storm

My sister, Alena Stevens has been retired now for two years, and while you might this is a time in her life when things slow down and she finds herself with lots of time on her hands, you would be wrong. Alena has a granddaughter in Sheridan, Wyoming named Elliott Stevens, and a little sister coming in June. That makes for lots of trips to Sheridan to see those sweet little granddaughters. Of course, Alena doesn’t mind making those trips one little bit, because as we all know, grandbabies are the greatest blessings ever. Alena has also found herself with two bonus grandchildren, and she couldn’t be happier about that. Brooklyn and Jaxon Killinger are the children of her youngest child, Lacey’s boyfriend, Chris Killinger. Alena has wanted to be a grandmother for a long time, and when that got going, it has really snowballed. Right now, she is just enjoying that “snowball” effect. And waiting for the next “storm” of babies.

My sister, Alena Stevens has been retired now for two years, and while you might this is a time in her life when things slow down and she finds herself with lots of time on her hands, you would be wrong. Alena has a granddaughter in Sheridan, Wyoming named Elliott Stevens, and a little sister coming in June. That makes for lots of trips to Sheridan to see those sweet little granddaughters. Of course, Alena doesn’t mind making those trips one little bit, because as we all know, grandbabies are the greatest blessings ever. Alena has also found herself with two bonus grandchildren, and she couldn’t be happier about that. Brooklyn and Jaxon Killinger are the children of her youngest child, Lacey’s boyfriend, Chris Killinger. Alena has wanted to be a grandmother for a long time, and when that got going, it has really snowballed. Right now, she is just enjoying that “snowball” effect. And waiting for the next “storm” of babies.

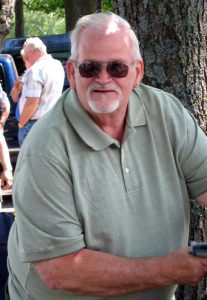

While Alena doesn’t mind driving to Sheridan alone, the fact that her husband, Mike is retiring July 1st after 39 years in the oilfield business, means that now they can both make the trips to see the granddaughters. They also plan to do lots of camping, traveling, and golfing too. If I know my sister, there will also be some redecorating, remodeling, or re-envisioning changes to their home too, so I’m sure they will be busy with that. Alena should have been an interior decorator, so there are always ideas rolling around in her head. Don’t get me wrong, Alena was an amazing special education aid, but she is also a gifted decorator, and her home shows that off nicely. Alena has an eye for color, and a natural flair for the glamorous.

Alena has also been working on getting slim and healthy this past year…and she looks amazing. She loves sharing the recipes she uses, and plenty of low carb healthy alternatives to everyday recipes too. She has been quite focused on soups lately, and the ideas she has are amazing. A lot of times, the spouse of the “dieter” has no desire to eat any of the food that the “dieter” is eating, but Alena has been able to tempt Mike to eat lots of the recipes she is using, so it’s a healthy lifestyle for both of them these days. As anyone who knows Alena can see, she looks absolutely amazing these days, and we are all very proud of her transformation. Today is Alena’s birthday. Happy birthday Alena!! Have a great day and keep up the good work!! We love you!!

Alena has also been working on getting slim and healthy this past year…and she looks amazing. She loves sharing the recipes she uses, and plenty of low carb healthy alternatives to everyday recipes too. She has been quite focused on soups lately, and the ideas she has are amazing. A lot of times, the spouse of the “dieter” has no desire to eat any of the food that the “dieter” is eating, but Alena has been able to tempt Mike to eat lots of the recipes she is using, so it’s a healthy lifestyle for both of them these days. As anyone who knows Alena can see, she looks absolutely amazing these days, and we are all very proud of her transformation. Today is Alena’s birthday. Happy birthday Alena!! Have a great day and keep up the good work!! We love you!!

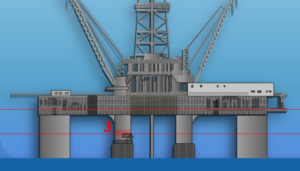

Over the years, we have gotten used to seeing offshore drilling rigs in the oceans surrounding our country, and other countries too, I’m sure. Generally, these rigs are safe places to work, but it’s hard to guarantee safety in some of the fierce storms that occur around the globe. Ocean Ranger was a semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit that was located 166 miles east of Saint John’s, Newfoundland. Ocean Ranger was designed and owned by Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company Inc (ODECO) of New Orleans. Ocean Ranger was actually a self-propelled large semi-submersible vessel, designed with a drilling facility and living quarters. It was capable of operation beneath 1,500 feet of ocean water and could drill to a maximum depth of 25,000 feet. At the time of its launch, it was described by ODECO as the world’s largest semi-submersible oil rig to date.

Over the years, we have gotten used to seeing offshore drilling rigs in the oceans surrounding our country, and other countries too, I’m sure. Generally, these rigs are safe places to work, but it’s hard to guarantee safety in some of the fierce storms that occur around the globe. Ocean Ranger was a semi-submersible mobile offshore drilling unit that was located 166 miles east of Saint John’s, Newfoundland. Ocean Ranger was designed and owned by Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company Inc (ODECO) of New Orleans. Ocean Ranger was actually a self-propelled large semi-submersible vessel, designed with a drilling facility and living quarters. It was capable of operation beneath 1,500 feet of ocean water and could drill to a maximum depth of 25,000 feet. At the time of its launch, it was described by ODECO as the world’s largest semi-submersible oil rig to date.

Ocean Ranger was constructed for ODECO in 1976 by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Hiroshima, Japan. It was 396 feet long, 262 feet wide, and 337 feet high. It had twelve 45,000-pound anchors. The weight was 25,000 tons. It was floating on two 400-foot-long pontoons that rested 79 feet below the surface. It was massive and very impressive, and it was approved for “unrestricted ocean operations.” Prior to moving to the Grand Banks area in November 1980, it had operated off the coasts of Alaska, New Jersey and Ireland.

On November 26, 1981, Ocean Ranger commenced drilling well J-34, its third well in the Hibernia Oil Field. Ocean Ranger was still working on this well in February 1982 when the incident occurred. Ocean Ranger was designed to withstand extremely harsh conditions at sea, including 100-knot winds and 110-foot waves, but the  storm off of Canada on February 14, 1982, would prove to be too much for it. Two other semi-submersible platforms were drilling nearby Ocean Ranger on that fateful day. Sedco 706 was 8.5 miles NNE, and Zapata Ugland was 19.2 miles N of Ocean Ranger. On February 14, 1982, the platforms received reports of an approaching storm linked to a major Atlantic cyclone from NORDCO Ltd, the company responsible for issuing offshore weather forecasts. There were protocols in place, and the crew began preparing for bad weather. They began hanging-off the drill pipe at the sub-sea wellhead and disconnecting the riser from the sub-sea blowout preventer. They worked hard, but due to surface difficulties and the speed at which the storm developed, the crew of Ocean Ranger were forced to shear the drill pipe after hanging-off, after which they disconnected the riser in the early evening.

storm off of Canada on February 14, 1982, would prove to be too much for it. Two other semi-submersible platforms were drilling nearby Ocean Ranger on that fateful day. Sedco 706 was 8.5 miles NNE, and Zapata Ugland was 19.2 miles N of Ocean Ranger. On February 14, 1982, the platforms received reports of an approaching storm linked to a major Atlantic cyclone from NORDCO Ltd, the company responsible for issuing offshore weather forecasts. There were protocols in place, and the crew began preparing for bad weather. They began hanging-off the drill pipe at the sub-sea wellhead and disconnecting the riser from the sub-sea blowout preventer. They worked hard, but due to surface difficulties and the speed at which the storm developed, the crew of Ocean Ranger were forced to shear the drill pipe after hanging-off, after which they disconnected the riser in the early evening.

A Mayday call was sent out from Ocean Ranger at 12:52am local time, on February 15th, noting a severe list to the port side of the rig and requesting immediate assistance. This was the first communication from Ocean Ranger identifying a major problem. The standby vessel, the M/V Sea-forth Highlander, was requested to come in close, because countermeasures against the 10–15-degree list weren’t working. The onshore MOCAN supervisor was notified of the situation, and the Canadian Forces and Mobil-operated helicopters were alerted just after 1:00 local time. The M/V Boltentor and the M/V Nordertor, the standby boats of Sedco 706 and Zapata Ugland respectively, were also dispatched to Ocean Ranger to provide assistance. Everything happened so fast, and at 1:30am local time, Ocean Ranger transmitted its last message: “There will be no further radio communications from Ocean Ranger. We are going to lifeboat stations.” Shortly thereafter, in the middle of the  night and in the midst of that severe winter storm, the crew abandoned the platform. The platform remained afloat for another ninety minutes, sinking between 3:07am and 3:13am local time. All of Ocean Ranger sank beneath the Atlantic and by the next morning only a few buoys remained. Her entire crew of 84 workers…46 Mobil employees and 38 contractors from various service companies…were killed. There was evidence on at least one lifeboat launched with about 36 people onboard, but they didn’t survive either. Over the next week, 22 bodies were recovered from the North Atlantic. Autopsies indicated that those men had died as a result of drowning while in a hypothermic state.

night and in the midst of that severe winter storm, the crew abandoned the platform. The platform remained afloat for another ninety minutes, sinking between 3:07am and 3:13am local time. All of Ocean Ranger sank beneath the Atlantic and by the next morning only a few buoys remained. Her entire crew of 84 workers…46 Mobil employees and 38 contractors from various service companies…were killed. There was evidence on at least one lifeboat launched with about 36 people onboard, but they didn’t survive either. Over the next week, 22 bodies were recovered from the North Atlantic. Autopsies indicated that those men had died as a result of drowning while in a hypothermic state.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

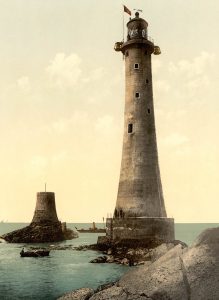

Finally, on November 27, 1703, the storm system finally dissipated over England. For almost two weeks, it had ripped the country nearly to shreds. With its hurricane force winds, the storm killed somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 people. Hundreds of Royal Navy ships were lost to the storm, the worst in Britain’s history. It was the loss of the 300 Royal Navy ships that really caused the death toll to rise. The ships that were anchored carried some 8,000 sailors. All were lost. Then, the Eddystone Lighthouse, which had been built on a  rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

The author Daniel Defoe, witnessed the storm, and it had such an impact on him that he wrote his first book, entitled “The Storm” the following year. In “The Storm” he described the storm as an “Army of Terror in its furious March.” Sometimes the best inspiration for writing a book is the events of real life. Defoe would later go on to write the well known novel “Robinson Crusoe.”

The ship, SS Daniel J. Morrell was a 603 foot Great Lakes freighter, first launched August 22, 1906. It was operated by Cambria Steamship Company. The freighter was used to carry bulk cargoes such as iron ore. SS Daniel J. Morrell was named for Daniel Johnson Morrell, a Republican member of the US House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. In 1855 he moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and became general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, which was the greatest manufacturer of iron and steel in the United States until the Johnstown Flood. As a former general manager of Cambria Steamship Company…Morrell died August 20, 1885…naming the ship after him made sense.

The ship, SS Daniel J. Morrell was a 603 foot Great Lakes freighter, first launched August 22, 1906. It was operated by Cambria Steamship Company. The freighter was used to carry bulk cargoes such as iron ore. SS Daniel J. Morrell was named for Daniel Johnson Morrell, a Republican member of the US House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. In 1855 he moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and became general manager of the Cambria Iron Company, which was the greatest manufacturer of iron and steel in the United States until the Johnstown Flood. As a former general manager of Cambria Steamship Company…Morrell died August 20, 1885…naming the ship after him made sense.

SS Daniel J. Morrell, along with her sister ship, SS Edward Y. Townsend were making the last run of the season. On November 29, 1966, they encountered a storm with winds exceeding 70 miles per hour and swells that topped the height of the ship, at 20 to 25 feet. Edward Y. Townsend decided to take shelter in the St. Clair River. That left Daniel J. Morrell alone on the waters north of Pointe Aux Barques, Michigan, heading for the protection of Thunder Bay. As the storm grew worse, and at 2:00pm, the Morrell began to break up, which forced the crew onto the deck. Many of the crew panicked and jumped to their deaths in the 34° Lake Huron waters. At 2:15pm, the ship’s hull broke and allowed water to pour in, and the remaining crewmen loaded into a raft on the bow of the vessel. While they waited for the ship to break up and the raft to be thrown into the lake, there were shouts that a ship had been spotted off the port bow. Unfortunately, moments later, it became clear that  the looming object was not another ship, but Daniel J. Morrell’s aft section, barreling towards them under the power of the ship’s engine. The ship broke apart, throwing the rafts into the water heading into the distance.

the looming object was not another ship, but Daniel J. Morrell’s aft section, barreling towards them under the power of the ship’s engine. The ship broke apart, throwing the rafts into the water heading into the distance.

Tragically, Daniel J. Morrell was not reported missing until 12:15pm the following afternoon, November 30th. By then, the vessel was overdue at her destination, Taconite Harbor, Minnesota. The US Coast Guard issued a “be on the lookout” alert and dispatched several vessels and aircraft to search for the missing freighter. At around 4:00pm on November 30th, a Coast Guard helicopter located the lone survivor, 26-year-old Watchman Dennis Hale, near frozen and floating in a life raft with the bodies of three of his crewmates. Hale had survived the nearly 40 hour ordeal in frigid temperatures wearing only a pair of boxer shorts, a lifejacket, and a pea coat. Since his crewmates had passed away, poor Hale was left alone with his thoughts…trying to avoid thinking about the cold bodies lying next to him. The survey of the wreck found the shipwreck in 220 feet of water with the two sections 5 miles apart.

Lost in the tragic sinking were Norman M. Bragg, Stuart A. Campbell, John J. Cleary Jr, Arthur I. Crawley, George A. Dahl, Larry G. Davis, Arthur S. Fargo, Charles H. Fosbender, Saverio Grippi, John M. Groh (missing),  Nicholas P. Homick, Phillip E. Kapets, Chester Konieczka, Duncan R. MacLeod, Joseph A. Mahsem, Valmour A. Marchildon, Ernest G. Marcotte, Alfred G. Norkunas, David L. Price, Henry Rischmiller, Stanley J. Satlawa (missing), John H. Schmidt, Charles J. Sestakauskas, Wilson E. Simpson, Arthur E. Stojek, Leon R. Truman, Albert P. Wieme, and Donald E. Worcester. The remains of 26 of the 28 lost crewmen were eventually recovered, with most of them found in the days following the sinking. Still, bodies from Daniel J. Morrell continued to be found well into May of the following year. The two men whose bodies were never recovered were declared legally dead in May 1967. The sole survivor of the sinking, Dennis Hale, died of cancer on September 2, 2015, at the age of 75.

Nicholas P. Homick, Phillip E. Kapets, Chester Konieczka, Duncan R. MacLeod, Joseph A. Mahsem, Valmour A. Marchildon, Ernest G. Marcotte, Alfred G. Norkunas, David L. Price, Henry Rischmiller, Stanley J. Satlawa (missing), John H. Schmidt, Charles J. Sestakauskas, Wilson E. Simpson, Arthur E. Stojek, Leon R. Truman, Albert P. Wieme, and Donald E. Worcester. The remains of 26 of the 28 lost crewmen were eventually recovered, with most of them found in the days following the sinking. Still, bodies from Daniel J. Morrell continued to be found well into May of the following year. The two men whose bodies were never recovered were declared legally dead in May 1967. The sole survivor of the sinking, Dennis Hale, died of cancer on September 2, 2015, at the age of 75.

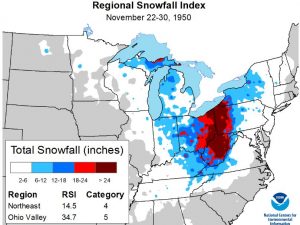

As winter arrived in Coburn Creek, West Virginia in 1950, a storm of epic proportions was about to set some serious records. From November 22 to 30, a slow-moving, powerful storm system dumped heavy snow across much of the central Appalachians. The storm would be remembered as as “The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950,” and it blanketed areas from western Pennsylvania southward deep into West Virginia with over 30 inches of snow. Several locations even received more than 50 inches of snow. Coburn Creek, West Virginia, reported the greatest snowfall total…a staggering 62 inches. Most towns can be shut own with 24 inches, so 62 inches was unthinkable. There is no way a car can get through that, in fact it will take hours to get a snowplow through it. For all intents and purposes, much of the Appalachian Mountains, and especially the Coburn Creek area were at a standstill.

As winter arrived in Coburn Creek, West Virginia in 1950, a storm of epic proportions was about to set some serious records. From November 22 to 30, a slow-moving, powerful storm system dumped heavy snow across much of the central Appalachians. The storm would be remembered as as “The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950,” and it blanketed areas from western Pennsylvania southward deep into West Virginia with over 30 inches of snow. Several locations even received more than 50 inches of snow. Coburn Creek, West Virginia, reported the greatest snowfall total…a staggering 62 inches. Most towns can be shut own with 24 inches, so 62 inches was unthinkable. There is no way a car can get through that, in fact it will take hours to get a snowplow through it. For all intents and purposes, much of the Appalachian Mountains, and especially the Coburn Creek area were at a standstill.

The cold front was massive, with frigid air stretching from the Northeast into the Ohio Valley and all the way down into the far Southeast. Temperatures fell to 22°F in Pensacola, Florida, 5°F in Birmingham, Alabama, 3°F in Atlanta, Georgia, and 1°F in Asheville, North Carolina. This record cold led to widespread crop damage, particularly in Georgia and South Carolina. In the north, intense winds associated with the storm caused extensive tree damage, power outages, and coastal flooding in New England. In New Hampshire, Mount Washington observed gusts as high as 160 mph. And, onshore winds along the coast caused extreme high tides and flooding in New Jersey and Connecticut. The storm was fairly short lived, and the temperatures quickly returned to normal in the first week of December 1950, bringing a whole new problem with them. The rise in temperatures led to a fast snowmelt, flooding several tributaries and major rivers. The Ohio River reached 28.5 feet, 4 feet above flood stage, in Pittsburgh. In Cincinnati, it reached 56 feet, also 4 feet above flood stage.

At the time, the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 was one of the costliest storms on record, and it contributed to at least 160 deaths. Overall, on the Regional Snowfall Index (RSI) this powerful storm ranked as a Category 5…the worst category, for the Ohio Valley, and a Category 4 for the Northeast of the 212 storms our scientists have analyzed for the region. The RSI value of 34.7 securely locks its first place rank, well above the 24.6 RSI value second worst storm in March 1993. Only four Category 5 storms have impacted the Ohio Valley since 1900, so it is highly uncommon. During the storm, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, received 30.2 inches of snow, and both Erie, Pennsylvania, and Youngstown, Ohio, received more than 28 inches of snow. Across the region, over 18 inches of snow affected more than 6.1 million people. Such high snowfall totals affecting so many people largely contributed to the storm’s high ranking on the RSI scale.

In the Northeast region, the Great Appalachian Storm ranks as the ninth worst storm to impact the area out of the 203 analyzed. That fact seems surprising given the severity of the storm. I would have expected a much higher ranking. Over 30 inches of snow affecting 1.3 million people in the region largely contributed to the regional RSI value of 14.5. With that value, it ranks just behind the more recent February 2003, February 2010, and January 2016 storms. The late February snowstorm of 1969 remains the strongest storm to hit the

Northeast, with an RSI value of 34.0 making it a Category 5 or “Extreme” event. The March 1993 “Storm of the Century” remains the second strongest snowstorm to hit the Northeast, with an RSI value of 22.1 also making it a Category 5 event. As I look out my window at the light snow falling, I find myself feeling grateful that this storm is not expected to be anything like the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

Northeast, with an RSI value of 34.0 making it a Category 5 or “Extreme” event. The March 1993 “Storm of the Century” remains the second strongest snowstorm to hit the Northeast, with an RSI value of 22.1 also making it a Category 5 event. As I look out my window at the light snow falling, I find myself feeling grateful that this storm is not expected to be anything like the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

The other day I watched a documentary about the Yukon Gold Rush. Each prospector was required by the Canadian authorities, to bring a year’s supply of food in order to prevent starvation. In all, their equipment weighed close to a ton, which for most had to be carried in stages by themselves. Together with mountainous terrain and cold climate, this meant that those who persisted did not arrive until summer 1898. It wasn’t that the border patrol was being difficult, but rather that they knew that if these prospectors were to survive the extreme weather of the Yukon Territory, they were going to need every bit of those supplies, and sometimes more. It is estimated that 100,000 prospectors who headed north to the Yukon Territory between 1897 and 1898. Of those 100,000, it is estimated that 30,000 to 40,000 actually arrived in the gold fields, and of those who actually reached Dawson City during the gold rush, only around 15,000 to 20,000 finally became prospectors. The odd were certainly stacked against them.

The other day I watched a documentary about the Yukon Gold Rush. Each prospector was required by the Canadian authorities, to bring a year’s supply of food in order to prevent starvation. In all, their equipment weighed close to a ton, which for most had to be carried in stages by themselves. Together with mountainous terrain and cold climate, this meant that those who persisted did not arrive until summer 1898. It wasn’t that the border patrol was being difficult, but rather that they knew that if these prospectors were to survive the extreme weather of the Yukon Territory, they were going to need every bit of those supplies, and sometimes more. It is estimated that 100,000 prospectors who headed north to the Yukon Territory between 1897 and 1898. Of those 100,000, it is estimated that 30,000 to 40,000 actually arrived in the gold fields, and of those who actually reached Dawson City during the gold rush, only around 15,000 to 20,000 finally became prospectors. The odd were certainly stacked against them.

On man, in particular, was of interest to me. His name was Albert J Goddard. Goddard was an American politician in the state of Washington. He served in the Washington House of Representatives from 1895 to 1897, but he also made the gold rush run during the stampede years. He had a very unique way of doing this, however. Goddard built a sternwheeler-utility boat, for use in the Yukon gold rush. The boat was named for him…the A. J. Goddard. What really interested me was that Goddard made several trips north with parts for the boat. The border patrol basically looked at him as if he was crazy. His load was extremely heavy, and they were certain that he would not make it. Nevertheless, when he got to the headwater lakes, he proceeded to put together his boat. Many of the people who met there to build their boats, were very inexperienced in boat building, and consequently, many of the boats didn’t fare well. The A. J. Goddard was the exception to the rule. Albert Goddard was the exception. He knew what he was doing, and his ship was a good one for all the years he used it. For Albert, the gold rush was not about prospecting for gold. I don’t know if he instinctively knew

that very few people would be successful or not, but his plan was to be a transport boat to bring other prospectors to the gold fields. The A. J. Goddard made one trip to Dawson during the gold rush, was sold, and sank in a storm on Lake Laberge in 1901. I guess Goddard go out just in time, or maybe the endeavor was just not what he had in mind. The boat was rediscovered largely intact in 2008. On board the boat were artifacts of the period such as a gramophone with ontemporary recordings.

that very few people would be successful or not, but his plan was to be a transport boat to bring other prospectors to the gold fields. The A. J. Goddard made one trip to Dawson during the gold rush, was sold, and sank in a storm on Lake Laberge in 1901. I guess Goddard go out just in time, or maybe the endeavor was just not what he had in mind. The boat was rediscovered largely intact in 2008. On board the boat were artifacts of the period such as a gramophone with ontemporary recordings.

In the years between 1791 and 1794, a man named Captain George Vancouver was exploring the Pacific Northwest area which would eventually become part of the United States of America. Captain Vancouver was the commander of the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships sent to survey the northern Pacific Ocean. It was Vancouver and his crew who first recorded the sighting of Mount Saint Helens, and the first to explore Puget Sound. Following the coasts of Oregon and Washington and intending to explore every bay and outlet of the region, he sent men in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

In the years between 1791 and 1794, a man named Captain George Vancouver was exploring the Pacific Northwest area which would eventually become part of the United States of America. Captain Vancouver was the commander of the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships sent to survey the northern Pacific Ocean. It was Vancouver and his crew who first recorded the sighting of Mount Saint Helens, and the first to explore Puget Sound. Following the coasts of Oregon and Washington and intending to explore every bay and outlet of the region, he sent men in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

Vancouver commanded a variety of ships to complete his mission, so while the smaller vessels explored the many channels and rivers along the coast, the larger ships, including the Armed Tender of the HMS Discovery, called the Chatham, often anchored in safe harbors. On April 29, 1792, the ships entered the Straits of Juan de Fuca and anchored in the calm waters of Discovery Bay. Utilizing the bay as a base, Vancouver and his men explored the waters of Admiralty Inlet and Hood Canal.

Several weeks later, the Chetham began to sail north across the Straits of Juan de Fuca to explore the San Juan and Lopez Islands. After successfully doing so, the Chatham sailed southward in May to rejoin the HMS Discovery and continue their explorations south. The explorations continued as far as Commencement Bay in Tacoma, before turning around and returning north, where the waters were safer. Arriving at Puget Sound, they found a storm raging with severe currents and tides. Crossing an unknown channel, the Chatham was caught by a flood tide and swept helpless. To slow her progress, her stream anchor was dropped but the strain was too much and the cable snapped. However, the Chatham survived and after sweeping the waters unsuccessfully for the anchor, the ship rejoined the HMS Discovery.

Vancouver would write in his journal on June 9, 1792: “We found tides here extremely rapid, and on the 9th in endeavoring to get around a point to the Bellingham Bay we were swept leeward of it with great impetuosity. We let go the anchor in 20 fathoms but in bringing it up such was the force of the tide that we parted the cable. At slack water we swept for the anchor but could not get it. After several fruitless attempts, we were at last obliged to leave it.”

In 2008, an anchor was located off Whidbey Island’s northwestern shore. The anchor they found is believed to be the lost Chatham anchor, that was thought to be in Bellingham Bay. Anchor Ventures, LLC of Seattle salvaged the anchor, thought to be the one documented in mariners’ journals as breaking free from the

Chatham in heavy currents on June 9, 1792. Previous searches for the anchor had been focused in Bellingham Channel, where the main ship Discovery had been with high seas reported. The Chatham, a brig that was eventually captained by Peter Puget, was apparently not with the Discovery during the storm, the salvage team believes. The anchor was placed temporarily at the Northwest Maritime Center in downtown Port Townsend before being moved to Texas, where is was restored and is on display today.

Chatham in heavy currents on June 9, 1792. Previous searches for the anchor had been focused in Bellingham Channel, where the main ship Discovery had been with high seas reported. The Chatham, a brig that was eventually captained by Peter Puget, was apparently not with the Discovery during the storm, the salvage team believes. The anchor was placed temporarily at the Northwest Maritime Center in downtown Port Townsend before being moved to Texas, where is was restored and is on display today.

Weather has always been a subject of interest to people, even if we still don’t completely have a full grasp of it, not even after all these years and all our technology. The main difference I see now is that we hear about weather all the time. It’s on television, the radio, and even our phones. There are warnings for everything…thunder storms, tornadoes, snow storms, flash floods, and hurricanes. Nevertheless, all the meteorologists can truly do is predict a weather event. It may or may not materialize.

Weather has always been a subject of interest to people, even if we still don’t completely have a full grasp of it, not even after all these years and all our technology. The main difference I see now is that we hear about weather all the time. It’s on television, the radio, and even our phones. There are warnings for everything…thunder storms, tornadoes, snow storms, flash floods, and hurricanes. Nevertheless, all the meteorologists can truly do is predict a weather event. It may or may not materialize.

Now, flash back to, oh say 1680 or even to 1521. Other than looking at the sky, how did the people predict the weather? Yes the sky can be a great predictor of coming storms, but unless you knew something about weather  patterns, you would be unlikely to have any idea that something like a tornado, flood, or hurricane were coming. Especially in 1680 or 1521. Those dates are rather important in the world of weather. In August of 1521, a meteorological phenomenon occurred in the Basin of Mexico. There were no cameras back them, no cell phones or computers to record the event. The only known description appears in Book XII of the Florentine Codex, which is an account of the Spanish conquest of Mexico written in Nahuatl in the mid-sixteenth century. The account states that just before the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan a heavy storm which included a whirlwind struck the basin. The whirlwind hovered for a while above Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan’s twin city. Then it moved to the lake where it disappeared.

patterns, you would be unlikely to have any idea that something like a tornado, flood, or hurricane were coming. Especially in 1680 or 1521. Those dates are rather important in the world of weather. In August of 1521, a meteorological phenomenon occurred in the Basin of Mexico. There were no cameras back them, no cell phones or computers to record the event. The only known description appears in Book XII of the Florentine Codex, which is an account of the Spanish conquest of Mexico written in Nahuatl in the mid-sixteenth century. The account states that just before the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan a heavy storm which included a whirlwind struck the basin. The whirlwind hovered for a while above Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan’s twin city. Then it moved to the lake where it disappeared.

When the experts of today look at the account of the phenomenon in the context of the Nahua culture, and  comparing it with European descriptions of tornados and waterspouts, they can determine that the phenomenon was indeed a tornado. Their conclusion is further supported by eighteenth and nineteenth century pictorial and written evidence showing that tornadoes do occur in the territory now occupied by Mexico City. Since the tornado of Tlatelolco predates the Cambridge, Massachusetts, tornado of July 8, 1680, which had been thought to be the first recorded tornado in the Americas, the Tlatelolco tornado actually represents the earliest documented tornado in the Americas. Either way, since people didn’t really have much information to go on back then, I’m sure they first said some version of “What is that?!!?” At least, I know I would have.

comparing it with European descriptions of tornados and waterspouts, they can determine that the phenomenon was indeed a tornado. Their conclusion is further supported by eighteenth and nineteenth century pictorial and written evidence showing that tornadoes do occur in the territory now occupied by Mexico City. Since the tornado of Tlatelolco predates the Cambridge, Massachusetts, tornado of July 8, 1680, which had been thought to be the first recorded tornado in the Americas, the Tlatelolco tornado actually represents the earliest documented tornado in the Americas. Either way, since people didn’t really have much information to go on back then, I’m sure they first said some version of “What is that?!!?” At least, I know I would have.

My niece, Jenny Spethman is a woman of many talents. She is first and foremost a woman of God, who loves the Lord with all her heart. Life has not always been a bed of roses for Jenny, but through it all, she and her husband, Steve made God their center, and He has given then the strength to weather the storms that life brings…and some of these were hurricanes or tornadoes. Most weren’t literally that type, but they did fly through the edge of a hurricane on their way to their honeymoon, so they learned to trust God very early on in their marriage. The loss of their daughter, Laila at 22 days old, is something that would have ripped many a marriage apart, but not Jenny and Steve. They pressed into the Lord, and learned to seek His comfort in all the sad days that followed her passing. God has carried them through…every storm.

My niece, Jenny Spethman is a woman of many talents. She is first and foremost a woman of God, who loves the Lord with all her heart. Life has not always been a bed of roses for Jenny, but through it all, she and her husband, Steve made God their center, and He has given then the strength to weather the storms that life brings…and some of these were hurricanes or tornadoes. Most weren’t literally that type, but they did fly through the edge of a hurricane on their way to their honeymoon, so they learned to trust God very early on in their marriage. The loss of their daughter, Laila at 22 days old, is something that would have ripped many a marriage apart, but not Jenny and Steve. They pressed into the Lord, and learned to seek His comfort in all the sad days that followed her passing. God has carried them through…every storm.

Jenny loves being a wife and mother. Her family is her everything. She attends the boys, Xander, Zack, and Isaac’s sporting events, and her daughter, Aleesia’s girly events, like dancing, cheerleading. With the boys in school all day, Jenny and Aleesia have had more time to spend doing girly time. The sad thing is that now, Aleesia is almost ready for full time school too, so Jenny is in the process of deciding who she will be then. I have been in that situation too, so I understand how that feels. When you are no longer a full time caregiver, as in my case, or a full time mommy, as in Jenny’s case, you start to think, “Ok, then who am I?” It’s a question every mom has to answers at some point.

The reality is that everyone has these moments when they need to basically re-invent themselves. Jenny is trying to decide now, if she will go back to school or go to work. I totally understand the vast array of feelings she has about this. She will miss being the stay-at-home mom, with all the kids around her, but there is a type of excitement that comes with a new adventure, be it work or study. All new adventures are often bittersweet…exciting on the one side, but sad too, because you are leaving the time of your children’s babyhood behind. Bittersweet as it may be, I know that Jenny will weather this storm just fine too. Today is Jenny’s birthday. Happy birthday Jenny!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

![]() Yesterday, I heard the news that one of the iconic giant sequoia trees, located in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, is gone. The tree had been hollowed out to allow cars to drive through it. The Pioneer Cabin Tree, usually referred to as simply the “tunnel tree,” is estimated to be over 1,000 years old. It was knocked over by a powerful winter storm that slammed into California on Sunday. While the tunnel had been carved out of the tree, it was still very much a living tree.

Yesterday, I heard the news that one of the iconic giant sequoia trees, located in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, is gone. The tree had been hollowed out to allow cars to drive through it. The Pioneer Cabin Tree, usually referred to as simply the “tunnel tree,” is estimated to be over 1,000 years old. It was knocked over by a powerful winter storm that slammed into California on Sunday. While the tunnel had been carved out of the tree, it was still very much a living tree.

I immediately though back to a vacation my husband, Bob and I took a few years back, that took us through the scenic Redwood National Park in northern California. While the tree that we were able to drive through was not the one that was toppled in this storm, I still felt the loss of that amazing tree. The giant sequoia is the world’s largest tree, after all, and it is only found in the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It can reach a height of 325 feet. This particular tree, called the Pioneer Cabin Tree was actually hollowed out in about 1880. For a long time, cars drove through the iconic tree, but in recent years, it was only accessible by hiking trail. I thought about the tree we drove through, and how much fun it was to see such a huge tree. I was quite saddened by the loss of this beautiful tree.

Apparently, a volunteer, Jim Allday was in the park on Sunday when the tree came crashing down. It was about 2 pm, and the tree splintered on impact. The thing that he found most concerning was that visitors had been walking through the tree just hours earlier. He went out to the site to find the tree on the ground, and what ![]()

![]() looked like a pond or river running through it. The river was most likely the cause of the tree’s demise. The powerful winter storm brought heavy rain and snow to the area. It was the worst flooding in over a decade. The storm forced the closing of Yosemite National Park. It brought with it, hurricane-force winds of over 100 miles per hour. The wind and soggy ground were just too much for the giant tree. For people in the area, and anyone who has ever had the opportunity to see the tree and the park, it feels like losing a famous historical figure, and at 1,000, it was a great historical figure indeed.

looked like a pond or river running through it. The river was most likely the cause of the tree’s demise. The powerful winter storm brought heavy rain and snow to the area. It was the worst flooding in over a decade. The storm forced the closing of Yosemite National Park. It brought with it, hurricane-force winds of over 100 miles per hour. The wind and soggy ground were just too much for the giant tree. For people in the area, and anyone who has ever had the opportunity to see the tree and the park, it feels like losing a famous historical figure, and at 1,000, it was a great historical figure indeed.