World War I

There are men of war, and then there are men of war. United States General George S Patton was the latter…meaning that he almost lived for war. Patton was a man who came from a long line of military people, and while he wasn’t always a tactful man, he was a great warrior…a fact that he proved over and over again. Many people didn’t like him much, but they couldn’t deny his capabilities. Patton was a great leader, but he wasn’t really a people person, and that got him in some trouble.

There are men of war, and then there are men of war. United States General George S Patton was the latter…meaning that he almost lived for war. Patton was a man who came from a long line of military people, and while he wasn’t always a tactful man, he was a great warrior…a fact that he proved over and over again. Many people didn’t like him much, but they couldn’t deny his capabilities. Patton was a great leader, but he wasn’t really a people person, and that got him in some trouble.

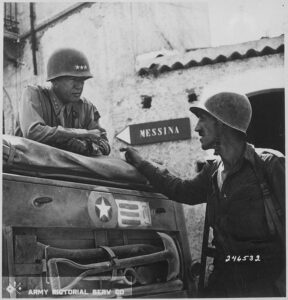

George Smith Patton Jr, who was born to George Smith Patton Sr and his wife, Ruth Wilson, the daughter of Benjamin Davis Wilson on November 11, 1885, in San Gabriel, California. Maybe because of his family history, or maybe it was just him, but Patton never seriously considered a career other than the military. At the age of seventeen he tried for an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He also applied to several universities with Reserve Officer’s Training Corps programs, and was accepted to Princeton College, but eventually decided on Virginia Military Institute (VMI), which his father and grandfather had attended. Later, after studying at West Point, he served as a tank officer in World War I. Patton loved the tank, and his time as a tank officer, as well as his military strategy studies led him to become an advocate of the crucial importance of the tank in future warfare. When the United States entered World War II, Patton became the logical choice for the command of an important US tank division, and his division played a key role in the Allied invasion of French North Africa in 1942. Then, in 1943, in the Allied assault on Sicily, Patton and the US 7th Army in its assault on Sicily and won fame for out-commanding Montgomery during their pincer movement against Messina. Patton loved competition, and this was his chance to shine. On August 17, 1943, Patton and his 7th Army arrived in Messina several hours before British Field Marshal Bernard L Montgomery and his 8th Army, winning the unofficial “Race to Messina” and completing the Allied conquest of Sicily.

Although Patton was one of the most capable American commanders in World War II, he was also one of the most controversial. Patton was a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” kind of guy, and therefore had no personal understanding of fear or fatigue. PTSD, battle fatigue, or shell shock were conditions he could not accept in anyone. In fact, they infuriated him so much that he actually slapped two soldiers who were suffering with the conditions. During the Sicilian campaign, Patton generated considerable controversy when he accused a hospitalized US soldier suffering from battle fatigue of cowardice and then personally struck him across the face. The famously profane general was forced to issue a public apology and was reprimanded by General Dwight Eisenhower. They would have liked to “walk away” from Patton, but when it came time for the invasion of Western Europe, Eisenhower couldn’t find a general as formidable as Patton, so, once again Patton was granted an important military post. In 1944, Patton commanded the US 3rd Army in the invasion of France. Then, in

December of that year Patton’s great expertise in military movement and tank warfare helped to crush the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes.

December of that year Patton’s great expertise in military movement and tank warfare helped to crush the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes.

During one of his many successful campaigns, General Patton was said to have declared, “Compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance.” Patton died in a hospital in Germany on December 21, 1945, from injuries sustained in an automobile accident near Mannheim. He was just 60 years old.

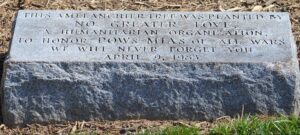

When a soldier goes missing in action, it becomes an unthinkable phenomenon for their family. Really, when anyone goes missing and can’t be found, it is unthinkable for the family, but for a soldier, it’s particularly strange, because we knew where they were and what they were doing, and their disappearance isn’t really connected with anything like an abduction. I suppose it could be classified that way, but Missing In Action (MIA), is not classified as an abduction, but rather an act of war. Often, they were killed in action, and someone other than their company took care of their body. Of course, there is also the possibility that they were taken prisoner of war, but when the prisoners are all released, and our loved one is not among them, we have to face the possibility that something else happened. Every war has its list of Prisoners Of War (POW), and its list of MIAs, and these are people that we hope will never be forgotten, so that maybe someday the truth about what happened can be found out. If they are forgotten, then it is a very real possibility that they will never be found.

When a soldier goes missing in action, it becomes an unthinkable phenomenon for their family. Really, when anyone goes missing and can’t be found, it is unthinkable for the family, but for a soldier, it’s particularly strange, because we knew where they were and what they were doing, and their disappearance isn’t really connected with anything like an abduction. I suppose it could be classified that way, but Missing In Action (MIA), is not classified as an abduction, but rather an act of war. Often, they were killed in action, and someone other than their company took care of their body. Of course, there is also the possibility that they were taken prisoner of war, but when the prisoners are all released, and our loved one is not among them, we have to face the possibility that something else happened. Every war has its list of Prisoners Of War (POW), and its list of MIAs, and these are people that we hope will never be forgotten, so that maybe someday the truth about what happened can be found out. If they are forgotten, then it is a very real possibility that they will never be found.

In every war, there are kind people who will bury the dead of the enemy right along with their own dead, but  often they can’t read the names, so the dead are in an unmarked grave, possibly with their dog tags as the only definitive proof that the remains belong to that soldier. Some of those kind people have remembered where they buried the soldiers, and kept track of the proof of identity, so that maybe, somewhere down the road, they could reunite the soldier with his family…and some of those people have been returned to their families in recent years. The stories, when that happens, are so heart-warming. It reminds us once again, that there is good in this world, even if it’s harder to find these days.

often they can’t read the names, so the dead are in an unmarked grave, possibly with their dog tags as the only definitive proof that the remains belong to that soldier. Some of those kind people have remembered where they buried the soldiers, and kept track of the proof of identity, so that maybe, somewhere down the road, they could reunite the soldier with his family…and some of those people have been returned to their families in recent years. The stories, when that happens, are so heart-warming. It reminds us once again, that there is good in this world, even if it’s harder to find these days.

Of course, it is my opinion that no matter what, God knows where these lost ones are, and that someday people will be reunited with lost loved ones, either here on Earth, or later, in Heaven. That is something I have to believe when I think of anyone who has a lost loved one out there. I personally do not have a lost loved one out there…at least no one I knew personally. I have a great uncle (not sure how many greats) that went  missing when he was forced into war as a result of the German government taking him in the middle of the night, but I never knew him personally. Nevertheless, I feel very sad for those people who have suffered such a loss as this. As of September 18, 2020, the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) lists a total of 85,394 Americans MIA, including 4,422 from World War I, 71,692 from World War II, 7,717 from the Korean War, 1,561 from the Vietnam War. They don’t list any from other conflicts, whether there are missing ones or not.

missing when he was forced into war as a result of the German government taking him in the middle of the night, but I never knew him personally. Nevertheless, I feel very sad for those people who have suffered such a loss as this. As of September 18, 2020, the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) lists a total of 85,394 Americans MIA, including 4,422 from World War I, 71,692 from World War II, 7,717 from the Korean War, 1,561 from the Vietnam War. They don’t list any from other conflicts, whether there are missing ones or not.

When a nation has a weapon that is so deadly to its enemy nations, those nations have no choice but to find a new way to beat that weapon. The German U-Boat was just such a weapon. Gliding along silently beneath the sea, the U-Boat put the ships of the Allied nations in constant and grave danger. That was one of the reasons that the British developed a fixation on their presence at sea. They depended on seaborne trade, and during World War I, the Germans were terrorizing that trade.

When a nation has a weapon that is so deadly to its enemy nations, those nations have no choice but to find a new way to beat that weapon. The German U-Boat was just such a weapon. Gliding along silently beneath the sea, the U-Boat put the ships of the Allied nations in constant and grave danger. That was one of the reasons that the British developed a fixation on their presence at sea. They depended on seaborne trade, and during World War I, the Germans were terrorizing that trade.

For much of Great Britain’s history, they enjoyed the luxury of having more battleships than the next two powers combined. For that reason, the Germans knew that they would have to concentrate their efforts on attacking vulnerable shipping lanes to disrupt the British war effort. They didn’t care if there were passengers on those ships. They didn’t care about loss of life or supplies. They had one plan…to dominate the seas. German submarines became a menace to the merchant navy. Something had to change, so the British came up with a plan to counter the U-boat threat. The plan involved disguising armed vessels as harmless trawlers to  lure the submarines in and then wipe them out. The answer to the U-boat were disguised vessels…decoys, known as Q-ships.

lure the submarines in and then wipe them out. The answer to the U-boat were disguised vessels…decoys, known as Q-ships.

Knowing that the U-Boats were under orders to attack just about anything. The Q-ships hid naval guns behind pivoting panels. It was the Sun Tzu tenet of “hold out baits to entice the enemy.” The Q-ships pretended to be disabled and when the U-Boats show up for the kill, the Q-ships went into action. Guns and additional crew had been concealed by hinges that could be dropped at a moment’s notice. The U-boats of World War I had limited range and carrying capacity, so the captains were nervous about wasting their torpedoes. Also, while the U-Boats of World War II were more capable of lang periods of time submerged, the U-Boats of World War I, had limited capability, so they preferred to use the submarine’s main gun to subdue ships whenever possible.

As the U-Boats came into sight of the Q-ship, the Q-ship’s crew would pretend to panic and abandon the ship to  draw the submarine in close. The U-Boats, once lured in, were at the mercy of the Q-ships. The Q-ships began to drop their depth charges as soon as the submarine tried to escape. It was a dangerous game to play and required a brave crew to pull off the ruse, and it was not always successful. Some Q-ships were lost, but because of their efforts the threat of submarines in World War I were lessened. The plan was to try the tactic again in World War II, but ships were in very short supply. The tactic of using decoy ships was much more limited but was also used by the Germans and Americans. While it wasn’t a major tactical warfare practice during the two wars, it was effective while it was used.

draw the submarine in close. The U-Boats, once lured in, were at the mercy of the Q-ships. The Q-ships began to drop their depth charges as soon as the submarine tried to escape. It was a dangerous game to play and required a brave crew to pull off the ruse, and it was not always successful. Some Q-ships were lost, but because of their efforts the threat of submarines in World War I were lessened. The plan was to try the tactic again in World War II, but ships were in very short supply. The tactic of using decoy ships was much more limited but was also used by the Germans and Americans. While it wasn’t a major tactical warfare practice during the two wars, it was effective while it was used.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

Knox attended school in Washington DC and graduated from the United States Naval Academy on June 5, 1896. Following his graduation, he served in the Spanish-American War aboard the screw steamer Maple in Cuban waters. A screw steamer or screw steamship is an old term for a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine, using one or more propellers…also known as screws…to propel it through the water. These ships were nicknamed iron screw steam ship.

His was a long and distinguished career. During the Philippine-American War, Knox commanded the gunboat Albay, and during the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, the gunboat Iris. He then commanded three of the Navy’s first destroyers…Shubrick, Wilkes, and Decatur. Following his attendance and graduation from the Naval War College in 1912–13, Knox became the aide to Captain William Sims, commanding the Atlantic Torpedo Flotilla. During the cruise of the “Great White Fleet,” he was sent around the world by President Theodore Roosevelt, as an ordnance officer on the battleship Nebraska (BB-14).

He took the lead in developing naval operational doctrine when he published an article of great influence in the US Naval Institute Proceedings in 1915. He was Fleet Ordnance Officer in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and commanding the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station. The job of a Fleet Ordnance Officers is to ensure that weapons systems, vehicles, and equipment are ready and available…and in perfect working order, at all times. These officers also manage the developing, testing, fielding, handling, storage, and disposal of munitions. In November 1917, Knox joined the staff of, by then, Admiral William Sims, Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters. Knox earned the Navy Cross for “distinguished service” while serving as Aide in the Planning Section and later in the Historical Section. He was promoted to Captain on  February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

Also in 1920, Knox first began his work as a naval publicist, serving as naval editor of the Army and Navy Journal until 1923. He then became the naval correspondent of the Baltimore Sun in 1924 – 1946, and naval correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune in 1929. While he was transferred to the Retired List of the Navy on October 20, 1921, he actually and strangely continued on active duty, serving simultaneously as Officer in Charge, Office of Naval Records and Library, and as Curator for the Navy Department. Knox played a key role in creating the Naval Historical Foundation. Early in World War II, he was assigned additional duty as Deputy Director of Naval History.

In a career that spanned half of a century, Knox’s leadership inspired diligence, efficiency, and initiative while he guided, improved, and expanded the Navy’s archival and historical operations. Knox had personal connections to President Roosevelt, Fleet Admiral Ernest J King, and other senior leaders in the Navy Department. These relationships allowed him to play an instrumental role, albeit behind the scenes in the years leading up to and during World War II.

Knox published a number of writings and several books…including his first book “The Eclipse of American Sea Power” (1922) and “A History of the United States Navy” (1936). “A History of the United States Navy” is recognized as “the best one-volume history of the United States Navy in existence.” Through his personal connection with President Roosevelt, he was able to publish key, multi-volume collections of documents on  naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

November 2, 1945, found Knox promoted to Commodore, and awarded the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious conduct” while directing the correlation and preservation of accurate records of the US naval operations in World War II, thus protecting this vital information for posterity. Finally, on June 26, 1946, Knox was relieved of all active-duty work. He died in Bethesda, Maryland, on June 11, 1960. His cause of death is listed as unknown. He was 83 years old.

Recently, oil has taken a huge political hit, but most people know that oil is used for far more than the running vehicles. Oil has provided necessary energy to the United States, and even the electric cars can’t exist without petroleum products to make the wiring, tires, seats, floormats, hoses, and much more. In fact, most of us know that there is almost no area of life that isn’t affected by oil. It is part of the makeup of so many things. So, it is silly to think that we can run anything in this world completely void of oil. Living in Wyoming, I know of the value of oil, and many in my family work or have worked in the oil industry.

Recently, oil has taken a huge political hit, but most people know that oil is used for far more than the running vehicles. Oil has provided necessary energy to the United States, and even the electric cars can’t exist without petroleum products to make the wiring, tires, seats, floormats, hoses, and much more. In fact, most of us know that there is almost no area of life that isn’t affected by oil. It is part of the makeup of so many things. So, it is silly to think that we can run anything in this world completely void of oil. Living in Wyoming, I know of the value of oil, and many in my family work or have worked in the oil industry.

Casper, Wyoming has deep roots in the oil industry, and has long provided necessary energy for the nation. Casper’s roots began early on. In 1895, a man named Mark Shannon and a group of Pennsylvania investors opened the state’s first oil refinery in Casper. It was the beginning of an important economic future for Casper and the state. At first, the refinery was able to produce 100 barrels of lubricants per day…not a lot by today’s standards, but in those days, it was phenomenal. Since then, the oil industry has enjoyed a long and successful history, even if the industry did struggle at times. Wyoming is a “Boom-and-Bust” state. We have always been subject to that cycle.

Nevertheless, the early oil fields were quite successful. The Salt Creek and Shannon fields are located in central  Wyoming. With them came the refineries and later, out of necessity, the tank farm oil storage facilities. Storing large quantities of oil, while relatively safe, faces the inevitable possibility of a fire. Safety was always a goal, but it seems an impossible task to stop all fires. The Casper refinery had their first boiler fire on March 5, 1895. Then came the construction of the Casper Tank Farm. According to the Natrona Tribune, reporting on April 18, 1895, “Workmen are now busy sinking a six-hundred-barrel storage reservoir for crude oil and a number of other new tanks and the machinery necessary to finish all grades of oil will be placed as soon as workmen can do so.” I’m sure this was both for storage and safety, but with oil, there is no guarantee.

Wyoming. With them came the refineries and later, out of necessity, the tank farm oil storage facilities. Storing large quantities of oil, while relatively safe, faces the inevitable possibility of a fire. Safety was always a goal, but it seems an impossible task to stop all fires. The Casper refinery had their first boiler fire on March 5, 1895. Then came the construction of the Casper Tank Farm. According to the Natrona Tribune, reporting on April 18, 1895, “Workmen are now busy sinking a six-hundred-barrel storage reservoir for crude oil and a number of other new tanks and the machinery necessary to finish all grades of oil will be placed as soon as workmen can do so.” I’m sure this was both for storage and safety, but with oil, there is no guarantee.

That fact was never made so clear as it was on June 17, 1921, when lightning caused seven oil tanks to catch fire. This became known as the Midwest Oil Tank Farm Battle…and what a battle it was. In those days there was no set plan for fighting a fire in a refinery or a tank farm. It is something you really pray never happens. When lightning struck…in a very real way, they had to figure out how to get it under control, and not lose all of that oil in the tanks. Someone came up with the idea of piercing the tanks below the fire line, thus allowing the oil to drain into the fire dykes. The oil could then be scooped up and pumped into surrounding tanks that were not involved in the fire. It was definitely a great idea, but how were they going to do that?

After giving it some thought, they decided to use some cannons from World War I. The first shot from the cannon hit high, and the oil gushed out toward the men firing the cannon. I’m sure that with the fires around them they must have panicked at least a little bit. These men weren’t firefighters. They were soldiers, so fire was not the enemy they were used to fighting. In all, nine shots were fired that day. One was aimed at a very high angle, and it flew off into areas unknown. Two of them went very low and were buried in the dirt under the tanks. Six shots were right on target. In the end, the operation was successful, and the fire was finally brought under control.

Many people think of the National Guard as a way to avoid going to war. They think that the Guard is designed to be a type of civil service group, but the reality is that they are a military, or actually a militia group. Never has that fact come to light more than now. The National Guard is considered a part of the reserve components of the United States Army and the United States Air Force. The difference between the regular military forces and the National Guard is that the National Guard usually serves in the United States, and not in wars abroad. Still, the president of the United States can “federalize” the National Guard for military action abroad. Reserve forces, including the guard, have made up about 45 percent of the personnel deployed to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001. While the deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan is currently the case, it is not normal procedure.

Many people think of the National Guard as a way to avoid going to war. They think that the Guard is designed to be a type of civil service group, but the reality is that they are a military, or actually a militia group. Never has that fact come to light more than now. The National Guard is considered a part of the reserve components of the United States Army and the United States Air Force. The difference between the regular military forces and the National Guard is that the National Guard usually serves in the United States, and not in wars abroad. Still, the president of the United States can “federalize” the National Guard for military action abroad. Reserve forces, including the guard, have made up about 45 percent of the personnel deployed to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001. While the deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan is currently the case, it is not normal procedure.

“The National Guard is a military reserve force composed of military members or units from each state and the territories of Guam, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia, for a total of 54 separate organizations. All members of the National Guard of the United States are also members of the organized militia of the United States as defined by 10 U.S.C. § 246. Unlike the other parts of the military, these units are under the dual control of the state governments and the federal government, and can be deployed in disasters like hurricanes, tornados, floods, and even in situations of civil unrest and terrorist attacks.”

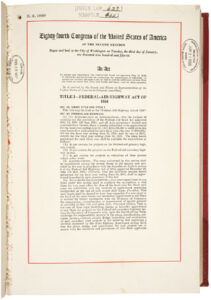

The National Guard was strictly a state-run militia before June 3, 1916, at which time, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the National Defense Act, which expanded the size and scope of the National Guard. Prior to the National Defense Act, the National Guard was used for the needs of each state only. I never really thought about a state-run militia before, but the network of states’ militias that had been developing steadily  since colonial times, was now given the guaranteed status as the nation’s permanent reserve force. In times of the draft, the National Guard didn’t really get deployed. There were always enough soldiers available. It would most likely have to be a long-drawn-out war with many casualties before the National Guard was called out…as in Iraq and Afghanistan.

since colonial times, was now given the guaranteed status as the nation’s permanent reserve force. In times of the draft, the National Guard didn’t really get deployed. There were always enough soldiers available. It would most likely have to be a long-drawn-out war with many casualties before the National Guard was called out…as in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Theodore Roosevelt and other Republicans felt that the United States needed to get into World War I, in the first half of 1916, but with forces from the regular US Army, as well as the National Guard called out to face Mexican rebel leader Pancho Villa during his raids on states in the American Southwest, the need to reinforce the nation’s armed forces and increase US military preparedness became very apparent. The National Defense Act, ratified by Congress in May 1916 and signed by Wilson on June 3, brought the states’ militias more under federal control and gave the president authority, in case of war or national emergency, to mobilize the National Guard for the duration of the emergency. A logical use of the National Guard would have been during the riots seen in our country in 2019. The problem was that each state had to ask for help and some just didn’t.

One provision of the National Defense Act was that the term National Guard was to be used to refer to the combined network of states’ militias that became the primary reserve force for the US Army. The term had first been adopted by New York’s militia in the years before the Civil War in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, a French hero of the American Revolution who commanded the “Garde Nationale” during the early days of the French Revolution in 1789. I guess they liked the name and felt like it accurately depicted the purpose of this  military force. Certain qualifications were also set in the National Defense Act. National Guard officers were allowed to attend Army schools. Also, all National Guard units would now be organized according to the standards of regular Army units. For the first time, National Guardsmen would receive payment from the federal government not only for their annual training…which was increased from 5 to 15 days, but also for their drills, which were also increased, from 24 per year to 48. Finally, the National Defense Act formally established the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) to train high school and college students for Army service.

military force. Certain qualifications were also set in the National Defense Act. National Guard officers were allowed to attend Army schools. Also, all National Guard units would now be organized according to the standards of regular Army units. For the first time, National Guardsmen would receive payment from the federal government not only for their annual training…which was increased from 5 to 15 days, but also for their drills, which were also increased, from 24 per year to 48. Finally, the National Defense Act formally established the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) to train high school and college students for Army service.

In the Battle of Trafalgar, on October 21, 1805, the British Royal Navy took on the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and soundly defeated them. As the French and Spanish Navies came into sight, Admiral Horatio Nelson raised one set of signal flags. His orders were simple and direct, “England expects every man to do his duty.” His men knew exactly what he meant and what was expected of them…fight, and if necessary, die for their country!! Without hesitation, Nelson’s ships closed in on and destroyed their enemy. The victory of this battle has been called the greatest naval victory in history, and for the remainder of the century, the British really had control over the oceans and the world. In the years following that victory, the British grew lackadaisical about keeping a strong military force, and 111 years later, that issue would be evident for the British Royal Navy when they went up against the Germans in the Battle of Jutland.

In the Battle of Trafalgar, on October 21, 1805, the British Royal Navy took on the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), and soundly defeated them. As the French and Spanish Navies came into sight, Admiral Horatio Nelson raised one set of signal flags. His orders were simple and direct, “England expects every man to do his duty.” His men knew exactly what he meant and what was expected of them…fight, and if necessary, die for their country!! Without hesitation, Nelson’s ships closed in on and destroyed their enemy. The victory of this battle has been called the greatest naval victory in history, and for the remainder of the century, the British really had control over the oceans and the world. In the years following that victory, the British grew lackadaisical about keeping a strong military force, and 111 years later, that issue would be evident for the British Royal Navy when they went up against the Germans in the Battle of Jutland.

Apparently not understanding that things were no longer what they used to be, a British naval force commanded by Vice Admiral David Beatty confronted a squadron of German ships, led by Admiral Franz von Hipper, approximately 75 miles off the Danish coast, just before 4:00 on the afternoon of May 31, 1916. In what was later called the greatest naval battle of World War I, the two squadrons opened fire on each other simultaneously, beginning the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland.

Following the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, the German navy knew that they were, at the very least, numerically inferior to the British Royal Navy, so the Germans chose not to engage them in a major battle for more than a year. During that time, they began pursuing a new strategy for their naval warfare…namely, its lethal U-boat submarines. Biding his time, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer waited until May 1916, when the majority of the British Grand Fleet was anchored far away, at Scapa Flow, off the northern coast of Scotland. Then Sheer, the commander of the German High Seas Fleet, believed the time was right to resume attacks on the British coastline. The unique coding system of the U-boats made it very difficult for the British to know what was coming. Scheer ordered 19 U-boat submarines to position themselves for a raid on the North Sea coastal city of Sunderland while using air reconnaissance crafts to keep an eye on the British fleet’s movement  from Scapa Flow. The first planned raid was scrapped because of bad weather, and Scheer instead ordering his fleet, consisting of 24 battleships, five battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and 63 destroyers, to head north, to the Skagerrak, a waterway located between Norway and northern Denmark, off the Jutland Peninsula, where they could attack Allied shipping interests…hoping to punch a hole in the stringent British blockade.

from Scapa Flow. The first planned raid was scrapped because of bad weather, and Scheer instead ordering his fleet, consisting of 24 battleships, five battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and 63 destroyers, to head north, to the Skagerrak, a waterway located between Norway and northern Denmark, off the Jutland Peninsula, where they could attack Allied shipping interests…hoping to punch a hole in the stringent British blockade.

Truly, the only thing that saved the British Grand Fleet that night was that unbeknownst to Scheer, a newly created intelligence unit located within an old building of the British Admiralty, known as Room 40, had cracked the German codes and warned the British Grand Fleet’s commander, Admiral John Rushworth Jellicoe, of Scheer’s intentions. So, the night before the planned attack…May 30, 1916, a British fleet of 28 battleships, nine battle cruisers, 34 light cruisers, and 80 destroyers set out from Scapa Flow, bound for positions off the Skagerrak.

Then, on May 31, 1916, at 2:20pm, Beatty, leading a British squadron, spotted Hipper’s warships. The squadrons quickly maneuvered south to get a better position, and shots were fired at about 3:48 that afternoon. They fought for 55 minutes, the British losing two British battle cruisers, Indefatigable and Queen Mary. Over 2,000 sailors lost their lives in the battle. At 4:43pm, Hipper’s squadron was joined by the remainder of the German fleet, commanded by Scheer. The British were out gunned, and Beatty was forced to fight a delaying action for the next hour, until Jellicoe could arrive with the rest of the Grand Fleet.

Once both entire fleets were there, they faced off. It was a huge battle of naval strategy between the four commanders, and particularly between Jellicoe and Scheer. As the fleets continued to engage each other throughout the late evening and the early morning of June 1, Jellicoe maneuvered 96 of the British ships into a V-shape surrounding 59 German ships. Hipper’s flagship, Lutzow, was disabled by 24 direct hits, but was still able to sink the British battle cruiser Invincible, before it sank too. Just after 6:30 on the evening of June 1, Scheer’s fleet executed a previously planned withdrawal under cover of darkness to their base at the German port of Wilhelmshaven, ending the battle and cheating the British of the major win they had envisioned.

The Battle of Jutland…or the Battle of the Skagerrak, as it was known to the Germans, involved a total of 100,000 men aboard 250 ships over the course of 72 hours. The Germans, claimed vistory, and the British had to agree…at first anyway. The German navy lost 11 ships, including a battleship and a battle cruiser, and 3,058 men lost their lives. The British losses were heavier, with 14 ships sunk, including three battle cruisers, and 6,784 lives lost. The only thing that made the British losses seem less was that ten more German ships had suffered heavy damage, and by June 2, 1916, only 10 of the German ships that had been involved in the battle were ready to leave port again. Jellicoe, on the other hand, could have put 23 British ships to sea. On July 4, 1916, Scheer reported to the German high command that further fleet action was not an option, and that  submarine warfare was Germany’s best hope for victory at sea. Despite the missed opportunities and heavy losses, the Battle of Jutland had left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, but if they had been better prepared, they might have held a place of domination over the Germans then. When a nation decides to sit back and ride on its reputation, rather than continue a practice of a strong military force, that nation can find itself in a tough spot when the enemy attacks. The British could have had a very different outcome, but maybe better aim or the favor of God held the German High Seas Fleet at bay. They made no further attempts to break the Allied blockade or cross the Grand Fleet for the rest of World War I.

submarine warfare was Germany’s best hope for victory at sea. Despite the missed opportunities and heavy losses, the Battle of Jutland had left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, but if they had been better prepared, they might have held a place of domination over the Germans then. When a nation decides to sit back and ride on its reputation, rather than continue a practice of a strong military force, that nation can find itself in a tough spot when the enemy attacks. The British could have had a very different outcome, but maybe better aim or the favor of God held the German High Seas Fleet at bay. They made no further attempts to break the Allied blockade or cross the Grand Fleet for the rest of World War I.

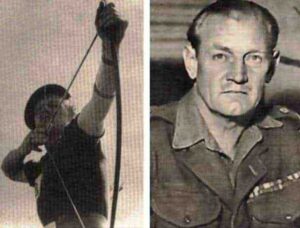

Most soldiers know that when you are trying to sneak up on your enemy, it’s probably best to leave the bagpipe playing at home. Nevertheless, John “Mad Jack” Churchill, who was one of the most colorful and unusual soldiers to fight in World War II, might find just about anything…you just never knew. The British-born “Mad Jack” Churchill had no known relation to Prime Minister Winston Spencer-Churchill, although I would not be surprised to find there was a relation. He was known for carrying a Scottish Claymore Sword into battle, and felt that any officer who didn’t have one while going into battle, was basically out of uniform. “Mad Jack”was also an avid archer and bagpipe player and brought both of these hobbies onto the battlefield.

Most soldiers know that when you are trying to sneak up on your enemy, it’s probably best to leave the bagpipe playing at home. Nevertheless, John “Mad Jack” Churchill, who was one of the most colorful and unusual soldiers to fight in World War II, might find just about anything…you just never knew. The British-born “Mad Jack” Churchill had no known relation to Prime Minister Winston Spencer-Churchill, although I would not be surprised to find there was a relation. He was known for carrying a Scottish Claymore Sword into battle, and felt that any officer who didn’t have one while going into battle, was basically out of uniform. “Mad Jack”was also an avid archer and bagpipe player and brought both of these hobbies onto the battlefield.

Churchill volunteered for Great Britain’s first-ever commando unit in 1941, and he participated in covert operations in Italy and Norway. In one Norway operation, he played his bagpipes on the landing craft as they approached the shore, then picked up his sword and attacked. In 1944, “Mad Jack” was on assignment in Yugoslavia to assist with the communist partisans under Josip “Tito” Broz, and that was when his infamous bagpipe incident happened.

During a mission to attack a German position on the Island of Brac, “Mad Jack” and his men advanced under heavy fire. In the end, he was the only one left alive. After running out of bullets, and in typical “Mad Jack” style, he picked up his bagpipe and played “Will Ye No Come Back Again?,l.” It was an 18th-century song celebrating the Jacobite Prince Charles III’s escape from being captured by the British monarchy.

Unimpressed, the Germans knocked him out with an explosion and captured him, but they spared his life…not because of his bagpipe prowess, however, but because they thought he was related to Prime Minister Winston Spencer-Churchill. They thought that having a relative of the prime minister would provide them with sone leverage. Unfortunately for them, as far as anyone knew there was no connection. “Mad Jack” was placed in a prison camp, from which he escaped captivity twice before making it home.

Churchill married Rosamund Margaret Denny, the daughter of Sir Maurice Edward Denny and granddaughter of Sir

Archibald Denny, on March 8, 1941. They had two children, Malcolm John Leslie Churchill, born 1942, and Rodney Alistair Gladstone Churchill, born 1947. He also had a grandson named James Also stair Gladstone Churchill. “Mad Jack” lived a long and happy life. Nevertheless, I seriously doubt if any part of it was as crazy as the time he spent in World War I. He passed away on March 8, 1996 at 89 years old, in the county of Surrey.

Archibald Denny, on March 8, 1941. They had two children, Malcolm John Leslie Churchill, born 1942, and Rodney Alistair Gladstone Churchill, born 1947. He also had a grandson named James Also stair Gladstone Churchill. “Mad Jack” lived a long and happy life. Nevertheless, I seriously doubt if any part of it was as crazy as the time he spent in World War I. He passed away on March 8, 1996 at 89 years old, in the county of Surrey.

Imagine a time when there was no air force, or for that matter, airplanes. Of course, for those of us living today, that would be very hard to imagine…in fact, maybe impossible. Nevertheless, before the Wright brothers made flight possible, there was not only no planes, but no air force. Then, in 1914, things were about to change forever.

Imagine a time when there was no air force, or for that matter, airplanes. Of course, for those of us living today, that would be very hard to imagine…in fact, maybe impossible. Nevertheless, before the Wright brothers made flight possible, there was not only no planes, but no air force. Then, in 1914, things were about to change forever.

The First Aero Squadron was formed in 1914. It was organized after the start of World War I, but it was first used because of the Mexican revolutionary, Pancho Villa, who was initially a bandit, but later became a general in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary violence that forced out President Porfirio Díaz and brought Francisco Madero to power in 1911. Pancho Villa was an excellent guerrilla leader who fought against the regimes of both of those men. After 1914, he engaged in civil war and banditry. He became notorious in the United States for his attack on Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916, and something had to be done

On March 9, 1916, Villa, who opposed American support for Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, led a band of several hundred guerrillas across the border on a raid of the town of Columbus, New Mexico. Seventeen Americans were killed in the battle. On March 15, President Woodrow Wilson ordered, US Brigadier General John J Pershing to launch a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture Villa. Four days later, the First Aero Squadron was sent into Mexico to scout and relay messages for General Pershing. On March 19, 1914, Eight Curtiss “Jenny” planes of the First Aero Squadron took off from Columbus, New Mexico, in the first combat air mission in United States history. The squadron was on a support mission for the 7,000 US troops who invaded Mexico to capture Villa.

Despite encountering numerous mechanical and navigational problems, the American pilots flew hundreds of missions for Pershing during which they gained important experience that would later be used by fliers over the battlefields of Europe. Unfortunately, during the 11-month mission, US forces failed to capture the elusive revolutionary, and Mexican resentment over US intrusion into their territory led to a diplomatic crisis. In late January 1917, with President Wilson under pressure from the Mexican government and more concerned with the war overseas than with bringing Villa to justice, the Americans were ordered home. The missions were over.

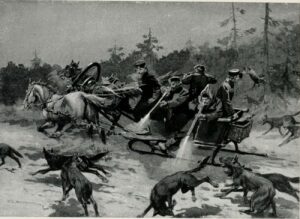

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

The intense fighting throughout the heavily forested region and had an unexpected side effect. Any time humans move into an area, the animal  population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

The wolves had progressed from raiding villages to taking corpses to accosting groups of soldiers outright, so  the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.

the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.