History

Mildred Fish was an American-German literary historian, translator, and later, a German Resistance fighter in Nazi Germany. They fell in love and married, moving to Germany right after. She met her future husband, Arvid Harnack in 1926. Arvid was a grad student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. In Germany, Mildred worked in education and Arvid secured a position with the Reich Economic Ministry. Throughout the 1930s, Mildred and Arvid, became increasingly alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power. They could see that he had ulterior

Mildred Fish was an American-German literary historian, translator, and later, a German Resistance fighter in Nazi Germany. They fell in love and married, moving to Germany right after. She met her future husband, Arvid Harnack in 1926. Arvid was a grad student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. In Germany, Mildred worked in education and Arvid secured a position with the Reich Economic Ministry. Throughout the 1930s, Mildred and Arvid, became increasingly alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power. They could see that he had ulterior  motives. They communicated with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe.

motives. They communicated with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe.

When Mildred came to the United States for a lecture tour in 1937, her family begged her to relocate permanently, but she refused and resumed her life in Germany. I suppose she thought she could be of better assistance there than in the United States. When war was declared in 1941, she did not leave with other Americans.  They couldn’t leave, because by then, Mildred and Arvid were involved with a communist espionage network known by the Gestapo as “The Red Orchestra”. The ring, which provided important intelligence to the USSR, was compromised and the members were arrested. I’m sure they knew this was a death sentence for them.

They couldn’t leave, because by then, Mildred and Arvid were involved with a communist espionage network known by the Gestapo as “The Red Orchestra”. The ring, which provided important intelligence to the USSR, was compromised and the members were arrested. I’m sure they knew this was a death sentence for them.

After they were tried as traitors, Arvid was sentenced to death and executed on December 22, 1942. Mildred was given a six year sentence, but Hitler refused to endorse her punishment. As only a dictator can, he insisted on a retrial, after which she was condemned on January 16, 1943. She was beheaded by guillotine at Plotzensee Prison on February 16, 1943. She was the only American female executed on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Because of her connection to possible communist sympathies and post-war McCarthyism, her story is virtually unknown in the United States.

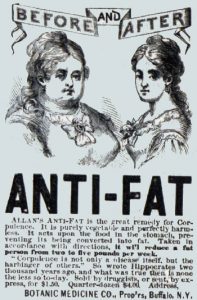

Every year, as the new year approaches, we take a look at our life and try to think of how we could improve ourselves. Many of us decide that it is time to start a new diet. Every year some new diet shows up. Some people will find something that works for them in the long term, but the reality is that just as often, the new diet doesn’t work, and they set out in search of the next new thing. The reality is that no one diet works for everyone, and dieters sometimes have to try several to see what works for them. It is a fact that has irritated every one of us for years.

Every year, as the new year approaches, we take a look at our life and try to think of how we could improve ourselves. Many of us decide that it is time to start a new diet. Every year some new diet shows up. Some people will find something that works for them in the long term, but the reality is that just as often, the new diet doesn’t work, and they set out in search of the next new thing. The reality is that no one diet works for everyone, and dieters sometimes have to try several to see what works for them. It is a fact that has irritated every one of us for years.

Most people on a diet know that one of the first things to go is the sugar, join a gym, and stubbornly stick to our plan. What we don’t realize is that diets are not a new  thing. As early as the 18th century, diet doctors began to recommend strict, low fat meals, and newspapers featured adverts for tonic and diet pills. Who would have thought. The idea of beauty changes, and it had changed to a much more slender look.

thing. As early as the 18th century, diet doctors began to recommend strict, low fat meals, and newspapers featured adverts for tonic and diet pills. Who would have thought. The idea of beauty changes, and it had changed to a much more slender look.

Suddenly, attitudes towards over-indulgence, obesity, and body shape were hotly debated, and there developed a pressure to demonstrate self-restraint. Of course, the debates were also about what was a healthy way to eat, and what wasn’t. That debate continues to this day. At one point, a doctor lost weight by cutting fat, and the low-fat craze began. Many people would say that low-fat should not be a craze, but a standard. I won’t “weigh” in on that debate, because we all have our own ideas. Since that time, we have all tried a multitude of diets in an attempt to reach our perfect selves. We can say that some of the new body images would be healthier, and we would be right. Too skinny isn’t healthy, nor is too fat. The argument on that will continue, just as it started in the 18th century…a debate in progress.

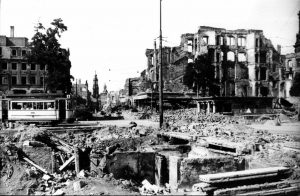

The American prisoners of war had heard the Allied planes pass overhead many times before, but this was different. Along with the sound of the planes, came the howling of Dresden’s air raid sirens. Dresden was known as the “Florence of the Elbe.” The American prisoners of war were moved two stories below into a meat locker. I don’t really understand that in light of the outcome. The Germans didn’t care about their prisoners, but I guess they didn’t care about their own countrymen either. Why would they move their prisoners to a place of safety, but leave the people of the town to fend for themselves. I suppose that they might have wanted the prisoners for leverage, but how good is a victory, if there are no one to live in the town.

The American prisoners of war had heard the Allied planes pass overhead many times before, but this was different. Along with the sound of the planes, came the howling of Dresden’s air raid sirens. Dresden was known as the “Florence of the Elbe.” The American prisoners of war were moved two stories below into a meat locker. I don’t really understand that in light of the outcome. The Germans didn’t care about their prisoners, but I guess they didn’t care about their own countrymen either. Why would they move their prisoners to a place of safety, but leave the people of the town to fend for themselves. I suppose that they might have wanted the prisoners for leverage, but how good is a victory, if there are no one to live in the town.

In this instance, I suppose it didn’t matter, because when the prisoners were brought back to the surface, “the city was gone”…levelled by the bombs from the RAF and the USAAF. One prisoner, Kurt Vonnegut who was a writer and social critic, recalled the scene…shocked. The devastation was unbelievable, the bombing had reduced the “Florence of the Elbe” to rubble and flames. Still, Vonnegut could not help but be thankful that he was still alive. Who wouldn’t be thankful. He was alive, and he would be forever thankful. Who wouldn’t be. It was a second chance.

The devastating, three-day Allied bombing attack on Dresden from February 13 to 15, 1945 in the final months of World War II became one of the most controversial Allied actions of the war. Some 2,700 tons of explosives and incendiaries were dropped by 800-bomber raid and decimated the German city.

Dresden was a major center for Nazi Germany’s rail and road network. The plan was to destroy the city, and thereby overwhelm German authorities and services, and clog all transportation routes with hordes of refugees. An estimated 22,700 to 25,000 people were killed, in the attacks. Normally, Dresden had 550,000 citizens, but at the time there were approximately 600,000 refugees too. The Nazis tried to say that 550,000 had been killed, but that number was quickly proven wrong.

The Allied assault came a less than a month after 19,000 US troops were killed in Germany’s last-ditch offensive at the Battle of the Bulge, and three weeks after the grim discovery of the atrocities committed by Nazi forces at Auschwitz. In an effort to force a surrender, the Dresden bombing was intended to terrorize the civilian population locally and nationwide. It certainly had that effect in 1945.

Scientists have done much for mankind. They are dedicated to finding a solution, a cure, a way, often sacrificing their own time, family life, and sometimes even their own life, to solve a problem, find a cure, or make things better. It seems a strange thing to give one’s life for an experiment, and yet people have done just that.

Scientists have done much for mankind. They are dedicated to finding a solution, a cure, a way, often sacrificing their own time, family life, and sometimes even their own life, to solve a problem, find a cure, or make things better. It seems a strange thing to give one’s life for an experiment, and yet people have done just that.

Marie Curie conducted pioneering research on radioactivity, and the discovery of two elements, polonium and radium. Unfortunately, she would die of aplastic anemia, a disease of the bone marrow that was very likely caused by the radioactivity she had been exposed for so many years.

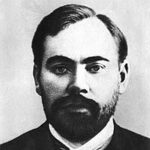

Alexander Bogdanov was obsessed with Hematology. Bogdanov did research in blood transfusions in the 1920s. In fact, he gave himself blood transfusions…over and over. He insisted that the transfusions made him feel better. Maybe they did, but they would also be his undoing, when he transfused himself with the blood of a student who had malaria. Bogdanov contracted the disease and died.

Many people have heard of David Johnston who was a volcanologist. He wanted to see Mount Saint Helens for himself. He was the first to report and urge the evacuation, but seeing the show cost him his life too. He was killed by the Pyroclastic Blast.

Probably one of the most awful deaths to me was that of Harold Maxwell-Lefroy. He spent a lot of time studying bugs, or rather how to get rid of them. He knew that something needed to be done to get rid of these pests. He

was very good at his work, but unfortunately, the chemicals would kill people too, and he inhaled enough to do so. In his lab, he inhaled a lethal amount of Lewisite.

was very good at his work, but unfortunately, the chemicals would kill people too, and he inhaled enough to do so. In his lab, he inhaled a lethal amount of Lewisite.

There are others, maybe more that anyone knows of. If they weren’t famous or successful, their deaths might have looked like accidents, diseases, accidental overdoses, or even suicide, when in fact they were nothing of the kind. They are just some of the great scientific minds who gave their all in the name of science. Sadly, by accident.

When we think of space, we picture things floating slowly and peacefully along…or at least I do, but the reality is that most things in space are moving quite fast, and along a specific trajectory. While it seems quite chaotic when you think about all the things that are floating around out there, for the most part, it all moves along in a completely organized manner…for the most part.

When we think of space, we picture things floating slowly and peacefully along…or at least I do, but the reality is that most things in space are moving quite fast, and along a specific trajectory. While it seems quite chaotic when you think about all the things that are floating around out there, for the most part, it all moves along in a completely organized manner…for the most part.

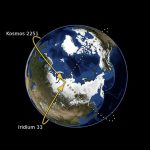

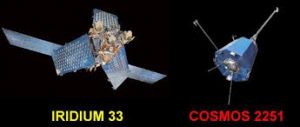

For things in space to change course, there must be something that interferes with the trajectory…a planet that gets in the way, a new piece of space junk that crosses its path, or a satellite that is falling out of orbit. Even with as much “stuff” as exists in space, these are not common occurrences…or at least not as common as you might think. Nevertheless, on February 10, 2009, two communications satellites…the active commercial Iridium 33 and the derelict Russian military Kosmos-2251…accidentally collided at a speed of 26,000 miles per hour and an altitude of 490 miles above the Taymyr Peninsula in Siberia. That speed puts the collision in the hypervelocity category…in fact, very much so. Hypervelocity is very high velocity, listed as 6,700 miles per hour, or more. At 26,000 miles per hour, this collision more than qualified. That kind of speed is shocking…at least in my mind, and the collision must have been horrific. While there had been other collisions in space, this was the first time a hypervelocity collision occurred between two satellites. Prior to that, all accidental hypervelocity collisions had involved a satellite and a piece of space debris.

The collision occurred at 16:56 UTC, which is the time standard commonly used across the world. The world’s timing centers have agreed to keep their time scales closely synchronized, therefore the name Coordinated Universal Time. The collision destroyed both the Iridium 33 and Kosmos-2251. The Iridium satellite was operational at the time of the collision. Kosmos-2251 had gone out of service in 1995. Kosmos-2251 had no propulsion system, and was no longer actively controlled. Had it been actively controlled, they might have guided it out of harm’s way. NASA initially estimated the debris at 1,000 pieces larger than 3.9, and many smaller pieces, but in reality the US Space Surveillance Network had cataloged 2,000 large pieces by July 2011. They thought the International Space Station, which orbits at about 270 miles below the collision course, was safe, but one piece came within 130 yards at one time, making for a tense few hours.

In the days following the first reports of the incident in 2009, a number of reports of phenomena in the US states of Texas, Kentucky, and New Mexico were attributed to debris from the collision. NASA and the United States Strategic Command, which tracks satellites and orbital debris, did not announce that any debris had  entered the atmosphere at the time and reported that these phenomena were unrelated to the collision. Still, things like sonic booms heard by witnesses in Kentucky, on February 13, 2009 made no sense in any other scenario. Then, the National Weather Service issued an information statement alerting residents of sonic booms due to the falling satellite debris. The Federal Aviation Administration also released a notice warning pilots of the re-entering debris. However, some reports include details that point to these phenomena being caused by a meteoroid shower rather than debris. A very bright meteor over Texas on February 15, 2009, was mistaken for re-entering debris. By December 2011, many pieces of the debris were in an observable orbital decay, moving towards Earth, and were expected to burn up in the atmosphere within one to two years. By January 2014, 24% of the known debris orbits had actually decayed. In 2016, Space News listed the collision as the second biggest fragmentation event in history, with Kosmos-2251 and Iridium 33 producing respectively 1,668 and 628 pieces of cataloged debris, of which 1,141 and 364 pieces of tracked debris remain in orbit as of January 2016.

entered the atmosphere at the time and reported that these phenomena were unrelated to the collision. Still, things like sonic booms heard by witnesses in Kentucky, on February 13, 2009 made no sense in any other scenario. Then, the National Weather Service issued an information statement alerting residents of sonic booms due to the falling satellite debris. The Federal Aviation Administration also released a notice warning pilots of the re-entering debris. However, some reports include details that point to these phenomena being caused by a meteoroid shower rather than debris. A very bright meteor over Texas on February 15, 2009, was mistaken for re-entering debris. By December 2011, many pieces of the debris were in an observable orbital decay, moving towards Earth, and were expected to burn up in the atmosphere within one to two years. By January 2014, 24% of the known debris orbits had actually decayed. In 2016, Space News listed the collision as the second biggest fragmentation event in history, with Kosmos-2251 and Iridium 33 producing respectively 1,668 and 628 pieces of cataloged debris, of which 1,141 and 364 pieces of tracked debris remain in orbit as of January 2016.

Contrary to what was expected, a small piece of Kosmos-2251 satellite debris safely passed by the International Space Station at 2:38 am EDT, Saturday, March 24, 2012, at a distance of just 130 yards. As a precaution, ISS management had the six crew members on board the orbiting complex take refuge inside the two docked Soyuz rendezvous spacecraft until the debris had passed. It was a tense time…not knowing if the debris would hit them or miss them. It is not unusual to see two satellites approach within several miles of each other. In fact, these events occur numerous times each day. It’s a challenge to sort through the large number of potential collisions to identify those that are of higher risk. Precise, up-to-date information regarding current satellite positions is difficult to obtain. In fact, the calculations made by CelesTrak had expected these two satellites to miss by 1,916 feet…not a huge distance, but had it been right, it would have been enough.

Planning an avoidance maneuver with due consideration of the risk, the fuel consumption required for the maneuver, and its effects on the satellite’s normal functioning can also be challenging. John Campbell of Iridium spoke at a June 2007 forum discussing these tradeoffs and the difficulty of handling all the notifications they were getting regarding close approaches, which numbered 400 per week for approaches within three miles for  the entire Iridium constellation. He estimated the risk of collision per conjunction as one in 50 million…oops!! That was just a little bit off.

the entire Iridium constellation. He estimated the risk of collision per conjunction as one in 50 million…oops!! That was just a little bit off.

This collision and numerous near-misses have renewed calls for mandatory disposal of defunct satellites by deorbiting them, or at the very least, sending them to a graveyard orbit, but no such international law exists at this time. Nevertheless, some countries have adopted such a law domestically, such as France in December 2010. The United States Federal Communications Commission requires all geostationary satellites launched after March 18, 2002, to commit to moving to a graveyard orbit at the end of their operational life. It’s a start.

Just imagine living in a place where owning or even borrowing a book could get you, and anyone who gave you a book, killed. During the Holocaust, the Jews and other nationalities and religious groups who didn’t fit in with the Aryan race, were considered non-people, and therefore expendable. They were not allowed to live like normal people. They were considered “expendable.” Their lives were not worth the trouble it took to care for them, even their fiends and neighbors were expected to turn them over to be deported to the ghettos and even killed. They were often powerless to help themselves. Still, most of them never lost hope. When the Nazis began to occupy Czechoslovakia in 1939, the persecution of the Jews began almost immediately. Things were hard for everyone, but the children were often in more peril than anyone else. Many were to young to work and that made them even less “important” to the Nazis. To make matters worse, they were often separated from their parents…everything they knew was stripped from them.

Just imagine living in a place where owning or even borrowing a book could get you, and anyone who gave you a book, killed. During the Holocaust, the Jews and other nationalities and religious groups who didn’t fit in with the Aryan race, were considered non-people, and therefore expendable. They were not allowed to live like normal people. They were considered “expendable.” Their lives were not worth the trouble it took to care for them, even their fiends and neighbors were expected to turn them over to be deported to the ghettos and even killed. They were often powerless to help themselves. Still, most of them never lost hope. When the Nazis began to occupy Czechoslovakia in 1939, the persecution of the Jews began almost immediately. Things were hard for everyone, but the children were often in more peril than anyone else. Many were to young to work and that made them even less “important” to the Nazis. To make matters worse, they were often separated from their parents…everything they knew was stripped from them.

In 1942, when a girl named Dita Polachova was 13 years old, she and her parents were deported to Ghetto Theresienstadt life got even worse than it was before. Later they were sent to Auschwitz, where Dita’s father died. She and her mother were sent to forced labor in Germany and finally to a concentration camp called Bergen-Belsen. Dita’s mother died at Bergen-Belsen. Even in the face of so much sadness in her life, Dita never gave up. She risked her own life to protect a selection of eight books smuggled in by prisoners of Auschwitz. She stored the books in hidden pockets in her smock, and circulated them to the hundreds of children imprisoned in Block 31. Books were forbidden for the prisoners in the camps. The Nazis didn’t want them to have any knowledge of the outside world, or access to any kind of education materials or any books. The Nazis believed that none of these people were going to survive their stay in the camps anyway, so they didn’t need to do anything but work and die.

The prisoners had different ideas. Within the walls, there was a family camp known as BIIb. It was a place where the children could play and sing, but school was prohibited. Nevertheless, the Nazis were not able to enforce their will on the people. In spite of the orders of the Nazis, Fredy Hirsch established a small, yet influential school to house the children while their parents slaved in the camp. The materials were the biggest problem. The books, had to be hidden from the Nazi guards at all costs. Hirsch selected Dita, a brave and independent young woman from Prague to take over as the new Librarian of Auschwitz in January of 1944. Dita was a brave girl, who took her responsibility seriously.

While her parents are trying to stay alive in Auschwitz, Dita was fighting her own battle to preserve the books that bring joy to the children in the camp. The books are one of the few things that allow the children to escape from the walls in which they are surrounded, even if just for a moment. As the war progresses, Dita continues to diligently serve the teachers and children of Block 31. Then, Dita’s situation grew much worse. Her father passed away in the camp due to pneumonia. Dita and her mother are left alone to fight the battle on their own. Dita’s mother is grew weaker with age, and Dita knew she had to assume more responsibility. Dita is aware of the fact that the camp is simply a front to produce Nazi propaganda. She began to fight despair, as she struggles to feel the value in her life. By March 1944, the feeling of hopelessness grows. The Nazis announce that the inmates who arrived in September will be transferred to another division, which is really code for  murder. The BIIb continued until they heard that the Nazis are going to liquidate the family camp and separate the fit to work from the rest. Dita’s mother Liesl, was grown old and very weak by now. She was able to sneak into the group that is fit to work along with her daughter, narrowly. They were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Just when Dita gets to the point where she feels this might be the end, the Allied forces liberate the camp, but it is too late for Dita’s mother, who died just after the English arrived. Dita is now free, but it has been at great cost…the kind most of us cannot begin to comprehend. Dita later met and married Otto Kraus, an author, and they settled in Israel where they were both teachers.

murder. The BIIb continued until they heard that the Nazis are going to liquidate the family camp and separate the fit to work from the rest. Dita’s mother Liesl, was grown old and very weak by now. She was able to sneak into the group that is fit to work along with her daughter, narrowly. They were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Just when Dita gets to the point where she feels this might be the end, the Allied forces liberate the camp, but it is too late for Dita’s mother, who died just after the English arrived. Dita is now free, but it has been at great cost…the kind most of us cannot begin to comprehend. Dita later met and married Otto Kraus, an author, and they settled in Israel where they were both teachers.

One of the criminal acts of Hitler and the Third Reich was to confiscate the riches of the countries they were occupying. It was not the worst of the atrocities, but it was up there. By confiscating the food and money of these countries, the Nazis left the people in those countries broke and starving. Even as the Third Reich began to know they were losing the war, there was hope that they would go into hiding, re-group, and rise again. If that was going to happen, they were going to need money, and the only way to insure that was to begin mass confiscation and hiding of the riches of these nations.

One of the criminal acts of Hitler and the Third Reich was to confiscate the riches of the countries they were occupying. It was not the worst of the atrocities, but it was up there. By confiscating the food and money of these countries, the Nazis left the people in those countries broke and starving. Even as the Third Reich began to know they were losing the war, there was hope that they would go into hiding, re-group, and rise again. If that was going to happen, they were going to need money, and the only way to insure that was to begin mass confiscation and hiding of the riches of these nations.

Lake Toplitz was located in a very remote area of Austria, southeast of Salzburg. In modern day Austria, the area is appropriately called The Dead Mountains. Basically, if you’re looking for somewhere to get away from it all, Lake Toplitz is a good choice. During the war, the lake’s remoteness made it the perfect place for the Nazis to test weapons…including torpedoes. It was also one of the places the Nazi elite fled to when it came time to make their last stand. That fact, in and of itself, makes it a logical place to hide funds for a future comeback of the Third Reich.

In 1945, Hitler’s Germany had only a few more weeks before their horrific reign ended, found themselves stuck in the middle, being crushed by the Russian tanks coming in from the east, and the Americans and British from the north. As their fronts collapsed, the Nazis made several efforts to hide their stolen wealth and treasure. The practice of hiding the wealth is well known, because a lot of that hidden wealth has already been discovered in mines, underground bunkers, and hastily buried fortifications.

Everyone seemed to be looking for the buried treasure left by the Nazis. At one time, a pair of treasure hunters announced they found the location of a buried German armored train in the hills of Poland. Their claim seemed  possible, so a search was held. In the end, it was determined that the “train” was nothing more than an ice covered rock formation. Still, the possibility of a treasure train is very real. Unfortunately, the big news about the “train” caused such a stir that another find was all but lost to the world.

possible, so a search was held. In the end, it was determined that the “train” was nothing more than an ice covered rock formation. Still, the possibility of a treasure train is very real. Unfortunately, the big news about the “train” caused such a stir that another find was all but lost to the world.

There had been stories about plunder the Nazis may have hidden in the cold, deep waters of Lake Toplitz, as the Allies closed in. Reports came out that the lake held iron boxes full of counterfeit British currency and the printing plates to make more…a part of Hitler’s Operation Bernhard, which was a plan to wreck the British economy by flooding the world with fake bank notes. That report turned out to be true, when dive crews recovered several chests stuffed with counterfeit cash in 1959. The divers reported there were more chests stuck in the mud, but they were too deep to recover. More stories about Nazi plunder at the bottom of Lake Toplitz surfaced. The nephew of one German officer made the claim that the Nazis sank chests loaded with gold into the lake. Plates from the lost fabled Russian Imperial Amber Room, which had also been rumored to be on the Nazi gold train in Poland, are also thought by others to be on the bottom of the icy lake. Along with treasure there are stories of weapons components, ammunition, rocket fuel, and maps showing the locations of even more stolen Nazi loot.

There have been many attempts to salvage treasure from the bottom of the lake over the years, with most of them ending in death. The lake is deep and cold, and has many tangled trees and branches that can trap a person. In 1983 the Austrian government declared the lake had been completely searched and anything of value removed. That turned out to be a fake story designed to discourage treasure hunters. Biologists studying the lake have turned up more boxes of counterfeit currency, rocket parts, weapons, mines and even a torpedo  since the government report. Later, photographs from a submerged bunker surfaced, showing boxes with Cyrillic lettering. These are what led to the speculation that the boxes might contain panels from the Amber Room. The exact location of the bunker has been hidden from the public.

since the government report. Later, photographs from a submerged bunker surfaced, showing boxes with Cyrillic lettering. These are what led to the speculation that the boxes might contain panels from the Amber Room. The exact location of the bunker has been hidden from the public.

I expect that people will continue to try to find the treasures, even though claims will most likely be laid upon them immediately after they are located. The people who find them will probably only get the recognition for the find, rather than the right to keep the treasure. Maybe with an attorney who is good enough, they will walk away with a finders fee.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

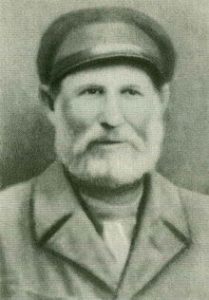

Matvey Kuzmich Kuzmin was born on August 3, 1858 in the village of Kurakino, in the Velikoluksky District of Pskov Oblast. He was a self-employed farmer who declined the offer to join a kolkhoz or collective farm. He lived with his grandson and continued to hunt and fish on the territory of the kolkhoz “Rassvet” (Dawn). He was nicknamed “Biriuk” (lone wolf).

During World War II, the area Kuzmin lived in was occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany. In February 1942, Kuzmin had to help house a German battalion in the village of Kurakino. The German unit was ordered to pierce the Soviet defense in the area of Velikiye Luki by advancing into the rear of the Soviet troops dug in at Malkino Heights. Kuzmin had to do what he had to do…like it or not. On February 13, 1942, the German commander asked the 83 year old Kuzmin to guide his men to the Malkino Heights area, and even offered Kuzmin money, flour, kerosene, and a “Three Rings” hunting rifle for doing so. Kuzmin agreed, but he knew that with information on the proposed route, he could make a difference. He sent his grandson Vasilij to Pershino, about 3.5 miles from Kurakino, to warn the Soviet troops and to propose an ambush near the village of Malkino.

The plan was for Kuzmin to guide the German units through straining paths, through the night. He lead them to  the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

When we think of a bank, we expect that they will have an unlimited amount of money to cover any withdrawals the public might care to make. That thought really isn’t accurate at all. Banks typically hold only a fraction of deposits in cash at any one time, and lend out the rest to borrowers or purchase interest-bearing assets like government securities. As normal banking procedures occur, the money placed in bank care by depositors is loaned out to other people, but then replaced plus interest. The cash flow in the bank normally rolls merrily along in deposits, withdrawals, loans, and payments…as long as nothing goes wrong that is.

When we think of a bank, we expect that they will have an unlimited amount of money to cover any withdrawals the public might care to make. That thought really isn’t accurate at all. Banks typically hold only a fraction of deposits in cash at any one time, and lend out the rest to borrowers or purchase interest-bearing assets like government securities. As normal banking procedures occur, the money placed in bank care by depositors is loaned out to other people, but then replaced plus interest. The cash flow in the bank normally rolls merrily along in deposits, withdrawals, loans, and payments…as long as nothing goes wrong that is.

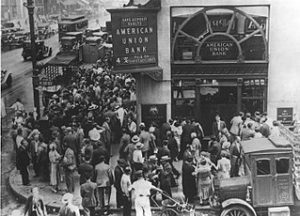

The stock market crash of October 1929 left the American public in a panic, about the economy, the future, and the stability of the banks. People were spending less and so the investments and loans began to decrease, which lead to a decline in production and employment. The ensuing snowball effect was further compounded when the nation’s economic woes led to a series of banking panics or “bank runs,” during which large numbers of anxious people withdrew their deposits in cash, forcing banks to liquidate loans, and ultimately leading to bank failure. The largest collapse was New York’s Bank of the United States in December 1931. The bank had more than $200 million in deposits at the time, making it the largest single bank failure in American history. Wealthy people began pulling their investment assets out of the economy. Bankruptcies were becoming more common, and peoples’ confidence in financial institutions, such as banks, rapidly eroded. Many of those people never fully trusted banks again after that. Some 650 banks failed in 1929, and the number rose to more than 1,300 the following year.

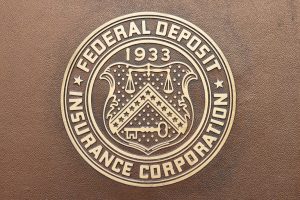

The last wave of bank runs continued through the winter of 1932 and into 1933. By that time, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt had won the presidential election over the Republican incumbent, Herbert Hoover. Almost immediately after taking office in early March, Roosevelt declared a national “bank holiday.” All banks were closed until they were determined to be solvent through federal inspection. Roosevelt called on Congress to come up with new emergency banking legislation to further aid the ailing financial institutions of America. The Banking Act of 1933 established the FDIC, or Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. It also separated commercial and investment banking, and for the first time extended federal oversight to all commercial banks. The FDIC would insure commercial bank deposits of $2,500 (later $5,000) with a pool of money collected from the banks. Small, rural banks were in favor of deposit insurance, but larger banks, who worried they would end up subsidizing smaller banks, opposed it. The public supported deposit insurance overwhelmingly. Many hoped to recover some of the financial losses they had sustained through bank failures and closures. The FDIC did not insure investment products such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds or annuities. No federal law mandated FDIC insurance for banks, though some states required their banks to be federally insured.

In 2007, problems in the subprime mortgage market precipitated the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Twenty-five US banks had failed by late 2008. The most notable bankruptcy was Washington  Mutual Bank, the nation’s largest savings and loan association. A downgrade in the bank’s financial strength in September 2008 caused customers to panic despite Washington Mutual’s status as an FDIC-insured bank. Depositors withdrew $16.7 billion from Washington Mutual Bank over the next nine days. The FDIC subsequently stripped Washington Mutual of its banking subsidiary. It was the largest bank failure in US history. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2011, which permanently raised the FDIC deposit insurance limit to $250,000 per account. The Dodd-Frank Act expanded the FDIC’s responsibilities to include regular risk assessments of all FDIC-insured institutions.

Mutual Bank, the nation’s largest savings and loan association. A downgrade in the bank’s financial strength in September 2008 caused customers to panic despite Washington Mutual’s status as an FDIC-insured bank. Depositors withdrew $16.7 billion from Washington Mutual Bank over the next nine days. The FDIC subsequently stripped Washington Mutual of its banking subsidiary. It was the largest bank failure in US history. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2011, which permanently raised the FDIC deposit insurance limit to $250,000 per account. The Dodd-Frank Act expanded the FDIC’s responsibilities to include regular risk assessments of all FDIC-insured institutions.

I was thinking about Sir Nicholas Winton, who saved 669 Jewish children from the brutal activities, and almost certain death that was being dealt out by Hitler during World War II. Of course, Sir Winton wasn’t the only person who stepped up to help wage their own battle against the Third Reich. Many people in Nazi occupied areas took in families in desperate need. When word is the deportations to the ghettos came down, some parents had to make the horrible choice to give their children to friends and neighbors to “hide” them in plain site, raising them as their own, and everyone hoping to be able to return them to their own parents after the war. The problem was that so many of the parents were killed in the camps.

I was thinking about Sir Nicholas Winton, who saved 669 Jewish children from the brutal activities, and almost certain death that was being dealt out by Hitler during World War II. Of course, Sir Winton wasn’t the only person who stepped up to help wage their own battle against the Third Reich. Many people in Nazi occupied areas took in families in desperate need. When word is the deportations to the ghettos came down, some parents had to make the horrible choice to give their children to friends and neighbors to “hide” them in plain site, raising them as their own, and everyone hoping to be able to return them to their own parents after the war. The problem was that so many of the parents were killed in the camps.

After the war was over, many of these children did not remember their parents. They were too young when they were given to people to care for. That created a new and almost more difficult situation. Some of the foster parents had fallen in love with the children in their care, and the viler knew no other family. Still, they were not their children. It was a heart wrenching situation. The other problem was that due to bombings, many of the homes housing these “hidden” children were gone, and they had no way to let anyone know where they had gone. That made it even more difficult to return the children. And some people couldn’t bear to part with the children anyway.  That left parents devastated and without recourse.

That left parents devastated and without recourse.

Some children were reunited with their parents quickly and some took years…if ever. I wonder about the ones that took years, because of the immense loss they must have felt over so much lost time. You just can’t get that time back, and you can’t change whatever the children endured in their lives. Everyone just had to let go of the past and go forward, as best they could. There was no way to go back to their pre-war lives. Each had changed, some were forever missing, and some were lost to the horrific hatred that was Hitler’s Third Reich.