they found out that they had been adopted. The parents tried to fight Tann in court, but the courts rules in favor of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society…but she didn’t stop there. She had her people take children off the streets, and even their own front porches. The children were listed as abused, neglected, or abandoned. Their names and birthdates were changed to make tracking difficult…records were routinely destroyed. She also had parents sign forms they did not understand when their babies were born, often while mothers were still under medication, saying that this would let the county pay for the birth. Parents were then told the babies had died. When their older children were taken away, they found out that they had also signed away the rights to their them too. There were many corrupt officials involved in this. The corruption ran deep, and everyone covered up for everyone else in the ring.

The problem the children faced after being removed from the protection of their parents, who love them; is that the people who take them do not value the heart, mind, and bodies of these children. The children kept there were routinely malnourished, beaten, imprisoned, and abused…in every sense of the word. They were not allowed to go to school, and they were taken to viewing parties so potential…rich parents could take the ones they liked. Tann took children from poor people and gave them to “high-types” of people…for a price, of course. The cost of the adoptions was high and there were additional fees is the child had to be transported to another state. Only the rich could afford them. Tann pocketed the lion’s share of the fees received, and she lived well, while the children often survived on cornmeal mush. It is estimated that over 500 children died in the group homes run by Georgia Tann. Some were buried in mass graves. The final resting place of many others is unknown.

Tann’s rich parents were victims too. They had unknowingly adopted children who shouldn’t have been up for adoption. If they found out what she had done, Tann blackmailed them into silence. Actress, Joan Crawford’s twin daughters Cathy and Cynthia were adopted through the agency. Actors, June Allyson and husband Dick Powell also used the Memphis-based home for adopting a child. Professional wrestler Ric Flair was stolen from his birth mother and placed for adoption. Auto racer Gene Tapia had a son stolen by the agency. A 1950 state investigation found that Tann had arranged for thousands of adoptions under questionable means. State investigators discovered that the Society was a front for a broad black market adoption ring, headed by Tann. They also found record irregularities and secret bank accounts. In some cases, Tann skimmed as much as 80 to 90% of the adoption fees when children were placed out of state. Officials found that Judge Camille Kelley had

railroaded through hundreds of adoptions without following state laws. Kelley received payments from Tann for her assistance. Tann died in the fall of 1950, before the case could go to trial. Kelley announced that she would retire after 20 years on the bench. Kelley was not prosecuted for her role in the scandal and died in 1955. Over the years that Tann headed up the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, she amassed at least 5,000 victims. The true number will most likely never be known, and in reality, continues to grow with each generation of children born, who will never know their true heritage.

railroaded through hundreds of adoptions without following state laws. Kelley received payments from Tann for her assistance. Tann died in the fall of 1950, before the case could go to trial. Kelley announced that she would retire after 20 years on the bench. Kelley was not prosecuted for her role in the scandal and died in 1955. Over the years that Tann headed up the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, she amassed at least 5,000 victims. The true number will most likely never be known, and in reality, continues to grow with each generation of children born, who will never know their true heritage.

When my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to Washington state a few years ago, I began to take an interest in the Pacific Northwest. I think mostly it was so that I could tell her about things to go see. I don’t know how interested a non-tourist is about those things, but I have certainly found that I am.

When my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to Washington state a few years ago, I began to take an interest in the Pacific Northwest. I think mostly it was so that I could tell her about things to go see. I don’t know how interested a non-tourist is about those things, but I have certainly found that I am.

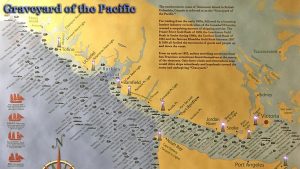

Like anyplace where there is shipping, there is likely to be shipwrecks. The Great Lakes, with their horrible weather conditions in the winter months, are littered with them. The waters of the Pacific Northwest have somehow always seemed rather benign to me, but as I learned about an area called The Graveyard of the Pacific, it occurred to me that maybe they are anything but benign. The Graveyard of the Pacific is a somewhat loosely defined stretch of the Pacific Northwest coast stretching from around Tillamook Bay on the Oregon Coast, running northward past the treacherous Columbia Bar and Juan de Fuca Strait, and up the rocky western coast of Vancouver Island to Cape Scott. Unpredictable weather conditions, fog and coastal characteristics such as shifting sandbars, tidal rips and rocky reefs and shorelines which are common to the area, have claimed more than 2,000 shipwrecks in this area. That makes the area, in my mind anyway, practically cluttered with debris.

In a way, it makes perfect sense, given the fact that many of our nation’s storms enter the continental United States from that area…excluding the tropical hurricanes, of course. With the unpredictable and frequently heavy weather and a rocky coastline, especially along Vancouver Island and its northwestern tip at Cape Scott, have endangered and wrecked thousands of marine vessels since European exploration of the area began in the 18th century. The area has claimed more than 2000 vessels and 700 lives near the Columbia Bar alone, and one book about shipwrecks lists 484 wrecks at the south and west sides of Vancouver Island. Combinations of fog, wind, storm, current and waves have crashed hundreds of ships in the region by the middle of the twentieth century, including famous wrecks in regional history.

The area is home to some famous and dangerous landmarks…Columbia Bar, a giant sandbar at the mouth of the Columbia River; Cape Flattery Reefs and rocks lining the west coast of Vancouver Island; and the Strait of San Juan de Fuca. The shipwreck charts of the area are studded with wreck sites. There have been a number of salvage attempts, but they are often unsuccessful or of limited success, and physical wreckage is usually minimal anyway due to the age of many wrecks. The weather is very unpredictable and the sea conditions harsh. This brings extensive damage to the vessels at the time they were wrecked.

The term, The Graveyard of the Pacific is believed to have originated from the earliest days of the maritime fur trade, not only as increasing numbers of traders’ ships began to be wrecked, but also because of the ongoing

state of incipient warfare in the area between Russia, Spain, Great Britain, and native tribal peoples, making it one of the most dangerous and deadly regions to trade in the Pacific for political as well as climatic reasons. Although major wrecks have declined since the 1920s, several lives are still lost annually. The Graveyard of the Pacific remains a dangerous area, but with modern science, storms aren’t as unpredictable, so watching weather reports can prevent many dangerous situations.

state of incipient warfare in the area between Russia, Spain, Great Britain, and native tribal peoples, making it one of the most dangerous and deadly regions to trade in the Pacific for political as well as climatic reasons. Although major wrecks have declined since the 1920s, several lives are still lost annually. The Graveyard of the Pacific remains a dangerous area, but with modern science, storms aren’t as unpredictable, so watching weather reports can prevent many dangerous situations.

It seems that before every accepted type of warning system, there is a period of time when the warnings are either ignored by officials or the officials worry that such a warning will cause a panic among the people. In retrospect, however, the officials always wish that they had allowed the warnings to be posted, so that lives could have been saved. I can understand how the idea of mass panic could be a bit scary for officials, and people often don’t act in a way that could produce an orderly evacuation, in which everyone evacuates as if nothing is wrong.

It seems that before every accepted type of warning system, there is a period of time when the warnings are either ignored by officials or the officials worry that such a warning will cause a panic among the people. In retrospect, however, the officials always wish that they had allowed the warnings to be posted, so that lives could have been saved. I can understand how the idea of mass panic could be a bit scary for officials, and people often don’t act in a way that could produce an orderly evacuation, in which everyone evacuates as if nothing is wrong.

David Bernays and Charles Sawyer were two American scientists who were exploring the area around Yungay, Peru. They were climbing nearby Mount Huascarán, when they saw something that alarmed them. They noticed quite a bit of loose bedrock under a glacier. The scientists also knew that the region was prone to earthquakes. The mix of those two things, possible disasters on their own, could be catastrophic if they happened together. Bernays and Sawyer tried to save the residents of Yungay, Peru from the huge avalanche that was a very real possibility.

At the warning, the government became so outraged by the warning the scientists issued, that they ordered the them to take it back or go to prison. That was a big threat, and these were American scientists in a foreign country. I’m sure that the men were justifiably terrified. As a result of the threat and the fear it brought, the two scientists fled the country. Several years later, the men were proven right, when an avalanche killed most of Yungay’s 20,000 residents. I’m sure that being proven right didn’t do much for the two scientists’ feelings of horror at the very disaster that they had so correctly predicted. This was not going to be an “I told you so” moment. It was simply a tragedy…and it could have been prevented, if anyone had listened.

The May 31, 1970 undersea earthquake off the coast of Casma and Chimbote, north of Lima, triggered one of the most cataclysmic avalanches in recorded history. The avalanche wiped out the entire highland town of Yungay and most of its 25,000 inhabitants. Around 3:23pm, local time, while most people were tuned in to the Italy-Brazil FIFA World Cup Match, an earthquake struck the Peruvian departments of Ancash and La Libertad. The quake’s epicenter was located in the Pacific Ocean, where the Nazca Plate is subducted by the South American Plate, and recorded a magnitude of 8.0 on the Richter scale, with an intensity of up to 8 on the Mercalli scale. The quake lasted 45 seconds, and crumbled adobe homes, bridges, roads and schools across 83,000 square kilometers, an area larger than Belgium and the Netherlands combined. It was registered as one of the worst earthquakes ever to be experienced in South America. Damage and casualties were reported as far  as Tumbes, Iquitos and Pisco, as well as in some parts of Ecuador and Brazil…but in Yungay, a small highland town in the picturesque Callejon de Huaylas, founded by Domingo Santo Tomás in 1540, the earthquake triggered an even greater calamity.

as Tumbes, Iquitos and Pisco, as well as in some parts of Ecuador and Brazil…but in Yungay, a small highland town in the picturesque Callejon de Huaylas, founded by Domingo Santo Tomás in 1540, the earthquake triggered an even greater calamity.

Following the quake, the glacier on the north face of Mount Huascarán broke free, causing 10 million cubic meters of rock, ice and snow to break away and tear down its slope at more than 120 miles, per hour. As it thundered down toward Yungay, and the town of Ranrahirca on the other side of the ridge, the wave of debris picked up more glacial deposits and began to spit out mud, dust, and boulders. By the time it reached the valley, just three minutes later, the 3,000 feet wide wave was estimated to have consisted of about 80 million cubic meters of ice, mud, and rocks. Within moments, what was Yungay and its 25,000 inhabitants, many of whom had rushed into the church to pray after the earthquake struck, were buried and crushed by the landslide. The smaller village of Ranrahirca was buried as well, the second time in a decade, but it is the image of lone surviving palm trees in the Yungay cemetery that is burned into Peru’s memory.

“We were on our way from Yungay to Caraz when the earthquake struck,” survivor Mateo Casaverde recalls. “When we stepped out of the car, the earthquake was almost over. Then we heard a deep, low rumble, something distinct from the noise an earthquake makes, but not too different. It came from the Huascarán. Then we saw, half-way between Yungay and the mountain, a giant cloud of dust. Part of the Huascarán was coming toward us. It was approximately 3:24pm. Where we were, the only place that offered us relative security, was the cemetery, built upon an artificial hill, like a pre-Incan tomb. We ran approximately 100 meters before we got to the cemetery. Once I reached the top, I turned to see Yungay. I could clearly see a giant wave of gray mud, about 60 meters high. Moments later, the landslide hit the cemetery, about five meters below our feet. The sky went dark because of all the dust, mostly from all of the destroyed homes. We turned to look, and Yungay, as well as its thousands of inhabitants, had completely disappeared.”

The reported death toll from what came to be known as Peru’s Great Earthquake totaled more than 74,000 people. About 25,600 were declared missing, over 143,000 were injured and more than one million left homeless. The city of Huaraz was rubble, the valley buried in mud, and coastal towns such as Casma were also shaken to the ground. In Yungay, only some 350 people survived, including the few who were able to climb to the town’s elevated step-like cemetery. Built between 1892 and 1903, the cemetery was designed by Swiss architect Arnoldo Ruska, who also died as a result of the landslide. Among the survivors were 300 children, who had been taken to the circus at the local stadium, set on higher ground and on the outskirts of the town.

Today, Yungay is a national cemetery and the Huascarán’s victims are still vividly remembered. Because the Peruvian government has forbidden excavation in the area, crosses and tombs mark the spots where homes once stood, engraved with the names of those never found. A crushed intercity bus, four of the original palm trees that once crowned the city’s main plaza and remnants of the cathedral still stand. Though life goes on and a new Yungay has since been rebuilt, a few miles away from the original city, Peru does not forget. In 2000, in memory of the victims of the deadliest seismic disaster in the history of Latin America, the government declared May 31 “Natural Disaster Education and Reflection Day.”

Today, Yungay is a national cemetery and the Huascarán’s victims are still vividly remembered. Because the Peruvian government has forbidden excavation in the area, crosses and tombs mark the spots where homes once stood, engraved with the names of those never found. A crushed intercity bus, four of the original palm trees that once crowned the city’s main plaza and remnants of the cathedral still stand. Though life goes on and a new Yungay has since been rebuilt, a few miles away from the original city, Peru does not forget. In 2000, in memory of the victims of the deadliest seismic disaster in the history of Latin America, the government declared May 31 “Natural Disaster Education and Reflection Day.”

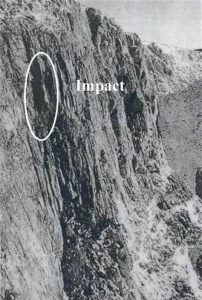

Wyoming doesn’t have as many plane crashes as other states…at least not to my knowledge. It’s probably because of the fact that with a smaller population, there are fewer flights in and out…at least in the past. That may have changed in more recent years. Nevertheless, on October 6, 1966, a DC-4…United Airlines Flight 409, with 66 people on board, flew into the side of a cliff on Medicine Bow Peak in the Snowy Mountain Range near Laramie, Wyoming. At that time, it was the worst air disaster in United States history.

Wyoming doesn’t have as many plane crashes as other states…at least not to my knowledge. It’s probably because of the fact that with a smaller population, there are fewer flights in and out…at least in the past. That may have changed in more recent years. Nevertheless, on October 6, 1966, a DC-4…United Airlines Flight 409, with 66 people on board, flew into the side of a cliff on Medicine Bow Peak in the Snowy Mountain Range near Laramie, Wyoming. At that time, it was the worst air disaster in United States history.

Lost in the disaster were three crew members, two infants, several military personnel, and five female members of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Their four-engine propeller plane took off from the now-closed Stapleton International Airport in Denver that morning. Its destination was Salt Lake City, Utah. Jet airliners didn’t exist then, and propeller-driven airplanes necessarily flew at much lower altitudes. Things like not being able to pressurize the cabin, necessitated a lower flight level. Unfortunately, it also made air travel quite a bit more hazardous. Things like terrain collisions and weather issues were more common. Weather forecasts weren’t as sophisticated and the widely dispersed technology we have today was still a dream in some scientists mind.

The normal flight path of the Denver to Salt Lake route in those days, was north of Laramie around the high points of the Snowy Mountain Range. It seems to be a long way around to us these days, but it was necessary back then. Still, pilots would occasionally fly over the range to save time. In retrospect, I’m sure many would regret that practice after hearing about United Airlines Flight 409, and the horrible outcome of that shortcut.

The night of October 5th brought high winds and snow…both normal for Wyoming this time of year. The conditions over the mountains were most likely less than ideal as UA409 crossed the range the next morning. At 7:26am on October 6th, the plane flew into the side of the mountain…at full speed. There were no “black boxes” at that, so the only way to determine the time was that the onboard clocks that were recovered after the crash were frozen at the moment of impact. According to the investigation report, the plane exploded on impact, littering the mountain with debris over a mile-long path. Two huge black marks marred the mountain, as oil from the engines splattered across the surrounding terrain. The impact site was just 25 feet below the crest of the mountain, at 12,000 feet…25 feet from clearing the top. That is so shocking…that I find it difficult to wrap my mind around that fact. If they could have made it just a little over 25 feet higher, they just might have made it.

After the impact, the tail section separated from the rest of the aircraft, fell down the cliff, and rested on a ledge halfway down. A search for the plane ensued, and an F-80 fighter jet based out of Cheyenne spotted the wreck a little more than four hours after the crash. The pilots of the jet told of bad weather in the area. With the location, rescuers headed to the area, but with the windy weather caused, it took several attempts to locate the wreckage. It took them until Thursday afternoon to actually reach the crash site. Then began the gruesome task of recovering the dead. Bodies were lowered by rope and pully down the cliff. Some bags were marked “spare parts.” All the dead were identified, and their remains carried out on horseback.

To this day, the cause of the crash is uncertain. The pilot was very skilled, and the shortcut over the mountain would not have saved a lot of time. It is unknown why he took the shortcut, or why he flew at such a low

altitude. The wreckage remains at the site to this day, as often happened back then. A hiker made a YouTube video of his trip there, where he found pieces of scrap metal, wires, and rusted engine parts from the plane. He also found a shoe that appears to be from that era. I imagine the finds left the hiker with a feeling of being in an almost hallowed ground…almost like a grave site.

altitude. The wreckage remains at the site to this day, as often happened back then. A hiker made a YouTube video of his trip there, where he found pieces of scrap metal, wires, and rusted engine parts from the plane. He also found a shoe that appears to be from that era. I imagine the finds left the hiker with a feeling of being in an almost hallowed ground…almost like a grave site.

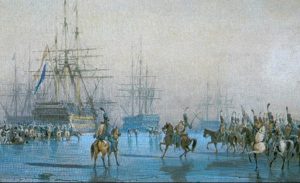

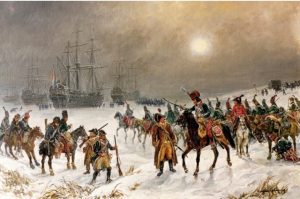

Ice flows in the world’s waterways has been known to freeze ships in place, leaving them stuck, often damaged, and sometimes…captured. The date was January 23, 1795, and the Dutch fleet was at anchor in the Zuiderzee, fifty miles north of Amsterdam. It was the height of the French Revolution, and the winter in the area was not cooperating with the fleet. In fact, some people in the port town of Den Helder said it was the worst winter they had seen in many years.

Ice flows in the world’s waterways has been known to freeze ships in place, leaving them stuck, often damaged, and sometimes…captured. The date was January 23, 1795, and the Dutch fleet was at anchor in the Zuiderzee, fifty miles north of Amsterdam. It was the height of the French Revolution, and the winter in the area was not cooperating with the fleet. In fact, some people in the port town of Den Helder said it was the worst winter they had seen in many years.

A unit of French soldiers was approaching the town that night, under the command of brigadier-general De Winter. Everyone in town knew it. A few days earlier, seven self-governing provinces had declared independence and a loose alliance. The old Republic had been ousted. Den Helder was now part of the newly declared Batavian Republic. Emotions were running high with excitement among the people, and the arrival of soldiers from the revolutionary new French Republic was welcomed. Having the Dutch Fleet in the port was oppressive, and they were ready for it to end. There was much talk of France, and of all that had been achieved there in recent years. The revolution was real, the monarchies had fled, and battles on sea and on land were being won. A bright future, free from the tyranny of the old leaders and old politics was within their grasp. The people felt hope again.

The only people who didn’t know about the French cavalry was the men on the Dutch fleet…not that it would have really mattered. It was almost midnight when the French detachment arrived. It was freezing, and the men were bundled in every garment they possessed…a great troop of horsemen riding double toward the port. People left the inns and public houses, cheering them on, and pointing out toward the Zuiderzee, where the Dutch fleet was anchored. The captain of the cavalry dismounted at the water’s edge…almost amazed. The reports were true. There, in the crisp light of the moon and stars he could see ships anchored in the bay, but he was looking not across the water. He was gazing across a great sheet of grey ice. The Zuiderzee, was shallow and fed by fresh water…and it had frozen over. The fleet in the bay was icebound and trapped. The fleet of the old Dutch Republic must have been sitting there for days, he said, but until yesterday its presence had been hidden from the town by fog and snow. Layers of snowfall had frozen and thickened the ice, which was now many feet deep.

After the scouts checked out the situation and returned, the Captain asked, “How many ships?” When he received his answer, he made his decision. This was too good a chance to miss. Messages were dispatched to General De Winter, and the soldiers were given their orders. They were to wrap the horse’s hooves in cloth, both to muffle the sound of their approach and to minimize the chance of the heavy hooves and steel horseshoes shattering the ice. They were to approach slowly and cautiously, and they were to be silent. They were to listen for the cracking of the ice, and be prepared to make an careful retreat if necessary. Onto the ice they went, horsemen and infantry, silent as the clouds of vapor that streamed from their mouths and noses as they breathed. There were eighty five warships and twenty merchant vessels trapped in the ice. The fleet represented most of the naval power of the deposed Dutch Republic, its capture would be a huge win for the French. As they advanced carefully across the ice, their ears strained for the creaking noises which would herald disaster. They became more confident. The ice held. They gathered speed. The dark ships growing larger as they came closer.

There were a few lights coming from the fleet, and the captain stopped his men short before they reached the first vessels. As quietly as possible, he sent men on foot in between the sides of the great ships. It took an hour for his men to survey the situation, and to identify the command vessel. This was a great 86 gunner, near to the French position. The captain gave his orders quickly and quietly. A detachment of horsemen was sent back, with orders to ride the shore of the Zuiderzee and establish exactly how far out the ice extended. Then, the captain dismounted and walked with the great body of his infantry round to the great command ship. They carried ropes and grappling hooks. The captain had his men prime their rifles, and then they threw hooks with ropes onto the ships.

At the sound of the first hooks on the deck a dozing watchman woke up. By the time he was awake enough to raise a cry, the captain and hundred men were on the deck. The watchman called out and ran toward the great bell, meaning to raise the alarm, but he slipped on the icy deck. There was a rush of feet, and he found himself staring up at the barrel of a musket. “Silence!” hissed the soldier. The command ship had been boarded. When the admiral was rousted from his bed and presented himself on deck, he knew that there was no hope of  resistance. The conversation he had with the young French captain of the cavalry was courteous. There would be more French troops arriving at first light, and General De Winter would arrive with them. De Winter was now the master of the Dutch fleet, and he would give clear orders. The admiral had no choice, but to give orders that the fleet surrender. When De Winter arrived in the morning the whole fleet was secured and explored in the grey morning light. The captain of the cavalry was promoted on the spot, and the admiral and his crews swore allegiance to the French Republic. A great victory had been won, without a drop of blood spilled or a single shot fired. It was the only such event ever recorded in military history.

resistance. The conversation he had with the young French captain of the cavalry was courteous. There would be more French troops arriving at first light, and General De Winter would arrive with them. De Winter was now the master of the Dutch fleet, and he would give clear orders. The admiral had no choice, but to give orders that the fleet surrender. When De Winter arrived in the morning the whole fleet was secured and explored in the grey morning light. The captain of the cavalry was promoted on the spot, and the admiral and his crews swore allegiance to the French Republic. A great victory had been won, without a drop of blood spilled or a single shot fired. It was the only such event ever recorded in military history.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

The Malkin and Kinder families went into hiding in 1942, just before the town’s Jewish ghetto was liquidated, but unfortunately, after 4 year old Fay Malkin’s father and others were killed in an old brick factory nearby. Years later in 2011, Fay Malkin told of the heroic acts of Halamajowa. Fay Malkin almost died shortly before her 5th birthday, while hiding in that hayloft. She told the Holocaust remembrance gathering at UJA-Federation of New York on May 3rd: “Hitler didn’t win, we’re here.” Malkin tells of the 20 months that the family and two other families stayed hidden in order to stay alive…and to protect their protectors, who would have also lost their lives if they were caught.

The families worried that 4-year-old Fay would give them away with her crying. The little girl promised not to cry, but that is really a lot to ask of a little girl. Malkin couldn’t control herself once in the hayloft. After trying many other approaches, the adults finally made the excruciating decision to poison little Fay in order to save the rest. Malkin would have almost certainly been killed, if they were discovered. Malkin said her memory of the incident is faint, but she remembers pushing out the pill put in her mouth. Just before she was put in a bag to be buried, a doctor who was among those hiding felt a slight pulse. She was saved. “I became the miracle child,” she said. Having lived with the story her whole life, Fay smiled when she said that her crying after that was controlled by pillows. The families were saved, not only because of the kindness and courage of their fellow townspeople, but by the miracle of a little child that didn’t die. I realize that the fact that little Fay Malkin lived through the attempted poisoning may not seem like something that saved the families, but in reality, how could they have lived with themselves? Yes, they would have been alive, but they would have been almost as bad as the Nazis who were trying to kill them.

The Malkin family lived in Sokal, then part of Poland…now in Ukraine. Before World War II, there were 6,000 Jews in Sokal. By the end of the war, only about 30 had survived, and half of them were sheltered by Halamajowa. For 20 months, the families stayed in that tiny hayloft…never daring to leave or even make a sound. Halamajowa and her daughter, Helena, risked their lives by feeding them surreptitiously and otherwise helping them, all the while disguising their actions from her neighbors and the occupying German army. In July 1944, the town was liberated by the Soviets. When the Malkin and Kindler families were finally able to come down from the hayloft, they learned that Halamajowa had also been sheltering another Jewish family in a hole dug under her kitchen floor. What these two women did was above and beyond expectation, and very brave.

Of course, most Jews never spoke of the experience. They didn’t want to get anyone in trouble, and their  protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

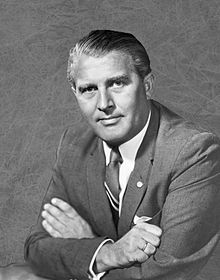

There is good that comes from science, and there is bad too, unfortunately. Things like weapons of warfare would most likely fall into the bad that comes from science. Still, weapons are necessary, and maybe it isn’t the weapon that is bad, but rather the user. Wernher von Braun was a rocket scientist in Hitler’s Germany. His job was to build bigger and more dangerous weapons. The V-2 missile was the culmination of von Braun’s work so far. On October 3, 1942, von Braun tested the V-2 missile. The missile was fired successfully from Peenemunde, as island off Germany’s Baltic coast. It traveled 118 miles in that test; and later, in evil weapon style, it proved extraordinarily deadly in the war. The V-2 missile was the precursor to the Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) of the postwar era.

There is good that comes from science, and there is bad too, unfortunately. Things like weapons of warfare would most likely fall into the bad that comes from science. Still, weapons are necessary, and maybe it isn’t the weapon that is bad, but rather the user. Wernher von Braun was a rocket scientist in Hitler’s Germany. His job was to build bigger and more dangerous weapons. The V-2 missile was the culmination of von Braun’s work so far. On October 3, 1942, von Braun tested the V-2 missile. The missile was fired successfully from Peenemunde, as island off Germany’s Baltic coast. It traveled 118 miles in that test; and later, in evil weapon style, it proved extraordinarily deadly in the war. The V-2 missile was the precursor to the Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) of the postwar era.

German scientists, led by von Braun, had been working on the development of these long-range missiles since the 1930s. I don’t know if von Braun was doing this work by choice, which would make him very likely as evil as the weapons of destruction he made, or whether, like so many of the German people under Hitler’s evil rule, he simply had no say in the matter. Whatever the case may be, von Braun was good at what he did. The science, which clearly must have fascinated him, was a work to which he was well suited. He understood it. He knew how to make it do hat he wanted it to do, and become what he wanted it to become…or, at least what he was told to make it become. Still, it took time to perfect. Three trial launches had already failed. The fourth in the series, known as A-4,  finally saw the V-2, a 12-ton rocket capable of carrying a one-ton warhead, successfully launched. I wonder just how much pressure was on von Braun at that fourth launch attempt. Could it have cost him his life, or his freedom, if he did not successfully create this weapon that Hitler wanted so badly.

finally saw the V-2, a 12-ton rocket capable of carrying a one-ton warhead, successfully launched. I wonder just how much pressure was on von Braun at that fourth launch attempt. Could it have cost him his life, or his freedom, if he did not successfully create this weapon that Hitler wanted so badly.

The V-2 was unique in several ways. First, it was virtually impossible to intercept, making it a serious threat to anyone it was aimed at. Upon launching, the missile rises six miles straight up. Then, it proceeds on an arced course, cutting off its own fuel according to the range desired. The missile then tips over and falls on its target-at a speed of almost 4,000 miles per hour. That would make it extremely difficult to blow up in flight, since hitting something moving at that speed would take serious accuracy, and heat seeking missiles were not developed yet. The missile hits with such force that it burrows itself several feet into the ground before exploding. In addition, the missile had the potential of flying a distance of 200 miles, and the launch pads were portable, making them impossible to detect before firing.

September 6, 1944 became the first real use of the V-2, when two missiles were fired at Paris. On September 8, two more were fired at England, which would be followed by more than 1,100 more during the next six months. More than 2,700 British citizens died because of the rocket attacks. After the war, both the United States and the Soviet Union captured samples of the rockets for reproduction. They also captured the scientists  responsible for their creation. Following the war, von Braun was secretly moved to the United States, along with about 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians, as part of Operation Paperclip. He worked for the United States Army on an intermediate-range ballistic missile program, and he developed the rockets that launched the United States’ first space satellite Explorer 1.

responsible for their creation. Following the war, von Braun was secretly moved to the United States, along with about 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians, as part of Operation Paperclip. He worked for the United States Army on an intermediate-range ballistic missile program, and he developed the rockets that launched the United States’ first space satellite Explorer 1.

His group was assimilated into NASA, where he served as director of the newly formed Marshall Space Flight Center and as the chief architect of the Saturn V super heavy-lift launch vehicle that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon. He also advocated for a human mission to Mars. In 1967, von Braun was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering and in 1975, he received the National Medal of Science. Von Braun died on June 16, 1977 of pancreatic cancer in Alexandria, Virginia at age 65. He was buried at the Ivy Hill Cemetery. His gravestone quotes Psalm 19:1: “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork” (KJV).