siege

When my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Spencer, was serving in the Army Air Force during World War II, rationing was not an unusual thing. Nevertheless, most of us think of rationing to be in the form of gas rationing. That is pretty much the kind of rationing we have heard being used these days, but on January 8, 1941, the government of the United Kingdom began a different kind of rationing…food. I can see the value of such a thing, because by limiting the amount of food each person could have, they could ensure that everyone was able to get enough food to sustain them. People weren’t going to gain weight on the amount of food allowed, but they could survive. I suppose the fact that there were so many extra people, in the form of the military forces, just added to the need to ration.

When my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Spencer, was serving in the Army Air Force during World War II, rationing was not an unusual thing. Nevertheless, most of us think of rationing to be in the form of gas rationing. That is pretty much the kind of rationing we have heard being used these days, but on January 8, 1941, the government of the United Kingdom began a different kind of rationing…food. I can see the value of such a thing, because by limiting the amount of food each person could have, they could ensure that everyone was able to get enough food to sustain them. People weren’t going to gain weight on the amount of food allowed, but they could survive. I suppose the fact that there were so many extra people, in the form of the military forces, just added to the need to ration.

Of course, some food rationing occurred before this date too. Rationing was introduced temporarily by the government of the United Kingdom several times during the 20th century, during and immediately after a war. At the start of World War II in 1939, the United Kingdom was importing 20 million long tons of food per year, including about 70% of its cheese and sugar, almost 80% of its fruit and about 70% of its cereals and fats. It also imported more than half of its meat and relied on imported feed to support its domestic meat production. The civilian population of the country alone, was about 50 million. It was one of the principal strategies of the Germans in the Battle of the Atlantic to attack shipping bound for Britain, restricting British industry and  potentially starving nations into submission. Siege tactics were not unusual and have been used throughout history by several countries.

potentially starving nations into submission. Siege tactics were not unusual and have been used throughout history by several countries.

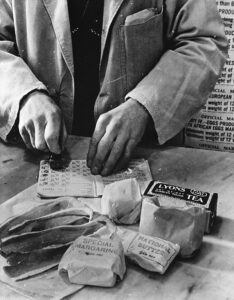

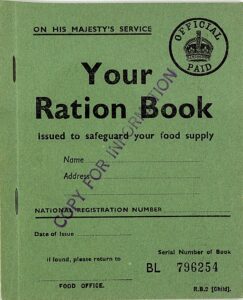

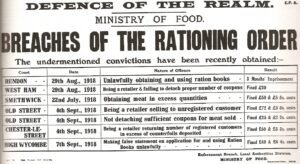

So, to deal with the various forms of shortages, and sometimes extreme shortages, the Ministry of Food instituted a system of rationing. Basically, the Ministry of Food would buy most rationed items, forcing anyone who wanted some of these items to register at chosen shops. Upon registration, they were provided with a ration book containing coupons. The shopkeeper was provided with enough food for registered customers. Purchasers had to present ration books when shopping so that the coupon or coupons could be cancelled as these pertained to rationed items. Rationed items had to be purchased and paid for as usual, although their price was strictly controlled by the government and many essential foodstuffs were subsidized. Basically, rationing restricted what items and what amount could be purchased, as well as what they would cost. To make matters worse the items that were not rationed could be scarce, because the Ministry of Food did not purchase said items. The priced for some of the unrationed items were also controlled by the Ministry of Food, and for many people those prices were too high for them to be able to afford, causing people to try to cheat the system, and merchants to try to either assist the people or to gouge the public in order to make a buck. This brought penalties for

breaking the laws of rationing.

breaking the laws of rationing.

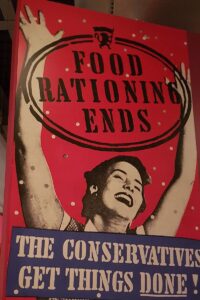

During the World War II, rationing was not restricted to food, and was part of a strategy including controlled prices, subsidies, and government-enforced standards. The goal for this controlled pricing and rationing was to manage scarcity and prioritize the armed forces and essential services with the supplies they needed first. They did still try to make available to everyone, an adequate and affordable supply of goods of acceptable quality. I suppose that how well they accomplished their goal, would be a matter of opinion. Of course, like all wars, World War II ended, as did the rationing of the time, but rationing has returned a number of times, and will again, should the need arise.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

Often when a robbery goes wrong, the would-be robbers decide that the best way out of the situation is to take hostages. The hope is to negotiate a way out of their pending imprisonment. Most hostage takings or sieges last a few hours but on September 28, 1975, The Spaghetti House siege began, and it continued until October 3, 1975. The Spaghetti House was a restaurant in Knightsbridge, London, and when the robbery went wrong, the police were on the scene so quickly that the robbers couldn’t get away. Seeing that they were trapped, the three robbers took the staff down into a storeroom and barricaded themselves in. The three robbers had been involved in black liberation organizations and tried to set the robbery as being politically motivated, thinking that a political standoff might have a better chance of success. The police did not believe them, however, and they stated that this was no more than a criminal act. Finally, they decided that the political ploy was not going to work, so the robbers released all the hostages unharmed after six days. I can’t say for sure that this was the longest robbery siege in history, but if it wasn’t, it ranked right up there. Finally, two of the gunmen gave themselves up, while the ringleader, Franklin Davies, shot himself in the stomach. He survived, and all three were later imprisoned, as were two accomplices. To keep tabs on the situation during the siege, the police used fiber optic camera technology, giving them live surveillance. They monitored the actions and conversations of the gunmen from the audio and visual output. They brought in a forensic psychiatrist to watch the feed and advise the police on the state of the men’s minds, and how to best manage the ongoing negotiations.

There were a number of things that potentially led up to the robbery, not that these things were in any way a good excuse. Post-World War II Britain had a shortage of labor. Due to that shortage, the British decided to bring in workers from the British Empire and Commonwealth countries. These people came from poverty areas,  and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

and while they were placed in low-pay, low-skill employment, which forced them to live in poor housing, it probably wasn’t much different than what they came from. Nevertheless, economic circumstances and what were seen by many in the black communities as racist policies applied by the British government, just like in other nations. This led to a rise in militancy, particularly among the West Indian community. The people grew angry, and their feelings were exacerbated by police harassment and discrimination in the education sector. The director of the Institute of Race Relations in the mid-1970s, Ambalavaner Sivanandan said that while the first generation had become partly assimilated into British society, the second generation were increasingly rebellious. These robbers were a part of that second generation.

The ringleader, Franklin Davies was a 28-year-old Nigerian student who had previously served time in prison for armed robbery. The two men with him were Wesley Dick (later known as Shujaa Moshesh), who was a 24-year-old West Indian; and Anthony “Bonsu” Munroe, a 22-year-old Guyanese. The men were all involved in black liberation organizations at one time or another. Davies had tried to enlist in the guerrilla armies of Zimbabwe African National Union and FRELIMO in Africa. While Munroe had links to the Black Power movement. Dick was an attendee at meetings of the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Front (BLF), the Fasimba, and the Black Unity and Freedom Party. He regularly visited the offices of the Institute of Race Relations to volunteer and access their library. Sivanandan and the historian Rob Waters identify that the three men were attempting to obtain money to “finance black supplementary schools and support African liberation struggles.”

By the mid-1970s the branch managers started a weekly tradition of closing the London-based Spaghetti House restaurant chain to meet at the company’s Knightsbridge branch. During that time, the outlet would be closed, but managers would deposit the week’s takings there, before it was paid into a night safe at a nearby bank. Of course, that was a well-known fact. So, at approximately 1:30am on Sunday, September 28, 1975, Davies, Moshesh, and Munroe entered the Knightsbridge branch of the Spaghetti House. One carried a sawed-off shotgun, and the others had handguns. The three men burst in and demanded the week’s takings from the chain, which was between £11,000 and £13,000. The restaurant was dimly lit, and it gave the staff a chance to  hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

hide the briefcases of money under the tables. Now infuriated, the three men forced the staff down into the back, but the company’s general manager managed to escape out the rear fire escape.

He quickly called the Metropolitan Police, who were at the scene within minutes. The getaway driver, Samuel Addison, realized that the plan was going wrong, so he decided that it was every man for himself, and drove off in a stolen Ford. The police entered the ground floor, so Davies and his colleagues forced the staff into a rear storeroom measuring 14 by 10 feet, locked the door, barricaded it with beer kegs. They began shouting at the police that they would shoot if they approached the door. The police surrounded the building, and the siege began. It would finally end on October 3, 1975, with the surrender of the robbers, and later the location and arrest of the two accomplices.

.

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

Tobruk began its existence as an ancient Greek colony, but later became a Roman fortress guarding the frontier of Cyrenaica. I suppose that qualifies as an important port. Tobruk became a waystation along the coastal caravan route, over the centuries. It became an Italian military post by 1911. Then, during World War II, Allied forces, mainly the Australian 6th Division, saw it a the perfect spot for a military base, and they took Tobruk on January 22, 1941. They reached Tobruk on April 9, 1941. At that time, there was prolonged fighting against German and Italian forces. Tobruk has a strong, naturally protected deep harbor. It is probably the best natural port in northern Africa. It wasn’t as popular, because it wasn’t near any landsites.

In 1941, Axis forces took over Tobruk, in a siege that would last for 241 days. The Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign of 1940–1943 in World War II. The Allies had defeated the Italian 10th Army during Operation Compass that took place between December 9, 1940 and February 9, 1941, and trapped the remnants of the troops at Beda Fomm. Much of the Western Desert Force (WDF) was sent to the Greek and Syrian campaign in early 1941. By the time German troops and Italian reinforcements reached Libya, only a skeleton Allied force remained, and they were short of equipment and supplies. It was then that the Australian 9th Division became known as “The Rats of Tobruk” when they pulled back to Tobruk to avoid encirclement after actions at Er

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.

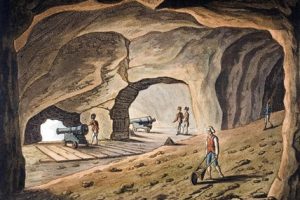

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

The tunnels of Gibraltar were constructed over the course of nearly 200 years, principally by the British Army. Within a land area of only 2.6 square miles, Gibraltar has around 34 miles of tunnels, nearly twice the length of its entire road network. The first tunnels were excavated in the late 18th century. They served as communication passages between artillery positions and housed guns within embrasures cut into the North Face of the Rock, to protect the interior city. More tunnels were constructed in the 19th century to allow easier access to remote areas of Gibraltar and accommodate stores and reservoirs to deliver the water supply of

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

It was to this place that the French Resistance smuggled downed Allied airmen and other escapees from the Nazi regime inside France. Men like Staff Sergeant Arthur Meyerowitz and RAF Bomber Lieutenant R.F.W. Cleaver…two of the men who were smuggled out of occupied France by the French Resistance network known as Réseau Morhange which was created in 1943 by Marcel Taillandier in Toulouse. Taillandier was killed shortly after these two men were smuggled out. He had given his life to protect the airmen he smuggled out as well as to provide intelligence to England. For the airmen who made it to the Rock of Gibraltar, freedom awaited. While

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

In 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. From that time forward until 1920, all of Ireland was a part of the British Isles. The British Isles is a geographical term which includes two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and 5,000 small islands, most notably the Isle of Man which has its own parliament and laws. Today, only Northern Ireland remains, as part of the United Kingdom.

In 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. From that time forward until 1920, all of Ireland was a part of the British Isles. The British Isles is a geographical term which includes two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and 5,000 small islands, most notably the Isle of Man which has its own parliament and laws. Today, only Northern Ireland remains, as part of the United Kingdom.

For the most part, the Irish War of Independence, also called the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla conflict and most of the fighting was conducted on a small scale by the standards of conventional warfare. Although there were some large-scale encounters between the Irish Republican Army and the state forces of the United Kingdom. The Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC), generally known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, was a paramilitary unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the War. It was set up in July 1920 and made up of former British Army officers, most of whom came from Great Britain. Its role was to conduct counter-insurgency operations against  the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Auxiliaries became infamous for their reprisals on civilians and civilian property in revenge for IRA actions, the best known example of which was the burning of Cork city in December 1920. The Black and Tans officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was a force of temporary constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the war. The force was the brainchild of Winston Churchill, then British Secretary of State for War. Recruitment began in Great Britain in late 1919. Thousands of men, many of them British Army veterans of World War I, answered the British government’s call for recruits.

the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Auxiliaries became infamous for their reprisals on civilians and civilian property in revenge for IRA actions, the best known example of which was the burning of Cork city in December 1920. The Black and Tans officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was a force of temporary constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the war. The force was the brainchild of Winston Churchill, then British Secretary of State for War. Recruitment began in Great Britain in late 1919. Thousands of men, many of them British Army veterans of World War I, answered the British government’s call for recruits.

The war continued on and by November 1920, around 300 people had been killed in the conflict. Then, there  was an escalation of violence beginning on Bloody Sunday, November 21, 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated in Dublin in the morning. Then, in retaliation, the afternoon the RIC opened fire on a crowd at a Gaelic football match in the city, killing fourteen civilians and wounding 65. A week later, seventeen Auxiliaries were killed by the IRA in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In retaliation, the British government declared martial law in much of southern Ireland. The centre of Cork City was burnt out by British forces on December 10, 1920. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months, when 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths. Violence in Ulster, especially Belfast, was notable for its sectarian character and its high number of Catholic civilians.

was an escalation of violence beginning on Bloody Sunday, November 21, 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated in Dublin in the morning. Then, in retaliation, the afternoon the RIC opened fire on a crowd at a Gaelic football match in the city, killing fourteen civilians and wounding 65. A week later, seventeen Auxiliaries were killed by the IRA in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In retaliation, the British government declared martial law in much of southern Ireland. The centre of Cork City was burnt out by British forces on December 10, 1920. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months, when 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths. Violence in Ulster, especially Belfast, was notable for its sectarian character and its high number of Catholic civilians.

During World War II, many children lost their parents to hunger or bombings. Many of the orphanages were either overcrowded or non-existent. To save them from starvation, many Russian military units adopted the orphans. I’m not sure what the units did with the children while they were fighting, but my guess is that some of them wrote home to their wives and told them that they wanted to adopt these little cuties.

During World War II, many children lost their parents to hunger or bombings. Many of the orphanages were either overcrowded or non-existent. To save them from starvation, many Russian military units adopted the orphans. I’m not sure what the units did with the children while they were fighting, but my guess is that some of them wrote home to their wives and told them that they wanted to adopt these little cuties.

Two year old Lucy was adopted by Russian sailors of the Baltic Fleet after her parents died during the siege of Leningrad. Of course, she was too young to really remember her parents, and so whoever ended up adopting her would become her parents in her mind. Little is known about what happened to Lucy after this picture was taken, but if she is still alive, she would be in her mid-seventies now.

Of course, not all children were as blessed to find homes. One orphaned boy who had to live in a foster home wrote in a small notebook about how many of his friends were dying of hunger, and at the same time he drew “amazing” images of food such as “ham and chicken” in the pages of his diary. I guess he was trying to remind himself about the good old days…when food was abundant and his parents were still alive.

People who were living in Leningrad during the siege went through the worst of times. In all, the siege lasted 900 days (almost 2½ years). Food was scarce, and the people withered away. They could not escape and they could not bring in supplies. Eventually, people began to die. In all, more than a million civilians died during those horrible days. Lucy’s parents were among those who didn’t make it, probably because they gave what  little food they had to her. I can’t imagine what must have gone through their minds. They must have agonized over the instinct to do whatever it took to keep their child alive, and wondering what would happen to her if they died and left her orphaned.

little food they had to her. I can’t imagine what must have gone through their minds. They must have agonized over the instinct to do whatever it took to keep their child alive, and wondering what would happen to her if they died and left her orphaned.

I wish there was a way to find out what happened to Lucy. I hope she had a good life with loving parents, who gave her the kind of life her own parents would have given her, had they lived. I hope she grew up to have a husband and children of her own. And I hope that her adoptive parents told her about the parents who loved her so much that they allowed themselves to starve to death, that she might live. Such a sacrifice should not go unnoticed, nor should it ever be forgotten.

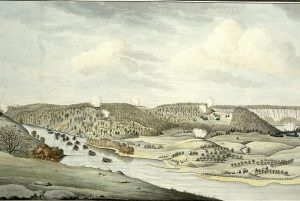

When one side of a war takes control of an area or a fort belonging to the other side, they often change the name of the area or fort to reflect the name of the hero who laid siege on it. Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen became a British hero in 1776, when he and a force of 3,000 Hessian mercenaries and 5,000 Redcoats laid siege to Fort Washington at the northern end and highest point of Manhattan Island on November 16, 1776.

When one side of a war takes control of an area or a fort belonging to the other side, they often change the name of the area or fort to reflect the name of the hero who laid siege on it. Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen became a British hero in 1776, when he and a force of 3,000 Hessian mercenaries and 5,000 Redcoats laid siege to Fort Washington at the northern end and highest point of Manhattan Island on November 16, 1776.

Throughout that morning, Knyphausen met stiff resistance from the Patriot riflemen inside, but by afternoon, the Patriots were overwhelmed, and the garrison commander, Colonel Robert Magaw, surrendered. Nearly 3,000 Patriots were taken prisoner, and valuable ammunition and supplies were lost to the Hessians. The prisoners faced a particularly grim fate, because many later died aboard British prison ships anchored in New York Harbor. Among the 53 dead and 96 wounded Patriots were John and Margaret Corbin of Virginia. When John died in action, his wife Margaret took over his cannon, cleaning, loading, and firing the gun until she too was severely wounded. The first woman known to have fought for the Continental Army, Margaret survived, but lost the use of her left arm. Margaret Cochran (Corbin) was born in Western Pennsylvania on November 12, 1751 in what is now Franklin County. Her parents were Robert Cochran, a Scots-Irish immigrant, and his wife, Sarah. In 1756, when Margaret was five years old, her parents were attacked by Native Americans. Her father was killed, and her mother was kidnapped, never to be seen again.

Margaret and her brother, John escaped the raid because they were not at home. They lived with their uncle for the rest of their childhood. Margaret became a survivor…not a victim, and I’m sure that was why she picked up where her husband left off and fought as well as any man there.

Margaret and her brother, John escaped the raid because they were not at home. They lived with their uncle for the rest of their childhood. Margaret became a survivor…not a victim, and I’m sure that was why she picked up where her husband left off and fought as well as any man there.

While Margaret, her husband, John, and many others showed great heroics in the attack, not everyone involved in Magaw’s army, were heroes. Two weeks earlier, one of Magaw’s officers, William Demont, had deserted the Fifth Pennsylvania Battalion and given British intelligence agents information about the Patriot defense of New York, including details about the location and defense of Fort Washington. Demont was the first traitor to the Patriot cause, and his treason contributed significantly to Knyphausen’s victory. What a vast difference there was between this horrible, traitorous man and the very brave Margaret Corbin!!

After the siege, and in honor of Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, who had stormed the post five days earlier, British Commander in Chief General William Howe renamed Fort Washington, “Fort Knyphausen” on November 17, 1776. It was a devastating loss to the patriots. Today, the site of Fort Washington is Bennett Park on Fort Washington Avenue, between West 183rd and West 185th streets in the neighborhood of the  Washington Heights section of New York City. The locations of the fort’s walls are marked in the park by stones, along with a tablet commemorating the location of Fort Washington, and the brave troops who took back the fort on their triumphal entry into the city of New York on November 25, 1783. Nearby is a tablet indicating that the schist outcropping is the highest natural point on Manhattan Island, one of the reasons for the fort’s location. Bennett Park is located a few blocks north of the George Washington Bridge. Along the banks of the Hudson River below the Henry Hudson Parkway is Fort Washington Park and the small point of land alternately called Jeffrey’s Hook or Fort Washington Point, which is the site of the Little Red Lighthouse.

Washington Heights section of New York City. The locations of the fort’s walls are marked in the park by stones, along with a tablet commemorating the location of Fort Washington, and the brave troops who took back the fort on their triumphal entry into the city of New York on November 25, 1783. Nearby is a tablet indicating that the schist outcropping is the highest natural point on Manhattan Island, one of the reasons for the fort’s location. Bennett Park is located a few blocks north of the George Washington Bridge. Along the banks of the Hudson River below the Henry Hudson Parkway is Fort Washington Park and the small point of land alternately called Jeffrey’s Hook or Fort Washington Point, which is the site of the Little Red Lighthouse.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

The German and Finnish forces besieged Lenin’s namesake city after their spectacular initial advance during Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941. Nevertheless, it was not going to be an easy task to bring the Soviet people into submission. A German Army Group struggled against stubborn Soviet resistance to isolate and seize the city before the onset of winter. The fighting was heaviest during August. German forces reached the city’s suburbs and the shores of Lake Ladoga, severing Soviet ground communications with the city. In  November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

After November 1941, possession of Leningrad held only symbolic significance. In holding the “ice and water road” the Soviets were able to bring in enough supplies to stave of the ongoing starvation, so the siege has a  little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.

little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.