british

I am sometimes amazed at the ability of humans to be heinously cruel to other human beings. From murders, to slave owners, to prisons or prisoner of war camps, man has the ability to act out evil in its purest form. Still, one would not have expected such evil in the American Revolutionary War era. Well, one would be wrong. We all know that war is a horrific event, but worse than losing life and limb in battle, seems to be the fate faced by those who are captured by the enemy forces, only to be tortured and even killed.

I am sometimes amazed at the ability of humans to be heinously cruel to other human beings. From murders, to slave owners, to prisons or prisoner of war camps, man has the ability to act out evil in its purest form. Still, one would not have expected such evil in the American Revolutionary War era. Well, one would be wrong. We all know that war is a horrific event, but worse than losing life and limb in battle, seems to be the fate faced by those who are captured by the enemy forces, only to be tortured and even killed.

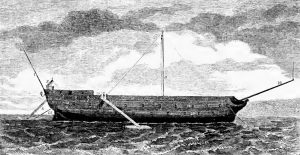

During the Revolutionary War, being captured by the British often meant being sent to a prison ship, the worse of which was the HMS Jersey. Over the years of the war, approximately 11,000 prisoners of war perished on the HMS Jersey. The number of American field casualties during that war was approximately 4,500. That is a stunning difference. The HMS Jersey often held thousands of prisoners at one time, in quarters that were so close, that it could be likened to being packed in like sardines in a tin. There was no light, no medical care, barely any oxygen, and very little in the way of food and clean water. The guards on the prison ships were not concerned with keeping their prisoners alive, and HMS Jersey was the worst of them all.

The little food the prisoners were given was moldy, putrefied, and worm infested. The prisoners had to choose daily to eat the horrible food, or starve. One prisoner Ebenezer Fox, who survived said, “The bread was mostly mouldy, and filled with worms. It required considerable rapping upon the deck, before these worms could be dislodged from their lurking places in a biscuit. As for the pork, we were cheated out of it more than half the time, and when it was obtained one would have judged from its motley hues, exhibiting the consistence and appearance of variegated soap, that it was the flesh of the porpoise or sea hog, and had been an inhabitant of the ocean, rather than a sty. The provisions were generally damaged, and from the imperfect manner in which they were cooked were about as indigestible as grape shot.” That pretty much says it all, I would say. The British soldiers were seemingly unaffected by the image of prisoners banging their biscuits against the deck to remove worms, because this treatment continued throughout the conflict.

Because the prisoners were kept at sea, the smell of a piece of dirt from the shoes of a soldier back from shore leave became one of the prisoners’ greatest delights. I guess that one can always find some good, even in the worst situations, if one looks for it. Captain Dring, a survivor who wrote prolifically about his experiences on the Jersey, recalled one particularly strange consolation. When someone died on the ship, their remains were usually thrown overboard, but occasionally they were allowed to be taken ashore and laid to rest. Dring was part of a group that was tasked with digging graves on land. The men chosen for this duty were ecstatic to be on land again. Dring even took off his boots simply to feel the earth underneath his feet. However, when the crew came across a piece of broken-up turf, they did something extraordinary: “We went by a small patch of turf, some pieces of which we tore up from the earth, and obtained permission to carry them on board for our comrades to smell them. Circumstances like these may appear trifling to the careless reader; but let him be assured that they were far from being trifles to men situated as we had been. Sadly did we approach and reenter our foul and disgusting place of confinement. The pieces of turf which we carried on board were sought for by our fellow prisoners, with the greatest avidity, every fragment being passed by them from hand to hand, and its smell inhaled as if it had been a fragrant rose.”

The known fate of the men on board the prison ships, and especially HMS Jersey was a slow and painful death. Most knew better than to expect to survive their ordeal. They had seen too many of their comrades die right before their eyes, to have much hope that they could make it out. To make mattes worse, the majority of the prisoners aboard the Jersey were young, inexperienced farmhands, not hardened soldiers with survival experience. Only a few of Washington’s army were soldiers with any  experience. The rest were provincial people, and many had never traveled beyond the limits of the small county where they lived. Imagine the horror of war, and then the conditions on HMS Jersey to the young, innocent men. The constant punishment, meager rations, lack of light, and lack of privacy could be tolerated, but the inactivity and helplessness most likely added depression and despair to their suffering. Times were different then, and there were things that were not available, but many of the things the prisoners suffered could have been avoided, especially the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, but apparently they just didn’t care.

experience. The rest were provincial people, and many had never traveled beyond the limits of the small county where they lived. Imagine the horror of war, and then the conditions on HMS Jersey to the young, innocent men. The constant punishment, meager rations, lack of light, and lack of privacy could be tolerated, but the inactivity and helplessness most likely added depression and despair to their suffering. Times were different then, and there were things that were not available, but many of the things the prisoners suffered could have been avoided, especially the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, but apparently they just didn’t care.

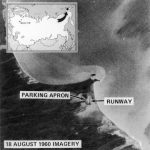

World War II brought with it necessary changes to war ships. Suddenly, the world had planes that could fly greater distances, and even had the ability to land on a ship, provided the ship was big enough to have a relatively short runway. I say relatively short, because the runways on ships seemed like they would be too short to safely land a plane, but they did. One such ship was the HMS Ark Royal.

World War II brought with it necessary changes to war ships. Suddenly, the world had planes that could fly greater distances, and even had the ability to land on a ship, provided the ship was big enough to have a relatively short runway. I say relatively short, because the runways on ships seemed like they would be too short to safely land a plane, but they did. One such ship was the HMS Ark Royal.

The Ark Royal was an English ship designed in 1934 to fit the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty. The ship was built by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead, England, and was completed in November 1938. The design of this ship differed from previous aircraft carriers, in that Ark Royal was the first ship on which the hangars and flight deck were an integral part of the hull, instead of an add-on or part of the superstructure. This ship was designed to carry a large number of aircraft. There were two hangar deck levels. HMS Ark Royal served during a period of time during which we first saw the extensive use of naval air power. The Ark Royal played an integral part in developing and refining several carrier tactics.

HNS Ark Royal served in some of the most active naval theatres of the World War II. The ship was involved in the first aerial and U-boat kills of the war, operations off Norway, the search for the German battleship Bismarck, and the Malta Convoys. After Ark Royal survived several near misses, she became known as a “lucky ship” and the reputation stuck…at least until November 13, 1941, when the German submarine U-81 torpedoed her and she sank the following day. Nevertheless, only one of her 1,488 crew members was killed. Her sinking was the subject of several inquiries. While only one man was killed, investigators still couldn’t figure out how the carrier was lost…in spite of efforts to tow her to the naval base at Gibraltar. In the end, they found that several design flaws contributed to the loss. These flaws were rectified in subsequent British carriers. There was, of course, no time to look for the ship then. The war was still going on.

The wreck was discovered in December 2002 by an American underwater survey company using sonar mounted on an autonomous underwater vehicle. The company was under contract from the BBC for the filming of a documentary about the HMS Ark Royal. The ship was at a depth of about 3,300 feet and approximately 30 nautical miles from Gibraltar. So close, and yet so far away.

Most people have heard of, and seen, the James Bond movies. Of course, Bond is a fictional British agent, known as 007, and his character has been played by a number of actors over the years, but in reality, he is fictional. Renato Levi, who was also known as CHEESE, MR. ROSE, LAMBERT, EMILE, or ROBERTO, was a Jewish-Italian adventurer and double-agent for the British in World War II. Levi was instrumental in setting up a wireless transmitter in Cairo. The transmitter fed false information to the Axis powers over the course of the war. It was a great tool for the Allies. Unfortunately, Levi was captured and imprisoned shortly after he accomplished his mission. Levi’s “CHEESE” network helped to outflank Rommel at the battle of El Alamein in Egypt, as well as placing other, strategic misinformation that aided the Allies, including at Normandy.

Most people have heard of, and seen, the James Bond movies. Of course, Bond is a fictional British agent, known as 007, and his character has been played by a number of actors over the years, but in reality, he is fictional. Renato Levi, who was also known as CHEESE, MR. ROSE, LAMBERT, EMILE, or ROBERTO, was a Jewish-Italian adventurer and double-agent for the British in World War II. Levi was instrumental in setting up a wireless transmitter in Cairo. The transmitter fed false information to the Axis powers over the course of the war. It was a great tool for the Allies. Unfortunately, Levi was captured and imprisoned shortly after he accomplished his mission. Levi’s “CHEESE” network helped to outflank Rommel at the battle of El Alamein in Egypt, as well as placing other, strategic misinformation that aided the Allies, including at Normandy.

Levi almost always flew under the radar, especially in the British National Archives. Even in recent books about spies and counter-intelligence, the accomplishments of Renato Levi still receive barely a mention and the specifics about his part in all this is often confused. In all reality, Levi’s files have only recently been released, and even then Levi’s, aliases “Cheese,” “Lambert,” or “Mr. Rose” seem to be identified openly only once in his classified dossier. Indeed, in his national documents, there is evidence of redaction everywhere, including Levi’s primary codename “CHEESE” has been carefully handwritten in tiny, blocky letters over white-out, in order to re-establish a place in history.

The CHEESE network, out of Cairo, took a significant hit to its credibility when Levi was arrested and convicted in late 1941 or early 1942. The British came up with an imaginary agent. “Paul Nicossof” was able to regain and retain the trust of the Germans, which is one of the most interesting features of this story. Thanks to the expert manipulations of the British Intelligence operatives controlling the wireless, the CHEESE network was considered credible again by June of 1942…just in time for “A” Force to start planting counter-intelligence prior to the commencement of Operation Bertram at El Alamein in Egypt during October of 1942.

Most interesting to note are the ways that the intelligence operatives used payment schedules…or, rather, the German’s lack of payment to “Paul Nicossof”…to establish credibility about the fictitious informant’s information. “Nicossof” was portrayed as moody and inconsistent, because efforts to pay him were always unsuccessful. His “handlers” credited Germany’s inability to pay “Nicossof” as the way they were able to extend his character beyond the “impasse” that would normally constitute a non-military informant. “Nicossof” could portray himself as the “man who brought Rommel to Egypt,” which would get him paid for his troubles at last, as well as the glory and medals that went with it…all to a fictitious agent!!

Most interesting to note are the ways that the intelligence operatives used payment schedules…or, rather, the German’s lack of payment to “Paul Nicossof”…to establish credibility about the fictitious informant’s information. “Nicossof” was portrayed as moody and inconsistent, because efforts to pay him were always unsuccessful. His “handlers” credited Germany’s inability to pay “Nicossof” as the way they were able to extend his character beyond the “impasse” that would normally constitute a non-military informant. “Nicossof” could portray himself as the “man who brought Rommel to Egypt,” which would get him paid for his troubles at last, as well as the glory and medals that went with it…all to a fictitious agent!!

Perhaps because of the British Intelligence’s efforts to make “Nicossof” convincing and because Levi was so good under duress in prison, the Germans never really lost faith in the CHEESE operative network. They were starved for information, and CHEESE held the only promise for any intelligence about the Middle East. The Germans blamed the Italians for the confinement of their only key agent in the Middle East, Renato Levi. For whatever the reason, the Germans trusted Levi, but he never broke or compromised his duty to the Allied forces.

After looking at these newly declassified documents some people have tried to press Levi into the service of a “Hero Spy” figure, but in reality, Levi was a far more complicated figure and these whitewashed narratives don’t really tell the whole story of Levi’s complexity, nor the complexity of his work. Levi’s story also reveals much about the inner workings of the German Abwehr and the nature of the Italian Intelligence operations. Levi’s British handlers speculated that it was unlikely that the German and Italian Intelligence bureaus had a great deal of communication between them. The Germans were really overly satisfied with Levi’s original purpose of  establishing a wireless transmitter network, to their detriment in the end.

establishing a wireless transmitter network, to their detriment in the end.

It seems that Levi’s ultimate fate is unknown. It is true that the CHEESE network was in full swing throughout the war, and many have credited “CHEESE” with hoodwinking the Germans in a big way on many occasions. Perhaps Levi was again affiliated with CHEESE after his release, or maybe not. Regardless, Renato Levi, who had always loved travel, intrigue, and a really good lie, did a remarkable service to the Allied forces by instituting one of the best and most productive counter-intelligence operations of World War II, and he kept it all safe.

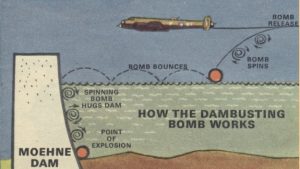

We have all tried our hand at skipping stones across the water, but who would have thought that such an idea could be applied to a bomb, or that it would ultimately become extremely successful in accomplishing its given task…destroying German dams and hydroelectric plants along the Ruhr valley.

We have all tried our hand at skipping stones across the water, but who would have thought that such an idea could be applied to a bomb, or that it would ultimately become extremely successful in accomplishing its given task…destroying German dams and hydroelectric plants along the Ruhr valley.

During World War II, the Allies we’re desperate to cut off energy to the Nazi war machine, so the Allied engineers were given the task of finding a way to breach the defenses surrounding the dams and hydroelectric plants. In the end, it was British engineer, Barnes Wallis who came through with what he called “bouncing bombs.” To watch it in action, one is reminded of skipping stones like most of us have done in the past. In similar fashion, the bomb skips along the water bouncing over the torpedo nets to hit its target.

When World War II began, Germany had the undisputed upper hand when it came to water-based warfare with

their deadly U-boats and defensive “torpedo nets” placed strategically in front of their energy-creating dams. This made it next to impossible to hit the dams with the traditional torpedo. The British Royal Air Force was determined to take out these German battlements, as they slowly wore the Axis of Evil down.

their deadly U-boats and defensive “torpedo nets” placed strategically in front of their energy-creating dams. This made it next to impossible to hit the dams with the traditional torpedo. The British Royal Air Force was determined to take out these German battlements, as they slowly wore the Axis of Evil down.

The problem was, how to somehow get past the torpedo nets, to destroy the dams and their hydroelectric plants. Wallis had to figure out how to bypass the torpedo nets, in order to make direct contact with the wall of the dams. It seemed like an insurmountable task. After dwelling on the problem for a while, Wallis seized on

the potential of the Magnus effect, which would bounce a bomb across the water like a skipping stone.

the potential of the Magnus effect, which would bounce a bomb across the water like a skipping stone.

The theory was to create backspin, which would counter the gravity and send the bomb skimming over the water. Once it bounced over the torpedo net, it hit the designated target. The plan seemed plausible, and the Royal Air Force commenced Operation Chastise on May 16, 1943. The results were spectacular!! As it turned out, Barnes Wallis really knew his stuff.

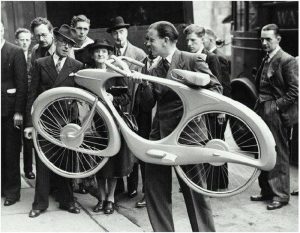

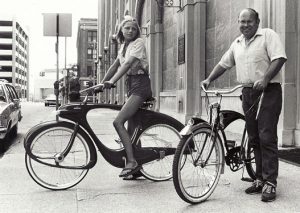

Today it would be worth about $4750. Would you pay that much for a bicycle? I don’t think I would, but then I don’t suppose I would be buying a bicycle called the Spacelander. Still, if I was, $4750 would be the asking price, or something close to that number. The Spacelander was created by Benjamin Bowden, who was born June 3, 1906. He was a British industrial designer, whose specialty was automobiles and bicycles. He received violin training at Guildhall, and completed a course in engineering at Regent. Bowden designed the coachwork of Healey’s Elliott, an influential British sports car.

Today it would be worth about $4750. Would you pay that much for a bicycle? I don’t think I would, but then I don’t suppose I would be buying a bicycle called the Spacelander. Still, if I was, $4750 would be the asking price, or something close to that number. The Spacelander was created by Benjamin Bowden, who was born June 3, 1906. He was a British industrial designer, whose specialty was automobiles and bicycles. He received violin training at Guildhall, and completed a course in engineering at Regent. Bowden designed the coachwork of Healey’s Elliott, an influential British sports car.

In 1925 Bowden began working as an automobile designer for the Rootes Group. By the late 1930s, Bowden was the chief body engineer for the Humber car factory in Coventry. During World War II, his design of an armored car was used by Winston Churchill and George VI for their protection. In 1945, he left the Rootes Group, and with partner John Allen, formed his own design company in Leamington Spa. The studio was one of the first such design firms in Britain. Bowden designed the body of Healey’s Elliott in 1947. It was the first British car to break the 100 mile per hour barrier. Working with Achille Sampietro who created the chassis, Bowden drew the initial design for the auto directly onto the walls of his house. Unusual…yes, but it worked for him, I guess. Shortly before his departure to the United States Bowden penned a sketch design for a two-seater sports racing prototype, the Zethrin Rennsport, being developed by Val Zethrin. This used the same wheelbase as the short-chassis Squire Sports, and was dressed in a contemporary, streamlined body. This design theme was carried through to his future work on the early Chevrolet Corvette and Ford Thunderbird.

He went on to design the Spacelander in 1946. It was a space-age looking bicycle, that was ahead of its time, since space travel wouldn’t occur for two decades. It’s not that the Spacelander would ever be used in space, but rather the design that seemed space-like. Bowden called the bicycle the Classic. In the early or mid 1950s, Bowden moved to Michigan, in the United States. While in Muskegon, Michigan in 1959, he met with Joe Kaskie, of the George Morrell Corporation, a custom molding company. Kaskie suggested molding the bicycle in fiberglass instead of aluminum, but the fiberglass frame was relatively fragile, and its unusual nature made it difficult to market to established bicycle distributors. Although he retained the futuristic appearance of the Classic, Bowden abandoned the hub dynamo, and replaced the drive-train with a more common sprocket-chain assembly. The new name, Spacelander, was chosen to capitalize on interest in the Space Race. Financial

troubles from the distributor forced Bowden to rush development of the Spacelander, which was released in 1960 in five colors: Charcoal Black, Cliffs of Dover White, Meadow Green, Outer Space Blue, and Stop Sign Red. The bicycle was priced at $89.50, which made it one of the more expensive bicycles on the market. Only 522 Spacelander bicycles were shipped before production was stopped, although more complete sets of parts were manufactured. In more recent years, the Spacelander has become a collector’s item…hence the price tag.

troubles from the distributor forced Bowden to rush development of the Spacelander, which was released in 1960 in five colors: Charcoal Black, Cliffs of Dover White, Meadow Green, Outer Space Blue, and Stop Sign Red. The bicycle was priced at $89.50, which made it one of the more expensive bicycles on the market. Only 522 Spacelander bicycles were shipped before production was stopped, although more complete sets of parts were manufactured. In more recent years, the Spacelander has become a collector’s item…hence the price tag.

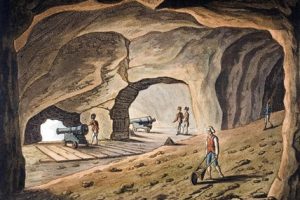

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

After reading about the rescue of Allied personnel from occupied France by smuggling them through Spain and then to the Rock of Gibraltar, I wanted to know more about this place. The story talked about the tunnels that basically created an underground city in the Rock of Gibraltar. The Rock was basically a huge underground fortress capable of accommodating 16,000 men along with all the supplies, ammunition, and equipment needed to withstand a prolonged siege. The entire 16,000 strong garrison could be housed there along with enough food to last them for 16 months. Within the tunnels there were also an underground telephone exchange, a power generating station, a water distillation plant, a hospital, a bakery, ammunition magazines and a vehicle maintenance workshop. Such a place in World War II would be almost impossible to penetrate with the weapons available in that day and age.

The tunnels of Gibraltar were constructed over the course of nearly 200 years, principally by the British Army. Within a land area of only 2.6 square miles, Gibraltar has around 34 miles of tunnels, nearly twice the length of its entire road network. The first tunnels were excavated in the late 18th century. They served as communication passages between artillery positions and housed guns within embrasures cut into the North Face of the Rock, to protect the interior city. More tunnels were constructed in the 19th century to allow easier access to remote areas of Gibraltar and accommodate stores and reservoirs to deliver the water supply of

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

Gibraltar. At the start of World War II, the civilian population around the Rock of Gibraltar was evacuated and the garrison inside the facility was greatly increased in size. A number of new tunnels were excavated to create accommodation for the expanded garrison and to store huge quantities of food, equipment, and ammunition. The work was carried out by four specialized tunneling companies from the Royal Engineers and the Canadian Army. They created a new Main Base Area in the southeastern part of Gibraltar on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. It was chosen because it was shielded from the potentially hostile Spanish mainland. New connecting tunnels were created to link this with the established military bases on the west side. A pair of tunnels, called the Great North Road and the Fosse Way, were excavated running nearly the full length of the Rock to interconnect the bulk of the wartime tunnels.

It was to this place that the French Resistance smuggled downed Allied airmen and other escapees from the Nazi regime inside France. Men like Staff Sergeant Arthur Meyerowitz and RAF Bomber Lieutenant R.F.W. Cleaver…two of the men who were smuggled out of occupied France by the French Resistance network known as Réseau Morhange which was created in 1943 by Marcel Taillandier in Toulouse. Taillandier was killed shortly after these two men were smuggled out. He had given his life to protect the airmen he smuggled out as well as to provide intelligence to England. For the airmen who made it to the Rock of Gibraltar, freedom awaited. While

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

the road had been long and hard, the time spent at the Rock of Gibraltar meant safety, medical care, food, and warmth. It meant being able to let their family know that they were alive. It meant being able to go back to life, and maybe for some, to be able to live to fight another day. As the men were told upon arrival at the Rock of Gibraltar, “Welcome back to the war.”

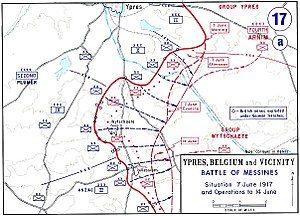

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

On June 7, 1917, they were ready to carry out their secret attack. The explosions created 19 large craters. It would be a crushing victory over the Germans who had no idea of the impending disaster they were about to face. This attack would mark the successful beginning of an Allied offensive designed to break the grinding stalemate on the Western Front in World War I. The time of the attack was set for 3:10am. Precisely on schedule, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The blast from the detonation of all those landmines was heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

Although Messines Ridge battle was, itself was a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect on the German morale. The Germans were forced to retreat to the east, a sacrifice that marked the beginning of their gradual, but continuous loss of territory on the Western Front. It also secured the right flank of the British thrust towards the highly contested Ypres region, which was the eventual objective of the planned offensive. Over the next month and a half, British forces continued to push the Germans back toward the high ridge at Passchendaele, which on July 31 saw the launch of the British offensive known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The Battle of Messines marked the high point of mine warfare. On August 10, 1917, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.

The explosions left a mine crater 40 feet deep. The attack had done its job. Still, after the war was over, the crater remained, and some wanted to change the “feel” of the place. Nowadays, this mine crater is a serene, contemplative place. I’m sure that many who visit there feel the significance of the location, but also know just  how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

One of the weapons of naval warfare that all of us know about is the torpedo. Beginning in the 1870’s, torpedoes were rapidly introduced into the navies of many states and soon became the primary weapon of destroyers, submarines, and torpedo boats, cruisers, and ships of the line of that period were also armed with torpedoes. Torpedoes were first used by Russian vessels in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. So torpedoes weren’t new on March 26, 1941, when Italy attacked the British fleet at Souda Bay, Crete, using these new detachable warheads. These torpedoes were different however, and I can only imagine how the men on the deck of the British cruiser must have felt as they watched the streaking torpedo coming toward them.

One of the weapons of naval warfare that all of us know about is the torpedo. Beginning in the 1870’s, torpedoes were rapidly introduced into the navies of many states and soon became the primary weapon of destroyers, submarines, and torpedo boats, cruisers, and ships of the line of that period were also armed with torpedoes. Torpedoes were first used by Russian vessels in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. So torpedoes weren’t new on March 26, 1941, when Italy attacked the British fleet at Souda Bay, Crete, using these new detachable warheads. These torpedoes were different however, and I can only imagine how the men on the deck of the British cruiser must have felt as they watched the streaking torpedo coming toward them.

The difference between the torpedoes of old, and these new torpedoes, was that these were manned torpedoes. No, there weren’t men on the torpedo known as the Chariot.” Nevertheless it was unique. Primarily used to attack enemy ships still in harbor, the Chariots needed “pilots” to “drive” them to their targets…basically a guided missile system…but in a very primitive form. Sitting astride the torpedo on a vehicle that  would transport them both, the pilot would guide the missile as close to the target as possible, then ride the vehicle back, usually to a submarine. The Chariot was an enormous advantage, because before its development, the closest weapon to the Chariot was the Japanese Kaiten–a human torpedo, or suicide bomb, which had obvious drawbacks. I can’t imagine being ordered to pilot that one, but then the Japanese were known for their suicide attacks.

would transport them both, the pilot would guide the missile as close to the target as possible, then ride the vehicle back, usually to a submarine. The Chariot was an enormous advantage, because before its development, the closest weapon to the Chariot was the Japanese Kaiten–a human torpedo, or suicide bomb, which had obvious drawbacks. I can’t imagine being ordered to pilot that one, but then the Japanese were known for their suicide attacks.

The Italian attack was just the first successful use of the Chariot, or any other manned torpedo, although they referred to their version as Maiali, or “Pigs.” On that March day, six Italian motorboats, commanded by Italian naval commander Lieutenant Luigi Faggioni, entered Souda Bay in Crete and planted their Maiali along a British convoy in harbor there. The British cruiser, York was so badly damaged that it had to be beached. The manned torpedo system proved to be the most effective weapon in the Italian naval arsenal, and it was used successfully against the British again in December 1941 at Alexandria, Egypt. Italian torpedoes sank the British battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant, as well as one tanker. They were also used against merchant ships at  Gibraltar and elsewhere.

Gibraltar and elsewhere.

Deeply angered, the British avenged themselves against the Italians, by sinking the new Italian cruiser Ulpio Traiano in the port of Palermo, Sicily, in early January 1943. An 8,500-ton ocean liner was also damaged in the same attack. After the Italian surrender, the use of the manned torpedo continued to be used by both the British, and later the Germans. In fact, Germany succeeded in sinking two British minesweepers off Normandy Beach in July 1944, using their “Neger” torpedoes. These would be the best torpedo, until the guidance systems could be invented.

In 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. From that time forward until 1920, all of Ireland was a part of the British Isles. The British Isles is a geographical term which includes two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and 5,000 small islands, most notably the Isle of Man which has its own parliament and laws. Today, only Northern Ireland remains, as part of the United Kingdom.

In 1536, Henry VIII decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. From that time forward until 1920, all of Ireland was a part of the British Isles. The British Isles is a geographical term which includes two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and 5,000 small islands, most notably the Isle of Man which has its own parliament and laws. Today, only Northern Ireland remains, as part of the United Kingdom.

For the most part, the Irish War of Independence, also called the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla conflict and most of the fighting was conducted on a small scale by the standards of conventional warfare. Although there were some large-scale encounters between the Irish Republican Army and the state forces of the United Kingdom. The Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC), generally known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, was a paramilitary unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the War. It was set up in July 1920 and made up of former British Army officers, most of whom came from Great Britain. Its role was to conduct counter-insurgency operations against  the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Auxiliaries became infamous for their reprisals on civilians and civilian property in revenge for IRA actions, the best known example of which was the burning of Cork city in December 1920. The Black and Tans officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was a force of temporary constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the war. The force was the brainchild of Winston Churchill, then British Secretary of State for War. Recruitment began in Great Britain in late 1919. Thousands of men, many of them British Army veterans of World War I, answered the British government’s call for recruits.

the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Auxiliaries became infamous for their reprisals on civilians and civilian property in revenge for IRA actions, the best known example of which was the burning of Cork city in December 1920. The Black and Tans officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, was a force of temporary constables recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the war. The force was the brainchild of Winston Churchill, then British Secretary of State for War. Recruitment began in Great Britain in late 1919. Thousands of men, many of them British Army veterans of World War I, answered the British government’s call for recruits.

The war continued on and by November 1920, around 300 people had been killed in the conflict. Then, there  was an escalation of violence beginning on Bloody Sunday, November 21, 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated in Dublin in the morning. Then, in retaliation, the afternoon the RIC opened fire on a crowd at a Gaelic football match in the city, killing fourteen civilians and wounding 65. A week later, seventeen Auxiliaries were killed by the IRA in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In retaliation, the British government declared martial law in much of southern Ireland. The centre of Cork City was burnt out by British forces on December 10, 1920. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months, when 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths. Violence in Ulster, especially Belfast, was notable for its sectarian character and its high number of Catholic civilians.

was an escalation of violence beginning on Bloody Sunday, November 21, 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated in Dublin in the morning. Then, in retaliation, the afternoon the RIC opened fire on a crowd at a Gaelic football match in the city, killing fourteen civilians and wounding 65. A week later, seventeen Auxiliaries were killed by the IRA in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In retaliation, the British government declared martial law in much of southern Ireland. The centre of Cork City was burnt out by British forces on December 10, 1920. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months, when 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths. Violence in Ulster, especially Belfast, was notable for its sectarian character and its high number of Catholic civilians.

The Nazi bombers were notorious for their sneaky bomber raid, especially the night bombings. The British decided that it was time for start fighting back. So they came up with the idea of using German speaking individuals to impersonate German air controllers, broadcasting false orders to confuse German fighter pilots. The plan was called Operation Corona, and the scope of the operation was massive, but ironically, it was only made possible because of German-speaking Jewish refugees who had escaped Germany and settled in Britain. What an amazing way for the Jewish refugees to be able to get back at the Nazis for the horrid treatment they had received and that they had escaped thankfully. Now, these refugees were breaking into Luftwaffe radio channels and playing wreaking havoc on the Luftwaffe’s ability to direct their night fighters.

The Nazi bombers were notorious for their sneaky bomber raid, especially the night bombings. The British decided that it was time for start fighting back. So they came up with the idea of using German speaking individuals to impersonate German air controllers, broadcasting false orders to confuse German fighter pilots. The plan was called Operation Corona, and the scope of the operation was massive, but ironically, it was only made possible because of German-speaking Jewish refugees who had escaped Germany and settled in Britain. What an amazing way for the Jewish refugees to be able to get back at the Nazis for the horrid treatment they had received and that they had escaped thankfully. Now, these refugees were breaking into Luftwaffe radio channels and playing wreaking havoc on the Luftwaffe’s ability to direct their night fighters.

On one night in 1943, the British managed to get almost all the German night fighters to fly home, and only one aircraft was lost during that night. Another night, a German night fighter, who was already lost, was redirected to a British airfield and captured. I can’t imagine what was going on in the minds of the commanding officers in charge of the night fighters. Their men were presumably, totally mixed up, and every mission failed to bring the desired result.

For me, the most amazing part has to do with the Jewish involvement. Hitler was so intent on killing the Jewish  people, and in this instance, it was a group of Jewish people who were able to pull of a great victory over Hitler and his night fighter pilots. Operation Corona was made possible because before the war many people, mostly Jews, fled Nazi Germany to England, and I seriously doubt if Hitler ever knew what happened, but those people who were involved knew, and while they were not able to help their own people directly, I’m sure it gave them some satisfaction to know that they were doing their part to fight against the horrible dictator who was responsible for the deaths of so many of their people. Operation Corona gave them the opportunity they needed to do something big to help in ending the war and bringing victory to the Allies, thereby helping many of their own people too.

people, and in this instance, it was a group of Jewish people who were able to pull of a great victory over Hitler and his night fighter pilots. Operation Corona was made possible because before the war many people, mostly Jews, fled Nazi Germany to England, and I seriously doubt if Hitler ever knew what happened, but those people who were involved knew, and while they were not able to help their own people directly, I’m sure it gave them some satisfaction to know that they were doing their part to fight against the horrible dictator who was responsible for the deaths of so many of their people. Operation Corona gave them the opportunity they needed to do something big to help in ending the war and bringing victory to the Allies, thereby helping many of their own people too.