History

Many people who love the era of the Cowboys and Indians, also find themselves intrigued by the Mountain Men. These men were the epitome of the “wild” west. The Mountain Men were often what many might call “social rejects,” because they lived in the wilderness, hunted and fished to sustain themselves, and were often trappers who sold their furs to supplement their living. All that seems rather normal, but they were also reclusive, and often had long hair and a bushy beard. I suppose that many people would think that our opinion of the mountain men was discriminatory, but we have always had some concerns over those who were so very different. Maybe we even associated the mountain men with lawlessness. They often lived in the wilderness, because the were non-conformists when it came to the law. It wasn’t that they wanted to rob banks and kill people, but rather that they wanted to be free to live their lives the way they saw fit, without all the rules and regulations of society.

Many people who love the era of the Cowboys and Indians, also find themselves intrigued by the Mountain Men. These men were the epitome of the “wild” west. The Mountain Men were often what many might call “social rejects,” because they lived in the wilderness, hunted and fished to sustain themselves, and were often trappers who sold their furs to supplement their living. All that seems rather normal, but they were also reclusive, and often had long hair and a bushy beard. I suppose that many people would think that our opinion of the mountain men was discriminatory, but we have always had some concerns over those who were so very different. Maybe we even associated the mountain men with lawlessness. They often lived in the wilderness, because the were non-conformists when it came to the law. It wasn’t that they wanted to rob banks and kill people, but rather that they wanted to be free to live their lives the way they saw fit, without all the rules and regulations of society.

One such mountain man, was Joe Meek, who was born in Virginia in 1810. Meek was a friendly and relentlessly good-humored young man. Unfortunately, Meek did not have a the same interest in school, that he did to be a friendly, funny guy. In reality, his biggest problem was that he had too much energy to sit still and learn. After finally giving up on schooling, at 16 years old, Meek moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Meek later found a need to read and write, and so taught himself, but his spelling and grammar were said to be “highly original” throughout his life.

In early 1829, Meek joined William Sublette’s ambitious expedition to begin fur trading in the Far West. This was the perfect lifestyle for Meek, and he found himself flourishing. Meek traveled throughout the West for the next decade, thoroughly enjoying the adventure and independence of the mountain man life. Meek was an average man, standing 6 feet 2 inches tall. He wore a heavy beard, and became a favorite character at the annual mountain-men rendezvous, where he regaled his companions with humorous and often exaggerated stories of his wilderness adventures. Meek, who was a well known grizzly hunter, claimed he liked to “count coup” on the dangerous animals before killing them, a variation on a Native American practice in which they shamed a live human enemy by tapping them with a long stick. Meek also claimed to have wrestled an attacking grizzly with his bare hands, before finally sinking a tomahawk into its brain. I suppose it might have been a tall tale, but more than one mountain man hs fought a bear. Some have won, and some have not had the same outcome…sadly.

Meek may have been a misfit in society, but he had good relations with many Native Americans, and in fact, he married three Indian women during his lifetime, including the daughter of a Nez Perce chief. Still, that good relationship didn’t prevent him from getting into some squabbles with the tribes. Many of the Indians didn’t like the incursion of the mountain men into their territories, and periodically, things got hostile. In the spring of 1837, Meek was nearly killed by a Blackfeet warrior who was taking aim with his bow while Meek tried to reload his Hawken rifle. Luckily for Meek, the warrior dropped his first arrow while drawing the bow, and the mountain man had time to reload and shoot.

Finally, in 1840, Meek saw that the golden era of the free trappers was ending. He decided that it was time for a “career change.” Meek and another mountain man, along with Meek’s third wife guided one of the first wagon trains to cross the Rockies on the Oregon Trail. Once there, Meek settled in the lush Willamette Valley of western Oregon, became a farmer, and actively encouraged other Americans to join him. He could see that  times were changing. In 1847, Meek led a delegation to Washington DC, asking for military protection from Indian attacks and territorial status for Oregon. After the long journey, Meek arrived in Washington DC “ragged, dirty, and lousy.” Nevertheless, he became something of a celebrity in the capitol…maybe a little bit like “Crocodile Dundee.” Meek was a novelty, and the Easterners relished the boisterous good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” The trip was quite successful, and Congress responded by making Oregon an official American territory and Meek became a US marshal.

times were changing. In 1847, Meek led a delegation to Washington DC, asking for military protection from Indian attacks and territorial status for Oregon. After the long journey, Meek arrived in Washington DC “ragged, dirty, and lousy.” Nevertheless, he became something of a celebrity in the capitol…maybe a little bit like “Crocodile Dundee.” Meek was a novelty, and the Easterners relished the boisterous good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” The trip was quite successful, and Congress responded by making Oregon an official American territory and Meek became a US marshal.

Strangely, considering his anti-social beginnings, Meek returned to Oregon and became heavily involved in politics, eventually helping to found the Oregon Republican Party. He later retired to his farm, where he died on June 20, 1875 at the age of 65.

These days, we are all used to having a female doctor taking care of us. Those who haven’t are, nevertheless, not opposed to it. Others really don’t want a male doctor. It’s not a gender issue exactly, but there are women who just don’t feel comfortable with a male doctor, and men who don’t feel comfortable with a female doctor. We might have thought that this would not still be an issue all these years later, but it can be. As long as people are uncomfortable with their bodies, this might be the case.

These days, we are all used to having a female doctor taking care of us. Those who haven’t are, nevertheless, not opposed to it. Others really don’t want a male doctor. It’s not a gender issue exactly, but there are women who just don’t feel comfortable with a male doctor, and men who don’t feel comfortable with a female doctor. We might have thought that this would not still be an issue all these years later, but it can be. As long as people are uncomfortable with their bodies, this might be the case.

In the 1800s, however, this was not just an issue of discomfort, it was just not done. Mary E Walker was born in 1832, in Oswego Town near Oswego, New York. She was never one, to “hide her light,” but rather always stood out in a crowd. Even as a child, she was distinguished for her strength of mind and her decision of character. She grew into a very independent woman. Mary wanted to be useful. She had no desire to sit at home and be “just a housewife.” Mary was a feminist before most people knew what that was. She always had great energy, and in her early years, she wore bloomers, the pantaloon style garb of the radical feminists of the age. She decided to go to medical school, and when she graduated in 1855, she was the only female in her class from Syracuse Medical College. After graduation, she became one of the few women physicians in the country.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Dr Walker, who was 29 years old by then, journeyed to Washington DC and applied for an appointment as an Army surgeon. Of course, the Medical Department was…shocked, to put it mildly, and they quickly rejected her…with considerable verbosity. “A woman’s place is in the home,” or “No one will go to a woman doctor!” Dr Walker was not a woman who could be so easily discouraged. She stayed in Washington, and even served as an unpaid volunteer in various camps. Who would do that, and how did she survive without pay. Then, when the patent office was converted into a hospital, Walker served as assistant surgeon…again, without pay. During her time in the patent-office-turned-hospital, she was instrumental in establishing an organization that aided needy women who came to Washington to visit wounded relatives. It was a need that no one really thought about until she did, and it was probably reminiscent on the modern-day Ronald McDonald House.

As good as she was, Walker was not immune to considerable amounts of abuse over her persistent demands to be made a surgeon. Still, they could not dispute the fact that she also earned considerable respect for her many good works. It was about this time that she decided to abandon the bloomers and adopt a modified version of male attire, with a calf length skirt worn over trousers. She kept her hair relatively long and curled  so that anyone could know she was a woman. While she wore a modified version of men’s clothes, she wanted everyone to know that she was a woman. She would not mask her talents by pretending to be a man.

so that anyone could know she was a woman. While she wore a modified version of men’s clothes, she wanted everyone to know that she was a woman. She would not mask her talents by pretending to be a man.

Finally, in November 1862, Dr Mary E Walker presented herself at the Virginia headquarters of MG Ambrose Burnside, and was taken on as a field surgeon. She was still a volunteer, but she was a titled surgeon. She treated the wounded at Warrenton and in Fredericksburg in December 1862. Almost a year later, she was in Chattanooga, Tennessee, tending the casualties of the battle of Chickamauga. After the battle, she again requested a commission as an Army doctor, such a simple thing after her years of loyal service, I would think. In September 1863, MG George H Thomas appointed her as an assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland, assigning her to the 52nd Ohio Regiment. Finally, she had her commission. Now, many stories were told of her bravery under fire. Suddenly, it was ok to talk about just how incredible she was.

Sadly, she served with the 52nd Ohio Regiment for only a short time. In April 1864, Walker was captured by Confederate troops. She had stayed behind to tend wounded following a Union retirement. The Confederates charged her with being a spy and arrested her. The spy accusation came about as a result of her male attire. They said it constituted the principal evidence against her. Dr Walker spent the next four months in various prisons, being subjected to much abuse for her “unladylike” occupation and attire, until she was exchanged for a Confederate surgeon in August 1864.

In October of the same year, the Medical Department granted Dr Walker a contract as an acting assistant surgeon. Finally, 3 years after she first showed up on their doorstep she was given the rank and pay she deserved. Still, despite her requests for battlefield duty, she was not sent into the field again. She spent the rest of the war as superintendent at a Louisville, Kentucky, female prison hospital and a Clarksville, Tennessee orphanage. After she was released from her government contract at the end of the war, Walker lobbied for a brevet promotion to major for her services. Typically, Secretary of War Stanton would not grant the request. Finally, President Andrew Johnson asked for another way to recognize her service. A Medal of Honor was presented to Dr Walker in January 1866. She wore it every day for the rest of her life. She continued in the women’s rights movement and also crusaded against immorality, alcohol and tobacco, and for clothing and election reform. One of her more unusual positions was that there was no need for a women’s suffrage act, as women already had the vote as American citizens. Her taste in clothes never changed, and caused her frequent arrests on such charges as impersonating a man. At one trial, she asserted her right to, “Dress as I please in free America on whose tented fields I have served for four years in the cause of human freedom.” The judge  dismissed the case and ordered the police never to arrest Dr Walker on that charge again. She left the courtroom to hearty applause.

dismissed the case and ordered the police never to arrest Dr Walker on that charge again. She left the courtroom to hearty applause.

In 1916, Congress revised the Medal of Honor standards to include only actual combat with an enemy. Several months later, in 1917, the Board of Medal Awards, after reviewing the merits of the awardees of the Civil War awards, ruled Dr Walker’s medal, as well as those of 910 other recipients, as unwarranted and revoked them. It was an insult of the highest degree, and even after her death on February 21, 1919 at the age of 86, it was not to be forgotten. Nearly 60 years after her death, one of her descendants urged the Army Board for Correction of Military Records to review the case. On June 19, 1977, Army Secretary Clifford Alexander approved the recommendation to restore the Medal of Honor to Dr Mary E Walker. It was the right thing to do. Walker remains the sole female recipient of the Medal of Honor.

During the evil reign of the Nazi regime, we saw leaders of occupied nations being replaced by a Nazi official, who was in agreement with Hitler on the way things should be run. The deposed leader was then exiled, or worse yet, murdered. In September 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, a high-ranking Nazi official and a primary architect of the holocaust, was named Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia (formerly Czechoslovakia). He wasted no time in declaring martial law, and then began executing political prisoners and intelligentsia, and deported the sizable Czech Jewish community. During this time, the Czech government had been exiled to London, but they could not stand what was happening to their countrymen, so they decided to assassinate Heydrich…and so, Operation Anthropoid was born.

During the evil reign of the Nazi regime, we saw leaders of occupied nations being replaced by a Nazi official, who was in agreement with Hitler on the way things should be run. The deposed leader was then exiled, or worse yet, murdered. In September 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, a high-ranking Nazi official and a primary architect of the holocaust, was named Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia (formerly Czechoslovakia). He wasted no time in declaring martial law, and then began executing political prisoners and intelligentsia, and deported the sizable Czech Jewish community. During this time, the Czech government had been exiled to London, but they could not stand what was happening to their countrymen, so they decided to assassinate Heydrich…and so, Operation Anthropoid was born.

Two Czech agents, Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik, had undergone extensive training by British intelligence, and on December 29, 1941, were successfully parachuted into Czechoslovakia. Once on the ground, they had to establish themselves, so they spent six months perfecting a plan with local resistance fighters, who were more

than happy to lend a hand in such an important mission. The plan was perfect. The Reich Protector didn’t think he had anything to fear from the local citizens, whom he assumed were beaten down and obedient. On May 27, 1942, Kubis and Gabcik secretly waited along Heydrich’s usual morning route to the Nazi’s Prague headquarters. Reich Protector Heydrich was an arrogant man, and he boldly rode in an open Mercedes convertible, thinking himself invincible, or at the very least well protected.

than happy to lend a hand in such an important mission. The plan was perfect. The Reich Protector didn’t think he had anything to fear from the local citizens, whom he assumed were beaten down and obedient. On May 27, 1942, Kubis and Gabcik secretly waited along Heydrich’s usual morning route to the Nazi’s Prague headquarters. Reich Protector Heydrich was an arrogant man, and he boldly rode in an open Mercedes convertible, thinking himself invincible, or at the very least well protected.

In an unfortunate turn of events, the machine gun Gabcik pointed at Heydrich, as his vehicle slowed at an L-shaped curve, misfired. Heydrich ordered his driver to stop, planning to shoot Gabcik, but Kubis tossed a  grenade and the Reich Protector’s car, which detonated near the car’s right fender. Both Kubis and Gabcik escaped and Heydrich, who initially thought he was uninjured, died on June 4, 1942. So, in the end the assassination was successful, if not strangely carried out. Unfortunately, not all resistance members are loyal, some can be bought off, and that is what happened in this case. Kubis and Gabcik were betrayed by a resistance member and died heroically, on June 18, 1942, after a gunfight with the Gestapo at a Prague church. While these men ultimately gave their lives for this cause, they were heroes, because the target, Reich Protector Heydrich was assassinated, and that was vital.

grenade and the Reich Protector’s car, which detonated near the car’s right fender. Both Kubis and Gabcik escaped and Heydrich, who initially thought he was uninjured, died on June 4, 1942. So, in the end the assassination was successful, if not strangely carried out. Unfortunately, not all resistance members are loyal, some can be bought off, and that is what happened in this case. Kubis and Gabcik were betrayed by a resistance member and died heroically, on June 18, 1942, after a gunfight with the Gestapo at a Prague church. While these men ultimately gave their lives for this cause, they were heroes, because the target, Reich Protector Heydrich was assassinated, and that was vital.

War is inevitable, it would seem. One nation does something another nation doesn’t like, and before you know it, one is attacking the other. War is a bloody business…most of the time. However, in the case of the war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily, that isn’t what happened. The war was strange in every way, and even started in a strange way. The English Civil War, which was fought between the Royalists and Parliamentarians raged from 1642 to 1651. In that war, Oliver Cromwell, who was born into the middle gentry to a family descended from the sister of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, was instrumental in the outcome. He became an Independent Puritan after undergoing a religious conversion in the 1630s. Cromwell generally agreed with the many Protestant churches of that time period. He was an intensely religious man, and he fervently believed that God was guiding his victories. He was elected Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in 1628 and for Cambridge in the Short (1640) and Long (1640–1649) Parliaments. Cromwell had very specific political beliefs, and when he entered the English Civil Wars, it was on the side of the “Roundheads” or Parliamentarians, nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” He demonstrated his

War is inevitable, it would seem. One nation does something another nation doesn’t like, and before you know it, one is attacking the other. War is a bloody business…most of the time. However, in the case of the war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily, that isn’t what happened. The war was strange in every way, and even started in a strange way. The English Civil War, which was fought between the Royalists and Parliamentarians raged from 1642 to 1651. In that war, Oliver Cromwell, who was born into the middle gentry to a family descended from the sister of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, was instrumental in the outcome. He became an Independent Puritan after undergoing a religious conversion in the 1630s. Cromwell generally agreed with the many Protestant churches of that time period. He was an intensely religious man, and he fervently believed that God was guiding his victories. He was elected Member of Parliament for Huntingdon in 1628 and for Cambridge in the Short (1640) and Long (1640–1649) Parliaments. Cromwell had very specific political beliefs, and when he entered the English Civil Wars, it was on the side of the “Roundheads” or Parliamentarians, nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” He demonstrated his  ability as a commander and was quickly promoted from leading a single cavalry troop to being one of the principal commanders of the New Model Army, playing an important role under General Sir Thomas Fairfax in the defeat of the Royalist or “Cavalier” forces.

ability as a commander and was quickly promoted from leading a single cavalry troop to being one of the principal commanders of the New Model Army, playing an important role under General Sir Thomas Fairfax in the defeat of the Royalist or “Cavalier” forces.

Cromwell fought the Royalists to the edges of the Kingdom of England. In the West of England this meant that Cornwall was the last Royalist stronghold. In 1648, Cromwell pushed on until mainland Cornwall was in the hands of the Parliamentarians. The Royalist Navy was forced to retreat to the Isles of Sicily, which lay off the Cornish coast and were under the ownership of Royalist John Granville. With the Royalists on the Isles of Sicily, and the Parliamentarians in England, the war ended…at least the English Civil War ended. Immediately thereafter…on March 30, 1651, one of history’s longest wars began, between the Netherlands and the Isles of Sicily. It lasted for 335 years and was filled with bitter hatred. Still, not a single person was killed. What kind of war is that? The war that comes closest to what this was, would be  the Cold War. It was called, The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years’ War and many will dispute its existence. It is thought that the “war” ended long before it was officially listed as over, and that the only thing that wasn’t done was to sign a peace treaty, and that one thing extended the war for 335 years without a single shot being fired. That fact made it one of the world’s longest wars, and also a bloodless war. The big problem with the validity of the war was that there was no specific declaration of war. Because of that, no one knew if they needed to negotiate a peace treaty or not. Nevertheless, because they needed to end this war, and because the declaration of a state of war was not officially know to exist, peace was finally declared on April 17, 1987, bringing an end to any hypothetical war that may have been legally considered to exist.

the Cold War. It was called, The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years’ War and many will dispute its existence. It is thought that the “war” ended long before it was officially listed as over, and that the only thing that wasn’t done was to sign a peace treaty, and that one thing extended the war for 335 years without a single shot being fired. That fact made it one of the world’s longest wars, and also a bloodless war. The big problem with the validity of the war was that there was no specific declaration of war. Because of that, no one knew if they needed to negotiate a peace treaty or not. Nevertheless, because they needed to end this war, and because the declaration of a state of war was not officially know to exist, peace was finally declared on April 17, 1987, bringing an end to any hypothetical war that may have been legally considered to exist.

While listening to an audible book about World War II, called “Flak,” I heard one of the men being interviewed by the author for the book say, “History is told by the survivors.” It occurred to me that in most cases, at least in eras gone by, that was the truth. In order to know what really happened, there had to be a survivor. Even today, in an era of DNA, forensic science, black boxes, and phone video, there are events that cannot be definitively explained, and causes that remain a mystery.

While listening to an audible book about World War II, called “Flak,” I heard one of the men being interviewed by the author for the book say, “History is told by the survivors.” It occurred to me that in most cases, at least in eras gone by, that was the truth. In order to know what really happened, there had to be a survivor. Even today, in an era of DNA, forensic science, black boxes, and phone video, there are events that cannot be definitively explained, and causes that remain a mystery.

In World War II, survival was one of the main necessities to properly make an account of events. One might be able to look at pictures an know that the attack was bad, but in order to understand what it meant to fly through flak, someone had to really explain what the flak looked like up close, and tell us how hot it was when it got close enough to put a hole in the fuselage of the plane. We can imagine the fear the soldiers of World War II felt, but only because someone has “painted” a picture of just how bad it was to be pinned down in a foxhole with bombs raining down all around you, and bullets flying past if you tried to get out and run. No amount of  modern technology can explain how a soldier might have felt upon looking at his helmet to find a hole in it where shrapnel pierced it, and the soldier received only a small scratch. All of the “facts” that can be gleaned from the modern technology we have simply can’t tell us about how people felt.

modern technology can explain how a soldier might have felt upon looking at his helmet to find a hole in it where shrapnel pierced it, and the soldier received only a small scratch. All of the “facts” that can be gleaned from the modern technology we have simply can’t tell us about how people felt.

My dad, Allen Spencer was a top turret gunner in a B-17G bomber stationed in Great Ashfield. He told once about the ball turret gunner being shot up, and the desperate and futile effort to save his life. It was something Dad would never forget. The bombers that crashed taking all hands down with them, left no witnesses to tell if it was shot down or had engine trouble. If the plane could be found today, they might be able to guess at the cause of the crash, but it still might not be definitive. As to the soldiers who went missing in action, it was not uncommon for their body never to be found, and so no one could document their death, unless a buddy survived. All of the war stories we have today from World War II were told by the men, and women too, who survived. We know from the ones who witnessed the planes being shot down, blown up, or crashing with engine trouble. On the battlefield, the only witnesses were the other  soldiers in the area, because the civilians had run far from the area.

soldiers in the area, because the civilians had run far from the area.

Even the non-war events of history had to have a “survivor” to tell about the event. It may not have been a violent event, but the Gettysburg Address would never have been known to anyone, if it had been spoken aloud in President Lincoln’s study with no one present. The speech might have been found later, but the depth of it’s meaning might have been completely lost had one witness not been so deeply moved by the speech. I wonder how much history was lost because no one was there to see and then survive to tell about it. It’s something to think about.

How could such a small island, sitting in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, have such a large impact during World War II? Malta is only 95 square miles, the largest of the three islands that make up the Maltese archipelago, and it had a population of 433,082 in 2019, so imagine how small the population was during World War II. Nevertheless, the British Crown Colony of Malta was a strategic location and made a pivotal contribution to the air war in the Mediterranean during World War II. I don’t suppose they wanted to be in such a position, and considering the loss of civilian lives, 1,300 in all, they paid a dear price for the war effort.

How could such a small island, sitting in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, have such a large impact during World War II? Malta is only 95 square miles, the largest of the three islands that make up the Maltese archipelago, and it had a population of 433,082 in 2019, so imagine how small the population was during World War II. Nevertheless, the British Crown Colony of Malta was a strategic location and made a pivotal contribution to the air war in the Mediterranean during World War II. I don’t suppose they wanted to be in such a position, and considering the loss of civilian lives, 1,300 in all, they paid a dear price for the war effort.

With the opening of a new front in North Africa in June 1940, came an increase to Malta’s already considerable value. There were British air and sea forces based on the island, who were able to attack the Axis ships transporting vital supplies and reinforcements from Europe. Winston Churchill called the island an “unsinkable

aircraft carrier.” Of course, Malta was a lot bigger, but it was in the sea, and it did have an air base, so it was like a large aircraft carrier. Churchill’s analogy makes sense in that planes could be dispatched from there and return to there as needed during fighting. General Erwin Rommel, the field command of Axis forces in North Africa, recognized its importance quickly. In May 1941, he warned that “Without Malta the Axis will end by losing control of North Africa.”

aircraft carrier.” Of course, Malta was a lot bigger, but it was in the sea, and it did have an air base, so it was like a large aircraft carrier. Churchill’s analogy makes sense in that planes could be dispatched from there and return to there as needed during fighting. General Erwin Rommel, the field command of Axis forces in North Africa, recognized its importance quickly. In May 1941, he warned that “Without Malta the Axis will end by losing control of North Africa.”

Being a strategic centerpiece did not, guarantee Malta’s safety. In fact, the opposite was the case. Both sides needed Malta, but only the Allies had it, so the Axis nations decided to destroy it. Between 1940 and 1942, Malta faced relentless aerial attacks by the Luftwaffe and Italian Air Force. The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force both fought to defend the island and keep it supplied. Malta was essential to the Allied war effort to disrupt Axis

supply lines to Libya, and also for supplying British armies in Egypt. The German and Italian high commands also realized the danger of a British stronghold so close to Italy. Malta was a danger to the Axis nations, and they were bent on wiping it off the face of the earth. Malta had a target on it, and they began to feel like the shooting range.

supply lines to Libya, and also for supplying British armies in Egypt. The German and Italian high commands also realized the danger of a British stronghold so close to Italy. Malta was a danger to the Axis nations, and they were bent on wiping it off the face of the earth. Malta had a target on it, and they began to feel like the shooting range.

Through the course of the war, Malta was bombed so many times that in the end, that in April 1942, the people of Malta were collectively awarded the George Cross by King George VI, which is the highest award for civilian courage and heroism. It is the only time that an entire nation received such an honor. The award was considered such an honor that the nations flag proudly displays the George Cross.

While Germany was not able to bring home the victory in World War II, they were a formidable enemy early in the war. On April 9, 1940, Nazi Germany launched an invasion into Norway. The initial attack was successful, and the Nazis captured several strategic points on the Norwegian coast. Hitler didn’t care that Norway had declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II. Hitler wanted to rule the world and Norway was part of what he wanted.

While Germany was not able to bring home the victory in World War II, they were a formidable enemy early in the war. On April 9, 1940, Nazi Germany launched an invasion into Norway. The initial attack was successful, and the Nazis captured several strategic points on the Norwegian coast. Hitler didn’t care that Norway had declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II. Hitler wanted to rule the world and Norway was part of what he wanted.

During the preliminary phase of the invasion, Norwegian fascist forces under Vidkun Quisling acted as a so-called “fifth column” for the German invaders, seizing Norway’s nerve centers, spreading false rumors, and occupying military bases and other locations. They were the invaders from within.  Quisling agreed with Hitler concerning the “Jewish problem” and became the leader of Norway during the Nazi occupation. Prior to that Quisling served as the Norwegian minister of defense from 1931 to 1933, and in 1934 he left the ruling party to establish the Nasjonal Samling, or National Unity Party, which was an imitation of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party.

Quisling agreed with Hitler concerning the “Jewish problem” and became the leader of Norway during the Nazi occupation. Prior to that Quisling served as the Norwegian minister of defense from 1931 to 1933, and in 1934 he left the ruling party to establish the Nasjonal Samling, or National Unity Party, which was an imitation of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party.

Norway’s declaration of neutrality didn’t do them much good when their own minister of defense was a traitor. Norway’s declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II, was simply a small stumbling block in the plan Nazi Germany had. Hitler regarded the occupation of Norway a strategic and economic necessity. In the spring of 1940, Vidkun Quisling met with Nazi command in Berlin to plan the German conquest of his country. The Norwegian people have no warning on April 9th, when the combined German forces attacked, and by June 10th Hitler had conquered Norway and driven all Allied forces from the country.

Being the head of the only political party permitted by the Nazis didn’t do Quisling  any good either. The people hated him, and opposition to him in Norway was so great that he couldn’t formally establish his puppet government in Oslo until February 1942. Nevertheless, the regime he set up under the authority of his Nazi commissioner, Josef Terboven, was a repressive regime that was merciless toward those who defied it. There was not peace for either side in those years. Norway’s resistance movement soon became the most effective in all Nazi-occupied Europe, and Quisling’s authority rapidly failed. After the German surrender in May 1945, Quisling was arrested, convicted of high treason, and shot. He was so hated that from his name comes the word quisling, meaning “traitor” in several languages.

any good either. The people hated him, and opposition to him in Norway was so great that he couldn’t formally establish his puppet government in Oslo until February 1942. Nevertheless, the regime he set up under the authority of his Nazi commissioner, Josef Terboven, was a repressive regime that was merciless toward those who defied it. There was not peace for either side in those years. Norway’s resistance movement soon became the most effective in all Nazi-occupied Europe, and Quisling’s authority rapidly failed. After the German surrender in May 1945, Quisling was arrested, convicted of high treason, and shot. He was so hated that from his name comes the word quisling, meaning “traitor” in several languages.

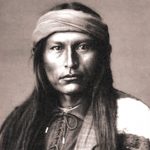

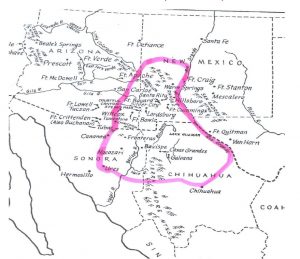

We always think of the wars between the Indians and the White Man being disputes between the two parties over land, and often they were, but sometimes it is something else altogether, and sometimes it is simply ad devastatingly, a mistake. As with many Indians of the early years of our country, not much was known about Chief Cochise’s early life, but he was hailed as one of the great leaders of the Apache Indians. He took them into many battles between his people and the people of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, who he felt were pushing his people off of their lands. Like many other Chiricahua Apache, Cochise resented the encroachment of Mexican and American settlers on their traditional lands. They felt like they had been pushed back and they were tired of it. Cochise began to lead many raids on the settlers living on both sides of the border. The raids caused Mexicans and Americans alike start calling for military aid.

We always think of the wars between the Indians and the White Man being disputes between the two parties over land, and often they were, but sometimes it is something else altogether, and sometimes it is simply ad devastatingly, a mistake. As with many Indians of the early years of our country, not much was known about Chief Cochise’s early life, but he was hailed as one of the great leaders of the Apache Indians. He took them into many battles between his people and the people of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, who he felt were pushing his people off of their lands. Like many other Chiricahua Apache, Cochise resented the encroachment of Mexican and American settlers on their traditional lands. They felt like they had been pushed back and they were tired of it. Cochise began to lead many raids on the settlers living on both sides of the border. The raids caused Mexicans and Americans alike start calling for military aid.

While those raids resulted in deaths and retribution, there was a war that was started for a completely different reason…a misunderstanding. In October 1860, a band of Apache attacked the ranch of John Ward, who was an Irish-American. The Apache kidnapped Ward’s adopted son, Felix Telles. Ward was not home at the time, and while he had no confirmation, he was convinced that Cochise was the leader of the raid. Ward demanded that the US Army go out to rescue his son and bring Cochise to justice. Of course, the Army mobilized immediately, under the command of Lieutenant George Bascom.

Cochise had no idea that they were in any danger, when they received Bascom’s invitation to join him for a night of entertainment at a nearby stage station. I suppose that is was a peaceful way to arrest the warriors,  but it seems so unscrupulous now. Still, I guess no one died that night. When the Apache arrived, Bascom’s soldiers arrested them. Cochise told Bascom that he was innocent of the kidnapping of Felix Telles, but the lieutenant refused to believe him. Bascom decided that Cochise would be kept in confinement until the boy was returned, thinking that his warriors would relent and give up the boy to get their chief back, but Cochise had other ideas. Cochise determined that he would not tolerate being imprisoned unjustly. He used his knife to cut his way out of the tent where he was being held and escaped. They did not recapture Cochise, and the boy was not returned.

but it seems so unscrupulous now. Still, I guess no one died that night. When the Apache arrived, Bascom’s soldiers arrested them. Cochise told Bascom that he was innocent of the kidnapping of Felix Telles, but the lieutenant refused to believe him. Bascom decided that Cochise would be kept in confinement until the boy was returned, thinking that his warriors would relent and give up the boy to get their chief back, but Cochise had other ideas. Cochise determined that he would not tolerate being imprisoned unjustly. He used his knife to cut his way out of the tent where he was being held and escaped. They did not recapture Cochise, and the boy was not returned.

The raids continued and increased in severity over the next decade. Cochise and his warriors also fought occasional skirmishes with soldiers. The unrest started a panic among the settlers, and they began to abandon their homes. The Apache raids took hundreds of lives and caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damages. As time went on the US government was desperate for peace by 1872, so finally the government offered Cochise and his people a huge reservation in the southeastern corner of Arizona Territory, in exchange for the cessation of the hostilities. Cochise agreed, saying, “The white man and the Indian are to drink of the same water, eat of the same bread, and be at peace.” Cochise knew that he needed to help his people transition into a day of peace. Unfortunately, Cochise did not get to enjoy his hard-won peace for very long. He became seriously ill in 1874. It is believed that he quite possibly had stomach cancer. Cochise died on June 8, 1874. That night his warriors painted his body yellow, black, and vermilion, and took him deep into the Dragoon Mountains. They lowered his body and weapons into a rocky crevice, the exact location of which  remains unknown. I don’t know if that is a traditional burial for a chief, or if Cochise was considered special, but to this day that section of the Dragoon Mountains is known as Cochise’s Stronghold.

remains unknown. I don’t know if that is a traditional burial for a chief, or if Cochise was considered special, but to this day that section of the Dragoon Mountains is known as Cochise’s Stronghold.

The war had lasted from 1860 to 1872, and was truly all about the kidnapping of Felix Telles, but about a decade after Cochise died, Felix Telles actually resurfaced. He was alike and well, and was actually an Apache-speaking scout for the US Army. How could they have not known who he was? Nevertheless, they didn’t. He reported that a group of Western Apache, not Cochise, had kidnapped him. That was such a devastating revelation. To know that so many people lost their lives because of a misunderstanding.

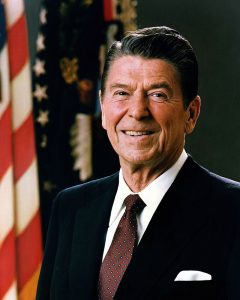

Many people would agree that one of the greatest presidents the United States ever had was Ronald Reagan. He was not what we would consider a career politician, and in fact, most would knw him as an actor long before he was a politician. Nevertheless, after spending time as the President of the Screen Actors’ Guild, where he fought against Communist influence on the screen, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California in 1966. He then became president in 1980, and the rest, as they say is history, but it is not the end.

Many people would agree that one of the greatest presidents the United States ever had was Ronald Reagan. He was not what we would consider a career politician, and in fact, most would knw him as an actor long before he was a politician. Nevertheless, after spending time as the President of the Screen Actors’ Guild, where he fought against Communist influence on the screen, Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California in 1966. He then became president in 1980, and the rest, as they say is history, but it is not the end.

Ronald Reagan would prove to be a very strong person in many areas of his life…some we know of, and some, maybe not…or at least, I didn’t. After college, where Reagan was an average student, and basically considered a “jack of all trades,” he did some work in radio and such until deciding to enlist in the Army Enlisted Reserve. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Officers’ Reserve Corps of the Cavalry on May 25, 1937. On April 18, 1942, Reagan was ordered to active duty, but because of poor eyesight, he was classified for limited service only, which excluded him from serving overseas. His first assignment was at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation at Fort Mason, California, as a liaison officer of the Port and Transportation Office. Upon the approval of the Army Air Forces (AAF), he applied for a transfer from the cavalry to the AAF on May 15, 1942, and was assigned to AAF Public Relations and subsequently to the First Motion Picture Unit (officially, the 18th AAF Base Unit) in Culver City, California. On January 14, 1943, he was promoted to first lieutenant and was sent to the Provisional Task Force Show Unit of “This Is The Army” at Burbank, California. He returned to the First Motion Picture Unit after completing this duty and was promoted to captain on July 22, 1943. While he did not serve in combat, President Reagan was shot. Most of us know that President Reagan survived an assassination attempt on March 30, 1981, when he and his press secretary James Brady were both shot. Also hit by gunfire from would-be assassin John Hinckley Jr outside the Washington Hilton Hotel, were Washington police officer Thomas Delahanty and Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy. President Reagan was “close to death” when he arrived at George Washington University Hospital. He was stabilized in the emergency room, then underwent emergency exploratory surgery. He recovered from his gunshot wound, and was released from the hospital on April 11, becoming the first serving US president to survive being shot in an assassination attempt. President Reagan became very popular after the attempt of his life, with the polls indicating his approval rating to be around 73 percent.

For his part, Reagan believed that God had spared his life so that he “might go on to fulfill a higher purpose.” That is true in my opinion, but it was not the first time Ronald Reagan’s life had been placed at risk. President Reagan attended Dixon High School, where he developed interests in acting, sports, and storytelling, but his first job involved working as a lifeguard at the Rock River in Lowell Park in 1927. He was a life guard there for six years, and during that time, Reagan performed 77 rescues. While much of the rest of his career was highly  public, and well known by most people, this little tidbit was rather hidden in the archives of his life. I suppose many people thought that his job as a lifeguard was a minor role within the many roles he played in his lifetime, but I doubt if the 77 people whose lives he saved as a lifeguard would consider it to be such a minor role. If you have ever been saved from drowning…and I have…you know that you will never forget that person who saved you. I never knew my rescuer’s name, but to this day, I can see her face. I was a girl of about 10 or 12 maybe, and had no training in swimming, but I had achieved the great height of 5 feet, and thought that meant I could swim in the 5 foot area of the pool, not considering that 5 feet was at the top of my head. Thank God for the girl swimming by, who pushed me to the side of the pool. Needless to say, I taught myself to swim after that, and before summer’s end I had passed my swimming test at the pool. What President Reagan did for those 77 people, was as heroic as any soldier. A flailing victim in danger of drowning can take down their would be rescuer, and then both would likely drown. It takes a special person to put their life at risk to save another, and as in many other areas of his life, President Reagan was a true hero.

public, and well known by most people, this little tidbit was rather hidden in the archives of his life. I suppose many people thought that his job as a lifeguard was a minor role within the many roles he played in his lifetime, but I doubt if the 77 people whose lives he saved as a lifeguard would consider it to be such a minor role. If you have ever been saved from drowning…and I have…you know that you will never forget that person who saved you. I never knew my rescuer’s name, but to this day, I can see her face. I was a girl of about 10 or 12 maybe, and had no training in swimming, but I had achieved the great height of 5 feet, and thought that meant I could swim in the 5 foot area of the pool, not considering that 5 feet was at the top of my head. Thank God for the girl swimming by, who pushed me to the side of the pool. Needless to say, I taught myself to swim after that, and before summer’s end I had passed my swimming test at the pool. What President Reagan did for those 77 people, was as heroic as any soldier. A flailing victim in danger of drowning can take down their would be rescuer, and then both would likely drown. It takes a special person to put their life at risk to save another, and as in many other areas of his life, President Reagan was a true hero.

We don’t often think of generals feeling anguish over men lost in the battles they are sent to fight. It’s not that we don’t realize that they feel bad for sending these men into battle, to their possible deaths, even to their probable deaths, because we do. Still, they are the generals, and far above the rank and file…the little guys. Generals, Admirals, the President…could they even realize the consequences of their decisions in the lives of the people under them? I think most of us somehow think that the generals and even the president have no idea how many people they are condemning to death by the orders they give. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

We don’t often think of generals feeling anguish over men lost in the battles they are sent to fight. It’s not that we don’t realize that they feel bad for sending these men into battle, to their possible deaths, even to their probable deaths, because we do. Still, they are the generals, and far above the rank and file…the little guys. Generals, Admirals, the President…could they even realize the consequences of their decisions in the lives of the people under them? I think most of us somehow think that the generals and even the president have no idea how many people they are condemning to death by the orders they give. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth.

General Eisenhower, known as “Ike” was the one with the final say in the D-Day attack that could potentially take the lives of more than 160,000 men, as well as the possible destruction of nearly 12,000 aircraft, almost 7,000 sea vessels. The attack was supposed to take place on June 5, 1944, but the weather was not cooperative. For the attack to work, several factors had to be optimally in favor of the Allies. Nevertheless, these were factors that could not be controlled by humans. Things like the tides, the moon, and the weather. They needed low tide and bright lunar conditions, limiting the possibilities to just a few days each month. The dates for June 1944 were the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh. It was a very small window, and then the weather on the fifth didn’t cooperate either. If the attack was not launched on one  of those dates, Ike would be forced to wait until June 19 to try again. Not only did that mean more deaths because of the German occupation, but keeping the attack secret was harder, the longer they had to wait.

of those dates, Ike would be forced to wait until June 19 to try again. Not only did that mean more deaths because of the German occupation, but keeping the attack secret was harder, the longer they had to wait.

Finally, it looked like June 6, 1944 was going to cooperate. All of his advisors told him that their part was a go. Finally it was time for the final decision…one that belonged only to Eisenhower. He labored over the decision. It was not one where he could decide from his lofty position and never think about it again. He knew that he was sending men to their deaths…to certain death. He couldn’t pass the buck. He couldn’t call a dozen people to see how they felt about it. He had to decide. And so he did. History has argued what his exact words were, some said, “Ok, let ‘er rip.” or “Well, we’ll go” or “All right, we move” or “OK, boys, We will go.” or “We will attack tomorrow.” I don’t suppose it really matters what he said exactly, but rather, it mattered what happened after. We now know that the Allied casualties on June 6 have been estimated at 10,000 killed, wounded, and missing in action. Among those were 6,603 Americans, 2,700 British, and 946 Canadians. It ended with an Allied victory, but it was not without cost…the loss of lives was great. Eisenhower could not “celebrate” the anniversary of D-Day, thinking that it would be like patting himself on the back, but I think that the biggest  picture of the weight that the attack placed on Eisenhower was when he was going to a reunion with the 82nd Airborne Division. Upon seeing him, the men stood, cheering and whistling. Reporter Val Lauder had spoken to him, and later watched the news broadcast of the reunion, when her mother noticed something odd. Says Lauder, “My mother, watching with me, said, ‘He’s crying. Why is he crying?’ I said, ‘He’s looking out at a roomful of men he once thought he could be sending to their death.'” That says it all. Ike didn’t just pull the plug and send those men to their deaths…never giving it another thought. The decision haunted him for years, and quite likely the rest of his life.

picture of the weight that the attack placed on Eisenhower was when he was going to a reunion with the 82nd Airborne Division. Upon seeing him, the men stood, cheering and whistling. Reporter Val Lauder had spoken to him, and later watched the news broadcast of the reunion, when her mother noticed something odd. Says Lauder, “My mother, watching with me, said, ‘He’s crying. Why is he crying?’ I said, ‘He’s looking out at a roomful of men he once thought he could be sending to their death.'” That says it all. Ike didn’t just pull the plug and send those men to their deaths…never giving it another thought. The decision haunted him for years, and quite likely the rest of his life.