I’ve heard that in some cases, inmates who have proven themselves can become an inmate guard. I don’t know of the validity of this practice, but I do know that during the reigning Third Reich, many Jewish prisoners were forced to become guards, or Sonderkommandos, in the camps that housed the Jews. It wasn’t a paid position, or even one with added security or benefits. It was a force position…one for which the penalty of failure was death.

I’ve heard that in some cases, inmates who have proven themselves can become an inmate guard. I don’t know of the validity of this practice, but I do know that during the reigning Third Reich, many Jewish prisoners were forced to become guards, or Sonderkommandos, in the camps that housed the Jews. It wasn’t a paid position, or even one with added security or benefits. It was a force position…one for which the penalty of failure was death.

For almost three years, 2,000 Sonderkommandos did such work under threat of execution. Their fellow prisoners despised them. Everyone knew who they were, and what they did. The Sonderkommandos were both feared and hated by their fellow prisoners!! The horrors they had to endure new no bounds. Some even had to dispose of the corpses of their relatives and neighbors. I can’t imagine having to carry off a dead relative to be thrown into a mass grave without even so much as a few words said over them. The Sonderkommandos no only had to do that, but then they had to either go back to, or continue working, as if nothing had happened at all.

Being a Sonderkommando did nothing to ensure that they would survive the war, or even the next month, because the Germans either out of necessity, or just brutality, replace the Sonderkommandos every six months. I’m sure these people knew, when they were placed in the position, that their days were numbered. The problem with being a Sonderkommando was not that they fought against doing their jobs, or tried to escape, it was that they simply knew too much. These people were eyewitnesses to the atrocities of the Holocaust, and therefore a liability. They could put the Germans in prison for crimes against humanity. The Nazis could not let that happen, so they used the Sonderkommandos for six months, then killed them and replaced them with another one.

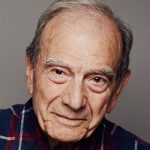

Because of this practice, only a hundred or so survived the war. These survivors were eyewitnesses to the exterminations that Holocaust deniers challenge. They were to become some of the Nazis worst nightmares. One man…Dario Gabbai, a Greek Jew, who was imprisoned at Auschwitz, is quite possibly the last of the Sonderkommandos, and certainly one of the most prominent. Gabbai settled in California after the war and  described the grim work he did in a handful of Holocaust documentaries…including “The Last Days,” which won an Academy Award for best documentary in 1999. The things Gabbai had to while he was a Sonderkommando at Auschwitz would haunt him for the rest of his life. People who have been forced to participate in horrible atrocities often blame themselves for the participation. Somehow, while logic tells us that there was nothing he could have done to stop the nightmare, he thinks he should have refused to do it, even if it meant his own death. He thinks himself a coward for being afraid to die, or for wanting desperately to live.

described the grim work he did in a handful of Holocaust documentaries…including “The Last Days,” which won an Academy Award for best documentary in 1999. The things Gabbai had to while he was a Sonderkommando at Auschwitz would haunt him for the rest of his life. People who have been forced to participate in horrible atrocities often blame themselves for the participation. Somehow, while logic tells us that there was nothing he could have done to stop the nightmare, he thinks he should have refused to do it, even if it meant his own death. He thinks himself a coward for being afraid to die, or for wanting desperately to live.

Of course, he wasn’t a coward. The very fact that he did survive makes him a hero. He was able to document the Holocaust and later relate what he witnessed. When his family reached Auschwitz, Dario’s father, mother, and younger brother were sent to the gas chambers. His sister had died as an infant, before Auschwitz. Dario and his brother, Jakob, were young…in their 20’s and strong, so they were made Sonderkommandos. He recalls seeing the doomed Jewish people taken into the gas chambers, under pretense of having a shower. Then, he remembers hearing the screams of the women and children…the crying and scratching on the walls as they desperately tried to get out…and the desperate gasping efforts to keep breathing, and then…the deathly silence. When the doors opened, the Sonderkommandos had to climb over bodies piled five and six feet high to harvest glasses, gold teeth and prosthetic limbs, before hauling out the corpses and washing down floors and walls covered in blood and excrement. Gabbai said, “I saw the people I just saw alive, the mother with the kids in their arms, some black and blue from the gas, dead. I said to myself — my mind went blind, how can I survive in this environment?” Gabbai and other Sonderkommandos had to drag the bodies to an elevator that would lift them one flight to the furnace floor. There was also a dissecting room, where jewels and other valuables hidden in body crevices would be removed. To endure such grim work, Gabbai said, he “shut down” and became an “automaton.”

The Germans preferred less common nationalities like Greek and Ladino-speaking Jews for these tasks, because they could not easily communicate the precise details of the factorylike slaughter to Polish, Hungarian and other European inmates. “They had seen too much and known too much,” Mr. Berenbaum, long-time friend of Gabbai said. It is no wonder Gabbai only wanted to get away…far away to California, after the war. When  Gabbai was liberated, he weighed 100 pounds. He couldn’t face his haunting memories. He needed to get away from all German memories. He made his way to Athens, where he helped settle refugees for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. In 1951, he immigrated to the United States through the sponsorship of the Jewish community of Cleveland, and two years later he moved to California for “its beautiful beaches, beautiful women and sunshine,” he told Mr Berenbaum. In California Gabbai finally found, if not peace, at least a light beyond the darkness of his past. In the mid-1950s, he married Dana Mitzman. They divorced, but had a daughter, Rhoda, who survives him. He passed away on March 25, 2020, at 97 years old, in California. Whether Gabbai ever achieved peace with his past or not will never be known.

Gabbai was liberated, he weighed 100 pounds. He couldn’t face his haunting memories. He needed to get away from all German memories. He made his way to Athens, where he helped settle refugees for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. In 1951, he immigrated to the United States through the sponsorship of the Jewish community of Cleveland, and two years later he moved to California for “its beautiful beaches, beautiful women and sunshine,” he told Mr Berenbaum. In California Gabbai finally found, if not peace, at least a light beyond the darkness of his past. In the mid-1950s, he married Dana Mitzman. They divorced, but had a daughter, Rhoda, who survives him. He passed away on March 25, 2020, at 97 years old, in California. Whether Gabbai ever achieved peace with his past or not will never be known.

Leave a Reply