History

With so much technology these days, the things that we used to do the old-fashioned way have begun to get lost in the annals of time. Some things, it seems to me would fall into the category of “good riddance,” while others fall into the category of “how sad.” I know that many people would disagree with me, but I have very little use for old-fashioned books. I know that is an odd one, but once you have read the book, how many people will go back and read it again…even the classics. Maybe a few people will, but with so many books to read, most will not. That is why e-books and audible books make perfect sense to me.

With so much technology these days, the things that we used to do the old-fashioned way have begun to get lost in the annals of time. Some things, it seems to me would fall into the category of “good riddance,” while others fall into the category of “how sad.” I know that many people would disagree with me, but I have very little use for old-fashioned books. I know that is an odd one, but once you have read the book, how many people will go back and read it again…even the classics. Maybe a few people will, but with so many books to read, most will not. That is why e-books and audible books make perfect sense to me.

A physical calendar is another thing that seems unnecessary to me, although I do like the pictures many of them have. The thing is that writing your schedule on a physical calendar is only helpful if you are where the calendar is. You might suggest a daily planner, but that still requires you to look at it periodically, and let’s face it. Time flies, especially during the workday. If you forget to look at that calendar, you miss your appointment.  The calendar on your phone, which as we all know is always with you, comes with a reminder that alerts you when it’s time to go to your appointment. Life is hectic, and I just don’t need the added stress of missing appointments, even now that I’m retired.

The calendar on your phone, which as we all know is always with you, comes with a reminder that alerts you when it’s time to go to your appointment. Life is hectic, and I just don’t need the added stress of missing appointments, even now that I’m retired.

I have gone shopping with a paper list, and I’m sure you have too. I have also gone to the store and forgotten my list. Then I spent my who shopping experience trying to remember what was on my list. I’ll be honest I don’t always shop with a list of any kind, but when I really need to remember something, a list is essential. Once again, I go back to my phone, because there is a note app on my phone, and you can even get an app specifically for groceries. That’s where I put the really important things, because I always have my phone with me…don’t you? You do, because really…nobody has a landline anymore.

While my dear uncle, Bill Spencer always wanted to get a letter from his loved ones, and I can totally understand why, after looking at some of the letters from my dad to his mom, from my uncle to me, and from ancestors I never met to other ancestors I never met. The point is, as my uncle put it that you can actually see their handwriting. That is truly a precious thing to have. I suppose that if I have one “old-fashioned” thing that

I could go both ways with letters would be that thing. Those handwritten letters are precious, but daily communication received quickly via text, messenger, or snap chat are very important to me too. When you have children who live far away, or as we all do, children who are very busy, those quick little messages are a great treasure. I think I will always treasure both.

I could go both ways with letters would be that thing. Those handwritten letters are precious, but daily communication received quickly via text, messenger, or snap chat are very important to me too. When you have children who live far away, or as we all do, children who are very busy, those quick little messages are a great treasure. I think I will always treasure both.

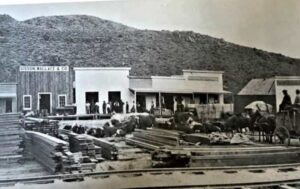

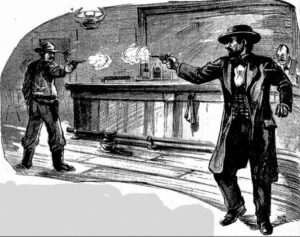

When the Transcontinental Railroad opened in 1869, the people in the east finally had the chance to take a trip into the Wild West without having to move there or plan on spending months there visiting family. I can imagine that there were mixed emotions involved as they headed out. The Western dime novels had told of wild Indians, gunslingers, bank robberies, and of course, train robberies. It was almost enough to make them question the sanity of their intended trip into the wild, but nevertheless, they went.

When the Transcontinental Railroad opened in 1869, the people in the east finally had the chance to take a trip into the Wild West without having to move there or plan on spending months there visiting family. I can imagine that there were mixed emotions involved as they headed out. The Western dime novels had told of wild Indians, gunslingers, bank robberies, and of course, train robberies. It was almost enough to make them question the sanity of their intended trip into the wild, but nevertheless, they went.

One of the great misconceptions of the Wild West is that it maybe wasn’t quite as wild as the Easterners had been told. In fact, the town of Palisade, Nevada, a state notoriously known for its wildness these days, like many other Wild West towns of the time, was actually very peaceful. In fact, the town had so few crimes that it didn’t even have an official sheriff. So, when the train began running through Palisade, and the train conductor  told the townspeople that railroad passengers were often disappointed at how these quiet towns were so different from how they were portrayed in the Western dime novels, he people of Palisade decided that something had to be done.

told the townspeople that railroad passengers were often disappointed at how these quiet towns were so different from how they were portrayed in the Western dime novels, he people of Palisade decided that something had to be done.

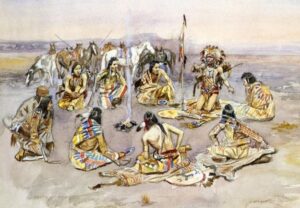

The townspeople, with the full knowledge and approval of the citizens of the town, the US Cavalry, and even a local Indian tribe, staged Western-style shootouts in the street, bank robberies, Indian battles, and whatever else they could think of. The whole purpose was to provide entertainment for the passing railroad travelers. After the train passed, life in the small town went back to its “dull, quiet, and peaceful” normal. I don’t know if the purpose was to bring in more tourists, to save face when it came to the Western dime novels, or maybe just to have a good laugh at the expense of the city-slickers. The reality is that many of the people back east, at that time, felt like their way of life was better than the “craziness” of the Wild West, and that to go have a look was a way of not only entertaining themselves, but also to prove that the West could not possibly be a peaceful place to live. Of course, while things could be violent and wild in the old West, it wasn’t always that

way. It’s also a possibility that the people had moved to the West wanted the people in the East to think that the West was a wild place, full of adventure. It was the whole purpose for going west anyway, wasn’t it…to find that adventure? Yes, that was the purpose for the move to the West. And that purpose had to be protected, by any means necessary…even theater.

way. It’s also a possibility that the people had moved to the West wanted the people in the East to think that the West was a wild place, full of adventure. It was the whole purpose for going west anyway, wasn’t it…to find that adventure? Yes, that was the purpose for the move to the West. And that purpose had to be protected, by any means necessary…even theater.

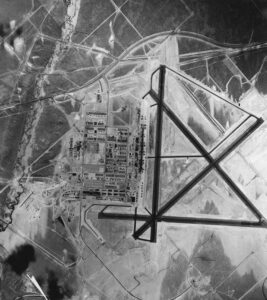

It’s hard to believe that the war my dad fought in was going on over 80 years ago. It’s also hard to believe that 80 years ago today, what is now known as Casper-Natrona County International Airport, was then known as the Casper Army Air Base. In fact, today, September 1, 1942, was the day that the “new” Army Air Base opened. The base was a training base, because as you will recall, World War II was not fought on American soil, although there was one balloon bombing incident that did reach American soil.

It’s hard to believe that the war my dad fought in was going on over 80 years ago. It’s also hard to believe that 80 years ago today, what is now known as Casper-Natrona County International Airport, was then known as the Casper Army Air Base. In fact, today, September 1, 1942, was the day that the “new” Army Air Base opened. The base was a training base, because as you will recall, World War II was not fought on American soil, although there was one balloon bombing incident that did reach American soil.

Over the years that the Casper Army Air Base was in use, over 16,000 bomber crew members were trained there. The Casper Army Air Base was one of many Army Air Force bases built during World War II. Training began a few months after the base opened. As a training hub, the base at one time had nearly 5,000 people living and working out of about 400 buildings. Many of the buildings from the old base stand today.

During the three years that the Casper Army Air Base was active, 140 Casper Army Air Base aviators died in 90 plane crashes. Of course, not all of the crashes were at the base. Most of the crashes were in Wyoming, but many occurred out of state when the fliers were on longer training flights. New crews arrived at Casper typically by train. Each crew consisted of two pilots, a navigator, a bombardier, a radioman, flight engineer, and four gunners. They immediately began a strict regimen of training. Pilot training was rigorous. The crews endured countless hours of advanced instruction in navigation, gunnery, bombing, armaments, flight engineering, and flying. They were also trained in aerial gunnery, air-to-ground gunnery, formation flying, night navigation, and of course, bombing. Joye Kading (longtime Casper Army Air Base secretary) remembered that Major General Hap Arnold once visited the base. She said, “He was so thrilled with this base and how it was operated and how careful it was, and how congenial all the people were that were working with one another.” That is truly how most people in Casper are, even today. Of course, you always find a few who don’t fit that description, but they are the rarity, and not the norm.

The base closed in 1945 and sat abandoned until the War Assets Administration turned the airfield over to civil

control in the late 1940s, and in 1949 it became Natrona County Municipal Airport. At that time, it replaced the former Casper Airport…Wardwell Field, whose runways are now streets in the town of Bar Nunn. On December 19, 2007, the name was changed to Casper-Natrona County International Airport. These days, approximately 35,000 flights go in and out of the airport every year.

control in the late 1940s, and in 1949 it became Natrona County Municipal Airport. At that time, it replaced the former Casper Airport…Wardwell Field, whose runways are now streets in the town of Bar Nunn. On December 19, 2007, the name was changed to Casper-Natrona County International Airport. These days, approximately 35,000 flights go in and out of the airport every year.

We were watching the Denver Broncos in their huge (19-3) defeat of the Kansas City Chiefs. The game had really just gotten started (it had a 4:00pm start time) when the crash, that took the life of Diana, Princess of Wales, occurred in Paris at 12:23am (4:23pm Mountain Time). The news of the tragedy was aired shortly thereafter, and by 3:00am, Paris time, she was dead. That news was announced at 6:00am Paris time.

We were watching the Denver Broncos in their huge (19-3) defeat of the Kansas City Chiefs. The game had really just gotten started (it had a 4:00pm start time) when the crash, that took the life of Diana, Princess of Wales, occurred in Paris at 12:23am (4:23pm Mountain Time). The news of the tragedy was aired shortly thereafter, and by 3:00am, Paris time, she was dead. That news was announced at 6:00am Paris time.

Diana was a distant cousin of mine…(specifically my 12th cousin 2 times removed), so the news held some significance to my family. There have been many questions concerning the crash that took Diana’s life, and while the powers that be say that they have all been answered, there are many people, including me, who still have questions. I’m sure that we will never have our questions fully answered, and I’m sure that is partly due to the fact that when it comes to Diana, we aren’t sure that the British Crown is telling us everything they know. The mere fact that Prince Charles and Princess Diana were divorced, and at that time, and to many people, his claim to the throne was in question, we naturally doubted the validity of the answers we were given. Nevertheless, no further answers will likely be forthcoming, so we will have to accept the answers we were given…or not accept them, as you please. After the divorce, Princess Diana became known as Diana, Princess of Wales, as a supposed concession by the crown.

Diana, affectionately known as “the People’s Princess,” was 36 years old at the time of her death. Her  boyfriend, the Egyptian-born socialite Dodi Fayed, and the driver of the car, Henri Paul, died as well. The lone survivor of the crash was Diana’s bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones, who was seriously injured. The car left the Ritz Paris just after midnight, intending to go to Dodi’s apartment on the Rue Arsène Houssaye. As soon as they departed the hotel, a swarm of paparazzi on motorcycles began aggressively tailing their car. About three minutes later, the driver lost control and crashed into a pillar at the entrance of the Pont de l’Alma tunnel. It was later decided that because the driver had alcohol and prescription drugs in his system, the paparazzi held no fault in the matter. That is where I disagree. While the driver had alcohol and prescription drugs in his system, he would not have felt the need to speed through the streets if the paparazzi had left them alone. As a retired insurance agent, I know contributory negligence when I see it. Nevertheless, a “formal investigation” concluded the paparazzi did not cause the collision. Dodi Fayed and Henri Paul, the driver, were pronounced dead at the scene. Diana was taken to the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital and officially declared dead at 6:00am. Diana’s former husband Prince Charles, as well as her sisters and other members of the Royal Family, arrived in Paris that morning. Diana’s body was then taken back to London.

boyfriend, the Egyptian-born socialite Dodi Fayed, and the driver of the car, Henri Paul, died as well. The lone survivor of the crash was Diana’s bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones, who was seriously injured. The car left the Ritz Paris just after midnight, intending to go to Dodi’s apartment on the Rue Arsène Houssaye. As soon as they departed the hotel, a swarm of paparazzi on motorcycles began aggressively tailing their car. About three minutes later, the driver lost control and crashed into a pillar at the entrance of the Pont de l’Alma tunnel. It was later decided that because the driver had alcohol and prescription drugs in his system, the paparazzi held no fault in the matter. That is where I disagree. While the driver had alcohol and prescription drugs in his system, he would not have felt the need to speed through the streets if the paparazzi had left them alone. As a retired insurance agent, I know contributory negligence when I see it. Nevertheless, a “formal investigation” concluded the paparazzi did not cause the collision. Dodi Fayed and Henri Paul, the driver, were pronounced dead at the scene. Diana was taken to the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital and officially declared dead at 6:00am. Diana’s former husband Prince Charles, as well as her sisters and other members of the Royal Family, arrived in Paris that morning. Diana’s body was then taken back to London.

Because Diana was one of the most popular public figures in the world, her death brought a massive outpouring of grief. Mourners began leaving bouquets of flowers at Kensington Palace immediately. The piles of flowers reached about 30 feet from the palace gate. As in her life, her death demanded the attention of the world. She was so loved, and many felt, so mistreated during her marriage. Following her funeral on September 6, 1997, an event that was watched by 2.5 billion people, she was laid to rest on an island at Althorp Estate, which is her childhood home, and is which is where her brother, Earl Charles Spencer lives to this day. The island is off limits, but the estate is open to the public during July and August each year.

Diana was survived by her two sons, Prince William, who was 15 at the time, and Prince Harry, who was 12. Today she has two daughters-in-law, Duchess Catherine and Duchess Meaghan, as well as five grandchildren, Prince George, Princess Charlotte, Prince Louis; as well as; Archie and Lillibet. Today marks 25 years since the passing of Princess Diana. Gone but not forgotten.

Diana was survived by her two sons, Prince William, who was 15 at the time, and Prince Harry, who was 12. Today she has two daughters-in-law, Duchess Catherine and Duchess Meaghan, as well as five grandchildren, Prince George, Princess Charlotte, Prince Louis; as well as; Archie and Lillibet. Today marks 25 years since the passing of Princess Diana. Gone but not forgotten.

These days, we have probably seen more “shortages” of the staples needed for daily life than ever before. Things like food, water, toilet paper, sugar, gasoline, and so many other things that most people use every day, are suddenly missing from our shelves or stations. Today’s “shortages” are mostly caused by forced blocking of shipping channels, and other political maneuvering…at least these days. There are as many reasons for most shortages as there are shortages, in reality, but some shortages have been stranger over the years than others. Sometimes, it’s even for our own good or if it is “perceived” to be for our own good.

These days, we have probably seen more “shortages” of the staples needed for daily life than ever before. Things like food, water, toilet paper, sugar, gasoline, and so many other things that most people use every day, are suddenly missing from our shelves or stations. Today’s “shortages” are mostly caused by forced blocking of shipping channels, and other political maneuvering…at least these days. There are as many reasons for most shortages as there are shortages, in reality, but some shortages have been stranger over the years than others. Sometimes, it’s even for our own good or if it is “perceived” to be for our own good.

Things have been pulled off the shelves because of recalls, like vegetables that may have Salmonella, and even if the source was confined to one small area of one plant, as was the case with baby formula. The government shut down all the plants, causing a serous baby formula shortage. No one wants to buy unsafe formula, but that was really never the case, and they knew it. Excedrin was pulled off the shelves because it “might” have an ingredient that was unsafe, and then weeks later, it was back, in exactly the same formulation.

The closing of a business is one of the biggest reasons for items to suddenly be missing from the shelves.

Twinkies is a prime example. When Hostess Brands Inc, the maker of Twinkies and other cherished American treats, announced bankruptcy and closure in 2012, consumers made a mad rush to their local supermarkets to get their hands on the cream-filled pastries before they were gone for good. It is that act that prompted the myth that Twinkies have an unlimited shelf life. The snacks were back on the shelves by summer, when Hostess and all of its brand holdings, including Twinkies, were purchased out of bankruptcy by the private equity firms Apollo Global Management and Metropoulos and Company in 2013.

Twinkies is a prime example. When Hostess Brands Inc, the maker of Twinkies and other cherished American treats, announced bankruptcy and closure in 2012, consumers made a mad rush to their local supermarkets to get their hands on the cream-filled pastries before they were gone for good. It is that act that prompted the myth that Twinkies have an unlimited shelf life. The snacks were back on the shelves by summer, when Hostess and all of its brand holdings, including Twinkies, were purchased out of bankruptcy by the private equity firms Apollo Global Management and Metropoulos and Company in 2013.

One of the funniest shortages, though not funny at the time or in the repeat of it in recent times, was the 1973 toilet paper shortage. It happened as the result of a joke by Johnny Carson. He said, “You know, we’ve got all sorts of shortages these days. But have you heard the latest? I’m not kidding. I saw it in the papers. There’s an acute shortage of toilet paper.” The remarks that were meant as a joke, caused people to rush to the stores and buyout all the toilet paper. To make matters worse, some stores began rationing. Finally, Carson took to the airwaves to apologize, saying, “I don’t want to be remembered as the man who created a false toilet paper scare. I just picked up the item from the paper and enlarged it somewhat…there is no shortage.”

There are so many ways a shortage can get started. Some are real events, while others are manufactured. While some are not exactly detrimental, as was the case with Twinkies, some can cause serious harm and even death…even many deaths. Some shortages cannot be helped, but those that can, in all prudence, should be avoided at all costs.

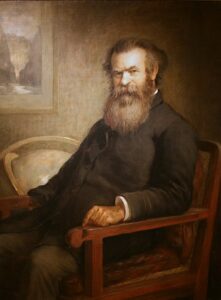

John Wesley Powell was an American geologist, US Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. As if that accreditation wasn’t enough, Powell was most famous leading an 1869 geographic expedition. The expedition was a three-month river trip down the Green and Colorado rivers, which included the first official US government-sponsored passage through the Grand Canyon. While it was successful, the expedition was not without issue. During the trip, three men became convinced that they would have a better chance surviving the desert than the raging rapids that lay ahead of them. So, a bit of a mutiny ensued, in which the three men left Powell’s expedition through the Grand Canyon and decide to scale the cliffs to the plateau above.

John Wesley Powell was an American geologist, US Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. As if that accreditation wasn’t enough, Powell was most famous leading an 1869 geographic expedition. The expedition was a three-month river trip down the Green and Colorado rivers, which included the first official US government-sponsored passage through the Grand Canyon. While it was successful, the expedition was not without issue. During the trip, three men became convinced that they would have a better chance surviving the desert than the raging rapids that lay ahead of them. So, a bit of a mutiny ensued, in which the three men left Powell’s expedition through the Grand Canyon and decide to scale the cliffs to the plateau above.

As with many mutinies, the men quickly found out that they didn’t necessarily know as much as they thought. In fact, theirs was a serious mistake. Still, their fears were not totally unfounded. The men feared that the plan to float the brutal rapids was suicidal. To make matters worse, Powell was a one-armed Civil War veteran and self-trained naturalist. One arm and those rapids could prove catastrophic. Powell was, however, accompanied by 11 men, which could have helped, but they were in four wooden boats, meaning that all hands were needed. Powell was fearless, and he led the expedition through the Grand Canyon and over punishing rapids that many would hesitate to run even with modern rafts.

For the group, the worst was yet to come. Near the lower end of the canyon, the party heard the roar of giant rapids. They decided to explore the situation further, before they took that plunge. The party moved to shore, and then walked down river to explore the river first. The men saw was could only be referred to as “the worst rapids yet” and Powell agreed, writing that, “The billows are huge, and I fear our boats could not ride them…There is discontent in the camp tonight and I fear some of the party will take to the mountains but hope not.”

Overnight, the fears grew, and the next day, three of his men left to take their chances in the desert above, because they were sure that the rapids an impossible barrier for the boats. So, on August 28, 1869, Seneca Howland, O G Howland, and William H Dunn said goodbye to Powell and the other men and began the long climb up out of the Grand Canyon. The rest of the party mustered their courage, climbed into the boats, and  pushed off into the wild rapids.

pushed off into the wild rapids.

Amazingly, all of the river crew survived, and the expedition emerged from the canyon the next day. The three men who left the group were not so fortunate. Upon reaching the nearest settlement, Powell learned that the three men who left the group, had encountered a war party of Shivwit Indians and were killed. While the killings overshadowed the excitement of the successful expedition, the next expedition through the Grand Canyon in 1871, was much better funded than had been the first. I suppose knowing that it can be done, made it easier to donate to the second trip.

Most people today wouldn’t remember a 1920s show called “Our Gang” unless they happen to be an old black and white movie buff. The show was about a “gang” of young kids, and all the mischief they got into. Of course, they weren’t bad kids, just adventurous kids. One of those kids was Robert E “Bobby” Hutchins, who was born on March 29, 1925, to James and Olga (Constance) Hutchins in Tacoma, Washington. His father was a native of Kentucky and his mother a native of Washington. Young Hutchins was a popular child actor who played “Wheezer” in the “Our Gang” movies. His short movie career began in 1927, when he was just 2 years old. He was only eight

Most people today wouldn’t remember a 1920s show called “Our Gang” unless they happen to be an old black and white movie buff. The show was about a “gang” of young kids, and all the mischief they got into. Of course, they weren’t bad kids, just adventurous kids. One of those kids was Robert E “Bobby” Hutchins, who was born on March 29, 1925, to James and Olga (Constance) Hutchins in Tacoma, Washington. His father was a native of Kentucky and his mother a native of Washington. Young Hutchins was a popular child actor who played “Wheezer” in the “Our Gang” movies. His short movie career began in 1927, when he was just 2 years old. He was only eight  when he left the series in 1933. Hutchins was given the nickname of “Wheezer” after running around the studios on his first day so much that he began to wheeze. The nickname fit him so well that it was incorporated into the show. Wheezer appeared in 58 “Our Gang” films during his six years in the series. For much of his run, “Wheezer” was portrayed as the tag-along little brother, put off by the older children but always eager to be part of the action.

when he left the series in 1933. Hutchins was given the nickname of “Wheezer” after running around the studios on his first day so much that he began to wheeze. The nickname fit him so well that it was incorporated into the show. Wheezer appeared in 58 “Our Gang” films during his six years in the series. For much of his run, “Wheezer” was portrayed as the tag-along little brother, put off by the older children but always eager to be part of the action.

As would always be the case with a show like “Our Gang,” Hutchins eventually outgrew the series, so he and his family moved back to Tacoma, where he  entered public school. After he graduated from high school, he joined the US Army Air Forces in 1943, enrolling in the Aviation Cadet Program with the goal of becoming a pilot. Hutchins was killed in a mid-air collision on May 17, 1945, while trying to land a North American AT-6D-NT Texan, serial number 42-86536, of the 3026th Base Unit, during a training exercise. Hutchins’ plane struck an AT-6C-15-NT Texan, 42-49068, of the same unit at Merced Army Air Field in Merced, California…later known as Castle Air Force Base. The other pilot, Edward F Hamel, survived the crash. Hutchins’ mother, Olga Hutchins, had been scheduled to travel to the airfield for his graduation from flying school, which would have occurred the week after he died. He is buried in the Parkland Lutheran Cemetery in Tacoma, Washington. When you see him acting the “Our Gang” movies, it’s really sad to think that his life would be cut short at the age of just 20 years. Nevertheless, he was doing what he really wanted to do, and serving his country in the process.

entered public school. After he graduated from high school, he joined the US Army Air Forces in 1943, enrolling in the Aviation Cadet Program with the goal of becoming a pilot. Hutchins was killed in a mid-air collision on May 17, 1945, while trying to land a North American AT-6D-NT Texan, serial number 42-86536, of the 3026th Base Unit, during a training exercise. Hutchins’ plane struck an AT-6C-15-NT Texan, 42-49068, of the same unit at Merced Army Air Field in Merced, California…later known as Castle Air Force Base. The other pilot, Edward F Hamel, survived the crash. Hutchins’ mother, Olga Hutchins, had been scheduled to travel to the airfield for his graduation from flying school, which would have occurred the week after he died. He is buried in the Parkland Lutheran Cemetery in Tacoma, Washington. When you see him acting the “Our Gang” movies, it’s really sad to think that his life would be cut short at the age of just 20 years. Nevertheless, he was doing what he really wanted to do, and serving his country in the process.

When we think of structures that have stood the test of time, we think of stone structures or structures made out of hard woods that are able to weather the elements, but sometimes a structure defies the normal expectations, as stands the test of time against all odds. There is a house in the ghost town of Rhyolite, Nevada that is the perfect example of that kind of structure.

When we think of structures that have stood the test of time, we think of stone structures or structures made out of hard woods that are able to weather the elements, but sometimes a structure defies the normal expectations, as stands the test of time against all odds. There is a house in the ghost town of Rhyolite, Nevada that is the perfect example of that kind of structure.

A local saloon owner named Tom Kelly decided to build a house in 1906. Unfortunately, lumber was scarce in the area at the time, so the innovative 76-year-old saloon owner decided to use the materials at hand to build his house…bottles. Not many people would have come up with such an idea, much less have the ability to carry out the strange design and actually make it a house. An estimated 50,000 beer, whiskey, soda, and medicine bottles were used to build the structure, and amazingly, it is still standing today. Tom Kelley was 76 years old when he built the house that took him almost six months to complete. Thankfully he didn’t have to drink all the alcohol in those 50,000 bottles. The bottle house also sports a “garden” of sculptures made of broken glass  including miniature houses, bottle ropes, and a host of other “glass treasures” that would probably qualify as junk to most of us, but they seem to fit the bottle house perfectly.

including miniature houses, bottle ropes, and a host of other “glass treasures” that would probably qualify as junk to most of us, but they seem to fit the bottle house perfectly.

There was a period of time when the house was in some disrepair, but amazingly it was things like needing a new roof that caused the disrepair, not broken bottles in the structure. In 1925, Paramount Pictures wanted to use the house in a movie, so as part of the deal, they restored and re-roofed the house. The house, which really is pretty cute, was given to the Beatty Improvement Association for maintenance as a historical site. That might be part of why it still stands today, but the work that went into it originally was a big part of the house’s ability to stand the test of time.

Louis J Murphy leased and maintained the house as a museum that he ran with a woman named Bessie Stratton Moffat until he died in 1956. Later, a man named Tommy Thompson and his wife lived in the house, while maintaining a museum and a relic shop. How unique it must have been to live in such a house. No, it’s not a big house, and probably doesn’t have a monetary value that would rival today’s market, but its value really lies in a different area. The house fit the Thompsons, however. Tommy was a musician, who worked

playing the accordion in the saloons in Rhyolite back when it was a boomtown. Evan Thompson maintained the house for a while after his parents died. He is the last person to actually live in the house, but he finally moved on, living in Pioneer, Nevada now. Once again, the bottle house stands empty, no longer in use, but still as resilient as ever.

playing the accordion in the saloons in Rhyolite back when it was a boomtown. Evan Thompson maintained the house for a while after his parents died. He is the last person to actually live in the house, but he finally moved on, living in Pioneer, Nevada now. Once again, the bottle house stands empty, no longer in use, but still as resilient as ever.

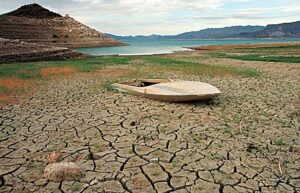

As a kid, I remember going to the Grand Canyon, Las Vegas, and Lake Mead. I particularly enjoyed Lake Mead, because the water was warm, unlike most lakes. At the time, and for many years afterward, I really didn’t know much about the lake, its origins, or its secrets. These days, I maybe know too much about its secrets. In fact, some of them are really creepy. Many lakes sport hidden ghost towns, underground ranches, and various sunken boats. There are probably more bodies in them that we know or want to think about too, but when a drought occurs and we find ourselves hearing about body after body being found in a lake that is close to one of the big mob-controlled areas of the nation, it makes you wonder exactly what happened here and just how many more bodies will surface. Well, in the case of Lake Mead, the answer is a total of five bodies…so far. Who knows how many more will surface.

As a kid, I remember going to the Grand Canyon, Las Vegas, and Lake Mead. I particularly enjoyed Lake Mead, because the water was warm, unlike most lakes. At the time, and for many years afterward, I really didn’t know much about the lake, its origins, or its secrets. These days, I maybe know too much about its secrets. In fact, some of them are really creepy. Many lakes sport hidden ghost towns, underground ranches, and various sunken boats. There are probably more bodies in them that we know or want to think about too, but when a drought occurs and we find ourselves hearing about body after body being found in a lake that is close to one of the big mob-controlled areas of the nation, it makes you wonder exactly what happened here and just how many more bodies will surface. Well, in the case of Lake Mead, the answer is a total of five bodies…so far. Who knows how many more will surface.

One body was found in a barrel, with a gun nearby, causing speculation of a mob killing, and possibly making people who might have been the perpetrators of mob murders…if they are still alive, to become a little nervous about their crimes being found out. Of course, the police aren’t telling us much, but it is said that the body in the barrel, discovered in May, had been shot in the head and after being stuffed in the barrel it was thrown overboard, in the hope that it would never be seen again. It was the type of killing that was classic mob style, or so we’ve been told in the movies. Las Vegas was, and maybe still is, a big mob crime city, and this type of killing was a trademark in the 1970s and 19802. So, it is entirely possible that the killer is still alive and could be brought to justice.

Shortly after the body in the barrel was found, another body surfaced, and then in July a third body was found. Days after the body in the barrel surfaced, another corpse was reported. A third was discovered in July. Now, the skeletal remains of two more people were found just this month in the Swim Beach area. It makes me

wonder how many more bodies will surface, if the drought continues and the lake level continues to drop. The lake level has dropped nearly 200 feet due to two decades of drought. Right now, the lake is very close to the level it was when it was originally filled after the building of Hoover Dam. I guess the old saying about the truth finding you out is true. the bodies, some long hidden, are coming out to tell of their demise.

wonder how many more bodies will surface, if the drought continues and the lake level continues to drop. The lake level has dropped nearly 200 feet due to two decades of drought. Right now, the lake is very close to the level it was when it was originally filled after the building of Hoover Dam. I guess the old saying about the truth finding you out is true. the bodies, some long hidden, are coming out to tell of their demise.

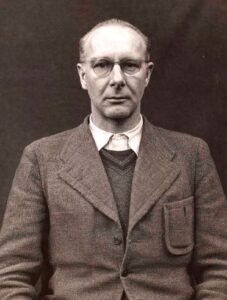

Until August 18, 1941, Adolf Hitler had been systematically murdering the mentally ill and developmentally disabled people in Germany, but word was getting out, and the “good” people of Germany were understandably outraged by such an evil practice. The people began protesting, and in an effort to avoid rioting, Hitler announced on this day in 1941, that the practice would cease. I’m sure the people were glad, and they most likely thought they had won this battle, but as we all know, Adolf Hitler is a man who lies…in fact it was all lies!!

Until August 18, 1941, Adolf Hitler had been systematically murdering the mentally ill and developmentally disabled people in Germany, but word was getting out, and the “good” people of Germany were understandably outraged by such an evil practice. The people began protesting, and in an effort to avoid rioting, Hitler announced on this day in 1941, that the practice would cease. I’m sure the people were glad, and they most likely thought they had won this battle, but as we all know, Adolf Hitler is a man who lies…in fact it was all lies!!

The killing began in 1939, when head of Hitler’s Euthanasia Department, Dr Viktor Brack oversaw the creation of the T.4 program. At first, the program began systematically killing of children deemed “mentally defective.” Children were transported from all over Germany to a Special Psychiatric Youth Department, after being told that the children were going to be treated there, but they were killed instead. Parents were told that their children had become ill, and simply died. Later, because of Hitler’s hatred mainly for Jewish people, certain criteria were established for non-Jewish children. Even if they “qualified” to be killed because of their mental issues, they had to be “certified” mentally ill, schizophrenic, or incapable of working for one reason or another before they could be killed. Jewish children already in mental hospitals, whatever the reason or whatever the prognosis, were automatically to be subject to the program and killed. The victims were either injected with lethal substances or were led to “showers” where the children sat as gas flooded the room through water pipes. Later the program was expanded to include adults.

As this practice continued, the people started getting angry, and before long protests began mounting within Germany, especially by doctors and pastors. A few of these people even had the courage to write Hitler directly and describe the T.4 program as “barbaric” but others circulated their opinions more discreetly. Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and the man who would direct the systematic extermination of European Jewry, had only one regret: that the SS had not been put in charge of the whole affair. “We know how to deal with it correctly, without causing useless uproar among the people.”

In 1941, when Bishop Count Clemens von Galen denounced the euthanasia program from his pulpit, Hitler decided that he did not need such publicity. He ordered the program suspended but didn’t tell the German people that the suspension was only to be in Germany. Still, even though it was suspended in Germany, 50,000

people had already fallen victim to the hideous program. Then came the “other shoe dropping” as the practice was picked up in earnest in occupied Poland. Hitler was a liar, and he was evil. He assumed that the people of the world were stupid, and he could hide his horrific practice from them. Stopping the practice in the name of humane practices…not!! Lies!! All of it!!

people had already fallen victim to the hideous program. Then came the “other shoe dropping” as the practice was picked up in earnest in occupied Poland. Hitler was a liar, and he was evil. He assumed that the people of the world were stupid, and he could hide his horrific practice from them. Stopping the practice in the name of humane practices…not!! Lies!! All of it!!