World War I

How could a food become a problem in a war? I mean its something you eat, not fight with. Nevertheless, during World War I, the Germans were so hated and the Third Reich was so evil, that no one among the Allies wanted anything to do with them. They didn’t even want to be associated with anything that even remotely sounded like it was German. With that in mind, the word “hamburger” came to mind. It was decided that the “hamburger” was just a little too German to be allowed to continue being served with that name. You might think that people would get mad about that, but the people were very loyal to our nation and to the cause. They couldn’t tolerate the horrific crimes against humanity they saw in front of themselves. The Germans made it very clear to the world that they were, at least will Hitler was in charge, the most horrific nation on Earth.

How could a food become a problem in a war? I mean its something you eat, not fight with. Nevertheless, during World War I, the Germans were so hated and the Third Reich was so evil, that no one among the Allies wanted anything to do with them. They didn’t even want to be associated with anything that even remotely sounded like it was German. With that in mind, the word “hamburger” came to mind. It was decided that the “hamburger” was just a little too German to be allowed to continue being served with that name. You might think that people would get mad about that, but the people were very loyal to our nation and to the cause. They couldn’t tolerate the horrific crimes against humanity they saw in front of themselves. The Germans made it very clear to the world that they were, at least will Hitler was in charge, the most horrific nation on Earth.

Because of the conflict between Germany and the rest of the world, menus were changed to purge the names of German foods from restaurant menus. The name sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage,” and hamburgers became “liberty steaks.” Frankfurters, a very German name, was also deemed unacceptable during World War I, and in some places the name was switched to “liberty sausages,” but that was one new name that didn’t quite stick…especially when someone tried the term “hot dog.” It seems almost laughable now, because why should food play such a big part in the feelings of people, but then again, in this day and age, we are facing a situation that is much the same…the current “war” against China, Italy, and Germany (once again). This war may not be one  of dropping bombs and killing people, but it is a war nevertheless…and it is just as dangerous, if not more so.

of dropping bombs and killing people, but it is a war nevertheless…and it is just as dangerous, if not more so.

After World War II, and after the disdain against the Germans faded, the hamburger reemerged. During that time, the invention claims also emerged. It is thought that the hamburger was invented between 1885 and 1904, but it is clearly the product of the early 20th century. The origin is under dispute. Some say it was invented in the United States and some say that it was invented in Germany. During the following 100 years, the hamburger spread throughout the world, and continued on until World War I when it became just a little too German.

In a war, good intel is crucial. The opposing armies always use codes in messages so that their plans are not known. Breaking codes is not an easy task, nor is it a quick task. During World War I, the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty was called Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (Old Building) (latterly NID25). The unit was formed in October 1914. It began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence, gave intercepts from the German radio station at Nauen, near Berlin, to Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, who constructed ciphers as a hobby.

In a war, good intel is crucial. The opposing armies always use codes in messages so that their plans are not known. Breaking codes is not an easy task, nor is it a quick task. During World War I, the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty was called Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (Old Building) (latterly NID25). The unit was formed in October 1914. It began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence, gave intercepts from the German radio station at Nauen, near Berlin, to Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, who constructed ciphers as a hobby.

Ewing began recruiting civilians such as William Montgomery, who was a translator of theological works from German, and Nigel de Grey, who was a publisher. During the war, the war Room 40 decrypted around 15,000 intercepted German communications from wireless and telegraph traffic. The section’s most notable work was when they intercepted and decoded the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico. This was the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War I, because it played a significant role in drawing the then-neutral United States into the conflict.

Room 40 operations began simply with the acquisition of a captured German naval codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), and maps (containing coded squares) that Britain’s Russian allies had passed on to the Admiralty. Before long it was playing a vital part in the intelligence industry. It all started when the Russians seized this material from the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg after it ran aground off the Estonian coast on August 26, 1914. The Russians recovered three of the four copies that the warship had carried. They retained two and passed the other to the British. In October 1914 the British also obtained the Imperial German Navy’s Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB), a codebook used by German naval warships, merchantmen, naval zeppelins and U-Boats. The Royal Australian Navy seized a copy from the Australian-German steamer Hobart on October 11th. Then, on November 30th, a British trawler recovered a safe from the sunken German destroyer S-119, in which was found the Verkehrsbuch (VB), the code used by the Germans to communicate with naval attachés, embassies and warships overseas. It was an amazing find. In March 1915 a British  detachment impounded the luggage of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a German agent in Persia and shipped it, unopened, to London, where the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall discovered that it contained the German Diplomatic Code Book, Code No. 13040.

detachment impounded the luggage of Wilhelm Wassmuss, a German agent in Persia and shipped it, unopened, to London, where the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall discovered that it contained the German Diplomatic Code Book, Code No. 13040.

The section retained “Room 40” as its informal name even though it expanded during the war and moved into other offices. Alfred Ewing directed Room 40 until May 1917, when direct control passed to Captain (later Admiral) Reginald ‘Blinker’ Hall, assisted by William Milbourne James. Although Room 40 successfully decrypted Imperial German communications throughout World War I, its function was compromised by the Admiralty’s insistence that all decoded information would only be analyzed by Naval specialists. This meant while Room 40 operators could decrypt the encoded messages they were not permitted to understand or interpret the information themselves. Whatever they couldn’t do, they accomplished a very great deal.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When all the lifeboats were launched, and the crew and remaining passengers knew the Titanic was surely going down, Lightoller and his fellow officers “all shook hands and said ‘Good-bye’” as they saw the last lifeboat off. Lightoller then dove into the frigid water from the bridge choosing to take his chances in the water, rather than the ship. Miraculously he managed to avoid being sucked down along with the massive ship. He clung to an nearby overturned lifeboat until the survivors were rescued. Lightoller was the last person pulled aboard the Carpathia and the highest-ranking officer to survive the wreck. One might imagine that surviving the greatest  maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

Following his survival of the shipwreck of Titanic, Lightoller went on to serve as a commanding officer of the Royal Navy during World War I, Lightoller was given command of his own torpedo boat. He was decorated twice for gallantry for his actions in combat, including sinking the German submarine UB-110. He emerged from the Great War as a full naval Commander. Lightoller retired after the war, but couldn’t leave the sea behind entirely. He and his wife bought their own boat in 1929. They called it Sundower and spent the next decade cruising around northern Europe and carrying out the occasional secret surveillance mission for the Admiralty when the Germans began preparing for war again.

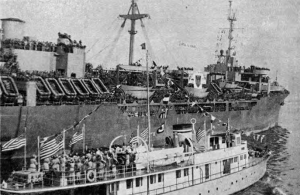

Though Lightoller was retired by the time World War II started, he provided and sailed as a volunteer on one of the “little ships” that played a part in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation. Rather than allow his motoryacht to be requisitioned by the Admiralty, he and his son Roger and a young Sea Scout named Gerald Ashcroft, crossed the English Channel in Sundowner to assist in the Dunkirk evacuation. The boat was licensed to carry just 21 passengers, but Lightoller and his crew brought back 127 servicemen. On the return journey, Lightoller evaded gunfire from enemy aircraft, using a technique described to him by his youngest son, Herbert, who had joined the RAF and been killed earlier in the war. Gerald Ashcroft later described the incident, “We attracted the attention of a Stuka dive bomber. Commander Lightoller stood up in the bow and I stood alongside the wheelhouse. Commander Lightoller kept his eye on the Stuka till the last second – then he sang out to me “Hard a port!” and I sang out to Roger and we turned very sharply. The bomb landed on our starboard side.” So, years after his first lifesaving event, Lightoller was once again saving lives in an emergency. Many people  would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

After the Second World War, Lightoller managed a small boatyard in Twickenham, West London, called Richmond Slipways, which built motor launches for the river police. Lightoller died of chronic heart disease on December 8, 1952, aged 78. He was a long-time pipe smoker, and he died during London’s Great Smog of 1952, which took the lives of many elderly people with breathing issues. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at the Commonwealth “Garden of Remembrance” at Mortlake Crematorium in Richmond, Surrey.

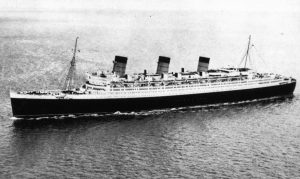

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

During the world wars, the military commandeered these cruise ships for troop transports, and also for munitions transports. It was not always safe for these ships to be carrying civilian passengers, as was seen with the sinking of the Lusitania, so after a time the cruise ships had to stop their civilian trips and become troop transports exclusively. They had to stop, because whether the ship had munitions on it or not, it was sunk with civilian passengers onboard.

At a time when there were no passenger planes, ocean liners provided the only pathway to cross the oceans. Once war in Europe had begun, many of the great ocean liners of the period withdrew from transatlantic crossings. However, they still remained at sea. Wartime saw ocean liners converted into troopships, carrying thousands of soldiers on a single trip, from bases in the United States to bases in the theaters in Europe, Africa, and Japan. Some of the most famous names in steamship history, including Mauretania, Olympic, Leviathan,  Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Of course, these ships faced the threat of submarine or airborne attack, so speed was the greatest defense the ship could have, but they couldn’t just start using the ships. These ships had to go through a process of preparation before they could be a transport ship. All of the items that were not needed for sustaining or berthing the maximum number of troops, were among the first things to go. Furniture, paintings, pianos, and everything else not needed for war would be removed and stored on land, to be returned to the ship after the war was over. The empty space was then filled with hammocks and cots for the soldiers to sleep on. They mounted guns on the decks to provide defensive capability. Of course, these liners could not act as a warship. They were just not designed for that, but a few well placed shots, might deter some of the smaller boats like U-boats from making a surface attack.

Camouflage was considered a critical part of the liners ability to survive in hostile waters. They applied “dazzle paint” to the hulls of these ocean liners. Oddly, the paint closely resembling zebra stripes!! They reasoned that alternating dark and light stripes would obscure the size, speed, heading, and type of ship when viewed from a distance. I can’t picture that exactly, and apparently it wasn’t very effective either. I guess all that it really did  was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

Following the war, and ship that survived their wartime duties was restored to its former look and feel so that it could continue with its pre-war duties. Unfortunately, many of these beautiful ocean liners were lost to enemy fire during the war. Sadly, there are no real examples of these wartime liners turned troop transports, but the Queen Mary is in dry dock in Long Beach, California. Visitors can take a tour, and get a real feel for those cramped quarters. Visitors can imagine the soldiers felt as they crossed the North Atlantic, knowing that their ship was a prized target for the enemy.

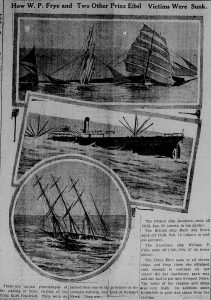

As is common with ships, the William P. Frye was a four-masted steel barque named after a US Republican politician of the same name, from the state of Maine. The ship was built by Arthur Sewall and Co of Bath, Maine in 1901. For a time, the ship had a great run…until 1915, that is. The ship sailed from Seattle, Washington on November 4, 1914, with a cargo of 189,950 US bushels of wheat. The ship and its cargo were bound for Queenstown, Falmouth, or Plymouth in the United Kingdom. In 1915 the United Kingdom was at war with Imperial Germany, but the United States was not enter the war yet and was officially neutral. It was early in the war, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous to sail the high seas.

As is common with ships, the William P. Frye was a four-masted steel barque named after a US Republican politician of the same name, from the state of Maine. The ship was built by Arthur Sewall and Co of Bath, Maine in 1901. For a time, the ship had a great run…until 1915, that is. The ship sailed from Seattle, Washington on November 4, 1914, with a cargo of 189,950 US bushels of wheat. The ship and its cargo were bound for Queenstown, Falmouth, or Plymouth in the United Kingdom. In 1915 the United Kingdom was at war with Imperial Germany, but the United States was not enter the war yet and was officially neutral. It was early in the war, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous to sail the high seas.

When the ship was near the coast of Brazil, the Imperial German Navy raider SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich overtook the William P. Frye on January 27, 1915. The Germans stopped and boarded the ship. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to have an enemy navy detain a ship I was on. You just never know what they are going to do. The William P. Frye was owned by the United States, and so a neutral ship. The ship should have been treated  as neutral. The problem the William P. Frye had is that the cargo was deemed a legitimate war target because the Germans believed it was bound for Britain’s armed forces. In reality, even detaining the ship was probably an act of war, but that never seemed to bother the Germans anyway.

as neutral. The problem the William P. Frye had is that the cargo was deemed a legitimate war target because the Germans believed it was bound for Britain’s armed forces. In reality, even detaining the ship was probably an act of war, but that never seemed to bother the Germans anyway.

Upon making his decision that the William P. Frye was a legitimate target, the captain of SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, Max Thierichens, ordered that William P. Frye’s cargo of wheat be thrown overboard. The captain and crew began to comply, most likely begrudgingly, and when the orders were not followed fast enough, he took the ship’s crew and passengers prisoner. Then he ordered the ship scuttled on January 28, 1915. The William P. Frye was the first American vessel sunk during World War I, and the United States wasn’t even in the war yet. The  owners of the ship, Arthur Sewall and Co, wanted damages for the sinking of the ship and presented a claim for $228,059.54, which would total $5,763,800 today. In all, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich scuttled eleven ships during their reign of terror. They stole coal and gold from their victims, which kept them going for a while, until they developed engine trouble.

owners of the ship, Arthur Sewall and Co, wanted damages for the sinking of the ship and presented a claim for $228,059.54, which would total $5,763,800 today. In all, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich scuttled eleven ships during their reign of terror. They stole coal and gold from their victims, which kept them going for a while, until they developed engine trouble.

In another act of war, Thierichens took the passengers and the crew captive. Women and children, were part of approximately 350 people taken prisoner from eleven different ships that SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich’s crew had searched and destroyed. I suppose the possible act of war was somewhat forgiven when all 350 were released on March 10, 1915, when the German raider had engine trouble, and docked Newport News, Virginia, but then again, what else could they do with them. Nevertheless, an outraged American government forced the Germans to apologize for the sinking, and of course, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich was detained in port.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

No one wanted to go to war with Japan, and it was going to take some work to drum up support for the unpopular war. The Russian government allowed a conference of the zemstvos to take the lead. A zemstvo was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 and carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. The first zemstvo laws went into effect in 1864. After the October Revolution the zemstvo system was shut down by the Bolsheviks and replaced with a multilevel system of workers’ and peasants’ councils…the regional governments instituted by Nicholas’s grandfather Alexander II, in St. Petersburg in November 1904. The demands for reform made at this congress went unmet and more radical socialist and workers’ groups decided to take a different tack.

Things exploded on January 22, 1905, when a group of workers led by the radical priest Georgy Apollonovich Gapon marched to the czar’s Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to make their demands. the imperial forces

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

During World War II, transferring intel from the spies in France…the resistance, was difficult. To fly a plane through the anti-aircraft fire was dangerous, and often not successful. To send a spy on foot was not only something that would take far too long, not to mention the possibility of being caught. The intelligence community had to come up with a way to get the information to the generals and to the president quickly…and it had to be a way to succeed without massive loss of life.

During World War II, transferring intel from the spies in France…the resistance, was difficult. To fly a plane through the anti-aircraft fire was dangerous, and often not successful. To send a spy on foot was not only something that would take far too long, not to mention the possibility of being caught. The intelligence community had to come up with a way to get the information to the generals and to the president quickly…and it had to be a way to succeed without massive loss of life.

After much discussion, they happened on the idea of using homing pigeons to take messages back and forth between the spies, the resistance, and even the citizens of France. The idea was to drop the pigeons in a cage that was parachuted into the country. Once the pigeons were on the ground, the people were to write notes on small pieces of paper, place it in the canister attached to the pigeon’s leg, and release the bird to fly home. These pigeons were a huge help to the war effort, and were used in at least two wars.

Years later, a couple stumbled onto a capsule containing a cryptic note dated to either 1910 or 1916. Jade Halaoui was hiking in the fields near Alsace, France this September 2020. Ahead of him, he noticed something shiny. Upon further inspection, he found a small capsule partially buried in the ground and opened it. Inside was a note, written in German in cursive script by a Prussian military officer. Most likely the canister has been attached to a carrier pigeon, but never reached its destination. Halaoui and his partner, Juliette, took the artifact to the Linge Memorial Museum in Orbey.

A curator took a look at the canister and it’s note. He sat down at a table and delicately lifted the frail-looking slip of paper with tweezers. The note was very old, thin, and worn. It was written in spidery German cursive script. It was determined that the message was likely sent by a Prussian infantry officer via carrier pigeon around the onset of World War I. Dominique Jardy, curator at the Linge museum, told one reporter that the note was written in looping handwriting that is difficult to decipher, however, while the date clearly reads July 16…the year could be interpreted as 1910 or 1916. World War I took place between 1914 and 1918. With that in mind, it was concluded that the note was likely written 1916.

Jardy enlisted a German friend to help him translate the note. The note read in part: “Platoon Potthof receives fire as they reach the western border of the parade ground, platoon Potthof takes up fire and retreats after a while. In Fechtwald half a platoon was disabled. Platoon Potthof retreats with heavy losses.” The message, which was addressed to a senior officer. It appears that the infantryman was based in Ingersheim. The note refers to a military training ground, which lead Jardy to think that the note likely refers to a practice maneuver, not actual warfare. If this was the case, and the note was written in 1910, it could refer to a preparation for war. If it was written in 1916, this could have been training in anticipation of a long time of war.

Jardy mentioned that military officials typically sent multiple pigeons with the same message to ensure that crucial information reached its destination. One can only hope that is true, because if this was vital information,

and it did not get through, finding it now is unfortunately more than a century too late. Halaoui discovered the long-lost message just a few hundred yards from its site of origin, so Jardy suspects that this capsule slipped off the homing pigeon’s leg early in its journey. I hope that is true, because some of these pigeons were shot down. Others were caught by the hungry citizens and used for food, but some made it home and they were heroes of war too, because they brought important intel to the Allies.

and it did not get through, finding it now is unfortunately more than a century too late. Halaoui discovered the long-lost message just a few hundred yards from its site of origin, so Jardy suspects that this capsule slipped off the homing pigeon’s leg early in its journey. I hope that is true, because some of these pigeons were shot down. Others were caught by the hungry citizens and used for food, but some made it home and they were heroes of war too, because they brought important intel to the Allies.

Weapons of warfare have changed over the years, but one of the strangest fighting systems was during World War I, when the planes were not as sophisticated as planes are today. They were slow and at that time, they did not have the guns attached to the planes. Of course they were usually two-seaters, so unlike the World War II planes that had a pilot exclusively assigned to fly the plane, both occupants of the plane had to shoot, or they would be shot down. That was how war was. Kill or be killed.

Weapons of warfare have changed over the years, but one of the strangest fighting systems was during World War I, when the planes were not as sophisticated as planes are today. They were slow and at that time, they did not have the guns attached to the planes. Of course they were usually two-seaters, so unlike the World War II planes that had a pilot exclusively assigned to fly the plane, both occupants of the plane had to shoot, or they would be shot down. That was how war was. Kill or be killed.

The problem of not having guns attached to the plane was really one of control. There was the problem of controlling the plane with shots being fired all around you and no protection in the open cockpit. Then there was controlling the guns in the wind of flight. Not to mention the shots being fired at the open cockpit. The guns the soldiers had on these early planes were carbines and pistols…to take down a war plane…yikes. Of course, there  were other problems too. Trying to shoot at the enemy from the cockpit of the plane, the soldier had to be careful not to shoot off the propeller. That would definitely be problematic.

were other problems too. Trying to shoot at the enemy from the cockpit of the plane, the soldier had to be careful not to shoot off the propeller. That would definitely be problematic.

Really, I can’t imagine being a pilot in that war era. You would really be taking your life in your own hands…even more so than the men who flew in later eras, who were also in grave danger, but maybe a little less so. Imagine being the co-pilot in the plane when your pilot is waving his gun around trying to hit the planes flying around you. If the soldier shooting could shoot off the propeller, they could just as easily shoot the other occupant of the plane. I suppose that the pilots fighting in World War I would say that they were just doing their duty, but it seems to me that their “duty” took great courage. Of course, any soldier, no matter what their duty, does their duty, and it always takes great courage. Any soldier  must exhibit great courage in battle. There is no way to go into battle and not be concerned for your safety. And thankfully, as time goes on, weapons of warfare are getting more advanced at being effective, while protecting the soldier in the fight.

must exhibit great courage in battle. There is no way to go into battle and not be concerned for your safety. And thankfully, as time goes on, weapons of warfare are getting more advanced at being effective, while protecting the soldier in the fight.

Of course, those old biplanes had some advantages too. The open cockpit design allowed for easy spying. They could also see the enemy better, and it was easier to drop bombs in those planes, but the later planes made for easier shooting with the attached gun, multiple guns, and the nose guns of the men below the pilots. I’m thankful for the many improvements that have made it easier for our soldiers to come home alive.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

The men who built these trains became so skilled at their work, that on December 10 – 11, 1891, the Great Eastern Railway’s Stratford Works built one of these locomotives and had it “in steam” with a coat of grey primer in 9 hours 47 minutes. That feat remains a world record. The locomotive then went off to run 36,000 miles on Peterborough to London coal  trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

Because of their light weight the locomotives were given the Route Availability (RA) number 1, indicating that they could work over nearly all routes. Steam engine trains are generally safe, and still used to this day, although not in modern transport situations. Still, they can pose a problem in certain situations. Just like boilers in homes and commercial buildings, too much pressure that is not alleviated presents a huge danger.

On September 25, 1900, at 8:45am, GER Class Y14 0-6-0 locomotive Number 522, just a year old at the time,  stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

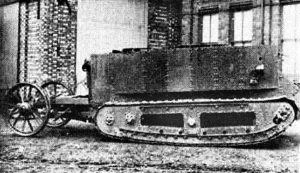

When I think of a tank, my thoughts go to an almost indestructible war machine, and I’m sure many people would agree with me. The tank was first introduced on September 6, 1915 in response to the trench warfare era of World War I. A British army colonel named Ernest Swinton and secretary of the Committee for Imperial Defense, William Hankey, championed the idea of an armored vehicle with “conveyor-belt-like tracks” over its wheels that could break through enemy lines and traverse difficult territory. It was a great idea, but the prototype tank nicknamed Little Willie manufactured in England was far from an overnight success. The tank was heavy, weighing in at 14 tons, but the big problem was that it got stuck in trenches and crawled over rough terrain at only two miles per hour. A tank isn’t much good if it has to be rescued, instead of rescuing the soldiers. It was also slow, and it became overheated and couldn’t cross the trenches. A second prototype, known as “Big Willie,” was produced. By 1916, this armored vehicle was deemed ready for battle and made its debut at the First Battle of the Somme near Courcelette, France, on September 15 of that year. Known as the Mark I, this first batch of tanks was hot, noisy and unwieldy and suffered mechanical malfunctions on the battlefield. Still, people began to realize the tank’s potential. Further design improvements were made and at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, 400 Mark IV’s proved much more successful than the Mark I, capturing 8,000 enemy troops and 100 guns.

When I think of a tank, my thoughts go to an almost indestructible war machine, and I’m sure many people would agree with me. The tank was first introduced on September 6, 1915 in response to the trench warfare era of World War I. A British army colonel named Ernest Swinton and secretary of the Committee for Imperial Defense, William Hankey, championed the idea of an armored vehicle with “conveyor-belt-like tracks” over its wheels that could break through enemy lines and traverse difficult territory. It was a great idea, but the prototype tank nicknamed Little Willie manufactured in England was far from an overnight success. The tank was heavy, weighing in at 14 tons, but the big problem was that it got stuck in trenches and crawled over rough terrain at only two miles per hour. A tank isn’t much good if it has to be rescued, instead of rescuing the soldiers. It was also slow, and it became overheated and couldn’t cross the trenches. A second prototype, known as “Big Willie,” was produced. By 1916, this armored vehicle was deemed ready for battle and made its debut at the First Battle of the Somme near Courcelette, France, on September 15 of that year. Known as the Mark I, this first batch of tanks was hot, noisy and unwieldy and suffered mechanical malfunctions on the battlefield. Still, people began to realize the tank’s potential. Further design improvements were made and at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, 400 Mark IV’s proved much more successful than the Mark I, capturing 8,000 enemy troops and 100 guns.

As with any new invention, the tank had a few “bugs” to be worked out. Still, I doubt if that did much to assuage the fears of the men in the tanks when they got stuck in the trenches. Tanks are supposed to be able to withstand gun shots and shrapnel, but would the tank be able to do so. After all, tanks weren’t supposed to get stuck either, so just how trustworthy was the armor plating. A tank that gets stuck is really just a “sitting duck.” Nevertheless, improvements were made to the original prototype and eventually tanks completely transformed military battlefields.

Trench warfare of World War I truly was brutal, almost more for the men in the trenches than anyone else.  Finally, the men appealed to British navy minister Winston Churchill, who believed in the concept of a “land boat” and organized a Landships Committee to begin developing a prototype. To keep the project secret from enemies, production workers were reportedly told the vehicles they were building would be used to carry water on the battlefield…alternate theories suggest the shells of the new vehicles resembled water tanks. Either way, the new vehicles were shipped in crates labeled “tank” and the name stuck. Tanks rapidly became an important military weapon. During World War II, they played a prominent role across numerous battlefields. The tanks potential was finally an accepted fact.

Finally, the men appealed to British navy minister Winston Churchill, who believed in the concept of a “land boat” and organized a Landships Committee to begin developing a prototype. To keep the project secret from enemies, production workers were reportedly told the vehicles they were building would be used to carry water on the battlefield…alternate theories suggest the shells of the new vehicles resembled water tanks. Either way, the new vehicles were shipped in crates labeled “tank” and the name stuck. Tanks rapidly became an important military weapon. During World War II, they played a prominent role across numerous battlefields. The tanks potential was finally an accepted fact.