History

On October 8, 1871, one of the worst fires in history started in Chicago. Rumor has it that a cow kicked over a lantern in a barn, and the ensuing fire killed more than 250 people, left 100,000 homeless, destroyed more than 17,400 structures and burned more than 2,000 acres. According to the legend, the fire broke out after the cow, belonging to Mrs. Catherine O’Leary, kicked over a lamp, setting first the barn, located on the property of Patrick and Catherine O’Leary at 137 Dekoven Street on the city’s southwest side, then the whole city on fire. You’ve probably heard some version of this story yourself. People have been blaming the Great Chicago Fire on the cow and Mrs. O’Leary, for more than 130 years. Mrs. O’Leary denied this charge. Recent research by Chicago historian Robert Cromie has helped to debunk this version of events.

On October 8, 1871, one of the worst fires in history started in Chicago. Rumor has it that a cow kicked over a lantern in a barn, and the ensuing fire killed more than 250 people, left 100,000 homeless, destroyed more than 17,400 structures and burned more than 2,000 acres. According to the legend, the fire broke out after the cow, belonging to Mrs. Catherine O’Leary, kicked over a lamp, setting first the barn, located on the property of Patrick and Catherine O’Leary at 137 Dekoven Street on the city’s southwest side, then the whole city on fire. You’ve probably heard some version of this story yourself. People have been blaming the Great Chicago Fire on the cow and Mrs. O’Leary, for more than 130 years. Mrs. O’Leary denied this charge. Recent research by Chicago historian Robert Cromie has helped to debunk this version of events.

From that event, came a proclamation by President Calvin Coolidge that the first National Fire Prevention Week be held on October 4-10, 1925. The move started a tradition recognizing October as Fire Prevention Month, the first week in October becoming Fire Prevention Week, and the second Saturday becoming Home Fire Drill Day. Fire Prevention Week is observed on the Sunday through Saturday period in which October 9 falls, in commemoration of the Great Chicago Fire, which began October 8, 1871, and did most of its damage October 9. The month and week are filled with information designed to teach people how to prevent fire disasters, as well as activities for children designed to teach them too.

None of us wants to have to really get out of a home fire situation, but it is really important that people know how in the unfortunate event that their home does catch on fire. So, the last part of Fire Prevention Month is Home Fire Drill Day, which is today, October 14, 2017. It is a day to plane your escape routes, and practice

getting out, especially with children. It is designed also, to point out where you might be vulnerable and what equipment might be needed to make your home safe, such as smoke alarms, fire extinguishers, and escape ladders. Whether you have little ones or not, it is so easy to get confused or disoriented in a fire emergency. Just like in the schools, routine practice makes every step of a fire evacuation a habit, and it could very likely save your life or that of your family. Why not start today?

getting out, especially with children. It is designed also, to point out where you might be vulnerable and what equipment might be needed to make your home safe, such as smoke alarms, fire extinguishers, and escape ladders. Whether you have little ones or not, it is so easy to get confused or disoriented in a fire emergency. Just like in the schools, routine practice makes every step of a fire evacuation a habit, and it could very likely save your life or that of your family. Why not start today?

I think most of us have, at one time or another, watched a car race, be it locally, NASCAR, or maybe even street racing…the illegal kind. We might have even raced some ourselves, because when a kid gets behind the wheel of a car, they tend to want to show off a little bit. I suppose it’s the thrill of the race, and feeling the speed of the car beneath you…whether it’s safe or not. Still, most of us don’t tend to get our cars going as fast as the real racecar drivers do. I don’t know about you, but I think that for most of us, going at some of the NASCAR speeds, in real life, is pretty insane. Those drivers are specially trained, and even then, some have been killed or severely injured in bad crashes during those races. As for me, I think I’ll leave the racing to the professionals.

I think most of us have, at one time or another, watched a car race, be it locally, NASCAR, or maybe even street racing…the illegal kind. We might have even raced some ourselves, because when a kid gets behind the wheel of a car, they tend to want to show off a little bit. I suppose it’s the thrill of the race, and feeling the speed of the car beneath you…whether it’s safe or not. Still, most of us don’t tend to get our cars going as fast as the real racecar drivers do. I don’t know about you, but I think that for most of us, going at some of the NASCAR speeds, in real life, is pretty insane. Those drivers are specially trained, and even then, some have been killed or severely injured in bad crashes during those races. As for me, I think I’ll leave the racing to the professionals.

Not all professionals are what you would expect, however. Yesterday, October 11, 2008 marked a very interesting day in the world of speed. On that day, a speed record was set. A man named Luc Costermans, from Belgium set a world speed record driving 192 miles per hour in a borrowed Lamborghini. What? You are sure the record is much higher than that. Well, you would be right, if we are talking about a sighted driver…but, we are not. Luc Costermans is completely blind!! I’m sure that you were as shocked as I was, but let me tell you that he is not the only blind speed racer. Luc Costermans’ record breaking run was performed on a long, straight stretch of airstrip near Marseilles, France. He was accompanied by a carload of sophisticated navigational equipment, as well as a human co-pilot, who gave directions from the Lamborghini’s passenger seat. How fast would you have to be able to give directions to correct a course error for a blind man traveling at 192 miles per hour? Seriously, I don’t know if the co-pilot was very brave, or simply insane!!

To add to the amazing nature of blind speed racing, Costermans is not the first one, and will not likely be the last. The record Costermans broke belonged to Mike Newman, who was a British driver, and who set his record exactly three years to the day before Costermans. Newman had coaxed his 507 horsepower BMW M5 to a top speed of 178.5 mph. For his part, Newman had smashed a 2 year old record 144.7 mph…that he had set himself in a borrowed Jaguar, just three days after he learned to drive. Unlike Costermans, Newman did not race with a co-pilot or a navigator. Instead, he got his father-in-law to zoom around the track behind him, shouting directions over the radio…what??? My mind was racing by this time. Again came the thought of how fast would his father-in-law have to be talking, and then, the thought that his father-in-law was also driving that fast. Was he a racecar driver too? I can’t imagine my father-in-law would have ever driven that fast. He would have asked me if I was insane.

Both of these blind record-setters are serious competitors who race all sorts of vehicles. In 2001, Newman became the fastest blind motorcycle driver in the world, with a record speed of 89 mph, set just four days after learning to ride. Five years later, Costermans flew a small airplane all around France. He was joined by an

instructor and a navigator. Another record-setter, an Englishman named Steve Cunningham, had set the land-speed record himself in 1999, traveling 147 mph, while driving a Chrysler Viper, at the same time that he held the sea-speed record for a blind sailor. In 2004, guided by sophisticated talking navigational software, Cunningham became the first blind pilot to circumnavigate the United Kingdom by air. These men have taken record setting to new levels. I can’t imagine trying these stunts, but then I guess I’m not them.

instructor and a navigator. Another record-setter, an Englishman named Steve Cunningham, had set the land-speed record himself in 1999, traveling 147 mph, while driving a Chrysler Viper, at the same time that he held the sea-speed record for a blind sailor. In 2004, guided by sophisticated talking navigational software, Cunningham became the first blind pilot to circumnavigate the United Kingdom by air. These men have taken record setting to new levels. I can’t imagine trying these stunts, but then I guess I’m not them.

On May 1, 1960, CIA U-2 spy plane pilot, Gary Powers found himself in a lot of trouble. His plane was disabled after being hit by Soviet surface-to-air missiles. Powers had to let his plane fall from 70,000 feet to 30,000 feet before he could release himself and bail out of the damaged cockpit. It was 1960…and the Cold War was heating up. Powers was captured, and would remain a prisoner of war until a prisoner exchange on February 10, 1962. The United States now needed a plane that was safer for these men to fly. Something that went higher and faster than any other plane, and had a minimal radar cross section. It was imperative to have such an innovative aircraft so the United States could improve intelligence gathering. Enter Lockheed’s advanced development group, the Skunk Works® in Burbank. This team had already begun work on such an aircraft.

On May 1, 1960, CIA U-2 spy plane pilot, Gary Powers found himself in a lot of trouble. His plane was disabled after being hit by Soviet surface-to-air missiles. Powers had to let his plane fall from 70,000 feet to 30,000 feet before he could release himself and bail out of the damaged cockpit. It was 1960…and the Cold War was heating up. Powers was captured, and would remain a prisoner of war until a prisoner exchange on February 10, 1962. The United States now needed a plane that was safer for these men to fly. Something that went higher and faster than any other plane, and had a minimal radar cross section. It was imperative to have such an innovative aircraft so the United States could improve intelligence gathering. Enter Lockheed’s advanced development group, the Skunk Works® in Burbank. This team had already begun work on such an aircraft.

President Dwight D Eisenhower was very impressed with the U-2’s airborne reconnaissance during these tense Cold War times, but with the need for better protection for the pilots, Eisenhower’s request went out to Lockheed to build the impossible…an aircraft that can’t be shot down…and do it fast. American aerospace engineer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson was one of the preeminent aircraft designers of the twentieth century. He and his Skunk Works team had a track record of delivering impossible technologies on incredibly short, strategically critical deadlines. Still, everything for this project had to be invented. The group was known for its unfailing sense of duty, its creativity in the face of a technological challenge and its undaunted perseverance. Be that as it may, this new aircraft was in a different category from anything that had come before. This would be the toughest assignment Skunk Works had ever been assigned…at least up to that date. They needed to have the previously unheard of type of aircraft flying in a mere twenty months.

The Lockheed SR-71 “Blackbird” was that long-range, Mach 3+ strategic reconnaissance aircraft, and was operated by the United States Air Force. It was developed as a top secret black project by the Lockheed company. During aerial reconnaissance missions, the SR-71 operated at high speeds and altitudes to allow it to outrace threats. If a surface-to-air missile launch was detected, the standard evasive action was simply to accelerate and outfly the missile. The SR-71 was designed with a reduced radar cross-section, making it harder to spot. The SR-71 served with the U.S. Air Force from 1964 to 1998. A total of 32 aircraft were built. Twelve were lost

in accidents, but none of them to enemy action. The SR-71 has been given several nicknames, including Blackbird and Habu. It has held the world record for the fastest air-breathing manned aircraft since 1976. This record was previously held by the related Lockheed YF-12. On October 9, 1999, the Lockheed SR-71 took it’s final flight, and what a flight it was!! In it’s amazing final flight, the SR-71 Blackbird flew coast to coast in just one hour.

in accidents, but none of them to enemy action. The SR-71 has been given several nicknames, including Blackbird and Habu. It has held the world record for the fastest air-breathing manned aircraft since 1976. This record was previously held by the related Lockheed YF-12. On October 9, 1999, the Lockheed SR-71 took it’s final flight, and what a flight it was!! In it’s amazing final flight, the SR-71 Blackbird flew coast to coast in just one hour.

Obscene language has not always been the norm where language is concerned, and in fact I don’t think most people talked that way even in the not so distant past of the Old West…certainly not in the way Hollywood would have us believe. Those were different times, and to hear the actors dropping the “f bomb” or the “s word” would be…almost laughable if it weren’t for the fact that it should be insulting. I’m not prudish, and I know that things have changed over the years, but when I hear someone cussing at their children, or using cuss words as, just another part of the conversation, I am sometimes shocked and offended. I don’t like to be one of those people who are offended by just everything, but perhaps if we were offended by obscene language, some of the much more shocking things that go on in our world wouldn’t be happening at all. When the Dick Van Dyke Show was on television, the couple had twin beds and the word pregnant couldn’t even be said on television. We all knew that most couples don’t have separate beds or separate rooms, but it went to show the more wholesome, clean cut, decent world we lived in then.

Obscene language has not always been the norm where language is concerned, and in fact I don’t think most people talked that way even in the not so distant past of the Old West…certainly not in the way Hollywood would have us believe. Those were different times, and to hear the actors dropping the “f bomb” or the “s word” would be…almost laughable if it weren’t for the fact that it should be insulting. I’m not prudish, and I know that things have changed over the years, but when I hear someone cussing at their children, or using cuss words as, just another part of the conversation, I am sometimes shocked and offended. I don’t like to be one of those people who are offended by just everything, but perhaps if we were offended by obscene language, some of the much more shocking things that go on in our world wouldn’t be happening at all. When the Dick Van Dyke Show was on television, the couple had twin beds and the word pregnant couldn’t even be said on television. We all knew that most couples don’t have separate beds or separate rooms, but it went to show the more wholesome, clean cut, decent world we lived in then.

By the 1920s, it seemed to begin to be understood that men, anyway, were going to use foul language at times, but they had better watch their mouth in front of the ladies, because it was a law that they not offend those ladylike ears with such harsh words. In fact, on October 8, 1921, a man was charged of speaking offensively in front of a lady and found guilty for using obscene language in front of a woman in Ohio. Now, if you could be fined or sent to spend a few days in jail for using foul language in front of a woman, I think people would be much more likely to watch their tongue. In my parents home, foul language would result in having your mouth washed out with soap. I guess that somehow Mom thought that would clean up the language, and in reality, it did. I don’t say that my sisters and I never used cuss words as teenagers, because everyone goes through rebellious times, but I can tell you that we did not do it in front of our parents, and our boyfriends were told that they had better not talk that way either, if they wanted to continue to date our parents daughter. Cussing was one of the fastest ways for a guy to get on the wrong side of our parents.

These days, it seems that everyone cusses, including children. I hear some of the things coming out of the mouths of little kids, and I almost can’t help having my jaw drop to the floor. Television shows consider some language as being acceptable, and then amazingly they bleep out other words that are not any worse than the ones they have allowed. Obscene gestures are the normal way to tell everyone in sight that you are not happy with what is going on around you, and screaming obscenities is the newest way to express your disgust. Some people have wondered if “swearing is a sign of a limited vocabulary” or is it just a way of “obscenitizing” our world. Either way I find that the loss of eloquent speech is very sad indeed.

When a river is as wide as the Mississippi, and traveling through so many states, often through flat land, the potential for flooding always exists. I know that many people who live along the Mighty Mississippi, would never consider living anywhere else. They love that old river, and having been there myself, I can certainly understand why. The river views are beautiful. Still, the yearly potential for flooding is something that might put many people off, when it comes to living on the shores of that river. Of course, people can get flood insurance, and indeed, most banks would require it for properties along that river, but the possessions lost in floods, not to mention the time it takes to rebuild the homes, and especially the lives lost in floods, make living on the shores of the Mississippi something that I would probably not decide to do.

When a river is as wide as the Mississippi, and traveling through so many states, often through flat land, the potential for flooding always exists. I know that many people who live along the Mighty Mississippi, would never consider living anywhere else. They love that old river, and having been there myself, I can certainly understand why. The river views are beautiful. Still, the yearly potential for flooding is something that might put many people off, when it comes to living on the shores of that river. Of course, people can get flood insurance, and indeed, most banks would require it for properties along that river, but the possessions lost in floods, not to mention the time it takes to rebuild the homes, and especially the lives lost in floods, make living on the shores of the Mississippi something that I would probably not decide to do.

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States,  with 27,000 square miles inundated up to a depth of 30 feet. To try to prevent future floods, the federal government built the world’s longest system of levees and floodways. Of the more than 630,000 people affected by the flood, 94% lived in the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, most in the Mississippi Delta. By August 1927, the flood subsided. Hundreds of thousands of people had been made homeless and displaced…properties, livestock and crops were destroyed. Some people left the area, because they did not have the money, or the stomach for living in an area where their homes could so easily be wiped out. Still, the draw of the beautiful Mississippi kept many people there, determined to rebuild their lives. Of course, the flood didn’t only affect the people living along the Mississippi. Lost crops affected many people in the United States. It was a disaster of epic proportions.

with 27,000 square miles inundated up to a depth of 30 feet. To try to prevent future floods, the federal government built the world’s longest system of levees and floodways. Of the more than 630,000 people affected by the flood, 94% lived in the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, most in the Mississippi Delta. By August 1927, the flood subsided. Hundreds of thousands of people had been made homeless and displaced…properties, livestock and crops were destroyed. Some people left the area, because they did not have the money, or the stomach for living in an area where their homes could so easily be wiped out. Still, the draw of the beautiful Mississippi kept many people there, determined to rebuild their lives. Of course, the flood didn’t only affect the people living along the Mississippi. Lost crops affected many people in the United States. It was a disaster of epic proportions.

Then came the floods of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers in 1993, also known as the Great Flood of 1993. This is one that many of us alive today remember, mostly because we were old enough to remember, but also because the television and newspapers were filled with the stories of destruction. The flood was among the most costly and devastating to ever occur in the United States, with $15 billion in damages. The damage area  was more than 745 miles in length and 435 miles in width, totaling about 320,000 square miles. Within this zone, the flooded area totaled around 30,000 square miles and was the worst such US disaster since the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, as far as duration, area flooded, persons displaced, crop and property damage, and number of record river levels. In some ways, the 1993 flood even surpassed the 1927 flood, which was, at the time, the largest flood ever recorded on the Mississippi River. The effects were felt by people all over the United States because of crops lost, the rise in the cost of building materials, and of course, insurance rates as a result of increased building material prices. Floods are nearly impossible to prevent, and for some people they are considered a risk they are willing to take, but for me, I think I’ll stick to places where the chance of a flood hitting my home is almost nil. On October 7, 1993, the Great Flood of 1993 came to an end as the Mississippi River finally started to recede, 103 days after the flooding began.

was more than 745 miles in length and 435 miles in width, totaling about 320,000 square miles. Within this zone, the flooded area totaled around 30,000 square miles and was the worst such US disaster since the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, as far as duration, area flooded, persons displaced, crop and property damage, and number of record river levels. In some ways, the 1993 flood even surpassed the 1927 flood, which was, at the time, the largest flood ever recorded on the Mississippi River. The effects were felt by people all over the United States because of crops lost, the rise in the cost of building materials, and of course, insurance rates as a result of increased building material prices. Floods are nearly impossible to prevent, and for some people they are considered a risk they are willing to take, but for me, I think I’ll stick to places where the chance of a flood hitting my home is almost nil. On October 7, 1993, the Great Flood of 1993 came to an end as the Mississippi River finally started to recede, 103 days after the flooding began.

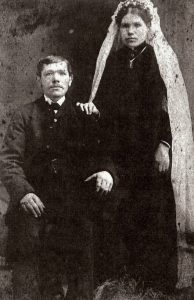

My great grandparents, Henriette and Carl Schumacher were both of German descent. They both came to America at different times…Grandma in 1882 and Grandpa in 1884. They met at a baptism and fell in love. They were married, and had 7 children, one of whom died as a little girl. They were just two of the many German people who have come to this country as far back as the colonial days. Of course, there were many German people who came here before my great grandparents. One of the most notable groups was the 13 German Mennonite families from Krefeld who landed in Philadelphia. These families founded Germantown, Pennsylvania on October 6, 1683. The settlement was the first German establishment in the original thirteen American colonies.

My great grandparents, Henriette and Carl Schumacher were both of German descent. They both came to America at different times…Grandma in 1882 and Grandpa in 1884. They met at a baptism and fell in love. They were married, and had 7 children, one of whom died as a little girl. They were just two of the many German people who have come to this country as far back as the colonial days. Of course, there were many German people who came here before my great grandparents. One of the most notable groups was the 13 German Mennonite families from Krefeld who landed in Philadelphia. These families founded Germantown, Pennsylvania on October 6, 1683. The settlement was the first German establishment in the original thirteen American colonies.

There are many people in the United States who can trace their ancestry back to German roots in one way or another, and the German-American people have been a building block in this nation. These were people who wanted to come here for a better  life, or to escape some of the horrors of the German government, and I for one am thankful that my grandparents immigrated to this country. President Ronald Reagan believed that the German-American heritage was so important to this nation, that in 1983, he proclaimed October 6 as German-American Day to celebrate and honor the 300th anniversary of German American immigration and culture to the United States. On August 6, 1987, Congress approved S.J. Resolution 108, designating October 6, 1987, as German-American Day. It became Public Law 100-104 when President Reagan signed it on August 18, 1987. Proclamation number 5719 was issued on October 2, 1987, by President Reagan in a formal ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, at which time the President called on Americans to observe the Day with appropriate ceremonies and activities. Now for many people, that might include German beer, as well as Oktoberfest activities…basically a party.

life, or to escape some of the horrors of the German government, and I for one am thankful that my grandparents immigrated to this country. President Ronald Reagan believed that the German-American heritage was so important to this nation, that in 1983, he proclaimed October 6 as German-American Day to celebrate and honor the 300th anniversary of German American immigration and culture to the United States. On August 6, 1987, Congress approved S.J. Resolution 108, designating October 6, 1987, as German-American Day. It became Public Law 100-104 when President Reagan signed it on August 18, 1987. Proclamation number 5719 was issued on October 2, 1987, by President Reagan in a formal ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, at which time the President called on Americans to observe the Day with appropriate ceremonies and activities. Now for many people, that might include German beer, as well as Oktoberfest activities…basically a party.

The Germantown, Pennsylvania, settlers organized the first petition in the English colonies to abolish slavery in 1688. Originally known as German Day, the holiday was celebrated for the first time in Philadelphia in 1883, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of the settlers from Krefeld. Similar celebrations developed later in other parts of the country, but the custom died out during World War I as a result of the anti-German sentiment that prevailed at the time. Then, in 1983, President Reagan decided that the time had come to reinstate it. I think it’s a good thing, because those German people who left Germany, were not like the German government was. They were truly good people, who were good for this nation.

The Germantown, Pennsylvania, settlers organized the first petition in the English colonies to abolish slavery in 1688. Originally known as German Day, the holiday was celebrated for the first time in Philadelphia in 1883, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of the settlers from Krefeld. Similar celebrations developed later in other parts of the country, but the custom died out during World War I as a result of the anti-German sentiment that prevailed at the time. Then, in 1983, President Reagan decided that the time had come to reinstate it. I think it’s a good thing, because those German people who left Germany, were not like the German government was. They were truly good people, who were good for this nation.

These days, everyone has heard of the special forces units and special ops, which is special operations. The main reasons we know about them are terrorism, and war in the current world. Special forces and special operations forces are military units trained to conduct the kinds of operations that are often much more dangerous than even the boots on the ground part of battle. NATO defines special operations as “military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, trained, and equipped forces, manned with selected personnel, using unconventional tactics, techniques, and modes of employment”. In other words, these are the guys who go into ugly situations in an effort to keep us safe. Of course, this, in no way, detracts from our first responders, who we all know are just as vital. There is just a difference in the scope of their jobs. The Special Forces emerged in the early 20th century, with a significant growth in the field during the World War II, when “every major army involved in the fighting” created formations devoted to special operations behind enemy lines. It was going to be the only way to win such a war.

These days, everyone has heard of the special forces units and special ops, which is special operations. The main reasons we know about them are terrorism, and war in the current world. Special forces and special operations forces are military units trained to conduct the kinds of operations that are often much more dangerous than even the boots on the ground part of battle. NATO defines special operations as “military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, trained, and equipped forces, manned with selected personnel, using unconventional tactics, techniques, and modes of employment”. In other words, these are the guys who go into ugly situations in an effort to keep us safe. Of course, this, in no way, detracts from our first responders, who we all know are just as vital. There is just a difference in the scope of their jobs. The Special Forces emerged in the early 20th century, with a significant growth in the field during the World War II, when “every major army involved in the fighting” created formations devoted to special operations behind enemy lines. It was going to be the only way to win such a war.

Special Forces teams perform some dangerous functions, including airborne operations, counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, foreign internal defense, covert ops, direct action, hostage rescue, high-value targets/manhunting, intelligence operations, mobility operations, and unconventional warfare. In the United States, Special Forces refers to the US Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine forces. The jobs of the Special Forces units are vital in today’s kind of warfare. Special Forces do reconnaissance and surveillance in hostile environments trying to make it safer to send in the troops. They are in charge of foreign internal defense…training and development of other states’ military and security forces, offensive action, support to counter-insurgency through population engagement and support counter-terrorism operations, sabotage, and demolition, as well as, hostage rescue. They are also used as body guards, in waterborne operations involving combat diving, combat swimming, maritime boarding and amphibious missions, as well as support of air force operations. Special forces have played an important role throughout the history of warfare, whenever the aim was to achieve disruption by “hit and run” and sabotage, rather than more traditional conventional combat. Other significant roles lay in reconnaissance, providing essential intelligence from near or among the enemy and increasingly in combating irregular forces, their infrastructure, and their activities. Originally there were separate units for the different branches of the military, but the need for interoperability between these units from the different services led to the formation US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) in 1987. Our cousin Paul Noyes career in Special Operations was with Ranger, Special Forces and Aviation Special Ops forces, and he has become my military “go to” guy…letting me know if I hit the nail on the head or missed it.

For some reason, I thought Special Forces was, for the most part, a modern day unit, but that isn’t really true. Chinese strategist Jiang Ziya, in his Six Secret Teachings, described recruiting talented and motivated men into specialized elite units with functions such as commanding heights and making rapid long-distance advances. King David had a special forces platoon known as Gibborim. In Japan, ninjas were used for reconnaissance, espionage and as assassins, bodyguards or fortress guards, or otherwise fought alongside conventional soldiers. During the Napoleonic wars, rifle and sapper units were formed that held specialized roles in reconnaissance and skirmishing and were not committed to the formal battle lines. The British Indian Army

deployed two special forces during their border wars…the Corps of Guides formed in 1846 and the Gurkha Scouts…a force that was formed in the 1890s and was first used as a detached unit during the 1897–1898 Tirah Campaign. I guess that the Special Forces units are long standing, expertly trained groups of very special people, who have achieved a level of expertise that is second to none, and I for one, and thankful that such soldiers exist.

deployed two special forces during their border wars…the Corps of Guides formed in 1846 and the Gurkha Scouts…a force that was formed in the 1890s and was first used as a detached unit during the 1897–1898 Tirah Campaign. I guess that the Special Forces units are long standing, expertly trained groups of very special people, who have achieved a level of expertise that is second to none, and I for one, and thankful that such soldiers exist.

While visiting Alaska a few years ago, Bob and I kept hearing about Captain James Cook. I suppose I had probably heard a little about him at one point or another during my school years, but as often happens with kids, I wasn’t really interested…at least not until I saw Alaska for myself. Then, the places that were discussed in history actually came to life, because I was there in person. In reality, Captain Cook had a direct impact on several areas of the west coast of the United States, including the Puget Sound in Washington and areas of Oregon. Cook’s two ships, the Discovery and Resolution, had worked their way northwest from what is now Oregon and Puget Sound, along the British Columbia and Alaska coast, hoping to find the long sought after Northwest Passage to Europe.

While visiting Alaska a few years ago, Bob and I kept hearing about Captain James Cook. I suppose I had probably heard a little about him at one point or another during my school years, but as often happens with kids, I wasn’t really interested…at least not until I saw Alaska for myself. Then, the places that were discussed in history actually came to life, because I was there in person. In reality, Captain Cook had a direct impact on several areas of the west coast of the United States, including the Puget Sound in Washington and areas of Oregon. Cook’s two ships, the Discovery and Resolution, had worked their way northwest from what is now Oregon and Puget Sound, along the British Columbia and Alaska coast, hoping to find the long sought after Northwest Passage to Europe.

In early June 1778, Captain Cook and his men were in the Cook Inlet, hoping it would lead to the imagined passageway to Europe. It didn’t, of course, but once again Cook sent his crew exploring in small boats. Their adventures there led to the naming of Turnagain Arm, which Captain Cook originally called River Turnagain. It was so named because it was a disappointing “turn again” for Cook’s crew. The problem they were having was because Turnagain is subject to climate extremes and large tide ranges. During high tide, taking a boat in is simple, but if you don’t get out before low tide, you will find yourself fighting the quicksand-like mudflats that make up the beaches along Turnagain Arm in low tide.

In the times that Captain Cook was exploring for England, it was customary to name places after places and people in England. The visit to Cook Inlet was part of Cook’s longer exploration of the Alaska coast from which included a stop in Prince William Sound, which Cook named, along with Bligh Reef in the Sound. Bligh Reef would become famous in 1989 when the tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on it and spilled millions of gallons of crude oil. Prince William Sound, interestingly, was almost named “Sandwich Sound” by Cook after the Earl of  Sandwich in England, and who also, by the way, invented the sandwich as a food item. The Sound was renamed by Cook after Prince William, a descendent of the royal family when his journal was published. Leaving Prince William Sound, Cook ventured west along the Alaska coast to explore further, and after leaving Cook Inlet, he named Bristol Bay after Admiral Earl of Bristol, and Norton Sound after Sir Fletcher Norton, then Speaker of the British House of Commons. As he continued his quest for the Northwest Passage, Cook entered the Chukchi Sea through the Bering Strait and, amazingly, got as far as Icy Cape, on Alaska’s northwest coast, before being stopped by ice. In fact, the two ships were almost trapped by ice the off of Icy Cape.

Sandwich in England, and who also, by the way, invented the sandwich as a food item. The Sound was renamed by Cook after Prince William, a descendent of the royal family when his journal was published. Leaving Prince William Sound, Cook ventured west along the Alaska coast to explore further, and after leaving Cook Inlet, he named Bristol Bay after Admiral Earl of Bristol, and Norton Sound after Sir Fletcher Norton, then Speaker of the British House of Commons. As he continued his quest for the Northwest Passage, Cook entered the Chukchi Sea through the Bering Strait and, amazingly, got as far as Icy Cape, on Alaska’s northwest coast, before being stopped by ice. In fact, the two ships were almost trapped by ice the off of Icy Cape.

During his travels, Captain Cook named many other places, including Mount Edgecumbe and Cape Edgecumbe after George, Earl of Edgecumbe. He broke from protocol in naming Mount Fairweather and Cape Fairweather, using the fact that he had good weather at the time of his exploration, as inspiration for the names. Cross Sound was so named because he found it on May 3, designated on his calendar as Holy Cross day. Cape Suckling was named after Maurice Suckling, comptroller of the Royal Navy when Cook left England. Controller Bay was probably also named after Maurice Suckling, but the Russians translated the name to Zal Kontrolyer on the Hydrogaphy Department Chart 1378, dated 1847, and so it remained Controller Bay. Cape Hinchinbrook was named after Viscount Hinchinbroke. Snug Corner Cove was so named because Captain Cook thought, “And a very snug cove it is.” Montague Island was named after John Montagu, Earl of Sandwiche, the son of Viscount Hinchinbroke. The list of names and their origins goes on and on, but I find these the most interesting.

During his third visit to the Sandwiche Islands, which we now know as Hawaii, Captain James Cook lost his life  in a mob fight with the Hawaiian natives, who wanted one of his boats. As the men came ashore, the Hawaiians greeted Cook and his men by hurling rocks at them. They then stole a small cutter vessel from the Discovery. Negotiations with King Kalaniopuu for the return of the cutter collapsed after a lesser Hawaiian chief was shot to death, and a mob of Hawaiians descended on Cook’s party. The captain and his men fired on the angry Hawaiians, but they were outnumbered. Only a few managed to escape to the safety of the Resolution. Captain Cook was killed by the mob on February 14, 1779. A few days later, the Englishmen retaliated by firing their cannons and muskets at the shore, killing some 30 Hawaiians. The Resolution and Discovery eventually returned to England.

in a mob fight with the Hawaiian natives, who wanted one of his boats. As the men came ashore, the Hawaiians greeted Cook and his men by hurling rocks at them. They then stole a small cutter vessel from the Discovery. Negotiations with King Kalaniopuu for the return of the cutter collapsed after a lesser Hawaiian chief was shot to death, and a mob of Hawaiians descended on Cook’s party. The captain and his men fired on the angry Hawaiians, but they were outnumbered. Only a few managed to escape to the safety of the Resolution. Captain Cook was killed by the mob on February 14, 1779. A few days later, the Englishmen retaliated by firing their cannons and muskets at the shore, killing some 30 Hawaiians. The Resolution and Discovery eventually returned to England.

Every new invention has to have its trial run, but some of them might not be so easy to test as others. If you are testing a Frisbee to see if it flies, it is much different than testing a plane to see if it flies. Still, an invention cannot be used, sold, and especially patented without being tested, so testing must be done, and sometimes that can be a little bit dangerous.

Every new invention has to have its trial run, but some of them might not be so easy to test as others. If you are testing a Frisbee to see if it flies, it is much different than testing a plane to see if it flies. Still, an invention cannot be used, sold, and especially patented without being tested, so testing must be done, and sometimes that can be a little bit dangerous.

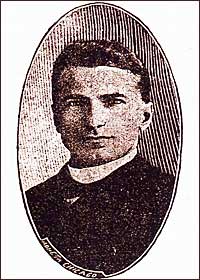

For many years, police work was extremely dangerous…even more so than it is now. Without some of the protective coverings the officers have today, they could be easily killed in the line of duty…not that they can’t now, but there is a little bit less chance of it these days. Kazimierz Zeglen, was a Polish engineer, born in 1869 near Ternopol. He is credited with inventing the first bulletproof vest. In 1893, after the assassination of Carter Harrison Sr, the mayor of Chicago, he invented the first commercial bulletproof vest. In 1897, he improved it together with Jan Szczepanik who was the inventor of the first commercial bulletproof armor in 1901. It saved the life of Alfonso XIII, the King of Spain…his carriage was covered with Szczepanik’s bulletproof armor when a bomb exploded near it.

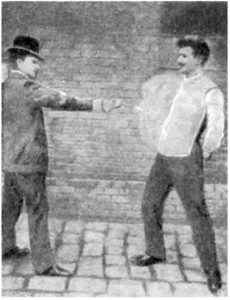

When the time came to test the bullet proof vest, a man names Mr Borzykowski, who was a friend of Szczepanik, agreed to test the vest…not on himself, mind you, but on his servant. When he shot his servant, it looks to me like the man braced for death, but he stood in place as he was told to do. It’s kind of like testing a shark suit for the first time. You would have no idea if you would see tomorrow or not. Once the vest was tested, however, it quickly became a valued piece of protective gear for police officers everywhere. The vest worked very well, but the early vests were quite heavy. Through the years, vests have much improved, and will continue to do so, as new materials become available.

When a new lighter vest was demonstrated by the Protective Garment Corporation of New York in 1923, it had to be proven again, because no one was willing to buy these vests sight unseen, so to speak. The gun players were WH Murphy and his assistant. Pictures were taken during a demonstration of the company’s bulletproof vest for DC area police. The live demonstration took place at the Washington city police headquarters. The inventors and salesmen were trying to convince the police force that these bulletproof vests did work and did save lives. The police officers in the background were all part of the Frederick County Police Department, the gun they were firing is believed to be a Smith and Wesson Model 10 Revolver. Mr

Murphy stood less than ten feet from the firing gun and took two consecutive .38 round slugs straight to the chest. An eye witnesses claims he “didn’t bat an eye” in both cases. Later Murphy gave the deflected .38 bullet to the police officer as a souvenir. This vest weighed 11 pounds, fit close to the body, and was considered more comfortable than the previous types of bulletproof vests. The bullet proof vest has become standard gear for police officers.

Murphy stood less than ten feet from the firing gun and took two consecutive .38 round slugs straight to the chest. An eye witnesses claims he “didn’t bat an eye” in both cases. Later Murphy gave the deflected .38 bullet to the police officer as a souvenir. This vest weighed 11 pounds, fit close to the body, and was considered more comfortable than the previous types of bulletproof vests. The bullet proof vest has become standard gear for police officers.

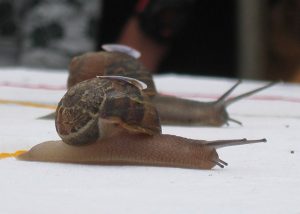

When I think of forms of entertainment, snail racing is about the furthest thing from my mind, but apparently it is a thing. In fact, on October 1, 1954 a ten year old boy named Martin Witter put his snail team through their rounds at a trial race at his home in Lynwood, California. Martin had formed, what he claimed to be, the only snail stable in the country. Every afternoon the snails were awakened for their trial runs by being placed in the sun. As the sunshine began to penetrate their shells, the snails came to life. On top of the racing snail’s shell, Martin had glued a tiny yoke made from a matchstick. The reins, made of string, were connected to a small simulated Roman chariot constructed from a fish food tin in which the snail driver sits. Speedy, in the harness and Butch, in the “Chariot” beat a neighborhood entry establishing a new track record of 3 feet in 5 minutes…not bad for a couple of racers, who we all know travel at a snail’s pace.

When I think of forms of entertainment, snail racing is about the furthest thing from my mind, but apparently it is a thing. In fact, on October 1, 1954 a ten year old boy named Martin Witter put his snail team through their rounds at a trial race at his home in Lynwood, California. Martin had formed, what he claimed to be, the only snail stable in the country. Every afternoon the snails were awakened for their trial runs by being placed in the sun. As the sunshine began to penetrate their shells, the snails came to life. On top of the racing snail’s shell, Martin had glued a tiny yoke made from a matchstick. The reins, made of string, were connected to a small simulated Roman chariot constructed from a fish food tin in which the snail driver sits. Speedy, in the harness and Butch, in the “Chariot” beat a neighborhood entry establishing a new track record of 3 feet in 5 minutes…not bad for a couple of racers, who we all know travel at a snail’s pace.

The “World Snail Racing Championships” is an annual event that started in Congham, Norfolk in the 1960s after  its founder Tom Elwes saw the same event in France. At the 1995 race the snails set the benchmark time of two minutes by a snail named Archie. The 2008 event had to be cancelled because the course was waterlogged by a period of heavy rain. That was also just days after the death of its founder, Tom Elwes. The 2008 World Championships was won by Heikki Kovalainen and a snail named after a Formula One racing driver, in a time of three minutes, two seconds. The 2010 World Championship was won by a snail called Sidney in a time of three minutes and 41 seconds.

its founder Tom Elwes saw the same event in France. At the 1995 race the snails set the benchmark time of two minutes by a snail named Archie. The 2008 event had to be cancelled because the course was waterlogged by a period of heavy rain. That was also just days after the death of its founder, Tom Elwes. The 2008 World Championships was won by Heikki Kovalainen and a snail named after a Formula One racing driver, in a time of three minutes, two seconds. The 2010 World Championship was won by a snail called Sidney in a time of three minutes and 41 seconds.

The first official live snail competitive race in London, the “Guinness Gastropod Championship” was held in 1999. It was called by horse racing commentator, John McCririck who started the race with the words “Ready, Steady, Slow”. This is the common terminology for the start of a race. The following year Guinness featured a snail race in their advertisement, Bet on Black as part of their “Good things come to those who wait” campaign. It kind of funny when you think about it. Waiting for the end of a snail race would definitely be a wait.  The advertisement won the silver award at the Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival and was self-parodied for their “Extra Cold” campaign several years later.

The advertisement won the silver award at the Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival and was self-parodied for their “Extra Cold” campaign several years later.

The “Grand Championship Snail Race” began in Cambridgeshire in 1992 in the village of Snailwell as part of its annual summer holiday. The event regularly attracts up to 400 people to the village, more than doubling its normal population. The rules are that you’re not allowed to touch your snail during the race, change snails or doing something that would make your snail go faster than it should. The snail has to win the race on its own.