History

Our space program has gone through many changes over the years. There have been accidents, losses, victories, and amazing strides in both exploration and the vehicles we use to take these trips. One of the biggest goals was to have a space station so that men and women could live and work in space indefinitely…or at least for long periods of time. On June 29, 1995, the American space shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian space station Mir. This docking formed the largest man-made satellite ever to orbit the Earth…at that time, anyway. We all know that records are meant to be broken.

Our space program has gone through many changes over the years. There have been accidents, losses, victories, and amazing strides in both exploration and the vehicles we use to take these trips. One of the biggest goals was to have a space station so that men and women could live and work in space indefinitely…or at least for long periods of time. On June 29, 1995, the American space shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian space station Mir. This docking formed the largest man-made satellite ever to orbit the Earth…at that time, anyway. We all know that records are meant to be broken.

For a number of years, Russia and the United States had been rivals when it came to the Space Race…as well as many other things, so this joint venture was a really big deal. It was not only about the two rivals working in cooperation together, but it was also the 100th human space mission in American history. It was such a big deal, in fact, that Daniel Goldin, chief of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), called it the beginning of “a new era of friendship and cooperation” between the United States and Russia. The docking was also a big deal to people everywhere, with millions of viewers watching on television, Atlantis blasted off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in eastern Florida on June 27, 1995.

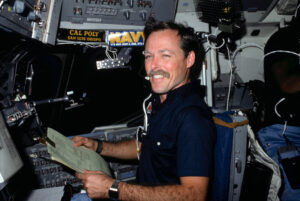

Just after 6am on June 29, the very excited seven-member crew prepared Atlantis for docking with Mir, as both crafts orbited the Earth some 245 miles above Central Asia, near the Russian-Mongolian border. The moment they spotted the shuttle, the three cosmonauts on Mir began to broadcast Russian folk songs to Atlantis to welcome them. The party was about to begin. Over the next two hours, the shuttle’s commander, Robert “Hoot” Gibson expertly maneuvered his craft towards the space station. This was no easy task. In order to make the docking, Gibson had to steer the 100-ton shuttle to within three inches of Mir at a closing rate of no more than one foot every 10 seconds. Now, I don’t know how fast that would be in miles per hour measurement, but I think these crafts could certainly be damaged by the impact. Precision was key.

Well, the docking went perfectly that day, and by 8am it was completed, and just two seconds off the targeted arrival time, while using 200 pounds less fuel than had been anticipated. Now, that’s what I call success. When docked, Atlantis and the 123-ton Mir formed the largest spacecraft ever in orbit at that time. It was only the second time ships from two countries had linked up in space; the first was in June 1975, when an American Apollo capsule and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft briefly joined in orbit.

Once the docking was completed, Gibson and Mir’s commander, Vladimir Dezhurov, greeted each other by clasping hands in a victorious celebration of the historic moment. A formal exchange of gifts followed, with the Atlantis crew bringing chocolate, fruit, and flowers and the Mir cosmonauts offering traditional Russian welcoming gifts of bread and salt. After the party, Atlantis remained docked with Mir for five days before returning to Earth. They left two fresh Russian cosmonauts behind on the space station and took the three veteran Mir crew members home in the shuttle. The returning crew members included two Russians and

Norman Thagard, a US astronaut who rode a Russian rocket to the space station in mid-March 1995 and spent over 100 days in space. This was a United States endurance record…at that time, anyway. This was a great alliance, especially between two former rivals. NASA’s Shuttle-Mir program continued for 11 missions and was a crucial step towards the construction of the International Space Station, which is now in orbit, and is the current largest space craft.

Norman Thagard, a US astronaut who rode a Russian rocket to the space station in mid-March 1995 and spent over 100 days in space. This was a United States endurance record…at that time, anyway. This was a great alliance, especially between two former rivals. NASA’s Shuttle-Mir program continued for 11 missions and was a crucial step towards the construction of the International Space Station, which is now in orbit, and is the current largest space craft.

In a city, there are sometimes people who become the influencers of the community. These people are the ones who shape the city into what it is today. These people are considered the “pillars of the community” and are well liked and respected. Many of the city’s most influential people have streets, parks, and even buildings named after them to honor them.

In a city, there are sometimes people who become the influencers of the community. These people are the ones who shape the city into what it is today. These people are considered the “pillars of the community” and are well liked and respected. Many of the city’s most influential people have streets, parks, and even buildings named after them to honor them.

In Casper, Wyoming, where I live, that “pillar of the community” was a man from Iowa named Samuel W Conwell. Conwell was that “man about town” socialite who was well liked and respected. He really cared about his adopted community, and he helped to shape it into the city it is today. The people of Casper totally agreed that Samuel W Conwell was an amazing influencer in Casper, so they named a 19-block street after him. Conwell Street begins at the East 1st Street intersection where Conwell Park is located. Conwell was born on June 26, 1866, in Iowa, the Hawkeye State, but he moved to Casper around 1895 and immediately began to make his mark on our little town. Over the next four decades, he worked at a number of jobs, including as cashier at the Richards and Cunningham Bank and the Casper National Bank, and later he was the Secretary-Treasurer for the Nicolaysen Lumber Company. Samuel Conwell was a man who wore several hats in his life. He was also an early Casper Fireman.

Some of his other notable milestones achieved while living in and influencing the growth and progress of Casper include serving on high school and district school boards for three decades and helping to build the high school (now known as Natrona County High School, as well as shaping Casper’s educational progress during his time on those boards. Conwell was a county commissioner from 1911-1914. In addition to being a fireman Conwell helped organize the Casper Volunteer Fire Department and then served as its Chief, too. He was the past president of the Casper Chamber of Commerce, and also served as chairman of its traffic committee. In 1921, he was appointed by Governor Carey to the State Highway Commission, where he served the rest of his life. His many contributions to our community, definitely earned him the honors he was later given.

After a long illness, Samuel Conwell died at his home on 241 West 9th Street, on January 31, 1933, at the age of 66. Conwell Street and Conwell Park were not names given randomly by the developer who was just trying to come up with the names, but rather they are names given to represent a pillar of the community, and a man whose spirit lives on in the city.

Seventy-five years ago, people began seeing and having an interest in seeing Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs). A place called Roswell, New Mexico became famous for UFO sightings, and the Air Force found itself denying any sightings. People who saw the UFOs maintained that they “know what they saw!” Roswell, New Mexico is located near the Pecos River in the southeastern part of the state. Roswell became a magnet for UFO believers due to the strange events of early July 1947, when ranch foreman W.W. Brazel found a strange, shiny material scattered over some of his land. It was like nothing he or anyone else had ever seen before.

Seventy-five years ago, people began seeing and having an interest in seeing Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs). A place called Roswell, New Mexico became famous for UFO sightings, and the Air Force found itself denying any sightings. People who saw the UFOs maintained that they “know what they saw!” Roswell, New Mexico is located near the Pecos River in the southeastern part of the state. Roswell became a magnet for UFO believers due to the strange events of early July 1947, when ranch foreman W.W. Brazel found a strange, shiny material scattered over some of his land. It was like nothing he or anyone else had ever seen before.

I’m not one to believe in UFOs, but I must admit that these were unusual sightings. Public interest in Unidentified Flying Objects, or UFOs, began to flourish in the 1940s, when developments in space travel and the dawn of the atomic age caused many Americans to turn their attention to the skies. Brazel turned the material over to the sheriff, who passed it on to authorities at the nearby Air Force base. Not unexpectedly, the Air Force officials announced they had recovered the wreckage of a “flying disk.” A local newspaper put the story on its front page, launching Roswell into the spotlight of the public’s UFO fascination. I’m sure the newspaper was beyond excited to get the story, because a good story is great for selling newspapers…especially when it is unbelievable.

Of course, in typical government style, the Air Force took back their story, saying the debris had been merely a downed weather balloon. After that, the general public lost interest in the UFO, except for the die-hard UFO believers, nicknamed “ufologists.” With that, the “Roswell Incident” faded into oblivion…until the late 1970s. Then, claims surfaced that the military had invented the weather balloon story as a cover-up. Of course, these would be considered the conspiracy theorists of their day. Believers in this theory insisted that officials had retrieved several alien bodies from the crashed spacecraft, which were now stored in the mysterious Area 51 installation in Nevada. Now, the Air Force had clean-up to do. Seeking to dispel these suspicions, the Air Force issued a 1,000-page report in 1994 stating that “the crashed object was actually a high-altitude weather balloon launched from a nearby missile test-site as part of a classified experiment aimed at monitoring the atmosphere in order to detect Soviet nuclear tests.” Then on June 24, 1997, US Air Force officials release a 231-page report dismissing long-standing claims of an alien spacecraft crash in Roswell, New Mexico, almost exactly 50 years earlier.

Many people have heard this story, of course, and Area 51 remains a mystery to many people to this day. Most think that the whole thing was a hoax or a weather balloon, but now…suddenly, NASA has decided to take up the study of UFOs…seriously!! See, that, to me, seems more like a conspiracy theory or at the very least a way to take our minds off of other events going on in our world today, than it is a legitimate search for UFOs or

anything else. According to a story by The Sun, on May 27, 2022, “NASA has reportedly confirmed it will officially join the hunt for UFOs after a groundbreaking UAP Congress hearing earlier this month. Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAPs) and official sightings were recently discussed at a public US Congress hearing on May 17. Nasa had previously said it “does not actively search for” or research UAPs.” What a way to spend our money…and why now, after all these years.

anything else. According to a story by The Sun, on May 27, 2022, “NASA has reportedly confirmed it will officially join the hunt for UFOs after a groundbreaking UAP Congress hearing earlier this month. Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAPs) and official sightings were recently discussed at a public US Congress hearing on May 17. Nasa had previously said it “does not actively search for” or research UAPs.” What a way to spend our money…and why now, after all these years.

In the final years of World War II, both the Allied and Axis Powers knew that there was no chance of defeating Hitler without cracking his grasp on Western Europe, and both sides knew that Northern France was the obvious target for an amphibious assault. Hitler’s army seemed to be everywhere. That said, the Allied forces knew they had to come up with a way to “fool” the leader of the Third Reich. Hitler arrogantly thought that he knew what the Allied forces were planning, and that was the best way to create his downfall. The German high command assumed the Allies would cross from England to France at the narrowest part of the channel and land at Pas-de-Calais. The Allies used that to their advantage and decided on the beaches of Normandy…some 200 miles to the west. The beaches of Normandy could be taken as they were, but if the Germans added to their defense by moving their reserve infantry and panzers to Normandy from their garrison in the Pas-de-Calais region, the invasion would be a disaster.

In the final years of World War II, both the Allied and Axis Powers knew that there was no chance of defeating Hitler without cracking his grasp on Western Europe, and both sides knew that Northern France was the obvious target for an amphibious assault. Hitler’s army seemed to be everywhere. That said, the Allied forces knew they had to come up with a way to “fool” the leader of the Third Reich. Hitler arrogantly thought that he knew what the Allied forces were planning, and that was the best way to create his downfall. The German high command assumed the Allies would cross from England to France at the narrowest part of the channel and land at Pas-de-Calais. The Allies used that to their advantage and decided on the beaches of Normandy…some 200 miles to the west. The beaches of Normandy could be taken as they were, but if the Germans added to their defense by moving their reserve infantry and panzers to Normandy from their garrison in the Pas-de-Calais region, the invasion would be a disaster.

In what would become an ingenious plan, the Allied intelligence services created two fake armies to keep the Germans on their toes. One would wonder how they proposed to pull that off. The Allies created two “Ghost Armies.” One would be based in Scotland to create a supposed invasion of Norway and the other headquartered  in southeast England to threaten the Pas-de-Calais. While the operation in Scotland relied mainly on fake radio traffic and the feeding of false information to double agents to create the impression of a substantial army, the southern “Ghost Army” had to seem much more real. The fortitude South was well within the range of prying German ears and eyes, so fake chatter alone would be uncovered too quickly. It had to look and sound like a substantial army was building up in southeast England. They needed boots on the ground there, without actually using too much of their precious manpower. That seems like a monumental task.

in southeast England to threaten the Pas-de-Calais. While the operation in Scotland relied mainly on fake radio traffic and the feeding of false information to double agents to create the impression of a substantial army, the southern “Ghost Army” had to seem much more real. The fortitude South was well within the range of prying German ears and eyes, so fake chatter alone would be uncovered too quickly. It had to look and sound like a substantial army was building up in southeast England. They needed boots on the ground there, without actually using too much of their precious manpower. That seems like a monumental task.

Enter George and his imaginary men. Patton was put in charge of leading a fake army, commonly known as the “Ghost Army” as part of a massive counterintelligence operation preceding D-Day. The “Ghost Army” was an army of inflatable tanks, rubber airplanes, and fake radio signals designed to trick the German army. The mission was insanely successful. The “Ghost Army” was a United States Army tactical deception unit used during World War II officially known as the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. The 1100-man unit was given a  unique mission within the Allied Army. Their orders…impersonate other Allied Army units to deceive the enemy. It was simple, but it wouldn’t be easy.

unique mission within the Allied Army. Their orders…impersonate other Allied Army units to deceive the enemy. It was simple, but it wouldn’t be easy.

By the evening of June 6, 1944, in what would become known as D-Day, the First Army landed at Normandy. The battle was on, and without the extra troops Hitler might have sent if he wasn’t misled so completely. By June 23, 1945, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops was on its way home after having served with four US armies through England, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. During their tenure, they put on what many would call a “traveling road show” utilizing inflatable tanks, sound trucks, fake radio transmissions, scripts, and pretense. They staged more than 20 battlefield deceptions, often operating very close to the front lines. While their missions and their work were amazing, their story was kept secret for more than 40 years after the war, until it was declassified in 1996.

We all think of California, when we think of Hollywood. Of course, these days we also think of politics, and we wish we didn’t have to associate one with the other, because it has ruined the whole theme of Hollywood. Be that as it may, there was a time when Hollywood wasn’t in California. It was in New York. So, what happened?

We all think of California, when we think of Hollywood. Of course, these days we also think of politics, and we wish we didn’t have to associate one with the other, because it has ruined the whole theme of Hollywood. Be that as it may, there was a time when Hollywood wasn’t in California. It was in New York. So, what happened?

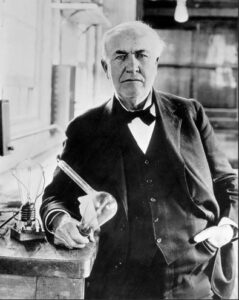

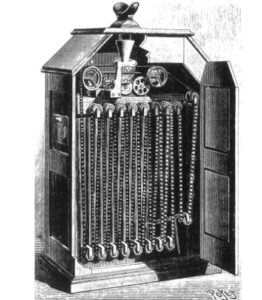

The film industry started in 1878, when Eadweard Muybridge first demonstrated the power of photography to capture motion. It was an amazing new concept, and it started the ball rolling to what would become modern-day films. In 1894, the world’s first commercial motion-picture exhibition was given in New York City. This wouldn’t have been possible without Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope. The kinetoscope is an early motion-picture device in which the images were viewed through a peephole. While Edison’s kinetoscope made film possible, it also became a big part of the problem that caused the film industry to make a major move.

Edison had patented his kinetoscope…as he should have, but in all, he had patents on over 1,000 different things. These patents included most of the technology needed to make high-end movies. The Edison Manufacturing Company’s patent lawsuits against each of its domestic competitors crippled the US film industry. The turmoil reduced production mainly to two companies…Edison and Biograph, which used a different camera design. The others had to import French and British films, which was not how anyone wanted things to go. In the end, Edison pretty much put himself out of the industry.

In the following decades, production of silent film greatly expanded. Studios formed and migrated to California, and films and the stories they told became much longer. The main reason for the move to California was to escape the Edison patent lawsuits, but there were other reasons too. It turned out that the milder climate made it easier to finish films, due to better weather. These days, that doesn’t matter so much. What weather patterns can’t be created, can simply be traveled to, so filming can go on year-round.

In the following decades, production of silent film greatly expanded. Studios formed and migrated to California, and films and the stories they told became much longer. The main reason for the move to California was to escape the Edison patent lawsuits, but there were other reasons too. It turned out that the milder climate made it easier to finish films, due to better weather. These days, that doesn’t matter so much. What weather patterns can’t be created, can simply be traveled to, so filming can go on year-round.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

Knox attended school in Washington DC and graduated from the United States Naval Academy on June 5, 1896. Following his graduation, he served in the Spanish-American War aboard the screw steamer Maple in Cuban waters. A screw steamer or screw steamship is an old term for a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine, using one or more propellers…also known as screws…to propel it through the water. These ships were nicknamed iron screw steam ship.

His was a long and distinguished career. During the Philippine-American War, Knox commanded the gunboat Albay, and during the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, the gunboat Iris. He then commanded three of the Navy’s first destroyers…Shubrick, Wilkes, and Decatur. Following his attendance and graduation from the Naval War College in 1912–13, Knox became the aide to Captain William Sims, commanding the Atlantic Torpedo Flotilla. During the cruise of the “Great White Fleet,” he was sent around the world by President Theodore Roosevelt, as an ordnance officer on the battleship Nebraska (BB-14).

He took the lead in developing naval operational doctrine when he published an article of great influence in the US Naval Institute Proceedings in 1915. He was Fleet Ordnance Officer in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and commanding the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station. The job of a Fleet Ordnance Officers is to ensure that weapons systems, vehicles, and equipment are ready and available…and in perfect working order, at all times. These officers also manage the developing, testing, fielding, handling, storage, and disposal of munitions. In November 1917, Knox joined the staff of, by then, Admiral William Sims, Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters. Knox earned the Navy Cross for “distinguished service” while serving as Aide in the Planning Section and later in the Historical Section. He was promoted to Captain on  February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

Also in 1920, Knox first began his work as a naval publicist, serving as naval editor of the Army and Navy Journal until 1923. He then became the naval correspondent of the Baltimore Sun in 1924 – 1946, and naval correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune in 1929. While he was transferred to the Retired List of the Navy on October 20, 1921, he actually and strangely continued on active duty, serving simultaneously as Officer in Charge, Office of Naval Records and Library, and as Curator for the Navy Department. Knox played a key role in creating the Naval Historical Foundation. Early in World War II, he was assigned additional duty as Deputy Director of Naval History.

In a career that spanned half of a century, Knox’s leadership inspired diligence, efficiency, and initiative while he guided, improved, and expanded the Navy’s archival and historical operations. Knox had personal connections to President Roosevelt, Fleet Admiral Ernest J King, and other senior leaders in the Navy Department. These relationships allowed him to play an instrumental role, albeit behind the scenes in the years leading up to and during World War II.

Knox published a number of writings and several books…including his first book “The Eclipse of American Sea Power” (1922) and “A History of the United States Navy” (1936). “A History of the United States Navy” is recognized as “the best one-volume history of the United States Navy in existence.” Through his personal connection with President Roosevelt, he was able to publish key, multi-volume collections of documents on  naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

November 2, 1945, found Knox promoted to Commodore, and awarded the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious conduct” while directing the correlation and preservation of accurate records of the US naval operations in World War II, thus protecting this vital information for posterity. Finally, on June 26, 1946, Knox was relieved of all active-duty work. He died in Bethesda, Maryland, on June 11, 1960. His cause of death is listed as unknown. He was 83 years old.

People have been eating honey since ancient times. The early connoisseurs of honey weren’t beekeepers, but rather foragers. It stands to reason that at some point people were going to want to have their own supply of honey, and with that beekeeping was born. So, how were they going to have a continuing supply of the honey they loved? Enter the apiary. I didn’t know the meaning of an apiary until my 1st cousin once removed, Larry Cameron got into beekeeping. I had never known anyone who was a beekeeper before, but in my opinion, you would have to be brave to do that job…brave or have the right equipment, I guess.

People have been eating honey since ancient times. The early connoisseurs of honey weren’t beekeepers, but rather foragers. It stands to reason that at some point people were going to want to have their own supply of honey, and with that beekeeping was born. So, how were they going to have a continuing supply of the honey they loved? Enter the apiary. I didn’t know the meaning of an apiary until my 1st cousin once removed, Larry Cameron got into beekeeping. I had never known anyone who was a beekeeper before, but in my opinion, you would have to be brave to do that job…brave or have the right equipment, I guess.

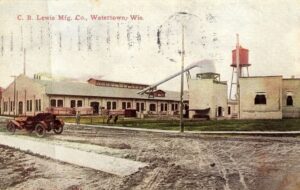

In 1863, a man named G.B. Lewis founded G.B. Lewis Company with the idea of supplying these beekeepers with the necessary beeware to run their businesses. Beeware was a term I really hadn’t heard before, but when I looked it up, it made sense. Beeware, of course, refers to the equipment used by beekeepers. Hives, in 1863, came in three forms…a skep, a log hive, and a box hive. The skep, which was a tightly woven basket, was used the oldest style, but it became obsolete in America, probably because there was plenty of wood to use. G.B. Lewis Company was known for many years as the world’s largest manufacturer of beeware.

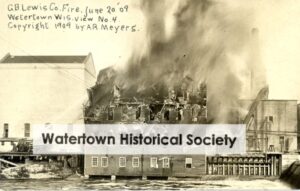

Then on April 25, 1890, disaster struck. At 2:30am on that Saturday morning, a huge fire occurred in the city.  Because the fire was so destructive, it appeared that a large portion of the west side if the city would be destroyed. At G.B. Lewis Company, the entire box, beehive, and section factory was destroyed, along with the Watertown Woolen Mills, owned by Mrs James Chapman. The damage to the G.B. Lewis Company was about $15,000, but it was only insured for $4,500, and at that time there was no guaranteed replacement. Next door to the G.B. Lewis Company and the Watertown Woolen Mills, were two large lumberyards, the Empire flour mills, and several frame buildings. These were apparently saved in the end due to the hard work of the fire department. The origin of the fire is remains unknown to this day.

Because the fire was so destructive, it appeared that a large portion of the west side if the city would be destroyed. At G.B. Lewis Company, the entire box, beehive, and section factory was destroyed, along with the Watertown Woolen Mills, owned by Mrs James Chapman. The damage to the G.B. Lewis Company was about $15,000, but it was only insured for $4,500, and at that time there was no guaranteed replacement. Next door to the G.B. Lewis Company and the Watertown Woolen Mills, were two large lumberyards, the Empire flour mills, and several frame buildings. These were apparently saved in the end due to the hard work of the fire department. The origin of the fire is remains unknown to this day.

Over the years, the distribution of music has taken many forms, and these days most kids would have no idea how to use the vast majority of them. From sheet music that must be played to hear it, to digital music that can be taken with us wherever we go, music is an important part of our lives. Before 1877, sheet music was all there was. If people couldn’t play an instrument or read music, the had to hope they could learn a song by hearing it and learning to replicate it with their own voice. Sometimes that works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Over the years, the distribution of music has taken many forms, and these days most kids would have no idea how to use the vast majority of them. From sheet music that must be played to hear it, to digital music that can be taken with us wherever we go, music is an important part of our lives. Before 1877, sheet music was all there was. If people couldn’t play an instrument or read music, the had to hope they could learn a song by hearing it and learning to replicate it with their own voice. Sometimes that works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

In 1877, an inventor by the name of Thomas Edison came up with a way of recording and playing back audio. The sound quality has changed as much over the years as the vehicle of distribution. The first vehicle for music distribution was a wax cylinder, but that was later changed to a seven-inch disc made from a kind of polyurethane compound by the 1920s. Polyurethane is a type of plastic.

The polyurethane discs worked quite well, but as with most things…improvements can always be made. These new discs brought music to the masses, with record sales reaching around one hundred million in 1927. Then in 1948, the discs became obsolete when the first vinyl records were introduced. There were two versions of the vinyl records, made by two different companies. RCA Company came up with the 45 RPM records, because they thought that the records should hold only one song, while Columbia wanted to be able to have multiple songs in one place, so they came up with the LP 33? RPM which was introduced on June 18, 1948. The vinyl 33? RPM LPs and the cheaper 45 RPM singles remained the dominant format throughout the 1950s.

Like all other forms of technology, vinyl eventually became obsolete when the compact audio cassette came out in 1963. The audiocassette dominated other formats, such as the 8-Track Tape, after the advent of the Sony Walkman in the late 1970s. The Walkman made music portable and within five years, cassette tapes were outselling records. Then, almost like history repeating itself, discs came back into being…this time in the form

of the compact disc (CD). The CD could hold around 80 minutes of music, and after its release in 1982, it quickly became the best way to storing music. By 2007, over two hundred billion CDs had been bought and sold worldwide. Of course, we all know that while you can still buy CDs, they too have been replaced…this time by digital music. Now, I know that I may be the exception in my age group, but I like the digital music, as well as the digital books, and even audio books. It is so much more convenient and takes up much less space.

of the compact disc (CD). The CD could hold around 80 minutes of music, and after its release in 1982, it quickly became the best way to storing music. By 2007, over two hundred billion CDs had been bought and sold worldwide. Of course, we all know that while you can still buy CDs, they too have been replaced…this time by digital music. Now, I know that I may be the exception in my age group, but I like the digital music, as well as the digital books, and even audio books. It is so much more convenient and takes up much less space.

Recently, oil has taken a huge political hit, but most people know that oil is used for far more than the running vehicles. Oil has provided necessary energy to the United States, and even the electric cars can’t exist without petroleum products to make the wiring, tires, seats, floormats, hoses, and much more. In fact, most of us know that there is almost no area of life that isn’t affected by oil. It is part of the makeup of so many things. So, it is silly to think that we can run anything in this world completely void of oil. Living in Wyoming, I know of the value of oil, and many in my family work or have worked in the oil industry.

Recently, oil has taken a huge political hit, but most people know that oil is used for far more than the running vehicles. Oil has provided necessary energy to the United States, and even the electric cars can’t exist without petroleum products to make the wiring, tires, seats, floormats, hoses, and much more. In fact, most of us know that there is almost no area of life that isn’t affected by oil. It is part of the makeup of so many things. So, it is silly to think that we can run anything in this world completely void of oil. Living in Wyoming, I know of the value of oil, and many in my family work or have worked in the oil industry.

Casper, Wyoming has deep roots in the oil industry, and has long provided necessary energy for the nation. Casper’s roots began early on. In 1895, a man named Mark Shannon and a group of Pennsylvania investors opened the state’s first oil refinery in Casper. It was the beginning of an important economic future for Casper and the state. At first, the refinery was able to produce 100 barrels of lubricants per day…not a lot by today’s standards, but in those days, it was phenomenal. Since then, the oil industry has enjoyed a long and successful history, even if the industry did struggle at times. Wyoming is a “Boom-and-Bust” state. We have always been subject to that cycle.

Nevertheless, the early oil fields were quite successful. The Salt Creek and Shannon fields are located in central  Wyoming. With them came the refineries and later, out of necessity, the tank farm oil storage facilities. Storing large quantities of oil, while relatively safe, faces the inevitable possibility of a fire. Safety was always a goal, but it seems an impossible task to stop all fires. The Casper refinery had their first boiler fire on March 5, 1895. Then came the construction of the Casper Tank Farm. According to the Natrona Tribune, reporting on April 18, 1895, “Workmen are now busy sinking a six-hundred-barrel storage reservoir for crude oil and a number of other new tanks and the machinery necessary to finish all grades of oil will be placed as soon as workmen can do so.” I’m sure this was both for storage and safety, but with oil, there is no guarantee.

Wyoming. With them came the refineries and later, out of necessity, the tank farm oil storage facilities. Storing large quantities of oil, while relatively safe, faces the inevitable possibility of a fire. Safety was always a goal, but it seems an impossible task to stop all fires. The Casper refinery had their first boiler fire on March 5, 1895. Then came the construction of the Casper Tank Farm. According to the Natrona Tribune, reporting on April 18, 1895, “Workmen are now busy sinking a six-hundred-barrel storage reservoir for crude oil and a number of other new tanks and the machinery necessary to finish all grades of oil will be placed as soon as workmen can do so.” I’m sure this was both for storage and safety, but with oil, there is no guarantee.

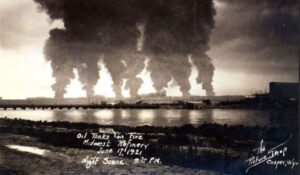

That fact was never made so clear as it was on June 17, 1921, when lightning caused seven oil tanks to catch fire. This became known as the Midwest Oil Tank Farm Battle…and what a battle it was. In those days there was no set plan for fighting a fire in a refinery or a tank farm. It is something you really pray never happens. When lightning struck…in a very real way, they had to figure out how to get it under control, and not lose all of that oil in the tanks. Someone came up with the idea of piercing the tanks below the fire line, thus allowing the oil to drain into the fire dykes. The oil could then be scooped up and pumped into surrounding tanks that were not involved in the fire. It was definitely a great idea, but how were they going to do that?

After giving it some thought, they decided to use some cannons from World War I. The first shot from the cannon hit high, and the oil gushed out toward the men firing the cannon. I’m sure that with the fires around them they must have panicked at least a little bit. These men weren’t firefighters. They were soldiers, so fire was not the enemy they were used to fighting. In all, nine shots were fired that day. One was aimed at a very high angle, and it flew off into areas unknown. Two of them went very low and were buried in the dirt under the tanks. Six shots were right on target. In the end, the operation was successful, and the fire was finally brought under control.

Since tobacco has been proven to cause cancer, its use has declined to a degree, leaving growers, producers, and warehouses in the wake. One such warehouse is The Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool, England. With the decline of tobacco use, the warehouse became a ghost. Of course, it was a warehouse, and could have continued to be useful, but somehow, no one wanted to use it, and it slowly fell into disrepair. The logical solution would have been to tear it down, but since the site is considered a key landmark and World Heritage Site, it can’t be torn down. So, what now?

Since tobacco has been proven to cause cancer, its use has declined to a degree, leaving growers, producers, and warehouses in the wake. One such warehouse is The Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool, England. With the decline of tobacco use, the warehouse became a ghost. Of course, it was a warehouse, and could have continued to be useful, but somehow, no one wanted to use it, and it slowly fell into disrepair. The logical solution would have been to tear it down, but since the site is considered a key landmark and World Heritage Site, it can’t be torn down. So, what now?

The Tobacco Warehouse was built in 1901, and the dream was to build the biggest warehouse the world had ever seen. It was to be a building fit for a  thriving city at the heart of global trade…Liverpool, England. They thought this was going to be a thriving business that would last a lifetime, but they didn’t plan on the fallout from the discovery that tobacco was linked to cancer. Suddenly everyone was quitting, or at least encouraged to do so, and the warehouse was used less and less…and finally not at all.

thriving city at the heart of global trade…Liverpool, England. They thought this was going to be a thriving business that would last a lifetime, but they didn’t plan on the fallout from the discovery that tobacco was linked to cancer. Suddenly everyone was quitting, or at least encouraged to do so, and the warehouse was used less and less…and finally not at all.

Operations at The Tobacco Warehouse stopped in the last portion of the 20th century, and its decline began then. So many old buildings, when they are no longer taken care of, begin to simply fall apart and become a danger to anyone who gets near them. The thing about The Tobacco Warehouse, was  that it wasn’t an ugly building, and it had some amazing views. It was right by the water. In fact, because it was a harbor warehouse, it had the uniqueness of the docks and the view over the water. The whole thing together seemed perfect to create an apartment complex. Of course, it would be something geared toward the young people, artists, and writers, but of course, anyone could rent there as well. They are actually called “hipster lofts.” So, the Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool’s Stanley Dock could become the city’s newest residential hotspot, and all worthy of a Beatle! Most people wouldn’t really consider living in a warehouse, but the industrial look is very popular now, so this is a good fit.

that it wasn’t an ugly building, and it had some amazing views. It was right by the water. In fact, because it was a harbor warehouse, it had the uniqueness of the docks and the view over the water. The whole thing together seemed perfect to create an apartment complex. Of course, it would be something geared toward the young people, artists, and writers, but of course, anyone could rent there as well. They are actually called “hipster lofts.” So, the Tobacco Warehouse in Liverpool’s Stanley Dock could become the city’s newest residential hotspot, and all worthy of a Beatle! Most people wouldn’t really consider living in a warehouse, but the industrial look is very popular now, so this is a good fit.