chicago

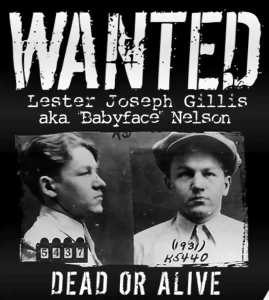

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

By the time he met his wife, Helen Wawrzyniak, Gillis (Baby Face Nelson) was working at a Standard Oil station in his neighborhood. Of course, that job wasn’t what it seemed either. The station doubled as the headquarters for a group of young tire thieves, known as “strippers” and Nelson fell into association with them. Through that association, Nelson acquainted himself with a number of local criminals. One of those criminals employed him to drive bootleg alcohol throughout the Chicago suburbs. Nelson quickly became a known member of the suburb-based Touhy Gang. All this happened by the time he was in his mid-teens. Very soon he became the Touhy Gang’s leader. In 1928, he married Helen Wawrzyniak, and they had two children, but that didn’t change his “bad boy ways” either. Within two years, Nelson and the gang were involved in organized crime, especially armed robbery. On January 6, 1930, the associates forced entry into the home of magazine executive Charles M Richter. After securing him up with adhesive tape and cutting the phone lines, they ransacked the house and made off with approximately $205,000 worth of jewelry, which would figure to approximately $3.3 million in 2021 dollars. Just two months later, they carried out a similar robbery at the bungalow of Lottie Brenner Von Buelow on Sheridan Road. This job netted approximately $50,000 worth of jewelry. After the crime, Chicago newspapers dubbed the gang, “The Tape Bandits.”

On April 21, 1930, Nelson and his gang robbed a bank for the first time. That take could hardly be considered  successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

Throughout the winter of 1931, most of the “Tape Bandits” were rounded up, including Nelson. The Chicago Tribune referred to their leader as “George ‘Baby Face’ Nelson” who received a sentence of one year to life in the state penitentiary at Joliet. Refusing to be held, Nelson escaped during a prison transfer in February 1932. Through his contacts within the Touhy Gang, Nelson fled west to Reno, where he was harbored by William Graham, a known crime boss and gambler. He began using the alias “Jimmy Johnson” at this point. Nelson…now Johnson went to Sausalito, California, where he worked for bootlegger Joe Parente.

Nelson decided that it was time for him to have a gang of his own after the Grand Haven bank robbery. Nelson used his connections at the Green Lantern Tavern in Saint Paul, to recruit Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll, and Eddie Green. With his new gang, and with the addition of two other local thieves, Nelson robbed the First National Bank of Brainerd, Minnesota on October 23, 1933. The take on that robbery was $32,000, or approximately $670,000 in 2021 dollars. It was reported that Nelson wildly sprayed sub-machine gun bullets at bystanders to facilitate his getaway. Then, he picked up his wife, Helen and four-year-old son Ronald, and left with his crew for San Antonio, Texas. In San Antonia, he and his gang bought several weapons from a crooked gunsmith Hyman Lehman, one of which was a .38 Super Colt pistol that had been modified, so it was fully automatic. That gun was used by Nelson to kill Special Agent W Carter Baum at Little Bohemia Lodge several months later.

On December 9, 1933, a local woman tipped off San Antonio police regarding “high-powered Northern gangsters” in the area. Tommy Carroll was cornered two days later by two detectives who opened fire, killing Detective H.C. Perrin and wounding Detective Al Hartman. At that point, the gang split up with all the Nelson gang, except Nelson, leaving San Antonio. As a way to distance himself from the gang, Nelson and his wife traveled west to the San Francisco Bay Area. The prior close call didn’t slow him down, however. In San Francisco, he recruited John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri for a new wave of bank robberies the following spring. The next winter found him in Reno, where he met the vacationing, Alvin Karpis. Karpis introduced him to Midwestern bank robber Eddie Bentz. Teaming up with Bentz, Nelson returned to the Midwest the next summer.  On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

Gillis Helped John Dillinger escape from prison in Crown Point, Indiana, and then became his partner. Nelson and the Touhy Gang were collectively “Public Enemy Number One” by the FBI. The alias, “Baby Face Nelson” came from Gillis being a short man with a youthful appearance. Still, in the professional realm, Gillis’ fellow criminals addressed him as “Jimmy.” On November 27, 1934, FBI agents fatally wounded and killed Baby Face Nelson in the Battle of Barrington, which was fought in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois.

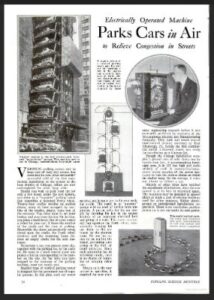

In 1932 Chicago was a city that was on the cutting edge of things, including car ownership. It wasn’t that everyone owned a car, but enough people did that there was beginning to be congestion problem where parking is concerned. It was especially bad for apartment buildings in the city. the people owned a car, but now they had to park so far away that they might as well not own a car. If they weren’t the first one home, they didn’t get to park close.

In 1932 Chicago was a city that was on the cutting edge of things, including car ownership. It wasn’t that everyone owned a car, but enough people did that there was beginning to be congestion problem where parking is concerned. It was especially bad for apartment buildings in the city. the people owned a car, but now they had to park so far away that they might as well not own a car. If they weren’t the first one home, they didn’t get to park close.

Enter the Car Parking Machine. Built by Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, the system took up the space of six cars at its base, but it held 48 cars. There are numerous compartments in the machine, and they are moving constantly in a vertical direction, like a car elevator. The system was run by an attendant, and when  they put a car in a slot, the machine moved it to the next open slot. When the car owner wanted his car back, the attendant rotated the structure until the right car was down, and then backed the car out for the owner, just to be safe.

they put a car in a slot, the machine moved it to the next open slot. When the car owner wanted his car back, the attendant rotated the structure until the right car was down, and then backed the car out for the owner, just to be safe.

The system was such a new phenomenon that they even came out with a short film about it called ‘Vertical Auto Park Solves Problem of Windy City.’ The film shows cars being driven in cages on conveyors that rise in a Ferris Wheel like manner. People look on as cars are carried by a 105-foot-high elevator that parks 48 cars in an area of 16 by 24 feet. It was filmed on location in Chicago, Illinois and aired on April 25, 1932. The Vertical Automatic Parking Lot was actually first tested in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania  before being set up as a commercial enterprise in the Chicago Loop during 1932.

before being set up as a commercial enterprise in the Chicago Loop during 1932.

While the system is really quite old, it isn’t necessarily out of date. For example, look at the latest way to buy a car…Carvana. While the purpose of the elevator system is different, the idea is still the same. You find your car online, and then you can go to the car vending machine to get your car. Just like the old system, your car takes a ride in the elevator to get to you. When you think about it, the system was a good one, and should probably be used in more places. Parking congestion is an ongoing problem, after all.

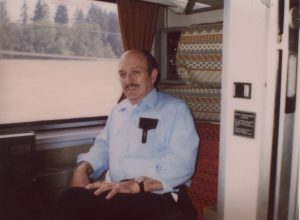

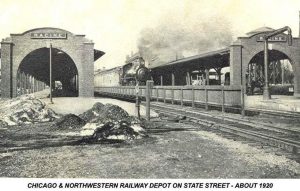

These days, people can buy a ticket to ride a train and have a private room with a bed and bathroom in it to make their trip more comfortable. Since I have taken a train trip from Seattle, Washington to Chicago, Illinois, I can tell you that paying the extra money for that private cabin is really a good idea. We traveled in in a seat among the other passengers, and while the seat was pretty comfortable, it was not comfortable to sleep in. My parents traveled on the Amtrack too, and they did get a private cabin, so their experience was probably much better than mine, although I loved the trip…just not the sleeping part of it. Of course, even with the comfort my parents had on

These days, people can buy a ticket to ride a train and have a private room with a bed and bathroom in it to make their trip more comfortable. Since I have taken a train trip from Seattle, Washington to Chicago, Illinois, I can tell you that paying the extra money for that private cabin is really a good idea. We traveled in in a seat among the other passengers, and while the seat was pretty comfortable, it was not comfortable to sleep in. My parents traveled on the Amtrack too, and they did get a private cabin, so their experience was probably much better than mine, although I loved the trip…just not the sleeping part of it. Of course, even with the comfort my parents had on  their trip, it was nothing compared to the Gilded Age, when the very rich had their own car on the train.

their trip, it was nothing compared to the Gilded Age, when the very rich had their own car on the train.

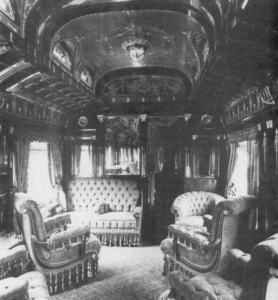

The Gilded Age was a time when the very rich went to great lengths to let all of the “less fortunate ones” know that they had wealth. The Gilded Age took place mostly from 1887 to 1900, with some earlier exceptions. One of the main objectives of life during the Gilded Age, if one could afford it, was to see and be seen in the most luxurious ways possible, and the railway was no different. Commercial air travel didn’t exist then, and cars were very slow. So, when the nation came into the age of the rails, the wealthy made sure that extreme luxury there was no exception. By the 1870s, private railroad cars…some extravagantly decorated…were the most fashionable way to travel. I suppose it would have been like the very

rich on ships, but they could stay a little closer to home, and still travel. The people would never travel in humble wooden coach seats, which I can understand, but most people had no other choice. Money bought comfort.

rich on ships, but they could stay a little closer to home, and still travel. The people would never travel in humble wooden coach seats, which I can understand, but most people had no other choice. Money bought comfort.

With great fanfare, the very rich boarded their own entire rail cars, where the walls were lined in velvet, the upholstery plush, and the decor much like that of a fancy parlor at home. The private cars had bedrooms, running water, and a private water closet. Now expense was spared to make sure that the wealthy car owner was never out of the lap of luxury. It seems like a cruel way to act, but I suppose it is simply the way it is.

Any kind of explosive can lead to danger. There are some industries that use explosives in their daily activities, and for the most part, all is well and people are safe. Nevertheless, there are those few situations, which always seem like they are so common, when they make the news. In reality, they are probably very rare, although I can’t say that for sure. It just seems to me that if these explosions were common, we would find a different way of doing things.

Any kind of explosive can lead to danger. There are some industries that use explosives in their daily activities, and for the most part, all is well and people are safe. Nevertheless, there are those few situations, which always seem like they are so common, when they make the news. In reality, they are probably very rare, although I can’t say that for sure. It just seems to me that if these explosions were common, we would find a different way of doing things.

On the night of February 24, 1922, in McCook, Illinois, a powder magazine exploded in a stone quarry. The quarry at McCook was on the outskirts of Chicago. The the explosion occurred, it shook the entire city. I know that explosions can be felt for miles and miles, and can even show up on seismometers. Still, Chicago is a big city. It seems odd to think that such a big city could feel the effects of an explosion, but that was just the beginning.  Windows were shattered in the south and the west portions of the city shortly before 9:30pm. People began calling the emergency numbers and calling newspapers to find out where the explosion had occurred and how many people had been killed. It seemed that no one knew at first, but soon it became obvious. An inquiry by The Associated Press to Indianapolis soon brought a bulletin from LaFayette, Indiana, that the explosion had occurred at McCook, Illinois.

Windows were shattered in the south and the west portions of the city shortly before 9:30pm. People began calling the emergency numbers and calling newspapers to find out where the explosion had occurred and how many people had been killed. It seemed that no one knew at first, but soon it became obvious. An inquiry by The Associated Press to Indianapolis soon brought a bulletin from LaFayette, Indiana, that the explosion had occurred at McCook, Illinois.

With that information they were able to find out within a few minutes that there had been an accident at the quarry which is situated in a rather secluded spot. It was found that no one had been killed, but early reports had no explanation as to how it occurred. The first definite report of the blast reached a Monon railroad signal tower at Dyer, Indiana. It was then relayed to the Monon dispatcher at LaFayette, before it came back to  Chicago over The Associated Press wire.

Chicago over The Associated Press wire.

The McCook quarry has had a long history problems that have been the direct result of quarry blasting. The quarries need to blast for loosen up the stone, but the effects can be devastating, even causing train derailments at times. The public has at times complained about the damages, but there didn’t seem to be much that could be done about it. Pictures of cracked walls and broken windows have been brought in for emphasis. I guess that until someone comes u with a better way to get the rock out of the quarry, the city will be stuck with the problem for the foreseeable future.

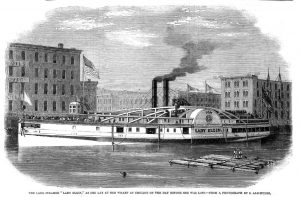

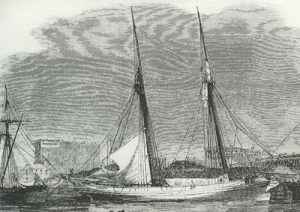

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

Suddenly, the lumber on the Augusta shifted, causing the two ships to collide. Instantly, the party atmosphere that had been on the Lady Elgin, turned to chaos and confusion. The Augusta received only minor damage in the collision, and kept right on sailing to Chicago. It wasn’t an unusual occurrence in those days. It’s possible that the Augusta assumed that if it wasn’t badly hurt, that larger ship probably wasn’t either. I can’t say for sure, but I know that this collision, in which the Augusta did not stop is not the first I have heard of such an incident in Maritime history. A large hole in the side of the Lady Elgin doomed the ship, which sank within thirty minutes. Only three lifeboats were able to be loaded and set into the water. The ships large upper hurricane deck fell straight into the water and served as a raft for some forty people.

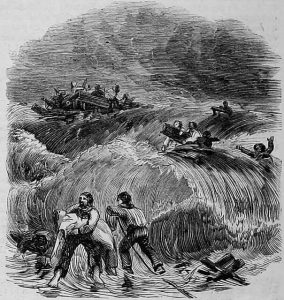

The ship had crashed two to three miles off the shore of Highland Park, but the waves were so strong that survivors, bodies, and debris were all swept down to the northern shore of Winnetka. In those days, the lakeshore in this area consisted of a narrow strip of beach rising up to clay cliffs almost 50 feet high. An angry line of breakers churned up from the storm were crashing ashore. Around 6:30am the first of the three lifeboats made it to shore in the vicinity of the Jared Gage house…which still stands at 1175 Whitebridge Hill Road. A desperate call for assistance went out to the town from the Gage house. The people of Winnetka rode  horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

The crowds on the bluffs and beaches watched as pieces of wreckage washed up near the site of the present Winnetka water tower. By 10:00am, the bluffs were littered with people who had been strong enough to withstand the fierce storm of the previous night. Lastly came the hurricane deck with Captain Wilson and eight survivors whom the storm had thus far spared. Then, before their eyes, this storm-battered deck was dashed to pieces on an offshore sandbar and all on board were lost.

The storm left a tremendous undertow, creating the tragic situation…the exhausted victims had drifted close enough to the Winnetka shore to see it, only to be held back by the breakers. As the horrified onlookers watch, they died in full view of the people on shore, who could do nothing but watch. Men were lowered from the bluff with rope tied around their waists in attempts to pull people in to safety. One Evanston seminary student, Edward Spencer, is credited with saving 18 lives. Spencer is said to have repeatedly rushed into the sea, being battered by debris in order to save more people. I do not know, but I suspect that he is some relation to me on my Spencer side, and I feel honored that he was such a heroic figure. Spencer is said to have wondered many times in the aftermath, “Did I do my best?” It is the mark of a hero, never to feel like they did enough. Another man, Joseph Conrad, was said to have pulled 28 to safety. Other unknown rescuers pulled in survivors up and  down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

The Gage house, the Artemas Carter house at 515 Sheridan Road, and other Winnetka residences served as temporary hospitals. The newly-built Winnetka train depot served as a morgue. Winnetka residents brought food and clothing for the survivors. It is estimated that 302 people lost their lives that day, the exact number is unknown, as the ships manifest went down with the ship. The 1860 census shows only 130 residents in the town of Winnetka. The tragedy captured the nation’s attention, but was quickly overshadowed by the 1860 elections and the Civil War. Such is the way of things. An tragic event is only well remembered, until another comes to take its place.

Every family struggles to find ways to do things together…not to mention the time to do so. Kids have their own activities, such as sports, dance, and other club and school activities. Parents work, kids have school, and then there are things that need to be done around the house. By the time dinner is cooked and eaten, and the table cleared, who feels like doing more activities. Plus, there is homework to be done. It seems like there isn’t time for anything more than a television show before bed.

Every family struggles to find ways to do things together…not to mention the time to do so. Kids have their own activities, such as sports, dance, and other club and school activities. Parents work, kids have school, and then there are things that need to be done around the house. By the time dinner is cooked and eaten, and the table cleared, who feels like doing more activities. Plus, there is homework to be done. It seems like there isn’t time for anything more than a television show before bed.

Most of us think this is just something that has come with modern day families, where they barely have time to eat dinner together…if that. In reality, it is a problem that has been around for a lot longer. Kids just naturally grow up and become more independent, and parents get busier too. Something had to be done, so in 1939, so Charles Steinlauf stepped up. He didn’t build his bicycle for a record, because there wasn’t such a thing then. The Guinness book of records didn’t begin until the early 1950’s. Nevertheless, he was some “inventor” to use the word lightly. His was an interesting bicycle, and apparently it held something for everyone…I guess. As odd as it was, the bicycle really  did work. The top rider, namely Charles steered the bicycle with an automobile steering wheel. His wife sat below operating a sewing machine. Their son was in back and their daughter sat on handle bars in front. When they stopped, the legs of the sewing machine kept the two story Goofybike, as it was called, from falling over. I don’t know any other way to safely stop it.

did work. The top rider, namely Charles steered the bicycle with an automobile steering wheel. His wife sat below operating a sewing machine. Their son was in back and their daughter sat on handle bars in front. When they stopped, the legs of the sewing machine kept the two story Goofybike, as it was called, from falling over. I don’t know any other way to safely stop it.

It might have been one of the strangest inventions in history, but, it did get his family out and about in Chicago, Illinois, and I’m certain it also brought them quite a bit of notoriety. I’m sure that there were lots of people who that of Steinlauf as that “weird inventor,” and to be honest, it looks like he just hooked a bunch of odds and ends together. It was, however, a little more technical than that, after all, just hooking a bunch of things together, does not a bicycle make. It has to be able to be ridden in order to really qualify as a bicycle, weird or not. And the Goofybike could be and was ridden by the whole Steinlauf family.

These days, the weather centers can predict storms weeks out. True, they aren’t always as accurate as we would like, but they can also predict corrections and update people with the changes. Of course, it is something we are used to in this day and age, but in 1941, weather centers didn’t exist. That was catastrophic for the people of North Dakota and Minnesota, when a fast-moving and quite severe blizzard hit on March 15th, killing 151 people. The storm came in so quickly that the people had no warning, and as a result far too many lost their lives.

These days, the weather centers can predict storms weeks out. True, they aren’t always as accurate as we would like, but they can also predict corrections and update people with the changes. Of course, it is something we are used to in this day and age, but in 1941, weather centers didn’t exist. That was catastrophic for the people of North Dakota and Minnesota, when a fast-moving and quite severe blizzard hit on March 15th, killing 151 people. The storm came in so quickly that the people had no warning, and as a result far too many lost their lives.

Because of that storm, weather forecasting and reporting systems made important advances that would have prevented the loss of life that occurred due to the sudden storm. The people of North Dakota and northern Minnesota had virtually no warning of the blizzard that was coming, until it swept in suddenly from the west on March 15. In some locations, temperatures dropped 20 degrees in less than 15 minutes. They were hit with 55 mile per hour sustained winds, and gusts reaching 85 miles per hour in Grand Forks and 75 miles per hour in Duluth. The winds  brought blinding snow and huge 7 foot high snow drifts across the states. Most of the victims of the blizzard were traveling in their cars when it hit. Highway 2, running from Duluth, Minnesota to North Dakota, was shut down, as were Highways 75 and 81. Attempts to rescue those stranded in their cars came too late. In one incident, six year old Wilbert Treichel died from exposure to the cold when his parents abandoned their car and attempted to carry him through the blizzard to safety.

brought blinding snow and huge 7 foot high snow drifts across the states. Most of the victims of the blizzard were traveling in their cars when it hit. Highway 2, running from Duluth, Minnesota to North Dakota, was shut down, as were Highways 75 and 81. Attempts to rescue those stranded in their cars came too late. In one incident, six year old Wilbert Treichel died from exposure to the cold when his parents abandoned their car and attempted to carry him through the blizzard to safety.

People attending a basketball game in Moorhead, Minnesota, were stranded at the arena overnight when it was wisely decided that travel was too dangerous for the 2,000 people. Theaters, hotels and stores across the region stayed open through the night to accommodate the many people had visited them, completely unaware that a major storm was approaching. Although the storm was also severe in Manitoba, Canada, only seven people there died because the population was much better prepared for the storm and for dangerous weather in general.

Prior to this time, meteorologists in Chicago were concerned mostly with local weather. It wasn’t that they did not care about the people in surrounding areas, but rather that it was not traditional reporting to report weather for the other areas. In the aftermath of this blizzard, weathermen in North Dakota and Minnesota, who had been under the control of the Chicago meteorology office, which simply paid less attention to events occurring to the north, were allowed autonomy in their reporting. Protected with new technological advances in the wake of the disaster, area residents hoped they would never again be so blind-sided by a winter storm.

Most plane crashes are caused by pilot error or mechanical failure, but sometimes, someone commits an act of terrorism, or as in the case of United Airlines Flight 629 someone commits an act of hatred aimed at one person. These acts are never rational, and this one certainly wasn’t, because Jack Gilbert Graham was not a rational man. I think many, if not most of us have thought at one point or another that our parents were somehow meaner to us than any other parent in the universe, but Jack Graham took that obsession to the next level. He decided that his mother was responsible for giving him a horrible childhood, and so he decided to take his revenge on her by placing a bomb in the luggage she was checking.

Most plane crashes are caused by pilot error or mechanical failure, but sometimes, someone commits an act of terrorism, or as in the case of United Airlines Flight 629 someone commits an act of hatred aimed at one person. These acts are never rational, and this one certainly wasn’t, because Jack Gilbert Graham was not a rational man. I think many, if not most of us have thought at one point or another that our parents were somehow meaner to us than any other parent in the universe, but Jack Graham took that obsession to the next level. He decided that his mother was responsible for giving him a horrible childhood, and so he decided to take his revenge on her by placing a bomb in the luggage she was checking.

His mother, Daisie Eldora King, who was a 53 year old Denver businesswoman was en route to Alaska to visit her daughter. Her flight United Airlines Flight 629, registration N37559, was a Douglas DC-6B aircraft also known as “Mainliner Denver.” The flight had originated at New York City’s La Guardia Airport and made a scheduled stop in Chicago before continuing to Denver’s Stapleton Airfield and landed at 6:11pm, 11 minutes late. At Denver the aircraft was refueled with 3,400 US gallons of fuel, and had a crew replacement. Captain Lee Hall, who was a World War II veteran, assumed command of the flight for the segments to Portland and  Seattle. The flight took off at 6:52pm and at 6:56pm made its last transmission stating it was passing the Denver omni. Seven minutes later, the Stapleton air traffic controllers saw two bright lights suddenly appear in the sky north-northwest of the airport. Both lights were observed for 30 to 45 seconds, and both fell to the ground at roughly the same speed. The controllers then saw a very bright flash originating at or near the ground, intense enough to illuminate the base of the clouds 10,000 feet above the source of the flash. Upon observing the mysterious lights, the controllers quickly determined there were no aircraft in distress and contacted all aircraft flying in the area; all flights were quickly accounted for except for United Flight 629. The date was November 1, 1955.

Seattle. The flight took off at 6:52pm and at 6:56pm made its last transmission stating it was passing the Denver omni. Seven minutes later, the Stapleton air traffic controllers saw two bright lights suddenly appear in the sky north-northwest of the airport. Both lights were observed for 30 to 45 seconds, and both fell to the ground at roughly the same speed. The controllers then saw a very bright flash originating at or near the ground, intense enough to illuminate the base of the clouds 10,000 feet above the source of the flash. Upon observing the mysterious lights, the controllers quickly determined there were no aircraft in distress and contacted all aircraft flying in the area; all flights were quickly accounted for except for United Flight 629. The date was November 1, 1955.

The plane was blown up over Longmont, Colorado at about 7:03pm local time, while en route from Denver, Colorado, to Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington. All 39 passengers and five crew members on board were killed in the explosion and crash. There was early speculation that something other than a mechanical problem or pilot error was responsible, given the magnitude of the in-air explosion. Investigators determined that Jack Gilbert Graham was responsible for bombing the airplane to kill his mother as revenge for his childhood and to obtain a large life insurance payout. Within 15 months of the explosion, Graham, who already had an extensive criminal record, was tried, convicted, and executed for the crime.

It was a horrible thing. One sick man committed murder in the skies, by killing his mother with a bomb, and in the process killed 41 other people too. I don’t know if he though the could really get away with it, but investigations are pretty sophisticated…even back then. It amazes me that they can take all those plane parts and examine them…somehow finding the source of the explosion, and tracing it back to the source. Then, by finding out who the luggage belonged to, they figured the whole thing out. Criminals really aren’t so smart, even though they think they have it all figured out. It is just sad that 42 people lost their lives, because some spoiled brat of a child thought his mom was too harsh when he was a kid…with no evidence to prove his point at all.

It was a horrible thing. One sick man committed murder in the skies, by killing his mother with a bomb, and in the process killed 41 other people too. I don’t know if he though the could really get away with it, but investigations are pretty sophisticated…even back then. It amazes me that they can take all those plane parts and examine them…somehow finding the source of the explosion, and tracing it back to the source. Then, by finding out who the luggage belonged to, they figured the whole thing out. Criminals really aren’t so smart, even though they think they have it all figured out. It is just sad that 42 people lost their lives, because some spoiled brat of a child thought his mom was too harsh when he was a kid…with no evidence to prove his point at all.

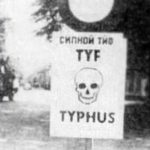

Heroes come in many forms, but few could be said to have been as sneaky as Eugene Lazowski, who was born Eugeniusz Slawomir Lazowski, in 1913 in Poland. His bravery was combined with genius, and in the end, he saved 8,000 Polish Jews at the height of the Holocaust. Lazowski saw the horrible way the Jews were treated, and he saw a way to help. Eugene Lazowski had just finished medical school when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. Typhus was spreading across the country. The disease was killing an average of 750 people a day. In an attempt to contain the disease, the Nazis increased their isolation and execution of Jews. Eugene joined the Polish Red Cross, but he was forbidden by the Nazis from treating Jewish patients. Nevertheless, under the cover of darkness, he sneaked into the Jewish ghetto and took care of the people there. Lazowski’s plan took an incredible amount of intellect, not to mention bravery. His life was on the line too. Lazowski created the illusion of an epidemic of a deadly disease, playing on the deep fears of the Nazis.

Heroes come in many forms, but few could be said to have been as sneaky as Eugene Lazowski, who was born Eugeniusz Slawomir Lazowski, in 1913 in Poland. His bravery was combined with genius, and in the end, he saved 8,000 Polish Jews at the height of the Holocaust. Lazowski saw the horrible way the Jews were treated, and he saw a way to help. Eugene Lazowski had just finished medical school when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. Typhus was spreading across the country. The disease was killing an average of 750 people a day. In an attempt to contain the disease, the Nazis increased their isolation and execution of Jews. Eugene joined the Polish Red Cross, but he was forbidden by the Nazis from treating Jewish patients. Nevertheless, under the cover of darkness, he sneaked into the Jewish ghetto and took care of the people there. Lazowski’s plan took an incredible amount of intellect, not to mention bravery. His life was on the line too. Lazowski created the illusion of an epidemic of a deadly disease, playing on the deep fears of the Nazis.

The plan came about in an unusual way. One day, a Polish soldier on leave begged Eugene and his colleague, Dr Stanislaw Matulewicz, to help him avoid returning to the warfront. I think there were many people who fought on the Nazi side of that era, who would give anything not to take part in what the Nazis were all about. Matulewicz had discovered that by injecting a healthy person with a vaccine of dead bacteria, that person would test positive for epidemic typhus without experiencing the symptoms. In an attempt to help the young solider fake a life-threatening illness, the doctors who had discovered that a dead strain of the Proteus OX19 bacteria in typhus would still lead to a positive test for the disease. Eugene realized that this could be used as a defense against the Nazis.

The plan came about in an unusual way. One day, a Polish soldier on leave begged Eugene and his colleague, Dr Stanislaw Matulewicz, to help him avoid returning to the warfront. I think there were many people who fought on the Nazi side of that era, who would give anything not to take part in what the Nazis were all about. Matulewicz had discovered that by injecting a healthy person with a vaccine of dead bacteria, that person would test positive for epidemic typhus without experiencing the symptoms. In an attempt to help the young solider fake a life-threatening illness, the doctors who had discovered that a dead strain of the Proteus OX19 bacteria in typhus would still lead to a positive test for the disease. Eugene realized that this could be used as a defense against the Nazis.

The two doctors hatched a secret plan to save about a dozen villages in the vicinity of Rozwadów and Zbydniów not only from forced labor exploitation, but also Nazi extermination. Lazowski began distributing the phony vaccine widely. Within two months, so many new (fake) cases were confirmed that Eugene successful  convinced his Nazi supervisors a typhus epidemic had broken out. The Nazis immediately quarantined areas with suspected typhus cases, including those with Jewish inhabitants. In 12 other villages, Eugene created safe havens for Jews through these quarantines. His work would eventually save 8,000 Jewish lives.

convinced his Nazi supervisors a typhus epidemic had broken out. The Nazis immediately quarantined areas with suspected typhus cases, including those with Jewish inhabitants. In 12 other villages, Eugene created safe havens for Jews through these quarantines. His work would eventually save 8,000 Jewish lives.

When the war ended, Eugene continued to practice medicine in Poland until he was forced to flee with his family to the United States. They settled in Chicago, where Eugene earned a medical degree from the University of Illinois. Decades later, he finally returned to Poland, where he received a hero’s welcome for saving those in desperate need of salvation through his unyielding love for humanity.

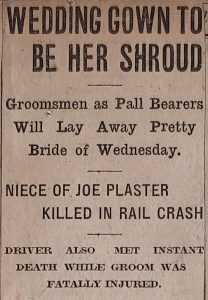

The headline read “Wedding Gown To Be Her Shroud.” The newspaper article was about a horrible tragedy, that took place just four days after the wedding of my husband, Bob’s 6th cousin 3 times removed, Ruth Schulenberg to Wilberd Youngman. The wedding took place on November 26, 1913, and was a large social affair for the smaller town of Tolono, Illinois, population of about 700, at the time. Ruth Schulenberg, was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Henry Schulenberg, and was a graduate of Saint Mary’s of the Wood where she was a member of a prominent sorority. Wilberd Youngman employed as a draughsman by the Burr Company of Champaign, Illinois. The wedding took place at Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church in Tolono.

The headline read “Wedding Gown To Be Her Shroud.” The newspaper article was about a horrible tragedy, that took place just four days after the wedding of my husband, Bob’s 6th cousin 3 times removed, Ruth Schulenberg to Wilberd Youngman. The wedding took place on November 26, 1913, and was a large social affair for the smaller town of Tolono, Illinois, population of about 700, at the time. Ruth Schulenberg, was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Henry Schulenberg, and was a graduate of Saint Mary’s of the Wood where she was a member of a prominent sorority. Wilberd Youngman employed as a draughsman by the Burr Company of Champaign, Illinois. The wedding took place at Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church in Tolono.

After their wedding, the young couple was on their honeymoon, in Kokomo, Indiana, where they had attended church at the Kokomo Catholic Church. Following the church service, they were on their way to a big wedding dinner in their honor at the country residence of a neighbor of Youngman’s cousin, Edward Grishaw, who was

transporting the couple in a closed carriage. As the carriage began its crossing of the tracks of the Lake Erie and Western Railway, Grishaw failed for look for trains, and pulled out in front of the Lake Erie train going full speed. The train ripped through the car, and by the time the train could stop and the crew reached the car’s occupants, Ruth Schulenberg and Edward Grishaw were dead. Wilberd Youngman was critically injured, and not expected to live.

transporting the couple in a closed carriage. As the carriage began its crossing of the tracks of the Lake Erie and Western Railway, Grishaw failed for look for trains, and pulled out in front of the Lake Erie train going full speed. The train ripped through the car, and by the time the train could stop and the crew reached the car’s occupants, Ruth Schulenberg and Edward Grishaw were dead. Wilberd Youngman was critically injured, and not expected to live.

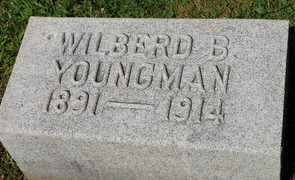

Amazingly, Wilberd Youngman did live…for eleven months. Youngman was taken to a hospital in Chicago, but his prognosis was grim. People just don’t come back from being hit by a train that ripped their car apart, and yet he was still alive, and actually recovering from his injuries…the visible injuries anyway. Youngman had lost so much that November day, and he was struggling to move forward. Ruth Schulenberg had been his soulmate, and his very best friend. She was the love of his life, and he knew there could never be another woman for him. Wilberd Youngman was not a man who would commit suicide, but he also could not recover from this deepest injury…the one that broke his heart. Slowly, over the eleven months that followed the saddest day of  his life, Wilberd Youngman dwindled away. it wasn’t a refusal of food and water, but rather a refusal to go on without his precious Ruth. Finally, on October 24, 1914, just short of 11 months after that awful day…November 30, 1913, Wilberd Youngman could no longer go on living, and so, with his parents by his side, he simply passed away. The final cause of death was listed as a broken heart. That, to me was the saddest cause of death I had ever heard. Because of the loss of his wife, Wilberd simply had no desire to live either. He tried to recover…physically, but his heart was no longer in it, and he finally just gave up and quit trying. The Honeymoon Tragedy had finally claimed it’s last victim.

his life, Wilberd Youngman dwindled away. it wasn’t a refusal of food and water, but rather a refusal to go on without his precious Ruth. Finally, on October 24, 1914, just short of 11 months after that awful day…November 30, 1913, Wilberd Youngman could no longer go on living, and so, with his parents by his side, he simply passed away. The final cause of death was listed as a broken heart. That, to me was the saddest cause of death I had ever heard. Because of the loss of his wife, Wilberd simply had no desire to live either. He tried to recover…physically, but his heart was no longer in it, and he finally just gave up and quit trying. The Honeymoon Tragedy had finally claimed it’s last victim.