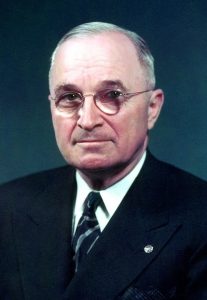

In any “job” or “career” there can be conflicts. Sometimes it’s all about workmanship, and other times it’s a personality conflict. Probably the most famous of these conflicts was the civilian-military confrontation between President Harry S Truman and General Douglas MacArthur who was in command of the US forces in Korea. When Truman relieved MacArthur of duty, in reality, firing him, it set off a brief uproar among the American public. Nevertheless, Truman was determined to keep the conflict in Korea a “limited war” at all costs.

In any “job” or “career” there can be conflicts. Sometimes it’s all about workmanship, and other times it’s a personality conflict. Probably the most famous of these conflicts was the civilian-military confrontation between President Harry S Truman and General Douglas MacArthur who was in command of the US forces in Korea. When Truman relieved MacArthur of duty, in reality, firing him, it set off a brief uproar among the American public. Nevertheless, Truman was determined to keep the conflict in Korea a “limited war” at all costs.

General MacArthur was considered flamboyant and egotistical, and problems between him and President Truman had been brewing for months. The Korean War began in June of 1950, and in those early days of the war in Korea, MacArthur had devised some brilliant strategies and military maneuvers that helped save South Korea from falling to the invading forces of communist North Korea. As United States and United Nations forces began turning the tide of battle in Korea, MacArthur began to argue for a policy of pushing into North Korea to completely defeat the communist forces. Truman initially went along with the plan, but he was also worried that the communist government of the People’s Republic of China might take the invasion as a hostile act and intervene in the conflict. Thus began a battle of wills between the two men. MacArthur met with Truman in October 1950, and assured him that the chances of a Chinese intervention were slim.

Unfortunately, that “slim chance” materialized in November and December 1950, when hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops crossed into North Korea and throwing themselves against the American lines, driving the US troops back into South Korea. At that point, MacArthur requested permission to bomb communist China and use Nationalist Chinese forces from Taiwan against the People’s Republic of China. Truman refused these requests point blank, and a very public and very heated argument began to develop between the two men.

Then, in April 1951, President Truman fired MacArthur and replaced him with General Matthew Ridgway. The nation was outraged, but on April 11, Truman addressed the nation and explained his actions. Truman defended his overall policy in Korea, by declaring, “‘It is right for us to be in Korea.’ He excoriated the ‘communists in the Kremlin [who] are engaged in a monstrous conspiracy to stamp out freedom all over the world.’ Nevertheless, he explained, it ‘would be wrong—tragically wrong—for us to take the initiative in extending the war… Our aim is to avoid the spread of the conflict.’ The president continued, ‘I believe that we must try to limit the war to  Korea for these vital reasons: To make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.’ General MacArthur had been fired ‘so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.'”

Korea for these vital reasons: To make sure that the precious lives of our fighting men are not wasted; to see that the security of our country and the free world is not needlessly jeopardized; and to prevent a third world war.’ General MacArthur had been fired ‘so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy.'”

Nevertheless, MacArthur returned to the United States to a hero’s welcome. “Parades were held in his honor, and he was asked to speak before Congress (where he gave his famous ‘Old soldiers never die, they just fade away’ speech). Public opinion was strongly against Truman’s actions, but the president stuck to his decision without regret or apology. Eventually, MacArthur did ‘just fade away,’ and the American people began to understand that his policies and recommendations might have led to a massively expanded war in Asia. Though the concept of a ‘limited war,’ as opposed to the traditional American policy of unconditional victory, was new and initially unsettling to many Americans, the idea came to define the U.S. Cold War military strategy.”

Leave a Reply