france

On this day, August 21, 1911, an amateur painter decided to paint a painting near Leonardo da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa, only to find out that someone had walked into the Louvre that morning, taken the priceless painting off the wall, hidden it under his clothing, and walked out of the museum. The first thought is, of course, who would be so brazen, but my second thought is how could he have pulled that off? How much clothing would it take to simply “tuck” a 20 inch by 30 inch painting into his clothing. Nevertheless, earlier that day, Vincenzo Perugia had walked into the Louvre, removed the famed painting from the wall, hid it beneath his clothes, and escaped.

On this day, August 21, 1911, an amateur painter decided to paint a painting near Leonardo da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa, only to find out that someone had walked into the Louvre that morning, taken the priceless painting off the wall, hidden it under his clothing, and walked out of the museum. The first thought is, of course, who would be so brazen, but my second thought is how could he have pulled that off? How much clothing would it take to simply “tuck” a 20 inch by 30 inch painting into his clothing. Nevertheless, earlier that day, Vincenzo Perugia had walked into the Louvre, removed the famed painting from the wall, hid it beneath his clothes, and escaped.

The theft, somehow carried out in complete secrecy, left the entire nation of France is shock. There were many theories as to what could have happened to the priceless painting. Strangely, professional thieves were not on the list of suspects, because they would have realized that it would be too dangerous to try to sell the world’s most famous painting. I suppose that a private art collector might have hired a professional to steal it for a secret collection, but that didn’t seem to be the case. One theory, or  rumor really, in Paris was that the Germans had stolen it to humiliate the French. I’m not sure that made any sense before either of the world wars, but I guess tensions between the nations could have been on the rise then.

rumor really, in Paris was that the Germans had stolen it to humiliate the French. I’m not sure that made any sense before either of the world wars, but I guess tensions between the nations could have been on the rise then.

For two years, investigators and detectives searched for the painting without finding any real leads. Then in November 1913, the thief mad his first move…the one that would eventually bring his doom. Italian art dealer Alfredo Geri received a letter from a man calling himself Leonardo. It indicated that the Mona Lisa was in Florence and would be returned for a hefty ransom. Why he waited two years to ask for a ransom is beyond me, other than the fear of getting caught. The meet was set to pay the ransom, and when Perugia attempted to receive the ransom, he was captured. The painting was recovered, unharmed.

In a way, you could say that this was an inside job. Perugia knew his way around, and knew areas where the  Louvre might be vulnerable. Perugia, a former employee of the Louvre, claimed that he had acted out of a patriotic duty to avenge Italy on behalf of Napoleon. That claim was disproven when prior robbery convictions and Perugia’s diary, with a list of art collectors, caused most people to believe that he had acted solely out of greed. Perugia served seven months of a one-year sentence and later served in the Italian army during the First World War. The Mona Lisa is back in the Louvre, where improved security measures are now in place to protect it. I guess that one good thing came of the theft…better security. Of course, that might have come with technological advances anyway.

Louvre might be vulnerable. Perugia, a former employee of the Louvre, claimed that he had acted out of a patriotic duty to avenge Italy on behalf of Napoleon. That claim was disproven when prior robbery convictions and Perugia’s diary, with a list of art collectors, caused most people to believe that he had acted solely out of greed. Perugia served seven months of a one-year sentence and later served in the Italian army during the First World War. The Mona Lisa is back in the Louvre, where improved security measures are now in place to protect it. I guess that one good thing came of the theft…better security. Of course, that might have come with technological advances anyway.

For many years, I thought my Spencer line came from England, but some things didn’t quite add up. When I started seeing DeSpencer and Le DeSpencer, I suspected that we might have immigrated to England from France, which my DNA proved to be correct. I’m more French than English. Nevertheless, for centuries, my Spencer ancestors did live in England, married English people, and so the line blended into more English blood in the current Spencers.

For many years, I thought my Spencer line came from England, but some things didn’t quite add up. When I started seeing DeSpencer and Le DeSpencer, I suspected that we might have immigrated to England from France, which my DNA proved to be correct. I’m more French than English. Nevertheless, for centuries, my Spencer ancestors did live in England, married English people, and so the line blended into more English blood in the current Spencers.

One Hugh le DeSpencer, who was the 1st Baron le DeSpencer, whose connection to me, while most assuredly there, would have to be researched to determine the level of cousinship, or whatever other relationship it is; was an important ally of Simon de Montfort during the reign of Henry III. He served briefly as Justiciar of England in 1260. In the “Middle Ages in England and Scotland the Chief Justiciar was roughly equivalent to a modern Prime Minister of the United Kingdom as the monarch’s chief minister.” Baron le DeSpencer also served as Constable of the Tower of London. “The Constable of the Tower is the most senior appointment at the Tower of London. In the  Middle Ages a constable was the person in charge of a castle when the owner…the king or a nobleman…was not in residence. The Constable of the Tower had a unique importance as the person in charge of the principal fortress defending the capital city of England.”

Middle Ages a constable was the person in charge of a castle when the owner…the king or a nobleman…was not in residence. The Constable of the Tower had a unique importance as the person in charge of the principal fortress defending the capital city of England.”

As chief justiciar of England, Hugh Le DeSpencer, first played an important part in 1258, when he was prominent on the baronial side in the Mad Parliament of Oxford, so called because they apparently argued a lot… and because of a possible misspelling of the word insigne as insane in whatever this says…”Hoc anno fuit illud insane parliamentum apud Oxoniam.” In 1260 the barons chose Le DeSpencer to succeed Hugh Bigod as Justiciar, and in 1263 the king was further compelled to put the Tower of London in his hands. He was the son  of Hugh le DeSpencer I, born in about 1223 and was summoned to Parliament by Simon de Montfort. Hugh was summoned as Lord DeSpencer on December 14, 1264 and was Chief Justiciar of England and a leader of the baronial party, and so might be deemed a baron, although that may not have been completely legal.

of Hugh le DeSpencer I, born in about 1223 and was summoned to Parliament by Simon de Montfort. Hugh was summoned as Lord DeSpencer on December 14, 1264 and was Chief Justiciar of England and a leader of the baronial party, and so might be deemed a baron, although that may not have been completely legal.

He remained allied with Montfort to the end, and was present at the Battle of Lewes. He was killed fighting on de Montfort’s side at the Battle of Evesham in August 4, 1265. He was slain by Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Wigmore. That killing caused a feud to begin between the DeSpencer and the Mortimer families.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

When World War II began, Giraud was a member of the Superior War Council. He strongly disagreed with Charles de Gaulle about the tactics of using armored troops that were planned. Giraud was made the commander of the 7th Army when it was sent to the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. He was able to delay German troops at Breda on May 13th. The badly depleted 7th Army was then merged with the 9th Army. While the troops were trying to block a German attack through the Ardennes, Giraud was at the front with a reconnaissance patrol when he was captured by German troops at Wassigny on May19th. A German court-martial tried Giraud for ordering the execution of two German saboteurs wearing civilian clothes, but he was acquitted and taken to Königstein Castle near Dresden, which was used as a high-security POW prison. He would be held there for two years.

Not one to just sit around, Giraud began carefully planning his escape. He learned German and memorized a map of the area. He painstakingly made a 150 feet rope out of twine, torn bedsheets, and copper wire, which friends had smuggled into the prison for him. Using a simple code embedded in his letters home, he informed his family of his plans to escape. I doubt if they were surprised, as it would not be the first time he escaped his captors. Finally on April 17, 1942, he was ready. Königstein Castle was built on a hilltop, with steep cliff on one side. After shaving off his moustache and covering his head with a Tyrolean hat to disguise himself, Giraud lowered himself down the cliff of the mountain fortress. He discretely travelled to Schandau where he met his Special Operations Executive (SOE) contact, who provided him with a change of clothes, cash, and identity papers. Thus began the series of tactics designed to get Giraud to the Swiss border by train. By now, the border guards had been informed of his escape and were on the alert for him. Giraud walked through the mountains until he was stopped by two Swiss soldiers, who took him to Basel. Eventually, he was able to slip into Vichy France, where he was finally able to make his identity known. He tried unsuccessfully to convince Marshal Pétain that Germany would lose, and that France must resist the German occupation. His views were rejected, but at least the Vichy government refused to return Giraud to the Germans. Returning him would have been a death sentence, because Hitler had ordered Giraud’s assassination upon being caught. Giraud went to North Africa via a British submarine, and joined the French Free Forces under General Charles de Gaulle. He eventually helped to rebuild the French army.

In January 1943, Giraud took part in the Casablanca Conference along with Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D Roosevelt. Later in the same year, Giraud and de Gaulle became co-presidents of the French Committee of National Liberation, but Giraud lost support and retired in frustration in April 1944. After

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

I have been to and inside the Statue of Liberty, and it is a place I’ll never forget. I was a teenager at the time, but I can still vividly picture the inside, as well as the outside. I think the thing that most stuck in my head is that to go up into the statue was a rather tight corridor. The arm was closed when we were there, but we didn’t really know why. For a time, especially after 9-11, no one was allowed to go into the Statue of Liberty at all, for fear of another terrorist attack.

I have been to and inside the Statue of Liberty, and it is a place I’ll never forget. I was a teenager at the time, but I can still vividly picture the inside, as well as the outside. I think the thing that most stuck in my head is that to go up into the statue was a rather tight corridor. The arm was closed when we were there, but we didn’t really know why. For a time, especially after 9-11, no one was allowed to go into the Statue of Liberty at all, for fear of another terrorist attack.

Prior to the 9-11 concerns, the Statue of Liberty was examined by French and American engineers for structural stability in 1982, as part of the planning for its centennial in 1986. Following the examination, it was announced that the statue was in need of considerable restoration. Careful examination had revealed that the right arm  had been improperly attached to the main structure. It was swaying more and more when strong winds blew and there was a significant risk of structural failure. This is information that I’m thankful I didn’t have when I went up into the statue in 1973. I recall being disappointed that we couldn’t go up in the arm then, but apparently they knew of the issues even then. Of further concern, the head had been installed 2 feet off center, and one of the rays was wearing a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. All the problems warranted the repairs done in 1984. She also got a nose job and her arm was shifted slightly to a better position. This information, though not well know, was really bad news, when you think about it. The statue had been standing in this place for 96 years by the time these flaws were discovered. Imagine what could have happened, especially with the arm improperly

had been improperly attached to the main structure. It was swaying more and more when strong winds blew and there was a significant risk of structural failure. This is information that I’m thankful I didn’t have when I went up into the statue in 1973. I recall being disappointed that we couldn’t go up in the arm then, but apparently they knew of the issues even then. Of further concern, the head had been installed 2 feet off center, and one of the rays was wearing a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. All the problems warranted the repairs done in 1984. She also got a nose job and her arm was shifted slightly to a better position. This information, though not well know, was really bad news, when you think about it. The statue had been standing in this place for 96 years by the time these flaws were discovered. Imagine what could have happened, especially with the arm improperly  installed. The armature structure was badly corroded, and about two percent of the exterior plates needed to be replaced. Although problems with the armature had been recognized as early as 1936, when cast iron replacements for some of the bars had been installed, much of the corrosion had been hidden by layers of paint applied over the years. The whole statue was literally a ticking time bomb. Following the repairs, the statue would be much safer and could again be used, but that was not the end of her secrets.

installed. The armature structure was badly corroded, and about two percent of the exterior plates needed to be replaced. Although problems with the armature had been recognized as early as 1936, when cast iron replacements for some of the bars had been installed, much of the corrosion had been hidden by layers of paint applied over the years. The whole statue was literally a ticking time bomb. Following the repairs, the statue would be much safer and could again be used, but that was not the end of her secrets.

Most people think that the Statue of Liberty was a gift from the nation of France, and while it did come from France, it was actually partly a gift from the manufacturer in France (not the French nation). on top of that, Americans had to pay for the pedestal and partly contributed to the cost of the statue itself. Fundraisers were held in Boston and Philadelphia, in order to win the right to have the statue, but in the end, it went to New York. I’m sure many people who helped with the fundraising were very disappointed. This was another secret of the Statue of Liberty that I did not know.

When we think of Paris, the first thing that comes to mind is the Eiffel Tower. If history had been different, those of us alive today would most likely be completely unaware of the historical icon. The Eiffel Tower was built in 1889, and since that time, over 200,000,000 people have visited it, which makes the Eiffel Tower the most visited monument in the world. The Eiffel Tower was erected for the Paris Exposition, and was inaugurated by the Prince of Wales, who went on to become King Edward VII. The tower was the entrance arch to exposition, and was the most visited site during the Exposition. As they were preparing for the Exposition, seven hundred proposals were submitted in a design competition. In the end, it was the radical design of French engineer Alexandre Gustave Eiffel that was unanimously chosen. Eiffel was assisted in the design by two engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nougier, and architect Stephen Sauvestre.

When we think of Paris, the first thing that comes to mind is the Eiffel Tower. If history had been different, those of us alive today would most likely be completely unaware of the historical icon. The Eiffel Tower was built in 1889, and since that time, over 200,000,000 people have visited it, which makes the Eiffel Tower the most visited monument in the world. The Eiffel Tower was erected for the Paris Exposition, and was inaugurated by the Prince of Wales, who went on to become King Edward VII. The tower was the entrance arch to exposition, and was the most visited site during the Exposition. As they were preparing for the Exposition, seven hundred proposals were submitted in a design competition. In the end, it was the radical design of French engineer Alexandre Gustave Eiffel that was unanimously chosen. Eiffel was assisted in the design by two engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nougier, and architect Stephen Sauvestre.

Believe it or not, there was some controversy over the winning design. The Paris city government actually received a petition, signed by about 300 people in a effort to prevent the city government from constructing the tower. Some famous personalities like Guy de Maupassant, Emile Zola, and Charles Garnier also signed the petition. They felt that the Eiffel Tower would be useless and monstrous, and it endangered French art and history. Wow!! Today, they would be stunned at the beauty it posses, especially when it is lit up at night.

Of course, the tower was ultimately built and it was given out for a 20-year lease. When the lease expired in 1909, it was planned to tear down the iconic tower. In the end, it was its antenna that saved the tower, as it was used for telegraphy. The tower also played an important role in capturing the infamous spy Mata Hari

during World War I. Following these events, the tower gained acceptance among the French. As 1910 arrived, the Eiffel Tower became a part of the International Time Service and the French Radio has been using the tower since 1918. The French Television started using the height of the tower from 1957. I don’t really know if most of us knew about all the other uses for the Eiffel Tower, other than the tourist attraction most of us connect with it.

during World War I. Following these events, the tower gained acceptance among the French. As 1910 arrived, the Eiffel Tower became a part of the International Time Service and the French Radio has been using the tower since 1918. The French Television started using the height of the tower from 1957. I don’t really know if most of us knew about all the other uses for the Eiffel Tower, other than the tourist attraction most of us connect with it.

Today this fantastic structure of iron and rivets is iconic symbol of Paris and people from all over the world come to Paris just to marvel at this man-made wonder. The stunning photographs that have been taken from all angles, and the romantic appeal for so many couples of all ages and nationalities have worked together to make the Eiffel Tower famous.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

Trains have changed over the years, partly because of new innovations, and partly out of necessity. In July 1883, TW Worsdell designed the Class Y14 train for both freight and passenger duties. It was a veritable “maid of all work” that was probably considered the greatest train of all time…until the next great came along anyway. These trains were so successful that all the succeeding chief superintendents continued to build new batches down to 1913 with little design change, with the final total being 289 trains. During World War I, 43 of these engines were in service in France and Belgium.

The men who built these trains became so skilled at their work, that on December 10 – 11, 1891, the Great Eastern Railway’s Stratford Works built one of these locomotives and had it “in steam” with a coat of grey primer in 9 hours 47 minutes. That feat remains a world record. The locomotive then went off to run 36,000 miles on Peterborough to London coal  trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

trains before coming back to the works for the final coat of paint. I guess paint was not a necessity, but rather that the train be viewed by many, so as to show the great accomplishment of the builders. The train lasted 40 years and ran a total of 1,127,750 miles…proving the workmanship of the builders.

Because of their light weight the locomotives were given the Route Availability (RA) number 1, indicating that they could work over nearly all routes. Steam engine trains are generally safe, and still used to this day, although not in modern transport situations. Still, they can pose a problem in certain situations. Just like boilers in homes and commercial buildings, too much pressure that is not alleviated presents a huge danger.

On September 25, 1900, at 8:45am, GER Class Y14 0-6-0 locomotive Number 522, just a year old at the time,  stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

stopped at a signal on the Ipswich side of the level crossing awaiting a route to the Felixstowe branch. While waiting, the the boiler suddenly exploded, killing the engineer, John Barnard and his fireman, William MacDonald, both based at Ipswich engine shed. The boiler was thrown 40 yards forwards over the level crossing and landed on the down platform. Apparently the locomotive had a history of boiler problems although in the official report the boiler foreman at Ipswich engine shed was blamed. I’m not sure how that could have been justified, but times were different then. The victims were buried in Ipswich cemetery and both their gravestones have a likeness of a Y14 0-6-0 carved onto them.

As the Allies were planning the massive D-Day assault which was intended to end World War II in Europe, some strange “coincidences” happened that almost threw a monkey wrench into the whole thing. The planned assault on Normandy, France, in 1944, was to include over 5,000 ships, 1,200 planes, and almost 160,000 men. They were set to invade Europe from the British Isles, when something almost put a stop to it…a series of crossword puzzles. Personally, I hate crossword puzzles. They are boring in my mind, so if I were to find a clue in one, it would likely be a miracle.

As the Allies were planning the massive D-Day assault which was intended to end World War II in Europe, some strange “coincidences” happened that almost threw a monkey wrench into the whole thing. The planned assault on Normandy, France, in 1944, was to include over 5,000 ships, 1,200 planes, and almost 160,000 men. They were set to invade Europe from the British Isles, when something almost put a stop to it…a series of crossword puzzles. Personally, I hate crossword puzzles. They are boring in my mind, so if I were to find a clue in one, it would likely be a miracle.

The problem began with the Dieppe Raid on August 19th, 1942. Dieppe is also in Normandy, but further North. In Dieppe, over 6,000 Allied troops, mostly from Canada, attacked at 5 AM. “They had four main goals: (1) to prove that it was possible to capture a slice of Nazi-occupied Europe, (2) to boost Allied morale, (3) to gain intelligence, and (4) to destroy coastal defenses and other sensitive installations.” The mission failed miserably, with the loss of, capture of, or retreat of almost 60% of the invading forces by 3 PM. This couldn’t have been just coincidental, and the Allies wanted to know what had happened. It seemed quite likely that the Germans had been warned of the attack. How could this have happened. Somehow, the suspicion fell on The Daily Telegraph, a British paper still in business today. I’m sure there were a number of newspapers over the years that were used to pass coded messages to the enemy. And I guess it would take a spy’s mind to figure it all out. It had to be discreet, because the paper can’t just give advance warning notice to the enemy, but they did (and still do) have a crossword puzzle section. What better avenue for coded messages. The thing that really triggered suspicion was that two days before the Dieppe invasion, the clue, “French port” was given. And the solution was “Dieppe,” given the following day…the day before the invasion. When I think about the 6,000 men that walked into an ambush because of that one puzzle, I feel furious. This wasn’t a coincidence, this was deliberate, and it was criminal.

The intelligence personnel quickly focused on Leonard Sydney Dawe…the headmaster of Strand School, who was responsible for the crossword puzzle. They were surprised to think it might be him, because he was a veteran of World War I. In addition, nothing linked him to Nazi Germany. In the end, MI5 concluded that it was just that a chilling coincidence, but was it…really? The Strand School for boys in south London, which no longer exists, still stuck out as being somehow involved. It was learned that when the Germans began their bombardment of the city in 1939, Strand was moved to Effingham in Surrey, which was close to where many American and Canadian forces were based.

The French invasion was called Operation Overlord. It was to take place on June 5th, 1944 and involve a series of joint sea and air landings along the Normandy coast. Rather than mass themselves at one spot, however, they were to land at five different areas according to nationality. The Americans were to land at two places. The first was on the left bank of the Douve estuary…codenamed Utah Beach. The second was the stretch which included Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes, Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, and Vierville-sur-Mer…referred to as Omaha. The  British were also given two landing sites – the first along Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer to Ouistreham…Sword Beach, as well as the strip from Arromanches-Les-Bains, Le Hamel, and La Rivière…Gold Beach. As for the Canadians, they were assigned the stretch from Courseulles, Saint-Aubin, and Bernières…Juno Beach. To ensure the quick off-loading of cargo, portable bridges called “Mulberry Harbors” were built. Ships would tow these to France, assemble them at sea, then drive equipment onto the beaches.

British were also given two landing sites – the first along Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer to Ouistreham…Sword Beach, as well as the strip from Arromanches-Les-Bains, Le Hamel, and La Rivière…Gold Beach. As for the Canadians, they were assigned the stretch from Courseulles, Saint-Aubin, and Bernières…Juno Beach. To ensure the quick off-loading of cargo, portable bridges called “Mulberry Harbors” were built. Ships would tow these to France, assemble them at sea, then drive equipment onto the beaches.

The massive size of the invasion, made it almost impossible to keep a complete secret from the Germans, so the plan was to keep them guessing as to exactly when and where the invasion would take place. It was then that the Allies launched Operation Bodyguard…a series of diversions which convinced the Germans that Normandy was simply a distraction, while the main invasion was to take place elsewhere. The Germans bought it, they didn’t want to take any chances. As a result, they stretched their forces thin in a desperate attempt to cover all of their bases. To keep them off balance, absolute secrecy was vital.

Then, in February 1944, one of The Daily Telegraph’s crossword answers was “JUNO.” The following month, it was “GOLD,” and the month after that, it was “SWORD.” Coincidence? MI5 thought so. Then, when the next puzzle included the clue, “One of the US,” they began to wonder. The next day, the answer given was “UTAH.” This was really too much, and MI5 was getting worried. As soon as the May 22nd edition came out, MI5 anxiously grabbed a copy. Scanning the crossword section, they found yet another suspicious clue…“Red Indian on the Missouri River.” And what was the answer given the next day? “OMAHA.” Lets just say, they were getting nervous. Still, it got worse. The May 27th edition had another damning clue…“Big-Wig.” And the answer was? “OVERLORD.” The clincher came on June 1…four days before lift-off. The solution to 15 Down was “NEPTUNE.”

Dawe was arrested at his school to the astonishment of the students and staff. They then banned the paper’s next publication in case “DDAY” appeared in the next crossword. The US Coast Guard manned USS LST-21 unloads British Army tanks and trucks onto a “Rhino” barge during the early hours of the invasion on Gold Beach, 6 June 1944. Dawe was released after the invasion but refused to speak about his ordeal till 1958. He admitted that they did turn him “inside-out,” and had D-Day turned into another Dieppe, he might have been shot. Many people thought it was all just a coincidence…at least till 1984 when Ronald French, a former student at Strand, came forward. As it turns out, Dawe didn’t create crossword puzzles. He instead had students arrange words on a grid, and when he was satisfied, provided clues to solve them by. Then he’d send the finished work to the paper, taking credit for the work. According to French and other former students who later came forward, everyone in Surrey knew the code words. It seems that because they all hung around the Americans and Canadians, the words had leaked out. The French didn’t know what the words meant, only that the servicemen often said them. So when told to work on the crossword puzzles, he included the codes. After his release, Dawes confronted French and accused him of putting the entire country at risk, but how had this  happened. It seems that despite their own secrecy, the MI5 had apparently forgotten to tell the army to keep their mouths shut. It all came about because when the Allies believed that the war was turning in their favor, the Third Washington Conference…also called the Trident Conference…was held in Washington, DC in May 1943. It was there that plans for an Allied invasion of Sicily, France, and the Pacific were discussed. The careless soldiers that spilled the code words almost cost the Allies the victory. D-Day was a battle that cost the Allies many lives, but it could have been much worse, if the secrets had been passed to the enemy in a way that they could have understood them.

happened. It seems that despite their own secrecy, the MI5 had apparently forgotten to tell the army to keep their mouths shut. It all came about because when the Allies believed that the war was turning in their favor, the Third Washington Conference…also called the Trident Conference…was held in Washington, DC in May 1943. It was there that plans for an Allied invasion of Sicily, France, and the Pacific were discussed. The careless soldiers that spilled the code words almost cost the Allies the victory. D-Day was a battle that cost the Allies many lives, but it could have been much worse, if the secrets had been passed to the enemy in a way that they could have understood them.

It seems like these days, the more unique a motorcycle is, the more attention it gets. I don’t think anyone who as seen an unusual motorcycle, can say that they weren’t impressed, amused, or just shocked. You can’t really believe what you are seeing, but it’s hard to look away too. I sometimes wonder how these people came up with such an idea. I guess it takes a great deal of imagination. Some of these designs, are hilarious, and there is seriously no other word for it. People just think of something that is important in their lives, and turn their motorcycle into so version of that thing.

It seems like these days, the more unique a motorcycle is, the more attention it gets. I don’t think anyone who as seen an unusual motorcycle, can say that they weren’t impressed, amused, or just shocked. You can’t really believe what you are seeing, but it’s hard to look away too. I sometimes wonder how these people came up with such an idea. I guess it takes a great deal of imagination. Some of these designs, are hilarious, and there is seriously no other word for it. People just think of something that is important in their lives, and turn their motorcycle into so version of that thing.

While strange bicycles, and even motorcycles, seem like a hilariously funny idea, that might land you on the

ground sometimes, some strange looking motorcycles would seem to me like something a little riskier…especially if you get some speed behind it. Such is the case with the monocycle. I’m not a big fan of motorcycles anyway, so to modify one just to make it a novelty seems an odd idea, indeed. Still, as long as the safety of the motorcycle doesn’t enter into the picture, I guess it’s ok, but some people really got carried away. There were a few monocycles that people rode, and for me, that seems like a dangerous thing to ride. Motorcycles are hard enough upright with two wheels, but to remove one wheel and ride that contraption on the

ground sometimes, some strange looking motorcycles would seem to me like something a little riskier…especially if you get some speed behind it. Such is the case with the monocycle. I’m not a big fan of motorcycles anyway, so to modify one just to make it a novelty seems an odd idea, indeed. Still, as long as the safety of the motorcycle doesn’t enter into the picture, I guess it’s ok, but some people really got carried away. There were a few monocycles that people rode, and for me, that seems like a dangerous thing to ride. Motorcycles are hard enough upright with two wheels, but to remove one wheel and ride that contraption on the

remaining wheel…just crazy!!

remaining wheel…just crazy!!

Nevertheless, that is what Messrs Cislaghi and Goventosa of Italy did, when they built the Motoruota in the 1920s. While it looked so unusual that is was sure to attract attention, it really was a dangerous motorcycle. Apparently the design was popular in Europe, especially France and Italy. They were interesting, to say the least, and I’m sure everyone would want to see it, but you would never get me on one of these contraptions. I value my life much more than that.

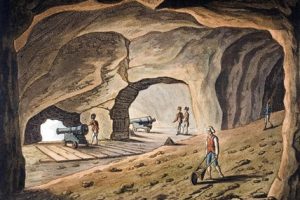

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

The tunnels of Gibraltar were constructed over the course of nearly 200 years, principally by the British Army. Within a land area of only 2.6 square miles, Gibraltar has around 34 miles of tunnels, nearly twice the length of its entire road network. The first tunnels were excavated in the late 18th century. They served as communication passages between artillery positions and housed guns within embrasures cut into the North Face of the Rock, to protect the interior city. More tunnels were constructed in the 19th century to allow easier access to remote areas of Gibraltar and accommodate stores and reservoirs to deliver the water supply of

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

It was to this place that the French Resistance smuggled downed Allied airmen and other escapees from the Nazi regime inside France. Men like Staff Sergeant Arthur Meyerowitz and RAF Bomber Lieutenant R.F.W. Cleaver…two of the men who were smuggled out of occupied France by the French Resistance network known as Réseau Morhange which was created in 1943 by Marcel Taillandier in Toulouse. Taillandier was killed shortly after these two men were smuggled out. He had given his life to protect the airmen he smuggled out as well as to provide intelligence to England. For the airmen who made it to the Rock of Gibraltar, freedom awaited. While

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

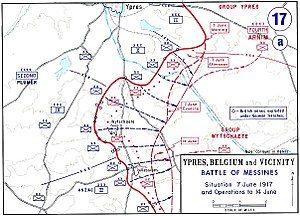

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

On June 7, 1917, they were ready to carry out their secret attack. The explosions created 19 large craters. It would be a crushing victory over the Germans who had no idea of the impending disaster they were about to face. This attack would mark the successful beginning of an Allied offensive designed to break the grinding stalemate on the Western Front in World War I. The time of the attack was set for 3:10am. Precisely on schedule, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The blast from the detonation of all those landmines was heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

Although Messines Ridge battle was, itself was a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect on the German morale. The Germans were forced to retreat to the east, a sacrifice that marked the beginning of their gradual, but continuous loss of territory on the Western Front. It also secured the right flank of the British thrust towards the highly contested Ypres region, which was the eventual objective of the planned offensive. Over the next month and a half, British forces continued to push the Germans back toward the high ridge at Passchendaele, which on July 31 saw the launch of the British offensive known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The Battle of Messines marked the high point of mine warfare. On August 10, 1917, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.

The explosions left a mine crater 40 feet deep. The attack had done its job. Still, after the war was over, the crater remained, and some wanted to change the “feel” of the place. Nowadays, this mine crater is a serene, contemplative place. I’m sure that many who visit there feel the significance of the location, but also know just  how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.