canada

On August 23, 1885, the schooner, Sweepstakes hit a rock near Cove Island on the Canadian side of Lake Huron, and sank in shallow water close to the light station. There she remained until transport could be arranged. Sweepstakes was built in Burlington, Ontario in 1867, by Melancthon Simpson. The wooden schooner’s had two masts, and sported a length 119 feet. The hull’s maximum depth was 20 feet. The schooner weighed approximately 218 tons. Sweepstakes was last owned by George Stewart, who lived in Mooretown, Ontario. Because she ran aground on a rock, her crew were able to escape, so her sinking took with it only one casualty…Sweepstakes, herself. She rests in the Fathom Five National Marine Park.

On August 23, 1885, the schooner, Sweepstakes hit a rock near Cove Island on the Canadian side of Lake Huron, and sank in shallow water close to the light station. There she remained until transport could be arranged. Sweepstakes was built in Burlington, Ontario in 1867, by Melancthon Simpson. The wooden schooner’s had two masts, and sported a length 119 feet. The hull’s maximum depth was 20 feet. The schooner weighed approximately 218 tons. Sweepstakes was last owned by George Stewart, who lived in Mooretown, Ontario. Because she ran aground on a rock, her crew were able to escape, so her sinking took with it only one casualty…Sweepstakes, herself. She rests in the Fathom Five National Marine Park.

On September 3rd the tug Jessie towed Sweepstakes into Big Tub Harbor so she could be repaired, but it was found that the Sweepstakes was beyond repair. So, the repair soon became a salvage of sorts. She was stripped of all useful rigging and equipment. The she sank in her present location in Tub Harbor, at Tobermory, Ontario, Canada. At the time of her sinking, Sweepstakes was still fully loaded with coal. Her cargo was salvaged at a later date. It seems a sad end to the little ship that was majestic in her time, but it isn’t really the end for her.

The area where Sweepstakes now lies is a fairly shallow spot, so she is visible to people on small boats passing  nearby. Her hull is almost completely intact, and she rests in about 20 feet of very clear water at the head of Big Tub Harbor. Two mooring buoys mark her location as a warning to unsuspecting boaters. Although deteriorating a little more each year, the Sweepstakes is one of the best preserved nineteenth-century Great Lakes schooners to be found. Nearby, the wreck of The City Of Grand Rapids rests. Both wrecks are visited frequently by glass-bottom tour boats. During the spring and fall, the site is shared by both divers and boats. Even just looking at pictures of the boats is interesting. It’s almost strange to think you can see a shipwreck from the top of the water.

nearby. Her hull is almost completely intact, and she rests in about 20 feet of very clear water at the head of Big Tub Harbor. Two mooring buoys mark her location as a warning to unsuspecting boaters. Although deteriorating a little more each year, the Sweepstakes is one of the best preserved nineteenth-century Great Lakes schooners to be found. Nearby, the wreck of The City Of Grand Rapids rests. Both wrecks are visited frequently by glass-bottom tour boats. During the spring and fall, the site is shared by both divers and boats. Even just looking at pictures of the boats is interesting. It’s almost strange to think you can see a shipwreck from the top of the water.

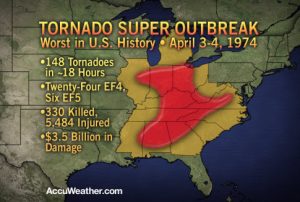

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

We all know that tornadoes are possible just about anywhere in the world…but in the United States, in an area well known as Tornado Alley, tornadoes are a common thing during tornado season, and sometimes outside of tornado season. Tornado Alley gets an average of more than 1,000 tornadoes a year, but on April 3, 1974, a super outbreak began. Over a less than 18 hour span, 148 tornadoes touched down across 13 states, with 21 in Indiana. The tornadoes hit North America from Georgia to Canada within 16 hours. At times there were as many as 15 separate tornadoes on the ground at one time. The Super Outbreak affected a total of 11 US states and Ontario in Canada. The Monticello tornado, which occurred during the weather event, tracked a whopping 121 miles, he longest tornado track in Indiana history! The 1974 tornado outbreak held the record as the largest outbreak in US history, killing 330 people…until the 2011 tornado outbreak, during which 360 tornadoes touched down killing 337 people.

The outbreak began when a powerful low pressure system developed on April 1st, across the North American Interior Plains. As it moved into the Mississippi and Ohio Valley areas, a surge of very humid air intensified the storm further, and there were sharp temperature differences between both sides of the system. The National Weather Service began forecasting a severe weather outbreak on April 3, but no one expected the severity of the outbreak that actually occurred. Several F2 and F3 tornadoes struck portions of the Ohio Valley and the South in a separate, earlier outbreak on April 1 and 2, which included three killer tornadoes in Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee. The town of Campbellsburg, northeast of Louisville, was hard-hit in this earlier outbreak, with a large portion of the town destroyed by an F3. Between the two outbreaks, an additional tornado was reported in Indiana in the early morning hours of April 3, several hours before the official start of the outbreak. On Wednesday, April 3, severe weather watches already were issued from the morning from south of the Great Lakes, while in portions of the Upper Midwest, snow was reported, with heavy rain falling  across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

across central Michigan and much of Ontario, which also had tornadoes.

Perhaps the most shocking fact from the 1974 outbreak was the amount of F4 and F5 tornadoes…with an incredible 30 (23 F4s and 7 F5s). The 1974 outbreak featured 30 violent tornadoes in less than one day when the national average is only about 7 per year. All seven of the F5 tornadoes occurred on the 3rd, and Alabama was the state that experienced the highest number of F5 tornadoes that day…three out of seven. The other F5 tornadoes occurred throughout Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. these super outbreaks are some of the most shocking weather phenomena ever.

There is a tradition in England and a few other nations like Canada and Ireland, that takes place the day after Christmas, called Boxing Day. It is an odd name for a holiday, but I think the purpose of the holiday far outweighs the name of the holiday. People might argue the original purpose of the holiday, but the most straightforward answer as to what it is about would be that, “We are a little greedy here in the England and Ireland in wanting a more extended holiday. It is not enough for us to have only Christmas Day celebrations, we have added to this another event called Boxing Day.” That might be one part of the picture, but the full answer is not that simple. But firstly, it has nothing to do with the sport of boxing.

There is a tradition in England and a few other nations like Canada and Ireland, that takes place the day after Christmas, called Boxing Day. It is an odd name for a holiday, but I think the purpose of the holiday far outweighs the name of the holiday. People might argue the original purpose of the holiday, but the most straightforward answer as to what it is about would be that, “We are a little greedy here in the England and Ireland in wanting a more extended holiday. It is not enough for us to have only Christmas Day celebrations, we have added to this another event called Boxing Day.” That might be one part of the picture, but the full answer is not that simple. But firstly, it has nothing to do with the sport of boxing.

Boxing Day is a national Bank Holiday. It is a day to spend with family and friends and to eat up all the leftovers of Christmas Day, but there is more to it than that. The origins of the day are filled with history and tradition. People have long disputed the origins of the name Boxing Day. The name is actually a reference to holiday gifts. A “Christmas Box” in Britain is a name for a Christmas present. Boxing Day was traditionally a day off for the servants and the day when they received a “Christmas Box” from the master. The servants would also go home on Boxing Day to give “Christmas Boxes” to their families.

Traditionally, a box to collect money for the poor was placed in churches on Christmas day. The boxes were  opened the next day…Boxing Day. The name refers to a nautical tradition. Great sailing ships when setting sail would have a sealed box containing money on board for good luck. Were the voyage a success, the box was given to a priest, opened at Christmas and the contents then given to the poor. Boxing Day is the 26th December is a national holiday in England and Ireland.

opened the next day…Boxing Day. The name refers to a nautical tradition. Great sailing ships when setting sail would have a sealed box containing money on board for good luck. Were the voyage a success, the box was given to a priest, opened at Christmas and the contents then given to the poor. Boxing Day is the 26th December is a national holiday in England and Ireland.

Boxing Day is a time to spend with family or friends, but usually not those seen on Christmas Day itself. In recent times, the day has begun to include many sports. Horse racing is particularly popular with meets all over the country. Many top football teams also play on Boxing Day. Boxing Day is a time when the British show their eccentric side by taking part in all kinds of silly activities. Bizarre traditions include swimming the icy cold English Channel, fun runs, and charity events. Until 2004, Boxing Day hunts were a traditional part of the day, but the ban on fox hunting has put an end to this in its usual sense. Hunters will still gather dressed resplendently in red hunting coats to the sound of the hunting horn. But, since it is now forbidden to chase the fox with dogs, they now follow artificially laid trails.

Another “sport” to emerge in recent years is shopping. Sadly, what was once a day of relaxation and family time sees the start of the sales. Sales used to start in January, post-New Year, but the desire to grab a bargain and for shops to off-load stock means many now begin on Boxing Day. This tradition makes me especially sad, because it is like Black Friday. By moving Black Friday shopping to Thanksgiving, and now post Christmas sales to Boxing Day, have soured many people to shopping on these days, and the whole purpose is defeated.

In Ireland, Boxing Day is also known as “Saint Stephen’s Day” named after the Saint stoned to death for believing in Jesus. In Ireland on Boxing, there was once a barbaric act carried out by the so-called “Wren Boys.” These boys would dress up and go out, and stone wren birds to death then carry their catch around the town knocking on doors and asking for money, the stoning representing what had happened to Saint Stephen. This terrible tradition has now stopped, thank goodness, but the Wrens Boys still dress up. Now, instead they parade around town and collect money for charity. I’m thankful that such a barbaric tradition, has now taken on a new look, and is now used for good.

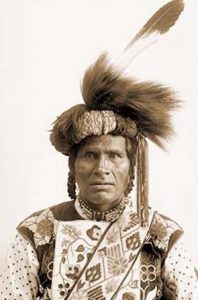

Many people think of the Indians as, well…simply the Indians, whether we intend to or not. I suppose that if we studied the different tribes, their noticeable differences would become very apparent, but if we don’t it’s not so easy to tell them apart. One of the lesser known tribes, at least early on in American history, was the Chippewa tribe. Speculation is that they were already settled in a large village at La Pointe, Wisconsin at about the time that America was discovered. Then, in the early 17th century, they abandoned this area. Many of them returning to their homeland in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, while others settled at the west end of Lake Superior, where they were found by Father Claude Jean Allouez, a Jesuit missionary and French explorer, in 1865.

Many people think of the Indians as, well…simply the Indians, whether we intend to or not. I suppose that if we studied the different tribes, their noticeable differences would become very apparent, but if we don’t it’s not so easy to tell them apart. One of the lesser known tribes, at least early on in American history, was the Chippewa tribe. Speculation is that they were already settled in a large village at La Pointe, Wisconsin at about the time that America was discovered. Then, in the early 17th century, they abandoned this area. Many of them returning to their homeland in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, while others settled at the west end of Lake Superior, where they were found by Father Claude Jean Allouez, a Jesuit missionary and French explorer, in 1865.

The Chippewa, also known as the Ojibway, Ojibwe, and Anishinaabe, are one of the largest and most powerful nations, having nearly 150 different bands located primarily in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and southern Canada…especially Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Ojibway means “to roast till puckered up.” It’s an odd name that referred to the puckered seam on their moccasins. Formerly, the tribe lived along both shores of Lakes Huron and Superior, extending across the Minnesota Turtle Mountains and North Dakota. They were strong in numbers and occupied an large territory, but the Chippewa were never prominent in history, mainly because of their remoteness from the frontier during the period of the colonial wars. They were part of an Algonquian group, including the Ottawa and Potawatomi, which divided when it reached Mackinaw in its westward movement.

Sault Saint Marie was their main headquarters about 1640, as mentioned by Jean Nicolet de Belleborne, a French-Canadian woodsman, who called them Baouichtigouin, meaning “people of the Sault”. In 1642, they  were visited by missionaries Charles Raymbaut and Isaac Jogues, who found them at the Sault and at war with a people to the west, who were probably the Sioux. Because they kept to themselves, away from the frontier, the Chippewa took a very small part in the early colonial wars, but the southern division of the tribe was known to be of warlike disposition. Those to the north of Lake Superior were considered to be peaceful. They were termed by their southern brothers as “the rabbits.” In the north, the members of the tribe were described as the “men of the thick woods” and the “swamp people,” terms used to designate the nature of the country they lived in.

were visited by missionaries Charles Raymbaut and Isaac Jogues, who found them at the Sault and at war with a people to the west, who were probably the Sioux. Because they kept to themselves, away from the frontier, the Chippewa took a very small part in the early colonial wars, but the southern division of the tribe was known to be of warlike disposition. Those to the north of Lake Superior were considered to be peaceful. They were termed by their southern brothers as “the rabbits.” In the north, the members of the tribe were described as the “men of the thick woods” and the “swamp people,” terms used to designate the nature of the country they lived in.

The Chippewa people living south of Lake Superior in the late 1600s were fishermen and hunters. They also grew corn and wild rice. Their possession of wild-rice fields was one of the chief causes of their wars with the Dakota, Fox, and other nations. At about this time, they came into possession of firearms, and began pushing their way westward, in a mixture at peace and war with the Sioux but in almost constant conflict with the Fox tribe. The French, in 1692, reestablished a trading post at Shaugawaumikong, now La Pointe Island, Wisconsin, which became an important Chippewa settlement. In the beginning of the 18th century the Chippewa succeeded in driving the Fox, already reduced by war with the French, from north Wisconsin, compelling them to take refuge with the Sac.

The Chippewa took part with the other tribes of the northwest in all the wars against the frontier settlements to  the close of the war of 1812. Those living within the United States made a treaty with the Government in 1815, and afterwards remained peaceful, residing on reservations or allotted lands within their original territory in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota. By 1900, the Chippewa were estimated to number about 30,000. Today, the collective bands of Chippewa or Ojibwe, are one of the largest groups of Native American People on the North American continent. There are communities in both Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the second largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by the Cree. In the United States, they have the fourth largest population among Native American tribes, surpassed only by the Navajo, Cherokee and Lakota Sioux.

the close of the war of 1812. Those living within the United States made a treaty with the Government in 1815, and afterwards remained peaceful, residing on reservations or allotted lands within their original territory in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and North Dakota. By 1900, the Chippewa were estimated to number about 30,000. Today, the collective bands of Chippewa or Ojibwe, are one of the largest groups of Native American People on the North American continent. There are communities in both Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the second largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by the Cree. In the United States, they have the fourth largest population among Native American tribes, surpassed only by the Navajo, Cherokee and Lakota Sioux.

Part of the War of 1812 involved a border dispute between the United States and British North America, which is present-day Canada. During the war, the Americans launched several invasions into Upper Canada, at the point of present-day Ontario. One section of the border where this was easiest, because of communications and locally available supplies, was along the Niagara River. Fort Erie was the British post at the head of the river, near its source in Lake Erie. In 1812, two American attempts to capture Fort Erie were bungled by Brigadier General Alexander Smyth. Bad weather or poor administration halted the American efforts to cross the river, and Fort Erie remained in British hands.

Part of the War of 1812 involved a border dispute between the United States and British North America, which is present-day Canada. During the war, the Americans launched several invasions into Upper Canada, at the point of present-day Ontario. One section of the border where this was easiest, because of communications and locally available supplies, was along the Niagara River. Fort Erie was the British post at the head of the river, near its source in Lake Erie. In 1812, two American attempts to capture Fort Erie were bungled by Brigadier General Alexander Smyth. Bad weather or poor administration halted the American efforts to cross the river, and Fort Erie remained in British hands.

In 1813, the Americans won the Battle of Fort George at the northern end of the Niagara River. At this point, the British abandoned the Niagara frontier and allowed Fort Erie to fall into American hands without a fight. Unfortunately, the Americans failed to follow up their victory, and later in the year they withdrew most of their soldiers from the Niagara to furnish an ill-fated attack on Montreal. This allowed the British to recover their prior positions and to mount raids which led to the Capture of Fort Niagara and the devastation of large parts of the American side of the Niagara River.

For 1814, a new invasion of Upper Canada was planned under the command of Major General Jacob Brown. Originally aimed at Kingston on Lake Ontario, it was switched to the Niagara because British ships controlled Lake Ontario for the first six months of 1814. The United States finally captured Fort Erie in 1814. It was thought that the British, while outnumbered, surrendered Fort Erie prematurely…at least in the view of the British commanders. They fully expected the outnumbered British troops to stand and fight…to the death, if need be. Because American troops were already concentrated at Buffalo and Black Rock, the attack was to be launched across the southern part of the Niagara frontier. Fort Erie was the first objective that stood in the way, and so, its capture was required. Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond, the British commander in Upper Canada, hoped that the garrison at Fort Erie could at least buy him enough time against the American invasion to concentrate his forces. Major Thomas Buck was given command of the fort with a garrison of 137 British soldiers.

Brown’s force crossed into Canada on July 3, 1814. Brigadier General Winfield Scott landed a mile and a half north of the fort with a brigade of regulars while it was still dark. Another brigade under Eleazar Wheelock Ripley crossed the head of the river to the south of the fort, a little behind schedule due to fog. Meanwhile, New York militia demonstrated opposite Chippewa to distract the British troops in the area. As Scott’s and Ripley’s forces approached Fort Erie, Buck fired only a few shots at the Americans from the fort’s cannon and then surrendered. The Americans had captured an important fort at little cost. The fort’s garrison had bought the British very little time and Buck was later court martialed for his hasty surrender.

From their new base at Fort Erie, Brown next marched up the Niagara River and met the British at the Battle of Chippewa. The British commander at Chippewa, Major General Phineas Riall, believed that the garrison of Fort Erie was still holding out, which contributed to his decision to launch a hasty and ill-fated attack. Following the Battle of Lundy’s Lane in July, British forces under the command of Gordon Drummond advanced and unsuccessfully attempted to besiege the fort. After that it remained in American hands until the American commanders decided to abandon the fort, which was evacuated and blown up in November 1814. These days, with so many historic forts across the nation, it was shocking to me to read that they had blown up the fort,

but I guess they weren’t interested in the historic side of things…they were making history. The fort, which had been built by the British in 1764, was restored, and was incorporated as a village in 1857. It became a town when it merged with Bridgeburg in 1932. Fort Erie is now the site of a large horse-racing track and has steel, aircraft, automotive, paint, and pharmaceutical industries. It is a town with a population of 29,960 in 2011.

but I guess they weren’t interested in the historic side of things…they were making history. The fort, which had been built by the British in 1764, was restored, and was incorporated as a village in 1857. It became a town when it merged with Bridgeburg in 1932. Fort Erie is now the site of a large horse-racing track and has steel, aircraft, automotive, paint, and pharmaceutical industries. It is a town with a population of 29,960 in 2011.

When a body of water stands between two places that people need to go, there are a few options to solve the dilemma…a bridge, a road around, or as was the case of a way across the Detroit River, a tunnel. With a river, you can’t really go around, so often it’s a bridge, but in this case there was a great deal of opposition to a bridge over the river. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Detroiters and Windsorians had been trying to find a way to move people and goods back and forth across the Detroit River. For decades, railroad interests proposed tunnels and bridges galore, but powerful advocates of marine shipping always managed to block those projects, because they did not want to lose business to faster and more capacious trains. Plans for bridges were particularly troubling to those shippers, since just one low-hanging bridge had the potential to keep high-masted sailing vessels off the river altogether.

When a body of water stands between two places that people need to go, there are a few options to solve the dilemma…a bridge, a road around, or as was the case of a way across the Detroit River, a tunnel. With a river, you can’t really go around, so often it’s a bridge, but in this case there was a great deal of opposition to a bridge over the river. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Detroiters and Windsorians had been trying to find a way to move people and goods back and forth across the Detroit River. For decades, railroad interests proposed tunnels and bridges galore, but powerful advocates of marine shipping always managed to block those projects, because they did not want to lose business to faster and more capacious trains. Plans for bridges were particularly troubling to those shippers, since just one low-hanging bridge had the potential to keep high-masted sailing vessels off the river altogether.

In 1871, the region’s railroads finally won permission to build a trans-national tunnel, and workers began to dig into the river at the foot of Detroit’s San Antoine Street. They were forced to abandon the project just 135 feet  under the river, however, when they struck a pocket of sulfurous gas that made workers so ill that none could be persuaded to return. Likewise, in 1879, another tunnel had to be abandoned when it ran right into some unexpectedly difficult to excavate limestone under the river. The first successful Michigan to Canada tunnel project finally opened in 1891. It was the 6,000 foot long Grand Trunk Railway Tunnel at Port Huron.

under the river, however, when they struck a pocket of sulfurous gas that made workers so ill that none could be persuaded to return. Likewise, in 1879, another tunnel had to be abandoned when it ran right into some unexpectedly difficult to excavate limestone under the river. The first successful Michigan to Canada tunnel project finally opened in 1891. It was the 6,000 foot long Grand Trunk Railway Tunnel at Port Huron.

Soon enough, it was clear to most people on both sides of the border that they needed to build some sort of structure for transporting automobiles across the river too. In June 1919, the mayors of Detroit and Windsor decided to build a city to city tunnel that would serve as a memorial to the American and Canadian soldiers who had died in World War I. Even after advocates of the under-construction Ambassador Bridge tried to frighten away the tunnel’s backers by spreading rumors about the danger of subterranean carbon monoxide poisoning, the tunnel boosters were undeterred. One said, they were “inspired by God to have this tunnel built.” Construction began in 1928. First, barges were used to dredge a 2,454 foot long trench across the river. Then workers sank nine 8,000 ton steel and concrete tubes into the trench and welded them together. Finally, an  elaborate ventilation system was built to make sure that the air in the tunnel safe to breathe.

elaborate ventilation system was built to make sure that the air in the tunnel safe to breathe.

On Nov 1, 1930, President Herbert Hoover turned a telegraphic Golden Key in the White House to mark the opening of the 5,160 foot long Detroit-Windsor Tunnel between the United States city of Detroit, Michigan, and the Canadian city of Windsor, Ontario. The tunnel opened to regular traffic on November 3, 1930. The first passenger car it carried was a 1929 Studebaker. In the first nine weeks it was open, nearly 200,000 cars passed through the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel. Today, about 9 million vehicles use the tunnel each year.

After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, on October 4, 1957, inspiring the United States to keep up, or fall behind in the Cold War, the United States launched it’s first satellite on January 31, 1958. That satellite was called Explorer 1, and followed the first two Soviet satellites the previous year…Sputnik 1 and 2. It was the beginning the Cold War Space Race between the two nations. Explorer 1 had mercury batteries that powered the high-power transmitter for 31 days and the low-power transmitter for 105 days. Explorer 1 stopped transmission of data on May 23, 1958 when its batteries died, but remained in orbit for more than 12 years. It reentered the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1970 after more than 58,000 orbits. The Explorer 1 payload consisted of the Iowa Cosmic Ray Instrument. It was without a tape data recorder, which was not modified in time to make it onto the spacecraft. The real-time data received on the ground was therefore very sparse and puzzling showing normal counting rates and no counts at all. I’m not sure what the counting was all about, so I guess I’m more confused than the scientists were. The later Explorer 3 mission, which included a tape data recorder in the payload, provided the additional data for confirmation of the earlier Explorer 1 data.

After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, on October 4, 1957, inspiring the United States to keep up, or fall behind in the Cold War, the United States launched it’s first satellite on January 31, 1958. That satellite was called Explorer 1, and followed the first two Soviet satellites the previous year…Sputnik 1 and 2. It was the beginning the Cold War Space Race between the two nations. Explorer 1 had mercury batteries that powered the high-power transmitter for 31 days and the low-power transmitter for 105 days. Explorer 1 stopped transmission of data on May 23, 1958 when its batteries died, but remained in orbit for more than 12 years. It reentered the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1970 after more than 58,000 orbits. The Explorer 1 payload consisted of the Iowa Cosmic Ray Instrument. It was without a tape data recorder, which was not modified in time to make it onto the spacecraft. The real-time data received on the ground was therefore very sparse and puzzling showing normal counting rates and no counts at all. I’m not sure what the counting was all about, so I guess I’m more confused than the scientists were. The later Explorer 3 mission, which included a tape data recorder in the payload, provided the additional data for confirmation of the earlier Explorer 1 data.

Landsat 1, which was originally named “Earth Resources Technology Satellite 1”, was the first satellite in the United States’ Landsat program. It was the first satellite that was launched with the sole purpose of studying and monitoring the planet. Landsat 1 was a modified version of the Nimbus 4 meteorological satellite and was launched on July 23, 1972 by a Delta 900 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Its orbit was near-polar and it served as a stabilized, Earth-oriented platform for obtaining information on agricultural and forestry resources, geology and mineral resources, hydrology and water resources, geography, cartography, environmental pollution, oceanography and marine resources, and meteorological phenomena. The spacecraft was placed in a sun-synchronous orbit, with an altitude between 564 and 569 miles. The spacecraft was placed in an orbit with an inclination of 99 degrees which orbited the Earth every 103 minutes. The project was renamed to Landsat in 1975.

Landsat 1 had two sensors to achieve its primary objectives…the return beam Vidicon (RBV) and the multispectral scanner (MSS). The RBV was manufactured by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). The RBV obtained visible light and near infrared photographic images of Earth. It was considered the primary sensor. The MSS sensor manufactured by Hughes Aircraft Company was considered an experimental and secondary sensor, until scientists reviewed the data that was beamed back to Earth. After the data was reviewed, the MSS  was considered the primary sensor. The MSS was a four-channel scanner that obtained radiometric images of Earth. From launch until 1974, Landsat 1 transmitted over 100,000 images, which covered more than 75% of the Earth’s surface. The RBV only took 1690 images. In 1976, Landsat 1 discovered a tiny uninhabited island 12 miles off the eastern coast of Canada. This island was named Landsat Island after the satellite. The MSS provided more than 300,000 images over the lifespan of the satellite. NASA oversaw 300 researchers that evaluated the data that Landsat 1 transmitted back to Earth. The Landsat 1 satellite sent data back to earth from its orbit until January of 1978 when its tape recorders malfunctioned. After that, it was taken out of service.

was considered the primary sensor. The MSS was a four-channel scanner that obtained radiometric images of Earth. From launch until 1974, Landsat 1 transmitted over 100,000 images, which covered more than 75% of the Earth’s surface. The RBV only took 1690 images. In 1976, Landsat 1 discovered a tiny uninhabited island 12 miles off the eastern coast of Canada. This island was named Landsat Island after the satellite. The MSS provided more than 300,000 images over the lifespan of the satellite. NASA oversaw 300 researchers that evaluated the data that Landsat 1 transmitted back to Earth. The Landsat 1 satellite sent data back to earth from its orbit until January of 1978 when its tape recorders malfunctioned. After that, it was taken out of service.

My brother-in-law, Chris Hadlock has always loved the outdoors. In fact, for years, he my sister, Allyn and their family have gone camping during his birthday week. They usually go to Red Lodge, Montana, but this year he and Allyn did something a little different. This year, they went to Canada to spend the week in a houseboat, along with my sister, Caryl Reed and her husband, Mike; and my sister, Alena Stevens and her husband Mike. I know they are going to have a great time, and I can’t wait to see pictures of their trip. It’s such a unique kind of a trip, and I know they are all going to have a really great week. It will be a trip to remember, that’s for sure.

My brother-in-law, Chris Hadlock has always loved the outdoors. In fact, for years, he my sister, Allyn and their family have gone camping during his birthday week. They usually go to Red Lodge, Montana, but this year he and Allyn did something a little different. This year, they went to Canada to spend the week in a houseboat, along with my sister, Caryl Reed and her husband, Mike; and my sister, Alena Stevens and her husband Mike. I know they are going to have a great time, and I can’t wait to see pictures of their trip. It’s such a unique kind of a trip, and I know they are all going to have a really great week. It will be a trip to remember, that’s for sure.

This year seems to be shaping up to be one of change for Chris. He retired from the Casper Police Department on June 30th, after 27 years in law enforcement. During those yeas, he served the people of Casper and Natrona County capably and honorably. It has been a strange things for all of us to know that Chris is no longer a police officer. I also think that his retirement is a great loss to the Casper Police Department. Chris worked in so many areas of the department. He was a patrol officer for a number of years, then a supervisor and training officer. Later he hired new officers, and finally he was the supervisor of the detectives. His ability to do any job and do it well, is what made him such an asset to the department. Nevertheless, careers must come to an end sometime, and this was Chris’ time. I know that his new job will be a good career move too, and I am happy for him. Police work is stressful, and it’s time for him to de-stress.

Chris is rocking the career of grandpa too these days. He has three grandchildren so far, and they love to hang out with their grandpa. One of the things they really like to do is to listen to Chris play the guitar. He has been playing for most of his life, and I know his own kids loved to sit and listen to him play too. Now the next generation of kids are learning to love music from him as well. His youngest grandchild, Adelaide loves to help her grandpa play the guitar, and I’m sure the others did too. It is just so wonderful to be a grandparent. You aren’t the disciplinarian, and there is no pressure to be that. You just get to be to person they want to be with as

much as they can. They want to spend the night, and do the things you are doing, even if it’s work! If their grandparents are doing something, it must be the coolest thing in the world. There is just something about being a grandparent. It’s such an honor to watch the next generation of the sweet family you started, expanding to include these new little babies. That’s how Chris and Allyn are feeling now, and how they will feel far into the future. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

much as they can. They want to spend the night, and do the things you are doing, even if it’s work! If their grandparents are doing something, it must be the coolest thing in the world. There is just something about being a grandparent. It’s such an honor to watch the next generation of the sweet family you started, expanding to include these new little babies. That’s how Chris and Allyn are feeling now, and how they will feel far into the future. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

Then, while returning from a trip to the East, Kellogg happened to be on the same train as George Custer and his wife, Elizabeth. Custer was on his way to Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, where he was going to lead the 7th Cavalry in a planned assault on several bands of Indians who had refused to be confined to reservations. There journey was delayed by an unusually heavy winter storm. The train became snowbound. Being the expert that he was, Kellogg improvised a crude telegraph key, connected it to the wires running alongside the track, and sent a message ahead to the fort asking for help. Custer’s brother, Tom, arrived soon after with a sleigh to rescue them. Custer had enjoyed being made famous by the nation’s newspapers during the Civil War, and now, as he prepared for what he hoped would be his greatest victory ever, Custer wanted to make sure his glorious deeds would be adequately covered in the press. Initially, Custer had planned to take his old friend Clement Lounsberry, who was Kellogg’s employer at the Tribune, with him into the field with the 7th Cavalry, but after meeting Kellogg, he chose him to go instead, mostly because Custer had been impressed by his resourcefulness with a telegraph key.

That one chance event in the winter of 1876, took Kellogg in an unexpected direction…toward the Little Big Horn. When Custer led his soldiers out of Fort Abraham Lincoln and headed west for Montana on May 31, Kellogg rode with him. During the next few weeks, Kellogg filed three dispatches from the field to the Bismarck Tribune, which in turn passed the stories on to the New York Herald. Wanting to make sure the word got out, Custer also sent three anonymous reports on his progress to the Herald. Kellogg’s first dispatches, dated May 31 and June 12, recorded the progress of the expedition westward. His final report, dated June 21, came from the army’s camp along the Rosebud River in southern Montana, not far from the Little Big Horn River. “We leave the Rosebud tomorrow,” Kellogg wrote, “and by the time this reaches you we will have met and fought the red devils, with what result remains to be seen.” The results, of course, were disastrous. Four days later, Sioux and Cheyenne warriors wiped out Custer and his men along the Little Big Horn River. Kellogg was the only journalist to witness the final moments of Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Had he been able to file a story he would have become a national celebrity, but Kellogg did not live to tell the tale, he died alongside Custer’s soldiers.

On July 6, the Bismarck Tribune printed a special extra edition with a top headline reading: “Massacred: Gen. Custer and 261 Men the Victims.” Further down in the column, in substantially smaller type, a sub-headline reported: “The Bismarck Tribune’s Special Correspondent Slain.” The article went on to report, “The body of Kellogg alone remained unstripped of its clothing, and was not mutilated.” The reporter speculated that this

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

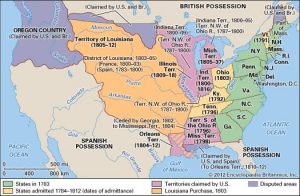

From the time the United States first declared their independence, there was a dispute over the border between the United States and its northern neighbor, Canada. In 1818, the situation finally got to a point whereby a final decision had to be made. It was determined that a convention needed to be held to handle the dispute. The convention, known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, was to discuss fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Treaty of 1818 was signed during the presidency of James Monroe, and it resolved the boundary between the United States and Canada, then owned by the United Kingdom, once and for all. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and also took in New Caledonia, near Australia.

From the time the United States first declared their independence, there was a dispute over the border between the United States and its northern neighbor, Canada. In 1818, the situation finally got to a point whereby a final decision had to be made. It was determined that a convention needed to be held to handle the dispute. The convention, known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, was to discuss fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Treaty of 1818 was signed during the presidency of James Monroe, and it resolved the boundary between the United States and Canada, then owned by the United Kingdom, once and for all. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and also took in New Caledonia, near Australia.

It was ultimately decided that the boundary line should be a straight one, because it would be easier to survey. The prior boundaries were based on watersheds, and were difficult to survey. The treaty marked both the United Kingdom’s last permanent major loss of territory in what is now the Continental United States and the United States’ only permanent significant cession of North American territory to a foreign power. Britain ceded all of Rupert’s Land south of the 49th parallel and west to the Rocky Mountains, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude, while the United States ceded the northernmost tip of the territory of Louisiana above the 49th parallel.

Of course, the prior border from the Great Lakes to the east coast, was already established, so it isn’t straight, but the northwestern border is a straight line. I always thought that was odd, and didn’t know why it was that way. I don’t know if I was not paying attention in history class, which was not my favorite subject in my youth, although I don’t really know why it wasn’t, because now I find it quite fascinating. It’s interesting to find out that the northern border was simply a matter of convenience, and a bit of the barter system, if you will. In order to solve the border war, of sorts, Canada (United Kingdom) gave a little, and the United States gave a little. The end result was a clear cut border, and really, peaceful neighbors. I think the was a good way to settle things.

Of course, the prior border from the Great Lakes to the east coast, was already established, so it isn’t straight, but the northwestern border is a straight line. I always thought that was odd, and didn’t know why it was that way. I don’t know if I was not paying attention in history class, which was not my favorite subject in my youth, although I don’t really know why it wasn’t, because now I find it quite fascinating. It’s interesting to find out that the northern border was simply a matter of convenience, and a bit of the barter system, if you will. In order to solve the border war, of sorts, Canada (United Kingdom) gave a little, and the United States gave a little. The end result was a clear cut border, and really, peaceful neighbors. I think the was a good way to settle things.