france

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

It is thought, however, that the Doughboys of World War I might have acquired the name in a slightly different way. In fact, there are a variety of theories about the origins of the nickname. One explanation is that the term dates back to the Mexican War of 1846 to 1848, when American infantrymen made long treks over dusty terrain, giving them the appearance of being covered in flour, or dough. As a variation of this account goes, the men were coated in the dust of adobe soil and as a result were called “adobes,” which morphed into “dobies” and, eventually into “doughboys.” Among other theories, according to “War Slang” by Paul Dickson, American journalist and lexicographer H.L. Mencken claimed the nickname could be traced to Continental Army soldiers who kept the piping on their uniforms white through the application of clay. When the troops got rained on the clay on their uniforms turned into “doughy blobs,” supposedly leading to the doughboy moniker.

Whatever the case may be, doughboy was just one of the nicknames given to those who fought in the Great War. For example, “poilu” meaning “hairy one” was a term for a French soldier, as a number of them had beards or mustaches, while a popular slang term for a British soldier was “Tommy,” an abbreviation of Tommy Atkins, a generic name similar to John Doe used in the Unites States on government forms. America’s last

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

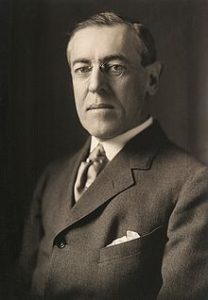

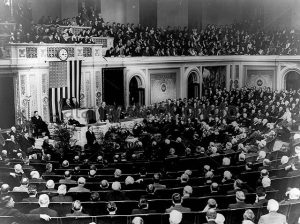

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

The non-stop German offensive continued to take its toll throughout the month of April, however, because the majority of American troops in Europe, who were now arriving at a rate of 120,000 a month, were still not sent into battle. In a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied leaders at Abbeville, near the coast of the English Channel, which began on May 1, 1918, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and General Ferdinand Foch, the recently named Generalissimo of all Allied forces on the Western Front, was trying hard to persuade Pershing to send all the existing American troops to the front at once. Pershing resisted, reminding the group that the United States had entered the war “independently” of the other Allies, and indeed, the United States would insist during and after the war on being known as an “associate” rather than a full-fledged ally. He further stated, “I do not suppose that the American army is to be entirely at the disposal of the French and British commands.” I’m sure his remarks brought with them, much concern.

On May 2, the second day of the meeting, the debate continued, with Pershing holding his ground in the face of  heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

Every time I research one of the weapons used in war, I am more and more stunned by the hatred that brings the need to destroy one another. During World War II, Hitler continuously created…or rather had his scientists create newer, more powerful, and more devastating bombs. His V-1 missile, also known as the V-1 flying bomb, or in German: Vergeltungswaffe 1, meaning “Vengeance Weapon 1” became known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug. In Germany it was known as Kirschkern, or cherrystone, and as Maikäfer or maybug. It was an early cruise missile, and also the first production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power.

Every time I research one of the weapons used in war, I am more and more stunned by the hatred that brings the need to destroy one another. During World War II, Hitler continuously created…or rather had his scientists create newer, more powerful, and more devastating bombs. His V-1 missile, also known as the V-1 flying bomb, or in German: Vergeltungswaffe 1, meaning “Vengeance Weapon 1” became known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug. In Germany it was known as Kirschkern, or cherrystone, and as Maikäfer or maybug. It was an early cruise missile, and also the first production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power.

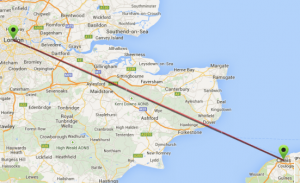

The V-1 was developed at Peenemünde Army Research Center by the Nazi German Luftwaffe during World War II. During initial development it was known by the codename “Cherry Stone.” It was first of the so-called “Vengeance weapons” (V-weapons or Vergeltungswaffen) series designed for terror bombing of London. As one of my readers, Greg (sorry, I don’t know his last name) pointed out to me, it was one of the V weapons…the V-3 to be exact that would ultimately cause the death of Joseph Kennedy, but that is a story for another day. The range of the V-1 missile was limited, and so the thousands of V-1 missiles launched into England were fired from launch facilities along the French (Pas-de-Calais) and Dutch coasts. The first V-1 was launched at London on 13 June 1944, one week after, and actually prompted by the successful Allied landings in Europe. At its peak, more than one hundred V-1s a day were fired at south-east England, 9,521 in total, decreasing in number as sites were overrun until October 1944, when the last V-1 site in range of Britain was overrun by Allied forces. After this, the V-1s were directed at the port of Antwerp and other targets in Belgium, with 2,448 V-1s being launched. The attacks stopped only a month before the war in Europe ended, when the last launch site in the Low Countries was overrun on March 29, 1945.

It took a V-1 about 15 minutes to travel from its launch pad in Calais, France to the heart of London…a distance of nearly 95 miles. Nearly 10,000 V-1s were launched from sites in Northern France over an 80 day period beginning in June 1944. Their targets included London, as well as other cities in southern England. At the peak of the bombing, more than 100 rockets were hitting Britain daily. Casualties climbed to 22,000 people, with more than 6,000 of them fatalities. Hitler hoped his new weapons would crush British morale, bringing

surrender. More V-1s would later be fired from inside Germany itself at Liege and the port of Antwerp. Hitler had underestimated the British, however. The British operated an arrangement of air defenses, including anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft, to intercept the bombs before they reached their targets as part of Operation Crossbow, while the launch sites and underground V-1 storage depots were targets of strategic bombings.

surrender. More V-1s would later be fired from inside Germany itself at Liege and the port of Antwerp. Hitler had underestimated the British, however. The British operated an arrangement of air defenses, including anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft, to intercept the bombs before they reached their targets as part of Operation Crossbow, while the launch sites and underground V-1 storage depots were targets of strategic bombings.

When we think of a series of disasters, it is usually tornadoes, earthquakes, or floods that come to mind. On February 11, 1952, none of the usual suspects were at fault in the series of disasters that began across central Europe. Snow storms don’t normally fall into the category of a series of disasters, but when a storm stalled over middle Europe during the first week of February of 1952, it dumped two feet of snow in parts of France, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. In the vast area of middle Europe, life quickly ground to a standstill. Everything was closed, and travel was impossible. Germany recruited thousands of people and their shovels in an attempt to make the streets passable. In France several people died when their roofs collapsed under the weight of the heavy snow accumulation.

When we think of a series of disasters, it is usually tornadoes, earthquakes, or floods that come to mind. On February 11, 1952, none of the usual suspects were at fault in the series of disasters that began across central Europe. Snow storms don’t normally fall into the category of a series of disasters, but when a storm stalled over middle Europe during the first week of February of 1952, it dumped two feet of snow in parts of France, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. In the vast area of middle Europe, life quickly ground to a standstill. Everything was closed, and travel was impossible. Germany recruited thousands of people and their shovels in an attempt to make the streets passable. In France several people died when their roofs collapsed under the weight of the heavy snow accumulation.

The worst of the storm, however, was felt in Austria, when a series od deadly avalanches took a heavy death toll. It was during the early hours of February 11, 1952, at a ski resort in Melkoede, when a huge mass of the newly fallen snow suddenly crashed down the mountain from above. There was no time to react, and no time to get away. They were trapped. Fifty people were sleeping at the resort. Twenty of them, mostly German tourists were killed, and another ten were seriously injured. In Switzerland and Austria, authorities issued urgent warnings about potential avalanches and some villages were actually evacuated. Nevertheless, all that was not enough. The next day there were more damaging avalanches. In Isenthal, Switzerland, hundreds of cattle and several barns were buried by an avalanche. In Leutasche, Austria, a twelve year old child was saved by people who risked their own lives in the face of a second avalanche that was poised to fall. Seven members of the child’s family were killed by the avalanche.

Avalanches kill more than 150 people worldwide each year. Most are snowmobilers, skiers, and snowboarders, and most deadly avalanches are triggered by the victim or someone in their party. Given that count, I suppose that the 78 people who perished in the February avalanches in middle Europe in 1952, might seem like a small number, but when you consider that these deaths occurred over a period of a few days, and the rest of the deaths by avalanches from that year were not included in that number, the death toll is staggering. This was not the worst avalanche death toll, however. That record, if it is right to call it such, goes to the Huascarán avalanche that was triggered by the 1970 Ancash earthquake in Peru. On 31 May 1970, the Ancash earthquake caused a substantial part of the north side of the mountain to collapse. The avalanche mass, an

estimated 80 million cubic feet of ice, mud and rock, was about half a mile wide and a mile long. It advanced about 11 miles at an average speed of 175 to 200 miles per hour, burying the towns of Yungay and Ranrahirca under ice and rock, killing more than 20,000 people. This avalanche, in my estimation, might have been more of a landslide than an avalanche, and so it’s very possible that all of these people would have died had there been snow or not.

estimated 80 million cubic feet of ice, mud and rock, was about half a mile wide and a mile long. It advanced about 11 miles at an average speed of 175 to 200 miles per hour, burying the towns of Yungay and Ranrahirca under ice and rock, killing more than 20,000 people. This avalanche, in my estimation, might have been more of a landslide than an avalanche, and so it’s very possible that all of these people would have died had there been snow or not.

With everyone arguing about whether or not religion has a place in politics, today seemed a good day to discuss the common misconception people have about the constitutional amendment they so often quote as the basis for their arguments. Our founding fathers came to this country, largely because in England they were forced to attend the Church of England…by law. Whether they agreed or not, or even whether the church was teaching correctly or not, was completely irrelevant. That was the church, and that was where people were expected to go. For any who wonder why so many of us are against the influx of Muslims, this is the reason…not because we disagree with their religion, but because it is the goal of Islam to force the entire world to convert to Islam. Our founding fathers, and indeed most Americans believe so strongly in the right to choose which religion, or even the lack of a religion, we want to practice, that we are willing to fight to keep that right. This amendment is simply not negotiable.

With everyone arguing about whether or not religion has a place in politics, today seemed a good day to discuss the common misconception people have about the constitutional amendment they so often quote as the basis for their arguments. Our founding fathers came to this country, largely because in England they were forced to attend the Church of England…by law. Whether they agreed or not, or even whether the church was teaching correctly or not, was completely irrelevant. That was the church, and that was where people were expected to go. For any who wonder why so many of us are against the influx of Muslims, this is the reason…not because we disagree with their religion, but because it is the goal of Islam to force the entire world to convert to Islam. Our founding fathers, and indeed most Americans believe so strongly in the right to choose which religion, or even the lack of a religion, we want to practice, that we are willing to fight to keep that right. This amendment is simply not negotiable.

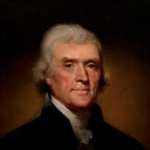

Nevertheless, the misconception comes when people misstate the first amendment, claiming that it means that religion has no place in politics. That statement is fundamentally wrong, and not what Thomas Jefferson had in mind when in 1779, he wrote the “Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.” America was settled by people who wanted religious freedom, and Jefferson believed in freedom of religion, too. He didn’t believe that churches  should be funded by taxes, thereby giving the government authority in the beliefs of the church. The bill said that “no man shall be compelled (forced) to frequent (go to) or support any religious worship, place or ministry whatsoever.” Some people were against it even then, and it did not become law at that time. It did, however, create a friendship between Jefferson and James Madison, who believed the say way.

should be funded by taxes, thereby giving the government authority in the beliefs of the church. The bill said that “no man shall be compelled (forced) to frequent (go to) or support any religious worship, place or ministry whatsoever.” Some people were against it even then, and it did not become law at that time. It did, however, create a friendship between Jefferson and James Madison, who believed the say way.

In 1784, Jefferson left for Paris, France to perform his duties as US foreign minister to France. That left James Madison with the task of making the bill into law. No easy task, because it had failed on its first attempt. Undaunted, Madison presented the bill to the Virginia Assembly, and with a few minor changes, it passed in 1786. Elated, Madison sent word to Jefferson in Paris. When the bill passed, Virginia became the first state to free religions from state rule. It is still part of Virginia’s constitution. It was used as a model for other state’s constitutions. It was also used as a model for the religious language in the Bill of Rights: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” If people would read the Constitutional amendment and the Bill of Rights carefully, they would, indeed find that it says nothing at all about keeping religion out of politics, and everything about keeping the government out of religions. Thomas  Jefferson believed the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom was one of his greatest achievements. So strongly did he believe in his accomplishments, that he wanted his tombstone to list the “things that he had given the people.” It reads: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson Author of the Declaration of Independence of The Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom And Father of the University of Virginia.” Why did Jefferson want the Statute for Religious Freedom on his tombstone? It was because he could see what could happen when one religion was allowed to hold hostage the rest of the nation, or indeed, the world. That is why we will never give up the fight, and we will oppose all religions that would try to force themselves on us. People should stop using this convenient misconception to try to further their own agendas in this nation.

Jefferson believed the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom was one of his greatest achievements. So strongly did he believe in his accomplishments, that he wanted his tombstone to list the “things that he had given the people.” It reads: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson Author of the Declaration of Independence of The Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom And Father of the University of Virginia.” Why did Jefferson want the Statute for Religious Freedom on his tombstone? It was because he could see what could happen when one religion was allowed to hold hostage the rest of the nation, or indeed, the world. That is why we will never give up the fight, and we will oppose all religions that would try to force themselves on us. People should stop using this convenient misconception to try to further their own agendas in this nation.

Anytime a nation’s leader is killed, it’s a disaster, no matter how they died, but it is not so common for the disaster to still be felt when their child is killed, although the nation naturally feels a degree of collective sadness. In a monarchy, however, things are different. The child of the current king stands to be the next leader. These days, having a girl be the next in line for the throne is not a problem, in most nations, but that was not the case in England in 1120. At the time, the king of England was King Henry I. The Norman dynasty had not been in power very long, and the King Henry I was very eager to have the line continue on. His problem was solved with the birth of his only legitimate son, William the Aethling, who was called by the Saxon princely title to stress that his parents had united both Saxon and Norman Royal Houses. William was a warrior prince who, even at the age of seventeen, fought alongside his father to reassert their rights in their Norman lands on the Continent. As was common with kings, especially in that era, and maybe not so unusual in this era, the king had multiple concubines, and so several illegitimate children too. He did have a legitimate daughter named Matilda, but the throne belonged to his son. His illegitimate children were Richard, and oddly, a second Matilda. All seemed right in his world.

Anytime a nation’s leader is killed, it’s a disaster, no matter how they died, but it is not so common for the disaster to still be felt when their child is killed, although the nation naturally feels a degree of collective sadness. In a monarchy, however, things are different. The child of the current king stands to be the next leader. These days, having a girl be the next in line for the throne is not a problem, in most nations, but that was not the case in England in 1120. At the time, the king of England was King Henry I. The Norman dynasty had not been in power very long, and the King Henry I was very eager to have the line continue on. His problem was solved with the birth of his only legitimate son, William the Aethling, who was called by the Saxon princely title to stress that his parents had united both Saxon and Norman Royal Houses. William was a warrior prince who, even at the age of seventeen, fought alongside his father to reassert their rights in their Norman lands on the Continent. As was common with kings, especially in that era, and maybe not so unusual in this era, the king had multiple concubines, and so several illegitimate children too. He did have a legitimate daughter named Matilda, but the throne belonged to his son. His illegitimate children were Richard, and oddly, a second Matilda. All seemed right in his world.

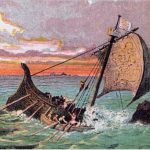

King Henry I was king from August 2, 1100, until his death on December 1, 1135, and expected that his son, Prince William would take his place as king upon his death. Then disaster struck on the November 25, 1120. This was a disaster that would have a dramatic effect, not only on the families of those involved, but on the very fabric of English Government. After a successful battle in 1119, which brought the defeat of King Louis IV of France, and the humiliation at the Battle of Brémule, the King and his entourage were headed home to celebrate. The king was offered a fine ship, the White Ship to travel home in, but he declined because he had already made other arrangements. He suggested that his son and some of the other men could talk the journey on the White Ship.

As the heir to the throne, Prince William attracted the cream of society to surround him. His entourage was to include some three hundred fellow passengers…140 knights and 18 noblewomen, his half-brother, Richard, his half-sister, Matilda the Countess of Perche; his cousins, Stephen and Matilda of Blois, the nephew of the German Emperor Henry V, the young Earl of Chester and most of the heirs to the great estates of England and Normandy. The passengers were all in a mood to celebrate, and asked the Prince for drinks. The prince had brought wine aboard the ship by the barrel-load to help with the festivities. Before long the both passengers and crew became highly intoxicated. Some even left the shop when things started getting abusive.

The people who remained were drunk, and decided that it would be a great idea to try to catch the ship the king was on. The king’s ship had already sailed out into the English Channel.  The people kept pushing the captain to accept the challenge. The captain was sure that his ship could catch the king’s ship, so they set out that evening, and immediately struck a rock in the channel as they left. The ship began to sink, and Prince William was safely in a boat, but he heard his half-sister, Matilda screaming for help. So he left the boat to rescue her. The boat he was in was hit by a group of desparate passengers, and swamped. Prince William was lost and drown. The nation was devastated, and when King Henry I tried to get them to accept his legitimate daughter, Matilda, but they didn’t want to and when the king died, Matilda and her husband found themselves fighting for the throne in a war known as The Anarchy.

The people kept pushing the captain to accept the challenge. The captain was sure that his ship could catch the king’s ship, so they set out that evening, and immediately struck a rock in the channel as they left. The ship began to sink, and Prince William was safely in a boat, but he heard his half-sister, Matilda screaming for help. So he left the boat to rescue her. The boat he was in was hit by a group of desparate passengers, and swamped. Prince William was lost and drown. The nation was devastated, and when King Henry I tried to get them to accept his legitimate daughter, Matilda, but they didn’t want to and when the king died, Matilda and her husband found themselves fighting for the throne in a war known as The Anarchy.

It’s amazing to me that one act of hate can bring so many people to war, but that was what happened with World War I. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip was an ethnic Serb and Yugoslav nationalist from the group Young Bosnia, which was supported by the Black Hand, a nationalist organization in Serbia. The outraged Austrian people and its government threatened mobilization of troops to seek vengeance for their beloved leader and his family.

It’s amazing to me that one act of hate can bring so many people to war, but that was what happened with World War I. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip was an ethnic Serb and Yugoslav nationalist from the group Young Bosnia, which was supported by the Black Hand, a nationalist organization in Serbia. The outraged Austrian people and its government threatened mobilization of troops to seek vengeance for their beloved leader and his family.

The crisis escalated as the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia came to involve Russia, Germany, France, and ultimately Belgium and Great Britain. By mid-August of 1914, the crisis had become a full blown war, with Germany, Austria Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, known as the Central Powers, against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy and Japan, the Allied Powers. The United States would also enter the war as a part of the Allied Powers in 1917. Other factors came into play during the diplomatic crisis that preceded the war, such as misperceptions of intent in that Germany believed that Britain would remain neutral, the belief that war was inevitable, and the speed of the crisis, which was exacerbated by delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications. The four years of the Great War…as it was dubbed…saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction, thanks to grueling trench warfare and the introduction of modern weaponry such as machine guns, tanks and chemical weapons. By the time World War I ended in the defeat of the Central Powers in November 1918, more than 9 million soldiers had been killed and 21 million more wounded.

Evil exists in this world, and it gets worse every day, and assassinations are not new. Chanakya, 350–283 BC, an Indian teacher, philosopher and royal advisor, wrote about assassinations in detail in his political treatise Arthashastra. Later, his student Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire of India, made use of assassinations against some of his enemies, including two of Alexander’s generals Nicanor and Philip. I suppose it should not be a surprise, yet every assassination brings with it shock, fear, and rage.

Countless wars have been fought over one nation’s ruler being killed by someone from another nation. War will be a part of our world until the end of time, but that in no way lessens the worry, fear, and sadness that war always brings. Still, like the Allies of World War I, we cannot let one group or nation hold power over another group or nation…which also explains the need to destroy ISIS.

Countless wars have been fought over one nation’s ruler being killed by someone from another nation. War will be a part of our world until the end of time, but that in no way lessens the worry, fear, and sadness that war always brings. Still, like the Allies of World War I, we cannot let one group or nation hold power over another group or nation…which also explains the need to destroy ISIS.

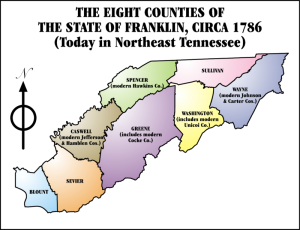

Have you heard of the nation of Frankland…or maybe the nation of Franklin? I hadn’t either, but it was a real place. Early in the history of the United States, its people operated on somewhat limited trust of the government…probably due to the treatment they received in England. In April of 1784, the state of North Carolina ceded its western land claims between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States Congress. The settlers who lived in that area, known as the Cumberland River Valley, had already formed their own government from 1772 to 1777, and their distrust of Congress led the to worry that the area might be sold to Spain or France to pay off war debts owed them by the government. Due to their concerns, North Carolina retracted its cession and started to organize an administration for the territory.

Have you heard of the nation of Frankland…or maybe the nation of Franklin? I hadn’t either, but it was a real place. Early in the history of the United States, its people operated on somewhat limited trust of the government…probably due to the treatment they received in England. In April of 1784, the state of North Carolina ceded its western land claims between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States Congress. The settlers who lived in that area, known as the Cumberland River Valley, had already formed their own government from 1772 to 1777, and their distrust of Congress led the to worry that the area might be sold to Spain or France to pay off war debts owed them by the government. Due to their concerns, North Carolina retracted its cession and started to organize an administration for the territory.

At the same time, representatives from Washington, Sullivan, Spencer (modern-day Hawkins) and Greene  counties declared their independence from North Carolina. Then, in May, they petitioned the United States Congress for statehood as Frankland. The simple majority favored the petition, but Congress could not get the two thirds majority to pass it…not even when the people decided to change the name to Franklin, in the hope of winning favor with Benjamin Franklin and some of the others.

counties declared their independence from North Carolina. Then, in May, they petitioned the United States Congress for statehood as Frankland. The simple majority favored the petition, but Congress could not get the two thirds majority to pass it…not even when the people decided to change the name to Franklin, in the hope of winning favor with Benjamin Franklin and some of the others.

When the petition failed to pass, the people in the area grew angry, and decided to defy Congress. On this day, August 23, 1784, they ceded from the union and functioned as the Free Republic of Franklin (Frankland) for four years. During that time, they had their own constitution, Indian treaties and legislated system of barter in lieu of currency. Two years into the Free Republic of Franklin’s history, North Carolina set up their own parallel government in the area. The economy was weak, and never really gained ground, so the governor, John Sevier approached the Spanish for aid. That move brought a feeling of terror in the government of North Carolina, and they arrested Sevier. The situation worsened when the Cherokee, Chickamauga and Chickasaw began to attack settlements within Franklin’s borders in 1788. Franklin quickly rejoined North Carolina to gain its militia’s protection from attack.

It was a short life for the little nation of Franklin, and eventually they wouldn’t even belong to North Carolina, but rather became a part of the state of Tennessee. It just goes to show that the growing pains of a nation can  take on many forms to reach their destiny as a whole nation. Some changes are good ones, and continue on into the future, and others are not so good, and are sometimes absorbed into the fabric of history and time, and end up looking nothing like the change they started out to be.

take on many forms to reach their destiny as a whole nation. Some changes are good ones, and continue on into the future, and others are not so good, and are sometimes absorbed into the fabric of history and time, and end up looking nothing like the change they started out to be.

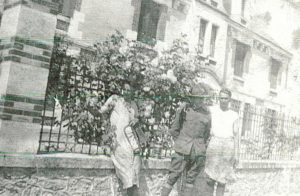

War is never pretty, and yet somehow, I had a picture in my head of the time my grandfather, George Byer spent in World War I that made it seem very benign. I never pictured him being in any danger. You see, my grandfather was a cook in the Army during the war, and somehow I pictured him working in a safe place where the war was a very distant reality, and not something to be faced or dealt with. The cooks in World War I didn’t even get a gun, so they must not be in danger…right? Wrong…very wrong!! The men on the front couldn’t drive home to the safety zone every night after work, like I had pictured in my head. The kitchen was very close to the front. In Grandpa’s case, that kitchen was a commandeered kitchen in the lowest floor of a French castle. As far as anyone knows, the residents of the castle still lived there, although I’m not sure how their meals were handled. Perhaps, their own cooks were allowed a little time in the kitchen, or maybe their meals were served along with the men in the Army. I don’t suppose we will know the full answer to that question in this lifetime.

War is never pretty, and yet somehow, I had a picture in my head of the time my grandfather, George Byer spent in World War I that made it seem very benign. I never pictured him being in any danger. You see, my grandfather was a cook in the Army during the war, and somehow I pictured him working in a safe place where the war was a very distant reality, and not something to be faced or dealt with. The cooks in World War I didn’t even get a gun, so they must not be in danger…right? Wrong…very wrong!! The men on the front couldn’t drive home to the safety zone every night after work, like I had pictured in my head. The kitchen was very close to the front. In Grandpa’s case, that kitchen was a commandeered kitchen in the lowest floor of a French castle. As far as anyone knows, the residents of the castle still lived there, although I’m not sure how their meals were handled. Perhaps, their own cooks were allowed a little time in the kitchen, or maybe their meals were served along with the men in the Army. I don’t suppose we will know the full answer to that question in this lifetime.

For a very long time…until just a few months ago, in fact, I carried the impression in my head that Grandpa’s job was really uneventful, other than the pressure of getting the meals to a large group of hungry men on time. Then, I came across a picture that I had seen several times over the past five years, but this time I was also  looking at the list my aunts had made about what the pictures were about. In that moment, my idea of my grandfather’s service was changed forever. On the list they had written, that the man on the right, or the man in uniform, was Grandpa. The second picture was tagged with, “Castle in France. Owner of castle died in Daddy’s kitchen” and “cooks, who worked under Daddy.” I was instantly intrigued. I spoke to my aunt, Sandy Pattan about it, and found out that indeed, the kitchen was commandeered for the Army’s use, and the owner had been wounded and ran into the kitchen for help. Grandpa tried to save him, but the wounds were too bad, and the owner died right there. The man’s injuries told me that the front was not far from the castle. I suppose you might think I was reaching a little on that thought, but you would be wrong, because as I talked with Aunt Sandy, she told me something else that really clarified the danger my grandfather lived with every day of his time in the service.

looking at the list my aunts had made about what the pictures were about. In that moment, my idea of my grandfather’s service was changed forever. On the list they had written, that the man on the right, or the man in uniform, was Grandpa. The second picture was tagged with, “Castle in France. Owner of castle died in Daddy’s kitchen” and “cooks, who worked under Daddy.” I was instantly intrigued. I spoke to my aunt, Sandy Pattan about it, and found out that indeed, the kitchen was commandeered for the Army’s use, and the owner had been wounded and ran into the kitchen for help. Grandpa tried to save him, but the wounds were too bad, and the owner died right there. The man’s injuries told me that the front was not far from the castle. I suppose you might think I was reaching a little on that thought, but you would be wrong, because as I talked with Aunt Sandy, she told me something else that really clarified the danger my grandfather lived with every day of his time in the service.

It was another day in the castle kitchen, the men were working on the next meal. Suddenly an American soldier ran in and told the cooks to run for the woods. It seemed strange to me that running would be the order they would receive, but remember that Aunt Sandy told me that the cooks had no guns. If they stayed in the castle, they would be sitting ducks, because cooks or not, they were in the American Army, and that made them enemies of the Germans. The reason the men were told to run for the woods…the Germans were coming  and they couldn’t stop them. The soldier didn’t have to tell the cooks twice. They dropped everything and ran. One of the cooks, while running into the woods, stepped on a dead man. The man had been dead a few days, because the cook’s foot went right into the man’s chest. Aunt Sandy told me that the smell was so bad and so permanent that when they couldn’t get the smell out of the man’s clothes, they had to be burned. I had no idea of the things Grandpa saw, nor of the danger he faced. It gave me a whole new picture of Grandpa Byer’s time in World War I. And I came to clearly realize that no job in the service is less dangerous than another…and least not on the front. It’s no wonder that most men don’t want to talk about the war.

and they couldn’t stop them. The soldier didn’t have to tell the cooks twice. They dropped everything and ran. One of the cooks, while running into the woods, stepped on a dead man. The man had been dead a few days, because the cook’s foot went right into the man’s chest. Aunt Sandy told me that the smell was so bad and so permanent that when they couldn’t get the smell out of the man’s clothes, they had to be burned. I had no idea of the things Grandpa saw, nor of the danger he faced. It gave me a whole new picture of Grandpa Byer’s time in World War I. And I came to clearly realize that no job in the service is less dangerous than another…and least not on the front. It’s no wonder that most men don’t want to talk about the war.

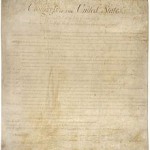

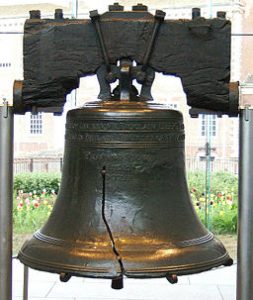

Everyone has heard of the Liberty Bell. The bell was ordered in 1751, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pennsylvania’s original constitution. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly ordered the 2,000 pound copper and tin bell. The bell was placed in the Pennsylvania State House, which is now known as Independence Hall. The bell rang out summoning citizens to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, by Colonel John Nixon. The document was adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress meeting in the State House on July 4th, however, the Liberty Bell, inscribed with the Biblical quotation, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof,” was not rung until the Declaration of Independence was returned from the printer on July 8th.

Everyone has heard of the Liberty Bell. The bell was ordered in 1751, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pennsylvania’s original constitution. The Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly ordered the 2,000 pound copper and tin bell. The bell was placed in the Pennsylvania State House, which is now known as Independence Hall. The bell rang out summoning citizens to the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence, by Colonel John Nixon. The document was adopted by delegates to the Continental Congress meeting in the State House on July 4th, however, the Liberty Bell, inscribed with the Biblical quotation, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof,” was not rung until the Declaration of Independence was returned from the printer on July 8th.

The bell was made of inferior materials, and cracked during the first test. It was recast twice and finally hung from the State House steeple in June 1753. The bell was rung on special occasions, such as when King George III ascended to the throne in 1761, and to call the people together to discuss such important things as the controversial Stamp Act of 1765. With the outbreak of the American Revolution in April 1775, the bell was rung to announce the battles of Lexington and Concord. Of course, the most famous time it was rung was July 8, 1776, when it summoned Philadelphia citizens for the first reading of the Declaration of Independence.

When the British were advancing on Philadelphia in the fall of 1777, the bell was removed and hidden in Allentown to protect it from being melted down by the British to be used for cannons. Following the defeat of the British in 1781, the bell was returned to it’s place in Philadelphia which was the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800. In addition to marking important events, the bell was used as a part of the celebrations such as George Washington’s birthday on February 22, and Independence Day on July 4. In 1839, bell was first given it’s name when it was coined the Liberty Bell in a poem.

As to the crack that finally made the Liberty Bell unsuitable for ringing, there has been some dispute. It was  finally agreed upon that the bell suffered a major break while tolling for the funeral of the chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, in 1835, and in 1846 the crack expanded to its present size while in use to mark Washington’s birthday. After that date, it was decided that the bell was unsuitable for ringing, but it was still ceremoniously tapped on occasion to commemorate important events. On June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded France, the sound of the bell’s dulled ring was broadcast by radio across the United States. In 1976, the Liberty Bell was moved to a new pavilion about 100 yards from Independence Hall in preparation for America’s bicentennial celebrations. The Liberty Bell will always be a symbol of patriotism and liberty in my mind.

finally agreed upon that the bell suffered a major break while tolling for the funeral of the chief justice of the United States, John Marshall, in 1835, and in 1846 the crack expanded to its present size while in use to mark Washington’s birthday. After that date, it was decided that the bell was unsuitable for ringing, but it was still ceremoniously tapped on occasion to commemorate important events. On June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded France, the sound of the bell’s dulled ring was broadcast by radio across the United States. In 1976, the Liberty Bell was moved to a new pavilion about 100 yards from Independence Hall in preparation for America’s bicentennial celebrations. The Liberty Bell will always be a symbol of patriotism and liberty in my mind.