Politics

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

Scapa Flow was a naval base in the Orkney Islands in Scotland. When the German ships arrived, they had full crews and in all, there were more than 20,000 German sailors aboard, the number of sailors was reduced in the ensuing months. When the full fleet was at Scapa Flow, there were 74 ships there during negotiations between the Allies and Germany over a peace treaty that would become Versailles. The discussion was about what to do with the ships, since they didn’t really want Germany to have a full fleet ready, should they decide to wage war again. The French and Italians wanted a portion of the fleet, but the British wanted them destroyed. They were concerned about their own naval superiority, should the ships be distributed among the other Allied nations.

The Germans didn’t want their ships in the hand of their enemies, so Admiral Ludwig von Reuter began to prepare for the scuttling in May 1919, after hearing about the potential terms of the Versailles Treaty. Shortly before the treaty was signed on June 21, Reuter sent the signal to his men. The men began opening flood valves, smashing water pipes, and opening sewage tanks. As the scuttle was taking place, nine German crew members who abandoned ship and attempted to come ashore were shot by British forces. As the ships were being scuttled, the intervening British guard ships were able to beach some of the ships. In all, 52 of the 74 ships were sunk. While he wouldn’t say so out loud, British Admiral Wemyss was delighted that the ships were

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

As events from the past get further and further from the present, it’s easy to forget all about them, and for the younger generations…well, they never knew about them, unless they learned about them in history class. In my opinion and the opinion of many conservatives, one of the greatest presidents of all time, was President Ronald Reagan. As a young man, I’m sure no one would have expected that he would even pe president. He was, after all, an actor, and not a politician. Nevertheless, he stepped out of that role, and became first the governor of California, and later the President of the United States, and it was at a pivotable time in history that he was the president.

As events from the past get further and further from the present, it’s easy to forget all about them, and for the younger generations…well, they never knew about them, unless they learned about them in history class. In my opinion and the opinion of many conservatives, one of the greatest presidents of all time, was President Ronald Reagan. As a young man, I’m sure no one would have expected that he would even pe president. He was, after all, an actor, and not a politician. Nevertheless, he stepped out of that role, and became first the governor of California, and later the President of the United States, and it was at a pivotable time in history that he was the president.

Our nation was in the middle of the Cold War, which had really fired up in 1945, at the end of World War II, and continued on until 1991. During that time, we experienced the Iran Hostage Crisis on November 4, 1979, that lasted until January 20, 1981, spanning a total of 444 days. The hostage rescue finally came after President Reagan ordered it, when he became president. He was not afraid to act. He saw something that was unacceptable, and he remedied it…just hours after his inaugural speech. It shouldn’t have taken 444 days to

free these hostages, but until President Reagan stepped in, there was just one attempt, and it failed. The 52 hostages felt forgotten, until President Reagan and the men he sent in, rescued them.

free these hostages, but until President Reagan stepped in, there was just one attempt, and it failed. The 52 hostages felt forgotten, until President Reagan and the men he sent in, rescued them.

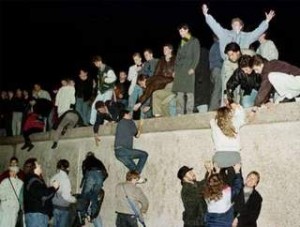

During President Reagan’s two terms in office, he worked tirelessly to change many things for the better. He hated tyranny, no matter what country it invaded. He looked at the Berlin Wall for what it was tyranny. Those people had been taken hostage and separated from their friends and family for long enough. In one of his most well-known speeches, President Reagan called for the tyranny to end, when on June 12, 1987, he challenged Soviet Leader Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall,” which had long been a symbol of the repressive Communist era in a divided Germany. Of course, the wall didn’t come down immediately, and in fact, it wasn’t until November 9, 1989, that it actually came down.

President Reagan was at the helm when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded just 73 seconds after liftoff. It was a tragic event in the space program, and the people of this nation need to be consoled. President Reagan was just the man to give this nation the support it needed. His speech that day was supposed to have been the 1986 State of the Union speech, but President Reagan knew this was more important, so he delayed the State of the Union speech, and instead gave a speech to console us saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, I’d planned to

speak to you tonight to report on the state of the Union, but the events of earlier today have led me to change those plans. Today is a day for mourning and remembering.” He concluded his speech saying, “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.'” President Reagan was truly a great president. President Reagan served two terms as president, from 1981 to 1989. He died on June 5, 2004, at age 93.

speak to you tonight to report on the state of the Union, but the events of earlier today have led me to change those plans. Today is a day for mourning and remembering.” He concluded his speech saying, “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.'” President Reagan was truly a great president. President Reagan served two terms as president, from 1981 to 1989. He died on June 5, 2004, at age 93.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. Because of the horrific things the man known as “Heydrich the Hangman” had done, the Czechoslovakian government-in-exile had decided they needed to get rid of him. The assassination didn’t go quite as planned when the assassin’s gun jammed, but a bomb thrown succeeded, albeit after a few days, caused Heydrich to contract sepsis, which ultimately lead to his death on June 4, 1942.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. Because of the horrific things the man known as “Heydrich the Hangman” had done, the Czechoslovakian government-in-exile had decided they needed to get rid of him. The assassination didn’t go quite as planned when the assassin’s gun jammed, but a bomb thrown succeeded, albeit after a few days, caused Heydrich to contract sepsis, which ultimately lead to his death on June 4, 1942.

There was no evidence that the people of the village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia had anything to do with his death, but that didn’t matter to Hitler. On June 10, 1942, Hitler sent his troops to obliterate the village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia. They had apparently been chosen as the example to all others that killing Hitler’s men was not going to be tolerated. The troops went in and killed all the adult males and deported most of the surviving women and children to concentration camps. The retaliation against these innocent people for something they had no control over, was brutal!! The massacre was carried out just a day after the Nazis rounded up the residents of Lidice, which is located near Prague. During the raid, SS troops herded all the town’s male residents aged 16 years and older…a total of more than 170…to a local farm and gunned them all down. The Germans then shot seven women who tried to run, and deported the remaining women to Ravensbrück concentration camp, which was a women’s slave labor camp. At Ravensbrück about 50 prisoners died, and three were recorded as “disappeared.” Of some 105 children in the village, one was reported shot while trying to run away, and approximately 80 were reported murdered in Chelmno Killing Center, and a handful were reported murdered in German Lebensborn orphanages. A few of the orphans, who were deemed “racially pure” by Nazi standards, were dispersed throughout German territory to be renamed and raised as Germans. After the massacre, SS agents burned Lidice, blew up what was left with dynamite, and leveled the debris. The destruction was to be complete at all costs.

On child, Marie Supikova, a Lidice survivor, was just 9 during the massacre. She tells of the horrible train ride to Poland after her father was executed and her mother was sent to Ravensbrück. “We cried and cried because we were very scared, upset and confused,” Supikova told BBC in a 2012 interview. Because she looked “racially

pure” she was spared. She was sent to a German family living in Poland and had her name changed to Ingeborg Schiller. “We all had blonde hair and blue eyes. We looked like the type that they could German-ize easily and raise as a good German girl or boy,” she said. Today, the Lidice Memorial honors the memory of the victims killed in the totally senseless annihilation of the village of Lidice.

pure” she was spared. She was sent to a German family living in Poland and had her name changed to Ingeborg Schiller. “We all had blonde hair and blue eyes. We looked like the type that they could German-ize easily and raise as a good German girl or boy,” she said. Today, the Lidice Memorial honors the memory of the victims killed in the totally senseless annihilation of the village of Lidice.

My niece, Kayla Stevens is a busy mom of two active daughters, Elliott and Maya. She and Her husband, Garrett have realized that since the birth of their second daughter, their house is too small. Garrett tells me that they are “spilling out at the seams!” So, they have been busy updating everything and fixing things up. Kayla is the visionary in the renovating process. She picks out the paint colors and makes sure things match well and complement each other. They painted the outside of the house last summer and put a rock driveway in making the outside more or less finished. Then, over this past winter, they repainted the living room, hallway, and updated the entire kitchen including cabinets, countertops, and walls. They still have a few more rooms in the basement to finish painting and then they can finish getting the majority of their stuff moved to the storage shed to prepare for the sale of the home.

My niece, Kayla Stevens is a busy mom of two active daughters, Elliott and Maya. She and Her husband, Garrett have realized that since the birth of their second daughter, their house is too small. Garrett tells me that they are “spilling out at the seams!” So, they have been busy updating everything and fixing things up. Kayla is the visionary in the renovating process. She picks out the paint colors and makes sure things match well and complement each other. They painted the outside of the house last summer and put a rock driveway in making the outside more or less finished. Then, over this past winter, they repainted the living room, hallway, and updated the entire kitchen including cabinets, countertops, and walls. They still have a few more rooms in the basement to finish painting and then they can finish getting the majority of their stuff moved to the storage shed to prepare for the sale of the home.

Garrett was telling me the about the distinct differences between him and Kayla. He says, “Kayla is very much a mom. And maybe I think that because I am a dad and it’s very different. She makes all her decisions around the kids. Most of the things she wants to do are things like going to the park or the pool or Playland at the YMCA. If it’s not that, she likes shopping for the kids. She is always finding deals after each season is over. She is a bargain hunter for sure and she is good at it.”

When it comes to travel, Kayla is the travel agent in the family too. She makes sure that their trips will bring the most pleasure each person in the family. They took a trip to WaTiki in Rapid City over spring break with her cousin and her kids. Everyone had a blast, and the kids enjoyed every minute. Kayla is used to travel and planning for travel. Her job with the Veteran’s Administration as an Outreach Coordinator, and her job requires that she travel a lot during the summer. Part of her duties is to work with other groups and organizations. She has traveled to Washington DC several times, and while there she meets with our representatives, or their staff at least, depending on how busy they are. While there, she advocates for legislation to help with mental health and suicide prevention. We all know how important these areas are, because of the ramifications of having untreated individuals with mental health issues and those who are a suicide risk. These people need to be helped, not ignored. The advocates usually get one day with the representatives, and the rest of the trip will consist of conferences to educate them on the latest research and statistics. There is normally very little time for sight-seeing, but the last trip she made, she was able to go and see the sights between events and they enjoyed that. Then, she got stuck there for a few extra days as all the airports were short staffed and having issues. I’m not sure how well she enjoyed that, because she really wanted to get home to her family, but there was no other option. Kayla also makes trips to Jackson Hole, Powell, Pinedale, Gillette, Casper, Dubois, Lander, Cheyenne, and a few others. Over the past year she also made a trip to Arizona and Salt Lake City. In the past, she has also gone to Orlando, as well. She will be going to Oregon in the near future. In

addition, Kayla is working in leadership for the city of Sheridan, as well. She is a very busy girl, but her family is, and always will be her family. She has been blessed to have parents and in-laws who can step in to help with the girls when she has to be away, and Garrett has to work.

addition, Kayla is working in leadership for the city of Sheridan, as well. She is a very busy girl, but her family is, and always will be her family. She has been blessed to have parents and in-laws who can step in to help with the girls when she has to be away, and Garrett has to work.

While her summers are very busy with work and travel, she still makes sure that her family gets to do things too. She and Garrett bought a new camper, and they will be going up to the mountains, the Tongue River Reservoir in Montana, and to Pathfinder Reservoir with his family for the traditional Steven’s Family Summer Camp Out. Kayla leads a busy life, but it makes her happy, and that’s what really matters. Today is Kayla’s birthday. Happy birthday Kayla!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

Under the new law, immigration was to remain open to those with a “college education and/or special skills, but entry was denied disproportionately to Eastern and Southern Europeans and Japanese.” At the same time, the legislation allowed for more immigration from Northern European nations such as Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavian countries. The law also set a quota that limited immigration to two percent of any given nation’s residents already in the US as of 1890, a provision designed to maintain America’s largely Northern European racial composition. In 1927, the “two percent rule” was eliminated and a cap of 150,000 total immigrants annually was established. While this was more fair all around, it particularly angered Japan. In 1907, Japan and US President Theodore Roosevelt had created a “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” which included more liberal immigration quotas for Japan. Of course, that was unfair to other nations looking to send immigrants to the United States. Strong US agricultural and labor interests, particularly from California, had already pushed through a form of exclusionary laws against Japanese immigrants by 1924, so they favored the more restrictive legislation signed by Coolidge.

Of course, the Japanese government felt that the American law as an insult and protested by declaring May 26  a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

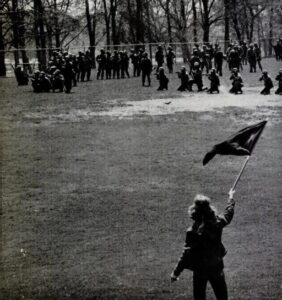

The Vietnam War was a volatile time in American history. When the war started, so did the draft. Many people protested, especially students. I suppose for them, it all felt so much closer to home, than for the older Americans. Still, the students were not alone in protesting. Many Americans agreed and protested too. The law allows for “peaceful” protesting, saying that it is “a constitutionally protected form of expression under the First Amendment in the United States. It falls under the right to free assembly, allowing every American to voice their opinions and advocate for change. However, a protest becomes a riot when one or more people within the group engage in criminal activity. This can include intentionally damaging property or causing physical harm to another person1. In other words, when a peaceful demonstration loses control and turns violent, it transitions from a protest to a riot.”

The Vietnam War was a volatile time in American history. When the war started, so did the draft. Many people protested, especially students. I suppose for them, it all felt so much closer to home, than for the older Americans. Still, the students were not alone in protesting. Many Americans agreed and protested too. The law allows for “peaceful” protesting, saying that it is “a constitutionally protected form of expression under the First Amendment in the United States. It falls under the right to free assembly, allowing every American to voice their opinions and advocate for change. However, a protest becomes a riot when one or more people within the group engage in criminal activity. This can include intentionally damaging property or causing physical harm to another person1. In other words, when a peaceful demonstration loses control and turns violent, it transitions from a protest to a riot.”

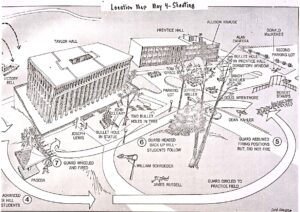

On May 2, 1970, a protest rally at Kent State University resulted in the National Guard troops being called out to suppress students who were now rioting in protest of the Vietnam War and the US invasion of Cambodia. As scattered protests continued the next day, they were dispersed by tear gas, and on May 4th class resumed at Kent State University. University officials put a ban of rallies, but it didn’t stop the rallies. By noon, some 2,000 people had assembled on the campus. The National Guard troops arrived and ordered the crowd to disperse, fired tear gas, and advanced against the students with bayonets fixed on their rifles. As is common among protesters, some refused to disperse, and even responded by throwing rocks and verbally taunting the troops.

As the situation escalated, and without firing a warning shot, 28 Guardsmen discharged more than 60 rounds  toward a group of demonstrators in a nearby parking lot, killing four and wounding nine, one of whom would be permanently paralyzed. The closest casualty was 20 yards away, and the farthest was almost 250 yards away. After a period of disbelief, shock, and attempts at first aid, angry students gathered on a nearby slope and were again ordered to move by the Guardsmen. Though they were prepared to stand and even die for their beliefs, faculty members were able to convince the group to disperse, and further bloodshed was prevented. The Kent State campus was closed for six weeks following the tragedy.

toward a group of demonstrators in a nearby parking lot, killing four and wounding nine, one of whom would be permanently paralyzed. The closest casualty was 20 yards away, and the farthest was almost 250 yards away. After a period of disbelief, shock, and attempts at first aid, angry students gathered on a nearby slope and were again ordered to move by the Guardsmen. Though they were prepared to stand and even die for their beliefs, faculty members were able to convince the group to disperse, and further bloodshed was prevented. The Kent State campus was closed for six weeks following the tragedy.

News of the shootings reverberated across the globe. It also led to protests on college campuses across the country. Just five days after the shootings, 100,000 people demonstrated in Washington, DC, both against the war and the killing of unarmed student protesters. The media put out photographs of the massacre, and the images became enduring images of the anti-war movement. A criminal investigation followed, and in 1974, at the end of the investigation, a federal court dropped all charges levied against eight Ohio National Guardsmen for their role in the Kent State students’ deaths. The decision was followed by outrage.

After the decision was made, the defendants issued a statement, “In retrospect, the tragedy of May 4, 1970, should not have occurred. The students may have believed that they were right in continuing their mass protest in response to the Cambodian invasion, even though this protest followed the posting and reading by the university of an order to ban rallies and an order to disperse. These orders have since been determined by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to have been lawful.

Some of the Guardsmen on Blanket Hill, fearful and anxious from prior events, may have believed in their own  minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

We devoutly wish that a means had been found to avoid the May 4th events culminating in the Guard shootings and the irreversible deaths and injuries. We deeply regret those events and are profoundly saddened by the deaths of four students and the wounding of nine others which resulted. We hope that the agreement to end the litigation will help to assuage the tragic memories regarding that sad day.” I agree, better ways must be found by both the protesters and the authorities.

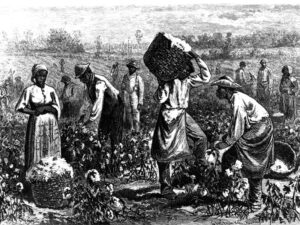

Most of us think that after the Civil War, the South simply accepted defeat and went on to become model citizens of the new America…the one without slavery. That was not the case, however. First of all, there were a number of plantation owners in the South, who just didn’t tell their slaves that they were free now. Finally, after being forced to do so, the announcement came, a whole two months after the effective conclusion of the Civil War, and even longer since Abraham Lincoln had first signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Nevertheless, even after that day, many enslaved black people in Texas still weren’t free. That part was bad enough, but that wasn’t all there was to it.

Most of us think that after the Civil War, the South simply accepted defeat and went on to become model citizens of the new America…the one without slavery. That was not the case, however. First of all, there were a number of plantation owners in the South, who just didn’t tell their slaves that they were free now. Finally, after being forced to do so, the announcement came, a whole two months after the effective conclusion of the Civil War, and even longer since Abraham Lincoln had first signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Nevertheless, even after that day, many enslaved black people in Texas still weren’t free. That part was bad enough, but that wasn’t all there was to it.

We have heard people say that if this or that president gets into office, they are leaving the country. People have also left the country because they didn’t want to fight is a war. However, I had never heard that  approximately 20,000 Confederates decided to actually leave the country. They went to Brazil after the Civil War to create a kingdom built on slavery. These people were so set on their lifestyle that they were willing to pull up stakes and start over in order to keep their slaves and their slavery lifestyle. The reality was that after four bloody years of war, the Confederacy virtually crumbled in April 1865. Nevertheless, a rather large group of the Confederates were not ready to accept defeat.

approximately 20,000 Confederates decided to actually leave the country. They went to Brazil after the Civil War to create a kingdom built on slavery. These people were so set on their lifestyle that they were willing to pull up stakes and start over in order to keep their slaves and their slavery lifestyle. The reality was that after four bloody years of war, the Confederacy virtually crumbled in April 1865. Nevertheless, a rather large group of the Confederates were not ready to accept defeat.

Instead, as many as 20,000 of them fled south. They relocated to Brazil, where a slaveholding culture already existed. There, they hoped the country’s culture could help them preserve their traditions. Once there, they cooked Southern food, spoke English, and tried to buy enough slaves to resurrect the pre-Civil War plantation system. These people, known as Confederados, were enticed to Brazil by offers of cheap land from Emperor Dom Pedro II, who had hoped to gain expertise in cotton farming. Initially, most of these so-called Confederados settled in the current state of São Paulo, where they founded the city of Americana, which was once part of the neighboring city of Santa Bárbara d’Oeste. The descendants of other Confederados would later be found throughout Brazil. They were very happy with their decision to leave the United States, and very

happy that they could continue to keep slaves. Nevertheless, their “victory” was not without loss too. They had to give up their citizenship in the United States, and I have to wonder if their lives have turned out as they hoped they would, or if they are living in much poorer conditions in Brazil. Nevertheless, they stayed, and to this day, the so-called Confederados gather each year to fly the Confederate flag and celebrate their lost heritage.

happy that they could continue to keep slaves. Nevertheless, their “victory” was not without loss too. They had to give up their citizenship in the United States, and I have to wonder if their lives have turned out as they hoped they would, or if they are living in much poorer conditions in Brazil. Nevertheless, they stayed, and to this day, the so-called Confederados gather each year to fly the Confederate flag and celebrate their lost heritage.

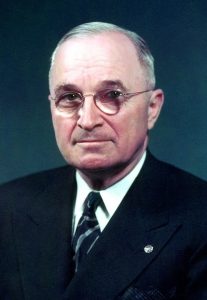

In any “job” or “career” there can be conflicts. Sometimes it’s all about workmanship, and other times it’s a personality conflict. Probably the most famous of these conflicts was the civilian-military confrontation between President Harry S Truman and General Douglas MacArthur who was in command of the US forces in Korea. When Truman relieved MacArthur of duty, in reality, firing him, it set off a brief uproar among the American public. Nevertheless, Truman was determined to keep the conflict in Korea a “limited war” at all costs.

In any “job” or “career” there can be conflicts. Sometimes it’s all about workmanship, and other times it’s a personality conflict. Probably the most famous of these conflicts was the civilian-military confrontation between President Harry S Truman and General Douglas MacArthur who was in command of the US forces in Korea. When Truman relieved MacArthur of duty, in reality, firing him, it set off a brief uproar among the American public. Nevertheless, Truman was determined to keep the conflict in Korea a “limited war” at all costs.

General MacArthur was considered flamboyant and egotistical, and problems between him and President Truman had been brewing for months. The Korean War began in June of 1950, and in those early days of the war in Korea, MacArthur had devised some brilliant strategies and military maneuvers that helped save South Korea from falling to the invading forces of communist North Korea. As United States and United Nations forces began turning the tide of battle in Korea, MacArthur began to argue for a policy of pushing into North Korea to completely defeat the communist forces. Truman initially went along with the plan, but he was also worried that the communist government of the People’s Republic of China might take the invasion as a hostile act and intervene in the conflict. Thus began a battle of wills between the two men. MacArthur met with Truman in October 1950, and assured him that the chances of a Chinese intervention were slim.

Unfortunately, that “slim chance” materialized in November and December 1950, when hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops crossed into North Korea and throwing themselves against the American lines, driving the US troops back into South Korea. At that point, MacArthur requested permission to bomb communist China and use Nationalist Chinese forces from Taiwan against the People’s Republic of China. Truman refused these requests point blank, and a very public and very heated argument began to develop between the two men.

Then, in April 1951, President Truman fired MacArthur and replaced him with General Matthew Ridgway. The nation was outraged, but on April 11, Truman addressed the nation and explained his actions. Truman defended his overall policy in Korea, by declaring, “‘It is right for us to be in Korea.’ He excoriated the ‘communists in the Kremlin [who] are engaged in a monstrous conspiracy to stamp out freedom all over the world.’ Nevertheless, he explained, it ‘would be wrong—tragically wrong—for us to take the initiative in extending the war… Our aim is to avoid the spread of the conflict.’ The president continued, ‘I believe that we must try to limit the war to  Korea for these vital reasons: To make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.’ General MacArthur had been fired ‘so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.'”

Korea for these vital reasons: To make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.’ General MacArthur had been fired ‘so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.'”

Nevertheless, MacArthur returned to the United States to a hero’s welcome. “Parades were held in his honor, and he was asked to speak before Congress (where he gave his famous ‘Old soldiers never die, they just fade away’ speech). Public opinion was strongly against Truman’s actions, but the president stuck to his decision without regret or apology. Eventually, MacArthur did ‘just fade away,’ and the American people began to understand that his policies and recommendations might have led to a massively expanded war in Asia. Though the concept of a ‘limited war,’ as opposed to the traditional American policy of unconditional victory, was new and initially unsettling to many Americans, the idea came to define the U.S. Cold War military strategy.”

Cars are an important part of life these days, and really for many years now. So, what would you do if your ability to buy a car suddenly stopped…like hitting a wall? My guess is that you would start taking really good care of the car you had, because you wouldn’t know how long it would be before you could buy another car. Following the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro imposed a ban on the import of cars from abroad. This made it almost impossible for Cubans to get their hands on new cars, meaning that if they wanted a car, they had to make do and mend the vehicles that were already on the island. Basically, the Cuban people became a nation of mechanics. It was a necessity if they wanted to have a car.

Cars are an important part of life these days, and really for many years now. So, what would you do if your ability to buy a car suddenly stopped…like hitting a wall? My guess is that you would start taking really good care of the car you had, because you wouldn’t know how long it would be before you could buy another car. Following the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro imposed a ban on the import of cars from abroad. This made it almost impossible for Cubans to get their hands on new cars, meaning that if they wanted a car, they had to make do and mend the vehicles that were already on the island. Basically, the Cuban people became a nation of mechanics. It was a necessity if they wanted to have a car.

In a way I find it almost strange that Castro didn’t take away the cars they had, but I guess he wasn’t concerned about them driving, just that he didn’t want any imports from the United States. The problem was

that there are no car manufacturers in Cuba, so the only way to buy a car was to import it. Of course, Castro and any of his chosen people could still import vehicles, just not from the United States. These kinds of things happen between governments, and as usual, it’s the people who suffer, not the government. In this case, I’m not so sure that “suffer” is the right word. Cuba has a huge collection of classic cars, because the people became, not only great mechanics, but they also became experts at restoring and caring for classic cars.

that there are no car manufacturers in Cuba, so the only way to buy a car was to import it. Of course, Castro and any of his chosen people could still import vehicles, just not from the United States. These kinds of things happen between governments, and as usual, it’s the people who suffer, not the government. In this case, I’m not so sure that “suffer” is the right word. Cuba has a huge collection of classic cars, because the people became, not only great mechanics, but they also became experts at restoring and caring for classic cars.

In 2014, after 55 years of not being able to, Cubans these days, are free to import foreign cars again. Unfortunately, the cost is so high that it makes imports impossible for all but the wealthiest members of society. Now you will see some newer cars on the roads, but they tend to be owned by taxi companies or car hire firms.

The general population continues to drive to the old classics that they have driven for the last 55 years. While the cars in Cuba are all old, they do have value. All classic cars do, but those that are as well preserved as the ones in Cuba, might just have more value than their owners really know about…on the open market anyway. Whether they will ever be placed on the open market or not is a different story.

The general population continues to drive to the old classics that they have driven for the last 55 years. While the cars in Cuba are all old, they do have value. All classic cars do, but those that are as well preserved as the ones in Cuba, might just have more value than their owners really know about…on the open market anyway. Whether they will ever be placed on the open market or not is a different story.

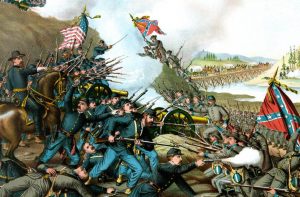

I am of the opinion that most of the United States is populated by good people, who are trying to lead decent and respectful lives. I’m sure there are those who would disagree, and when faced with evil doers, it is sometimes hard to see the good because of the bad, but I think we can agree that the people who agreed with the northern states during the Civil War, far outnumbered those who agreed with the southern states. the Union had a distinctive advantage over the Confederates. There were more states and more soldiers in the Union Army. So, the Confederate Army had to find a way to get ahead of their enemies. Confederates sometimes relied on technical innovation to aid their cause, in the face of such limited resources compared with the Union Army’s sheer numbers and resources. The Union had $234,000,000 in bank deposit and coined money while the Confederacy had $74,000,000 and the Border States had $29,000,000. The Union Army had 2,672,341 soldiers, as opposed to the Confederate Army, which had between 750,000 to 1,227,890 soldiers.

I am of the opinion that most of the United States is populated by good people, who are trying to lead decent and respectful lives. I’m sure there are those who would disagree, and when faced with evil doers, it is sometimes hard to see the good because of the bad, but I think we can agree that the people who agreed with the northern states during the Civil War, far outnumbered those who agreed with the southern states. the Union had a distinctive advantage over the Confederates. There were more states and more soldiers in the Union Army. So, the Confederate Army had to find a way to get ahead of their enemies. Confederates sometimes relied on technical innovation to aid their cause, in the face of such limited resources compared with the Union Army’s sheer numbers and resources. The Union had $234,000,000 in bank deposit and coined money while the Confederacy had $74,000,000 and the Border States had $29,000,000. The Union Army had 2,672,341 soldiers, as opposed to the Confederate Army, which had between 750,000 to 1,227,890 soldiers.

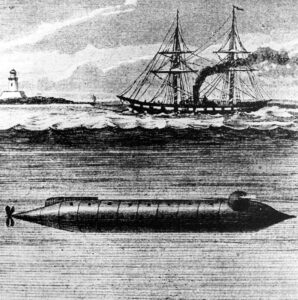

Given the obvious lop-sidedness, especially in the naval conflict, the Confederates could not hope to match the Union in sheer tonnage of ships produced. They didn’t have the funds or the resources to build as many ships as the Union. Many people would actually assume that either the Confederates would lose the war quickly, or it would be mostly fought on land. The Confederates, however, did come up with two famous Confederate naval  innovations…the ironclad warship, CSS Virginia and the submarine, HL Hunley. The HL Hunley was built in 1863. Who would have thought there would be a submarine built that early on.

innovations…the ironclad warship, CSS Virginia and the submarine, HL Hunley. The HL Hunley was built in 1863. Who would have thought there would be a submarine built that early on.

Of course, the Union wasn’t sitting around doing nothing while the Confederates dominated the water. They were busy too. The USS Monitor was built around the same time the Virginia was being retrofitted with iron plating, and those two ships actually clashed at the Battle of Hampton Roads. While the Confederates did get in the war ship game, the superior Northern industrial capacity allowed them to build more than 80 ironclads. The North also built a submarine, called the USS Alligator. It was designed by French engineer Brutus de Villeroi, who had, amazingly, been working on submersible craft for some 30 years. Contrary to what we might think, the concept of a submarine was not a new one. In fact, there was even a primitive one employed in the American War of Independence. The submarines were a far cry from the huge 20th-century submarines of today.

The Alligator was based on an 1859 prototype and was commissioned in 1861 as part of the same flurry of  naval innovation that saw the creation of the ironclad Monitor. The Alligator featured an innovative air-purification system that used limewater to remove carbon dioxide and keep the air breathable for long periods. The Alligator was manned by a 16-member crew, which was later reduced to eight. Also unusual is the fact that USS Alligator had oars to maneuver with. I suppose that wouldn’t seem unusual in its day, but it certainly does today. Sent out on a mission to remove obstructions in Charleston Harbor in advance of an attack by a Union ironclad fleet, the Alligator ran into trouble in the form of a gale on April 2, 1863, while being towed to nearby Port Royal, South Carolina. It was in the storm, and its wreckage was never recovered…but the hunt is ongoing.

naval innovation that saw the creation of the ironclad Monitor. The Alligator featured an innovative air-purification system that used limewater to remove carbon dioxide and keep the air breathable for long periods. The Alligator was manned by a 16-member crew, which was later reduced to eight. Also unusual is the fact that USS Alligator had oars to maneuver with. I suppose that wouldn’t seem unusual in its day, but it certainly does today. Sent out on a mission to remove obstructions in Charleston Harbor in advance of an attack by a Union ironclad fleet, the Alligator ran into trouble in the form of a gale on April 2, 1863, while being towed to nearby Port Royal, South Carolina. It was in the storm, and its wreckage was never recovered…but the hunt is ongoing.