History

Saint Patrick’s Day…a day to celebrate being Irish. For me, Saint Patrick’s Day always felt like a borrowed holiday…probably because I don’t live in Ireland. The reality is that while I don’t live in Ireland, I am part Irish…9% to be exact. With the Irish in my family history, I would have expected my percentage to be for that 9%, but the reality is that most families migrated around the world, and while a family might have been in a country for centuries, they may not have originated there. Nevertheless, I had and still have family who live in Ireland, so I guess that makes me enough Irish to make Saint Patrick’s Day as much my day as it is anyone else’s. In reality, it is a day to remember the patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick was a missionary who heralded the shift from paganism to Christianity in the fifth century, when he was in his 40s. Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated on what is believed to be the anniversary of his death…March 17.

Saint Patrick’s Day…a day to celebrate being Irish. For me, Saint Patrick’s Day always felt like a borrowed holiday…probably because I don’t live in Ireland. The reality is that while I don’t live in Ireland, I am part Irish…9% to be exact. With the Irish in my family history, I would have expected my percentage to be for that 9%, but the reality is that most families migrated around the world, and while a family might have been in a country for centuries, they may not have originated there. Nevertheless, I had and still have family who live in Ireland, so I guess that makes me enough Irish to make Saint Patrick’s Day as much my day as it is anyone else’s. In reality, it is a day to remember the patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick was a missionary who heralded the shift from paganism to Christianity in the fifth century, when he was in his 40s. Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated on what is believed to be the anniversary of his death…March 17.

It is traditional to wear green on Saint Patrick’s Day, but why is that? Legend has it that if you’re wearing the color green, the quintessentially Irish, fairy-like creatures called leprechauns won’t be able to see you. And if they can’t see you, they can’t pinch you. Interestingly, before Saint Patrick’s Day got started, leprechauns were known not for wearing green but red. These days, the leprechauns have begun to outsource pinching to the rest of the world, or maybe we just took it over. Even the Irish flag has green in it. It is deeply symbolic. The green represents the Irish Catholics, the orange represents the Protestants and the white represents peace between the two. The green itself is called “shamrock green.” And speaking of shamrocks, shamrocks are one of the national symbols of Ireland, and not without reason. St. Patrick himself used the green, three-leaf clover to teach the Irish about the Holy Trinity: one for the father; one for the son; and one for the Holy Spirit. The four-leaf clover is just a symbol of good luck, if you believe in luck. Personally, I prefer blessing over luck.

When a large population of the Irish came to the United States in the mid-1800s, they wore the color green (as well as the Irish flag) as a point of national pride, further solidifying the relationship between the color green and the Irish…in the American imagination anyway. But lets face it, it’s really about the kid in all of us. Celebrating Saint Patrick’s Day with pinches and shamrock accessories might seem silly, but it can be a great way to spend a day being a little bit on the goofy side. Friendly pinches of those who are forgetful, and show up with no green, is a great way to spend that one day…often still cold and even snowy, having a little bit of silly fun. And then there is the green beer, the green Chicago river, and the green clothing, hair, and beards of our friends.

When a large population of the Irish came to the United States in the mid-1800s, they wore the color green (as well as the Irish flag) as a point of national pride, further solidifying the relationship between the color green and the Irish…in the American imagination anyway. But lets face it, it’s really about the kid in all of us. Celebrating Saint Patrick’s Day with pinches and shamrock accessories might seem silly, but it can be a great way to spend a day being a little bit on the goofy side. Friendly pinches of those who are forgetful, and show up with no green, is a great way to spend that one day…often still cold and even snowy, having a little bit of silly fun. And then there is the green beer, the green Chicago river, and the green clothing, hair, and beards of our friends.

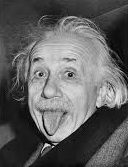

When I think of a genius, my favorite genius always comes to mind…Albert Einstein. He doesn’t have the highest recorded IQ in history, and in fact, is listed as 12th among geniuses. Nevertheless, Genius Day…a day to highlight the greatest minds out there, falls on Albert Einstein’s birthday, so maybe he is a favorite of a lot of people. It makes sense, because Albert Einstein is on of the most famous, iconic, influential, and admired people in history. He was incredibly smart, but oddly not snobby about it, like some geniuses, who rub me the wrong way.

When I think of a genius, my favorite genius always comes to mind…Albert Einstein. He doesn’t have the highest recorded IQ in history, and in fact, is listed as 12th among geniuses. Nevertheless, Genius Day…a day to highlight the greatest minds out there, falls on Albert Einstein’s birthday, so maybe he is a favorite of a lot of people. It makes sense, because Albert Einstein is on of the most famous, iconic, influential, and admired people in history. He was incredibly smart, but oddly not snobby about it, like some geniuses, who rub me the wrong way.

I wonder what it must have been like to be a genius in a day when the system didn’t necessarily recognize such things. Einstein started school, as most children did, in a normal Catholic elementary school, in Munich, Germany, and remained there for 3 years. At that point, they realized that they didn’t have the ability to teach such a child. He was transferred to he Luitpold Gymnasium (now known as the Albert Einstein Gymnasium) at age 8, where he received advanced primary and secondary school education until he left the German Empire seven years later. In German, gymnasium means high school. Einstein excelled at math and physics right from the start. He reached a mathematical level years ahead of his peers. At twelve years old, Einstein taught himself algebra and Euclidean geometry in one summer. Einstein also independently discovered his own original proof of the Pythagorean theorem at age 12. Those were years of intense discovery for him…discoveries that most people could never begin to fathom. At age 13, Einstein was introduced to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and Kant became his favorite philosopher, his tutor stating: “At the time he was still a child, only thirteen years old, yet Kant’s works, incomprehensible to ordinary mortals, seemed to be clear to him.” Probably his best known work was the Theory of Relativity, which actually took in two theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity. Concepts introduced by the theories of relativity include spacetime as a unified entity of space and time, relativity of simultaneity, kinematic and gravitational time dilation, and length contraction. If you don’t understand all of that, you are in good company.

It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to attempt to teach such a great mind anything. Seriously,

what could an average teacher teach him that he couldn’t learn on his own, and even begin to teach the teacher. I suppose that is the case with any genius, and it must have been a problem for many a teacher, not to mention to the child’s parents. Geniuses are a phenomena that most of us can only imagine, and maybe that is why it is felt that they should have a national day of their own. Often, the day is celebrated by a gathering of confirmed geniuses getting together to “show off” their skills. It is filled with competitions designed to exercise their minds in a group of their peers, which is definitely something they don’t get to do very often. I can’t think of a more fitting day for it to be celebrated than Albert Einstein’s birthday.

what could an average teacher teach him that he couldn’t learn on his own, and even begin to teach the teacher. I suppose that is the case with any genius, and it must have been a problem for many a teacher, not to mention to the child’s parents. Geniuses are a phenomena that most of us can only imagine, and maybe that is why it is felt that they should have a national day of their own. Often, the day is celebrated by a gathering of confirmed geniuses getting together to “show off” their skills. It is filled with competitions designed to exercise their minds in a group of their peers, which is definitely something they don’t get to do very often. I can’t think of a more fitting day for it to be celebrated than Albert Einstein’s birthday.

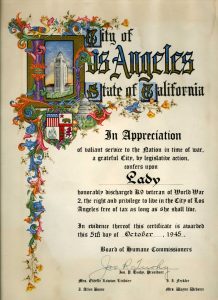

Most of us think of dogs as pets, and so they are, but they are so much more. Dogs know when their master is sick, lonely, or worried. Dogs ask little of their masters, and give so much back, but there is a group of dogs who are working dogs. In fact, we often see dogs in everyday life and think little of their presence, when in fact, their work is vital to those they work for. One of the most well known working dog groups is the K-9 Units. We think of these dogs as police dogs, and so they are, but originally, the K-9 Corps were founded in World War II. Of course, dogs were used long before that war, but not in the capacity of World War II.

Most of us think of dogs as pets, and so they are, but they are so much more. Dogs know when their master is sick, lonely, or worried. Dogs ask little of their masters, and give so much back, but there is a group of dogs who are working dogs. In fact, we often see dogs in everyday life and think little of their presence, when in fact, their work is vital to those they work for. One of the most well known working dog groups is the K-9 Units. We think of these dogs as police dogs, and so they are, but originally, the K-9 Corps were founded in World War II. Of course, dogs were used long before that war, but not in the capacity of World War II.

The Romans used dogs in battles, sending them in to attack the enemy. Native Americans used them as pack animals, as well as sentry animals. Even in the Middle Ages, dogs were sent into battle equipped with their own armor. Modern European societies had long established traditions of using dogs in war. But, I think that their use was probably made most famous 77 years ago, when in January of 1942, Dogs for Defense, Inc. was established as a national organization to help procure dogs for war training purposes. Although some dogs were acquired through purchase, it was largely through the dog owner population’s patriotic sentiments that most dogs were acquired for training. That really amazes me. I understand patriotism, and how people would volunteer in the service, but it seems strange to me to volunteer your dog.  Nevertheless, they did. It was the job of Dogs For Defense not only to procure the dogs, but also to train them. Once trained, the dogs were to be given to the Quartermaster General, who then turned them over to the Plant Protection Branch and Inspection Division. Many thought the primary use of dogs would be as sentries for civilian war plants and quartermaster depot, but dogs have proven to be a much more.

Nevertheless, they did. It was the job of Dogs For Defense not only to procure the dogs, but also to train them. Once trained, the dogs were to be given to the Quartermaster General, who then turned them over to the Plant Protection Branch and Inspection Division. Many thought the primary use of dogs would be as sentries for civilian war plants and quartermaster depot, but dogs have proven to be a much more.

There are dogs that can sniff out drugs, gun powder…and the enemy. The DFD trained over 10,000 dogs. Most of the dogs were used at home for sentry duty, however, more than 1,800 dogs were sent into combat starting in 1942. The US Marine Corps sent over 1,000 dogs to be trained at their Camp Lejeune facility. Unfortunately, many commanders were unfamiliar, and maybe a little distrusting of the dogs, and didn’t know how to use them to their advantage. Seven Quartermaster Corps War Dog Platoons were sent to the European Theatre of Operations, but they did not have much success, probably due mostly to the lack of training with their handlers. In 1943, the QMC sent a detachment of six scout dogs and two messenger dogs to operate in the  Pacific Theatre. This was a test of their value in combat conditions. The Japanese troops had deeply entrenched themselves on many islands in the Pacific theater of operations. Thousands were hiding in caves and in the dense jungles. They would lie very still, in wait for patrolling Marines and soldiers and then ambush them before the troops ever detected enemy forces. This is where the dogs proved their value. The first war dog platoons took to the Pacific island of New Britain. Here Marine war dogs attached to the Sixth Army first worked on sentry duty. Once a beachhead was established the dogs and handlers began conducting their patrols. They went on forty-eight patrols in fifty-three days. The dog patrols captured or killed 200 Japanese soldiers. This early success of war dog platoons set the standard for what could be expected, and what could not, from a K-9 detachment. I think that the more training given to both dogs and handlers, the better the results will be, as we have seen in K-9 police dogs in modern times.

Pacific Theatre. This was a test of their value in combat conditions. The Japanese troops had deeply entrenched themselves on many islands in the Pacific theater of operations. Thousands were hiding in caves and in the dense jungles. They would lie very still, in wait for patrolling Marines and soldiers and then ambush them before the troops ever detected enemy forces. This is where the dogs proved their value. The first war dog platoons took to the Pacific island of New Britain. Here Marine war dogs attached to the Sixth Army first worked on sentry duty. Once a beachhead was established the dogs and handlers began conducting their patrols. They went on forty-eight patrols in fifty-three days. The dog patrols captured or killed 200 Japanese soldiers. This early success of war dog platoons set the standard for what could be expected, and what could not, from a K-9 detachment. I think that the more training given to both dogs and handlers, the better the results will be, as we have seen in K-9 police dogs in modern times.

I think that anyone who has studied the Civil War, knows that it got started when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861…officially anyway. Of course, the Civil War was all about slavery, and the North and South could not agree on the issue. As with all wars, there was some posturing before the war actually got started. Each side tries to scare the other into compliance, but sometimes that just doesn’t work out. The strange thing about the Civil War was that the “posturing stage” of the war ended up being a comedy of errors, when an inexperienced gunner accidently discharged his cannon into the fort on March 12, 1861. After the error, in which no one was hurt or killed, thankfully, the Confederates had to row over and apologize for the mistake. That strikes me as really funny, because everyone knew the war was coming, but just not when it would start.

I think that anyone who has studied the Civil War, knows that it got started when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861…officially anyway. Of course, the Civil War was all about slavery, and the North and South could not agree on the issue. As with all wars, there was some posturing before the war actually got started. Each side tries to scare the other into compliance, but sometimes that just doesn’t work out. The strange thing about the Civil War was that the “posturing stage” of the war ended up being a comedy of errors, when an inexperienced gunner accidently discharged his cannon into the fort on March 12, 1861. After the error, in which no one was hurt or killed, thankfully, the Confederates had to row over and apologize for the mistake. That strikes me as really funny, because everyone knew the war was coming, but just not when it would start.

All that “practice” apparently didn’t help either, because when the war actually started, they fired over 3,000  shells at the fort without injuring a single Union soldier. Nevertheless, the men at the fort were apparently intimidated, because they surrendered and a Confederate officer named Roger Pryor rowed out to negotiate the terms. As the discussion progressed, Pryor casually got up, poured himself a glass of whiskey. Probably not the best idea. He downed it in one gulp, before finding out that it was actually a bottle of medical iodine that happened to be nearby. Pryor’s “Three Stooges” moment ended with army doctors frantically pumping his stomach while nervous Union officers wondered how they were going to explain poisoning the negotiator. I can see it all now. The Union doctors were scrambling to save Pryor’s life, all the while thinking that the Confederate soldiers were going to accuse them of trying to murder him. Fortunately, Pryor survived, but the comedy of errors did not end there. In what would become one last screw-up, and to mark the surrender, the Union commander ordered his gunners to fire a salute. Once again, the “training” given was lacking or the soldiers were just careless. The gunners piled cartridges next to

shells at the fort without injuring a single Union soldier. Nevertheless, the men at the fort were apparently intimidated, because they surrendered and a Confederate officer named Roger Pryor rowed out to negotiate the terms. As the discussion progressed, Pryor casually got up, poured himself a glass of whiskey. Probably not the best idea. He downed it in one gulp, before finding out that it was actually a bottle of medical iodine that happened to be nearby. Pryor’s “Three Stooges” moment ended with army doctors frantically pumping his stomach while nervous Union officers wondered how they were going to explain poisoning the negotiator. I can see it all now. The Union doctors were scrambling to save Pryor’s life, all the while thinking that the Confederate soldiers were going to accuse them of trying to murder him. Fortunately, Pryor survived, but the comedy of errors did not end there. In what would become one last screw-up, and to mark the surrender, the Union commander ordered his gunners to fire a salute. Once again, the “training” given was lacking or the soldiers were just careless. The gunners piled cartridges next to  their cannons…in a high wind. The resulting explosion killed two of their own men, the only casualties of the siege.

their cannons…in a high wind. The resulting explosion killed two of their own men, the only casualties of the siege.

The war had at least one other comedy of errors, this time in Congress. In 1858, tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions were so heated that a huge brawl broke out between at least 30 Congressmen on the House floor. This was not just an argument, it was a brawl, and it only came to an end when Mississippi’s William Barksdale had his wig knocked off. Since Barksdale never admitted to wearing a wig, he quickly snatched it back up and put it on inside out, causing everyone to stop fighting and start laughing instead. Barksdale didn’t think it funny, but I do.

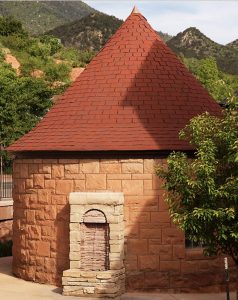

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

As the story goes, “centuries ago a Shoshone and a Comanche stopped at Manitou Springs on their return from a hunt to get a drink of water. The Shoshone had been successful, but the Comanche was empty-handed and ill-tempered, jealous of the other’s skill and fortune. Flinging down the fat deer that he was bearing homeward on his shoulders, the Shoshone bent over the spring of sweet water, and, after pouring a handful of it on the ground, as a libation (an act of pouring a liquid as a sacrifice) to the spirit of the place, he put his lips to the surface.”

The Comanche saw an opportunity to vent his anger. His quarrel began like this, “Why does a stranger drink

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

It is said, that the Shoshone didn’t answer, but as Ausaqua stooped toward the bubbling surface Wacomish crept behind him. He jumped on him and pushed his head under the water, holding it there until he drowned. It is said that as Wacomish “pulled the dead body from the spring the water became agitated, and from the bubbles arose a vapor that gradually assumed the form of a venerable Indian, with long white locks, in whom the murderer recognized Waukauga, father of the Shoshone and Comanche nation, and a man whose heroism and goodness made his name revered in both these tribes.” The face of the patriarch was dark with wrath, and he cried, in terrible tones, “Accursed of my race! This day thou hast severed the mightiest nation in the world. The blood of the brave Shoshone appeals for vengeance. May the water of thy tribe be rank and bitter in their throats.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

Of course, all this is folk lore, but the springs are real. They are Iron Spring, Twin Spring, Stratton Spring, Shoshone Spring, Wheeler Spring, Cheyenne, Soda and Navajo Springs, and Seven Minute Spring.

Governments don’t like to lose things…especially nuclear weapons. In fact, several movies have made that have depicted just how it might be done, and what the consequences might be if the thieves were successful. Of course, nothing could be more strange than to have it actually happen. In reality, it did happen…on March 10, 1956. It was on of the strangest mysteries in the United States. The B47 Stratojet took off from MacDill Air Force Base in Florida, on a non-stop flight bound for Ben Guerir Air Base, Morocco. The plane had completed the first aerial refueling without incident.

Governments don’t like to lose things…especially nuclear weapons. In fact, several movies have made that have depicted just how it might be done, and what the consequences might be if the thieves were successful. Of course, nothing could be more strange than to have it actually happen. In reality, it did happen…on March 10, 1956. It was on of the strangest mysteries in the United States. The B47 Stratojet took off from MacDill Air Force Base in Florida, on a non-stop flight bound for Ben Guerir Air Base, Morocco. The plane had completed the first aerial refueling without incident.

As the plane was beginning it’s second refueling attempt, it was  descending into a cloud. In one of the strangest mysteries in United States government history, contact was lost with the plane in the cloud. No debris, crew, or missiles were ever located. After descending through solid cloud to begin the second refueling, at 14,000 feet, B-47E serial number 52-534, failed to make contact with its tanker. The unarmed aircraft was carrying two capsules of nuclear weapons material in carrying cases. Losing a bomber carrying nuclear weapons, could be catastrophic, but the nukes were never a threat to start a nuclear war. There are plenty of safety precautions to avoid such issues when a plane is going down. Also notable is the fact that in 1956, there were no hackers who could take over a weapon from the inside. The United States government has lost a total of 11 nukes, and two of them still remain the biggest mystery are from this flight.

descending into a cloud. In one of the strangest mysteries in United States government history, contact was lost with the plane in the cloud. No debris, crew, or missiles were ever located. After descending through solid cloud to begin the second refueling, at 14,000 feet, B-47E serial number 52-534, failed to make contact with its tanker. The unarmed aircraft was carrying two capsules of nuclear weapons material in carrying cases. Losing a bomber carrying nuclear weapons, could be catastrophic, but the nukes were never a threat to start a nuclear war. There are plenty of safety precautions to avoid such issues when a plane is going down. Also notable is the fact that in 1956, there were no hackers who could take over a weapon from the inside. The United States government has lost a total of 11 nukes, and two of them still remain the biggest mystery are from this flight.

Despite an extensive search, no debris were ever found, and the crash site has never been located. The crew, who has been declared dead are Captain Robert H. Hodgin, 31, the aircraft commander; Captain Gordon M. Insley, 32, observer; 2nd It. Ronald L. Kurtz, 22, pilot. The plane’s last known position was over or near the Mediterranean Sea, southeast of Port Say, an Algerian coastal village near the Moroccan frontier. A French news agency reported that the plane may have exploded in flight near Sebatna in eastern French Morocco, but that seems unlikely, since no debris was ever found. It certainly makes you wonder what happened.

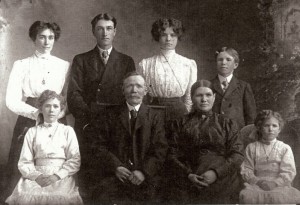

Most national days that are designed to celebrate an activity or group, are just another day to most of us, but for me, and for many other family history buffs, Genealogy Day is different. I’m sure everybody has a day of celebration that hits home to them, but I know of so many people who are dedicated to tracing their family history. I’m sure everyone has different reasons for tracing their history…from adoptees finding their parents, to simply wanting to know which historical figures we are related to, many people are curious. Those of us who have begun this journey, find ourselves losing track of time as were research the proof of relationship between us and our ancestors. We get started, and the addiction sets in. It’s like a good book that we simply can’t put down.

Most national days that are designed to celebrate an activity or group, are just another day to most of us, but for me, and for many other family history buffs, Genealogy Day is different. I’m sure everybody has a day of celebration that hits home to them, but I know of so many people who are dedicated to tracing their family history. I’m sure everyone has different reasons for tracing their history…from adoptees finding their parents, to simply wanting to know which historical figures we are related to, many people are curious. Those of us who have begun this journey, find ourselves losing track of time as were research the proof of relationship between us and our ancestors. We get started, and the addiction sets in. It’s like a good book that we simply can’t put down.

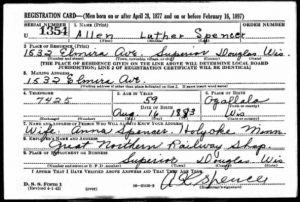

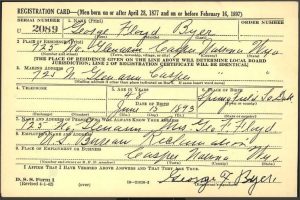

All too often, by the time we think about researching our ancestors, any of our family members who might have any pertinent information are already gone. We find ourselves disgusted that we weren’t interested before that point. Of course, by then it is too late for us, unless someone else took the time to ask the questions, and record the information. That is where the family genealogists come into play. If you are blessed, you have a parent or grandparent that you can ask or who has written it all down for you, so you don’t end up in the sad situation of finding that you are hitting a wall in your research. Those of us who find ourselves in the self-appointed position of being the family historian or family genealogist are not sorry that this is what we do. It is exciting to come across an old picture that we never thought we would find, or a military draft registration card that contains the signature of our ancestor. Those things are like striking it rich in a gold mine.

People are busy, and we just don’t have a lot of time to dig through the past, but every now and then, people who happen to have a bit more time start digging around and sometimes find out the most fascinating facts about where their forefathers came from and what kind of people they were. Most people are a little bit curious, when someone brings the information to their attention, but some simply don’t think they care. I find the latter group to be the most sad. They simply don’t understand that they are missing out…until it’s too late.

People are busy, and we just don’t have a lot of time to dig through the past, but every now and then, people who happen to have a bit more time start digging around and sometimes find out the most fascinating facts about where their forefathers came from and what kind of people they were. Most people are a little bit curious, when someone brings the information to their attention, but some simply don’t think they care. I find the latter group to be the most sad. They simply don’t understand that they are missing out…until it’s too late.

Keeping track of one’s family lines has been going on for centuries…hence the wealth of information that is out there, but never has the information been easier to access that it is today. Computers, cell phone apps, digital pictures all make it easier to share what one has with another, without losing the treasure you have. In Western societies, genealogy was especially important to royalty, who used it to decide who was of noble descent and who was not, as well as who had the right to rule which geographical area, but I think everyone wants to kind a link to a royal line. The idea that our grandparents might be royalty is an exciting one…even if our royal family will never know who we are.

Genealogy Day was created in 2013, by Christ Church, United Presbyterian and Methodist in Limerick, Ireland to help celebrate the church’s 200th anniversary. For this day, Christ Church brought together local family history records not only from its own combined churches, but also from the area’s Church of Ireland parishes, including the Religious Society if Friends in Ireland (Quaker) and the Church of Latter Day Saints (Mormon). The people in attendance could then use the amassed marriage and baptism records dating back to the early

1800s, such as Limerick Methodist Registers and Limerick Presbyterian Registers, to find out about their great-great-grandparents. The idea was so popular that it was repeated for the next two consecutive years and has inspired many people to take a look into their family tree to find out a bit more about where they come from. I think that Genealogy Day is a perfect day to dip your toe in the Genealogical waters, and see what you can find out about your own family. You might be surprised.

1800s, such as Limerick Methodist Registers and Limerick Presbyterian Registers, to find out about their great-great-grandparents. The idea was so popular that it was repeated for the next two consecutive years and has inspired many people to take a look into their family tree to find out a bit more about where they come from. I think that Genealogy Day is a perfect day to dip your toe in the Genealogical waters, and see what you can find out about your own family. You might be surprised.

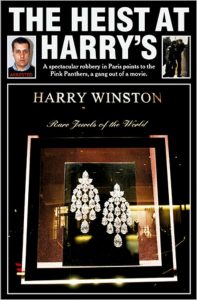

Jewelry heists usually come in the form of someone robbing a jewelry store, and they are usually caught pretty quickly due to all the security cameras these days. But, when a jewelry heist nets 85 million euros ($95,058,560 in US dollars) the thieves have to do a little more planning…if they plan to remain anonymous and get away with their heist, that is. In reality, there were two heists that took place at Harry Winston’s Avenue Montaigne shop, and the grand total was $113 million in jewelry and other valuables. The heists took place in October of 2007 and December of 2008.

Jewelry heists usually come in the form of someone robbing a jewelry store, and they are usually caught pretty quickly due to all the security cameras these days. But, when a jewelry heist nets 85 million euros ($95,058,560 in US dollars) the thieves have to do a little more planning…if they plan to remain anonymous and get away with their heist, that is. In reality, there were two heists that took place at Harry Winston’s Avenue Montaigne shop, and the grand total was $113 million in jewelry and other valuables. The heists took place in October of 2007 and December of 2008.

These robbers were very sophisticated in how they carried out these heists. The heists were carried out in broad daylight. In the 2008 robbery, the men boldly walked in through the front door of Harry Winston’s Paris shop. Despite the fact that three of them were dressed as women in wigs and heels, they were all men. They walked in, pulled a hand grenade and a gun, and in less than 20 minutes, the security guard held the door for them as they walked out to a waiting car with their rolling suitcase filled with over $90 million of jewels and watches.

Eight men were convicted for their roles in those two bold jewelry heists in 2007 and 2008, in which they made off with an estimated $113 million in jewelry and other valuables, most of which has never been found. It was said that the police never had a chance. That was in December of 2008 and to the frustration of Harry Winston, their insurer Lloyds of London, and the police, it was the second massive jewelry heist at the store in just over a year. The earlier job took place in October in 2007 and involved four men masquerading as builders. They  were let in through a back door with the help of an inside man and made off with close to $30 million in diamonds, luxury watches, necklaces, earrings and other valuables

were let in through a back door with the help of an inside man and made off with close to $30 million in diamonds, luxury watches, necklaces, earrings and other valuables

Finally, in March 2011, there was a small breakthrough when the police recovered some of the jewelry after a 2009 crime sweep in Paris. Police recovered $20 million worth of jewelry (19 rings and three sets of earrings) from the 2008 heist. Found in a drain in the Parisian suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis, it was all that was ever located.

After a trial that started in early February, eight men were convicted for their roles in the crimes. Their sentences ranged from nine months to 15 years. The longest sentence was for the crime’s purported mastermind, Douadi Yahiaoui, a repeat criminal offender and drug trafficker. His 59 year old brother Mohammed was also convicted. In all, the Paris police arrested 25 men in the Harry Winston jewel heist probe. The suspects ranged from 22 years old to 67 years old.

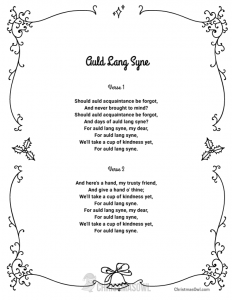

I think we have all been to a New Year’s Eve party, and at the stroke of midnight, everyone began singing that old favorite that everyone knows, “Auld Lang Syne” to welcome the new year. It’s a tradition that has been around…well, as long as I can remember, and probably as long as most people living today can remember. That is because, on March 7, 1939, Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians recorded that song that has become such a favorite party tradition. Of course, there are a number of people who were living before 1939, and so remember a time when this song did not exist, but they are becoming fewer and fewer every year.

I think we have all been to a New Year’s Eve party, and at the stroke of midnight, everyone began singing that old favorite that everyone knows, “Auld Lang Syne” to welcome the new year. It’s a tradition that has been around…well, as long as I can remember, and probably as long as most people living today can remember. That is because, on March 7, 1939, Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians recorded that song that has become such a favorite party tradition. Of course, there are a number of people who were living before 1939, and so remember a time when this song did not exist, but they are becoming fewer and fewer every year.

With all the new music out there, and the ever-changing musical styles, it’s hard to picture a song being so timeless, but there are quite a few of them in reality. Some songs just captivate us for various reasons. When you think of the religious songs, like “Amazing Grace” or “The Old Rugged Cross,” we all know them and most of us love them, because they solidity our faith…along with many others faith songs I can think of.

Of course, there are songs from every genre that have become timeless to people who like that particular genre, but “Auld Lang Syne” has not only become timeless, but it has crossed the genre barrier to become timeless to people, no matter what type of music they like best. I think that is when you can truly call a song timeless. So the next time you find yourself singing “Auld Lang Syne” at a party, remember that it is a very old son, written in 1939, and it was brought to you by Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians. Of course, if you are like many New Year’s revelers, you will probably have too much to drink to think about or even care where the song came from. All you know is that it’s traditional to sing “Auld Lang Syne” as the clock strikes midnight on New Year’s Eve.

I have always been one to think that there is a logical explanation for everything that happens, but in the case of the Bermuda Triangle, it’s hard to stick to logical thinking, because it doesn’t follow logical lines. Over the past centuries, many ships and air planes have disappeared or met with fatal accidents in the triangular area on Atlantic ocean known as Bermuda Triangle. There are several cases in which no trace of the ships and aircraft were found even after extensive search operations were carried out for hundreds and thousands of square miles in the ocean.

I have always been one to think that there is a logical explanation for everything that happens, but in the case of the Bermuda Triangle, it’s hard to stick to logical thinking, because it doesn’t follow logical lines. Over the past centuries, many ships and air planes have disappeared or met with fatal accidents in the triangular area on Atlantic ocean known as Bermuda Triangle. There are several cases in which no trace of the ships and aircraft were found even after extensive search operations were carried out for hundreds and thousands of square miles in the ocean.

So…what happened to them. Of course, there have been many theories from a black hole to a time warp, but whatever it is, something happens to ships and planes in the Bermuda Triangle. Incidents of disappearances have been documented since the 1600s and continue today. There have been various explanations and theories behind these incidents, but in many cases the incidents are still unexplained.

In one shocking incident in 1945, a whole squadron of five training flights took off from Florida naval base under the leadership of an experienced captain. The planes never returned to the base. No one has come up with an explanation for the disappearance, and in fact, a Martin Mariner flying boat that was sent for the search operation, went missing too. None of these planes was ever heard from again.

In another incident in 1918, a large well known cargo ship went missing in the triangle area without a trace. All of the more than 300 crew members were lost. This was one of the largest lives lost case of disappearances in the Bermuda triangle. And there are many more such incidents. Theories such as methane gas blow out below the ocean causing ships to sink, electronic fog engulfing an aircraft and taking it to unknown zone, hurricanes destroying aircraft, and several other such theories try to explain such cases. They happen randomly, and not even once a year. That said, there is no way to anticipate them. For that reason, we are always shocked when  the latest incident happens. Tornado and severe weather warnings exist. We know when hurricanes are coming. We even know when snow or rain storms are coming. Unfortunately, these disappearances, like earthquakes are still very unpredictable. Nevertheless, from Christopher Columbus seeing strange lights and getting strange readings in 1492; to the disappearance of the Patriot, a ship which was carrying Theodosia Burr Alston, the daughter of former US Vice President Aaron Burr disappearing in 1812; to the latest event, the small private twin engine Mitsubishi MU-2B-40 fell victim to the Bermuda triangle on May 15, 2017 while flying from Puerto Rico. across a corner of the triangle to south Florida. The weather was fine, were no warnings…they simply vanished.

the latest incident happens. Tornado and severe weather warnings exist. We know when hurricanes are coming. We even know when snow or rain storms are coming. Unfortunately, these disappearances, like earthquakes are still very unpredictable. Nevertheless, from Christopher Columbus seeing strange lights and getting strange readings in 1492; to the disappearance of the Patriot, a ship which was carrying Theodosia Burr Alston, the daughter of former US Vice President Aaron Burr disappearing in 1812; to the latest event, the small private twin engine Mitsubishi MU-2B-40 fell victim to the Bermuda triangle on May 15, 2017 while flying from Puerto Rico. across a corner of the triangle to south Florida. The weather was fine, were no warnings…they simply vanished.