german

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

Japan entered World War I as a member of the Allies on August 23, 1914. Assisting the Allies with the war effort was not their reason for doing so, however. Once in, Japan seized the opportunity of Imperial Germany’s distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. Because Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, there was minimal fighting as they pushed through to make their territorial gains. Japan was not pressured to enter the war. The Allies had things well in hand, so their motive was obvious. As they swept through, they quickly acquired Germany’s scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the coast of China. While those holdings were relatively easy to overtake, not all of Germany’s holdings were so easy.

In fact, the other Allies quickly started to realize that Japan’s motives weren’t exactly in everyone’s best interests, and they began to push back hard against Japan’s efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Japan’s occupation of Siberia against the Bolsheviks failed, as its wartime diplomacy and limited military action produced few results. Then, by the time of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan was largely frustrated in its ambitions. Nevertheless, Japan had snapped up Germany’s Asian colonies with ease, and even the African colony of Togoland (now Togo and parts of Ghana) fell in less than three weeks. The first real sign of resistance was when German Kamerun (Cameroon) was invaded and lightly contested until 1916. Still, it fell in the end. It seemed that Japan was undefeatable.

Nevertheless, with all the victories, the German colonies in East Africa led by the formidable and undefeated Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck proved to be the exception to the rule. The situation facing von Lettow-Vorbeck and his colonial forces was formidable. Still, von Lettow-Vorbeck knew how to fight, and he refused to back down. When the Japanese came up against von Lettow-Vorbeck, they found themselves heavily outnumbered, and they found themselves with no prospect of reinforcements or much in the way of material support arriving anytime soon.

The fact was that von Lettow-Vorbeck was seeking to tie up British military resources in Africa to relieve some pressure on the European theater. He drew upon his many years of service in Africa to wage a highly effective guerilla war against a much larger enemy. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was probably one of the greatest guerilla warfare strategists of all time…maybe the greatest. Von Lettow-Vorbeck even gained the loyalty of his African soldiers. In those days, it was highly unusual for a commanding officer or any white soldier for that matter, to show any level of respect to the African soldiers. Von Lettow-Vorbeck did, by appointing Black officers and speaking Swahili. The German troops had learned to live off the land and make the most of very little supplies, due to hard lessons drawn from years of colonial warfare in Africa. Those years were filled with atrocities, but they had persevered.

This one small German colonial army tied up the British forces for the duration of the conflict. The British had been plundering food  supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

supplies that devastated the local population. Finally, the German army surrendered on November 25, 1918, in Zambia, two weeks after the November 11, 1918 armistice ended hostilities. Of course, Hitler knew a great officer when he saw one, and so after the war, Hitler immediately offered von Lettow-Vorbek a prestigious position in the Third Reich. In what most would consider a complete shock, von Lettow-Vorbeck bluntly refused the offer, using some very “colorful” language, which shall not be repeated here. It was a courageous, but not very wise move, given the circumstances. Nevertheless, his boldness, as well as his loyalty to the German people, paid off. Von Lettow-Vorbeck was simply too popular with the German people to be eliminated by the regime. He lived to be 94.

Normally, when you think of something like International Students’ Day, most of us think of a day of things like walkouts, protests, and other days during which students are expected to conform to a collective norm of all these issues, like climate change, anti-war protests, and such. No matter what your stance on that is, this is not why International Students’ Day is commemorated. On November 17, 1939, in Czechoslovakia, students the University of Prague were demonstrating against the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Nazi occupation was protested by many groups, and yet, what was a legal protest, was turned into a mass invasion and murder of the student protesters. The event was similar to the Tiananmen Square massacre in which they opened fire on the protesters in China. That one was the Chinese government, while this one was the Nazis. I’s sure the Tiananmen Square massacre was illegal in China, but that was not the case…supposedly anyway, with the Czech protests. Today, the nations have come together in remembering the nine students who were killed, and the others who were sent to concentration camps as a result of their participation in protests over German occupation.

Normally, when you think of something like International Students’ Day, most of us think of a day of things like walkouts, protests, and other days during which students are expected to conform to a collective norm of all these issues, like climate change, anti-war protests, and such. No matter what your stance on that is, this is not why International Students’ Day is commemorated. On November 17, 1939, in Czechoslovakia, students the University of Prague were demonstrating against the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Nazi occupation was protested by many groups, and yet, what was a legal protest, was turned into a mass invasion and murder of the student protesters. The event was similar to the Tiananmen Square massacre in which they opened fire on the protesters in China. That one was the Chinese government, while this one was the Nazis. I’s sure the Tiananmen Square massacre was illegal in China, but that was not the case…supposedly anyway, with the Czech protests. Today, the nations have come together in remembering the nine students who were killed, and the others who were sent to concentration camps as a result of their participation in protests over German occupation.

The world was so shocked by the killings and the taking of captives, but not much could be done. Among the dead were Jan Opletal and worker Václav Sedlácek. The Nazis rounded up the students, murdered nine student leaders and sent over 1,200 students to concentration camps, mainly to Sachsenhausen. As a result of the attacks, all Czech universities and colleges were closed. Technically, by this time Czechoslovakia no longer  existed, as it had been divided into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic under a fascist puppet government. The Nazi authorities were in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Their main target was students of the Medical Faculty of Charles University. That demonstration was held on October 28, and it was to commemorate the anniversary of the independence of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. During this demonstration the student Jan Opletal was shot, and later died from his injuries on November 11th. On November 15th, his body was supposed to be transported from Prague to his home in Moravia. The funeral procession attracted thousands of students, who turned the event into an anti-Nazi demonstration. The Nazis would not allow such a demonstration, so the Nazi authorities took drastic measures in response. They closed all Czech higher education institutions, and arrested the more than 1,200 students, all of whom were then sent to concentration camps. They also executed nine students and professors without trial on November 17th. Historians speculate that the Nazis granted permission for the funeral procession already expecting a violent outcome. Their plan was to use that as a pretext for closing down universities and purging anti-fascist dissidents. I would have to agree. In that way, it was easier to place blame on the students and staff, and not the Nazis.

existed, as it had been divided into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic under a fascist puppet government. The Nazi authorities were in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Their main target was students of the Medical Faculty of Charles University. That demonstration was held on October 28, and it was to commemorate the anniversary of the independence of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. During this demonstration the student Jan Opletal was shot, and later died from his injuries on November 11th. On November 15th, his body was supposed to be transported from Prague to his home in Moravia. The funeral procession attracted thousands of students, who turned the event into an anti-Nazi demonstration. The Nazis would not allow such a demonstration, so the Nazi authorities took drastic measures in response. They closed all Czech higher education institutions, and arrested the more than 1,200 students, all of whom were then sent to concentration camps. They also executed nine students and professors without trial on November 17th. Historians speculate that the Nazis granted permission for the funeral procession already expecting a violent outcome. Their plan was to use that as a pretext for closing down universities and purging anti-fascist dissidents. I would have to agree. In that way, it was easier to place blame on the students and staff, and not the Nazis.

In 2009, on the 70th anniversary of November 17, 1939, OBESSU and ESU promoted a number of initiatives throughout Europe to commemorate the date. An event was held from the 16th to the 18th of November at the University of Brussels, focusing on the history of the students’ movement and its role in promoting active citizenship against authoritarian regimes. The conference gathered around 100 students representing national students and student unions from over 29 European countries, as well as some international delegations. Today, International Students’ Day is a day of remembrance to honor these brave students, who gave their lives and their freedom for a cause the believed in. Some countries, like Czechoslovakia have named it a national holiday.

In 2009, on the 70th anniversary of November 17, 1939, OBESSU and ESU promoted a number of initiatives throughout Europe to commemorate the date. An event was held from the 16th to the 18th of November at the University of Brussels, focusing on the history of the students’ movement and its role in promoting active citizenship against authoritarian regimes. The conference gathered around 100 students representing national students and student unions from over 29 European countries, as well as some international delegations. Today, International Students’ Day is a day of remembrance to honor these brave students, who gave their lives and their freedom for a cause the believed in. Some countries, like Czechoslovakia have named it a national holiday.

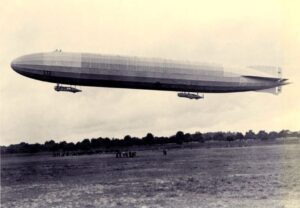

The first power-driven airship was built by a French inventor decades before the Zeppelin was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900. The Zeppelin was a motor-driven rigid airship. The earlier airships were smaller, but Hilter always wanted the most innovative, largest, and deadliest designs of everything, with was likely the reason for the Zeppelin’s size. It was by far the largest airship ever constructed. Hitler didn’t care that size was exchanged for safety. The heavy steel-framed airships were vulnerable to explosion, because they had to be lifted by highly flammable hydrogen gas instead of non-flammable helium gas.

The first power-driven airship was built by a French inventor decades before the Zeppelin was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900. The Zeppelin was a motor-driven rigid airship. The earlier airships were smaller, but Hilter always wanted the most innovative, largest, and deadliest designs of everything, with was likely the reason for the Zeppelin’s size. It was by far the largest airship ever constructed. Hitler didn’t care that size was exchanged for safety. The heavy steel-framed airships were vulnerable to explosion, because they had to be lifted by highly flammable hydrogen gas instead of non-flammable helium gas.

During World War I, the Zeppelins were used as bombers, and the Germans had great success bombing the British Isles with the Zeppelin over the course of 1915 and 1916. The first such  attack on London came on May 31, 1915. That bombing killed 28 people and wounded 60 more. The Germans killed a total of 550 Britons with aerial bombing by May 1916. During one such attack, on September 8, 1915, Heinrich Mathy was the commander of the famed German Zeppelin L13, bombing Aldersgate in central London. His bombs killed 22 people and causing £500,000 worth of damage.

attack on London came on May 31, 1915. That bombing killed 28 people and wounded 60 more. The Germans killed a total of 550 Britons with aerial bombing by May 1916. During one such attack, on September 8, 1915, Heinrich Mathy was the commander of the famed German Zeppelin L13, bombing Aldersgate in central London. His bombs killed 22 people and causing £500,000 worth of damage.

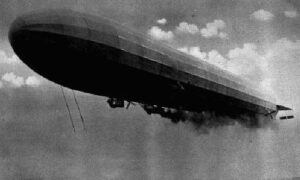

While Mathy was waiting on repairs to his ship, following a bombing run on August 24-25, 1916, he received word that the British had managed for the first time to shoot down a Zeppelin, using incendiary bullets. While he was a fearless pilot, Mathy saw the writing on the wall, and said, “It is only a question of time before we join  the rest. Everyone admits that they feel it. Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not haunted by visions of burning airships, then he would be a braggart.” I’m sure he knew that the Zeppelin was a dangerous ship anyway, especially in a crash, but this new danger made matters much worse. As Mathy had predicted, his Zeppelin L31True to his prediction, Mathy’s L31 was shot down during a raid on London on the night of October 1-2, 1916. He is buried in Staffordshire, in a cemetery constructed by the British for the burial of Germans killed on British soil during both World Wars.

the rest. Everyone admits that they feel it. Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not haunted by visions of burning airships, then he would be a braggart.” I’m sure he knew that the Zeppelin was a dangerous ship anyway, especially in a crash, but this new danger made matters much worse. As Mathy had predicted, his Zeppelin L31True to his prediction, Mathy’s L31 was shot down during a raid on London on the night of October 1-2, 1916. He is buried in Staffordshire, in a cemetery constructed by the British for the burial of Germans killed on British soil during both World Wars.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

The Germans first launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa, on June 22, using over 3 million men. Since the Soviet army was unsuspecting and unprepared, the Germans were very successful in their attack. By July 8th, the Germans had captured more than 280,000 Soviet soldiers and almost 2,600 tanks had been destroyed. With the Germans already a couple of hundred miles inside Soviet territory, Stalin was in a state of panic. He began executing any of his generals who had failed to stop the advancing attack. That was likely a big mistake, because he was basically defeating himself from the inside.

As chief of staff, Halder had been keeping a diary of Hitler’s day-to-day decision-making process. His documentation of Hitler’s processes showed the flaws that Hitler had. I don’t know if that was his plan or if he had wanted to emulate Hitler, but as became emboldened by his successes in Russia, Halder recorded that the “Fuhrer is firmly determined to level Moscow and Leningrad to the ground.” It was Halder’s opinion that Hitler  had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

There were amazing pilots on both sides of World War I. One fighter pilot who really stood out as a superstar was Baron von Richthofen, known to the world as the Red Baron. The Red Baron was born on May 2, 1892, into a family of Prussian nobles. Growing up in the Silesia region of what is now Poland, he lived the kind of life you would expect of a nobleman. He passed the time playing sports, riding horses, and hunting wild game, a passion that would follow him for the rest of his life. As was common and on the wishes of his father, Richthofen was enrolled in military school at age 11. Many people felt that military school would provide the best discipline and training, especially if one were going to be an officer. Shortly before his 18th birthday, he was commissioned as an officer in a German cavalry unit.

Richthofen transferred to the Air Service in 1915, and in 1916 he became one of the first members of fighter squadron Jagdstaffel 2. He was a natural and quickly distinguished himself as a fighter pilot. Then, in 1917 became the leader of Jasta 11. He would go on to lead the larger fighter wing Jagdgeschwader I, which was also known as “The Flying Circus” or “Richthofen’s Circus” mostly because of the bright colors of its aircraft, but maybe because of the way the unit was transferred from one area of Allied air activity to another. When units were moved, it was like a travelling circus. They moved and often set up in tents on improvised airfields.

Between September 1916 and April 1918, he shot down 80 enemy aircraft. That was more than any other pilot during World War I. The Red Baron once wrote, “I never get into an aircraft for fun. I aim first for the head of the pilot, or rather at the head of the observer, if there is one.” He was well known for his crimson-painted Albatros biplanes and Fokker triplanes, and the “Red Baron” by 1918, Richthofen was regarded as a national hero in Germany, and strangely, Richthofen was even respected by his enemies, which is very rare indeed.

Loyal to the end, Richthofen received a fatal wound while flying over Morlancourt Ridge near the Somme River, just after 11:00am on April 21, 1918. He had been pursuing, a Sopwith Camel piloted by Canadian novice Wilfrid Reid “Wop” May of the Number 209 Squadron, Royal Air Force. May had just fired on the Red Baron’s cousin, Lieutenant Wolfram von Richthofen. When he saw his cousin being attacked, the Red Baron flew rescue him. He fired on May’s plane, causing him to pull away, then he chased May across the Somme. The Baron was spotted and briefly attacked by a Camel piloted by May’s school friend and flight commander, Canadian Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown. Brown had to dive steeply at very high speed to intervene, and then had to climb steeply to avoid hitting the ground. Richthofen turned to avoid this attack, and then resumed his pursuit of May.

During this final stage in his pursuit of May, Richthofen was hit by a single .303 bullet through the chest, severely damaging his heart and lungs. He would have bled out in less than a minute. Now pilotless, the plane stalled and went into a steep dive. It hit the ground in a field on a hill near the Bray-Corbie Road, just north of the village of Vaux-sur-Somme. This was in a sector defended by the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The plane bounced heavily when it hit the ground, and the undercarriage collapsed. The fuel tank was smashed before the aircraft skidded to a stop. Several witnesses, including Gunner George Ridgway, reached the crashed plane and found Richthofen already dead, and his face slammed into the butts of his machine guns, breaking his nose, fracturing his jaw and creating contusions on his face.

Number 3 Squadron AFC’s commanding officer Major David Blake, who was responsible for Richthofen’s body, regarded the Red Baron with great respect. It was Blake who was responsible for organizing the funeral, and he decided on a full military funeral. Richthofen’s body was buried in the cemetery at the village of Bertangles, near Amiens, on April 22, 1918. Six of Number 3 Squadron’s officers served as pallbearers, and a guard of honor from the squadron’s other ranks fired a salute. Allied squadrons stationed nearby presented memorial

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

wreaths, one of which was inscribed with the words, “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” It was an extremely respectful way to care for the body of the enemy, and for that, I have much respect for the Number 3 Squadron. Even though this man was the enemy, they knew he was just doing his job, as they would do theirs. It wasn’t personal, it was just war. In 1975 the body was moved to a Richthofen family grave plot at the Südfriedhof in Wiesbaden.

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

When I think of war and of the largest offensive in United States history, I don’t picture a battle in World War I. Nevertheless, I should. The Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was also called the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign, depending on who you were, was a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War I that stretched along the entire Western Front. The offensive ran for a total of 47 days, from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and it was the largest in United States military history, past or present.

The offensive involved 1.2 million American soldiers, and as battles go, it is the second deadliest in American history. During the course of the battle, there were over 350,000 casualties including 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives, and an unknown number of French lives. The losses involving the United States were compounded by the inexperience of many of the troops, the tactics used during the early phases of the operation, and in no small way…the widespread onset of the global influenza outbreak called the “Spanish flu.” The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The pandemic affected an estimated 500 million people, or approximately a third of the global population. It is estimated that 17 to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million people lost their lives, which probably increased the deaths during the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The Meuse–Argonne was the principal engagement of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I, and it was what finally brought the war to an end. It was the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I for the AEF. Nevertheless, by October 31, the Americans had advanced 9.3 miles and had cleared the Argonne Forest. The French advanced 19 miles to the left of the Americans, reaching the Aisne River. The American forces split into two armies at this point. General Liggett led the First Army and advanced to the Carignan-Sedan-Mezieres Railroad. Lieutenant General Robert L Bullard led the Second Army and was directed to move eastward toward Metz. The two United States armies faced portions of 31 German divisions during this phase. The American troops captured German defenses at Buzancy, allowing French troops to cross the Aisne River. There, they rushed forward, capturing Le Chesne, also known as the Battle of Chesne (French: Bataille du Chesne).

In the final days, the French forces conquered the immediate objective, Sedan and its critical railroad hub in a

battle known as the Advance to the Meuse (French: Poussée vers la Meuse), and on November 6, American forces captured surrounding hills. On November 11, news of the German armistice put a sudden end to the fighting. That was fortunate for the armies, but for my 1st cousin twice removed, William Henry Davis, it was six days too late. He lost his life on November 5, 1918, on the west bank of the Meuse during these battles. He was just 30 years old at the time.

During World War II and even earlier really, Adolf Hitler was in the middle of his plan to take over the world. He was ruthless, and when he invaded a country, he didn’t care how many people died, as long as he got his way. The Battle of France took place between May 10, 1940 and June 25, 1940. The surrender of France to the Nazis in 1940 was a complex situation. The German invasion left metropolitan France at the mercy of Nazi armies. Really, once Paris fell on June 14, 1940, the German conquest of France was complete. Part of the problem was that Marshal Henri Petain replaced Paul Reynaud as prime minister and proved to be a weak leader who announced his intention to sign an armistice with the Nazis.

During World War II and even earlier really, Adolf Hitler was in the middle of his plan to take over the world. He was ruthless, and when he invaded a country, he didn’t care how many people died, as long as he got his way. The Battle of France took place between May 10, 1940 and June 25, 1940. The surrender of France to the Nazis in 1940 was a complex situation. The German invasion left metropolitan France at the mercy of Nazi armies. Really, once Paris fell on June 14, 1940, the German conquest of France was complete. Part of the problem was that Marshal Henri Petain replaced Paul Reynaud as prime minister and proved to be a weak leader who announced his intention to sign an armistice with the Nazis.

While not very well known at the time, French General Charles de Gaulle, made a broadcast on June 18, 1940, to France from England, where he would help with the resistance. The Appeal of June 18 was the first speech made by Charles de Gaulle after his arrival in London in 1940 following the Battle of France. The speech was broadcast to Vichy France by the radio services of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). This speech is considered to have marked the beginning of the French Resistance in World War II. It is regarded as one of the most important speeches in French history. General de Gaulle said in his speech, “The leaders who, for many years, were at the head of French armies, have formed a government. This government, alleging our armies to be undone, agreed with the enemy to stop fighting. Of course, we were subdued by the mechanical, ground and air forces of the enemy. Infinitely more than their number, it was the tanks, the airplanes, the tactics of the Germans which made us retreat. It was the tanks, the airplanes, the tactics of the Germans that surprised our leaders to the point to bring them there where they are today.

But has the last word been said? Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? No!

Believe me, I speak to you with full knowledge of the facts and tell you that nothing is lost for France. The same means that overcame us can bring us to a day of victory. For France is not alone! She is not alone! She is not alone! She has a vast Empire behind her. She can align with the British Empire that holds the sea and continues the fight. She can, like England, use without limit the immense industry of United States.

This war is not limited to the unfortunate territory of our country. This war is not finished by the battle of France. This war is a world wide war. All the faults, all the delays, all the suffering, do not prevent there to be, in the world, all the necessary means to one day crush our enemies. Vanquished today by mechanical force, we will be able to overcome in the future by a superior mechanical force.

The destiny of the world is here. I, General de Gaulle, currently in London, invite the officers and the French soldiers who are located in British territory or who would come there, with their weapons or without their weapons, I invite the engineers and the special workers of armament industries who are located in British territory or who would come there, to put themselves in contact with me.

Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished.”

His work with the French Resistance made Charles de Gaulle almost a household word in France. It gave the people hope for freedom. The French Resistance fought to the death to beat the Nazis. This makes me think of current times, and all the freedoms that we have lost. These lessons from the French Resistance are valuable to this day. Never give up. You only lose a battle when you quit fighting. We must never quit fighting.

His work with the French Resistance made Charles de Gaulle almost a household word in France. It gave the people hope for freedom. The French Resistance fought to the death to beat the Nazis. This makes me think of current times, and all the freedoms that we have lost. These lessons from the French Resistance are valuable to this day. Never give up. You only lose a battle when you quit fighting. We must never quit fighting.

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

As you know, war is a tough time to be on a ship. There is no guarantee that the ship will make it through the war, and if a ship goes down in a battle, it usually takes some, if not all of the crew with it. A cat would usually have little chance of survival on a ship that is sinking, but someone forgot to tell Oskar that. Oskar was a black and white patched cat. It is thought that he was originally owned by one of the crewman of the German battleship Bismarck and was on board the ship on May 18, 1941 when the ship set sail on Operation Rheinübung (German for Rhine Exercise). It was the Bismarck’s only mission. On May 27, 1941, the Bismarck was sunk after a fierce sea-battle. The sinking took with it most of the crew. Out of a crew of 2,100 men, only 115 from her crew survived…and one cat. Hours after the sinking, Oscar was found floating on a board and picked from the water by the British destroyer HMS Cossack.

The crew of the Cossack decided that since Oscar was used to being on a ship, he could just stay with them. So, Oscar “served” on board Cossack for the next few months as the ship carried out convoy escort duties in the Mediterranean Sea and north Atlantic Ocean. On October 24, 1941, Cossack was escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to Great Britain when she was severely damaged by a torpedo fired by the German submarine U-563. The surviving crew were transferred to the destroyer HMS Legion, and an attempt was made to tow the badly listing Cossack back to Gibraltar. Unfortunately, the weather was not cooperative, and as it worsened, the task became impossible and had to be abandoned. On October 27, a day after the tow was slipped, Cossack sank to the west of Gibraltar. The initial explosion had blown off one third of the forward section of the ship, killing 159 of the crew, but Oscar survived, and was taken to Gibraltar. To say that a cat has nine lives is almost an understatement when it came to Oscar.

Following the sinking of Cossack, Oscar was given the nickname “Unsinkable Sam” and was soon transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, which by coincidence was instrumental in the destruction of Bismarck, along with Cossack. This assignment was not going to prove safer for Sam, and one might begin to wonder if he should be given another shore assignment…for the sake of the ships. When the Ark Royal was returning from Malta on November 14, 1941, it too was torpedoed, this time by U-81. Again they attempted to tow Ark Royal to Gibraltar, but they were unable to stop the inflow of water, so the attempt was futile. The carrier rolled over and sank 30 miles from Gibraltar. The good news was that due to the slow rate of the sinking, all but one crew member were able to be evacuated, along with, of course, Unsinkable Sam. The survivors, including Sam, who had been found clinging to a floating plank by a Motor Launch and described as “angry but quite unharmed,” were transferred to HMS Lightning and the same HMS Legion which had also rescued the crew of Cossack. Legion would itself be sunk in 1942, and Lightning in 1943. The life of a ship in wartime was not a safe one.

After the third ship sank under Sam’s paws, it was decided that maybe he shouldn’t be on a ship, so he was transferred first to the offices of the Governor of Gibraltar and then sent back to the United Kingdom, where he saw out the remainder of the war living in a seaman’s home in Belfast called the “Home for Sailors.” I think Sam had earned his place there. Sam died in 1955. A pastel portrait of Sam, which was titled “Oscar, the Bismarck’s Cat” by the artist Georgina Shaw-Baker is on display in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Of course, as with all war stories, some authorities question whether Oskar/Sam’s biography might be a “sea story,” because for example, there are pictures of two different cats identified as Oskar/Sam. It is my opinion that whether it is true or not, it lends a lighthearted note to the otherwise tragic stories of war, and therefore, I choose to believe it is true.

Johannes “Macky” Steinhoff was a fighter ace, flying a Luftwaffe fighter plane, during World War II. He was also a German general, and NATO official. Most of the Luftwaffe pilots did not survive to fly operationally throughout the entire World War II period of 1939 to 1945, but Steinhoff managed to do so. One of the highest-scoring pilots with 176 victories, Steinhoff was one of the first to fly the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter in combat as a member of the Jagdverband 44 squadron led by Adolf Galland. Steinhoff received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, and later received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and several foreign awards including the American Legion of Merit and the French Legion of Honour. Steinhoff also played a role in the Fighter Pilots Conspiracy when several senior air force officers confronted Hermann Göring late in the war.

Johannes “Macky” Steinhoff was a fighter ace, flying a Luftwaffe fighter plane, during World War II. He was also a German general, and NATO official. Most of the Luftwaffe pilots did not survive to fly operationally throughout the entire World War II period of 1939 to 1945, but Steinhoff managed to do so. One of the highest-scoring pilots with 176 victories, Steinhoff was one of the first to fly the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter in combat as a member of the Jagdverband 44 squadron led by Adolf Galland. Steinhoff received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, and later received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and several foreign awards including the American Legion of Merit and the French Legion of Honour. Steinhoff also played a role in the Fighter Pilots Conspiracy when several senior air force officers confronted Hermann Göring late in the war.

Steinhoff was born on September 15, 1913 in Bottendorf, Thuringia, the son of an agricultural mill-worker and his traditional housewife. He had two brothers, Bernd and Wolf, and two sisters, Greta and Charlotte. Steinhoff was promoted to Second Lieutenant on 1 April 1936. He married his wife Ursula on April 29, 1939 and they had a son, Wolf and a daughter, Ursula.

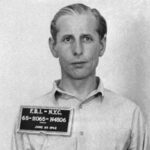

One would think that being one of the first pilots to fly a new airplane would be a huge honor, but flying the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter was risky. It wasn’t necessarily that it crashed any more often than any other plane, but the Messerschmitt Me 262 had a rather huge flaw. The fuel tanks were located in front, under, and behind the pilot. That meant that in a crash situation with fuel on board, the pilot was immediately trapped in an inferno. As a member of Jagdverband-44 (JV-44), flying a Messerschmitt Me 262, Steinhoff was permanently disfigured after receiving major burns across most of his body when he crashed after a failed takeoff. It was such a strange situation. His flight leader’s left wheel had blown out causing him to turn and make a sharp left turn, careening into Steinhoff and causing him to run off the runway, at which point, the fuel tanks ruptured. On that fateful day, Steinhoff and the men he was going up with that day were armed with an experimental under wing rocket which among with the cannon ammunition Steinhoff was carrying. It made escape all the more difficult due to the amount ordnance exploding around him. According to ace fighter pilot and member of JV-44 Franz Stigler, “In a matter of seconds, Steinhoff had turned into a human torch.” Steinhoff was left with horrible scarring for the rest of his life and his chances of survival were slim. Against all odds, he pulled through in the end and retired as a four star general in the new German Air Force at age 59.

After his retirement, he joined the West German government’s Rearmament Office as a consultant on military aviation in 1952 and became one of the principal officials tasked with building the German Air Force during the  Cold War. He became the German Military Representative to the NATO Military Committee in 1960, served as Acting Commander Allied Air Forces Central Europe in NATO 1965–1966, as Inspector of the Air Force 1966–1970 and as Chairman of the NATO Military Committee 1971–1974. In retirement, Steinhoff also became a widely read author of books on German military aviation during the Second World War and the experiences of the German people at that time. On February 21, 1994, Steinhoff died in a Bonn hospital from complications arising from a heart attack he suffered the previous December. He was 80, and had lived in nearby Bad Godesberg.

Cold War. He became the German Military Representative to the NATO Military Committee in 1960, served as Acting Commander Allied Air Forces Central Europe in NATO 1965–1966, as Inspector of the Air Force 1966–1970 and as Chairman of the NATO Military Committee 1971–1974. In retirement, Steinhoff also became a widely read author of books on German military aviation during the Second World War and the experiences of the German people at that time. On February 21, 1994, Steinhoff died in a Bonn hospital from complications arising from a heart attack he suffered the previous December. He was 80, and had lived in nearby Bad Godesberg.

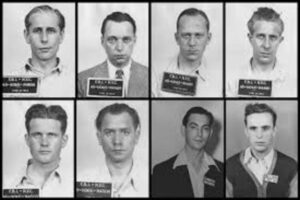

Adolf Hitler was always trying to find a way to infiltrate the nations of the world, because his ultimate goal was to control the world. Most of us would think that he was mostly active in the nations around Germany, and that might be a correct statement, but Hitler also had his sights on the United States. In 1942, Hitler ordered the defense branch of the German Military Intelligence Corps initiated a program to infiltrate the United States and destroy industrial plants, bridges, railroads, waterworks, and Jewish-owned department stores. His ultimate plan was to sabotage all of these, thereby shackling the United States so they would not be an effective enemy in World War II.

Adolf Hitler was always trying to find a way to infiltrate the nations of the world, because his ultimate goal was to control the world. Most of us would think that he was mostly active in the nations around Germany, and that might be a correct statement, but Hitler also had his sights on the United States. In 1942, Hitler ordered the defense branch of the German Military Intelligence Corps initiated a program to infiltrate the United States and destroy industrial plants, bridges, railroads, waterworks, and Jewish-owned department stores. His ultimate plan was to sabotage all of these, thereby shackling the United States so they would not be an effective enemy in World War II.

The Nazis hoped that their sabotage teams would be able to slip into America at the rate of one or two every six weeks…going unnoticed as simple illegal aliens. The first two teams, made up of eight Germans who had all lived in the United States before the war, departed the German submarine base at Lorient, France, in late May. On a heavily foggy June 12, 1942, just before midnight, a German submarine reached the American coast off Amagansett, Long Island. A team was deployed, rowing to the shore in an inflatable boat. Just as the Germans finished burying their explosives in the sand, John C Cullen, a young US Coast Guardsman, came upon them during his regular patrol of the beach. The leader of the team, George Dasch, bribed the suspicious Cullen, and he accepted the money, promising to keep quiet.

At first I found myself feeling angry at the “traitor” John C Cullen, who had sold out his country by accepting a bribe, but then I found out that Cullen was not only not a traitor, but he was a hero and a patriot in every way. As soon as Cullen passed safely back into the fog, he ran two miles back to the Coast Guard station and informed his superiors of his discovery. After retrieving the German supplies from the beach, the Coast Guard called the FBI, which launched a massive manhunt for the saboteurs, who had fled to New York City.

The saboteurs, Dasch and Ernest Burger, were unaware that the FBI was looking for them, but they decided to turn themselves in and betray their colleagues. It might have been because they were afraid they would be captured after the botched landing. On July 15, Dasch called the FBI in New York, but incredibly they failed to take his claims seriously. Dasch decided to travel to FBI headquarters in Washington DC. On July 18, the same day that a second four-man team successfully landed at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, Dasch turned himself in. He agreed to help the FBI capture the rest of the saboteurs.

With Dasch’s help, Burger and the rest of the Long Island team were picked up by July 22, 1942 and by July 27, 1942 the whole of the Florida team was arrested. To preserve wartime secrecy, President Franklin D Roosevelt ordered a special military tribunal consisting of seven generals to try the saboteurs. At the end of July, Dasch was sentenced to 30 years in prison, Burger was sentenced to hard labor for life, and the other six Germans were sentenced to die. The six condemned saboteurs were executed by electric chair in Washington

DC, on August 8, 1942. The situation was handled so quickly, that it is almost shocking to me. Two more German spies were caught after a landing in Maine in 1944. No other instances of German sabotage within wartime America has come to light. We assume that there were no others, but I don’t suppose we will ever know for sure. Nevertheless, no sabotages were ever carried out during that time.

DC, on August 8, 1942. The situation was handled so quickly, that it is almost shocking to me. Two more German spies were caught after a landing in Maine in 1944. No other instances of German sabotage within wartime America has come to light. We assume that there were no others, but I don’t suppose we will ever know for sure. Nevertheless, no sabotages were ever carried out during that time.