ships

Most of us have heard the name Sandy Hook because of the school shooting that took place in an elementary school with the same name in Newtown, Connecticut. That tragedy was not the first time the name Sandy Hook had been at the center of attention, however. Most people know that along United States coastal areas, there are many lighthouses. The lighthouses might not be so necessary these days, because of GPS tracking, but before all of the technology that we have today, lighthouses were the only way for a ship to know if they were coming dangerously close to a stretch of land. Such was the case with the Sandy Hook lighthouse in 1776. The problem they were having with the lighthouse, however, is that it was thought that the lighthouse would also help the British ships to invade New York City. It was a very real concern, and posed a grave danger to the Provincial Congress of New York.

Most of us have heard the name Sandy Hook because of the school shooting that took place in an elementary school with the same name in Newtown, Connecticut. That tragedy was not the first time the name Sandy Hook had been at the center of attention, however. Most people know that along United States coastal areas, there are many lighthouses. The lighthouses might not be so necessary these days, because of GPS tracking, but before all of the technology that we have today, lighthouses were the only way for a ship to know if they were coming dangerously close to a stretch of land. Such was the case with the Sandy Hook lighthouse in 1776. The problem they were having with the lighthouse, however, is that it was thought that the lighthouse would also help the British ships to invade New York City. It was a very real concern, and posed a grave danger to the Provincial Congress of New York.

The Sandy Hook lighthouse was located on a piece of land that was disputed territory in those days. The land sits directly across the bay from New York City, making it an important shipping lane, but a dangerous one too. In early 1761, the Provincial Congress of New York set up lotteries to raise money for the construction of a lighthouse. A lighthouse in this area had been under discussion for nearly a century before it was initiated by Colonial Governor Edmund Andread. Forty three New York merchants proposed the lotteries to the Provincial Council, after losing 20,000 sterling pounds to shipwrecks in 1761. The money was collected, and the Sandy Hook lighthouse was built. It first shone its beam on June 11, 1764. It served it’s purpose quite well…in fact maybe too well…at least during the Revolutionary War. Ships weren’t sinking, but in a big way, it left New York City quite vulnerable to attack. So, after just fifteen years of use, the New York Provincial Congress decided that the lighthouse had to be dismantled. Then came the controversy. A committee of the New York Provincial Congress told Major William Malcolm to “use your best discretion to render the light-house entirely useless.” They wanted him to remove the lens and lamps so that the lighthouse could no longer warn ships of possible hazards on the rocky shore. He succeeded. Colonel George Taylor reported to the committee six days later, that Malcolm had given him eight copper lamps, two tackle falls and blocks, three casks, and a part of a cast of oil from the dismantling of the beacon.

Malcolm’s efforts failed, because the lighthouse was quickly put back into service by the merchants in the area, with the installation of lamps and reflectors. The Patriots attempted to knock the light out again on June 1st, by placing cannon on boats and attempting to blow away the British paraphernalia, damaging some of it before

they were chased away. Malcolm’s efforts did not prevent the British from invading New York City. The new states of New York and New Jersey fought over ownership of the lighthouse until the federal government assumed control of all US lighthouses in 1787. As of 1996, the Sandy Hook lighthouse, the oldest original lighthouse in the United States, became a historic landmark, and passed into the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. It is still in operation as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

they were chased away. Malcolm’s efforts did not prevent the British from invading New York City. The new states of New York and New Jersey fought over ownership of the lighthouse until the federal government assumed control of all US lighthouses in 1787. As of 1996, the Sandy Hook lighthouse, the oldest original lighthouse in the United States, became a historic landmark, and passed into the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. It is still in operation as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

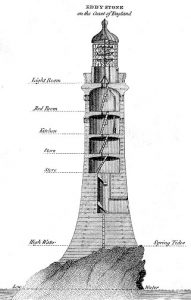

As lighthouses go, Eddystone lighthouse is really quite different than most. The first Eddystone lighthouse was completed in 1699, and was the world’s first open ocean lighthouse, although the Cordouan lighthouse preceded it as the first offshore lighthouse. The Eddystone Lighthouse is on the dangerous Eddystone Rocks, 9 statute miles south of Rame Head, England, United Kingdom. While Rame Head is in Cornwall, the rocks are in Devon. Putting a lighthouse in the open ocean was a rather dangerous undertaking, but it was also an important lighthouse, because of the rocks it sat on. Without a lighthouse there, ships would run aground on the rocks.

As lighthouses go, Eddystone lighthouse is really quite different than most. The first Eddystone lighthouse was completed in 1699, and was the world’s first open ocean lighthouse, although the Cordouan lighthouse preceded it as the first offshore lighthouse. The Eddystone Lighthouse is on the dangerous Eddystone Rocks, 9 statute miles south of Rame Head, England, United Kingdom. While Rame Head is in Cornwall, the rocks are in Devon. Putting a lighthouse in the open ocean was a rather dangerous undertaking, but it was also an important lighthouse, because of the rocks it sat on. Without a lighthouse there, ships would run aground on the rocks.

The Eddystone lighthouse fell to disaster three times, and was rebuilt threes times. The first disaster came just four years later, when the Great Storm of 1703 took with it, the first Eddystone lighthouse. The first and second lighthouses were constructed of wood. This was the material available at the time. It was also the wooden construction that made the lighthouse susceptible to the distructive storm and the fire that destroyed the first and second lighthouses…the storm in 1703 and the fire in 1755. The third lighthouse is often called Smeaton’s lighthouse. It was recommended by the Royal Society, civil engineer John Smeaton and was modeled in the shape on an oak tree, and built of granite blocks. He pioneered hydraulic lime, a concrete that cured under water, and developed a technique of securing the granite blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Construction started in 1756 at Millbay and the light was first lit on October 16, 1759. It was state of the art in

its time. It stood until 1877, when the rocks eroded enough to cause the lighthouse to rock from side to side in the waves, so it was deemed unsafe. The fourth and current lighthouse was built in April of 1879, and was designed by James Douglass, using Robert Stevenson’s developments of Smeaton’s techniques. By April 1879 the new site, on the South Rock was being prepared during the 3½ hours between ebb and flood tide. This current lighthouse is shorter and has a flat top, that is used to land helicopters.

its time. It stood until 1877, when the rocks eroded enough to cause the lighthouse to rock from side to side in the waves, so it was deemed unsafe. The fourth and current lighthouse was built in April of 1879, and was designed by James Douglass, using Robert Stevenson’s developments of Smeaton’s techniques. By April 1879 the new site, on the South Rock was being prepared during the 3½ hours between ebb and flood tide. This current lighthouse is shorter and has a flat top, that is used to land helicopters.

Back in the 1700s, there were no early warning systems for storms, and I suppose it wouldn’t matter anyway, at least not when it came to the Great Storm of 1703. The storm was a destructive extratropical cyclone that struck central and southern England on November 26, 1703, which would actually have been December 7, by today’s calendar. You see the dates all changed with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which was originally developed in 1582, but not adopted by England until 1752. The storm brought with it high winds topping 80 miles per hour, which may not seem so extreme on dry land, but over water, it’s devastating. In fact, the wind was so bad, that it actually blew 2,000 chimney stacks over in London. It also blew over 4,000 oak trees down in New Forest. The winds blew ships hundreds of miles off course, and over 1,000 seamen lost their lives on the Goodwin Sands alone.

Back in the 1700s, there were no early warning systems for storms, and I suppose it wouldn’t matter anyway, at least not when it came to the Great Storm of 1703. The storm was a destructive extratropical cyclone that struck central and southern England on November 26, 1703, which would actually have been December 7, by today’s calendar. You see the dates all changed with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which was originally developed in 1582, but not adopted by England until 1752. The storm brought with it high winds topping 80 miles per hour, which may not seem so extreme on dry land, but over water, it’s devastating. In fact, the wind was so bad, that it actually blew 2,000 chimney stacks over in London. It also blew over 4,000 oak trees down in New Forest. The winds blew ships hundreds of miles off course, and over 1,000 seamen lost their lives on the Goodwin Sands alone.

London suffered extensive damage. The lead roofing was blown off Westminster Abbey and Queen Anne had to seek shelter in a cellar at Saint James’s Palace to avoid collapsing chimneys and part of the roof. About 700 ships were heaped together in the Pool of London, which is the section of the Thames River downstream from the London Bridge. The ship HMS Vanguard was wrecked at Chatham. Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s HMS Association was blown from Harwich to Gothenburg in Sweden before it could make its way back to England. Pinnacles were blown from the top of King’s College Chapel, in Cambridge. At sea, many ships were wrecked, some of which were returning from helping Archduke Charles, the claimed King of Spain, fight the French in the War of the Spanish Succession. These ships included HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Northumberland, HMS Mary and HMS Restoration, with about 1,500 seamen killed particularly on the Goodwin Sands. Between 8,000 and 15,000 lives were lost overall.

The Church of England declared that the vicious storm was God’s vengeance for the sins of the nation. Maybe this is where the

rediculous saying, “act of God” was coined. In fact, Daniel Defoe thought it was a divine punishment for poor performance against Catholic armies in the War of the Spanish Succession. That makes the whole statement even more ridiculous. I suppose people have to explain away these wild occurrences somehow, and since they didn’t have the science to explain the storm, they blamed God for it.

rediculous saying, “act of God” was coined. In fact, Daniel Defoe thought it was a divine punishment for poor performance against Catholic armies in the War of the Spanish Succession. That makes the whole statement even more ridiculous. I suppose people have to explain away these wild occurrences somehow, and since they didn’t have the science to explain the storm, they blamed God for it.

Over the centuries, many ships have been lost at sea, but it isn’t every day that 33 ships are lost together. That was the case in September of 1871, however, when the ice off of the coast of Alaska trapped 33 out of 40 commercial whaling ships who were hunting for bowhead whales in the Artic Ocean. Normally, when ice traps a ship, it eventually releases it’s grip with the shifting winds, but in this case that didn’t happen, and the results were disastrous. Within a few weeks, the ships were destroyed, and the families and crew members had to evacuate and head for one of the ships that was not trapped. As the 1,219 additional people boarded the remaining 7 ships, those ships became overloaded. They had to throw things overboard to allow for the extra weight. Things like their equipment and their precious cargo were lost. The already struggling whaling industry in the United States was basically dealt a final blow. The amazing thing was that no one died, but the loss of 33 ships over those weeks was devastating enough to the whaling industry.

Over the centuries, many ships have been lost at sea, but it isn’t every day that 33 ships are lost together. That was the case in September of 1871, however, when the ice off of the coast of Alaska trapped 33 out of 40 commercial whaling ships who were hunting for bowhead whales in the Artic Ocean. Normally, when ice traps a ship, it eventually releases it’s grip with the shifting winds, but in this case that didn’t happen, and the results were disastrous. Within a few weeks, the ships were destroyed, and the families and crew members had to evacuate and head for one of the ships that was not trapped. As the 1,219 additional people boarded the remaining 7 ships, those ships became overloaded. They had to throw things overboard to allow for the extra weight. Things like their equipment and their precious cargo were lost. The already struggling whaling industry in the United States was basically dealt a final blow. The amazing thing was that no one died, but the loss of 33 ships over those weeks was devastating enough to the whaling industry.

Not much was found of the ships for many years, although debris washed up on shore periodically. Still, no artifacts specifically tied to the shipwrecks could be found beneath beneath the water. In 2015, thanks to technological advances, archaeologists have found the wreckage of what appears to be two of the lost ships. They are located at the bottom of the Chukchi Sea off the coast of Wainwright, Alaska, but an exact location is not being given. Brad Barr, an archaeologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), estimated the losses caused by what has been dubbed the Great Whaling Disaster of 1871 would have reached the equivalent of a little more than $33 million today. As Barr told LiveScience: “The event has been attributed as possibly a major contributory factor in the demise of whaling in the U.S.”

Barr began his hunt in late August 2015. He and a team of researchers from the Maritime Heritage Program of the NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries surveyed the floor of the Chukchi Sea off the coast of the Inupiat village of Wainwright, in northwestern Alaska. They used state of the art sonar and underwater sensing technologies. They found the magnetic signatures of two shipwrecks they believe are part of the lost 1871 fleet, including the outlines of their flattened hulls. Underwater video revealed anchors, fasteners, pins, and ballast. They even discovered some of the special brick lined pots that the whalers used to heat the whale blubber to turn it into whale oil that was used to fire up oil lamps and make soap, margarine, and other products before the advent of petroleum. While the scientists can’t say definitively that the two wrecked ships were among the 33 lost in 1871, there are a lot of signs that point to it. More than half of all the ships known to have wrecked in the area went down in the 1871 event, and both wrecks, their beams and hull timbers were similar to those used in whaling ships from the late 19th century. The team was also aided in their efforts by changing sea ice levels, increasing opportunities to uncover lost shipwrecks even off Alaska’s northern coast. During the  expedition to the Chukchi Sea, the absence of ice was notable, and the archaeologists reportedly found artifacts from the wrecked ships “just sitting there” for them to find, Barr’s said. The team discovered remnants of a sandbar, which they believe protected the artifacts from sea ice. The NOAA is not really worried that the historic site will be disturbed, because historic preservation laws still apply. Also, there is no gold bullion, jewels or other precious cargo that might draw fortune hunters. Nevertheless, they are not publicizing the site’s exact location. Instead, they will provide all information to the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology, the agency in charge of protecting sites and relics in Alaska.

expedition to the Chukchi Sea, the absence of ice was notable, and the archaeologists reportedly found artifacts from the wrecked ships “just sitting there” for them to find, Barr’s said. The team discovered remnants of a sandbar, which they believe protected the artifacts from sea ice. The NOAA is not really worried that the historic site will be disturbed, because historic preservation laws still apply. Also, there is no gold bullion, jewels or other precious cargo that might draw fortune hunters. Nevertheless, they are not publicizing the site’s exact location. Instead, they will provide all information to the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology, the agency in charge of protecting sites and relics in Alaska.

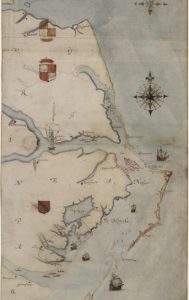

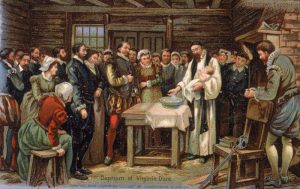

When I think of a lost people, I think of a tribe in Africa or somewhere very isolated, but I never think of someplace in America! Nevertheless, it happened right here in America. Of course, it was a long…long time ago. It was long before people could easily track someone down. The year was 1587, the day was July 22. That was the day when the new colony arrived in Roanoke, North Carolina, which was colonial Virginia. On August 18, 1587, the first English baby to be born in the Americas, Virginia Dare was born. The group had been dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh, and was led by John White, who by the way, was Virginia Dare’s grandfather. Upon their arrival, they found nothing of the English garrison that had gone ahead, except one skeleton. The people really didn’t want to stay there after that, but the fleet commander, Simon Fernandez would not let them return to the ship, and the ships sailed with the promise of new supplies to come.

When I think of a lost people, I think of a tribe in Africa or somewhere very isolated, but I never think of someplace in America! Nevertheless, it happened right here in America. Of course, it was a long…long time ago. It was long before people could easily track someone down. The year was 1587, the day was July 22. That was the day when the new colony arrived in Roanoke, North Carolina, which was colonial Virginia. On August 18, 1587, the first English baby to be born in the Americas, Virginia Dare was born. The group had been dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh, and was led by John White, who by the way, was Virginia Dare’s grandfather. Upon their arrival, they found nothing of the English garrison that had gone ahead, except one skeleton. The people really didn’t want to stay there after that, but the fleet commander, Simon Fernandez would not let them return to the ship, and the ships sailed with the promise of new supplies to come.

John White was not allowed to stay, and so returned to England on August 27, 1587…vowing to return in three months time. That was about the time of the Spanish Armada attack in 1588, which delayed White’s return to Roanoke. White tried desperately to return to the little colony for the next three years. When he was finally able to get there, he came rushing onshore, only to find that the colony was gone.

Among those missing was the little girl, Virginia Dare, White’s granddaughter. They had arrived on what would have been her third birthday…August 15. Whites return was delayed because of the Anglo-Spanish war, and the Spanish ships that robbed the expedition of the supplies they were taking over to the colonists. It is suspected that the colony disappeared during that war, but there is no clear clarification as to where they went or who took them.

Among those missing was the little girl, Virginia Dare, White’s granddaughter. They had arrived on what would have been her third birthday…August 15. Whites return was delayed because of the Anglo-Spanish war, and the Spanish ships that robbed the expedition of the supplies they were taking over to the colonists. It is suspected that the colony disappeared during that war, but there is no clear clarification as to where they went or who took them.

There has been much speculation as to the fate of the Roanoke Lost Colony, but the sure fate of the settlers left behind is unknown and the colony is known as the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke to this day. Over the years numerous attempts have been made to find the Lost Colony, including the Lost Colony DNA Project started in 2005. Recent investigations speculate that the Lost Colony relocated to where the Chowan River meets the Albemarle Sound in present day Bertie County, North Carolina. Nevertheless, recent discoveries found  European objects in the Hatteras Island area, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls, and a fragment of a slate writing tablet still inscribed with a letter. These could point to the presence of the colonists on Hatteras Island, some 50 miles southeast of their settlement on Roanoke Island. There were also some found at a site on the mainland 50 miles to the northwest. Some people have thought that the Native Americans took the people or at least assimilated them into their tribe, because there are in some of that modern day tribe of people with strangely gray eyes. I suppose we will never really know the reality of what happened, but I would rather think that the Native Americans took them in, than to think that they were killed.

European objects in the Hatteras Island area, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls, and a fragment of a slate writing tablet still inscribed with a letter. These could point to the presence of the colonists on Hatteras Island, some 50 miles southeast of their settlement on Roanoke Island. There were also some found at a site on the mainland 50 miles to the northwest. Some people have thought that the Native Americans took the people or at least assimilated them into their tribe, because there are in some of that modern day tribe of people with strangely gray eyes. I suppose we will never really know the reality of what happened, but I would rather think that the Native Americans took them in, than to think that they were killed.

Because I was born in Superior, Wisconsin, located at the tip of Lake Superior, and across the bridge from Duluth, Minnesota, I am interested in all things that have to do with that area. My family moved to Casper, Wyoming when I was three, so I was not raised in that area, but somehow, it is in my blood. I will always have roots I can feel there. We still have a large number of family members there, and we continue to get to know them more and more due to a trip back there, and continued connections on Facebook. For that family we are very grateful, because they are all amazing.

Because I was born in Superior, Wisconsin, located at the tip of Lake Superior, and across the bridge from Duluth, Minnesota, I am interested in all things that have to do with that area. My family moved to Casper, Wyoming when I was three, so I was not raised in that area, but somehow, it is in my blood. I will always have roots I can feel there. We still have a large number of family members there, and we continue to get to know them more and more due to a trip back there, and continued connections on Facebook. For that family we are very grateful, because they are all amazing.

As I said, I love the area around Lake Superior, and the shipping business that comes through there is an amazing thing to watch. In order for shipping to thrive on Lake Superior, they had to have a way to get the big oar boats and other large ships into the port. In 1892, a contest was held to find a solution for the transportation needs to go from Minnesota Point to the other side of the canal that was dug in 1871. a man named John Low Waddell came up with the winning design for a high rise vertical lift bridge. The city of Duluth was eager to build the bridge, but the War Department didn’t like the design, and so the project was cancelled before it started. It really was an unfortunate mistake.

Later, new plans were drawn up for a structure that would ferry people from one side to the other. This one was designed by Thomas McGilvray, a city engineer. That structure was finished in 1905. The gondola had a capacity of 60 tons and was able to carry 350 people, plus wagons, streetcars, and automobiles. The trip across took about a minutes and the ferry crossed once every five minutes, but as the population grew, the demand for a better way across grew too. They would have to rethink the situation, and amazingly, he firm finally commissioned with designing the new bridge was the descendant of Waddell’s company…the original design winner. The new design, which closely resembles the 1892 concept, is attributed to C.A.P. Turner. I guess they should have used that design in the first place, and it might have saved a lot of money.

Later, new plans were drawn up for a structure that would ferry people from one side to the other. This one was designed by Thomas McGilvray, a city engineer. That structure was finished in 1905. The gondola had a capacity of 60 tons and was able to carry 350 people, plus wagons, streetcars, and automobiles. The trip across took about a minutes and the ferry crossed once every five minutes, but as the population grew, the demand for a better way across grew too. They would have to rethink the situation, and amazingly, he firm finally commissioned with designing the new bridge was the descendant of Waddell’s company…the original design winner. The new design, which closely resembles the 1892 concept, is attributed to C.A.P. Turner. I guess they should have used that design in the first place, and it might have saved a lot of money.

Construction began in 1929. They knew that they had to be able to accommodate the tall ships that would pass through. In the new design, the roadway simply lifted in the middle, and after the ship went through it lowered  again, becoming a bridge for cars. The design is amazing, and grabs the attention of thousands of people on a regular basis. The new bridge first lifted for a vessel on March 29, 1930. Raising the bridge to its full height of 135 feet takes about a minute. The bridge is raised approximately 5,000 times per year. The bridge span is about 390 feet. As ships pass, there is a customary horn blowing sequence that is copied back. The bridge’s “horn” is actually made up of two Westinghouse Airbrake locomotive horns. Long-short-long-short means to raise the bridge, and Long-short-short is a friendly salute. The onlookers love it, and the crews often wave as well. It is like a parade of ships on a daily basis, and probably the reason that the bridge is so often the subject of pictures of the area. Happy 86th Anniversary to the Duluth Lift Bridge.

again, becoming a bridge for cars. The design is amazing, and grabs the attention of thousands of people on a regular basis. The new bridge first lifted for a vessel on March 29, 1930. Raising the bridge to its full height of 135 feet takes about a minute. The bridge is raised approximately 5,000 times per year. The bridge span is about 390 feet. As ships pass, there is a customary horn blowing sequence that is copied back. The bridge’s “horn” is actually made up of two Westinghouse Airbrake locomotive horns. Long-short-long-short means to raise the bridge, and Long-short-short is a friendly salute. The onlookers love it, and the crews often wave as well. It is like a parade of ships on a daily basis, and probably the reason that the bridge is so often the subject of pictures of the area. Happy 86th Anniversary to the Duluth Lift Bridge.

Any time ammunition, explosives, and bombs are being stored in a smaller space, and handled by multiple people, there is a possibility of disaster. The USS Mount Hood was the lead ship of her class of ammunition ships for the United States Navy in World War II. Her life was short lived. The North Carolina Shipbuilding Company began work on the ship on September 28, 1943, and the intended name of the ship was SS Marco Polo. It was first launched on November 28, 1943, and aquired by the Navy on January 28, 1944. It was commissioned the USS Mount Hood on July 1, 1944. The ship was named after Mount Hood, the volcano in the Cascade Range in Oregon.

Any time ammunition, explosives, and bombs are being stored in a smaller space, and handled by multiple people, there is a possibility of disaster. The USS Mount Hood was the lead ship of her class of ammunition ships for the United States Navy in World War II. Her life was short lived. The North Carolina Shipbuilding Company began work on the ship on September 28, 1943, and the intended name of the ship was SS Marco Polo. It was first launched on November 28, 1943, and aquired by the Navy on January 28, 1944. It was commissioned the USS Mount Hood on July 1, 1944. The ship was named after Mount Hood, the volcano in the Cascade Range in Oregon.

Following a short fitting out and shakedown period in the Chesapeake Bay area, the USS Mount Hood reported for duty to ComServFor, Atlantic Fleet on August 5, 1944. She was assigned to carry cargo to the Pacific, and she pulled in to Norfolk, where her holds were loaded. The she was transfered to the Panama Canal as part of  Task Group 29.6. She finally ended up Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island of the Admiralty Islands on September 22, 1944. There she was assigned to ComSoWesPac. The ship was to be dispensing ammunition and explosives to ships preparing for the Philippine offensive.

Task Group 29.6. She finally ended up Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island of the Admiralty Islands on September 22, 1944. There she was assigned to ComSoWesPac. The ship was to be dispensing ammunition and explosives to ships preparing for the Philippine offensive.

At 8:30am, on November 10, 1944, 17 of USS Mount Hood’s crew members, including Lieutenant Lester H Wallace left the ship to go ashore. At 8:55am, while walking on the beach the men saw a flash and heard two quick explosions. They immediately jumped back in their boat and headed for their ship, only to find that, like volcanoes tend to do, the USS Mount Hood had exploded. There was literally no ship to come back to, and other ships in the area were heavily damaged too. The USS Mount Hood had been anchored in 35 feet of water, and had exploded with an estimated 3,800 tons of ordnance material on board. Mushrooming smoke rose to 7,000 feet, completely obscuring the ship and the surrounding area for approximately 500 yards. It was easy to see where USS Mount Hood had been, because the explosion created a trench in the ocean floor 1,000 feet long, 200 feet wide, and 40 feet deep.The largest remaining piece of the hull was found in the trench and measured about 16 feet by 10 feet. No other remains were found except the fragments which struck the other ships in the area. No human remains were recovered of the 350 men aboard USS Mount Hood or the small boats loading alongside at the time of the explosion.

There were 271 men in surrounding ships that were injured, and 82 of nearby Mindanao’s crew were killed. In all, 22 small boats and landing craft were sunk, destroyed, or damaged beyond repair. The exact cause of USS Mount Hood’s explosion was never determined, but since the possibility of enemy action was remote, it was thought that rough handling of some of the explosives during the loading and unloading process was to blame for the disaster. With no survivors and so little of the ship left, I’m sure that the investigation was an impossible task. I do find it ironic that a ship named after a volcano, ended up exploding, and I find the loss of life to be a very sad thing indeed.

I don’t know of any family relationship that exists in my family or in Bob’s family, but I have always had an interest in Benjamin Franklin anyway. I have done a lot of hiking in my life, and sometimes, like it or not, bad weather comes in before we were done with our hike. I think anyone who has hiked much knows that one of your worst enemies on a hike…other than mountain lions, bears, or snakes…is lightning. Personally, when I start to hear thunder, I figure it’s time to head for shelter, but when you are four or five miles from your car, in the middle of a bunch of trees, heading for shelter isn’t always an easy task.

I don’t know of any family relationship that exists in my family or in Bob’s family, but I have always had an interest in Benjamin Franklin anyway. I have done a lot of hiking in my life, and sometimes, like it or not, bad weather comes in before we were done with our hike. I think anyone who has hiked much knows that one of your worst enemies on a hike…other than mountain lions, bears, or snakes…is lightning. Personally, when I start to hear thunder, I figure it’s time to head for shelter, but when you are four or five miles from your car, in the middle of a bunch of trees, heading for shelter isn’t always an easy task.

Ben Franklin, on the other hand saw lightning as a challenge to be explored. I think he had to have known the dangers of such an adventure, because he was a scientist after all. That didn’t really matter to him much, or if it did, he did not show it. Ben Franklin became interested in electricity in the mid-1740s. Not much was known about the subject, but he would spend the next decade conducting experiments using electricity. It was Ben who coined terms still in use today. You now them…battery, conductor, and electrician. He also invented the lightning rod, which is now used to protect buildings and ships. All of these things came from his many experiments. Ben Franklin was an amazing man, publisher, and writer, but it is really not in his writings that I find myself intrigued, but rather his electrical experiments. On this day, June 10, 1752, Ben flew his now infamous kite during a thunderstorm to collect a charge in a Leyden jar, when the kite was struck by lightning. He wanted to demonstrate the electrical nature of lightning.

Benjamin Franklin was born January 17, 1706. People might think that Benjamin Franklin was a highly educated man, but in reality, his formal education ended at age ten. Then he went to work for his brother, James as a printer, but after a dispute in 1723, he left Boston and moved to Philadelphia and found work as a printer. He moved to London for a short time and worked there as a printer, and then returned to Philadelphia. He became a successful businessman whose publishing ventures included the Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s Almanack, a collection of homespun proverbs advocating hard work and honesty in order to get  ahead. Eventually, Benjamin Franklin became an overachiever…or at least in the eyes of many people. I think he was just interested in a lot of things.

ahead. Eventually, Benjamin Franklin became an overachiever…or at least in the eyes of many people. I think he was just interested in a lot of things.

Of course, we all know about Benjamin Franklin’s career as a statesman, which spanned for decades, his years as a legislator, and his diplomatic years in England and France. He is the only politician to have signed all four documents fundamental to the creation of the US: the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Treaty of Alliance with France (1778), the Treaty of Paris (1783), which established peace with Great Britain, and the U.S. Constitution (1787). Yes, he was an all around amazing man, but I will always love the idea of his lightning experiments the best.

As the 73rd anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor dawns, I have to wonder why it is that the United States always feels that the other side must attack us first, and only then can we attack them. I know this is not always the case, but it seems like that is often the case. We try to be the peacemakers, and going to war is never something that we take lightly. Killing people is a horrible step to take. So, we always give warning after warning before we finally move, and even then it is usually too late to be the first to strike. I understand that the one who strikes first often looks like the bad guy, but it also seems like so often we are given much advance warning that a strike is eminent, and yet we wait…usually until after the attack happened and many people are dead, and the rest of us, while really angry, are too busy picking up the pieces to think about an immediate retaliatory strike.

As the 73rd anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor dawns, I have to wonder why it is that the United States always feels that the other side must attack us first, and only then can we attack them. I know this is not always the case, but it seems like that is often the case. We try to be the peacemakers, and going to war is never something that we take lightly. Killing people is a horrible step to take. So, we always give warning after warning before we finally move, and even then it is usually too late to be the first to strike. I understand that the one who strikes first often looks like the bad guy, but it also seems like so often we are given much advance warning that a strike is eminent, and yet we wait…usually until after the attack happened and many people are dead, and the rest of us, while really angry, are too busy picking up the pieces to think about an immediate retaliatory strike.

That was exactly where the United States found itself on December 7, 1941. We had warned Japan over and over, and with the Hull Note came the final warning. Even the fact that we knew that they would not comply, and we were in essence declaring war on Japan, we trusted them to move slowly…hoping for them to have a change of heart or something. They, on the other hand, acted almost immediately…or at least as immediate as they could back in 1941. They sent their strike force toward Pearl Harbor, while also sending a decoy strike force toward Thailand, in an effort to throw us off. Convinced that Japan was planning an attack on Thailand, President Roosevelt sent Emperor Hirohito a telegram, requesting that “for the sake of humanity,” the emperor intervene “to prevent further death and destruction in the world.” We were trying to be the peacemakers.

After sending the telegram, President Roosevelt was enjoying his stamp collection with his personal advisor, Harry Hopkins, and they were discussing the Japanese refusal to honor the Hull Note. Hopkins suggested that America should strike first, but President Roosevelt insisted that we could not do that. In reality, it was already to late for us to strike first. The Japanese were already on their way to attack Pearl Harbor, and a significant portion of the Pacific Fleet was there, anchored like sitting ducks, waiting for the attack. The ambush would take out 18 U.S. ships. Those destroyed, sunk, or capsized were the Arizona, Virginia, California, Nevada, and West Virginia. More than 180 planes were destroyed on the ground and another 150 were damaged, leaving only 43 planes operational. The American casualties totaled more than 3,400, with more than 2,400 killed…1,000 on the Arizona alone. The Japanese lost fewer than 100 men.

It seems to me that it is so often the side that strikes first…swiftly and with the element of surprise…that fares the best in the end. The side who was unaware, or didn’t heed the warning signs was slaughtered. We have one of the greatest military forces on the face of the earth here in America, so should we really ever be taken by surprise like that? I don’t think we should. I believe that if the strongman gets so sure of his might that he forgets the need to be watchful and wise, then when he least expects it, the strongman is caught unaware, and can be taken…even if his might should have prevented it. The United States has long been that strongman, and yet it seems that because of our hesitation to strike first, we are attacked over and over without warning. Then and only then, it seems, will we attack them in retaliation.

It is a dilemma I suppose, and maybe that was where President Roosevelt was coming from. We are the bad  guys with the world if we attack first, and we are the bad guys with our own nation if we do not attack first. And, to top it off our intelligence isn’t always as reliable as it needs to be, so sometimes, such as on December the 7th, 1941, we are caught off guard, and completely by surprise, when we trusted an enemy to be as honorable as we try to be, and they feel no such obligation to honor. I guess that while we don’t like it when we are attacked without provocation, we must nevertheless, do the honorable thing, and not attack just because we anticipate an attack on us. If we were to do that, we would be no different than the nations we have to go to war with because they have invaded some other nation. Still, it is so hard to always be the nation that does the right thing, when we really don’t trust our enemies…because we know better.

guys with the world if we attack first, and we are the bad guys with our own nation if we do not attack first. And, to top it off our intelligence isn’t always as reliable as it needs to be, so sometimes, such as on December the 7th, 1941, we are caught off guard, and completely by surprise, when we trusted an enemy to be as honorable as we try to be, and they feel no such obligation to honor. I guess that while we don’t like it when we are attacked without provocation, we must nevertheless, do the honorable thing, and not attack just because we anticipate an attack on us. If we were to do that, we would be no different than the nations we have to go to war with because they have invaded some other nation. Still, it is so hard to always be the nation that does the right thing, when we really don’t trust our enemies…because we know better.

One simply can’t go to Lake Superior and not go to Canal Park. There is nothing quite like watching a ship go through the canal and under the lift bridge. There is such an atmosphere of celebration, with kids playing and the birds flying everywhere. Crowds wait patiently for the arrival or departure of the next ship. Anticipation fills the air. It’s like being a kid at the movies for the first time. You almost can’t believe you are really there.

One simply can’t go to Lake Superior and not go to Canal Park. There is nothing quite like watching a ship go through the canal and under the lift bridge. There is such an atmosphere of celebration, with kids playing and the birds flying everywhere. Crowds wait patiently for the arrival or departure of the next ship. Anticipation fills the air. It’s like being a kid at the movies for the first time. You almost can’t believe you are really there.

As we waited for the next ship to go through the canal, I watched the people sitting around, trying to keep cool in the afternoon sun, while the little children tried in vain to catch the seagulls and pigeons that were flying around. The seagulls seemed to think it was a game of sorts, or maybe they were just hoping they would have some food for them. And lots of people did. It’s fun to feed the birds, even if the bread they were getting probably isn’t the best food for them. The seagulls would swoop over the people, and then almost hover in place, floating on the breeze, then they

would glide down to fly over the water in the canal, before going back to see if anyone had food again. It was such a pleasant flight to watch.

would glide down to fly over the water in the canal, before going back to see if anyone had food again. It was such a pleasant flight to watch.

Finally the moment came, and it was announced that a ship was coming in. The bridge started up and as many people as were able moved down to the side wall of the canal to get a closer look. The first ship to go under the bridge was a lake cruise ship. It was interesting, but it was not the spectacular sight I imagined. I just hoped that there would be a big oar boat coming through too. It looked as if I was about to be disappointed, then the announcer said that the Eeborg was about five minutes out. I didn’t see how he could possible make it into the canal within the allotted thirty minute window they had to keep the bridge up. Traffic was backed up from the island on the other side, waiting to come across. Nevertheless, the Eeborg moved much faster than I could have ever expected…especially for such a large ship.

Soon, there it was looming so tall in the canal. It wasn’t a luxury liner, and yet every person  there felt the same sense of awe at this amazing ship moving gracefully through the canal, under the bridge, and into the harbor to receive it’s load, before turning around and departing the next day, or later that night. It didn’t even matter if they had seen it a thousand times before, this scene still held them in captivating awe. Some of the ships that come here go all over the world…and their journey starts right there at Lake Superior. The horn sounded, and the Eeborg passed beneath the bridge and eventually out of our line of sight. I felt like I had seen a bit of a far reaching commerce, and it was very exciting.

there felt the same sense of awe at this amazing ship moving gracefully through the canal, under the bridge, and into the harbor to receive it’s load, before turning around and departing the next day, or later that night. It didn’t even matter if they had seen it a thousand times before, this scene still held them in captivating awe. Some of the ships that come here go all over the world…and their journey starts right there at Lake Superior. The horn sounded, and the Eeborg passed beneath the bridge and eventually out of our line of sight. I felt like I had seen a bit of a far reaching commerce, and it was very exciting.