World War I

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

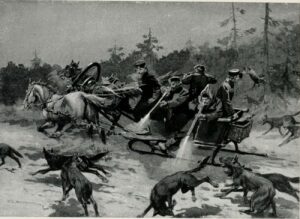

The intense fighting throughout the heavily forested region and had an unexpected side effect. Any time humans move into an area, the animal  population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

The wolves had progressed from raiding villages to taking corpses to accosting groups of soldiers outright, so  the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.

the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.

As nations prepare for war, they must also prepare the weapons of warfare. These days, and really since airplanes became reliable enough to be used in war, manufacturers have been building better and better airplanes for war. The Wright brothers, Wilber and Orville made the first airplane, which they successfully flew in 1903. Planes were first used in war in 1911, but it was in World War I, 1914-1918, that their use became commonplace. Since then, we have seen an avalanche of progress is the types and capabilities of planes.

As nations prepare for war, they must also prepare the weapons of warfare. These days, and really since airplanes became reliable enough to be used in war, manufacturers have been building better and better airplanes for war. The Wright brothers, Wilber and Orville made the first airplane, which they successfully flew in 1903. Planes were first used in war in 1911, but it was in World War I, 1914-1918, that their use became commonplace. Since then, we have seen an avalanche of progress is the types and capabilities of planes.

For me, there is no greater warplane than the B-17, but I suppose I am a bit biased because my dad served on a B-17 during World War II. That mkes me very partial to the B-17. It really was a Flying Fortress, and it was that fortress that brought my dad back home. In my book, that makes it the greatest plane ever.

During World War II, the United States had the B-17, otherwise known as the Flying Fortress…among other planes, of course. There was a plane used by Britain, that would have been the similar, to a degree to the abilities to the B-17. The Lancaster was a heavy bomber “workhorse” of a plane. When compared to the B-17, it could carry a heavier payload and fly further than the B-17. The B-17 had higher flight ceiling and better defensive firepower. Speed was about even. Those things are important, but when it came to survivability, the B-17 was the better plane in that it was far easier to bail out of than the Lancaster, meaning that the crew of a plane that was going down would really hope it  was a B-17. Only 15% of shot down crewmen survived from the Lancaster, while it was around 50% for B-17s. The Lancaster bomber had only one emergency exit…at the front of the aircraft, as opposed to four (counting the bomb bays) for the B-17.

was a B-17. Only 15% of shot down crewmen survived from the Lancaster, while it was around 50% for B-17s. The Lancaster bomber had only one emergency exit…at the front of the aircraft, as opposed to four (counting the bomb bays) for the B-17.

Both of these planes were amazing weapons of war. They were just developed, designed, and built by different companies, and different countries. They served somewhat different purposes, but they were both designed to end the murderous Axis of Evil nations, of which Hitler’s Third Reich and Japan’s evil empire were a huge part. These planes were different, but both were on the side of good and not evil. I think that I am just glad they were on the same side of the war.

The world was embarking on the industrial revolution, and it was during World War I that we found out just how much of a difference that industrial revolution could make in wartime. From the introduction of airplanes to the use of tanks and railway guns on the battlefield, soldiers had to contend not only with each other but with the productions of the factory floor. Even the recent invention of the telephone made its way into battlefield units, where soldiers used it to convey orders or direct artillery fire.

The world was embarking on the industrial revolution, and it was during World War I that we found out just how much of a difference that industrial revolution could make in wartime. From the introduction of airplanes to the use of tanks and railway guns on the battlefield, soldiers had to contend not only with each other but with the productions of the factory floor. Even the recent invention of the telephone made its way into battlefield units, where soldiers used it to convey orders or direct artillery fire.

Nevertheless, there was one area where technology was not as “up to date” as it needed to be. The telephone while a great invention, was not as reliable as the commanders of Europe would have liked. I guess that anyone who has used a modern-day cellular phone can relate that. I’m sure that they could envision the need to arrange their operations, and they weren’t too sure the information was completely safe. So, they brainstormed alternatives in an attempt to improve combat communications. The leaders of World War I turned to a much older form of communication…the carrier pigeon.

Pigeons had been used for communication for many, many years. These unsung heroes of World War I, the carrier pigeons, used by both the Allied and Central Powers, helped assist their respective commanders with an accuracy and clarity unmatched by the modern technology. The National Archives holds a vast collection of messages that these feathered fighters delivered for American soldiers. Using these messages and the history of the carrier pigeon in battle, we can look at what hardship these fearless fowls endured and how their actions  saved American lives. One of the most impressive things about the war records of the carrier pigeons was how widely the birds were used. Their service as battlefield messengers is their most known use, and the pigeons found homes in every branch of service.

saved American lives. One of the most impressive things about the war records of the carrier pigeons was how widely the birds were used. Their service as battlefield messengers is their most known use, and the pigeons found homes in every branch of service.

The rudimentary airplanes of the embattled countries used pigeons to provide updates midair. Launched mid-mission, the birds would fly back to their coops and update ground commanders on what the pilots had observed. These strange update methods were born of the essential need for leaders to know what the battlefield looked like and what the enemy was doing in its own trenches. Planes flying over and pigeons bringing the information back quickly was the best way to stay ahead of the enemy. In addition, tanks carried the birds in order to relay the advance of individual units. Even after the introduction of the radio, pigeons were often the easiest way to help coordinate tank units without exposing the men to dangerous fire. Radios to be overheard. Of course, while it made the soldiers safer, the pigeons were not necessarily safer. Many of them didn’t make it back home, having been shot down and/or used for food for starving families. Still, without a radio set, the soldiers would have had to leave the relative safety of their tanks to relay or receive orders. These birds saved lives, even if it meant sacrificing their own. Their owners also saved lives by allowing their pigeons to be involved. They were a great asset to the war effort of more than one war.

The birds’ most effective use was on the front line, as they were brought forward with their armies to help update commanders and planners in the rear. When the birds were away from their home lofts, they stayed in mobile units, which were usually converted horse carriages or even double-decker buses. I’m sure it made a

strange sight. The mobile lofts were useful when the armies outpaced their established lines of communications or when the enemy disrupted communications lines for the telegraphs or telephones, as they often did during battle. While the other Allied powers were first to use birds, the United States did not lag far behind when we entered the fray. During the course of the war, many birds performed heroic deeds in the course of service and became heroes in their own rights.

strange sight. The mobile lofts were useful when the armies outpaced their established lines of communications or when the enemy disrupted communications lines for the telegraphs or telephones, as they often did during battle. While the other Allied powers were first to use birds, the United States did not lag far behind when we entered the fray. During the course of the war, many birds performed heroic deeds in the course of service and became heroes in their own rights.

Any army is going to try attack the enemy in a sneaky way, so that their enemy is not ready…and indeed, has no idea the enemy is even nearby. When it comes to sneak attacks, we often think about the Japanese and Pearl Harbor, but they were not the only ones to do it. The Germans were just as likely to sneak up on their targets as the Japanese.

Any army is going to try attack the enemy in a sneaky way, so that their enemy is not ready…and indeed, has no idea the enemy is even nearby. When it comes to sneak attacks, we often think about the Japanese and Pearl Harbor, but they were not the only ones to do it. The Germans were just as likely to sneak up on their targets as the Japanese.

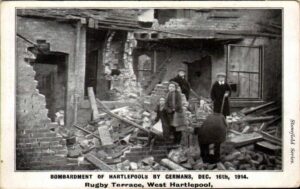

At approximately 8am on December 16, 1914, Franz von Hipper sent German battle cruisers from his Scouting Squadron to attack the British navy. The attack caught the British completely by surprise, as the Germans began heavy bombardment of Hartlepool and Scarborough…two English port cities on the North  Sea. In the attack that lasted an hour and a half, the Germans killed more than 130 civilians and wounded another 500. The attack brought a swift and vicious response from the British press, who called the incident another example of German brutality. The German navy countered that the two port cities were valid targets due to their fortified status. It didn’t justify the attack, but it was the excuse the Germans used.

Sea. In the attack that lasted an hour and a half, the Germans killed more than 130 civilians and wounded another 500. The attack brought a swift and vicious response from the British press, who called the incident another example of German brutality. The German navy countered that the two port cities were valid targets due to their fortified status. It didn’t justify the attack, but it was the excuse the Germans used.

The attack was quickly answered by the British. Two defense batteries in Hartlepool were dispatched to attack the German vessels, damaging three of them, including the heavy cruiser, Blucher. Hipper’s plan was to draw the British forces to pursue them across waters freshly laced with mines. They also had another German fleet, commanded by Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, waiting offshore to provide support. The plan fell through when the hoped-for major confrontation did not take place. Instead, the British decided to keep most of their fleet, which had been depleted by the dispatch of their major cruisers to pursue the dangerous squadron of Admiral Maximilian von Spee, in the harbor.

The Scouting Squadron attempted a repeat attack one month later using the same tactics used to surprise the British at Scarborough and Hartlepool. That attempt resulted in the Battle of Dogger Bank, where Hipper’s squadron was defeated, but unfortunately managed to avoid capture. The biggest drawback of a sneak attack is that it can really only be used once. After that the enemy is prepared and watching.

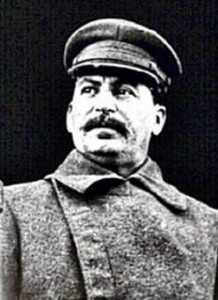

Mikhail Tukhachevsky saw it coming, really. Sometimes it’s rather sad to be right about certain things. Tukhachevsky had been nicknamed the “Red Napoleon,” meaning that he was a popular Soviet military leader in Stalin’s Red Army. Tukhachevsky had no idea just how much more important the ideology would be to Stalin, than loyalty, ability, or anything else.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky saw it coming, really. Sometimes it’s rather sad to be right about certain things. Tukhachevsky had been nicknamed the “Red Napoleon,” meaning that he was a popular Soviet military leader in Stalin’s Red Army. Tukhachevsky had no idea just how much more important the ideology would be to Stalin, than loyalty, ability, or anything else.

After his service in World War I of 1914-1917 and in the Russian Civil War of 1917-1923, from 1920 to 1921 Tukhachevsky commanded the Soviet Western Front in the Polish–Soviet War. He was moving up the ranks, and with the Soviet forces under his command, he successfully repelled the Polish forces from Western Ukraine, driving them back into Poland. Nevertheless, the Red Army suffered defeat outside of Warsaw, and the war ended in a Soviet defeat.

Tukhachevsky went on to serve as chief of staff of the Red Army from 1925 through 1928, as assistant in the People’s Commissariat of Defense after 1934, and as commander of the Volga Military District in 1937. He achieved the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union in 1935. Still, all of that did not protect him, in fact it put him in more danger, because he was just a little way under Stalin, and that was not going to bode well for him.

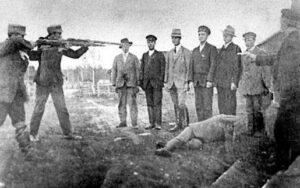

Tukhachevsky was arrested in 1936, suspected of being a German spy. The charges included Tukhachevsky’s supposed plot to overthrow Stalin. After he was arrested, the guards coerced a confession out of him. This was at the very beginning of The Great Terror, a term which historians have borrowed from the French Revolution. It refers to the paroxysm of state-organized bloodshed that overwhelmed the Communist Party and Soviet society during the years 1936-1938. It was also known as the Great Purges.

During this time, Stalin actually had over a million of his own soldiers killed for imagined wrongs. Stalin was, in  reality, half crazy. He was known to pluck a live chicken, just to see the reaction from his men. It wasn’t a really big stretch to move to killing soldiers or civilians, so the Great Terror wasn’t too far out there for him. As for Tukhachevsky, Stalin sentenced him to death in March 1938. He was executed on June 12, 1937. Even the men who had to judge the soldiers in those “sham” trials, were not free from danger. One of them, Ivan Belov said, “Tomorrow, I shall be put in the same place.” Belov was right. He was arrested on January 7, 1938. He was later executed as well. I can’t imagine how insane Stalin must have been. When you think about it, most of the men and women who were under Stalin’s rule, were too terrified to be disloyal.

reality, half crazy. He was known to pluck a live chicken, just to see the reaction from his men. It wasn’t a really big stretch to move to killing soldiers or civilians, so the Great Terror wasn’t too far out there for him. As for Tukhachevsky, Stalin sentenced him to death in March 1938. He was executed on June 12, 1937. Even the men who had to judge the soldiers in those “sham” trials, were not free from danger. One of them, Ivan Belov said, “Tomorrow, I shall be put in the same place.” Belov was right. He was arrested on January 7, 1938. He was later executed as well. I can’t imagine how insane Stalin must have been. When you think about it, most of the men and women who were under Stalin’s rule, were too terrified to be disloyal.

When a ship sinks, we expect to be able to find it, or at least find out where it went down. With radios, making it possible to receive a “May Day” call, we expect to be able to pinpoint the location of the floundering ship. Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes, no matter how hard we search for the ship, plane, and even car, but the search seems to be in vain. I think it is more common to have a search without success when it comes to a ship or even a plane in the ocean. It is so hard to see something that is so far below the surface. Still, it seems like after a century or more, there should be some breakthrough…shouldn’t there.

When a ship sinks, we expect to be able to find it, or at least find out where it went down. With radios, making it possible to receive a “May Day” call, we expect to be able to pinpoint the location of the floundering ship. Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes, no matter how hard we search for the ship, plane, and even car, but the search seems to be in vain. I think it is more common to have a search without success when it comes to a ship or even a plane in the ocean. It is so hard to see something that is so far below the surface. Still, it seems like after a century or more, there should be some breakthrough…shouldn’t there.

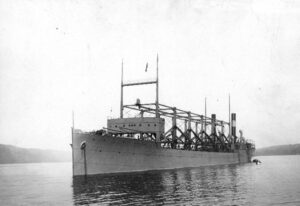

A 550-foot-long naval ship, USS Cyclops debuted in 1910. The ship was a bit of a jack-of-all-trades, so to speak…at least in it’s early days. It moved coal around the seas, as well as providing aid to refugees. Then, during World War I, USS Cyclops became a naval transporter. In 1918, the Cyclops, with it’s crew of 306 people and 11,000 tons of manganese, sailed from Brazil. The ship made a stop in Barbados and then sailed on toward Baltimore. Somewhere along the way, it disappeared. Strangely, there was no SOS made. It was as if the ocean had swallowed the ship up. Now one knew exactly where to look for it, because it had sailed quite a ways from its last known location. Maybe if there had been a distress call of any kind, they could have had a general location. Without that, they didn’t know if it had gone off course, or how fast it was traveling, so there was no way to be sure. It was thought that the Cyclops may have gone down in  the Puerto Rico Trench. The waters there run very deep, which would have made it very difficult to located the ship in 1918. Still, there was another hazardous area…the Bermuda Triangle, and some people thought that might be to blame.

the Puerto Rico Trench. The waters there run very deep, which would have made it very difficult to located the ship in 1918. Still, there was another hazardous area…the Bermuda Triangle, and some people thought that might be to blame.

The US Navy calls the tragedy of Cyclops, “The disappearance of this ship has been one of the most baffling mysteries in the annals of the Navy. All attempts to locate her have proved unsuccessful.” To this day, the original Cyclops has never been found. Many other ships that were lost at sea have been found, many that were lost before Cyclops, but there has been no sign of Cyclops. The mystery of Cyclops might never be solved, and considering the lives lost, that is very sad indeed.

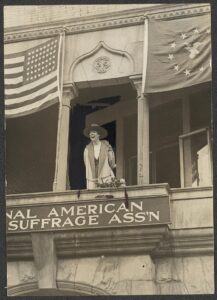

The 19th Amendment states that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In theory, this language guaranteed that all women in the United States could not be prevented from voting because of their gender. Of course, these days, no one really gives that a second thought, because…well, of course, women can vote. Who dared to think otherwise? Nevertheless, women were not always given the right to vote. In fact, for many years, men thought that politics was something that women could not possible begin to understand, and that it was a subject that was simply too harsh for the fragile female mind. Hahahaha!! We can laugh at such a thought now, because it is completely absurd, but that is what everyone thought back then…before the 19th Amendment was passed, following a fierce battle between the women suffragists and the men who ruled the nation.

The 19th Amendment states that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In theory, this language guaranteed that all women in the United States could not be prevented from voting because of their gender. Of course, these days, no one really gives that a second thought, because…well, of course, women can vote. Who dared to think otherwise? Nevertheless, women were not always given the right to vote. In fact, for many years, men thought that politics was something that women could not possible begin to understand, and that it was a subject that was simply too harsh for the fragile female mind. Hahahaha!! We can laugh at such a thought now, because it is completely absurd, but that is what everyone thought back then…before the 19th Amendment was passed, following a fierce battle between the women suffragists and the men who ruled the nation.

Nevertheless, in the midst of that fierce battle for the right to vote, an odd event took place in the form of the election of a US Congress member, Jeanette Rankin somehow being elected to Congress!! She was elected to  the US House of Representatives as a Republican from Montana in 1916, and again in 1940. Rankin was a woman, so how could this have possibly happened. She couldn’t even vote, and yet she won the election. That’s crazy. If her “fragile” mind could not be expected to understand how to vote for the office, how would she ever be able to function in the office. I mean, after all, she would be dealing with the same politics that her fellow members of congress had deemed her too fragile to understand. In fact, Jeanette Rankin would not be able to vote in an election until August 18, 1820. Her term in office ran from March 4, 1917 to March 3, 1919…during which time she was the only woman in the United States who could vote. Rankin would serve again from January 3, 1941 to January 3, 1943. Oddly, each of Rankin’s Congressional terms coincided with initiation of US military intervention in the two World Wars. A lifelong pacifist, she was one of 50 House members who opposed the declaration of war on Germany in 1917. In 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

the US House of Representatives as a Republican from Montana in 1916, and again in 1940. Rankin was a woman, so how could this have possibly happened. She couldn’t even vote, and yet she won the election. That’s crazy. If her “fragile” mind could not be expected to understand how to vote for the office, how would she ever be able to function in the office. I mean, after all, she would be dealing with the same politics that her fellow members of congress had deemed her too fragile to understand. In fact, Jeanette Rankin would not be able to vote in an election until August 18, 1820. Her term in office ran from March 4, 1917 to March 3, 1919…during which time she was the only woman in the United States who could vote. Rankin would serve again from January 3, 1941 to January 3, 1943. Oddly, each of Rankin’s Congressional terms coincided with initiation of US military intervention in the two World Wars. A lifelong pacifist, she was one of 50 House members who opposed the declaration of war on Germany in 1917. In 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Jeanette Rankin was born on June 11, 1880, near Missoula in Montana Territory. Montana would not become a  state for another nine years. Her parents were, schoolteacher Olive (née Pickering) and Scottish-Canadian immigrant John Rankin, a wealthy mill owner. She was the eldest of seven children, including five sisters (one of whom died in childhood), and a brother, Wellington, who became Montana’s attorney general, and later a Montana Supreme Court justice. One of her sisters, Edna Rankin McKinnon, became the first Montana-born woman to pass the bar exam in Montana and was an early social activist for access to birth control. With all that, it’s little wonder that she became a congresswoman. Apparently, politics ran in the family, and was likely an often-debated subject in the family home.

state for another nine years. Her parents were, schoolteacher Olive (née Pickering) and Scottish-Canadian immigrant John Rankin, a wealthy mill owner. She was the eldest of seven children, including five sisters (one of whom died in childhood), and a brother, Wellington, who became Montana’s attorney general, and later a Montana Supreme Court justice. One of her sisters, Edna Rankin McKinnon, became the first Montana-born woman to pass the bar exam in Montana and was an early social activist for access to birth control. With all that, it’s little wonder that she became a congresswoman. Apparently, politics ran in the family, and was likely an often-debated subject in the family home.

While Rankin was in her first term in office, it would seem to me that she must have felt a very strong sense of responsibility, because she was at that time the voice of all women…at least as it applied to government and politics. I can’t say that I would have agreed with all of her votes in office, especially where it applied to the two world wars, which I feel the United States needed to be involved in. Perhaps it is that aspect of being in office that the men didn’t think women were very well equipped to handle…war being such an emotional issue and all. I still think that there are many women who might struggle with the idea of sending our men into war, but then there are men who feel the same way, so I guess it is just a matter of where people stand concerning war. To date, Rankin remains the only woman ever elected to Congress from Montana.

Most of us have heard of shrapnel. Shrapnel shells have been obsolete since the end of World War I for anti-personnel use, but they were “anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell’s trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almost entirely on the shell’s velocity for their lethality.” These days, high-explosive shells are used for that role. The functioning and principles behind Shrapnel shells are fundamentally different from high-explosive shell fragmentation. Shrapnel is named for its inventor, Lieutenant-General Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842). Shrapnel was a British artillery officer, whose experiments, initially conducted on his own time and at his own expense, culminated in the design and development of a new type of artillery shell.

Most of us have heard of shrapnel. Shrapnel shells have been obsolete since the end of World War I for anti-personnel use, but they were “anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell’s trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almost entirely on the shell’s velocity for their lethality.” These days, high-explosive shells are used for that role. The functioning and principles behind Shrapnel shells are fundamentally different from high-explosive shell fragmentation. Shrapnel is named for its inventor, Lieutenant-General Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842). Shrapnel was a British artillery officer, whose experiments, initially conducted on his own time and at his own expense, culminated in the design and development of a new type of artillery shell.

Henry Shrapnel was born June 3, 1761 at Midway Manor in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, England, the ninth child of Zachariah Shrapnel and his wife, Lydia. Shrapnel became an artillery officer and inventor of a form of artillery case shot (shrapnel). He was commissioned in the  Royal Artillery in 1779, and served in Newfoundland, Gibraltar, and the West Indies. He was wounded in Flanders in the Duke of York’s unsuccessful campaign against the French in 1793. In 1804 he became an inspector of artillery and spent several years at Woolwich arsenal.

Royal Artillery in 1779, and served in Newfoundland, Gibraltar, and the West Indies. He was wounded in Flanders in the Duke of York’s unsuccessful campaign against the French in 1793. In 1804 he became an inspector of artillery and spent several years at Woolwich arsenal.

In 1784, while a lieutenant in the Royal Artillery, he perfected, with his own resources, an invention of what he called “spherical case” ammunition: a hollow cannonball filled with lead shot that burst in mid-air. He successfully demonstrated this in 1787 at Gibraltar. He intended the device as an anti-personnel weapon. In 1803, the British Army adopted a similar, but elongated explosive shell which immediately acquired the inventor’s name. It has lent the term “shrapnel” to fragmentation from artillery shells and fragmentation in general ever since, long after it was replaced by high explosive rounds, but this usage is not the original  meaning of the word. Until the end of World War I, the shells were still manufactured according to his original principles.

meaning of the word. Until the end of World War I, the shells were still manufactured according to his original principles.

In 1814, the British Government recognized Shrapnel’s contribution by awarding him £1200 (UK£ 85,000 in 2021) a year for life, however, bureaucracy kept him from receiving the full benefit of this award. He was promoted to the office of Colonel-Commandant, Royal Artillery, on March 6, 1827, and to the rank of lieutenant-general on January 10, 1837. Shrapnel lived at Peartree House, near Peartree Green, Southampton from about 1835 until his death on March 13, 1842 at Southampton, Hampshire.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

London’s Daily Telegraph explains that the fake city wasn’t just “a bunch of cardboard cutouts.” No, far from it, in fact. There were “electric lights, replica buildings, and even a copy of the Gare du Nord—the station from which high-speed trains now travel to and from London.” The painters went so far as to use paint to create “the impression of dirty glass roofs of factories.” Fake trains and railroad tracks were lit up as well. There was a phony Champs-Elysées. Many of us today would say, “How could that work? The Germans must have known where they were dropping their bombs!” Nevertheless, it stands to reason that in the early 20th century, the plan could have worked. “Radar was in its infancy in 1918, and the long-range Gotha heavy bombers being used by the German Imperial Air Force were similarly primitive,” the Telegraph notes. “Their crew would hold bombs by the fins and then drop them on any target they could see during quick sorties over major cities like Paris and London.”

No one really knows how well the plan might have worked, because it was never put to the test. World War I ended before the fake city was finished. Both the real Paris and the fake one escaped significant damage. The fake version has long since been dismantled, though photos of it still remain. I suppose it was a ghost town of  it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

To further validate the idea, French fighter pilots reported that during night flights they looked for familiar features of the landscape below when attempting to locate Paris. According to their research, railways, lakes, rivers, roads and woodland were the most useful indicators that they were in the neighborhood. Using this information, the mastermind behind the replica project, Fernand Jacopozzi, along with his team of highly capable engineers worked to make life even harder for the German pilots who were already struggling to find their bearings in an era before radar or precision targeting. Intending to confuse an enemy pilot sufficiently that he would start to doubt his own bearings, the construction of Paris’ mirror image began in earnest at Villepinte to the northeast where a working model of the Gare de l’Est gradually began to take form.

The “fake Paris” was exquisite. No detail was overlooked: “complex, sprawling networks of lights arranged skillfully creating the impression of railway tracks and avenues, as well as storm lamps clustered together on ingenious moving platforms designed to simulate vast steam trains in motion. Immense empty sheds masquerading as factories had translucent sheets of painted canvas stretched tightly across their wooden frames which were illuminated from underneath, an arrangement that to anyone passing overhead would look remarkably like the dirty glass roofs characteristic of industrial buildings. Working furnaces were also installed to add an extra dimension of reality and the factory’s lights were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, fooling enemy pilots into believing that the facsimile buildings were, in fact, occupied.”

Because World War I ended, it was only this small part of Zone A that was built. The German bombing campaign came to an end in September 1918 and the armistice was signed at Compiègne two months later. The mock factories and railway network at Villepinte were dismantled shortly after the hostilities ceased. By the beginning of the 1920s little remained of the project. Though his fascinating idea never really got much further than the drawing board, the designs of Fernand Jacopozzi inspired similarly ambitious plans in the United States during World War II.

While riding the 1880 Train on the last day of our annual trip to the Black Hills, Bob and I were sitting back, relaxing and enjoying the ride. It is a favorite part of our trip each year. One of the things that I like to do on these train rides, is to listen to what the people around us think of the journey. When you ride the train every year. You know the area, and while it is still very interesting to me, I do know the area. Others don’t, so it’s interesting to see what they think of this area I love so much. I almost feel like a local listening to the tourists who are viewing this place for the first time.

While riding the 1880 Train on the last day of our annual trip to the Black Hills, Bob and I were sitting back, relaxing and enjoying the ride. It is a favorite part of our trip each year. One of the things that I like to do on these train rides, is to listen to what the people around us think of the journey. When you ride the train every year. You know the area, and while it is still very interesting to me, I do know the area. Others don’t, so it’s interesting to see what they think of this area I love so much. I almost feel like a local listening to the tourists who are viewing this place for the first time.

This trip’s most profound conversation was a little different, and it really made me think. The train has a recorded narrative, and a little boy, about 5 or 6 years old was listening to it. So often, children don’t really listen to such things, but this little boy was rather intently listening to the message. So as he listened, the narrator said that

the train was in use during World War I and World War II, and the boy said, “What’s a war?” That really made me wonder…how nice it would be, not to know what war is. Yes, there have been wars in his lifetime, and indeed, we are in one even now, but this little boy is too young to really fathom the meaning of the word…war. He still possessed an innocence when it comes to war, killing, and death. That innocence is about to end, I suppose, because once his aunt or mother answered his question, he will forever know what a war is. He cannot go back to that innocence again. It is gone.

the train was in use during World War I and World War II, and the boy said, “What’s a war?” That really made me wonder…how nice it would be, not to know what war is. Yes, there have been wars in his lifetime, and indeed, we are in one even now, but this little boy is too young to really fathom the meaning of the word…war. He still possessed an innocence when it comes to war, killing, and death. That innocence is about to end, I suppose, because once his aunt or mother answered his question, he will forever know what a war is. He cannot go back to that innocence again. It is gone.

I came away from that experience a little sad. Children have such an innocent joy, and for this boy, that is changing. True…he won’t fully lose that innocence in one explanation, and it will depend on how much the

adults with him can soften the truth for him, but no matter what we do or say, war and death go together, and death by war is not pretty. This boy has an imagination, and if he continues to question the adults in his life, he will begin to get a clear picture of war, and what it really is. Then, as he grows, that picture will become more and more vivid. He will know what death by war means. War is a part of life, and eventually we all know what war means, but for me, the question felt sad, because I was witnessing the beginning of the end of his innocence. It’s a moment I wont easily forget either.

adults with him can soften the truth for him, but no matter what we do or say, war and death go together, and death by war is not pretty. This boy has an imagination, and if he continues to question the adults in his life, he will begin to get a clear picture of war, and what it really is. Then, as he grows, that picture will become more and more vivid. He will know what death by war means. War is a part of life, and eventually we all know what war means, but for me, the question felt sad, because I was witnessing the beginning of the end of his innocence. It’s a moment I wont easily forget either.