Politics

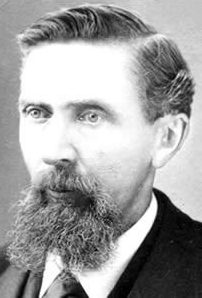

Hitler was undoubtedly one of the most horrible dictators of all time, but what prompted him to become the evil man he was. The story actually begins before Hitler was even born. In 1868, a baby named Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt, Germany, on March 23, the son of a royal notary and law counselor. My guess is that he had a fairly normal childhood…at least until his mother died when he was just ten years old. That may not seem like an event that was unique to Eckart, but somehow it was different, or would become different. Eckart’s life was further complicated when his father died seventeen years later in 1895. At this point, Eckart inherited a considerable sum of money, and started to study medicine in Munich. That would be the last of his somewhat normal life. He spent his father’s money very quickly, and recklessly.

Hitler was undoubtedly one of the most horrible dictators of all time, but what prompted him to become the evil man he was. The story actually begins before Hitler was even born. In 1868, a baby named Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt, Germany, on March 23, the son of a royal notary and law counselor. My guess is that he had a fairly normal childhood…at least until his mother died when he was just ten years old. That may not seem like an event that was unique to Eckart, but somehow it was different, or would become different. Eckart’s life was further complicated when his father died seventeen years later in 1895. At this point, Eckart inherited a considerable sum of money, and started to study medicine in Munich. That would be the last of his somewhat normal life. He spent his father’s money very quickly, and recklessly.

With his money gone, Eckart quit school, and began work as a poet, playwright, and journalist. He moved to Berlin in 1899, where he wrote a number of plays, often with autobiographical traits. Apparently, he was about the only one interested in his plays, because despite becoming the protegé of Graf Georg von Hülsen-Haeseler, the artistic director of the royal theaters, he never was successful as a playwright. Taking his madness one step further, he blamed his failure on society. This was the beginning of the insanity that became Dietrich Eckart. Later on, Eckart developed an ideology of a “genius higher human,” after reading earlier writings by Lanz von Liebenfels. Eckart saw himself like Arthur Schopenhauer and Angelus Silesius, and also became fascinated by Mayan beliefs, but never had much sympathy for the scientific method. That makes sense, because he seemed to want to make up his own truths. Eckart also loved and strongly identified with Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt.

In 1913, when he moved back to Munich, he joined up with Rudolf von Sebottendorff’s right wing Thule Society, and became very politically active. He wrote the nationalist play “Heinrich der Hohenstaufe” (“Heinrich of the High Baptism”), in which he made the claim to world leadership for the German people, craziness that he would eventually pass along to Hitler. Soon he became the editor of the anti-semetic periodical Auf gut Deutsch. Eckart opposed the Treaty of Versailles, which he described as treasonous, and instead spread the so-called Dolchstoßlegende, which stated that the social democrats and Jews were to blame for Germany’s defeat in World War I. He was involved in the founding Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers’ Party) together with Gottfried Feder and Anton Drexler in 1919, which later on was renamed Nationalsozialistische deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party, NSDAP). He invented and published the NSDAP’s own periodical Völkischer Beobachter, and also wrote the songtext “Deutschland erwache” (Germany awake), which became the anthem of the Nazi party.

Adolf Hitler was born April 20, 1889, just a few years before Eckart’s dad’s passing. During a speech he gave before party members on August 14 1919, Eckart met Adolf Hitler. He exerted considerable influence on Hitler in the following years. Hitler looked at him as his “fatherly friend.” On November 9 1923, Eckart was involved in  the Nazi party’s failed Beer Hall Putsch,as was Hitler. They were arrested and sent to Landsberg prison along with other party officials, but he was released again soon due to illness. He died of a heart attack caused by a morphine addiction in Berchtesgaden on December 26, 1923. Hitler later dedicated the first volume of Mein Kampf to Eckart, and also named the Waldbühne in Berlin “Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne” when it was first opened for the 1936 Summer Olympics. In 1925, Eckarts unfinished essay, Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin. Zwiegespräch zwischen Hitler und mir (“Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin. Dialogues between Hitler and me”), was posthumously published, although it has been shown that it the dialogues were an invention. The essay was, in fact, written by Eckart alone. I don’t know what Hitler would have been like had e not met Eckart. My guess is that the evil ideas Hitler had were there before their meeting, but I do believe that Eckart had a great influence on Hitler,and probably helped formulate some of the evil that was to come.

the Nazi party’s failed Beer Hall Putsch,as was Hitler. They were arrested and sent to Landsberg prison along with other party officials, but he was released again soon due to illness. He died of a heart attack caused by a morphine addiction in Berchtesgaden on December 26, 1923. Hitler later dedicated the first volume of Mein Kampf to Eckart, and also named the Waldbühne in Berlin “Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne” when it was first opened for the 1936 Summer Olympics. In 1925, Eckarts unfinished essay, Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin. Zwiegespräch zwischen Hitler und mir (“Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin. Dialogues between Hitler and me”), was posthumously published, although it has been shown that it the dialogues were an invention. The essay was, in fact, written by Eckart alone. I don’t know what Hitler would have been like had e not met Eckart. My guess is that the evil ideas Hitler had were there before their meeting, but I do believe that Eckart had a great influence on Hitler,and probably helped formulate some of the evil that was to come.

My great grandparents, Carl and Henriette (Hensel) Schumacher immigrated to the United States from Germany, in 1884 and 1882 respectively. It was an amazing time for them. The United States was a whole new world, and for those who came, the land of opportunity. By 1886, they were married and ready to start a family. My grandmother, Anna Schumacher was born in 1887, followed by siblings Albert, Mary (who died before she was 3), Mina, Fred, Bertha, and Elsa, who was born in 1902.

My great grandparents, Carl and Henriette (Hensel) Schumacher immigrated to the United States from Germany, in 1884 and 1882 respectively. It was an amazing time for them. The United States was a whole new world, and for those who came, the land of opportunity. By 1886, they were married and ready to start a family. My grandmother, Anna Schumacher was born in 1887, followed by siblings Albert, Mary (who died before she was 3), Mina, Fred, Bertha, and Elsa, who was born in 1902.

By 1914, World War I broke out, following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. The government of the United States was understandably nervous about the German immigrants now living in in America. It didn’t matter that many of these people had been living in the united States for a long time, and some had become citizens, married, and had families. The government was still nervous, and I can understand how that could be, because we have the same problem these days with the Muslim nations. Still, when I think about the fact that these were my sweet, kind, and loving, totally Lutheran great grandparents, I find it hard to believe that anyone could be nervous about them. Apparently, I was right, because to my knowledge, they were never detained in any of the internment camps, nor were they even threatened with it.

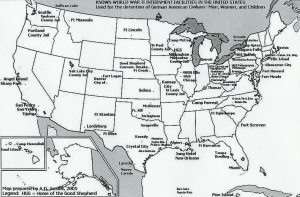

Nevertheless, there were German nationals, and even naturalized citizens who faced possible detention during  World War I and World War II. By World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared Presidential Proclamation 2526, the legal basis for internment under the authority of the Alien and Sedition Acts. With the United States’ entry into World War I, the German nationals were automatically classified as “enemy aliens.” Two of the four main World War I-era internment camps were located in Hot Springs, North Carolina and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer wrote that “All aliens interned by the government are regarded as enemies, and their property is treated accordingly.”

World War I and World War II. By World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared Presidential Proclamation 2526, the legal basis for internment under the authority of the Alien and Sedition Acts. With the United States’ entry into World War I, the German nationals were automatically classified as “enemy aliens.” Two of the four main World War I-era internment camps were located in Hot Springs, North Carolina and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer wrote that “All aliens interned by the government are regarded as enemies, and their property is treated accordingly.”

By the time of World War II, the United States had a large population of ethnic Germans. Among residents of the United States in 1940, more than 1.2 million persons had been born in Germany, 5 million had two native-German parents, and 6 million had one native-German parent. Many more had distant German ancestry. With that many people of German ancestry, it seems impossible that they could have detained all of them. Nevertheless, at least 11,000 ethnic Germans, overwhelmingly German nationals were detained during World War II in the United States. The government examined the cases of German nationals individually, and detained relatively few in internment camps run by the Department of Justice, as per its responsibilities under the Alien and Sedition Acts. To a much lesser extent, some ethnic German United States citizens were classified as suspect after due process and also detained. There were also a small proportion of Italian nationals  and Italian Americans who were interned in relation to their total population in the United States. The United States had allowed immigrants from both Germany and Italy to become naturalized citizens, which many had done by then. It was much less likely for those people to be detained, if they had already become citizens. In the early 21st century, Congress considered legislation to study treatment of European Americans during World War II, but it did not pass the House of Representatives. Activists and historians have identified certain injustices against these groups. I suppose that some injustices were done, but those were times of war and strong measures were needed.

and Italian Americans who were interned in relation to their total population in the United States. The United States had allowed immigrants from both Germany and Italy to become naturalized citizens, which many had done by then. It was much less likely for those people to be detained, if they had already become citizens. In the early 21st century, Congress considered legislation to study treatment of European Americans during World War II, but it did not pass the House of Representatives. Activists and historians have identified certain injustices against these groups. I suppose that some injustices were done, but those were times of war and strong measures were needed.

Following instructions and paying close attention to those instructions are crucial to the safe operation of a plane, especially at take offs and landings. When the pilot of Comair Flight 5191 taxied to the runway of his takeoff, something went horribly wrong. He was told to proceed to Runway 22, but he turned one lane too early, and ended up taking off on Runway 26, which was too short for a safe take off of a plane of that size. Comair 1591, was a CRJ-100ER plane that was carrying 47 passengers and 3 crew members. Instead of using runway 22 as expected, they used runway 26 which had too short of a path for a safe takeoff, even though Captain Jeffrey Clay confirmed using runway 22. He inadvertently took a left too early according to the map. At Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky, on August 27, 2006, 49 of the 50 passengers and crew died while taking off from the airport. It’s hard to say at what point the pilot knew he was in trouble, but as the plane reached the end of the runway, they knew that there had not been enough time to gt the plane up to speed,and they simply couldn’t get enough lift to get it safely in the air. “They must have almost cleared the fence because only the top of it was missing and then the tips of some trees further out were also burnt off,” said Nick Bentley, who owns the 115-acre farm where the plane crashed, referring to an 8-foot metal fence that separates his property from the airport’s 3,500-foot runway.

Following instructions and paying close attention to those instructions are crucial to the safe operation of a plane, especially at take offs and landings. When the pilot of Comair Flight 5191 taxied to the runway of his takeoff, something went horribly wrong. He was told to proceed to Runway 22, but he turned one lane too early, and ended up taking off on Runway 26, which was too short for a safe take off of a plane of that size. Comair 1591, was a CRJ-100ER plane that was carrying 47 passengers and 3 crew members. Instead of using runway 22 as expected, they used runway 26 which had too short of a path for a safe takeoff, even though Captain Jeffrey Clay confirmed using runway 22. He inadvertently took a left too early according to the map. At Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky, on August 27, 2006, 49 of the 50 passengers and crew died while taking off from the airport. It’s hard to say at what point the pilot knew he was in trouble, but as the plane reached the end of the runway, they knew that there had not been enough time to gt the plane up to speed,and they simply couldn’t get enough lift to get it safely in the air. “They must have almost cleared the fence because only the top of it was missing and then the tips of some trees further out were also burnt off,” said Nick Bentley, who owns the 115-acre farm where the plane crashed, referring to an 8-foot metal fence that separates his property from the airport’s 3,500-foot runway.

Shortly after 6am, Comair flight 1591 crashed in a field just half a mile from the Blue Grass Airport in an area of Kentucky known for its horse farms and the Keeneland Race Course. The plane was traveling from Lexington to Atlanta, when it went down. Peggy Young, who lives on Rice Road, near the area where the plane came down, said that just after 6am she and her husband Michael were awakened by the sound of the crash. “There was a loud explosion,” she said in a telephone interview. “We thought it was just a storm, but then we thought it was too loud to be a storm because it had just barely rained. We just were sleeping in when the phone rang and it was Keeneland security and they told my husband there had been an airplane crash.”

First Officer James Polehinke was the only survivor of the crash. He suffered broken bones, a collapsed lung,

and severe bleeding. In the end, the ultimate blame was put on the captain, because he didn’t abort liftoff despite questioning his surroundings. Nevertheless, the airport was found to be using outdated maps and had needed to improve runway markings and conditions.So in reality there was blame to go around, and because of the errors, 49 people lost their lives that day in August, twelve years ago. “The whole airport shut down from Aug. 18 to 20,” said Brian Ellestad, the director of marketing and community relations.

and severe bleeding. In the end, the ultimate blame was put on the captain, because he didn’t abort liftoff despite questioning his surroundings. Nevertheless, the airport was found to be using outdated maps and had needed to improve runway markings and conditions.So in reality there was blame to go around, and because of the errors, 49 people lost their lives that day in August, twelve years ago. “The whole airport shut down from Aug. 18 to 20,” said Brian Ellestad, the director of marketing and community relations.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

The most famous of these female spies was Belle Boyd…born Marie Isabella Boyd. She began spying for the Confederacy when Union troops invaded her Martinsburg, Virginia home in 1861. One of the Federal soldiers manhandled her mother, and Boyd shot and killed him. She was exonerated in the soldier’s death, and an emboldened Boyd managed to befriend the Union soldiers left to guard her, and used her slave, Eliza, to pass information confided in her by the soldiers along to Confederate officers. Boyd was caught at her first attempt at spying, and threatened with death, but she did not stop her activities. She vowed to find a better way instead. She began eavesdropping on union officers staying at her father’s hotel. She learned enough to inform General Stonewall Jackson about their regiment and activities. Taking no chances, this time, Boyd delivered her intelligence firsthand, moving through Union lines, and reportedly drawing close enough to the action to return with bullet holes in her skirts. The information she provided allowed the Confederate army to advance on Federal troops at Fort Royal. Boyd’s daring acts of espionage soon caught up with her again and when a beau gave her up to Union authorities in 1862, she was arrested and held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington for a month. Then she released, but found herself in the arrested again soon after. Once again, she managed to be set free, and this time she traveled to England, where amazingly, she married not a Confederate soldier, but a Union officer.

Boyd wasn’t the only spy in the Civil War. Another famous female spy was nicknamed “Crazy Bet,” but her real  name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

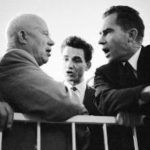

The debate between capitalism and communism is not new, and in fact has been going on for a long time. Possibly one of the strangest debates, known as the “kitchen debate” was between Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The debate was heated at times, but what was strangest about the debate was the fact that it took place in the middle of a model kitchen set up for an exhibit. Why they would have such a discussion in a model kitchen at a national exhibit is the really beyond me, but that is where it took place.

The debate between capitalism and communism is not new, and in fact has been going on for a long time. Possibly one of the strangest debates, known as the “kitchen debate” was between Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The debate was heated at times, but what was strangest about the debate was the fact that it took place in the middle of a model kitchen set up for an exhibit. Why they would have such a discussion in a model kitchen at a national exhibit is the really beyond me, but that is where it took place.

The so-called “kitchen debate” became one of the most famous episodes of the Cold War, and many think it might have really led to fighting words, had it not been for the two men controlling their tempers in the end. The meeting was set up in late 1958. In an effort to draw the two nations closer together, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to set up national exhibitions in each other’s nation as part of their new emphasis on cultural exchanges. The Soviet exhibition opened in New York City in June 1959, and the United States exhibition opened in Sokolniki Park in Moscow in July. On July 24, before the Moscow exhibit was officially opened to the public, Vice President Nixon served as a host for a visit by Soviet leader Khrushchev. As Nixon led Khrushchev through the American exhibition, the Soviet leader’s famous temper began to flare. When Nixon demonstrated some new American color television sets, Khrushchev launched into an attack on the so-called “Captive Nations Resolution” passed by the United Stares Congress just days before. The resolution condemned the Soviet control of the “captive” peoples of Eastern Europe and asked all Americans to pray for their deliverance. I don’t suppose that resolution set well with Khrushchev, and coming right before the exhibition probably set the whole debate in motion.

After denouncing the resolution, Khrushchev then sneered at the United States technology on display, saying that the Soviet Union would have the same sort of gadgets and appliances within a few years. Nixon, was not a man to back down from a debate, so he cane right back and goaded Khrushchev by stating that the Russian leader should “not be afraid of ideas. After all, you don’t know everything.” The Soviet leader snapped at Nixon, “You don’t know anything about communism–except fear of it.” With a small army of reporters and photographers following them, Nixon and Khrushchev continued their argument in the kitchen of a model home built in the exhibition. With their voices rising and fingers pointing, the two men went at each other. I’m sure it was quite a show. Nixon suggested that Khrushchev’s constant threats of using nuclear missiles could lead to war, and he chided the Soviet for constantly interrupting him while he was speaking. Taking these words as a threat, Khrushchev warned of “very bad consequences.” Perhaps feeling that the exchange had gone too far, the Soviet leader then noted that he simply wanted “peace with all other nations, especially America.” Nixon,  feeling slightly embarrassed said that he had probably not “been a very good host.” The debate, so quickly inflamed, fizzled in much the same way…at least between the two men…not so much the media.

feeling slightly embarrassed said that he had probably not “been a very good host.” The debate, so quickly inflamed, fizzled in much the same way…at least between the two men…not so much the media.

The “kitchen debate” was front-page news in the United States the next day. For a few moments, in the confines of a “modern” kitchen, the diplomatic gloves had come off and America and the Soviet Union had verbally jousted over which system was superior…communism or capitalism. As with so many Cold War battles, however, there was no clear winner…except perhaps for the United States media, which had a field day with the dramatic encounter. It was the sensationalism that the news media craves.

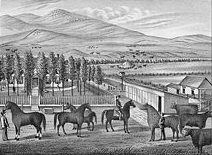

When Conrad Kohrs, immigrated to the United States at the age of 15, he was seeking his fortune like so many other immigrants were. The year was 1850, and while it is odd these days to think of a 15 year old boy immigrating to America alone now, it wasn’t entirely unheard of then. Kohrs was a native of Denmark, and had planned to head west to make his fortune in gold or silver. Unfortunately, while he had some small success in California and British Columbia, try as he might, the “big strike” always eluded Kohrs.

When Conrad Kohrs, immigrated to the United States at the age of 15, he was seeking his fortune like so many other immigrants were. The year was 1850, and while it is odd these days to think of a 15 year old boy immigrating to America alone now, it wasn’t entirely unheard of then. Kohrs was a native of Denmark, and had planned to head west to make his fortune in gold or silver. Unfortunately, while he had some small success in California and British Columbia, try as he might, the “big strike” always eluded Kohrs.

Kohrs tended to follow the crowd, and in 1862, he joined the latest western gold rush and headed for western Montana, where rich gold deposits had been found at Grasshopper Creek. It might be true that gold was plentiful at Grasshopper Creek, but Kohrs realized that he could make more money mining the miners than mining for gold. Miners need lots of supplies, and the man who was able to supply the needs, was the one who made money. He established a butcher shop in the mining town of Bannack and began to prosper.

His work as a butcher led Kohrs into the cattle business. Cattle were a big commodity, being in relatively short supply in frontier Montana. Much has changed today, and Kohrs had a big part in that. Kohrs traveled around the territory to purchase prime animals. He had several brushes with the highwaymen who plagued the isolated roads of Montana. Determined to stop these murderous bandits, Kohrs joined a group of Virginia City vigilantes, and helped track down and hang the outlaws. By 1864, robberies in the territory had plummeted. Proper or not, vigilante justice, got the point across very well.

Whether he was good at being part of a vigilante group or not, it couldn’t be what made his living. Kohrs began shifting the focus of his meat processing business to the supply side. In 1864, he established a large ranch near the town of Deer Lodge, where he fattened his cattle for market. Kohrs was pretty much the only major rancher in the western region of the territory. This caused his business to boom as Montana grew. As always happens, eventually, competition from cattle driven overland into the territory from Texas began to challenge Kohrs’ monopoly. Nevertheless, he continued to prosper, and remained the largest cattle rancher in Montana for several decades.

Kohrs entered the political arena in 1885, translating his economic strength into political power. He was elected to the Montana Territorial Legislature. Kohrs and his fellow ranchers had considerable influence over Montana in the years to come, and Kohrs went on to become a state senator in 1902. The big ranchers never had a free hand in Montana, however, because mining interests and farmers always kept the ranchers in check, but it wasn’t for a lack of trying. Kohrs was widely celebrated as one of the greatest pioneers in Montana history. He died on July 23, 1920 at the age of 85 in Helena.

A number of years ago, I requested my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer’s military records from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Saint Louis, Missouri, only to be told that the records had been destroyed by a fire in 1973. I hadn’t heard about this before, and so really knew nothing about the details, except that I would never be able to find any more records of my dad’s military service during World War II, other than the ones we had, which was comparatively little. I wondered how it could be that the only military records for all those men were stored in one building, with no back up records. I know computers were not used as often, but there were things like microfiche back then. Nevertheless, the records were lost…and the loss felt devastating to me.

A number of years ago, I requested my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer’s military records from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Saint Louis, Missouri, only to be told that the records had been destroyed by a fire in 1973. I hadn’t heard about this before, and so really knew nothing about the details, except that I would never be able to find any more records of my dad’s military service during World War II, other than the ones we had, which was comparatively little. I wondered how it could be that the only military records for all those men were stored in one building, with no back up records. I know computers were not used as often, but there were things like microfiche back then. Nevertheless, the records were lost…and the loss felt devastating to me.

When I heard about the fire that destroyed my dad’s records, it all seemed like the distant past, but in reality, it was during my high school years. Then, it just seemed like a bad dream…a nightmare really. I couldn’t believe that there was no way to get copies of those records. My dad’s pictures, one of which was signed by the pilot of Dad’s B-17, on which Dad was a top turret gunner. Those pictures and the few records are all we have of his war years, and to this day, that makes me sad.

The fire broke out on July 13, 1973 and quickly engulfed the top floor of the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). In less 15 minutes from the time the fire was reported, the first firefighters arrived at the sixth floor of the building, only to be forced to retreat as their masks began to melt on their faces. The fire was that hot!! There was just no way to successfully save the documents that were stored there. The fire burned out of control for more than 22 hours…even with 42 fire districts attempting to extinguish the flames. It was not until five days later that it was finally completely out. Besides the burning of records, the tremendous heat of the fire warped shelves while water damage caused some surviving documents to carry mold.

About 73% to 80% of the approximately 22 million individual Official Military Personnel Files stored in the building were destroyed. The records lost were those of former members of the U.S. Army, the Army Air Force, and the Air Force who served between 1912 and 1963. My dad joined the Army Air Force on March 19, 1943 and was discharged October 3, 1945. Many of the documents lost were from those years. They were gone, and there was no way to get them back. The National Personnel Records Center staff continues to work to preserve the damaged records that ere saved. There were about 6.5 million records recovered since the fire.

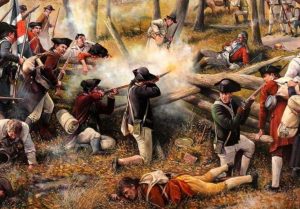

I think that one of the things most people look forward to in mid-summer is Independence Day. Of course, the normal holiday for many people is filled with picnics, fireworks, and celebration of our freedom. Many of us consider the price that was paid in the Revolutionary War to win our freedom from England, and then our thoughts move on to the many wars the United Stares has fought into keep our freedoms, and to win freedom for oppressed nations around the world. It’s a noble thing our soldiers do, often with little thanks from those they help. And all too often, their work is quickly forgotten or even protested by those who do not understand how important it is not to give away our freedoms to those who do not share our values.

I think that one of the things most people look forward to in mid-summer is Independence Day. Of course, the normal holiday for many people is filled with picnics, fireworks, and celebration of our freedom. Many of us consider the price that was paid in the Revolutionary War to win our freedom from England, and then our thoughts move on to the many wars the United Stares has fought into keep our freedoms, and to win freedom for oppressed nations around the world. It’s a noble thing our soldiers do, often with little thanks from those they help. And all too often, their work is quickly forgotten or even protested by those who do not understand how important it is not to give away our freedoms to those who do not share our values.

Whatever a person’s politics are, or even if they don’t participate at all, pretty much  everyone celebrates Independence Day. It is a beloved holiday in this country. It’s a day to celebrate who we are as a nation….the land of the free, and the home of the brave. The fireworks are to remember the rockets that were used in the battle for our independence. The patriot soldiers fought hard against the British, never giving up, even if they lost their lives in the battle. The danger was worth the risk. They could no longer be slaves to the British. They were being taxed without representation, and unmercifully. It was time for the United States to become it’s own nation. I don’t think the British have any inkling that they would lose the Revolutionary War. It was like being beaten by your child. How could that “kid” actually have grown enough to beat them…and yet, the “kid” had not only fought against the “parent” country, but they won. They fought and now we’re free!!

everyone celebrates Independence Day. It is a beloved holiday in this country. It’s a day to celebrate who we are as a nation….the land of the free, and the home of the brave. The fireworks are to remember the rockets that were used in the battle for our independence. The patriot soldiers fought hard against the British, never giving up, even if they lost their lives in the battle. The danger was worth the risk. They could no longer be slaves to the British. They were being taxed without representation, and unmercifully. It was time for the United States to become it’s own nation. I don’t think the British have any inkling that they would lose the Revolutionary War. It was like being beaten by your child. How could that “kid” actually have grown enough to beat them…and yet, the “kid” had not only fought against the “parent” country, but they won. They fought and now we’re free!!

Since they won, we have something wonderful to celebrate on July 4th…our independence. When I think of the alternative, I cringe. It’s not that I hate England, because, in fact, I don’t. I have relatives there, including in the royal family, so I don’t hate England, but we were just different. Our values and ideals were different. We could not peacefully co-exist the way we were, And yet, now that we are two separate nations, we are allies. We had to be equals in order to be allies. We had to have their respect, as a free nation, and we got it. We have been a respected, free nation since that day…July 4, 1776. And that is why we still celebrate our independence. Happy Independence Day everyone!!

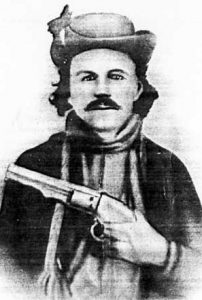

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

When the Civil War broke out, Bob Lee, by that time married with three children, quickly joined the Confederate Army, serving with the Ninth Texas Cavalry. Other young men in the area, including the Maddox brothers…John, William, and Francis; their cousin Jim Maddox, and several of the Boren boys, also joined the Ninth. Towards the end of the war, Bob heard that the Union League, an organization that worked for the protection of the blacks and Union sympathizers, had set up its North Texas headquarters at Pilot Grove, just about seven miles away from the Lee family homes.

The head of the Union League was a man named Lewis Peacock, who had arrived in Texas in 1856 and lived just south of Pilot Grove. Federal Troops were sent to Texas to aid in reconstruction efforts. By the time the Confederate soldiers returned to their homes in northeast Texas, the area was already in heavy conflict. Whether they owned slaves or not, most area residents resented the intrusion of Reconstruction ideals and new laws. When Bob Lee returned home, he was seen as a natural leader for the “Civil War” that was still being fought in northeast Texas.

To Peacock, Lee was seen as a threat to his cause and to reconstruction itself. To remove this threat, the Union League conceived of the idea to extort money from Lee. Peacock and his cohorts arrived at Lee’s house one night and “arrested” him, allegedly for crimes that he had committed during the Civil War. Lee would later say that he recognized the men as Lewis Peacock, James Maddox, Bill Smith, Sam Bier, Hardy Dial, Doc Wilson, and Israel Boren. Stating to Lee that he was to be taken into Sherman, they instead stopped in Choctaw Creek bottoms, where they took Lee’s watch, a $20 gold coin, and forced him to sign a promissory note for $2,000. The Lee’s refused to pay the note, bringing suit in Bonham, Texas and winning the case. This was the start of an all-out war, known as the Lee-Peacock Feud.

Both men gathered their friends and sympathizers and from 1867 through June 1869, a second “Civil War” raged in northeast Texas. An estimated 50 men losing their lives. By the summer of 1868, it had become so heated that the Union League requested help from the Federal Government, to which General JJ Reynolds posted a reward of $1,000 for the capture of Bob Lee. In late February, 1867, Lee was in a store in Pilot Grove when he ran across Jim Maddox, one of the men who had kidnapped him. Confronting Maddox, Lee offered Maddox a gun so they could fight. When Lee turned around to walk away, a bullet grazed his ear and head and he fell to the ground unconscious. Lee was taken to Dr William H Pierce, who treated him in his home. A report went to Austin to the Headquarters of the Fifth Military District under command of General John J. Reynolds, and the following entry was made in his ledger: “Murder and Assaults with Intent to Kill”, listed as criminals were James Maddox and John Vaught, listed as injured was Robert Lee. The charge: “Assault with intent to murder.” The result: “Set aside by the Military”. A few days later, on February 24, 1867, while Lee was still, convalescing in Pierce’s home, the doctor was shot to death by Hugh Hudson, a known Peacock man. Lee swore to avenge Pierce’s death and as word spread to both sides of the conflict, neighbors in the thickets of Four Corners began to arm themselves.

Hugh Hudson, the doctor’s killer was later shot at Saltillo, a teamster’s stop on the road to Jefferson. The feud had begun in full force. In 1868, Lige Clark, Billy Dixon, Dow Nance, Dan Sanders, Elijah Clark, and John Baldock were killed and many others wounded. Even Peacock suffered a wound at the hands of Lee’s followers. On August 27, 1868, General J. J. Reynolds issued the $1,000 reward for Bob Lee, dead or alive, an act that attracted bounty hunters from all over the country to the “Four Corners.” Three of these men, union sympathizers from Kansas, converged on the area in the early spring of 1869 to try to capture Lee. Instead, all three were found dead on the road. Bob Lee, in the meantime, had set up a hideout in the “Wildcat Thicket.”

General JJ Reynolds responded by dispatching the Fourth United States Cavalry to search for Lee and attempt to settle the trouble in the area. As they began a search from house to house for Lee, in which several gun battles ensued and several men were killed. In the end, one of Bob Lee’s “supporters,” a man named Henry Boren, betrayed him to the cavalry who shot down Lee on May 24, 1869. Later, Boren was shot down by his  own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

As the Texas authorities had hoped, the killing of Lee began to dissolve the heated dispute, as many men scattered to other parts of the state. Though they were fewer in number, the “war” continued for two years, as more men were killed in both the four-corners region and other parts of the state. It wouldn’t be until Lewis Peacock was shot on June 13, 1871, that the feud finally ended.

World War II saw many changes in how women were viewed in the normally male-dominated world. With so many men off fighting the war, the women stepped up to do the jobs of riveters in the shipyards, and they stepped up in many other occupations too. If there are no men to do the jobs, someone had to keep the country running, and the United States found out that women were up for the task. I don’t suppose that everyone thought that women could do it, but they simply had no choice. World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. This war taught us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism.

World War II saw many changes in how women were viewed in the normally male-dominated world. With so many men off fighting the war, the women stepped up to do the jobs of riveters in the shipyards, and they stepped up in many other occupations too. If there are no men to do the jobs, someone had to keep the country running, and the United States found out that women were up for the task. I don’t suppose that everyone thought that women could do it, but they simply had no choice. World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. This war taught us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism.

Prior 1942, the only way for women to be involved in the service was as an Army Nurse, in the Army Nurse Corps, but early in 1941 Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts met with General George C. Marshall, the Army’s Chief of Staff, and told him that she intended to introduce a bill to establish an Army women’s corps, separate and distinct from the existing Army Nurse Corps. Congress approved that bill on May 14, 1942, and the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was born. The WAAC bill became law on May 15, 1942. Congressional opposition to the bill centered around southern congressmen. With women in the armed services, one representative asked, “Who will then do the cooking, the washing, the mending, the humble homey tasks to which every woman has devoted herself; who will nurture the children?” These days he would have been run out of Congress for having backward ideas but it was a different time, and one that some women of today truly miss…especially young mothers.

After a long and bitter debate which filled ninety-eight columns in the Congressional Record, the bill finally passed the House 249 to 86. The Senate approved the bill 38 to 27 on May 14. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law the next day, he set a recruitment goal of 25,000 for the first year. WAAC recruitment topped that goal by November of 1942, at which point Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson authorized WAAC enrollment at 150,000, the original ceiling set by Congress. The day the bill became law, Stimson appointed Oveta Culp Hobby as Director of the WAAC. As chief of the Women’s Interest Section in the Public Relations Bureau at the War Department, Hobby had helped shepherd the WAAC bill through Congress. She had impressed both the media and the public when she testified in favor of the WAAC bill in January. In the words of the Washington Times Herald, “Mrs. Hobby has proved that a competent, efficient woman who works longer days than the sun does not need to look like the popular idea of a competent, efficient woman.” Women would go on to not only become competent and efficient, but requested…sometimes above the men!!

So, what led to the Army’s decision to enlist women during World War II? The answer is simple. The “unfathomable” became reality, as the Army struggled to fulfill wartime quotas from an ever-shrinking pool of candidates. By mid-1943, the Army was simply running out of eligible white men to enlist. The Army could scarcely spare those men already in the service for non-combatant duties. General Dwight D. Eisenhower remarked: “The simple headquarters of a Grant or Lee were gone forever. An Army of filing clerks, stenographers, office managers, telephone operators, and chauffeurs had become essential, and it was scarcely

less than criminal to recruit these from needed manpower when great numbers of highly qualified women were available.” While women played a vital role in the success of World War II, their admission into combat roles would not come for many years, and many weren’t sure it was a good idea when it did. The WAC, as a branch of the service, was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units.

less than criminal to recruit these from needed manpower when great numbers of highly qualified women were available.” While women played a vital role in the success of World War II, their admission into combat roles would not come for many years, and many weren’t sure it was a good idea when it did. The WAC, as a branch of the service, was disbanded in 1978 and all female units were integrated with male units.