History

Over the centuries, people have gone to great lengths to humiliate their enemies. The worst thing for the Jewish people was that over the centuries, there have been so many enemies. To this day, it doesn’t matter that Israel is one of the smallest nations in the world, the Muslim nations don’t even want them to have that small area, and the Muslims weren’t the only enemy of the Jewish people either. The Jews of Europe were legally forced to wear badges or distinguishing garments, like pointed hats, to let everyone know who they were. This practice began at least as far back as the 13th century. It continued throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but was then largely phased out during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the coming of the French Revolution and the emancipation of western European Jews throughout the 19th century, the wearing of Jewish badges was abolished in Western Europe.

Over the centuries, people have gone to great lengths to humiliate their enemies. The worst thing for the Jewish people was that over the centuries, there have been so many enemies. To this day, it doesn’t matter that Israel is one of the smallest nations in the world, the Muslim nations don’t even want them to have that small area, and the Muslims weren’t the only enemy of the Jewish people either. The Jews of Europe were legally forced to wear badges or distinguishing garments, like pointed hats, to let everyone know who they were. This practice began at least as far back as the 13th century. It continued throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but was then largely phased out during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the coming of the French Revolution and the emancipation of western European Jews throughout the 19th century, the wearing of Jewish badges was abolished in Western Europe.

Enter Hitler. The Nazis, under Hitler’s direction, resurrected this practice as part of humiliation tactics during the Holocaust. Reinhardt Heydrich, chief of the Reich Main Security Office, first recommended that Jews should wear identifying badges following the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9 and 10, 1938. Hitler liked the idea, because Hitler hated the Jews. Shortly after the invasion of Poland in September 1939, local German authorities began introducing mandatory wearing of badges. By the end of 1939, all Jews in the newly-acquired Polish territories were required to wear badges. Upon invading the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Germans again required the Jews in the newly-conquered lands to wear badges. Throughout the rest of 1941 and 1942, Germany, its satellite states and western occupied territories adopted regulations stipulating that Jews wear identifying badges. On May 29, 1942, on the advice of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler orders all Jews in occupied Paris to wear an identifying yellow star on the left side of their coats. Only in Denmark, where King Christian X is said to have threatened to wear the badge himself if it were imposed on his country’s Jewish population, were the Germans unable to impose such a regulation. Too bad some of the other nations did not stand up for the Jewish people too.

The Yellow Star was imposed on the Jewish people as part of many psychological tactics aimed at isolating and dehumanizing the Jews of Europe and especially by the Nazis. They were being directly marked as being different and inferior to everyone else. It also allowed the Germans to facilitate their separation from society and subsequent ghettoization, which ultimately led to the deportation and murder of 6 million Jews. Those who failed or refused to wear the badge risked severe punishment, including death. For example, the Jewish Council (Judenrat) of the ghetto in Bialystok, Poland announced that “… the authorities have warned that severe punishment – up to and including death by shooting – is in store for Jews who do not wear the yellow badge on back and front.” The star took on different forms in different regions, but everyone in the area knew what it

meant. Of course, the Jewish people hated the badge for what it symbolized, even though the Star of David had stood for the Jewish people since about the 12th century. While the Star of David, known as the Magen David, has continued to be the unofficial symbol of the Jewish people, even on their flag, the Menorah continues to be the official symbol of Judaism (The Jewish people). It seems to me that they would not really want the Star of David after all of the persecution that has been associated with it, but I guess it could be looked at as a badge of honor, as they, as a people survived the persecution.

meant. Of course, the Jewish people hated the badge for what it symbolized, even though the Star of David had stood for the Jewish people since about the 12th century. While the Star of David, known as the Magen David, has continued to be the unofficial symbol of the Jewish people, even on their flag, the Menorah continues to be the official symbol of Judaism (The Jewish people). It seems to me that they would not really want the Star of David after all of the persecution that has been associated with it, but I guess it could be looked at as a badge of honor, as they, as a people survived the persecution.

Memorial Day…an often misunderstood day, is actually a day to remember those military men and women who paid the ultimate price for our freedom…they gave their life in service to their country. Whether we know it or not, I’m sure that every family has lost a love one to war…some war in history. It might be many years in the past, and we may not even know about it at all, nevertheless, it is our duty to remember and to honor them, because they sacrificed their very lives that we might live in a free nation. It is so hard to think of someone that we care about, being killed in a foreign country while fighting a war.

Memorial Day…an often misunderstood day, is actually a day to remember those military men and women who paid the ultimate price for our freedom…they gave their life in service to their country. Whether we know it or not, I’m sure that every family has lost a love one to war…some war in history. It might be many years in the past, and we may not even know about it at all, nevertheless, it is our duty to remember and to honor them, because they sacrificed their very lives that we might live in a free nation. It is so hard to think of someone that we care about, being killed in a foreign country while fighting a war.

I am one of those people who doesn’t personally know of a family member lost in a war, but my Uncle Jim Richards brother, Dale was lost on the beaches of Normandy France on July 30, 1944. It is incomprehensible to me to think of his family getting word of his passing, only to find out that they would have to foot the bill to bring him home for burial. There simply were not enough funds, and so Dale was buried at the Brittany American Cemetery and Memorial, in Normandy, France. I can’t begin to imagine the awful day when the summer suddenly seemed as cold as ice. No parent should have to outlive their child, but with war comes death, and someone’s son or daughter will not be coming home again. I heard it put best in a song by Tim McGraw. The song, If you’re Reading This talks about getting a “one way ticket” over there. Unfortunately, far too many of our young men and women have been given that one way ticket, and while they paid with their lives, their families paid too. Their loved one is forever take from them, and they are left to mourn…to try to go on with their lives.

So many people look at Memorial Day as a holiday…a day to hold picnics, sports events and family gatherings. This day is traditionally seen as the start of the summer season for cultural events. For the fashion conscious, it is seen as acceptable to wear white clothing, particularly shoes from Memorial Day until Labor Day. However, fewer and fewer people follow this rule and many wear white clothing throughout the year. But how should we, the living, best honor the lives of all those who have died in service to our country? On Memorial Day, it is traditional to fly the flag of the United States at half staff from dawn until noon. Many people visit cemeteries  and memorials, particularly to honor those who have died in military service. Many volunteers place an American flag on each grave in national cemeteries. in reality, this is a day to reflect on the sacrifices made to keep us free. While we feel like we should be honoring veterans who have passed away, the reality is that their day is Veterans Day, which honors the veterans of all wars living or dead. Within the military, there is a very strict protocol concerning the days we honor military personnel. The other thing that we tend to find odd about Memorial Day, is that we can’t go to someone and thank them for their sacrifice, because the way they came to be honored is to have given their life for their country. All we can do is to honor their memory.

and memorials, particularly to honor those who have died in military service. Many volunteers place an American flag on each grave in national cemeteries. in reality, this is a day to reflect on the sacrifices made to keep us free. While we feel like we should be honoring veterans who have passed away, the reality is that their day is Veterans Day, which honors the veterans of all wars living or dead. Within the military, there is a very strict protocol concerning the days we honor military personnel. The other thing that we tend to find odd about Memorial Day, is that we can’t go to someone and thank them for their sacrifice, because the way they came to be honored is to have given their life for their country. All we can do is to honor their memory.

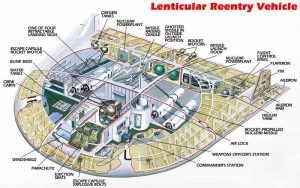

Many people have said they saw a flying saucer, and most have been laughed at, as the people they told about the flying saucer just couldn’t believe it was real. I’m not going to try to prove or disprove the flying saucer from outer space, but rather, I want to talk about the flying saucers of the United States Air Force. I can’t say if the flying saucers people have seen were actually the US Air Force’s Lenticular Reentry Vehicle, which was originally under research in the late 1950s. The Convair/Pomona division of General Dynamics initiated a project entitled Pye Wacket. The purpose of the project was to determine the feasibility of developing a missile-defense system based on flying discs…known as Lenticular vehicles. Although Pye Wacket was terminated by 1961, research had shown Lenticular-shaped vehicles possessed sound re-entry characteristics.

Many people have said they saw a flying saucer, and most have been laughed at, as the people they told about the flying saucer just couldn’t believe it was real. I’m not going to try to prove or disprove the flying saucer from outer space, but rather, I want to talk about the flying saucers of the United States Air Force. I can’t say if the flying saucers people have seen were actually the US Air Force’s Lenticular Reentry Vehicle, which was originally under research in the late 1950s. The Convair/Pomona division of General Dynamics initiated a project entitled Pye Wacket. The purpose of the project was to determine the feasibility of developing a missile-defense system based on flying discs…known as Lenticular vehicles. Although Pye Wacket was terminated by 1961, research had shown Lenticular-shaped vehicles possessed sound re-entry characteristics.

The project was classified as secret in 1962, but cleared for public information release December 28, 1999. It’s declassified technical report had been compiled by R J Oberto, Los Angeles Division of North American Aviation.  His report described the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle as an offensive weapons system. Popular Mechanics obtained information on the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle from a Freedom of Information Act request after documents describing the project were declassified in 1999. “The Lenticular Reentry Vehicle,” according to a November 2000 Popular Mechanics cover story, “was an experimental nuclear warhead delivery system under development during the Cold War by defense contractor North American Aviation, managed out of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.” According to Oberto’s report, “the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle was a 40 foot half-saucer with a flat rear edge. The design-study documents indicated it could support a crew of four men for six-week orbital missions. Propulsion was from a rocket engine…either chemical or nuclear, and the craft would also have contained an onboard nuclear reactor for electrical power generation.”

His report described the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle as an offensive weapons system. Popular Mechanics obtained information on the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle from a Freedom of Information Act request after documents describing the project were declassified in 1999. “The Lenticular Reentry Vehicle,” according to a November 2000 Popular Mechanics cover story, “was an experimental nuclear warhead delivery system under development during the Cold War by defense contractor North American Aviation, managed out of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.” According to Oberto’s report, “the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle was a 40 foot half-saucer with a flat rear edge. The design-study documents indicated it could support a crew of four men for six-week orbital missions. Propulsion was from a rocket engine…either chemical or nuclear, and the craft would also have contained an onboard nuclear reactor for electrical power generation.”

The existence of the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle program may bring credence to the idea of the military flying  saucers theory concerning unidentified flying objects, but the flight characteristics of the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle, as described by the documents released, are more similar to a standard orbital space capsule of the 1960s era, rather than the rapid motion and sudden velocity change characteristics of many reported UFOs. As of the publication of the Popular Mechanics article, there has been no official confirmation that the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle ever flew. Dynamic analysis of Lenticular missile configurations was conducted by the General Dynamics Pomona Division under Army Missile Command contract in the 1963. So, I guess the final decision goes to each person. Is it a UFO from outer space, or is it a Lenticular Reentry Vehicle (LRV) from the US Air Force?

saucers theory concerning unidentified flying objects, but the flight characteristics of the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle, as described by the documents released, are more similar to a standard orbital space capsule of the 1960s era, rather than the rapid motion and sudden velocity change characteristics of many reported UFOs. As of the publication of the Popular Mechanics article, there has been no official confirmation that the Lenticular Reentry Vehicle ever flew. Dynamic analysis of Lenticular missile configurations was conducted by the General Dynamics Pomona Division under Army Missile Command contract in the 1963. So, I guess the final decision goes to each person. Is it a UFO from outer space, or is it a Lenticular Reentry Vehicle (LRV) from the US Air Force?

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

The first contract was awarded in 1811, and included the first 10 miles of road. These days that seems like such a short distance, but in the early 1800s, I’m sure it was considered a big job. By 1818 the road was completed to Wheeling, West Virginia. It was at this point that mail coaches began using the road. By the 1830s the federal government turned over part of the road’s maintenance responsibility to the states through which it ran. In order to help pay for the road’s upkeep, tollgates and tollhouses were built by the states. As work on the road progressed a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages that were found along the National Road, remain barely touched by the passing of time. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning the nickname “The Main Street of America.” The height of the National Road’s popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry, but hard times hit in 1834, and construction on the road was tabled. During the 1840s popularity soared again. Travelers and drovers, westward bound, crowded the inns and taverns along the route. Huge Conestoga wagons hauled produce from farms on the frontier to the East Coast, and then returned with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands of people moved west in covered wagons and stagecoaches that traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In the 1870s, however, the railroads came and some of the excitement of the national road faded. In 1912 the road became part of the National Old Trails Road and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal Aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926 the road became part of US 40 as a coast-to-coast highway. As the interstate system has grown throughout America, interest in the National Road again waned. However, now when we want to have a relaxing journey with some history thrown in, we again travel the National Road. Cameras capture old buildings, bridges and old stone mile markers. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside and some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence and others stand abandoned.

Historic stone bridges dot their way along the National Road, and they have their own stories to tell. The craftsmanship of the early engineers was amazing. The S Bridge, was so named because of its design and it stands 4 miles east of Old Washington, Ohio. It was built in 1828 as part of the National Road. It is a single arch stone structure. This one of four in the state is deteriorated and is now used for only pedestrian traffic. However the owners of the bridge are attempting to obtain funding for its restoration. The stone Casselman River Bridge still stands east of Grantsville, Maryland. It is a product of the early 19th century federal government improvements program along the National Road, the Casselman River Bridge was constructed in 1813-1814. Its 80-foot span, is the largest of its type in America, and it connected Cumberland to the Ohio River. In 1933 a new steel bridge joined the banks of the Casselman River. The old stone bridge, partially restored by the State of Maryland in the 1950s is now the center of Casselman River Bridge State Park. Mile markers have been used in Europe for more than 2,000 years and our European ancestors continued that tradition here in America. These markers tell travelers how far they are from their destination and were an important icon in early National Road travel. Kids ask what they are fr, and adults nostalgically seek them out for photographing. A drive through National Road towns usually reveals one of these markers, such as the one standing by the historic Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio.

In the 1960s Interstate 70, bypassed Route 40 and much of the National Road, leaving many businesses by the wayside. People were looking for faster cars and quicker arrival times. Life runs at a much faster pace these

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

When we think of the outlaws of the old west, the term “gunfighter” or “gunslinger” were not the terms used to describe those men, or even the lawmen that some of them became upon changing their ways. They were actually originally called pistoleers, shootists, bad men, or one we do know…gunmen. That being said, Bat Masterson, who was a noted gunfighter himself, who later became a writer for the New York Morning Telegraph, sometimes referred to them as “gunfighters,” but, more often as “man killers.”

When we think of the outlaws of the old west, the term “gunfighter” or “gunslinger” were not the terms used to describe those men, or even the lawmen that some of them became upon changing their ways. They were actually originally called pistoleers, shootists, bad men, or one we do know…gunmen. That being said, Bat Masterson, who was a noted gunfighter himself, who later became a writer for the New York Morning Telegraph, sometimes referred to them as “gunfighters,” but, more often as “man killers.”

I suppose that Bat Masterson was probably the one who coined the term “gunfighter” in the first place, but many people from that era must have thought it an odd term to use. Still, if you heard an outlaw called a pistoleers, wouldn’t you have wondered what that was supposed to be? I would have, but then I would have looked it up and found that a pistoleers was “a soldier armed with a pistol.” That would have made no sense to me either, but in reality, some of the outlaws were soldiers who didn’t want to fight for a cause they didn’t believe in, so their deserted and headed west, so I guess they could have been pistoleers.

Another “movie mix-up” that happened is that in the old west, pistoleers or shootists didn’t squarely face off with each other from a distance in a dusty street, like they would like us to believe. In reality, the “real” gunfights of the Old West were rarely that “civilized.” Many fought in the many range wars and feuds of the Old West, which were far more common that the “stand-off” gunfight. Most of these were fought over land or water rights, some were political, and others were simply “old Hatfield-McCoy” style differences between families or in lifestyles. These people fought from the protection of anything available like a watering trough, a wall, building, or even a horse. Of those that more easily fit the perception of the “gunfighter,” you would find that they didn’t kill anywhere near the number of men they are credited with on television. In many instances their reputations stemmed from one particular fight, and the rumors grew from there, making people think they were that good. In other cases, self-promotion led people to believe they were lethal shootists, such was the case with Wyatt Earp and Wild Bill Hickok.

There were other, lesser known shootists, who actually saw just as much, if not more action than their well-known counterparts. Men like Ben Thompson, Tom Horn, Kid Curry, Timothy Courtright, King Fisher, Scott  Cooley, Clay Allison, and Dallas Stoudenmire, just to name a few, were often not credited for nearly the shooting ability of the well known shooters. Often these gunfighters, whose occupations ranged from lawmen, to cowboys, ranchers, gamblers, farmers, teamsters, bounty hunters, and outlaws, were violent men who could move quickly from fighting one side of the law to the other, depending on what suited them best at the time. Though many of these gunman died of “natural causes,” many died violently in gunfights, lynchings, or legal executions. The average age of death was about 35. However, of those gunman who used their skills on the side of the law, they would persistently live longer lives than those that lived a life of crime.

Cooley, Clay Allison, and Dallas Stoudenmire, just to name a few, were often not credited for nearly the shooting ability of the well known shooters. Often these gunfighters, whose occupations ranged from lawmen, to cowboys, ranchers, gamblers, farmers, teamsters, bounty hunters, and outlaws, were violent men who could move quickly from fighting one side of the law to the other, depending on what suited them best at the time. Though many of these gunman died of “natural causes,” many died violently in gunfights, lynchings, or legal executions. The average age of death was about 35. However, of those gunman who used their skills on the side of the law, they would persistently live longer lives than those that lived a life of crime.

These days, scientist and inventors have collaborated to develop early warning systems for just about any possible disaster, and when everything works as it should, and people heed the warnings, loss of life can often be avoided. Having the technology is great, but technology can’t make human beings do the right things…unfortunately. On May 22, 1960, twelve years after tsunami warnings were developed, and with the warning system in good working order, a massive 9.5 earthquake struck off the coast of Chili. It was the largest earthquake ever recorded. Unfortunately, we don’t really have an earthquake warning, and so without warning, 1655 people lost their lives in Chili and 3,000 injured in the quake. Two million people were made homeless, and damage was estimated at $550 million. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11pm. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly. Everyone assumed that the worst was over.

These days, scientist and inventors have collaborated to develop early warning systems for just about any possible disaster, and when everything works as it should, and people heed the warnings, loss of life can often be avoided. Having the technology is great, but technology can’t make human beings do the right things…unfortunately. On May 22, 1960, twelve years after tsunami warnings were developed, and with the warning system in good working order, a massive 9.5 earthquake struck off the coast of Chili. It was the largest earthquake ever recorded. Unfortunately, we don’t really have an earthquake warning, and so without warning, 1655 people lost their lives in Chili and 3,000 injured in the quake. Two million people were made homeless, and damage was estimated at $550 million. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11pm. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly. Everyone assumed that the worst was over.

Nevertheless, warnings were sent to the Hawaiian islands. The Pacific Tsunami Warning System properly and warnings were issued to Hawaiians six hours before the wave’s expected arrival. The response of some people, however, was reckless and irresponsible. Some people ignored the warnings, and others actually headed to the coast in order to view the wave. Arriving 15 hours after the quake, only a minute after predicted, the tsunami destroyed Hilo Bay, on the island of Hawaii. Thirty five foot waves bent parking meters to the ground and wiped away most buildings, destroying or damaging more than 500 homes and businesses. A 10 ton tractor was swept out to sea. Reports indicate that the 20 ton boulders making up the sea wall were moved 500 feet. Sixty-one people died in Hilo, the worst-hit area of the island chain. Damage was estimated at $75 million. This tsunami caused little damage elsewhere in the islands, where wave heights were in the 3-17 foot range. The tsunami continued to race further west across the Pacific. Ten thousand miles away from the earthquake’s epicenter. Japan, received warning, but wasn’t able to warn the people in harm’s way. At about 6pm, more than a day after the quake, the tsunami hit the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido. The  crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages. The Philippines, also hit, saw 32 people dead or missing.

crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages. The Philippines, also hit, saw 32 people dead or missing.

Tsunami warnings definitely save lives, but only if people will heed the warnings. As long as people decide that the warning doesn’t apply to them, and give in to their curiosity to go have a look, there will continue to be deaths. It seems a great shame that inventors and scientist work so hard to make a warning to save lives, and then some people refuse to do what is necessary to be safe after they have been warned. I simply don’t understand how people can ignore these warnings and take a chance with their lives.

As automobiles became commonplace…or at least more so than they had been, people began to realize that there needed to be some controls on their usage…specially in the area of speed. Most people know that is a car or other vehicle can go fast, there will always be someone out there, who wants to push the envelope and see just how fast it will go, throwing caution to the wind. With increased speeds would also follow, increased numbers of accidents. There would need to be some rules to follow.

As automobiles became commonplace…or at least more so than they had been, people began to realize that there needed to be some controls on their usage…specially in the area of speed. Most people know that is a car or other vehicle can go fast, there will always be someone out there, who wants to push the envelope and see just how fast it will go, throwing caution to the wind. With increased speeds would also follow, increased numbers of accidents. There would need to be some rules to follow.

There were already speed limits in the United States for non-motorized vehicles. In 1652, the colony of New Amsterdam, which is now New York, issued a decree stating that “[N]o wagons, carts or sleighs shall be run, rode or driven at a gallop” at the risk of incurring a fine starting at “two pounds Flemish,” or about $150 in today’s currency. In 1899, the New York City cabdriver Jacob German was arrested for driving his electric taxi at 12 miles per hour, but did the prior law really apply electric cars? It was becoming more and more obvious that some sort of legislation was necessary to ensure the safety of those operating these new machines, and those around them. So began the path to Connecticut’s 1901 speed limit legislation. Representative Robert Woodruff submitted a  bill to the State General Assembly proposing a motor-vehicles speed limit of 8 miles per hour within city limits and 12 miles per hour outside. While the law passed in May of 1901 specified higher speed limits, it required drivers to slow down upon approaching or passing horse-drawn vehicles, and come to a complete stop if necessary to avoid scaring the animals. I can’t imagine some of the restrictions listed there, because people would be stopped more than they were driving, but you have to start somewhere, and Connecticut was that starting point, when, on May 21, 1901 it became the first state to pass a law regulating motor vehicles, limiting their speed to 12 miles per hour in cities and 15 miles per hour on country roads.

bill to the State General Assembly proposing a motor-vehicles speed limit of 8 miles per hour within city limits and 12 miles per hour outside. While the law passed in May of 1901 specified higher speed limits, it required drivers to slow down upon approaching or passing horse-drawn vehicles, and come to a complete stop if necessary to avoid scaring the animals. I can’t imagine some of the restrictions listed there, because people would be stopped more than they were driving, but you have to start somewhere, and Connecticut was that starting point, when, on May 21, 1901 it became the first state to pass a law regulating motor vehicles, limiting their speed to 12 miles per hour in cities and 15 miles per hour on country roads.

Immediately following this landmark legislation, New York City went to work to keep up, and introduced the world’s first comprehensive traffic code in 1903. Adoption of speed regulations and other traffic codes was a slow and uneven process across the nation, however. As late as 1930, a dozen states had no speed limit, while 28 states did not even require a driver’s license to operate a motor vehicle. Rising fuel prices contributed to the lowering of speed limits in several states in the early 1970s, and in January 1974 President Richard Nixon  signed a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour into law. These measures led to a welcome reduction in the nation’s traffic fatality rate, which dropped from 4.28 per million miles of travel in 1972 to 3.33 in 1974 and a low of 2.73 in 1983.

signed a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour into law. These measures led to a welcome reduction in the nation’s traffic fatality rate, which dropped from 4.28 per million miles of travel in 1972 to 3.33 in 1974 and a low of 2.73 in 1983.

Concerns about fuel availability and cost later subsided, and in 1987 Congress allowed states to increase speed limits on rural interstates to 65 mph. The National Highway System Designation Act of 1995 repealed the maximum speed limit. This returned control of setting speed limits to the states, many of which soon raised the limits to 70 mph and higher on a portion of their roads, including rural and urban interstates and limited access roads.

With the eruption and possible explosion of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii, my thoughts are drawn back 38 years to another mountain…Mount Saint Helens. The scientists said that an explosive eruption was imminent. The mountain had been swelling up with internal pressure from the gasses deep in the earth. Still, some people didn’t believe the mountain would ever hurt them, and many just couldn’t wrap their head around the possibility that it might explode. So, some people stayed in their homes in the area. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

With the eruption and possible explosion of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii, my thoughts are drawn back 38 years to another mountain…Mount Saint Helens. The scientists said that an explosive eruption was imminent. The mountain had been swelling up with internal pressure from the gasses deep in the earth. Still, some people didn’t believe the mountain would ever hurt them, and many just couldn’t wrap their head around the possibility that it might explode. So, some people stayed in their homes in the area. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

It’s strange that we are able to associate things in life with major events in recent history. Many of us can say where we were when we learned of President Kennedy’s assassination, or when 9-11 took place. It is a moment that is embedded in our memories for all time. That morning as the ash rolled into our area, I was getting into my car to go to town. It looked like dust on my car, a very thick layer of dust. Of course, it wasn’t dust, it was volcanic  ash. It had never occurred to me that volcanic ash might affect me, but here I was, needing to wash the ash off of my car, so it was not damaged.

ash. It had never occurred to me that volcanic ash might affect me, but here I was, needing to wash the ash off of my car, so it was not damaged.

My cousin, Shirley, who lives in Washington, said she and her family were in Spokane. She saw a black cloud coming their way, and so she turned on the radio, to see what was going on. She immediately started yelling to the teachers and students from Saint Matthews school, who were at an end of the year baseball game. Every one scrambled to get their belongings, and headed back to the Church, before heading for home. Navigation became difficult. They had to watch the curb on the side of the streets to know where they were. It was a long drive home. They held their breath from the truck to the house, to protect their lungs, and watched the street lights come on. Shirley went out on the front porch and took pictures,  before retreating back to the safety of her house. They were forced to stay in the house for about a week, before it was safe to out again. Many safety precautions were in place, and people were told not to breathe the ash because of the glass in it.

before retreating back to the safety of her house. They were forced to stay in the house for about a week, before it was safe to out again. Many safety precautions were in place, and people were told not to breathe the ash because of the glass in it.

Mount Saint Helens is located in the Cascade Range. On May 18, 1980, at 8:32am Pacific Standard Time, it erupted and blasted 1,300 feet off of its top, sending hot mud, gas, and ash running down its slopes. Approximately 57 people were killed directly from the blast, while 200 houses, 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways, and 185 miles of highway were destroyed. Two people were killed indirectly in accidents that resulted from poor visibility, and two more suffered fatal heart attacks from shoveling ash. The explosion sent plumes of dark gray ash some 60,000 feet in the air which blocked out the rays from the sun making it seem like night over eastern Washington. So…where were you when Mount Saint Helens blew?

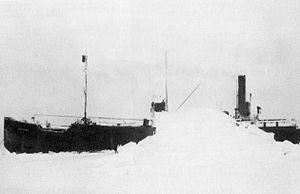

Ghost ships have been a prominent tale of mystery over the years. Many say that seeing a ghost ship is an omen of doom, which I do not believe in, nor do I believe in ghosts or ghost ships, but there was a ship that was dubbed a ghost ship, and has had the longest standing as a possible ghost ship in history, at least to my knowledge. The SS Baychimo was a cargo ship that was built in 1914 in Sweden. It was used for trading routes between Hamburg and Sweden. After World War I, the ship was sold to the Hudson’s Bay Company. The ship made numerous sailings for Hudson’s, mostly carrying cargo to and from the Arctic region.

Ghost ships have been a prominent tale of mystery over the years. Many say that seeing a ghost ship is an omen of doom, which I do not believe in, nor do I believe in ghosts or ghost ships, but there was a ship that was dubbed a ghost ship, and has had the longest standing as a possible ghost ship in history, at least to my knowledge. The SS Baychimo was a cargo ship that was built in 1914 in Sweden. It was used for trading routes between Hamburg and Sweden. After World War I, the ship was sold to the Hudson’s Bay Company. The ship made numerous sailings for Hudson’s, mostly carrying cargo to and from the Arctic region.

The Baychimo had a lucrative career until October 1, 1931, when it was on a routine voyage, filled with recently acquired furs. An unexpected storm blew in, trapping the ship in a sea filled with ice. The closest city was Barrow, Alaska, the northern most city in the United States, and almost like being on top of the world, but it was too far to get to in the blowing snow and high winds. The captain and crew had to stay inside the trapped ship, where they hoped to wait out the storm. This storm was the beginning of the more bizarre part of Baychimo’s life.

When October 15th rolled around, the ship could still be found stuck in the ice, so 15 of the crew members were airlifted to safety. The captain and 14 other crew members made a temporary camp on the ice near the stranded ship…which turned out to be a very wise decision. The terrible weather continued to pound the crew and the “temporary” camp became home for weeks. Then, on November 24th, a fierce blizzard hit the area, and the snow was so heavy that the campers could no longer see the Baychimo, which was still trapped in the ice…or so they thought. The next morning, it was just as the expected. The ship had vanished. They assumed that it had been sunk by the preceding blizzard. The remaining crew made their way back to civilization.

Then, less than a week later, a hunter told the captain that the Baychimo could not have sunk, as he had just seen it floating in the icy waters almost fifty miles from the location where it had been abandoned. The captain was, understandably reluctant to battle the snows to try and find the ship, knowing that it could be miles for the last known location. Nevertheless, he gathered his crew and went looking. Just as the hunter had said, they found the Baychimo in the location the hunter had described. The ship looked like it was no longer seaworthy, so the captain didn’t think it would stay afloat much longer and would soon break apart and sink, so the crew gathered the cargo of furs and had everything, including the captain and the crew, airlifted out of the area.

The captain was wrong. The SS Baychimo was spotted again and again. In March of 1933, some Eskimos, trapped by a storm, took shelter in the Baychimo for a week until the weather improved enough to journey back to their homes. In November of 1939, another ship came close enough to the Baychimo that they were  able to board the abandoned ship, but due to the approaching ice floes, the captain did not have the time to bring it back to a port, although he did report the empty ship’s location. In 1969, the Baychimo was spotted at a distance, once again trapped in an ice pack. This was the last recorded sighting of the ship, and after a few years it was commonly believed that the ship did eventually give in to its deteriorating condition and sank to the bottom of the frigid seas. Not everyone agreed though, because in 2006, seventy-five years after the ship was first abandoned, the state of Alaska formally began an effort to find the mysterious SS Baychimo, the Arctic’s elusive wandering ship.

able to board the abandoned ship, but due to the approaching ice floes, the captain did not have the time to bring it back to a port, although he did report the empty ship’s location. In 1969, the Baychimo was spotted at a distance, once again trapped in an ice pack. This was the last recorded sighting of the ship, and after a few years it was commonly believed that the ship did eventually give in to its deteriorating condition and sank to the bottom of the frigid seas. Not everyone agreed though, because in 2006, seventy-five years after the ship was first abandoned, the state of Alaska formally began an effort to find the mysterious SS Baychimo, the Arctic’s elusive wandering ship.

Since people began moving around the world there was a need for mail service, but people hated to wait months to hear from their loved ones…especially if it was with bad news. There had to be a way to get he mail faster and with the invention of the airplane, in late 1903, the possibility of a new way to deliver the mail was on the horizon. It really didn’t take very long for someone to make the metal leap from driving the mail to flying the mail from place to place. Where there is a need, there must be a solution. That solution came on May 15, 1918, when the United States officially established airmail service between New York and Washington DC, using Army aircraft and pilots. Prior to this date, the Post Office Department used new transportation systems such as railroads or steamboats to transport mail. They contracted with the owners of the lines to carry the mail. There were no commercial airlines to contract with, so no one had thought about that yet, but that was about to change.

Since people began moving around the world there was a need for mail service, but people hated to wait months to hear from their loved ones…especially if it was with bad news. There had to be a way to get he mail faster and with the invention of the airplane, in late 1903, the possibility of a new way to deliver the mail was on the horizon. It really didn’t take very long for someone to make the metal leap from driving the mail to flying the mail from place to place. Where there is a need, there must be a solution. That solution came on May 15, 1918, when the United States officially established airmail service between New York and Washington DC, using Army aircraft and pilots. Prior to this date, the Post Office Department used new transportation systems such as railroads or steamboats to transport mail. They contracted with the owners of the lines to carry the mail. There were no commercial airlines to contract with, so no one had thought about that yet, but that was about to change.

Army Major Reuben H. Fleet was charged with setting up the first US airmail service, scheduled to operate beginning May 15, 1918 between Washington DC, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New York City. The army pilots chosen to fly that day were Lieutenants Howard Culver, Torrey Webb, Walter Miller and Stephen Bonsal, all chosen by Major Fleet, and Lieutenants James Edgerton and George Boyle, both chosen by postal officials. Edgerton and Boyle had only recently graduated from the flight school at Ellington Field, Texas and neither had more than 60 hours of piloting time. While I’m sure they were a bit nervous, I’m also sure they were excited to be standing on the threshold of history.

The project got off to a bit of an embarrassingly rocky start, when Lieutenant Boyle, who was engaged to the daughter of Interstate Commerce Commissioner Charles McChord, was selected to pilot the first plane out of Washington DC that day. After all his preparations, Boyle hopped into his plane and was unable to start it. The plane had not been fueled. I’m sure that added a bit of nervousness to the situation. Nevertheless, he finally got his Curtiss Jenny, loaded with 124 pounds of airmail, into the air and made his way to Washington DC. His assignment was to fly to Philadelphia, the mid-way stop between the Washington and New York ends of the service. He did not make it there that day. The novice pilot got lost and low on gas, crash landed in rural Maryland, less than 25 miles away from Washington.

Fortunately for the service, the other flights operated as scheduled that day. Thanks to his political connections, Lieutenant Boyle was given a second chance to fly the airmail out of Washington DC. This time, he was given an escort who flew him out of the city, having given him directions to “follow the Chesapeake Bay” towards Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Boyle followed those instructions too literally, following the curve of the bay over to Maryland’s eastern shore, where he landed, out of fuel again. Not even Boyle’s connections could help him now, and he was removed from the pilots list for the service. I’m sure that didn’t help his standing with his future father-in-law either.

The other rookie pilot, Lieutenant James Edgerton, did much better on his flights and stayed with the service. Edgerton managed to keep his plane aloft during a violent storm that struck while he was on another flight, even as the propeller was pelted by hail. He stayed with the mail service until the next year, and became the Chief of Flying Operations. Then in August, the Post Office Department took over airmail operations with airplanes and civilian pilots of its own. Captain Benjamin Lipsner was named the first superintendent of the U.S. Airmail Service.

The first flight operated by the Post Office Department took off from College Park, Maryland, on August 12, 1918. The destination was New York. Max Miller flew that historic flight. Miller flew the new Curtiss R-4 aircraft. These new planes had more powerful Liberty 400 horsepower engines. Miller was the first pilot hired by the Post Office Department. He died when his plane caught fire and crashed on September 1, 1920. The Post Office Department decided to launch pathfinding flights from New York to Chicago in September 1918. A major obstacle was the Allegheny Mountains, considered by some to be the most dangerous territory on the route. U.S. Airmail Service Superintendent Benjamin Lipsner chose two of his best pilots, Eddie Gardner and Max Miller, for these flights. Eager competitors, Gardner and Miller turned the test into a race. On September 5,  1918, the pair left New York. Miller flew in a Standard airmail plane with a 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine. Gardner followed in a Curtiss R-4 with a 400-horsepower Liberty engine and was accompanied by Eddie Radel, a mechanic. As each pilot landed to refuel or make repairs, he eagerly called Lipsner in Chicago to find out where the other one was. A set of telegrams now in the National Postal Museum tracked their progress. Miller landed in Chicago first, at 6:55 p.m. on September 6. Gardner arrived the next morning, landing at 8:17 at Grant Park. Sometimes it isn’t about the size of the engine I guess. Of course, today, very few people use the postal service, not called “snail mail.” With the internet and texting we have almost instant access to our loved ones.

1918, the pair left New York. Miller flew in a Standard airmail plane with a 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine. Gardner followed in a Curtiss R-4 with a 400-horsepower Liberty engine and was accompanied by Eddie Radel, a mechanic. As each pilot landed to refuel or make repairs, he eagerly called Lipsner in Chicago to find out where the other one was. A set of telegrams now in the National Postal Museum tracked their progress. Miller landed in Chicago first, at 6:55 p.m. on September 6. Gardner arrived the next morning, landing at 8:17 at Grant Park. Sometimes it isn’t about the size of the engine I guess. Of course, today, very few people use the postal service, not called “snail mail.” With the internet and texting we have almost instant access to our loved ones.