oklahoma

April 19, 1995 was a normal spring morning in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but by 9:02am, all that would change forever. This was the day that antigovernment extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols had chosen to tell the world that they didn’t like things going the way they were. The biggest problem was not that they wanted to protest, because that is their right, but it was the way they chose to protest that was completely criminal.

April 19, 1995 was a normal spring morning in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but by 9:02am, all that would change forever. This was the day that antigovernment extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols had chosen to tell the world that they didn’t like things going the way they were. The biggest problem was not that they wanted to protest, because that is their right, but it was the way they chose to protest that was completely criminal.

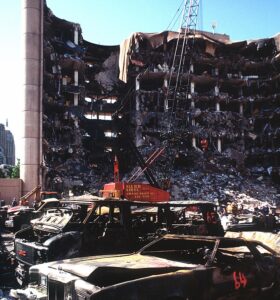

That morning, McVeigh parked a Ryder truck in front of the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building and then, he walked away. No warning was issued, because nothing was considered to be out of place, but that day about a thousand people started their day in the building, only to have their lives forever changed, or ended. The bomb went off at 9:02am, and in that moment, more than one-third of the building was destroyed, 168 people lost their lives, and about 800 were injured. The dead included 19 children in the on-site daycare facility. The blast destroyed or damaged 324 other buildings within a 16-block radius, shattered glass in 258 nearby buildings, and destroyed or burned 86 cars, causing an estimated $652 million worth of damage. In response to the attack, local, state, federal, and worldwide agencies quickly mobilized in extensive rescue. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated 11 of its Urban Search and Rescue Task Forces, consisting of 665 rescue workers who assisted in rescue and recovery operations.

The investigation moved rapidly, and within 90 minutes of the explosion, McVeigh was stopped by Oklahoma Highway Patrolman Charlie Hanger for driving without a license plate and arrested for illegal weapons possession. It seems that most criminals make mistakes that lead to their downfall. Forensic evidence quickly

linked McVeigh and Nichols to the attacks. Nichols was arrested and within days, both were charged. Michael and Lori Fortier were later identified as co-conspirators. McVeigh, a veteran of the Gulf War and a sympathizer with the US militia movement, had detonated the Ryder rental truck filled with explosives and Nichols had assisted with the bomb’s preparation. Motivated by his dislike for the US federal government and unhappy about its handling of the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993, McVeigh timed his attack to coincide with the second anniversary of the fire that ended the siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas.

linked McVeigh and Nichols to the attacks. Nichols was arrested and within days, both were charged. Michael and Lori Fortier were later identified as co-conspirators. McVeigh, a veteran of the Gulf War and a sympathizer with the US militia movement, had detonated the Ryder rental truck filled with explosives and Nichols had assisted with the bomb’s preparation. Motivated by his dislike for the US federal government and unhappy about its handling of the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993, McVeigh timed his attack to coincide with the second anniversary of the fire that ended the siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas.

I could never understand why terrorists consider it necessary to take out so many innocent lives in order to make their grievances known. The official FBI investigation was known as “OKBOMB” involved 28,000 interviews, 3.5 short tons of evidence and nearly one billion pieces of information. The bombers were tried and convicted in 1997. McVeigh was sentenced to death, and was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the US federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. Nichols was sentenced to life in prison in 2004. Michael and Lori Fortier testified against McVeigh and Nichols, in exchange for a plea-deal. Michael Fortier was sentenced to 12 years in prison for failing to warn the United States government, and Lori received immunity from prosecution in exchange for her testimony. Michael was released into witness protection in 2006.

The US Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which tightened the standards for habeas corpus in the United States n response to the bombing. It also passed legislation to increase the protection around federal buildings to deter future terrorist attacks. Prior to the September 11th attacks in 2001, the Oklahoma City bombing was the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of the United

States, other than the Tulsa race massacre. It remains one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in US history. On April 19, 2000, the Oklahoma City National Memorial was dedicated on the site of the Murrah Federal Building, commemorating the victims of the bombing. Remembrance services are held every year on April 19, at the time of the explosion.

States, other than the Tulsa race massacre. It remains one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in US history. On April 19, 2000, the Oklahoma City National Memorial was dedicated on the site of the Murrah Federal Building, commemorating the victims of the bombing. Remembrance services are held every year on April 19, at the time of the explosion.

As the United States is in the grip of a fierce snow storm, I am reminded of another snow storm that happened February 21 – 23, 1971. The storm is considered Oklahoma’s extreme storm. This blizzard buried northwestern Oklahoma under as much as three feet of snow, and that doesn’t include the drifting. The town of Buffalo was the hardest hit. They reported 23 inches of snow on the 21st alone, and a state-record snow depth of 36 inches by the morning of the 24th. The northern part of the state was just buried.

As the United States is in the grip of a fierce snow storm, I am reminded of another snow storm that happened February 21 – 23, 1971. The storm is considered Oklahoma’s extreme storm. This blizzard buried northwestern Oklahoma under as much as three feet of snow, and that doesn’t include the drifting. The town of Buffalo was the hardest hit. They reported 23 inches of snow on the 21st alone, and a state-record snow depth of 36 inches by the morning of the 24th. The northern part of the state was just buried.

Oklahoma tends to be a mild weather state, with temperatures in December, January, and February averaging in the 50s. This week is the anniversary of the 1971 blizzard, which was likely the most intense winter storm ever to hit the Sooner State, although the current storm might rival it now. With the current storm, Oklahoma is seeing temperatures averaging -6°. The prior record was in 1909 at 7°. The power company had had to implement rolling blackouts to assure that the power grids don’t fail. I don’t think they have received the amount of snow with the current storm, but the severity is very similar, when you think about it. Anytime a storm is is bad enough to shut things down, especially the power, it is severe.

When the blizzard of 1971 finally ended, 36 inches of snow was measured in Buffalo, which was the state’s record for the highest snowfall total, but the snow drifts measured as high as 20 feet tall. While northwestern Oklahoma was hit very hard, just a short distance to the west in the Oklahoma Panhandle, only light snow fell with Boise City receiving only 3 inches and only 2 inches in Kenton. The 1971 storm put ranchers in a precarious position until C-124s from the Oklahoma Air National Guard dropped 150 tons of hay to stranded Oklahoma cattle. Local cattleman flew along with the aircraft to guide the aircrews to the stranded cattle. The massive loss numbers of 15,000 in livestock accounted for much of the $2 million in damages.

The vicious storm became known as the 84-hour blizzard. It actually occurred across the eastern half of the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles. The storm his the worst un Oklahoma, but in the region, 8 deaths were reported…7 in Pampa, 1 in the Oklahoma Panhandle. The average drifts were 10 to 20 feet. Storms like these will not likely be soon forgotten, if they are ever forgotten. People are really never prepared for such cold temperatures and so much snow in the southern states. We can try to prepare, but when year after year goes by without such a sever storm, we soon become complacent, until the next one hits us, that is.

The vicious storm became known as the 84-hour blizzard. It actually occurred across the eastern half of the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles. The storm his the worst un Oklahoma, but in the region, 8 deaths were reported…7 in Pampa, 1 in the Oklahoma Panhandle. The average drifts were 10 to 20 feet. Storms like these will not likely be soon forgotten, if they are ever forgotten. People are really never prepared for such cold temperatures and so much snow in the southern states. We can try to prepare, but when year after year goes by without such a sever storm, we soon become complacent, until the next one hits us, that is.

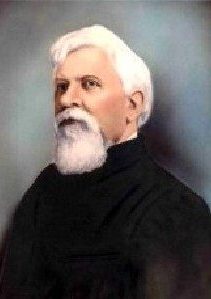

Unfortunately, there are among us, people who are corrupt and ruthless, and sometimes, things happen because of corruption, anger, or even stupidity. William Tilghman was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa on July 4, 1854, at the height of the “Wild West” era. He was a man who wanted something more, so at 16 years old, he moved west. As sometimes happened, men who went west, toyed with the wild life that was brought about by the lawless area. Tilghman was no different. He fell in with a bad crowd of young men who stole horses from the Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided that rustling was too dangerous and settled in Dodge City, Kansas, where he briefly served as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. He was arrested twice for alleged train robbery and rustling, but the charges did not stick. It was a shaky start, but Tilghman gradually built a reputation as an honest and respectable young man in Dodge City. Before long, he became the deputy sheriff of Ford County, Kansas. Later, he was offered and accepted the job of the marshal of Dodge City…a real life Matt Dillon, from Gunsmoke.

Unfortunately, there are among us, people who are corrupt and ruthless, and sometimes, things happen because of corruption, anger, or even stupidity. William Tilghman was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa on July 4, 1854, at the height of the “Wild West” era. He was a man who wanted something more, so at 16 years old, he moved west. As sometimes happened, men who went west, toyed with the wild life that was brought about by the lawless area. Tilghman was no different. He fell in with a bad crowd of young men who stole horses from the Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided that rustling was too dangerous and settled in Dodge City, Kansas, where he briefly served as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. He was arrested twice for alleged train robbery and rustling, but the charges did not stick. It was a shaky start, but Tilghman gradually built a reputation as an honest and respectable young man in Dodge City. Before long, he became the deputy sheriff of Ford County, Kansas. Later, he was offered and accepted the job of the marshal of Dodge City…a real life Matt Dillon, from Gunsmoke.

Tilghman was one of the first men into the territory when Oklahoma opened to settlement in 1889, and he became a deputy US marshal for the region in 1891. In the late 19th century, lawlessness was still very much a part of Oklahoma. Tilghman helped to bring order the to area by ridding Oklahoma by capturing some of the most notorious bandits of the day. While locking up many criminals, Tilghman, nevertheless, managed to earn a well-deserved reputation for treating even the worst criminals fairly and protecting the rights of the unjustly accused. Any man, who found himself in Tilghman’s custody, knew he was safe from angry vigilante mobs,  because Tilghman had little tolerance for those who took the law into their own hands. In 1898, a wild mob lynched two young Indians who were falsely accused of raping and murdering a white woman. Tilghman arrested and secured prison terms for eight of the mob leaders and captured the real rapist-murderer.

because Tilghman had little tolerance for those who took the law into their own hands. In 1898, a wild mob lynched two young Indians who were falsely accused of raping and murdering a white woman. Tilghman arrested and secured prison terms for eight of the mob leaders and captured the real rapist-murderer.

In 1924, after serving a term as an Oklahoma state legislator, making a movie about his frontier days, and serving as the police chief of Oklahoma City, Tilghman might well have been expected to quietly retire. However, it was the height of the Prohibition era, and the old lawman was unable to hang up his gun. He still felt a calling to keep law and order in his town. He accepted a job as city marshal in Cromwell, Oklahoma. On November 1, 1924, William Tilghman, who was known to both friends and enemies alike as “Uncle Billy” was murdered by a corrupt prohibition agent who resented Tilghman’s refusal to ignore local bootlegging operations. The Prohibition officer was drunk, and in his anger, made the worst mistake of his life.

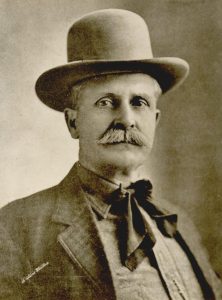

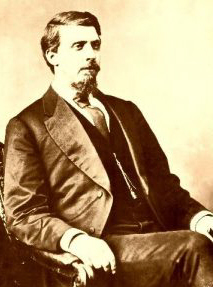

The Indian Territory, which is now Oklahoma, in 1875, was populated by cattle and horse thieves, whiskey peddlers, and bandits who sought refuge in the untamed territory that was free of a “White Man’s Court.” There was one court with jurisdiction over Indian Territory was the U.S. Court for the Western District of Arkansas located in Fort Smith, Arkansas, which was situated on the border of Western Arkansas and Indian Territory. Judge Isaac Parker, who was often called the “Hanging Judge,” from Fort Smith, Arkansas ruled over the lawless land of Indian Territory in the late 1800s. He was determined to stop the pollution of the Indian Territory that was the outlaws who thought they could outrun the law.

The Indian Territory, which is now Oklahoma, in 1875, was populated by cattle and horse thieves, whiskey peddlers, and bandits who sought refuge in the untamed territory that was free of a “White Man’s Court.” There was one court with jurisdiction over Indian Territory was the U.S. Court for the Western District of Arkansas located in Fort Smith, Arkansas, which was situated on the border of Western Arkansas and Indian Territory. Judge Isaac Parker, who was often called the “Hanging Judge,” from Fort Smith, Arkansas ruled over the lawless land of Indian Territory in the late 1800s. He was determined to stop the pollution of the Indian Territory that was the outlaws who thought they could outrun the law.

Judge Isaac Parker was born in a log cabin outside Barnesville, Belmont County, Ohio on October 15, 1838. The youngest son of Joseph and Jane Parker. As a boy, Isaac helped out on the farm, but never really cared for that type of work. He attended the Breeze hill primary school and then the Barnesville Classical Institute. Knowing he wanted more, he decided to go for a higher education. To help pay for it, he taught students in a country primary school. When he was 17 he decided to study law, his legal training consisting of a combination of apprenticeship and self study. Reading law with a Barnesville attorney, he passed the Ohio bar exam in 1859 at the age of 21. During this period of his life, he met and married Mary O’Toole and the couple had two sons, Charles and James. Over the years, Parker built a reputation for being an honest lawyer and a much respected leader of the community.

After Parker passed the bar, he decided to head west, ending up in Saint Joseph, Missouri a bustling Missouri River port town. He went to work for his uncle, D.E. Shannon, becoming a partner in the Shannon and Branch legal firm. By 1861, he was working on his own in both the municipal and county criminal courts. In April of 1861, he won the election as City Attorney. He was re-elected to the post for the next two years. In 1864,  Isaac Parker ran for county prosecutor of the Ninth Missouri Judicial District and in the fall of that same year, he served as a member of the Electoral College, casting his vote for Abraham Lincoln. During a political career that included a six-year term as judge of the Twelfth Missouri Circuit in 1868, Parker would soon gain the experience that he would later use as the ruling Judge over the Indian Territory.

Isaac Parker ran for county prosecutor of the Ninth Missouri Judicial District and in the fall of that same year, he served as a member of the Electoral College, casting his vote for Abraham Lincoln. During a political career that included a six-year term as judge of the Twelfth Missouri Circuit in 1868, Parker would soon gain the experience that he would later use as the ruling Judge over the Indian Territory.

After the Civil War, the number of outlaws had grown, wrecking the relative peace of the five civilized tribes that lived in Indian Territory. By the time Parker arrived at Fort Smith, the Indian Territory had become known as a very bad place, where outlaws thought the laws did not apply to them and terror reigned. Parker replaced Judge William Story, whose tenure had been marred by corruption, after arriving in Fort Smith on May 4, 1875. At the age of 36, Judge Parker was the youngest Federal judge in the West. Holding court for the first time on May 10, 1875, eight men were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Judge Parker held court six days a week, often up to ten hours each day and tried 91 defendants in his first eight weeks on the bench. He was determined to clean up the Indian Territory, single handedly if necessary. In that first summer, eighteen persons came before him charged with murder and 15 were convicted. Eight of them were sentenced to die on the gallows on September 3, 1875. However, only six would be executed as one was killed trying to escape and a second had his sentence commuted to life in prison because of his young age.

The day of the September 3, 1875 hanging was a media circus, and because of all the attention, everyone knew that the once corrupt court was functioning properly again. Parker’s critics dubbed him the “Hanging Judge” and called his court the “Court of the Damned.” They thought Judge Parker was too harsh. The Fort  Smith Independent was the first newspaper to report the event on September 3, 1875 with the large column heading reading: “Execution Day!!” Other newspapers around the country reported the event a day later. These press reports shocked people throughout the nation. “Cool Destruction of Six Human Lives by Legal Process” screamed the headlines. Of the six felons, three were white, two were Native American and one was black. When the preliminaries were over, the six were lined up on the scaffold while executioner George Maledon adjusted the nooses around their necks. The trap was sprung all six died at once at the end of the ropes. The event solidified Judge Parker’s nickname for all time. In 21 years on the bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases, 344 of which were capital crimes. 9,454 cases resulted in guilty pleas or convictions. Over the years, Judge Parker sentenced 160 men to death by hanging, though only 79 of them were actually hanged. The rest died in jail, appealed or were pardoned. Judge Parker died on November 17, 1896.

Smith Independent was the first newspaper to report the event on September 3, 1875 with the large column heading reading: “Execution Day!!” Other newspapers around the country reported the event a day later. These press reports shocked people throughout the nation. “Cool Destruction of Six Human Lives by Legal Process” screamed the headlines. Of the six felons, three were white, two were Native American and one was black. When the preliminaries were over, the six were lined up on the scaffold while executioner George Maledon adjusted the nooses around their necks. The trap was sprung all six died at once at the end of the ropes. The event solidified Judge Parker’s nickname for all time. In 21 years on the bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases, 344 of which were capital crimes. 9,454 cases resulted in guilty pleas or convictions. Over the years, Judge Parker sentenced 160 men to death by hanging, though only 79 of them were actually hanged. The rest died in jail, appealed or were pardoned. Judge Parker died on November 17, 1896.

Little is known about the early life of William Coe, always known as “Captain” Bill Coe, except that he was a southern boy and worked as a carpenter and stonemason…until he turned to a life of crime, that is. It is believed that he fought with the Confederates during the Civil War, which is probably where he came to be known as the “Captain,” but there is no solid poof of this.

Little is known about the early life of William Coe, always known as “Captain” Bill Coe, except that he was a southern boy and worked as a carpenter and stonemason…until he turned to a life of crime, that is. It is believed that he fought with the Confederates during the Civil War, which is probably where he came to be known as the “Captain,” but there is no solid poof of this.

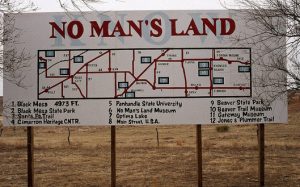

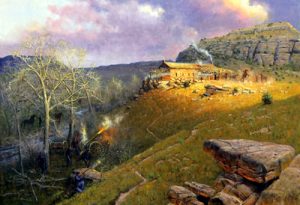

“Captain” Bill Coe arrived in the Oklahoma Panhandle about 1864, having decided to settle in that area. The area was referred to as “No Man’s Land”t that time. The strip of land, measuring some 35 miles wide by 168 miles long, was not included in any state and therefore left without any law and order. It was a haven for outlaws for years , and William Coe took advantage of that situation. Along a long high ridge jutting southwest from a large mesa near the town of Kenton, Oklahoma, “Captain” Coe built a “fortress” to protect himself and his gang of some 30 to 50 members, who primarily rustled cattle, horses, sheep, and mules. Coe’s headquarters, made of rock walls that were about three feet thick. There were portholes for protection rather than windows, as well as a fully stocked bar, living quarters for his men, and a number of ladies of the evening for their entertainment. Coe’s fortress became known as “Robber’s Roost.”

These men raided ranches and military installations from Fort Union, New Mexico to the south, Taos, New Mexico to the west, and as far north as Denver, Colorado to make their living. They also robbed freight caravans traveling along the Santa Fe Trail, as well as area ranches. Coe’s gang hid the stock in a canyon about five miles northwest of their hide-out. They built a fully equipped blacksmith shop, which contained all the tools necessary to maintain the herds, as well as changing the brands. When all hint of the previous owners were removed, the gang then moved the herds into Missouri or Kansas to sell. They got away with their lawlessness for several years…then they made a major mistake when they raided a large sheep ranch in Las Vegas, New Mexico in 1867, killing two men before making off with the herd to Pueblo, Colorado. They had been wanted men before, but these murders put Coe and his men on the “wanted list” like never before. Soon the U.S. Army from Fort Lyon, Colorado were pursuing them.

The Army attacked the Robber’s Roost fortress with a cannon. The walls crumbled like pebbles. The attack killed and wounded several of the outlaws. Though Coe and others were able to escape, several outlaws that weren’t killed in the battle were hanged on the spot, while others were arrested and taken back to Colorado. Coe continued his crimes and his freedom for about a year, hiding out in a small, now abandoned settlement of Madison, New Mexico, near Folsom. Then, while he was sleeping in a woman’s bunkhouse, her 14-year-old son rode from the ranch and contacted area soldiers, who soon returned and arrested Coe. The fugitive was then taken to Pueblo, Colorado to await trial and along the way, allegedly said, “I never figured to be “outgeneraled” by a woman, a pony, and a boy.”

Before Coe could be brought to trial, vigilantes took matters into their own hands on the evening of July 20, 1868. They forcibly removed him from the jail, loaded him into a wagon, and hung him on a cottonwood tree on the bank of Fountain Creek, while he was still handcuffed and shackled. The next day, his body was discovered and buried under the tree that he was hanged from. Years later, when a new road was being built in the vicinity of Fourth Street in Pueblo, workers found the skeletal remains of what is believed to have been Coe’s.

The Old West was a wild, untamed place, and the people who lived there had to be tough as nails too. During that time, the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, was considered the most violent of the American territories. Along with the Indians, it served as home to hundreds of outlaws from around the country. These were hardened criminal men, accused of murder, rape, robbery, arson, adultery, bribery, and numerous other crimes. They headed to the Indian Territory, looking for a place to hideout…a place where the lawmen couldn’t follow. The Indian Territory was without law enforcement with the exception of the Indian Nations’ police forces, who had no jurisdiction over the many criminals who had taken flight from other states. It left the outlaws in a place of sweet freedom, from both types of law.

The Old West was a wild, untamed place, and the people who lived there had to be tough as nails too. During that time, the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, was considered the most violent of the American territories. Along with the Indians, it served as home to hundreds of outlaws from around the country. These were hardened criminal men, accused of murder, rape, robbery, arson, adultery, bribery, and numerous other crimes. They headed to the Indian Territory, looking for a place to hideout…a place where the lawmen couldn’t follow. The Indian Territory was without law enforcement with the exception of the Indian Nations’ police forces, who had no jurisdiction over the many criminals who had taken flight from other states. It left the outlaws in a place of sweet freedom, from both types of law.

Then Judge Isaac Parker was appointed to the Western Judicial District of Arkansas, which included Indian Territory. All that sweet freedom was about to end. Parker decided to bring law and order to the Indian Territory…or at least to the criminal element of it. He commanded about 200 deputy marshals to “clean up” the lawless territory. It was a noble idea that would take years to accomplish, as the deputies struggled to cover some 74,000 square miles in their search for hundreds of wanted fugitives. The occupation of a U.S. Deputy Marshal courted constant danger, so much so that between 1872 and 1896, over 100 deputies died enforcing the law throughout the territory. A number of men made names for themselves working as U.S. Marshals in the Indian Territory. Men such as Heck Thomas, Bass Reeves, Bill Tilghman, Chris Madsen, and dozens of others.

There were also a number of other U.S. Marshals who, more quietly made names for themselves, mainly because they were women. I think that as a woman, I would not be so inclined to head into Indian Territory in those days to “clean up” the place. Women have long been considered a part of the “clean up” crew, but most of the time, it was as homemakers. I don’t think anyone thought they could be successful law enforcement officers…at least not in those days.

One of these brave women was F.M. Miller, who was appointed as a U.S. Deputy Marshal out of the federal court at Paris, Texas in 1891. When she was commissioned, she was the only female deputy working in Indian Territory. She was known to have accompanied Campbell on all his trips. During her tenure, she was mentioned in several newspaper articles including the Fort Smith Elevator on November 6, 1891 that described here as: “a dashing brunette of charming manners.” The article continued by stating: “The woman carries a pistol buckled around her and has a Winchester strapped to her saddle. She is an expert shot and a superb horsewoman, and brave to the verge of recklessness. It is said that she aspires to win a name equal to that of Belle Starr, differing from her by exerting herself to run down criminals and in the enforcement of the law.”

Another article appeared a couple of weeks later in the Muskogee Phoenix on November 19, 1891, which said that she had the reputation of being a fearless and efficient officer and had locked up more than a few offenders. The article continued: “Miss Miller is a young woman of prepossessing appearance, wears a cowboy hat and is always adorned with a pistol belt full of cartridges and a dangerous looking Colt pistol which she knows how to use. She has been in Muskogee for a few days, having come here with Deputy Marshal Cantrel, a guard with some prisoners brought from Talahina. Regarding Miss. Miller’s unique position as Deputy U.S. Marshal, another newspaper commented, “Hopefully in the future, there will be more information on this colorful peace officer.”

Another female U.S Marshal in Indian Territory who showed bravery and skill in her job was a young woman named Ada Curnutt. The daughter of a Methodist minister, Ada Curnutt moved to the Oklahoma Territory with her sister and brother-in-law shortly after it opened for settlers. The 20 year old soon found work as the Clerk of the District Court in Norman, Oklahoma and as a Deputy Marshal to U.S. Marshal William Grimes. Her most famous arrest occurred in March, 1893 when she received a telegram from Grimes, instructing her to send a deputy to Oklahoma City to bring in two notorious outlaws named Reagan and Dolezal who were wanted for forgery. I seriously doubt that Grimes meant for her to go, but all the other deputies were out in the field so Curnutt stepped up to the responsibility. She quickly boarded a train for Oklahoma City. When she arrived she discovered that the two men were in a saloon and quickly made her way there. Upon her arrival she asked a man on the street to go in and tell them that a lady needed to see them outside. The outlaws eagerly went out to meet her. When the two emerged, Ada read the warrants to them and stated that they were under arrest. Heavily armed, the two men laughed at the young woman and thinking it was a joke. They stupidly allowed her to place handcuffs over their wrists. When the captives began to realize that the joke was on them, Curnutt announced to the crowd gathered around them that she was prepared to deputize every man to aide her, if needed. As it turns out, it was not necessary, as she escorted them to the the train station and telegraphed the marshal’s office in Guthrie that she was bringing them in. She was 24 years old at the time. The two forgers  were soon tried and convicted. “Like all deputies of her era, she had to be extremely tough and ready to face a wide range of situations,” the U.S. Marshals Service wrote of Carnutt.

were soon tried and convicted. “Like all deputies of her era, she had to be extremely tough and ready to face a wide range of situations,” the U.S. Marshals Service wrote of Carnutt.

While it was unusual, there were a number of women in law enforcement, even before it was widely accepted as normal. All these women forged the way for the many women we have in law enforcement, and even in the military today. these women may have been the “clean up” crew, but they were a tough as nail clean up crew, and they made, and continue to make, history in the field of law enforcement, and in the military.

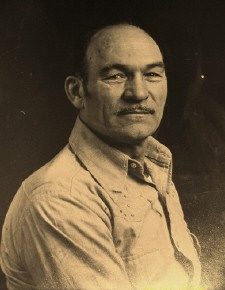

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

“Al” Spencer became a criminal as the era of horseback riding was coming to an end, and modern motorized criminals were just getting started. That fact, made Spencer an almost forgotten outlaw. Spencer began his career in crime by getting caught stealing cattle in his early 30s. Then in 1919, he and two men burglarized a clothing store in Neodesha, Kansas. Detectives recovered most of the stolen property and arrested Spencer in La Junta, Colorado. The Kansas court convicted and sentenced him to five years in prison. Then the Oklahoma authorities gained custody of Spencer so they could try him on charges of cattle theft. Spencer pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three to 10 years in the Oklahoma penitentiary at McAlester. He began serving his sentence in March 1920. If you ask me, he should have stuck to farming, because he wasn’t very good at crime. Spencer became friends with another convict named Henry Wells and learned a great deal about crime…becoming better, I suppose…at least as long has Wells was with him. In the 1920s, it was not unusual for Oklahoma governors to grant convicts a leave of absence from prison…even some convicted of major crimes. Spencer was given leave on July 26, 1921, to attend to “some family business” supposedly. He returned to McAlester a month later and became a trustee and was trained to be an electrician. Early in 1922, he was assigned to do electrical work outside the prison in someone’s home. He completed the work, but then he packed up his tools and didn’t return to the prison.

Within a month, Spencer had hooked up with Silas Meigs, who had escaped in a similar fashion from the prison. The pair robbed the American National Bank at Pawhuska, making a “major” haul of $147. Soon the two men robbed a bank at Broken Bow, and this one netted a little more profit. They escaped with between $7,000 and $8,500. They forced a motorist to take them three miles north of town where they had left two horses. The robbers rode away. A few days later Meigs was killed in a gun battle with lawmen northwest of Bartlesville, where he had gone to visit his brother. Spencer remained hidden in the Osage Hills, a vast stretch of country with timber, rocky canyons and thickets of almost impenetrable scrub oak. Friends and relatives brought him food. Spencer later joined up with Henry Wells and two other criminals and robbed a bank at Pineville in  southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

Exactly how many banks were robbed by Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer during the eighteen months following his escape is not known. Evidence suggests he probably robbed at least 20 banks in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas. The end of his crime spree came on a Saturday evening, September 15, 1923, when he was shot and killed. There is, however, debate on just how he was killed. U.S. Marshal Alva McDonald, a veteran lawman and personal friend of Teddy Roosevelt, claimed he and other lawmen shot Spencer just south of Caney, Kansas. Another account reported that Spencer was killed about five miles north of Coffeyville, Kansas. The third account came from outlaw Henry Wells’ autobiography. Wells claims that Stanley Snyder, a friend of Spencer’s, killed the outlaw with a shotgun while Spencer was eating supper. Some friend he must have been, but then I guess there is no honor among thieves. Al Spencer’s outlaw days were over, nevertheless, and a new breed of bad men soon took his place using only automobiles. Spencer was the last major Oklahoma outlaw to use horses in his crimes.

When I think of Tornado Alley, Oklahoma is always among the states that come to mind, but I didn’t know which tornado would be considered the worst one in the states history. Nor did I know that the 1947 Woodward Tornado would continue to hold that status year after year. The most deadly tornado to ever strike within the borders of the state of Oklahoma occurred on Wednesday, April 9, 1947 in the city of Woodward, and across Texas and Kansas. The Woodward tornadic storm actually began in the Texas Panhandle that afternoon, and produced at least six tornadoes along a 220 mile path that stretched from White Deer, Texas, northeast of Amarillo, to Saint Leo, Kansas, west of Wichita.

When I think of Tornado Alley, Oklahoma is always among the states that come to mind, but I didn’t know which tornado would be considered the worst one in the states history. Nor did I know that the 1947 Woodward Tornado would continue to hold that status year after year. The most deadly tornado to ever strike within the borders of the state of Oklahoma occurred on Wednesday, April 9, 1947 in the city of Woodward, and across Texas and Kansas. The Woodward tornadic storm actually began in the Texas Panhandle that afternoon, and produced at least six tornadoes along a 220 mile path that stretched from White Deer, Texas, northeast of Amarillo, to Saint Leo, Kansas, west of Wichita.

The town of Woodward, Oklahoma was hit head on, and was nearly wiped off the map by the powerful tornado. More than 100 people died in Woodward, and 80 more lost their lives  elsewhere in the series of twisters that hit the heartland of the United States that day. The tornado that struck Woodward actually began near Canadian, Texas. It moved northeast, continuously on the ground for about 100 miles, ending in Woods County, Oklahoma, west of Alva. The tornado was massive, measuring up to 1.8 miles wide, and moved along its path at speeds of about 50 miles per hour. It first struck Glazier and Higgins in the Texas Panhandle, bringing devastation to both towns and killing at least 69 people in Texas before crossing into Oklahoma. In Ellis County, Oklahoma, the tornado did not strike any towns, passing to the southeast of Shattuck, Gage, and Fargo. Nevertheless, while no towns were struck, 60 farms and ranches were destroyed and 8 people were killed and 42 injured. In Woodward County, one death was reported near Tangier.

elsewhere in the series of twisters that hit the heartland of the United States that day. The tornado that struck Woodward actually began near Canadian, Texas. It moved northeast, continuously on the ground for about 100 miles, ending in Woods County, Oklahoma, west of Alva. The tornado was massive, measuring up to 1.8 miles wide, and moved along its path at speeds of about 50 miles per hour. It first struck Glazier and Higgins in the Texas Panhandle, bringing devastation to both towns and killing at least 69 people in Texas before crossing into Oklahoma. In Ellis County, Oklahoma, the tornado did not strike any towns, passing to the southeast of Shattuck, Gage, and Fargo. Nevertheless, while no towns were struck, 60 farms and ranches were destroyed and 8 people were killed and 42 injured. In Woodward County, one death was reported near Tangier.

The storm occurred when a cold front from Siberia met a warm and moist stream of air from the Gulf of Mexico,  and into Texas. By the time it reached Woodward, some estimated that it was as big as two miles wide. As the storm moved through Woodward, 200 residential blocks were completely leveled and nearly 1,000 homes were razed. Fires broke out in several spots but the heavy rains kept them under control. In all, 107 people were killed in Woodward and many more were injured. The devastating tornado then continued on to Kansas, where significant damage was done but no one was killed. When looting was reported in the areas hit by the tornado, the National Guard was called in to restore order. Army barracks were used to house the homeless until their homes could be rebuilt. Damage caused by this event totaled about $9,700,000.

and into Texas. By the time it reached Woodward, some estimated that it was as big as two miles wide. As the storm moved through Woodward, 200 residential blocks were completely leveled and nearly 1,000 homes were razed. Fires broke out in several spots but the heavy rains kept them under control. In all, 107 people were killed in Woodward and many more were injured. The devastating tornado then continued on to Kansas, where significant damage was done but no one was killed. When looting was reported in the areas hit by the tornado, the National Guard was called in to restore order. Army barracks were used to house the homeless until their homes could be rebuilt. Damage caused by this event totaled about $9,700,000.

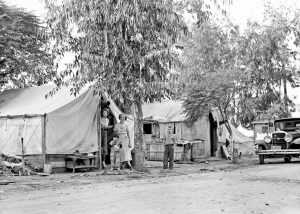

The “Dust Bowl” was an environmental disaster that hit the Midwest in the 1930s. A combination of a severe water shortage and harsh farming techniques caused the disaster. Some scientists believe it was the worst drought in North America in 300 years. The lack of rain killed the crops that kept the soil in place. When winds blew, they raised enormous clouds of dust. It deposited mounds of dirt on everything, even covering houses. With the Dust Bow came the failure of many farms in the Midwest, and the people had no choice but to move, in order to find a way to make a living.

The “Dust Bowl” was an environmental disaster that hit the Midwest in the 1930s. A combination of a severe water shortage and harsh farming techniques caused the disaster. Some scientists believe it was the worst drought in North America in 300 years. The lack of rain killed the crops that kept the soil in place. When winds blew, they raised enormous clouds of dust. It deposited mounds of dirt on everything, even covering houses. With the Dust Bow came the failure of many farms in the Midwest, and the people had no choice but to move, in order to find a way to make a living.

I suppose that the invasion that followed might have been similar to the current refugees. It wasn’t just one family that moved, but hundreds of families. Los Angeles Police Chief James E. Davis, seeking to halt the “invasion” of dust-bowl Depression refugees in February, 1936, declared a “Bum Blockade” to stop the mass emigration of poverty stricken families fleeing from the dust-torn states of the Midwest. These days, he would have met with severe criticism, not so much for the blockade, as for the name of the blockade.

By 1934, 75% of the United States was severely affected by this terrible drought. The region most affected was the Great Plains, and included more than 100 million acres, centered in Oklahoma, the Texas Panhandle, Kansas, and parts of Colorado and New Mexico. These millions of acres of farmland became useless and soon, hundreds of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes. Many of these destitute families packed up their belongings and migrated west, hoping to find work and a better life, about 200,000 of which were California bound. Instead of finding the promised land of their dreams, however, they found that the available labor pool was vastly disproportionate to the number of job openings that could be filled. Migrants who found employment soon learned that this surplus of workers caused a significant reduction in the going wage rate, and even when the entire family worked, they were unable to support themselves.

Many set up “ditchbank” camps along irrigation canals in the farmers’ fields, which brought with them poor sanitary conditions and created a public health problem. And, of those who could find work in agriculture, it did not put an end to their travels. Instead, their lives were characterized by transience, if they wanted to maintain a steady income, which required them to follow the various harvests around the state. In the meantime, California was overwhelmed, trying to figure out how to absorb as many as 6,000 migrants crossing its borders daily. Also feeling the effects of the Depression, California infrastructures were already overburdened, and the steady stream of newly arriving migrants was more than the system could bear. Though these refugees came from a number of states, Californians often lumped them together as “Okies” or “Arkies,” who became the butt of derogatory jokes and the focus of political campaigns in which candidates made them the scapegoat for a shattered economy. They were accused of many crimes, as well as shiftlessness, lack of ambition, school overcrowding and stealing jobs from native Californians.

California’s Indigent Act was passed in 1933, which made it a crime to bring indigent persons into the state, Davis contended that his men needed no special approval because “any officer has the authority to enforce the state law.” Asking border-county sheriffs to deputize his officers, most complied. However, some refused, including Modoc County, who forced 14 LAPD officers to leave after they turned away local residents trying to

return home. On August 24, 1935, the Los Angeles Herald-Express ran an article warning emigrants to stay away from California. It read: Stay Away From California: Warning To Transient Hordes. Those days were very different from the California of today, and not in a good way. I don’t agree with derogatory name calling, but common sense tells us that sometimes you have to try to stop a flood, even if it’s a flood of people.

return home. On August 24, 1935, the Los Angeles Herald-Express ran an article warning emigrants to stay away from California. It read: Stay Away From California: Warning To Transient Hordes. Those days were very different from the California of today, and not in a good way. I don’t agree with derogatory name calling, but common sense tells us that sometimes you have to try to stop a flood, even if it’s a flood of people.

In years gone by, US Route 66 was also known as the Will Rogers Highway, the Main Street of America, or the Mother Road. It was one of the original highways within the US Highway System. US Highway 66 was established on November 11, 1926, with road signs erected the following year. The highway became one of the most famous roads in the United States, and originally ran from Chicago, Illinois, through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before ending at Santa Monica, California, covering a total of 2,448 miles. It was highlighted by both the hit song “(Get Your Kicks) on Route 66” and the Route 66 television show in the 1960s, and later, “Wild Hogs.” After 59 years, on June 27, 1985, when the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials decertified the road and removed all its highway signs, and the famous Route 66 entered the realm of history.

In years gone by, US Route 66 was also known as the Will Rogers Highway, the Main Street of America, or the Mother Road. It was one of the original highways within the US Highway System. US Highway 66 was established on November 11, 1926, with road signs erected the following year. The highway became one of the most famous roads in the United States, and originally ran from Chicago, Illinois, through Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona before ending at Santa Monica, California, covering a total of 2,448 miles. It was highlighted by both the hit song “(Get Your Kicks) on Route 66” and the Route 66 television show in the 1960s, and later, “Wild Hogs.” After 59 years, on June 27, 1985, when the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials decertified the road and removed all its highway signs, and the famous Route 66 entered the realm of history.

The idea of building a highway along this route was first mentioned in Oklahoma in the mid-1920s. It was a way to link Oklahoma to cities like Chicago and Los Angeles. Highway Commissioner Cyrus Avery said that it would also be a way of diverting traffic from Kansas City, Missouri and Denver. In 1926, the highway earned its official designation as Route 66. The diagonal course of Route 66 linked hundreds of mostly rural communities to the cities along its route. This was to allow farmers to have an easy transport route for grain and other types of produce for distribution to the cities. In the 1930s, the long-distance trucking industry used it as a way of competing with the railroad for dominance in the shipping market.

During the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s, Route 66 was the scene of a mass westward migration, when more than 200,000 people traveled east from poverty-stricken, drought-ridden areas of California. John Steinbeck immortalized the highway in his classic 1939 novel “The Grapes of Wrath.” Beginning in the 1950s, the building of a massive system of interstate highways made older roads increasingly obsolete, and by 1970, modern four lane

highways had bypassed nearly all sections of Route 66. In October 1984, Interstate 40 bypassed the last original stretch of Route 66 at Williams, Arizona. According to the National Historic Route 66 Federation, drivers can still use 85 percent of the road, and Route 66 has become a destination for tourists from all over the world. After watching Wild Hogs, Bob and I became two of the many tourists who did drive a little bit of it when we drove to Madrid, New Mexico as part of our vacation, doing all the touristy things.

highways had bypassed nearly all sections of Route 66. In October 1984, Interstate 40 bypassed the last original stretch of Route 66 at Williams, Arizona. According to the National Historic Route 66 Federation, drivers can still use 85 percent of the road, and Route 66 has become a destination for tourists from all over the world. After watching Wild Hogs, Bob and I became two of the many tourists who did drive a little bit of it when we drove to Madrid, New Mexico as part of our vacation, doing all the touristy things.