german

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the  adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

Some of the saddest pictures taken after the Blitz bombings, were those taken of the children. I can’t imagine what must have been going through their minds as they looked at the devastation that was once their home. They had spent so many wonderful hours playing in their bedrooms, and now they had no bedrooms, or even a house for that matter. Their home had been reduced to a pile of rubble. Sitting there looking at what little is left, some children find a little bit of solace in the fact that a doll or something similar managed to survive the carnage…and they feel somehow blessed. And, of course, they are blessed, because for so many others, there is nothing left.

I’m sure that those little ones looked to their parents, hoping to see a spark of hope, or a little bit of encouragement, but all they saw was a look of shock and disbelief on the  faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

Anticipating the design of the Schienenzeppelin, the earlier Aerowagon, an experimental Russian high-speed railcar, was also equipped with an aircraft engine and a propeller. On 24 July 1921, a group of delegates to the First Congress of the Profintern, led by Fyodor Sergeyev, took the Aerowagon from Moscow to the Tula collieries to test it. Abakovsky was also on board. Although they successfully arrived in Tula on their maiden run, the return route to Moscow was not successful. The Aerowagon derailed at high speed near Serpukhov, killing six of the 22 people on board. A seventh man later died of his injuries.

The Schienenzeppelin railcar was built at the beginning of 1930 in the Hannover-Leinhausen works of the German Imperial Railway Company. The work was completed by Fall of that year. The vehicle was 84 feet 9 3/4 inches long and had just two axles, with a wheelbase of 64 feet 3 5/8  inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

On May 10, 1931, the Schienenzeppelin exceeded a speed of 120 miles per hour for the first time. Afterwards, it toured Germany as an exhibit to the general public throughout Germany. There was still some concern due to the trains speed. On June 21, 1931, it set a new world railway speed record of 143 miles per hour on the Berlin–Hamburg line between Karstädt and Dergenthin, which was not surpassed by any other rail vehicle until 1954. The railcar still holds the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. This high speed was attributable, in addition to other things, to its low weight, which was only 44800 pounds.

While several modifications were attempted, ultimately the Schienenzeppelin was scrapped. Due to many problems with the Schienenzeppelin prototype, the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft decided to go their own way in developing a high-speed railcar, leading to the Fliegender Hamburger (Flying Hamburger) in 1933. This new design was much more suitable for regular service and served also as the basis for later railcar developments. However, many of the Kruckenberg ideas were based on the experiments with Schienenzeppelin and high-speed rail travel, found their way into later DRG railcar designs.

The failure, if it could be called that, of Schienenzeppelin has been attributed to everything from the dangers of  using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

The Dardanelles is a narrow strait running between the Black Sea in the east and the Mediterranean Sea in the west. In World War I it was a much contested area right from the start. It was the subject of a naval attack, spearheaded by Winston Churchill, who was at that time Britain’s young first lord of the Admiralty. On March 18, 1915, six English and four French battleships headed toward the strait. When they reached the area, Turkish mines blasted five of the ships, sinking three of them and forcing the Allied navy to draw back until land troops could be coordinated to begin an invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. With troops from the Ottoman Empire and Germany mounting a spirited defense of the peninsula, however, the Gallipoli offensive turned into a significant setback for the Allies, with 205,000 casualties among British Empire troops and nearly 50,000 among the French.

The Dardanelles is a narrow strait running between the Black Sea in the east and the Mediterranean Sea in the west. In World War I it was a much contested area right from the start. It was the subject of a naval attack, spearheaded by Winston Churchill, who was at that time Britain’s young first lord of the Admiralty. On March 18, 1915, six English and four French battleships headed toward the strait. When they reached the area, Turkish mines blasted five of the ships, sinking three of them and forcing the Allied navy to draw back until land troops could be coordinated to begin an invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. With troops from the Ottoman Empire and Germany mounting a spirited defense of the peninsula, however, the Gallipoli offensive turned into a significant setback for the Allies, with 205,000 casualties among British Empire troops and nearly 50,000 among the French.

When the Allies got involved, the latter offensives in Mesopotamia and Palestine saw more success. By September 1917, the crucial cities of Jerusalem and Baghdad were both in British hands. As the war stretched into the following year, these defeats and an Arab revolt had combined to destroy the Ottoman economy and devastate its land. Some 6 million people were dead and millions more starving. In early October 1918, unable to bank on a German victory any longer, the Turkish government in Constantinople decided to cut its losses and approached the Allies about brokering a peace deal. On October 30, 1918, British and Turkish representatives signed the Treaty of Mudros, which ended Ottoman participation in World War I. According to the terms of the treaty, Turkey had to demobilize its army, release all prisoners of war, and evacuate its Arab provinces, the majority of which were already under Allied control…and open the Dardanelles and Bosporus to Allied warships.

This last condition was fulfilled on November 12, 1918, the day after the armistice, when a squadron of British warships steamed through the Dardanelles, past the ruins of the ancient city of Troy, toward

Constantinople. By the post-war terms worked out by the Allies in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, the waterways that were formerly under Ottoman rule…including the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora and the Bosporus…were now placed under international control, with the designation that their “navigation…shall in future be open, both in peace and war, to every vessel of commerce or of war and to military and commercial aircraft, without distinction of flag.”

Constantinople. By the post-war terms worked out by the Allies in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, the waterways that were formerly under Ottoman rule…including the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora and the Bosporus…were now placed under international control, with the designation that their “navigation…shall in future be open, both in peace and war, to every vessel of commerce or of war and to military and commercial aircraft, without distinction of flag.”

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

A radical pamphlet of mid-July read in part, “We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.” It was in this environment that the Preparedness Parade found itself on July 22, 1916. In spite of that, the 3½ hour long procession of some 51,329 marchers, including 52 bands and 2,134 organizations, comprising military, civic, judicial, state and municipal divisions as well as newspaper, telephone, telegraph and streetcar unions, went ahead as planned. At 2:06pm, about a half hour after the parade began, a bomb concealed in a suitcase exploded on the west side of Steuart Street, just south of Market Street, near the Ferry Building. Ten bystanders were killed by the explosion, and 40 more were wounded, in what became the worst terrorist act in San Francisco history. The city and the nation were outraged, and they declared that justice would be served.

Two radical labor leaders, Thomas Mooney and Warren K Billings, were quickly arrested and tried for the  attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

When we think of disasters at sea, Titanic is the first ship that most likely comes to mind, and while Titanic was a terrible tragedy, it was not the worst disaster at sea, by any means. It is amazing to me, however, that some of the others are never talked about at all, and in fact, you may have never heard about them. Titanic had a capacity of 3547 people, but was only carrying 2223 with passengers and crew. The loss of more than 1500 lives, was horrific to be sure, but it was not the worst disaster at sea in history. That distinction goes to The Wilhelm Gustloff.

When we think of disasters at sea, Titanic is the first ship that most likely comes to mind, and while Titanic was a terrible tragedy, it was not the worst disaster at sea, by any means. It is amazing to me, however, that some of the others are never talked about at all, and in fact, you may have never heard about them. Titanic had a capacity of 3547 people, but was only carrying 2223 with passengers and crew. The loss of more than 1500 lives, was horrific to be sure, but it was not the worst disaster at sea in history. That distinction goes to The Wilhelm Gustloff.

The Wilhelm Gustloff was built by the Blohm & Voss shipyards. It measured 684 feet 1 inch long by 77 feet 5 inches wide with a capacity of 25,484 gross register tons. The ship was launched on 5 May 1937. Originally the ship was intended to be named Adolf Hitler, but was named after Wilhelm Gustloff, a leader of the National Socialist Party’s Swiss branch, who had been assassinated by a Jewish medical student in 1936. Hitler decided on the name change after sitting next to Gustloff’s widow during his memorial service. I guess Hitler managed to do a few nice things in his horrid lifetime. The ship was the first purpose-built cruise liner for the German Labour Front or Deutsche Arbeitsfront,  DAF and used by subsidiary organization Kraft durch Freude, KdF meaning Strength Through Joy. The purpose of the ship was to provide recreational and cultural activities for German functionaries and workers, including concerts, cruises, and other holiday trips, and as a public relations tool, to present “a more acceptable image of the Third Reich.” She was the flagship of the KdF cruise fleet, her last civilian role, until the spring of 1939.

DAF and used by subsidiary organization Kraft durch Freude, KdF meaning Strength Through Joy. The purpose of the ship was to provide recreational and cultural activities for German functionaries and workers, including concerts, cruises, and other holiday trips, and as a public relations tool, to present “a more acceptable image of the Third Reich.” She was the flagship of the KdF cruise fleet, her last civilian role, until the spring of 1939.

The Wilhelm Gustloff became a German hospital ship from September 1939 to November 1940, with its official designation being Lazarettschiff. Then, beginning on 20 November 1940, the medical equipment was removed from the ship and she was repainted from the hospital ship colors of white with a green stripe to standard naval grey. As a consequence of the British blockade of the German coastline, she was used as a barracks ship for approximately 1,000 U-boat trainees of the 2nd Submarine Training Division in the port of Gdynia, which had been occupied by Germany and renamed Gotenhafen. The ship was based near Danzig. Then, as things started to go from bad to worse during World War II, the Germans decided that they needed to evacuate as many people as possible from Courland, East Prussia and Danzig, West Prussia. On  January 30, 1945 during Operation Hannibal, which was the naval evacuation of German troops and civilians from Courland, East Prussia, and Danzig, West Prussia as the Soviet Army advanced. The Wilhelm Gustloff’s final voyage was to evacuate German refugees and military personnel as well as technicians who worked at advanced weapon bases in the Baltic from Gdynia, then known to the Germans as Gotenhafen, to Kiel. The ship’s capacity was 1465, but because they were evacuating people, about 9,400 people were onboard. The ship was hit by a torpedo from Soviet submarine S-13 in the Baltic Sea. It quickly sank, taking all 9,400 people with it. The loss of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst disaster at sea in history.

January 30, 1945 during Operation Hannibal, which was the naval evacuation of German troops and civilians from Courland, East Prussia, and Danzig, West Prussia as the Soviet Army advanced. The Wilhelm Gustloff’s final voyage was to evacuate German refugees and military personnel as well as technicians who worked at advanced weapon bases in the Baltic from Gdynia, then known to the Germans as Gotenhafen, to Kiel. The ship’s capacity was 1465, but because they were evacuating people, about 9,400 people were onboard. The ship was hit by a torpedo from Soviet submarine S-13 in the Baltic Sea. It quickly sank, taking all 9,400 people with it. The loss of the Wilhelm Gustloff remains the worst disaster at sea in history.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In the summer of 1914, the Dresden was patrolling the Caribbean Sea. Its assignment was to safeguard German investments and German citizens living abroad in the region. Then, on July 20, during a bitter civil war in Mexico, the Dresden was called upon to give safe passage to Mexican president, Victoriano Huerta, by transporting him and his family as they escaped to Jamaica, where they received asylum from the British government. Then came news from Europe of Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia and the imminent possibility of war. The German’s put the fleet on alert. By the first week of August the nations of Europe were at war. The Dresden was sent to South America to attack British shipping interests there, and it sunk several merchant ships as it traveled to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. The Dresden eluded the British naval squadron in  the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

Just five weeks later, the Dresden was the only German ship to escape destruction at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on November 8, when the British light cruisers Inflexible and Invincible, commanded by Sir Doveton Sturdee, sank four of von Spee’s ships. Lost were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Nurnberg. As a crew member of Dresden wrote later of watching one of the other ships sink, “Each one of us knew he would never see his comrades again, no one on board the cruiser can have had any illusions about his fate.” Then the Dresden escaped under cover of bad weather south of the Falkland Islands.

Dresden consistently avoided capture by the British navy over the next several months, while sinking a number of cargo ships and then seeking refuge in the network of channels and bays in southern Chile. In need of repairs, the Dresden put into an island off the Chilean coast, in Cumberland Bay on March 8th. Captain, Fritz Emil von Luedecke, had decided the repairs were necessary in the wake of such heavy and extended use. Captain von Luedecke sent out many messages asking for fuel in the hopes of reaching any passing coal ships in the area, but the messages were picked up the British ships, Kent and Glasgow six days later. After a  hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

When we look at the reasons that the United States entered World War II, we think of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and we would be correct, but there was another dictator who committed so many atrocities during and before World War II, that it seems to me inevitable that we would have had to make that decision sooner or later. Adolf Hitler was a German politician, the leader of the Nazi Party, elected Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and Führer, or leader of Nazi Germany from 1934 to 1945. One of his worst acts as Führer of Nazi Germany, was when he initiated World War II in Europe with the invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the worst act was, of course, the Holocaust.

When we look at the reasons that the United States entered World War II, we think of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and we would be correct, but there was another dictator who committed so many atrocities during and before World War II, that it seems to me inevitable that we would have had to make that decision sooner or later. Adolf Hitler was a German politician, the leader of the Nazi Party, elected Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and Führer, or leader of Nazi Germany from 1934 to 1945. One of his worst acts as Führer of Nazi Germany, was when he initiated World War II in Europe with the invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the worst act was, of course, the Holocaust.

During the Holocaust, an insane Hitler, decided that the Jewish people were Untermenschen, or sub-human and socially undesirable, and determined in his heart to kill them. His first move in that direction was to begin rounding them up and placing them in prison camps. And one of the worst was Auschwitz. For a time, Hitler only placed the men in Auschwitz, but then on March 26, 1942, the first women prisoners arrived at Auschwitz.  Of course, Hitler’s intent was always to put the prisoners to death, but he decided to use them in whatever capacity he felt necessary and useful, before the time came to kill them. Since he considered the sub-human, he felt no guilt making them slaves. The prisoners were forced to work long hours, and were also used for medical experimentation. When the prisoners entered the camp, they were strip searched, male and female alike, and forced to stand naked in front of the guards during that time. It didn’t matter how cold they were. They did not count in the eyes of the Germans, because they were Untermenschen…sub-human. As a woman, I can only imagine how these first female prisoners must have felt. They were already very much aware that the Germans did not respect their race, so why would they feel differently about the fact that they were women. It would have been a very scary time. I’m sure they did not know if they would be raped and then killed, or what would happen to them. Their entry into the prison camp had already proven that they were nothing in the eyes of their captors.

Of course, Hitler’s intent was always to put the prisoners to death, but he decided to use them in whatever capacity he felt necessary and useful, before the time came to kill them. Since he considered the sub-human, he felt no guilt making them slaves. The prisoners were forced to work long hours, and were also used for medical experimentation. When the prisoners entered the camp, they were strip searched, male and female alike, and forced to stand naked in front of the guards during that time. It didn’t matter how cold they were. They did not count in the eyes of the Germans, because they were Untermenschen…sub-human. As a woman, I can only imagine how these first female prisoners must have felt. They were already very much aware that the Germans did not respect their race, so why would they feel differently about the fact that they were women. It would have been a very scary time. I’m sure they did not know if they would be raped and then killed, or what would happen to them. Their entry into the prison camp had already proven that they were nothing in the eyes of their captors.

Between 1939 and 1945, there were many plans to try to assassinate Hitler. The most well known, Operation Valkyrie, which came from within Germany and was at least partly driven by the increasing prospect of a German defeat in the war. On July 20, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in one of Hitler’s headquarters…known as the Wolf’s Lair at Rustenburg. Hitler survived because staff officer Heinz Brandt moved the briefcase containing the bomb behind a leg of the heavy conference table. When the bomb exploded, the table deflected much of the blast. Later, Hitler ordered savage reprisals resulting in the execution of more than 4,900 people. In the end, he would take his own life, in an effort not to be taken alive. Not a bad thing if you ask me, because the world is truly well rid of him.

Between 1939 and 1945, there were many plans to try to assassinate Hitler. The most well known, Operation Valkyrie, which came from within Germany and was at least partly driven by the increasing prospect of a German defeat in the war. On July 20, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in one of Hitler’s headquarters…known as the Wolf’s Lair at Rustenburg. Hitler survived because staff officer Heinz Brandt moved the briefcase containing the bomb behind a leg of the heavy conference table. When the bomb exploded, the table deflected much of the blast. Later, Hitler ordered savage reprisals resulting in the execution of more than 4,900 people. In the end, he would take his own life, in an effort not to be taken alive. Not a bad thing if you ask me, because the world is truly well rid of him.

Submarines have been around a long time, but during the world wars, Germany built a submarine that was superior to any other submarine of the time. Called the U-Boat, the name was short for Unterseeboot, or under sea boat. Winston Churchill said, “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Churchill identified the threat that the U-Boats posed. The Atlantic Lifeline was vital to Britain’s survival. If Germany had been able to prevent merchant ships from carrying food, raw materials, troops and their equipment from North America to Britain, the outcome of World War II could have been very different. Britain might have been starved into submission, and her armies would not have been equipped with American built tanks and vehicles. The U-Boats were a serious threat. The Battle of the Atlantic was a must win situation. If Germany won that battle, Britain would likely have lost the war.

Submarines have been around a long time, but during the world wars, Germany built a submarine that was superior to any other submarine of the time. Called the U-Boat, the name was short for Unterseeboot, or under sea boat. Winston Churchill said, “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Churchill identified the threat that the U-Boats posed. The Atlantic Lifeline was vital to Britain’s survival. If Germany had been able to prevent merchant ships from carrying food, raw materials, troops and their equipment from North America to Britain, the outcome of World War II could have been very different. Britain might have been starved into submission, and her armies would not have been equipped with American built tanks and vehicles. The U-Boats were a serious threat. The Battle of the Atlantic was a must win situation. If Germany won that battle, Britain would likely have lost the war.

From 1918 on, Germany was not supposed to have submarines or submarine crews. However, no checks were in place to stop any research into submarines in Germany and it became clear that during the 1930’s, Germany had been investing time and men into submarine research. Their research and subsequent development of the U-Boat made it a submarine that was very difficult to locate and that made it extremely dangerous. They developed the Enigma machine, which was a series of electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines developed and  used in the early to early-mid twentieth century for commercial and military usage. Enigma was invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I. The codes it could provide were difficult to decipher. German military messages enciphered on the Enigma machine were first broken by the Polish Cipher Bureau, in December 1932. This success was a result of efforts by three Polish cryptologists, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rózycki and Henryk Zygalski, working for Polish military intelligence. Rejewski reverse-engineered the device, using theoretical mathematics and material supplied by French military intelligence. Then, the three mathematicians designed mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, including the cryptologic bomb. In 1938, the Germans made the machine more complex, and increased complexity was repeatedly added to the Enigma machines, making decryption more difficult and requiring further equipment and personnel. It was more than the Poles could readily produce.

used in the early to early-mid twentieth century for commercial and military usage. Enigma was invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I. The codes it could provide were difficult to decipher. German military messages enciphered on the Enigma machine were first broken by the Polish Cipher Bureau, in December 1932. This success was a result of efforts by three Polish cryptologists, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rózycki and Henryk Zygalski, working for Polish military intelligence. Rejewski reverse-engineered the device, using theoretical mathematics and material supplied by French military intelligence. Then, the three mathematicians designed mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, including the cryptologic bomb. In 1938, the Germans made the machine more complex, and increased complexity was repeatedly added to the Enigma machines, making decryption more difficult and requiring further equipment and personnel. It was more than the Poles could readily produce.

Finally there was a breakthrough. The astonishing achievements of the codebreakers of Bletchley Park saved countless lives. At their peak, there were 12,000 codebreakers at Bletchley Park, 8,000 of them women. The codebreakers helped bring victory in North Africa by giving British commander General Montgomery details of  Erwin Rommel’s battle plans and providing the routes of the Nazi supply convoys. This allowed the Royal Navy the opportunity to sink them. Prior to the codebreakers, the U-Boats were only sunk after damage or near damage was done to other ships. Such was the case with the first sinking of a U-Boat. German submarine U-39 was a Type IXA U-boat of the Kriegsmarine that operated from 1938 to the first few days of World War II. On 14 September 1939, just 27 days after she began her first patrol, U-39 attempted to sink the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal by firing two torpedoes at her. The torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded just short of the carrier. In retaliation, U-39 was immediately hunted down by three British destroyers. She was disabled with depth charges, and subsequently sunk. All crew members survived and were captured.

Erwin Rommel’s battle plans and providing the routes of the Nazi supply convoys. This allowed the Royal Navy the opportunity to sink them. Prior to the codebreakers, the U-Boats were only sunk after damage or near damage was done to other ships. Such was the case with the first sinking of a U-Boat. German submarine U-39 was a Type IXA U-boat of the Kriegsmarine that operated from 1938 to the first few days of World War II. On 14 September 1939, just 27 days after she began her first patrol, U-39 attempted to sink the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal by firing two torpedoes at her. The torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded just short of the carrier. In retaliation, U-39 was immediately hunted down by three British destroyers. She was disabled with depth charges, and subsequently sunk. All crew members survived and were captured.

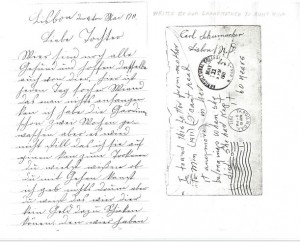

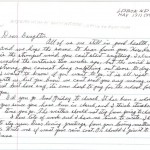

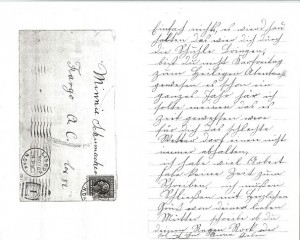

My Uncle Bill Spencer always loved the handwritten letters that were written by his family. It didn’t matter to him if it was nieces or nephews, his siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles or cousins. He saw in every word, great value…as if it were pure gold. The more I look at old letters, and search for information about my family online, the more I realize that Uncle Bill was really on to something. Seeing the handwriting of our ancestors…be it on a letter, draft card, or photograph always gets me excited. To think that my ancestor actually signed that card, or wrote that letter is very cool. I especially love finding things that were written in some other language. When my grandmother Anna Schumacher Spencer and her brother Albert Schumacher were in school, the teacher made fun of their language. When they came home and told their mother, my great grandmother, Henriette Hensel Schumacher, she decided that German would no longer be spoken in their home. I don’t know if she ever changed her mind on that issue, but if German was spoken, it was not often. So to find a letter written in German by my Great Grandmother Henriette Schumacher to her daughter, my Aunt Min Schumacher Spare is especially exciting. I

My Uncle Bill Spencer always loved the handwritten letters that were written by his family. It didn’t matter to him if it was nieces or nephews, his siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles or cousins. He saw in every word, great value…as if it were pure gold. The more I look at old letters, and search for information about my family online, the more I realize that Uncle Bill was really on to something. Seeing the handwriting of our ancestors…be it on a letter, draft card, or photograph always gets me excited. To think that my ancestor actually signed that card, or wrote that letter is very cool. I especially love finding things that were written in some other language. When my grandmother Anna Schumacher Spencer and her brother Albert Schumacher were in school, the teacher made fun of their language. When they came home and told their mother, my great grandmother, Henriette Hensel Schumacher, she decided that German would no longer be spoken in their home. I don’t know if she ever changed her mind on that issue, but if German was spoken, it was not often. So to find a letter written in German by my Great Grandmother Henriette Schumacher to her daughter, my Aunt Min Schumacher Spare is especially exciting. I

wish that I understood then, what I understand now about the handwriting of my ancestors. I am so excited about to find these great letters from people I have come to feel like I know well.

wish that I understood then, what I understand now about the handwriting of my ancestors. I am so excited about to find these great letters from people I have come to feel like I know well.

When I look at the handwriting of my great grandmother, I see a woman who, even in the face of much pain and adversity, prided herself on her handwriting. Of course, life happens, and we can’t always have the same control of our handwriting that we once might have, but at the time of this letter in May of 1911, her handwriting was pretty and delicate. My great grandmother suffered much with Rheumatoid Arthritis, and yet, I believe that she loved beautiful things, and that she was a delicate and beautiful woman. I know that she was so proud of her family. She would like to help them all she could, but with a large family, and tough times, it was not much. Nevertheless, it was her hope that all of her children would succeed in anything they chose to do…after all, America was the land of opportunity.

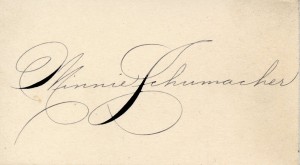

Mina Schumacher always wanted to be a teacher, but in the end, she became a bookkeeper. I think she was probably ok with that, but maybe always felt a bit of regret. Nevertheless, her hanwriting to me shows strong

woman who loved the pretty and delicate things in life. She often signed things using beautiful script or calligraphy. It was her own sense of style. Many people never give any thought to the impression their signature will make on another person, but she did, and I loved it since the first time I saw it in my dad’s photo album. It was just as beautiful and graceful as she was. She knew that the handwriting of our ancestors is important.

woman who loved the pretty and delicate things in life. She often signed things using beautiful script or calligraphy. It was her own sense of style. Many people never give any thought to the impression their signature will make on another person, but she did, and I loved it since the first time I saw it in my dad’s photo album. It was just as beautiful and graceful as she was. She knew that the handwriting of our ancestors is important.

After I wrote the story about the sinking of the Bismarck, my nephew, Steve Spethman told me about a documentary he had about the man who located the Bismarck, and the search for it. Of course, I jumped at the chance to watch it, but when I was done watching it, I felt…different. It’s easy to be excited about a victory in a battle in wartime, or in a war that your dad fought in. It’s easy to set aside the thoughts of lives lost in historic battles, when you know that the battle had to be fought, and the victory would determine the course of the world stage. The problem with that thinking though, is that all too often…especially in countries governed by an evil dictator, such as Adolf Hitler, the people involved in the war, have no choice as to whether or not to fight. I know that a draft is sometimes necessary, but I would much rather have a military machine composed of volunteers than one from a draft. I think volunteers know what they are walking into. It is a cause they agree with, not one they were forced to accept.

After I wrote the story about the sinking of the Bismarck, my nephew, Steve Spethman told me about a documentary he had about the man who located the Bismarck, and the search for it. Of course, I jumped at the chance to watch it, but when I was done watching it, I felt…different. It’s easy to be excited about a victory in a battle in wartime, or in a war that your dad fought in. It’s easy to set aside the thoughts of lives lost in historic battles, when you know that the battle had to be fought, and the victory would determine the course of the world stage. The problem with that thinking though, is that all too often…especially in countries governed by an evil dictator, such as Adolf Hitler, the people involved in the war, have no choice as to whether or not to fight. I know that a draft is sometimes necessary, but I would much rather have a military machine composed of volunteers than one from a draft. I think volunteers know what they are walking into. It is a cause they agree with, not one they were forced to accept.

The movie about the Bismarck’s location, while mostly about the location of a sunken ship, was very different  from the documentaries I had seen about other ships, like the Titanic. While both ships were located by the same man, Robert Ballard, the feelings taken away from the Bismarck, both for Ballard and for the audience were quite different. The addition of commentary from some of the actual survivors of the Bismarck, as well as men on the ships who went in for the final sinking and the rescue of survivors, was very sobering. I was very moved by the German men who remembered the name of the man, Joe Brooks, who risked his own life to try to pull them from the water. They said, in fact, that his name was revered among German soldiers everywhere. This was a man who, in a war situation, chose to do good to his enemies…an almost unheard of act in wartime, but that act from the middle of a war, is still remembered 74 years later.

from the documentaries I had seen about other ships, like the Titanic. While both ships were located by the same man, Robert Ballard, the feelings taken away from the Bismarck, both for Ballard and for the audience were quite different. The addition of commentary from some of the actual survivors of the Bismarck, as well as men on the ships who went in for the final sinking and the rescue of survivors, was very sobering. I was very moved by the German men who remembered the name of the man, Joe Brooks, who risked his own life to try to pull them from the water. They said, in fact, that his name was revered among German soldiers everywhere. This was a man who, in a war situation, chose to do good to his enemies…an almost unheard of act in wartime, but that act from the middle of a war, is still remembered 74 years later.

So seldom, when talking about a war, do you hear about both sides of the war. While you may hear about  their goals and reasons for going to war, you don’t hear about the human factor of each side. I think that was the thing that made me feel so different…almost somber after the movie. One man said that in a sea battle, you usually never see the enemy. He saw men…just briefly as they were running across the deck of the Bismarck. That was it…until they were in the water beside his ship. Then they weren’t soldiers, but real people in dire straits, who were about to lose their lives. In the end, Robert Ballard stood alone at the back of the ship he was on when he found the Bismarck, and I could tell that he felt the same way as I did. The war and the battle had both been a necessary action on the part of the allies, because evil cannot be allowed to prevail, but that simply does not change the fact that these were real lives and real tragic situations.

their goals and reasons for going to war, you don’t hear about the human factor of each side. I think that was the thing that made me feel so different…almost somber after the movie. One man said that in a sea battle, you usually never see the enemy. He saw men…just briefly as they were running across the deck of the Bismarck. That was it…until they were in the water beside his ship. Then they weren’t soldiers, but real people in dire straits, who were about to lose their lives. In the end, Robert Ballard stood alone at the back of the ship he was on when he found the Bismarck, and I could tell that he felt the same way as I did. The war and the battle had both been a necessary action on the part of the allies, because evil cannot be allowed to prevail, but that simply does not change the fact that these were real lives and real tragic situations.