World War II

The USS Indianapolis (CL/CA-35) was a Portland-class heavy cruiser of the United States Navy, named for the city of Indianapolis, Indiana. The ship was launched in 1931, the vessel served as the flagship for the commander of Scouting Force 1 for eight years, then as flagship for Admiral Raymond Spruance in 1943 and 1944 while he commanded the Fifth Fleet in battles across the Central Pacific during World War II. Those were tumultuous times, and sometimes things “fell through the cracks,” but what happened to the USS Indianapolis was seriously unthinkable.

The USS Indianapolis (CL/CA-35) was a Portland-class heavy cruiser of the United States Navy, named for the city of Indianapolis, Indiana. The ship was launched in 1931, the vessel served as the flagship for the commander of Scouting Force 1 for eight years, then as flagship for Admiral Raymond Spruance in 1943 and 1944 while he commanded the Fifth Fleet in battles across the Central Pacific during World War II. Those were tumultuous times, and sometimes things “fell through the cracks,” but what happened to the USS Indianapolis was seriously unthinkable.

In July 1945, after the Indianapolis completed a top-secret high-speed trip to deliver parts of Little Boy, the first nuclear weapon ever used in combat, to the United States Army Air Force Base on the island of Tinian, they subsequently departed for Guam and then it was on to the Philippines on training duty. Little Boy was the bomb that was going to effectively end the war, but the war was not over yet, and it was imperative that everyone be on high alert. The waters in many areas of the world were filled with hidden dangers…namely, German U-Boats and Imperial Japanese Navy Submarines. Many a ship was sunk by these hidden enemies.

At 12:05am on July 30, 1945, the USS Indianapolis was torpedoed by the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-58, while en route to the Philippines. The mighty ship sank in just 12 minutes. There were 1,195 crewmen aboard, and approximately 300 went down with the ship, unable to get to the deck in time. The remaining 890 men were faced with exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and shark attacks while stranded in the open ocean with few lifeboats and almost no food or water. The scene was horrible. The men in the water could not necessarily see the sharks, but the screams of their fellow crewmen were unmistakable. And if the crew wasn’t dying by shark attack, they were slowly dying at the hands of the elements. Dehydration caused many to drink the saltwater that was in abundance around them, but soon it poisoned them, and instead of saving them, it killed them.

Because of the speed with which USS Indianapolis sank, there was no time to send a distress signal or even  deploy all of the lifeboats and equipment. The men knew they would need to survive until their ship was overdue and reported missing. They didn’t know how long it would take, and this is where the Navy failed these men. Navy directive 10CL45, which meant no reporting of combatant ships that failed to arrive. No search until by accident someone saw an oil slick. When Indianapolis was overdue, the people who would have reported it as overdue, simply assumed that Indianapolis might have been redeployed to another training area, since that was part of their mission. According to the directive, no search crews were sent out. These men were unthinkably alone in the vast sea…and no help was coming. In fact, the Navy only learned of the sinking four days later, when survivors were spotted by the crew of a PV-1 Ventura on routine patrol. By the time the rescue began, only 316 of the 890 men who survived the original sinking were still alive. The sinking of Indianapolis and Navy directive 10CL45 resulted in the greatest single loss of life at sea from a single ship in the history of the US Navy.

deploy all of the lifeboats and equipment. The men knew they would need to survive until their ship was overdue and reported missing. They didn’t know how long it would take, and this is where the Navy failed these men. Navy directive 10CL45, which meant no reporting of combatant ships that failed to arrive. No search until by accident someone saw an oil slick. When Indianapolis was overdue, the people who would have reported it as overdue, simply assumed that Indianapolis might have been redeployed to another training area, since that was part of their mission. According to the directive, no search crews were sent out. These men were unthinkably alone in the vast sea…and no help was coming. In fact, the Navy only learned of the sinking four days later, when survivors were spotted by the crew of a PV-1 Ventura on routine patrol. By the time the rescue began, only 316 of the 890 men who survived the original sinking were still alive. The sinking of Indianapolis and Navy directive 10CL45 resulted in the greatest single loss of life at sea from a single ship in the history of the US Navy.

Built in Seattle, Washington by Boeing, the B-17G, which was later converted to a B-17H for use as an emergency air-sea rescue plane. It was equipped with a Higgins A-1 lifeboat attached to the lower fuselage. The plane and crew including Pilot, 1st Lieutenant William C Motsinger; Co-Pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Robert W Ball; Crew, 1st Lieutenant Rollin C Marsh; Engineer, Captain Norman E Zahrt; Navigator, Technical Sergeant Robert W Conger; Gunner, Staff Sergeant Gerard J Doody; Crew, Staff Sergeant Charles J Parkins; Crew, Sergeant Charles Edward Hurn; Crew, Sergeant Elliott Leroy Griffin; and Crew, Sergeant Otis E Anderson Jr; was assigned to the 20th Air Force, 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron. The plane was given no known name or nose art, which happened more than people knew, but it had a Radio Call Sign of “Jukebox 21.”

Built in Seattle, Washington by Boeing, the B-17G, which was later converted to a B-17H for use as an emergency air-sea rescue plane. It was equipped with a Higgins A-1 lifeboat attached to the lower fuselage. The plane and crew including Pilot, 1st Lieutenant William C Motsinger; Co-Pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Robert W Ball; Crew, 1st Lieutenant Rollin C Marsh; Engineer, Captain Norman E Zahrt; Navigator, Technical Sergeant Robert W Conger; Gunner, Staff Sergeant Gerard J Doody; Crew, Staff Sergeant Charles J Parkins; Crew, Sergeant Charles Edward Hurn; Crew, Sergeant Elliott Leroy Griffin; and Crew, Sergeant Otis E Anderson Jr; was assigned to the 20th Air Force, 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron. The plane was given no known name or nose art, which happened more than people knew, but it had a Radio Call Sign of “Jukebox 21.”

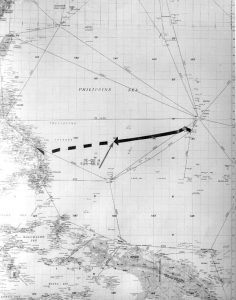

B-17H Flying Fortress Serial Number 43-38882, aka Jukebox 21, took off from Motoyama Number 1 Airfield on Iwo Jima, on July 25, 1945, on a night search mission for F4U Corsair 81319 that crashed the day before near Arai at roughly over Lat 34° 35′ N, Long 137° 35′ E on the southern coast of Honshu, Japan. The weather was good, and yet Jukebox 21 was lost, without making a distress signal. That fact made the circumstances of the crash hard to figure, and only known when the B-17 failed to return. The crew was officially listed as Missing In Action, and later as killed in action.

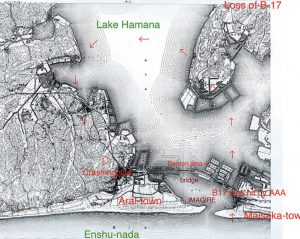

The B-17 flew over Maisaka near the Benten Jima bridge, flying northward at an altitude of roughly 984 feet. Crossing the coast, 75mm anti-aircraft guns on the south side of the highway at Benten Jima opened fire on the bomber. Jukebox 21 was hit by anti-aircraft fire, one of the engines began smoking as the plane flew northward, then attempted to circle to the west over Lake Hamana, then southward. Trailing black smoke, one of the engines on the right wing broke off before the bomber crashed at Yakute to the northwest of Arai. Jukebox 21 impacted pine trees before crashing into the ground nose first at Yakute, to the northwest of Arai. Immediately after the crash, Japanese civilians ran to the crash site and observed several mounds of debris and fire and observed the rescue boat in the wreckage. There were no survivors. Thirty minutes after the crash, Japanese Keibodan (wartime guards) reached the crash site and extinguished the fire. The bodies of the ten crew were recovered, all badly burned from the fire and no identification was possible. Afterwards, the bodies of the crew were cremated and buried at the nearby Arai crematorium, along with the body of the Corsair pilot that crashed the previous day.

Twelve Allied aircraft participated in a search over two days under the direction of Major Ivan K Mays. No wreckage was located, and all stations and ships were told to be on the lookout for this bomber. On May 22, 1947 US Army investigators visited Arai to investigate the possibilities of any atrocities in connection with the death of this crew, but found none. During their visit, they interrogated Katsumi Kumagai the former Kempei Tai commander for Arai who explained how the B-17 crashed and how the crew’s bodies were recovered, cremated, and buried. Afterwards, the remains of the crew were recovered and transported to the United States for permanent burial. Somewhat strangely, the Japanese placed a memorial to the men of Jukebox 21 at the Jingu-ji Temple in Kosai, Japan.

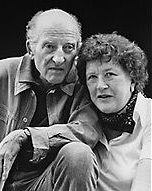

Most of us know Julia Child as a famous chef, who mainly focused on French cuisine, as well as an author of cookbooks, but that is only one aspect of her life. Born Julia Carolyn McWilliams in Pasadena, California on August 15, 1912, she was the daughter of John McWilliams Jr, and Julia Carolyn “Caro” (Weston) McWilliams. She came from wealth as privilege, her dad being a Princeton Graduate and prominent land manager, and her mom being a paper-company heiress. She was the eldest of three children, followed by John McWilliams III and Dorothy (McWilliams) Cousins. Child and her siblings were all unusually tall, and loved outdoor sports. After she graduated, Julia went on to major in history in college, after college took a job as a copywriter for a furniture company in New York City.

Most of us know Julia Child as a famous chef, who mainly focused on French cuisine, as well as an author of cookbooks, but that is only one aspect of her life. Born Julia Carolyn McWilliams in Pasadena, California on August 15, 1912, she was the daughter of John McWilliams Jr, and Julia Carolyn “Caro” (Weston) McWilliams. She came from wealth as privilege, her dad being a Princeton Graduate and prominent land manager, and her mom being a paper-company heiress. She was the eldest of three children, followed by John McWilliams III and Dorothy (McWilliams) Cousins. Child and her siblings were all unusually tall, and loved outdoor sports. After she graduated, Julia went on to major in history in college, after college took a job as a copywriter for a furniture company in New York City.

With the onset of World War II, Julia tried to enlist in military service, but was told that she was too tall to enlist in the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) or in the U.S. Navy’s WAVES…both facts that make no sense to me, and probably would not have been a factor these days. Nevertheless, Julia was declined that chance to serve.  Undeterred, she joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) as a typist at its headquarters in Washington but, because of her education and experience, soon was given a more responsible position as a top-secret researcher working directly for the head of OSS, General William J. Donovan. Thus began a career that would lead to being a spy for the Allied forces and have a life changing effect on Julia’s life.

Undeterred, she joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) as a typist at its headquarters in Washington but, because of her education and experience, soon was given a more responsible position as a top-secret researcher working directly for the head of OSS, General William J. Donovan. Thus began a career that would lead to being a spy for the Allied forces and have a life changing effect on Julia’s life.

In 1944, she was posted to Kandy, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Her responsibilities included “registering, cataloging and channeling a great volume of highly classified communications” for the OSS’s clandestine stations in Asia. Later she was transferred to Kunming, China, where she received the Emblem of Meritorious Civilian Service as head of the Registry of the OSS Secretariat. Asked to solve the problem of too many OSS underwater explosives being set off by curious sharks, “Child’s solution was to experiment with cooking various concoctions as a shark repellent,” a task she did in a bathtub…not much like her cooking in later years. The chemicals were sprinkled in the water near the explosives and repelled sharks…it was a great success and is still in use today. The experimental shark repellent “marked Child’s first foray into the  world of cooking” Child received an award that cited her many virtues, including her “drive and inherent cheerfulness.”

world of cooking” Child received an award that cited her many virtues, including her “drive and inherent cheerfulness.”

While in Kunming, she met Paul Cushing Child, also an OSS employee, and the two were married September 1, 1946, in Lumberville, Pennsylvania. They later relocated to Washington DC. Paul was a New Jersey native who had lived in Paris as an artist and poet. He was also known for his sophisticated palate, and introduced his wife to fine cuisine. Julia had always had a cook in her childhood home, so the idea of cooking was very foreign to her. Still, she was smart, and she began to excel in the art of cooking. It was her cooking that helped her to realize another of her goals…to become an author. Cooking was not a goal is a girl, but it was her later love of cooking that finally gave her the title of writer she had so desired. While Julia and Paul never had children, they lived a long and happy life until his passing in 1994. Then she went on until her own passing in 2004 at the good old age of 91.

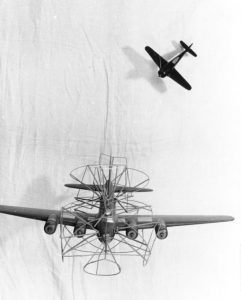

When the B-17 was built, it was designed to be a formidable weapon against the enemy, namely the Nazis and the Japanese. Early on, before long-range fighter escorts came into being, B-17s had only their .50 caliber M2, the B-17s were on their own out there. Still, the B-17 was not defenseless. With those .50 caliber M2s, the crew had the ability to fire at the enemy from every direction…almost. The job of the Messerschmitt fighters was to take down the B-17s. The Messerschmitt fighter planes were designed to break world air speed records. They were also the hope of the Germans to take down the B-17s. Still, there were all those guns to deal with. Luftwaffe fighter pilots agreed that attacking a B-17 combat box formation to encountering a fliegendes Stachelschwein, “flying porcupine,” with dozens of machine guns in a combat box aimed at them from almost every direction. The biggest downfall of the B-17 bombing formation was that they had to fly straight, making them vulnerable to German flak. It was the first line of defense the Germans had when the bombers came in.

When the B-17 was built, it was designed to be a formidable weapon against the enemy, namely the Nazis and the Japanese. Early on, before long-range fighter escorts came into being, B-17s had only their .50 caliber M2, the B-17s were on their own out there. Still, the B-17 was not defenseless. With those .50 caliber M2s, the crew had the ability to fire at the enemy from every direction…almost. The job of the Messerschmitt fighters was to take down the B-17s. The Messerschmitt fighter planes were designed to break world air speed records. They were also the hope of the Germans to take down the B-17s. Still, there were all those guns to deal with. Luftwaffe fighter pilots agreed that attacking a B-17 combat box formation to encountering a fliegendes Stachelschwein, “flying porcupine,” with dozens of machine guns in a combat box aimed at them from almost every direction. The biggest downfall of the B-17 bombing formation was that they had to fly straight, making them vulnerable to German flak. It was the first line of defense the Germans had when the bombers came in.

In a 1943 survey, the USAAF found that over half the bombers shot down by the Germans had left the protection of the main formation. The Germans needed a training plan. The United States developed the bomb-group formation, which evolved into the staggered combat box formation in which all the B-17s could safely cover any others in their formation with their machine guns, making a formation of bombers a dangerous target to engage by enemy fighters. The Messerschmitt fighters were fast, but they could not just fly at the formation. They would be shot down for sure. So, they looked for the bomber that had been hit and had to pull out of formation. Then they would move in for the kill. Moreover, German fighter aircraft later developed the tactic of high-speed strafing passes rather than engaging with individual aircraft to inflict damage with minimum risk. It was a way of not fully engaging the “flying porcupine.” As a result, the B-17s’ loss rate was up to 25% on some early missions. They needed something more to provide a kind of shield against the enemy.

It was not until the advent of long-range fighter escorts (particularly the North American P-51 Mustang) and the resulting degradation of the Luftwaffe as an effective interceptor force between February and June 1944, that the B-17 became strategically potent. They needed the P-15 Mustang to keep the Messerschmitts off of them. So in the end, the German training didn’t do them much good against the “flying porcupine.”

Sometimes an evil leader can come in and before anyone realizes it, the danger that came in with him is real. Unfortunately, not every elected leader is a good one, and when an elected leader, begins to do things like taking away the guns of the people and undermining the police, you find out just how bad they really are. Hitler was that kind of elected leader, and worse. By May of 1934, Hitler had been the chancellor of Germany for 16 months, and the dictator for 14 months. Less than a month after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, he calls on elements of the Nazi party to act as auxiliary police. The SS (Schutzstaffel), initially Hitler’s bodyguards, and the SA (Sturmabteilung, the German Assault Division), who were the street fighters or Storm Troopers of the Nazi party, now operated as the private army of the Nazi party. SS chief Heinrich Himmler also turned the regular (nonparty) police forces into an instrument of terror. He helped forge the powerful Secret State Police (Geheime Staatspolizei), or Gestapo. These non-uniformed police used ruthless and cruel methods throughout Germany to identify and arrest political opponents and others who refused to obey laws and policies of the Nazi regime. It had taken less than a year to change everything for the people of Germany, who no longer had a say in their own lives.

Sometimes an evil leader can come in and before anyone realizes it, the danger that came in with him is real. Unfortunately, not every elected leader is a good one, and when an elected leader, begins to do things like taking away the guns of the people and undermining the police, you find out just how bad they really are. Hitler was that kind of elected leader, and worse. By May of 1934, Hitler had been the chancellor of Germany for 16 months, and the dictator for 14 months. Less than a month after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, he calls on elements of the Nazi party to act as auxiliary police. The SS (Schutzstaffel), initially Hitler’s bodyguards, and the SA (Sturmabteilung, the German Assault Division), who were the street fighters or Storm Troopers of the Nazi party, now operated as the private army of the Nazi party. SS chief Heinrich Himmler also turned the regular (nonparty) police forces into an instrument of terror. He helped forge the powerful Secret State Police (Geheime Staatspolizei), or Gestapo. These non-uniformed police used ruthless and cruel methods throughout Germany to identify and arrest political opponents and others who refused to obey laws and policies of the Nazi regime. It had taken less than a year to change everything for the people of Germany, who no longer had a say in their own lives.

While he had control, it was still not enough for the insane chancellor. Hitler, as we all know, would go on to annihilate millions of the Jewish people, as well as anyone else he considered an “undesirable” person. While I’m sure the leaders of the German government considered themselves safe, they would find out just how wrong they were on the Night of the Long Knives…also known as a Blood Purge, or putsch in German. By definition, a blood purge is “the elimination en masse by massacre or execution of individuals considered to constitute an untrustworthy or undesirable element within a party or movement. the elimination en masse by massacre or execution of individuals considered to constitute an untrustworthy or undesirable element within a party.” Hitler had decided that some of his own leaders, his trusted associates, could not be trusted. Maybe he was right, but he didn’t really have proof of his doubts. Nevertheless, He decided that there needed to be a blood purge and the Night of the Long Knives was born.

On June 30, 1934, it began, and continued on until July 2, 1934. During the purge of the Night of the Long Knives (Nacht der langen Messer) Hitler and the Nazi regime used the Schutzstaffel (SS) to deal with the perceived problem of Ernst Röhm and his Sturmabteilung (SA) brownshirts (the original Nazi paramilitary organization). The first thing Hitler did was to take out…or defund the police. Believe it or not, that took out the  last protection of the people. He also took out past opponents of the party, thinking that they might organize against them. It is estimated that at least 85 people were murdered, but many historians think that the death toll was likely in the hundreds. Most of those killed were members of the SA, other victims included close associates of Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen, several Reichswehr (German Army) generals…one of whom, Kurt von Schleicher, was formerly the Chancellor of Germany. Hitler also took out their associates. Gregor Strasser, Hitler’s former competitor for control of the Nazi Party was the next to go. At least one person was killed in a case of mistaken identity, sadly, and several innocent victims were simply killed because they “knew too much.” The Night of the Long Knives…was Hitler’s insane revenge on anyone who dared to oppose him, or even to appear to oppose him.

last protection of the people. He also took out past opponents of the party, thinking that they might organize against them. It is estimated that at least 85 people were murdered, but many historians think that the death toll was likely in the hundreds. Most of those killed were members of the SA, other victims included close associates of Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen, several Reichswehr (German Army) generals…one of whom, Kurt von Schleicher, was formerly the Chancellor of Germany. Hitler also took out their associates. Gregor Strasser, Hitler’s former competitor for control of the Nazi Party was the next to go. At least one person was killed in a case of mistaken identity, sadly, and several innocent victims were simply killed because they “knew too much.” The Night of the Long Knives…was Hitler’s insane revenge on anyone who dared to oppose him, or even to appear to oppose him.

While listening to an audible book about World War II, called “Flak,” I heard one of the men being interviewed by the author for the book say, “History is told by the survivors.” It occurred to me that in most cases, at least in eras gone by, that was the truth. In order to know what really happened, there had to be a survivor. Even today, in an era of DNA, forensic science, black boxes, and phone video, there are events that cannot be definitively explained, and causes that remain a mystery.

While listening to an audible book about World War II, called “Flak,” I heard one of the men being interviewed by the author for the book say, “History is told by the survivors.” It occurred to me that in most cases, at least in eras gone by, that was the truth. In order to know what really happened, there had to be a survivor. Even today, in an era of DNA, forensic science, black boxes, and phone video, there are events that cannot be definitively explained, and causes that remain a mystery.

In World War II, survival was one of the main necessities to properly make an account of events. One might be able to look at pictures an know that the attack was bad, but in order to understand what it meant to fly through flak, someone had to really explain what the flak looked like up close, and tell us how hot it was when it got close enough to put a hole in the fuselage of the plane. We can imagine the fear the soldiers of World War II felt, but only because someone has “painted” a picture of just how bad it was to be pinned down in a foxhole with bombs raining down all around you, and bullets flying past if you tried to get out and run. No amount of  modern technology can explain how a soldier might have felt upon looking at his helmet to find a hole in it where shrapnel pierced it, and the soldier received only a small scratch. All of the “facts” that can be gleaned from the modern technology we have simply can’t tell us about how people felt.

modern technology can explain how a soldier might have felt upon looking at his helmet to find a hole in it where shrapnel pierced it, and the soldier received only a small scratch. All of the “facts” that can be gleaned from the modern technology we have simply can’t tell us about how people felt.

My dad, Allen Spencer was a top turret gunner in a B-17G bomber stationed in Great Ashfield. He told once about the ball turret gunner being shot up, and the desperate and futile effort to save his life. It was something Dad would never forget. The bombers that crashed taking all hands down with them, left no witnesses to tell if it was shot down or had engine trouble. If the plane could be found today, they might be able to guess at the cause of the crash, but it still might not be definitive. As to the soldiers who went missing in action, it was not uncommon for their body never to be found, and so no one could document their death, unless a buddy survived. All of the war stories we have today from World War II were told by the men, and women too, who survived. We know from the ones who witnessed the planes being shot down, blown up, or crashing with engine trouble. On the battlefield, the only witnesses were the other  soldiers in the area, because the civilians had run far from the area.

soldiers in the area, because the civilians had run far from the area.

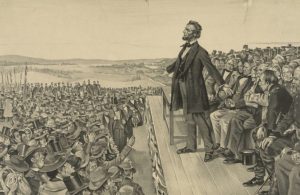

Even the non-war events of history had to have a “survivor” to tell about the event. It may not have been a violent event, but the Gettysburg Address would never have been known to anyone, if it had been spoken aloud in President Lincoln’s study with no one present. The speech might have been found later, but the depth of it’s meaning might have been completely lost had one witness not been so deeply moved by the speech. I wonder how much history was lost because no one was there to see and then survive to tell about it. It’s something to think about.

How could such a small island, sitting in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, have such a large impact during World War II? Malta is only 95 square miles, the largest of the three islands that make up the Maltese archipelago, and it had a population of 433,082 in 2019, so imagine how small the population was during World War II. Nevertheless, the British Crown Colony of Malta was a strategic location and made a pivotal contribution to the air war in the Mediterranean during World War II. I don’t suppose they wanted to be in such a position, and considering the loss of civilian lives, 1,300 in all, they paid a dear price for the war effort.

How could such a small island, sitting in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, have such a large impact during World War II? Malta is only 95 square miles, the largest of the three islands that make up the Maltese archipelago, and it had a population of 433,082 in 2019, so imagine how small the population was during World War II. Nevertheless, the British Crown Colony of Malta was a strategic location and made a pivotal contribution to the air war in the Mediterranean during World War II. I don’t suppose they wanted to be in such a position, and considering the loss of civilian lives, 1,300 in all, they paid a dear price for the war effort.

With the opening of a new front in North Africa in June 1940, came an increase to Malta’s already considerable value. There were British air and sea forces based on the island, who were able to attack the Axis ships transporting vital supplies and reinforcements from Europe. Winston Churchill called the island an “unsinkable

aircraft carrier.” Of course, Malta was a lot bigger, but it was in the sea, and it did have an air base, so it was like a large aircraft carrier. Churchill’s analogy makes sense in that planes could be dispatched from there and return to there as needed during fighting. General Erwin Rommel, the field command of Axis forces in North Africa, recognized its importance quickly. In May 1941, he warned that “Without Malta the Axis will end by losing control of North Africa.”

aircraft carrier.” Of course, Malta was a lot bigger, but it was in the sea, and it did have an air base, so it was like a large aircraft carrier. Churchill’s analogy makes sense in that planes could be dispatched from there and return to there as needed during fighting. General Erwin Rommel, the field command of Axis forces in North Africa, recognized its importance quickly. In May 1941, he warned that “Without Malta the Axis will end by losing control of North Africa.”

Being a strategic centerpiece did not, guarantee Malta’s safety. In fact, the opposite was the case. Both sides needed Malta, but only the Allies had it, so the Axis nations decided to destroy it. Between 1940 and 1942, Malta faced relentless aerial attacks by the Luftwaffe and Italian Air Force. The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force both fought to defend the island and keep it supplied. Malta was essential to the Allied war effort to disrupt Axis

supply lines to Libya, and also for supplying British armies in Egypt. The German and Italian high commands also realized the danger of a British stronghold so close to Italy. Malta was a danger to the Axis nations, and they were bent on wiping it off the face of the earth. Malta had a target on it, and they began to feel like the shooting range.

supply lines to Libya, and also for supplying British armies in Egypt. The German and Italian high commands also realized the danger of a British stronghold so close to Italy. Malta was a danger to the Axis nations, and they were bent on wiping it off the face of the earth. Malta had a target on it, and they began to feel like the shooting range.

Through the course of the war, Malta was bombed so many times that in the end, that in April 1942, the people of Malta were collectively awarded the George Cross by King George VI, which is the highest award for civilian courage and heroism. It is the only time that an entire nation received such an honor. The award was considered such an honor that the nations flag proudly displays the George Cross.

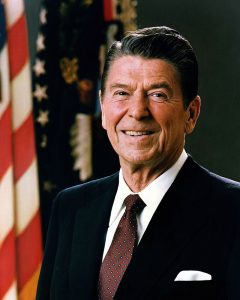

Many people would agree that one of the greatest presidents the United States ever had was Ronald Reagan. He was not what we would consider a career politician, and in fact, most would knw him as an actor long before he was a politician. Nevertheless, after spending time as the President of the Screen Actors’ Guild, where he fought against Communist influence on the screen, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California in 1966. He then became president in 1980, and the rest, as they say is history, but it is not the end.

Many people would agree that one of the greatest presidents the United States ever had was Ronald Reagan. He was not what we would consider a career politician, and in fact, most would knw him as an actor long before he was a politician. Nevertheless, after spending time as the President of the Screen Actors’ Guild, where he fought against Communist influence on the screen, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California in 1966. He then became president in 1980, and the rest, as they say is history, but it is not the end.

Ronald Reagan would prove to be a very strong person in many areas of his life…some we know of, and some, maybe not…or at least, I didn’t. After college, where Reagan was an average student, and basically considered a “jack of all trades,” he did some work in radio and such until deciding to enlist in the Army Enlisted Reserve. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Officers’ Reserve Corps of the Cavalry on May 25, 1937. On April 18, 1942, Reagan was ordered to active duty, but because of poor eyesight, he was classified for limited service only, which excluded him from serving overseas. His first assignment was at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation at Fort Mason, California, as a liaison officer of the Port and Transportation Office. Upon the approval of the Army Air Forces (AAF), he applied for a transfer from the cavalry to the AAF on May 15, 1942, and was assigned to AAF Public Relations and subsequently to the First Motion Picture Unit (officially, the 18th AAF Base Unit) in Culver City, California. On January 14, 1943, he was promoted to first lieutenant and was sent to the Provisional Task Force Show Unit of “This Is The Army” at Burbank, California. He returned to the First Motion Picture Unit after completing this duty and was promoted to captain on July 22, 1943. While he did not serve in combat, President Reagan was shot. Most of us know that President Reagan survived an assassination attempt on March 30, 1981, when he and his press secretary James Brady were both shot. Also hit by gunfire from would-be assassin John Hinckley Jr outside the Washington Hilton Hotel, were Washington police officer Thomas Delahanty and Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy. President Reagan was “close to death” when he arrived at George Washington University Hospital. He was stabilized in the emergency room, then underwent emergency exploratory surgery. He recovered from his gunshot wound, and was released from the hospital on April 11, becoming the first serving US president to survive being shot in an assassination attempt. President Reagan became very popular after the attempt of his life, with the polls indicating his approval rating to be around 73 percent.

For his part, Reagan believed that God had spared his life so that he “might go on to fulfill a higher purpose.” That is true in my opinion, but it was not the first time Ronald Reagan’s life had been placed at risk. President Reagan attended Dixon High School, where he developed interests in acting, sports, and storytelling, but his first job involved working as a lifeguard at the Rock River in Lowell Park in 1927. He was a life guard there for six years, and during that time, Reagan performed 77 rescues. While much of the rest of his career was highly  public, and well known by most people, this little tidbit was rather hidden in the archives of his life. I suppose many people thought that his job as a lifeguard was a minor role within the many roles he played in his lifetime, but I doubt if the 77 people whose lives he saved as a lifeguard would consider it to be such a minor role. If you have ever been saved from drowning…and I have…you know that you will never forget that person who saved you. I never knew my rescuer’s name, but to this day, I can see her face. I was a girl of about 10 or 12 maybe, and had no training in swimming, but I had achieved the great height of 5 feet, and thought that meant I could swim in the 5 foot area of the pool, not considering that 5 feet was at the top of my head. Thank God for the girl swimming by, who pushed me to the side of the pool. Needless to say, I taught myself to swim after that, and before summer’s end I had passed my swimming test at the pool. What President Reagan did for those 77 people, was as heroic as any soldier. A flailing victim in danger of drowning can take down their would be rescuer, and then both would likely drown. It takes a special person to put their life at risk to save another, and as in many other areas of his life, President Reagan was a true hero.

public, and well known by most people, this little tidbit was rather hidden in the archives of his life. I suppose many people thought that his job as a lifeguard was a minor role within the many roles he played in his lifetime, but I doubt if the 77 people whose lives he saved as a lifeguard would consider it to be such a minor role. If you have ever been saved from drowning…and I have…you know that you will never forget that person who saved you. I never knew my rescuer’s name, but to this day, I can see her face. I was a girl of about 10 or 12 maybe, and had no training in swimming, but I had achieved the great height of 5 feet, and thought that meant I could swim in the 5 foot area of the pool, not considering that 5 feet was at the top of my head. Thank God for the girl swimming by, who pushed me to the side of the pool. Needless to say, I taught myself to swim after that, and before summer’s end I had passed my swimming test at the pool. What President Reagan did for those 77 people, was as heroic as any soldier. A flailing victim in danger of drowning can take down their would be rescuer, and then both would likely drown. It takes a special person to put their life at risk to save another, and as in many other areas of his life, President Reagan was a true hero.

We don’t often think of generals feeling anguish over men lost in the battles they are sent to fight. It’s not that we don’t realize that they feel bad for sending these men into battle, to their possible deaths, even to their probable deaths, because we do. Still, they are the generals, and far above the rank and file…the little guys. Generals, Admirals, the President…could they even realize the consequences of their decisions in the lives of the people under them? I think most of us somehow think that the generals and even the president have no idea how many people they are condemning to death by the orders they give. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

We don’t often think of generals feeling anguish over men lost in the battles they are sent to fight. It’s not that we don’t realize that they feel bad for sending these men into battle, to their possible deaths, even to their probable deaths, because we do. Still, they are the generals, and far above the rank and file…the little guys. Generals, Admirals, the President…could they even realize the consequences of their decisions in the lives of the people under them? I think most of us somehow think that the generals and even the president have no idea how many people they are condemning to death by the orders they give. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

General Eisenhower, known as “Ike” was the one with the final say in the D-Day attack that could potentially take the lives of more than 160,000 men, as well as the possible destruction of nearly 12,000 aircraft, almost 7,000 sea vessels. The attack was supposed to take place on June 5, 1944, but the weather was not cooperative. For the attack to work, several factors had to be optimally in favor of the Allies. Nevertheless, these were factors that could not be controlled by humans. Things like the tides, the moon, and the weather. They needed low tide and bright lunar conditions, limiting the possibilities to just a few days each month. The dates for June 1944 were the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh. It was a very small window, and then the weather on the fifth didn’t cooperate either. If the attack was not launched on one  of those dates, Ike would be forced to wait until June 19 to try again. Not only did that mean more deaths because of the German occupation, but keeping the attack secret was harder, the longer they had to wait.

of those dates, Ike would be forced to wait until June 19 to try again. Not only did that mean more deaths because of the German occupation, but keeping the attack secret was harder, the longer they had to wait.

Finally, it looked like June 6, 1944 was going to cooperate. All of his advisors told him that their part was a go. Finally it was time for the final decision…one that belonged only to Eisenhower. He labored over the decision. It was not one where he could decide from his lofty position and never think about it again. He knew that he was sending men to their deaths…to certain death. He couldn’t pass the buck. He couldn’t call a dozen people to see how they felt about it. He had to decide. And so he did. History has argued what his exact words were, some said, “Ok, let ‘er rip.” or “Well, we’ll go” or “All right, we move” or “OK, boys, We will go.” or “We will attack tomorrow.” I don’t suppose it really matters what he said exactly, but rather, it mattered what happened after. We now know that the Allied casualties on June 6 have been estimated at 10,000 killed, wounded, and missing in action. Among those were 6,603 Americans, 2,700 British, and 946 Canadians. It ended with an Allied victory, but it was not without cost…the loss of lives was great. Eisenhower could not “celebrate” the anniversary of D-Day, thinking that it would be like patting himself on the back, but I think that the biggest  picture of the weight that the attack placed on Eisenhower was when he was going to a reunion with the 82nd Airborne Division. Upon seeing him, the men stood, cheering and whistling. Reporter Val Lauder had spoken to him, and later watched the news broadcast of the reunion, when her mother noticed something odd. Says Lauder, “My mother, watching with me, said, ‘He’s crying. Why is he crying?’ I said, ‘He’s looking out at a roomful of men he once thought he could be sending to their death.'” That says it all. Ike didn’t just pull the plug and send those men to their deaths…never giving it another thought. The decision haunted him for years, and quite likely the rest of his life.

picture of the weight that the attack placed on Eisenhower was when he was going to a reunion with the 82nd Airborne Division. Upon seeing him, the men stood, cheering and whistling. Reporter Val Lauder had spoken to him, and later watched the news broadcast of the reunion, when her mother noticed something odd. Says Lauder, “My mother, watching with me, said, ‘He’s crying. Why is he crying?’ I said, ‘He’s looking out at a roomful of men he once thought he could be sending to their death.'” That says it all. Ike didn’t just pull the plug and send those men to their deaths…never giving it another thought. The decision haunted him for years, and quite likely the rest of his life.

Wearing a white armband with the red cross signifying that a soldier is a medic, did not guarantee their safety in combat. Bombs raining down from the sky could not distinguish the target as a medic when they fell, nor could bullets shot from the guns of the enemy. Nevertheless, they ran into the line of fire at the cry of, “Medic!!” Of course, they were scared. They knew that, at that moment, their life expectancy was about one minute. They had to dodge the bullets and bombs just to do their job. Most of us can’t imagine the fear they must have felt. Still, in that moment, they were the only thing standing between the wounded soldiers and certain death. Soldiers were stunned to see a medic running through the machine gun fire just to put a tourniquet on the battered arm of the wounded soldier. The medic risked his own life to save the lives of others.

Wearing a white armband with the red cross signifying that a soldier is a medic, did not guarantee their safety in combat. Bombs raining down from the sky could not distinguish the target as a medic when they fell, nor could bullets shot from the guns of the enemy. Nevertheless, they ran into the line of fire at the cry of, “Medic!!” Of course, they were scared. They knew that, at that moment, their life expectancy was about one minute. They had to dodge the bullets and bombs just to do their job. Most of us can’t imagine the fear they must have felt. Still, in that moment, they were the only thing standing between the wounded soldiers and certain death. Soldiers were stunned to see a medic running through the machine gun fire just to put a tourniquet on the battered arm of the wounded soldier. The medic risked his own life to save the lives of others.

The medics received the same combat training as the other infantrymen, but they didn’t carry a weapon. Imagine finding yourself in the middle of a war zone and all you have with you is a first aid kit. The idea, I’m sure, is that the soldiers will protect the medics, but can they really. The soldiers are fighting for their own lives. It’s not that they don’t want to protect the medics or their fellow soldiers, but rather that they can’t. They are too busy fighting off the enemy.

Often the men who went in as medics were volunteer conscientious objectors. I don’t know if they realized that a conscientious objector didn’t get out of the war, but rather just didn’t get a gun…for shooting or for protection. Something like that would make me reconsider conscientious objection. I’m not one that wants to kill people, but self defense is another thing entirely. When medics went through their training, the other soldiers were rather negative toward them, often calling them “pill pushers,” but all their disdain disappeared when they saw the medics in action on the battlefield. The medics were right there beside the soldiers in the  foxholes. They were with them as they advanced during offensives. Then, while the fighting raged, they went between lines attending to the wounded. They disregarded the danger to themselves, and did their duty. The tools of their trade were limited. Often their examination would be followed with a tourniquet and a morphine injection, before cleaning the wound and sprinkling sulfa powder on it. Then they bandaged the wound and dragged the wounded soldier off the field…all in a matter of minutes or less.

foxholes. They were with them as they advanced during offensives. Then, while the fighting raged, they went between lines attending to the wounded. They disregarded the danger to themselves, and did their duty. The tools of their trade were limited. Often their examination would be followed with a tourniquet and a morphine injection, before cleaning the wound and sprinkling sulfa powder on it. Then they bandaged the wound and dragged the wounded soldier off the field…all in a matter of minutes or less.

Medics were protected by the Geneva Convention, but the Red Cross that was displayed on their helmet, was a practice that was abandoned during the Vietnam War. Believe it or not, the cross on the helmet became a target for the enemy. By then, medics also had weapons…just for protection, but my guess is that they were probably glad they had it, but not so in World War II. Armed or not, many were severely injured or killed while attending to the wounded, and that made them a unique kind of hero.