United States

World War II had dragged on for almost six years, when the United States took things to the next, and as it turns out, final level. For quite some time, Japan had been one of the forces to be reckoned with. Now, with so much new technology, a plan has begun to form to put an end to this war, once and for all. The Japanese had no idea what was coming…how the 6th of August, 1945 would change things forever.

World War II had dragged on for almost six years, when the United States took things to the next, and as it turns out, final level. For quite some time, Japan had been one of the forces to be reckoned with. Now, with so much new technology, a plan has begun to form to put an end to this war, once and for all. The Japanese had no idea what was coming…how the 6th of August, 1945 would change things forever.

That August 6th in 1945 dawned like any other day, but at it’s end, the world would find that everything had changed. The power to destroy whole cities in an instant was in our hands. At 8:16am, an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The ensuing explosion wiped out 90 percent of the city and immediately killed 80,000 people. Tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, a second B-29 dropped another  A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. With these two events, it was very clear that the nations had the ability to bring mass destruction. Hopefully, they would also have the compassion, not to do it.

A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. With these two events, it was very clear that the nations had the ability to bring mass destruction. Hopefully, they would also have the compassion, not to do it.

With such a show of power, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender to the Japanese people in World War II in a radio address on August 14th, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb” as the reason Japan could no longer stand against the Allies. I’m sure the war-ravaged people of Japan were almost relieved. Of course, that meant that they did not know what their future would bring, but the recent past hadn’t been so great either, so they didn’t have too much to lose really.

Japan’s War Council, urged by Emperor Hirohito, submitted a formal declaration of surrender to the Allies, on August 10, but the fighting continued between the Japanese and the Soviets in Manchuria and between the Japanese and the United States in the South Pacific. During that time, a Japanese submarine attacked the Oak Hill, an American landing ship, and the Thomas F. Nickel, an American destroyer, both east of Okinawa. On August 14, when Japanese radio announced that an Imperial Proclamation was coming soon, in which Japan would accept the terms of unconditional surrender drawn up at the Potsdam Conference. The news did not go over well. More than 1,000 Japanese soldiers stormed the Imperial Palace in an attempt to find the

proclamation and prevent its being transmitted to the Allies. Soldiers still loyal to Emperor Hirohito held off the attackers. That evening, General Anami, the member of the War Council most adamant against surrender, committed suicide. His reason was to atone for the Japanese army’s defeat, and he refused to hear his emperor speak the words of surrender. I guess the surrender was not a relief to everyone.

proclamation and prevent its being transmitted to the Allies. Soldiers still loyal to Emperor Hirohito held off the attackers. That evening, General Anami, the member of the War Council most adamant against surrender, committed suicide. His reason was to atone for the Japanese army’s defeat, and he refused to hear his emperor speak the words of surrender. I guess the surrender was not a relief to everyone.

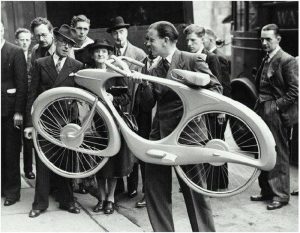

Today it would be worth about $4750. Would you pay that much for a bicycle? I don’t think I would, but then I don’t suppose I would be buying a bicycle called the Spacelander. Still, if I was, $4750 would be the asking price, or something close to that number. The Spacelander was created by Benjamin Bowden, who was born June 3, 1906. He was a British industrial designer, whose specialty was automobiles and bicycles. He received violin training at Guildhall, and completed a course in engineering at Regent. Bowden designed the coachwork of Healey’s Elliott, an influential British sports car.

Today it would be worth about $4750. Would you pay that much for a bicycle? I don’t think I would, but then I don’t suppose I would be buying a bicycle called the Spacelander. Still, if I was, $4750 would be the asking price, or something close to that number. The Spacelander was created by Benjamin Bowden, who was born June 3, 1906. He was a British industrial designer, whose specialty was automobiles and bicycles. He received violin training at Guildhall, and completed a course in engineering at Regent. Bowden designed the coachwork of Healey’s Elliott, an influential British sports car.

In 1925 Bowden began working as an automobile designer for the Rootes Group. By the late 1930s, Bowden was the chief body engineer for the Humber car factory in Coventry. During World War II, his design of an armored car was used by Winston Churchill and George VI for their protection. In 1945, he left the Rootes Group, and with partner John Allen, formed his own design company in Leamington Spa. The studio was one of the first such design firms in Britain. Bowden designed the body of Healey’s Elliott in 1947. It was the first British car to break the 100 mile per hour barrier. Working with Achille Sampietro who created the chassis, Bowden drew the initial design for the auto directly onto the walls of his house. Unusual…yes, but it worked for him, I guess. Shortly before his departure to the United States Bowden penned a sketch design for a two-seater sports racing prototype, the Zethrin Rennsport, being developed by Val Zethrin. This used the same wheelbase as the short-chassis Squire Sports, and was dressed in a contemporary, streamlined body. This design theme was carried through to his future work on the early Chevrolet Corvette and Ford Thunderbird.

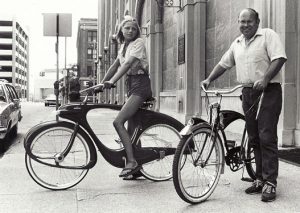

He went on to design the Spacelander in 1946. It was a space-age looking bicycle, that was ahead of its time, since space travel wouldn’t occur for two decades. It’s not that the Spacelander would ever be used in space, but rather the design that seemed space-like. Bowden called the bicycle the Classic. In the early or mid 1950s, Bowden moved to Michigan, in the United States. While in Muskegon, Michigan in 1959, he met with Joe Kaskie, of the George Morrell Corporation, a custom molding company. Kaskie suggested molding the bicycle in fiberglass instead of aluminum, but the fiberglass frame was relatively fragile, and its unusual nature made it difficult to market to established bicycle distributors. Although he retained the futuristic appearance of the Classic, Bowden abandoned the hub dynamo, and replaced the drive-train with a more common sprocket-chain assembly. The new name, Spacelander, was chosen to capitalize on interest in the Space Race. Financial

troubles from the distributor forced Bowden to rush development of the Spacelander, which was released in 1960 in five colors: Charcoal Black, Cliffs of Dover White, Meadow Green, Outer Space Blue, and Stop Sign Red. The bicycle was priced at $89.50, which made it one of the more expensive bicycles on the market. Only 522 Spacelander bicycles were shipped before production was stopped, although more complete sets of parts were manufactured. In more recent years, the Spacelander has become a collector’s item…hence the price tag.

troubles from the distributor forced Bowden to rush development of the Spacelander, which was released in 1960 in five colors: Charcoal Black, Cliffs of Dover White, Meadow Green, Outer Space Blue, and Stop Sign Red. The bicycle was priced at $89.50, which made it one of the more expensive bicycles on the market. Only 522 Spacelander bicycles were shipped before production was stopped, although more complete sets of parts were manufactured. In more recent years, the Spacelander has become a collector’s item…hence the price tag.

With the arrival of the 50th anniversary of the landing on the moon, on July 20, 2019, many people have been reviewing old footage and books about the event. I came across a book that caught my eye on Audible. The book, The Man Who Knew The Way To The Moon, by Todd Zwillich wasn’t exactly about the moon landing, but rather how it became possible. The book begins with Russia beating the United States to the punch when they sent a man Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961. As short as the flight was…just 89 minutes…it was still an embarrassment to the United States who felt they should have been first.

With the arrival of the 50th anniversary of the landing on the moon, on July 20, 2019, many people have been reviewing old footage and books about the event. I came across a book that caught my eye on Audible. The book, The Man Who Knew The Way To The Moon, by Todd Zwillich wasn’t exactly about the moon landing, but rather how it became possible. The book begins with Russia beating the United States to the punch when they sent a man Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961. As short as the flight was…just 89 minutes…it was still an embarrassment to the United States who felt they should have been first.

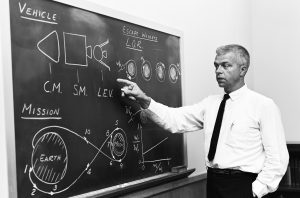

In answer to the Soviet space flight, President Kennedy challenged NASA to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade. NASA sort of panicked. Yes, they had been thinking about a moon landing…and some remote point down the road, but they were nowhere near ready to go them by the end of the decade. Nevertheless, they began to explore ideas to make it happen. One of those people who had been considering a way to make the landing possible. By this time, no one doubted the ability to go into space, and to safely return to earth. Landing on the moon was a different story.

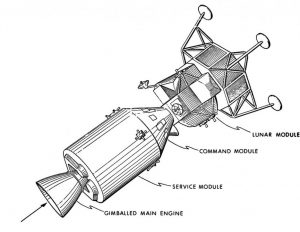

The widely accepted method of landing on the moon was to have the original rocket back onto the moon, carrying enough fuel to take off again and return to Earth. A man named John Houbolt thought that was…well, simply impossible. Now, I’m no aeronautical engineer, like Houbolt was, and maybe I have the advantage of  knowing about the past space exploration victories, but when I think about three astronauts backing a 90 foot high, fully fueled rocket onto the moon…all I can say is, “That’s ludicrous!!” People often say that an idea doesn’t take a rocket scientist, and it this case, maybe it shouldn’t be a rocket scientist, but rather an aeronautical engineer.

knowing about the past space exploration victories, but when I think about three astronauts backing a 90 foot high, fully fueled rocket onto the moon…all I can say is, “That’s ludicrous!!” People often say that an idea doesn’t take a rocket scientist, and it this case, maybe it shouldn’t be a rocket scientist, but rather an aeronautical engineer.

John Houbolt, kept saying and trying to be heard, that it wouldn’t work, but he had a plan that would…Lunar Orbit Rendezvous or LOR. In Houbolt’s design, a smaller lunar module would land on the moon while the command module waited above. Then the Lunar module would take of and dock with the command module for the trip back to Earth. It is the way we know did work, because we have the advantage of time, but the scientists and engineers at NASA would not listen. One man, Max Faget, an immigrant from British Honduras, who designed the Mercury module, actually stood up at a meeting where Houbolt was presenting his idea, and yelled at the group, saying, “His figures lie! He doesn’t know what he’s talking about!” Houbolt was horribly humiliated, and he never forgot the incident. He didn’t let it stop him either. In the end, as Faget spent many hours trying desperately to make his own figures work, so  that a rocket could back onto the moon, he finally had to admit defeat. He called John Houbolt, and conceded the lunar landing design to Houbolt’s design, which was, as we all know, completely successful, because after all, his figures did not lie, and he did know what he was talking about. It was a great moment in history, and in Houbolt’s life, except for the fact that no one knew that the successful landing was his design. While the Lunar landing, 50 years ago was an amazing accomplishment, I find it quite sad that it took so many years for the world to know about how one man’s refusal to give up, actually made Lunar landing possible. We owe John Houbolt a great debt of gratitude, and it is more than 50 years overdue. Now that’s ludicrous!!

that a rocket could back onto the moon, he finally had to admit defeat. He called John Houbolt, and conceded the lunar landing design to Houbolt’s design, which was, as we all know, completely successful, because after all, his figures did not lie, and he did know what he was talking about. It was a great moment in history, and in Houbolt’s life, except for the fact that no one knew that the successful landing was his design. While the Lunar landing, 50 years ago was an amazing accomplishment, I find it quite sad that it took so many years for the world to know about how one man’s refusal to give up, actually made Lunar landing possible. We owe John Houbolt a great debt of gratitude, and it is more than 50 years overdue. Now that’s ludicrous!!

Some of the biggest defeats in any war come from underestimating the enemy or refusing to believe the facts. In the case of Japan it was a little of both. The security of the Marianas Islands, in the western Pacific, was vital to Japan, which had air bases on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. The United States troops were already battling the Japanese on Saipan, since their arrival there on June 15, 1944. Any further intrusion would leave the Philippine Islands, and Japan itself, vulnerable to US attack. The Japanese needed to maintain their security in the Marianas Islands.

Some of the biggest defeats in any war come from underestimating the enemy or refusing to believe the facts. In the case of Japan it was a little of both. The security of the Marianas Islands, in the western Pacific, was vital to Japan, which had air bases on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. The United States troops were already battling the Japanese on Saipan, since their arrival there on June 15, 1944. Any further intrusion would leave the Philippine Islands, and Japan itself, vulnerable to US attack. The Japanese needed to maintain their security in the Marianas Islands.

The US Fifth Fleet, commanded by Admiral Raymond Spruance, was on its way northwest from the Marshall Islands. Their mission was to provide backup for the invasion of Saipan and the rest of the Marianas. Whether he knew what was going on or not,  Japanese Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo, decided to challenge the American fleet. He ordered 430 of his planes, launched from aircraft carriers, to attack. The greatest carrier battle of the war was about to begin. The United States picked up the Japanese craft on radar and shot down more than 300 aircraft and sunk two Japanese aircraft carriers. By comparison, the United States only lost 29 of their own planes in the process. Strangely, Admiral Ozawa, believed that his missing planes had landed at their Guam air base. He maintained his position in the Philippine Sea, allowing for a second attack of US carrier-based fighter planes. He made his men sitting ducks!! The secondary attack, commanded by Admiral Mitscher, shot down an additional 65 Japanese planes and sink another carrier. In total, the Japanese lost 480 aircraft…about three-quarters of its total aircraft, not to mention most of its crews. American would dominate the Marianas Islands, and Japan was in deep trouble. The battle was later described as a “turkey shoot.”

Japanese Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo, decided to challenge the American fleet. He ordered 430 of his planes, launched from aircraft carriers, to attack. The greatest carrier battle of the war was about to begin. The United States picked up the Japanese craft on radar and shot down more than 300 aircraft and sunk two Japanese aircraft carriers. By comparison, the United States only lost 29 of their own planes in the process. Strangely, Admiral Ozawa, believed that his missing planes had landed at their Guam air base. He maintained his position in the Philippine Sea, allowing for a second attack of US carrier-based fighter planes. He made his men sitting ducks!! The secondary attack, commanded by Admiral Mitscher, shot down an additional 65 Japanese planes and sink another carrier. In total, the Japanese lost 480 aircraft…about three-quarters of its total aircraft, not to mention most of its crews. American would dominate the Marianas Islands, and Japan was in deep trouble. The battle was later described as a “turkey shoot.”

Not long after this battle at sea, US Marine divisions penetrated farther into the island of Saipan. Two of the  Japanese commanders on the island, Admiral Nagumo and General Saito, both committed suicide in an attempt to rally the remaining Japanese forces. I can’t imagine how that would inspire the forces. It was an act that can only be understood by a sick mind, but their plan worked. Those forces also committed a virtual suicide as they attacked the Americans’ lines, losing 26,000 men compared with 3,500 lost by the United States. Within another month, the islands of Tinian and Guam were also captured by the United States. Due to the disgrace, the Japanese government of Premier Hideki Tojo resigned at this stunning defeat, in what many have described as the turning point of the war in the Pacific.

Japanese commanders on the island, Admiral Nagumo and General Saito, both committed suicide in an attempt to rally the remaining Japanese forces. I can’t imagine how that would inspire the forces. It was an act that can only be understood by a sick mind, but their plan worked. Those forces also committed a virtual suicide as they attacked the Americans’ lines, losing 26,000 men compared with 3,500 lost by the United States. Within another month, the islands of Tinian and Guam were also captured by the United States. Due to the disgrace, the Japanese government of Premier Hideki Tojo resigned at this stunning defeat, in what many have described as the turning point of the war in the Pacific.

The Japanese had a tendency to be sneaky about their weapons of warfare, and their attack plans, as we know from Pearl Harbor. One such well kept secret was the Hiryu…which means Flying Dragon. The ship was a modified Soryu design that was built exclusively for the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Soryu, which means Blue Dragon, was built first, and because of the heavy modifications, the Hiryu was almost considered to be a separate class of ship. Hiryu had a displacement of 17,600 tons, length of 746 feet 1 inch, beam of 73 feet 2 inches, draft of 25 feet 7 inches and a speed of 34 knots. Built in 1931, “these two ships became prototypes for almost all subsequent Japanese carriers. They had continuous flight deck, two-level hangar, small island superstructure, two deflexed down and aft funnels and three elevators. As a whole ship design (within the limits of displacement assigned on it) has appeared rather successful, harmoniously combining high speed with strong AA armament and impressive number of air group.” The Hiryu, unlike the small height hangar levels of the Soryu, was built to an advanced design. “Her freeboard height was increased by one deck, island was transferred to a port side (Hiryu became second after Akagi and last Japanese carrier with an island on a port side). Breadth of a flight deck was increased on 1m, a fuel stowage on 20%. She had a little strengthened protection: belt thickness abreast machinery raised to 48mm.”

The Japanese had a tendency to be sneaky about their weapons of warfare, and their attack plans, as we know from Pearl Harbor. One such well kept secret was the Hiryu…which means Flying Dragon. The ship was a modified Soryu design that was built exclusively for the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Soryu, which means Blue Dragon, was built first, and because of the heavy modifications, the Hiryu was almost considered to be a separate class of ship. Hiryu had a displacement of 17,600 tons, length of 746 feet 1 inch, beam of 73 feet 2 inches, draft of 25 feet 7 inches and a speed of 34 knots. Built in 1931, “these two ships became prototypes for almost all subsequent Japanese carriers. They had continuous flight deck, two-level hangar, small island superstructure, two deflexed down and aft funnels and three elevators. As a whole ship design (within the limits of displacement assigned on it) has appeared rather successful, harmoniously combining high speed with strong AA armament and impressive number of air group.” The Hiryu, unlike the small height hangar levels of the Soryu, was built to an advanced design. “Her freeboard height was increased by one deck, island was transferred to a port side (Hiryu became second after Akagi and last Japanese carrier with an island on a port side). Breadth of a flight deck was increased on 1m, a fuel stowage on 20%. She had a little strengthened protection: belt thickness abreast machinery raised to 48mm.”

Hiryu took part in Japanese invasion of French Indochina (Now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) in mid 1940s, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Wake Island. The ship became a great enemy of the Allies. Then, along with three other fleet carriers, Hiryu participated in the Battle of Midway Atoll in North Pacific Ocean in June 1942. Initially, the Japanese forces managed to bombard US forces on the atoll. It didn’t look good for the  Allies, but on June 4, 1942, the Japanese aircraft carriers were attacked by dive-bomber aircraft from USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown, USS Hornet, and Midway Atoll. Hiryu was hit and severely crippled, and was set on fire. Japanese destroyer Makigumo torpedoed Hiryu on June 5, 1942 at 05:10 am, because she could not be salvaged. Only 39 men survived as after 4 hours, she sank with bodies of 389 men. Three other Japanese carriers were also sunk during the Battle of Midway. It was a battle that brought Japan’s first naval defeat since the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits in 1863. It was a great day for the Allies.

Allies, but on June 4, 1942, the Japanese aircraft carriers were attacked by dive-bomber aircraft from USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown, USS Hornet, and Midway Atoll. Hiryu was hit and severely crippled, and was set on fire. Japanese destroyer Makigumo torpedoed Hiryu on June 5, 1942 at 05:10 am, because she could not be salvaged. Only 39 men survived as after 4 hours, she sank with bodies of 389 men. Three other Japanese carriers were also sunk during the Battle of Midway. It was a battle that brought Japan’s first naval defeat since the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits in 1863. It was a great day for the Allies.

The current generation of kids probably have no idea what a phone booth is, besides maybe a place for Superman to change into his costume. From the time phones first became something that was provided to the public for a fee, phone booths became a common sight on city streets. Then in the 1950s, a new fad began. Much like the fad of stuffing as many people as possible into a car, people decided to stuff as many people as possible into a phone booth. My guess is that like most of these strange fads, this one too,

The current generation of kids probably have no idea what a phone booth is, besides maybe a place for Superman to change into his costume. From the time phones first became something that was provided to the public for a fee, phone booths became a common sight on city streets. Then in the 1950s, a new fad began. Much like the fad of stuffing as many people as possible into a car, people decided to stuff as many people as possible into a phone booth. My guess is that like most of these strange fads, this one too,  was practiced mostly by young people.

was practiced mostly by young people.

Phone booth stuffing first gained popularity outside the United States, but once it arrived stateside, in spring 1959, kids couldn’t help but join in. Basically, people would cram their bodies into the narrow spaces like sardines in a can. Some adopted other methods, such as stacking themselves horizontally. Just imagine being the guy on the bottom of the stack. All I can say is, “Hurry up, because I can’t breathe!!”

As with so many other crazy fad, phone booth stuffing became something to set a world record for. People began trying to outdo the prior record. The word record for phone-booth stuffing came in March 1959, when 25 people in South Africa piled into a booth. I can’t imagine how they could possibly fit 25 people in a phone booth, but while they were all in there, the phone rang. Of course, nobody answered the phone, because nobody could move enough to reach it. Sadly, the trend died by the end of 1959. Of course, that doesn’t mean that some of the other stuffing trends didn’t continue. I think people are still stuffing as many people as they can into a car. I just hope they don’t try to drive that way.

As with so many other crazy fad, phone booth stuffing became something to set a world record for. People began trying to outdo the prior record. The word record for phone-booth stuffing came in March 1959, when 25 people in South Africa piled into a booth. I can’t imagine how they could possibly fit 25 people in a phone booth, but while they were all in there, the phone rang. Of course, nobody answered the phone, because nobody could move enough to reach it. Sadly, the trend died by the end of 1959. Of course, that doesn’t mean that some of the other stuffing trends didn’t continue. I think people are still stuffing as many people as they can into a car. I just hope they don’t try to drive that way.

These days we don’t usually think much about trains as a form of transportation, but in 1869, they were the latest in modern travel. The United States is a large country, and it took months to travel across it with a horse drawn wagon. Travel was so time consuming, that most people could not take the necessary time off from their jobs and lives to go to visit family that had moved west, or those who stayed in the east. Enter the train.

These days we don’t usually think much about trains as a form of transportation, but in 1869, they were the latest in modern travel. The United States is a large country, and it took months to travel across it with a horse drawn wagon. Travel was so time consuming, that most people could not take the necessary time off from their jobs and lives to go to visit family that had moved west, or those who stayed in the east. Enter the train.

Trains could take people to far away destinations much faster, and cheaper…but there was still one problem…train tracks. The trains could only go as far as the tracks did, and the work of building tracks was a back breaking job. Nevertheless, 150 years ago, on this day, May 10, 1869, the presidents of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads meet in Promontory, Utah. There they drove a ceremonial last spike into a rail line that connects their railroads. This made transcontinental railroad travel possible for the first time in United States history.

Now 150 years later, on of the trains that rode those rails in those days is back on the rails. The locomotives were called “Big Boys” and they certainly were. “It’s longer than two city buses, weighs more than a Boeing 747 fully loaded with passengers and can pull 16 Statues of Liberty over a mountain.” The refurbished Big Boy is the number 4014 steam locomotive that rolled out of a Union Pacific restoration shop in Cheyenne this past weekend for a big debut after five years of restoration. It then headed toward Utah as part of a yearlong tour to commemorate the Transcontinental Railroad’s 150th anniversary. If you have a chance, I would highly recommend that you get a copy of the schedule and plan to go see it. We are planning to, for sure.

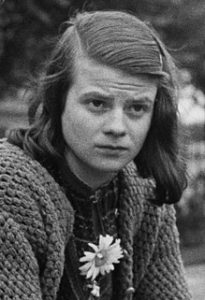

When we think of heroes during the Nazi years, we think mostly of men, but there were a few women who were real heroes too. One such woman, Sophia Magdalena Scholl, who was born on May 9, 1921, was a German student, who was also a serious anti-Nazi political activist. She was active within the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. Scholl was the fourth of six children born to Magdalena (Müller) and liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic Robert Scholl. Her father was the mayor of her hometown of Forchtenberg am Kocher in the Free People’s State of Württemberg, at the time of her birth.

When we think of heroes during the Nazi years, we think mostly of men, but there were a few women who were real heroes too. One such woman, Sophia Magdalena Scholl, who was born on May 9, 1921, was a German student, who was also a serious anti-Nazi political activist. She was active within the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. Scholl was the fourth of six children born to Magdalena (Müller) and liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic Robert Scholl. Her father was the mayor of her hometown of Forchtenberg am Kocher in the Free People’s State of Württemberg, at the time of her birth.

Scholl was brought up in the Lutheran church. She entered junior or grade school at the age of seven, and was considered an intelligent child who learned easily. Her childhood was a happy and carefree one. In 1930, the family moved to Ludwigsburg and then two years later to Ulm where her father had a business consulting office. These were definitely the best years of her life.

In 1932, after Scholl started attending a secondary school for girls, at the age of twelve, she chose to join the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls), as did most of her classmates. It was as common as joining the girl scouts was in the United States. Her initial enthusiasm gradually gave way to criticism. She was aware of the dissenting political views of her father, friends, and some teachers. Even her own brother Hans, who once eagerly participated in the Hitler Youth program, became entirely disillusioned with the Nazi Party. Sophia was quickly learning of the horrors of Hitler and his Nazi regime. Political attitude had become an essential criterion in her choice of friends. The arrest of her brothers and friends in 1937 for participating in the German Youth Movement left a strong impression on her.

In 1943, with the Nazi movement in full swing, Sophia and her brother, Hans were at the University of Munich distributing anti-war leaflets when they were arrested and charged with high treason. Of course, handing out  anti-war leaflets in the United States would never be considered cause for a high treason conviction, but then Sophia and her brother did not live in the United States. In the People’s Court before Judge Roland Freisler on 22 February 1943, Scholl was recorded as saying these words, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare express themselves as we did.” There was no testimony allowed for the defendants; this was their only defense. The brother and sister were subsequently convicted of the high treason charges, and as a result, were executed by guillotine on February 22, 1943. Since the 1970s, Scholl has been extensively commemorated for her anti-Nazi resistance work.

anti-war leaflets in the United States would never be considered cause for a high treason conviction, but then Sophia and her brother did not live in the United States. In the People’s Court before Judge Roland Freisler on 22 February 1943, Scholl was recorded as saying these words, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare express themselves as we did.” There was no testimony allowed for the defendants; this was their only defense. The brother and sister were subsequently convicted of the high treason charges, and as a result, were executed by guillotine on February 22, 1943. Since the 1970s, Scholl has been extensively commemorated for her anti-Nazi resistance work.

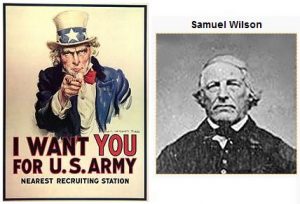

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

The term Uncle Sam was actually the nickname of a man named Samuel Wilson, who was a meat packer from Troy, New York. Sam supplied rations for the soldiers during the War of 1812. He had served in the American Revolution at the age of 15, and while he was born in Massachusetts, he relocated to the town of Troy, New York after the war. In Troy, Samuel and his brother, Ebenezer began the firm of E and S Wilson, a meat packing facility. Samuel was a man of great fairness, reliability, and honesty, who was devoted to his country. All of the local residents really liked Samuel, and they began calling him Uncle Sam.

During the War of 1812, the demand for meat supply for the troops was badly needed. Because he had been a soldier, Samuel had a soft spot in his heart for the soldiers. Secretary of War, William Eustis, made a contract with Elbert Anderson Jr of New York City to supply and issue all rations necessary for the United States forces in New York and New Jersey for one year. Anderson ran an advertisement on October 6, 1813 looking to fill the contract. The Wilson brothers bid for the contract and won. The contract was to fill 2,000 barrels of pork and 3,000 barrels of beef for one year. Their location on the Hudson River, made it ideal to receive the animals and to ship the product. As a security measure, the contractors were required to stamp their name and where the rations came from onto the food they were sending. Wilson’s packages bore the label “E.A. – US,” which stood for Elbert Anderson, the contractor, and the United States. When an individual in the meat packing facility asked what it stood for, a coworker joked and said it referred to Sam Wilson, Uncle Sam. A number of the soldiers were originally from Troy, and familiar with Samuel. When they saw the designation on the barrels, they, being acquainted with Sam Wilson and his nickname Uncle Sam, as well as the knowledge that Wilson was feeding the army, led them to the same conclusion. The local newspaper soon picked up on the story and Uncle Sam eventually gained widespread acceptance as the nickname for the U.S. federal government.

This is, of course, an endearing local story, and therefore, leaves some doubt as to whether it is the actual source of the term. Uncle Sam is mentioned previous to the War of 1812 in the popular song “Yankee Doodle,” which appeared in 1775. Nevertheless, the song doesn’t make it clear whether this reference is to Uncle Sam as a metaphor for the United States, or to an actual person named Sam. Another early reference to the term appeared in 1819, predating Wilson’s contract with the government. The connection between this local saying and the national legend is not easily traced. As early as 1830, there were inquiries into the origin of the term Uncle Sam. The connection between the popular cartoon figure and Samuel Wilson was reported in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1830. Whatever the source, Uncle Sam immediately became popular as a symbol of an ever-changing nation. His “likeness” appeared in drawings in various forms including resemblances to Brother Jonathan, a national personification and emblem of New England, and Abraham Lincoln, and others. In the late 1860s and 1870s, a political cartoonist named Thomas Nast began popularizing the image of Uncle Sam…building on the warm fuzzy feel of a beloved uncle. Nast continued to evolve the image, eventually giving Sam the white beard and stars-and-stripes suit that are associated with the character today.

However, it was a military recruiting poster, created in about 1917, that set the image of Uncle Sam was firmly set into American consciousness. The famous “I Want You” recruiting poster was created by James Montgomery Flagg and four million posters were printed between 1917 and 1918. The image was a really powerful one:  Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

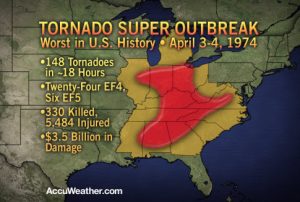

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

The outbreak began when a powerful low pressure system developed on April 1st, across the North American Interior Plains. As it moved into the Mississippi and Ohio Valley areas, a surge of very humid air intensified the storm further, and there were sharp temperature differences between both sides of the system. The National Weather Service began forecasting a severe weather outbreak on April 3, but no one expected the severity of the outbreak that actually occurred. Several F2 and F3 tornadoes struck portions of the Ohio Valley and the South in a separate, earlier outbreak on April 1 and 2, which included three killer tornadoes in Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee. The town of Campbellsburg, northeast of Louisville, was hard-hit in this earlier outbreak, with a large portion of the town destroyed by an F3. Between the two outbreaks, an additional tornado was reported in Indiana in the early morning hours of April 3, several hours before the official start of the outbreak. On Wednesday, April 3, severe weather watches already were issued from the morning from south of the Great Lakes, while in portions of the Upper Midwest, snow was reported, with heavy rain falling  across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

Perhaps the most shocking fact from the 1974 outbreak was the amount of F4 and F5 tornadoes…with an incredible 30 (23 F4s and 7 F5s). The 1974 outbreak featured 30 violent tornadoes in less than one day when the national average is only about 7 per year. All seven of the F5 tornadoes occurred on the 3rd, and Alabama was the state that experienced the highest number of F5 tornadoes that day…three out of seven. The other F5 tornadoes occurred throughout Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. these super outbreaks are some of the most shocking weather phenomena ever.