World War II

Curon Venosta was a village in northern Italy located in South Tyrol. Curon Venosta’s disappearance was not a mystery. The village suffered the same fate as numerous other towns over the years. The alpine village fell victim to the formation of a large man-made lake. The land was purchased and alpine village inundated shortly after World War II due to the construction of a dam. The officials had decided that they would join two smaller per-existing lakes into one large man-made lake.

Curon Venosta was a village in northern Italy located in South Tyrol. Curon Venosta’s disappearance was not a mystery. The village suffered the same fate as numerous other towns over the years. The alpine village fell victim to the formation of a large man-made lake. The land was purchased and alpine village inundated shortly after World War II due to the construction of a dam. The officials had decided that they would join two smaller per-existing lakes into one large man-made lake.

Originally, plans were made to make a smaller artificial lake dated back to the year 1920. Then, in July 1939 a new plan was introduced for a 75 foot deep lake, which would unify two natural lakes. The point of joining the lakes together was to create a hydroelectric dam. The creation of the dam started in April 1940, but due to World War II and local resistance, the project did not finish until July 1950.

The new larger lake had a capacity of 120 million cubic meters, making this artificial lake the largest lake in the province and its surface area of 2.5 square miles makes it also the largest lake above .6 miles in the Alps. During the project, 163 houses and nearly 1.300 acres of cultivated land was flooded. The structures were not torn down, they were just vacated and flooded. The entire village of Curon Venosta is still down there, filled with sand. All that remains of the old Curon Venosta is the tip of a bell tower, standing in the middle of the lake. As a consolation to the angry villagers, a new village was built at a higher elevation.

The 14th-century church steeple was left to stand as a historic memorial, and was restored in 2009 to repair cracks. During the winter months, the lake freezes over, and people enjoy a walk right up to the spire. A legend

says that during winter one can still hear church bells ring, but in reality the bells were removed from the tower on July 18, 1950. The village of Curon Venosta was once a village of hundreds of people, and then it was sacrificed in the name of energy. Now, 70 years later, the lake was drained to perform some repairs to the dam. The people living in the area talked about how strange it was to walk in the ruins of the village they hadn’t seen in seven decades. Of course the sight of the village was temporary, and when the work was done, the village disappeared once again.

says that during winter one can still hear church bells ring, but in reality the bells were removed from the tower on July 18, 1950. The village of Curon Venosta was once a village of hundreds of people, and then it was sacrificed in the name of energy. Now, 70 years later, the lake was drained to perform some repairs to the dam. The people living in the area talked about how strange it was to walk in the ruins of the village they hadn’t seen in seven decades. Of course the sight of the village was temporary, and when the work was done, the village disappeared once again.

Through the years, Russia, also known as the Soviet Union and the USSR, has been sometimes ally and sometimes enemy of the United States. World War I and World War II found the Soviet Union once again on the side of good as a part of the Allied Forces. The main countries in the Allied powers of World War I were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire. The main Allied powers of World War II were France, Great Britain, the United States, China, and the Soviet Union. So in these two wars anyway, the United States and Russia were on the same side. The three principal partners in the Axis alliance in World War II were Germany, Italy, and Japan. They were joined by Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Thailand, who also signed the Tri-Partite Pact as member states.

Through the years, Russia, also known as the Soviet Union and the USSR, has been sometimes ally and sometimes enemy of the United States. World War I and World War II found the Soviet Union once again on the side of good as a part of the Allied Forces. The main countries in the Allied powers of World War I were France, the British Empire and the Russian Empire. The main Allied powers of World War II were France, Great Britain, the United States, China, and the Soviet Union. So in these two wars anyway, the United States and Russia were on the same side. The three principal partners in the Axis alliance in World War II were Germany, Italy, and Japan. They were joined by Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Thailand, who also signed the Tri-Partite Pact as member states.

On May 12, 1942, Soviet forces under the command of Marshal Semyon Timoshenko attacked the German 6th  Army from a vulnerable point established during the winter counter-offensive. After a promising start, the offensive was stopped on May 15th by massive airstrikes. There were a number of critical Soviet errors by several staff officers and by Joseph Stalin, who failed to accurately estimate the 6th Army’s potential and overestimated their own newly raised forces, facilitated a German pincer attack on May 17th which cut off three Soviet field armies from the rest of the front by May 22nd. The Soviet Army was hemmed into a narrow area, and the 250,000-strong Soviet force inside the pocket was exterminated from all sides by German armored, artillery, and machine gun firepower, as well as 7,700 tons of air-dropped bombs. After six days of encirclement by the German Army, the Soviet resistance ended as their troops were killed or taken prisoner. It was a devastating loss for the Soviets.

Army from a vulnerable point established during the winter counter-offensive. After a promising start, the offensive was stopped on May 15th by massive airstrikes. There were a number of critical Soviet errors by several staff officers and by Joseph Stalin, who failed to accurately estimate the 6th Army’s potential and overestimated their own newly raised forces, facilitated a German pincer attack on May 17th which cut off three Soviet field armies from the rest of the front by May 22nd. The Soviet Army was hemmed into a narrow area, and the 250,000-strong Soviet force inside the pocket was exterminated from all sides by German armored, artillery, and machine gun firepower, as well as 7,700 tons of air-dropped bombs. After six days of encirclement by the German Army, the Soviet resistance ended as their troops were killed or taken prisoner. It was a devastating loss for the Soviets.

The Counter-offensive of the Second Battle of Kharkov, was called Operation Fredericus, and was launched by the Axis forces in the region around Kharkov against the Red Army Izium bridgehead offensive, and was conducted from May 12 to May 28, 1942, on the Eastern Front during World War II. The objective was to  eliminate the Izium bridgehead over Seversky Donets, also known as the “Barvenkovo bulge,” which was one of the Soviet offensive’s staging areas. A winter counter-offensive drove German troops away from Moscow, but depleted the Red Army’s reserves. The Kharkov offensive was next Soviet attempt to expand their strategic initiative, although it failed to secure a significant element of surprise. The battle ended up being an overwhelming German victory, with 280,000 Soviet casualties compared to just 20,000 for the Germans and their allies. The German Army Group South pressed its advantage, encircling the Soviet 28th Army on June 13 in Operation Wilhelm and pushing back the 38th and 9th Armies on June 22.

eliminate the Izium bridgehead over Seversky Donets, also known as the “Barvenkovo bulge,” which was one of the Soviet offensive’s staging areas. A winter counter-offensive drove German troops away from Moscow, but depleted the Red Army’s reserves. The Kharkov offensive was next Soviet attempt to expand their strategic initiative, although it failed to secure a significant element of surprise. The battle ended up being an overwhelming German victory, with 280,000 Soviet casualties compared to just 20,000 for the Germans and their allies. The German Army Group South pressed its advantage, encircling the Soviet 28th Army on June 13 in Operation Wilhelm and pushing back the 38th and 9th Armies on June 22.

During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

Born to wealthy parents in Baltimore, Maryland in 1906, Hall was expected to marry well, and become a wife and mother, but she had other plans. Describing herself as “cantankerous and capricious, Hall set her sights on being a diplomat after studying in Paris and falling in love with France, but out of 1500 US diplomats, only 6 were women, and Hall was turned down several times. Still hoping, she took a job as a clerical worker and the US Embassy in Warsaw, Poland. Then tragically, a hunting accident on a trip to Turkey, followed by gangrene infecting the leg, caused it to require amputation, which also disqualified her from the US Foreign Service. It was a crushing blow. She decided to resign from her job and move to Paris in 1939, just as World War II was erupting.

Hall’s life took a dramatic turn on May 10, 1940, when Germany invaded France. Volunteering to drive ambulances for the French army during the six-week long Battle of France, Hall transported wounded soldiers from the front line, while dodging fire from German fighter planes overhead. With the French surrender, Hall traveled to London to support the British war effort there. As she traveled, she impressed an undercover agent who put her in touch with a senior officer in the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was Winston Churchill’s new secret service. Female operatives were not employed By the SOE, but after six months of failing to infiltrate a single new agent into France, they decided to send Hall to France as the SOE’s first female agent in the country. In the end, she would spend nearly the entire war in France, first as a spy for Britain’s SOE and later for the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Special Operations Branch.

Hall had a bit of a sense of humor, especially when it came to her heavy wooden leg, even nicknaming it Cuthbert. The leg was no obstacle to Hall’s courage either, nor her determination to defeat the Nazis, whom she bitterly hated. Hall used everything at her disposal while undercover in France, and proved herself “exceptionally adept at eluding the Gestapo as she organized resistance groups, masterminded jailbreaks for captured agents, mapped drop zones, reported on German troop movements, set up safe houses, and rescued escaped POWs and downed Allied pilots.” Like many veterans of that era, Even years after the war, Hall rarely talked about her extraordinary career. She attributes the habit to her years as a spy. She once said, “Many of my friends were killed for talking too much.”

Spy networks were amazingly able to hide in plane site, and when Hall arrived in the Vichy region of France in August 1941, it was under the cover story of being a war correspondent for the New York Post newspaper. Following her arrival in Toulouse, Hall established a resistance network called HECKLER, which gathered information about German troop movements and helped downed British pilots escape to safety. Following her work in Toulouse, she traveled to Lyon, where she helped coordinate activities of the French Resistance. Her plans changed when the United States entered the war. As a US citizen, she could be considered a traitor for working for the British spy networks, because the United States had been considered neutral. Hall was forced underground, but continued operating in France for another 14 months. A good spy needs to have a variety of disguises at the disposal, and Hall became adept at changing her appearance on a moment’s notice. She was also known by multiple aliases. She needed to be almost invisible, at least to the enemy. The Germans, at least early in the war, didn’t think that a woman was capable of being a spy. What a serious miscalculation that turned out to be!!

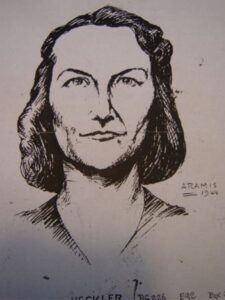

Hall’s extraordinary effectiveness amazed the SOE commanders and helped change their minds about women operating in combat zones. A year after Hall began working undercover, the SOE finally decided to send more female agents into the field. Hall’s abilities paved the way for more women to serve their countries in this important capacity. It also quickly put women spies, and Hall specifically, on the radar for the Gestapo. Soon, the hunt for “the Limping Lady” was on. They knew only her from a composite sketch, which was to her advantage. Their internal communications declared: “She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies. We must find and destroy her.” Gestapo agents…including notorious investigator Klaus Barbie, who would later be awarded the Iron Cross for torturing and executing thousands of resisters…closing in on her after the Germans seized control of Vichy France in November 1942, Hall was forced to escape to Spain.

To escape France was no easy task. It meant a three day journey on foot in heavy snow across the Pyrenees mountains. The trek was made even more challenging with an 8-pound artificial leg bound to her body with straps and a belt at the waist. At one point, she jokingly mentioned in a message to the SOE that she was concerned that “Cuthbert” would cause problems during her escape. In a funny twist, the receiver of the message didn’t recognize the nickname she used for her prosthetic. SOE headquarters responded, “If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated.” In the end, it wasn’t “Cuthbert” that caused her problems. When she arrived in Spain, she was arrested and imprisoned for illegally entering the country. Hall was an inmate for six weeks before an inmate being released was able to get word to American officials in Barcelona about her presence so they could arrange her release. She finally made it back to London in January 1943, where she was quietly made a honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire.

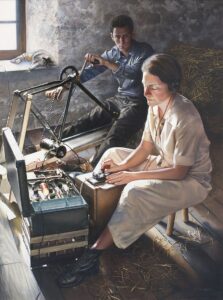

Following her imprisonment, the SOE refused to send her back to France, because they thought was too dangerous with her high profile. That decision was unacceptable to Hall, who decided to join the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was just establishing their own intelligence operation in France. The Nazi troops were everywhere by that time, so Hall took even more extreme measures to disguise herself. Among them, a French milkmaid, causing her to need to have a rather scary dentist grind down her lovely, white American teeth. In the Haute-Loire region of central France, she disguised herself as an elderly milkmaid and got to work on her radio, coordinating airdrops of arms and supplies for the resistance fighters who were blowing up bridges and sabotaging troop trains, and reporting German troop movements to Allied forces.

Her second tour in France in 1944 and 1945 was even more successful than her first, and at its peak, her network consisted of 1,500 people. With the Germans constantly attempting to track her radio signals, Hall stayed on the move, camping out in barns and attics. As D-Day approached, Hall was operating as a guerrilla leader, and she armed and trained three battalions of French resistance fighters for sabotage missions that helped paved the way for the Allied invasion. One of her many radio reports shows the breadth of her missions. She stated that her team had destroyed four bridges, derailed freight trains, severed a key rail line, and downed telephone lines. By the war’s end, Hall had spent over three full years operating undercover behind enemy lines and, in the words of an official British government report at the end of the war, she was “amazingly successful.”

After the war, when the OSS was dissolved, it became the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Hall became an intelligence analyst. For her wartime service, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France and became the only civilian woman during WWII to be awarded a Distinguished Service Cross by the US, which recognizes exceptional valor and risk of life in combat. President Harry Truman wanted to have a public ceremony for the presentation of the medal, but Hall requested a private ceremony instead, saying that she was “still operational and most anxious to get busy.” Hall worked at the CIA until she retired in 1966 and took

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

While in Haute-Loire, Hall had met and fallen in love with an OSS lieutenant, Paul Goillot, who worked for her. In 1957, the couple married after living together off-and-on for years. Hall went on to head the CIA. The other four heads were men. Hall was code named Marie and Diane, but the Germans gave her the nickname Artemis, and the Gestapo reportedly considered her “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.” Because of her artificial foot, she was also known as “the limping lady.” She died on July 8, 1982 at the age of 76 in Barnesville, Maryland.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Hitler was actually occupied for more reasons than just his birthday, as Soviet artillery had begun shelling Berlin at 11am on his 56th birthday. Preparations were being made to evacuate Hitler and his staff to Obersalzberg to make a final stand in the Bavarian mountains, but Hitler refused to leave his bunker. So, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler left the bunker for the last time. Operation Herring had begun the day before, with American aircraft dropping Italian paratroopers over Northern Italy, and with Operation Corncob came the other half of the attack, which was to remove the bridges and thereby halt the expected retreat of the German forces. I doubt if Hitler knew anything about these attacks, I’m sure his mind was on his upcoming suicide, a death which some say didn’t really take place, and a fact which we will never know for sure.

The Allied attacks of April 1945 on the Italian front, were intended to end the Italian campaign and the war in Italy, and to decisively break through the German Gothic Line, the defensive line along the Apennines and the River Po plain to the Adriatic Sea and swiftly drive north to occupy Northern Italy and get to the Austrian and Yugoslav borders as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, German strongpoints, as well as bridge, road, levee and dike blasting, and any occasional determined resistance in the Po Valley plain slowed the planned sweep down. Allied planners decided that dropping paratroops into some key areas and locales south of the River Po might help wreak havoc in the German rear area, attack German communications, and vehicle columns, further disrupting the German retreat, and prevent German engineers from blowing up key structures before Allied spearheads could exploit them. Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery, commander of the Commonwealth 8th Army, had a number of Italian paratroopers at hand for the task.

Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday with a traditional parade and full celebration, while a

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

When World War II began, Giraud was a member of the Superior War Council. He strongly disagreed with Charles de Gaulle about the tactics of using armored troops that were planned. Giraud was made the commander of the 7th Army when it was sent to the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. He was able to delay German troops at Breda on May 13th. The badly depleted 7th Army was then merged with the 9th Army. While the troops were trying to block a German attack through the Ardennes, Giraud was at the front with a reconnaissance patrol when he was captured by German troops at Wassigny on May19th. A German court-martial tried Giraud for ordering the execution of two German saboteurs wearing civilian clothes, but he was acquitted and taken to Königstein Castle near Dresden, which was used as a high-security POW prison. He would be held there for two years.

Not one to just sit around, Giraud began carefully planning his escape. He learned German and memorized a map of the area. He painstakingly made a 150 feet rope out of twine, torn bedsheets, and copper wire, which friends had smuggled into the prison for him. Using a simple code embedded in his letters home, he informed his family of his plans to escape. I doubt if they were surprised, as it would not be the first time he escaped his captors. Finally on April 17, 1942, he was ready. Königstein Castle was built on a hilltop, with steep cliff on one side. After shaving off his moustache and covering his head with a Tyrolean hat to disguise himself, Giraud lowered himself down the cliff of the mountain fortress. He discretely travelled to Schandau where he met his Special Operations Executive (SOE) contact, who provided him with a change of clothes, cash, and identity papers. Thus began the series of tactics designed to get Giraud to the Swiss border by train. By now, the border guards had been informed of his escape and were on the alert for him. Giraud walked through the mountains until he was stopped by two Swiss soldiers, who took him to Basel. Eventually, he was able to slip into Vichy France, where he was finally able to make his identity known. He tried unsuccessfully to convince Marshal Pétain that Germany would lose, and that France must resist the German occupation. His views were rejected, but at least the Vichy government refused to return Giraud to the Germans. Returning him would have been a death sentence, because Hitler had ordered Giraud’s assassination upon being caught. Giraud went to North Africa via a British submarine, and joined the French Free Forces under General Charles de Gaulle. He eventually helped to rebuild the French army.

In January 1943, Giraud took part in the Casablanca Conference along with Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D Roosevelt. Later in the same year, Giraud and de Gaulle became co-presidents of the French Committee of National Liberation, but Giraud lost support and retired in frustration in April 1944. After

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

When thinking of spies, our minds might logically think of James Bond 007 or some of the NCIS shows, but we somehow don’t think of women…at least not very often. Nevertheless, the truth is there are many women who are spies, and some of them were in the era of World War II. These women were gutsy. They faced danger defiantly. Jannetie “Hannie” Schaft was a Dutch resistance fighter during World War II. She could have done like so many others, and obediently taken the oath of loyalty to the Nazis. Her life would have gone on somewhat like it had before.

When thinking of spies, our minds might logically think of James Bond 007 or some of the NCIS shows, but we somehow don’t think of women…at least not very often. Nevertheless, the truth is there are many women who are spies, and some of them were in the era of World War II. These women were gutsy. They faced danger defiantly. Jannetie “Hannie” Schaft was a Dutch resistance fighter during World War II. She could have done like so many others, and obediently taken the oath of loyalty to the Nazis. Her life would have gone on somewhat like it had before.

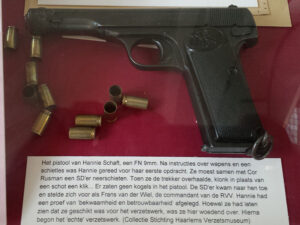

Schaft was born in Haarlem, which is the capital of the province of North Holland. Her mother was Aafje Talea Schaft (née Vrijer), who was a Mennonite woman. Her father, Pieter Schaft was attached to the Social Democratic Workers’ Party. Schaft led a sheltered life, because her parents were very protective of her following the death of her older sister. Her sheltered upbringing did not affect her personality. She was as  bold and defiant as ever. When the Nazis wanted the people to swear allegiance to them, Schaff refused to do so. Instead, she joined Raad van Verzet, a resistance group with a communist ideology. I find it hard to think about communism being considered better than socialism, but many have considered it so. In her work for Raad van Verzet, Schaft spied on soldier activity, aided refuges, and sabotaged targets. She was very capable, and feared by many. Her work gained her the reputation as “the girl with the red hair.” While it was only a nickname, it would end up being her downfall.

bold and defiant as ever. When the Nazis wanted the people to swear allegiance to them, Schaff refused to do so. Instead, she joined Raad van Verzet, a resistance group with a communist ideology. I find it hard to think about communism being considered better than socialism, but many have considered it so. In her work for Raad van Verzet, Schaft spied on soldier activity, aided refuges, and sabotaged targets. She was very capable, and feared by many. Her work gained her the reputation as “the girl with the red hair.” While it was only a nickname, it would end up being her downfall.

Having a reputation based on the color of your hair could be a good thing. All you have to do is color your hair, and you have the perfect disguise…right? Well, it did work for a time. Schaft colored her hair to cover up the red, but then she was captured by the Nazis. They had no idea who they had, but as her hair began to grow out they quickly figured it out. Once the Germans discovered that they had the legendary spy and resistance fighter in captivity, I’m sure she was brutally beaten and tortured for information. Schaft was then executed on April 17, 1945. Schaft was never a quitter and she wouldn’t quit now. Defiant to the end, she began taunting the soldier who shot her in the head, but merely grazed her. She said, “I can shoot better than that.” The second shot killed her, but not before leaving an everlasting impression on her captors and witnesses. Schaft was just 24 years old when she died. She was given a state funeral after the war, attended by Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch royal family.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When all the lifeboats were launched, and the crew and remaining passengers knew the Titanic was surely going down, Lightoller and his fellow officers “all shook hands and said ‘Good-bye’” as they saw the last lifeboat off. Lightoller then dove into the frigid water from the bridge choosing to take his chances in the water, rather than the ship. Miraculously he managed to avoid being sucked down along with the massive ship. He clung to an nearby overturned lifeboat until the survivors were rescued. Lightoller was the last person pulled aboard the Carpathia and the highest-ranking officer to survive the wreck. One might imagine that surviving the greatest  maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

Following his survival of the shipwreck of Titanic, Lightoller went on to serve as a commanding officer of the Royal Navy during World War I, Lightoller was given command of his own torpedo boat. He was decorated twice for gallantry for his actions in combat, including sinking the German submarine UB-110. He emerged from the Great War as a full naval Commander. Lightoller retired after the war, but couldn’t leave the sea behind entirely. He and his wife bought their own boat in 1929. They called it Sundower and spent the next decade cruising around northern Europe and carrying out the occasional secret surveillance mission for the Admiralty when the Germans began preparing for war again.

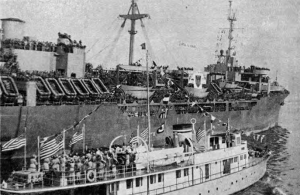

Though Lightoller was retired by the time World War II started, he provided and sailed as a volunteer on one of the “little ships” that played a part in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation. Rather than allow his motoryacht to be requisitioned by the Admiralty, he and his son Roger and a young Sea Scout named Gerald Ashcroft, crossed the English Channel in Sundowner to assist in the Dunkirk evacuation. The boat was licensed to carry just 21 passengers, but Lightoller and his crew brought back 127 servicemen. On the return journey, Lightoller evaded gunfire from enemy aircraft, using a technique described to him by his youngest son, Herbert, who had joined the RAF and been killed earlier in the war. Gerald Ashcroft later described the incident, “We attracted the attention of a Stuka dive bomber. Commander Lightoller stood up in the bow and I stood alongside the wheelhouse. Commander Lightoller kept his eye on the Stuka till the last second – then he sang out to me “Hard a port!” and I sang out to Roger and we turned very sharply. The bomb landed on our starboard side.” So, years after his first lifesaving event, Lightoller was once again saving lives in an emergency. Many people  would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

After the Second World War, Lightoller managed a small boatyard in Twickenham, West London, called Richmond Slipways, which built motor launches for the river police. Lightoller died of chronic heart disease on December 8, 1952, aged 78. He was a long-time pipe smoker, and he died during London’s Great Smog of 1952, which took the lives of many elderly people with breathing issues. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at the Commonwealth “Garden of Remembrance” at Mortlake Crematorium in Richmond, Surrey.

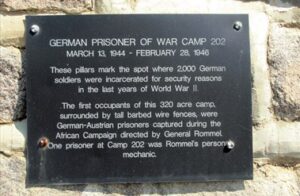

For some reason, when I think of Prisoner of War (POW) camps, I think of a place far away in a war zone, and there were some there, but as they filled up, the prisoners had to be moved to other areas. In addition to that, we needed men to work in the United States because our men were overseas fighting. The prisoners could be put to work in the fields to help grow needed foods for the country, as well as the troops. That idea was a bit foreign to me, especially when I heard that there was just such a camp that was practically in my backyard…even if I wasn’t born at the time. It’s just odd when history collides with your own neighborhood.

For some reason, when I think of Prisoner of War (POW) camps, I think of a place far away in a war zone, and there were some there, but as they filled up, the prisoners had to be moved to other areas. In addition to that, we needed men to work in the United States because our men were overseas fighting. The prisoners could be put to work in the fields to help grow needed foods for the country, as well as the troops. That idea was a bit foreign to me, especially when I heard that there was just such a camp that was practically in my backyard…even if I wasn’t born at the time. It’s just odd when history collides with your own neighborhood.

During World War II, the Greeley, Colorado POW camp had prisoners from Germany and Austria. The camp was built in 1943, and the first prisoners came in 1944. The camp was a self-contained town in itself. It had a fire station, hospital, theater, library, and classrooms. It also had electricity, water, and sewers. The prisoners who were held in the POW camps in the United States were treated well. This country wasn’t into the torture methods that the Axis of Evil nations were.

Many of the prisoners worked in the fields and paid money, for their labor, to take home with them. They were also given the chance to have fun. They had soccer teams. They dyed their t-shirts different colors using homemade dyes from vegetables. They had classes in English, German, and Mathematics. Some men were in the camp orchestra and others sang in choir. In many ways, the lives these men lived in the POW camps was better than the lives they lived at home…or at least during the war.

The Greeley POW Camp 202, was almost like a coveted assignment. It was the place the prisoners wanted to be sent. When new prisoners came to the camp, they would try to find men from their hometowns…hoping others had been as blessed as they felt to be there. The story is told that, “The old prisoners would toss out gum or paper with their names and address. One day a father and son found each other from the tossed notes.” These reunions were such a blessing for the prisoners. The guards were well liked. In fact, when one of the guards got married, the prisoners cooked their wedding night dinner for them. These good guards found favor with the prisoners.

I like to think that POW camps in and run by the United States were and are more civilized than those camps owned and run by other countries, but I don’t suppose all of them were run as compassionately as the Greeley POW Camp. We hear nightmare stories of Guantanamo Bay, and I’m sure there are others that weren’t so great. Still, I suppose things depend on the prisoners to a great degree. It is harder to show kindness to a prisoner who orchestrates a terrorist attack against our nation, killing thousands of innocent people, that it is to be compassionate to a soldier who is simply following orders, but is otherwise a kind and gentle person.

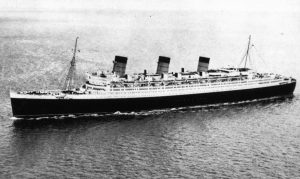

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

As ocean liners began to be built, sailing the worlds oceans suddenly went from an ordeal that was tolerated in order to improve their lives, to a way to see the world in luxury and relative speed. Emigration to the United States brought with it the need for many great ocean liners, and as they began to appear, the world became mobile. Prior to these ocean liners, it wouldn’t have been possible to really populate the new world. Europe was overcrowded, and the United States was underpopulated. Ocean liners like the Queen Mary, the Mauritania, the Lusitania, the Queen Elizabeth all made travel to the United States and even back to Europe a luxury.

During the world wars, the military commandeered these cruise ships for troop transports, and also for munitions transports. It was not always safe for these ships to be carrying civilian passengers, as was seen with the sinking of the Lusitania, so after a time the cruise ships had to stop their civilian trips and become troop transports exclusively. They had to stop, because whether the ship had munitions on it or not, it was sunk with civilian passengers onboard.

At a time when there were no passenger planes, ocean liners provided the only pathway to cross the oceans. Once war in Europe had begun, many of the great ocean liners of the period withdrew from transatlantic crossings. However, they still remained at sea. Wartime saw ocean liners converted into troopships, carrying thousands of soldiers on a single trip, from bases in the United States to bases in the theaters in Europe, Africa, and Japan. Some of the most famous names in steamship history, including Mauretania, Olympic, Leviathan,  Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Nieuw Amsterdam (II), Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth II were among those converted to troopships during times of war. These ships were a critical part of military operations. Without their support, transporting troops, equipment, and munitions would have taken far too long to do any good. These ships were the fastest ships out there at that time in history, and time was of the essence.

Of course, these ships faced the threat of submarine or airborne attack, so speed was the greatest defense the ship could have, but they couldn’t just start using the ships. These ships had to go through a process of preparation before they could be a transport ship. All of the items that were not needed for sustaining or berthing the maximum number of troops, were among the first things to go. Furniture, paintings, pianos, and everything else not needed for war would be removed and stored on land, to be returned to the ship after the war was over. The empty space was then filled with hammocks and cots for the soldiers to sleep on. They mounted guns on the decks to provide defensive capability. Of course, these liners could not act as a warship. They were just not designed for that, but a few well placed shots, might deter some of the smaller boats like U-boats from making a surface attack.

Camouflage was considered a critical part of the liners ability to survive in hostile waters. They applied “dazzle paint” to the hulls of these ocean liners. Oddly, the paint closely resembling zebra stripes!! They reasoned that alternating dark and light stripes would obscure the size, speed, heading, and type of ship when viewed from a distance. I can’t picture that exactly, and apparently it wasn’t very effective either. I guess all that it really did  was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

was to give a false sense of security to the soldiers on board.

Following the war, and ship that survived their wartime duties was restored to its former look and feel so that it could continue with its pre-war duties. Unfortunately, many of these beautiful ocean liners were lost to enemy fire during the war. Sadly, there are no real examples of these wartime liners turned troop transports, but the Queen Mary is in dry dock in Long Beach, California. Visitors can take a tour, and get a real feel for those cramped quarters. Visitors can imagine the soldiers felt as they crossed the North Atlantic, knowing that their ship was a prized target for the enemy.

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

Lieutenant Edward O’Hare, an American naval aviator of the United States Navy, was born on March 13, 1914 in Saint Louis, Missouri, to Selma Anna (Lauth) and Edward Joseph O’Hare. He was of Irish and German descent. Edward, who was nicknamed “Butch,” had two sisters, Patricia and Marilyn. Their parents divorced in 1927. Butch and his sisters stayed with their mother in Saint Louis, and their father moved to Chicago. O’Hare joined the Navy, and from there, life moved pretty fast. On July 21, 1941, O’Hare met his future wife, Rita and asked her to marry him that night. He knew immediately that she was the one. They got married on September 6, 1941 and their daughter, Kathleen was born in January or February of 1943. O’Hare first met her when she was a month old, because of missions he was on.

In the Navy, O’Hare was stationed first on the USS Saratoga, then on the USS Enterprise, and then on the USS Lexington, flying a Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat. In mid-February 1942, the Lexington sailed into the Coral Sea. A town named Rabaul, at the very tip of New Britain, one of the islands that comprised the Bismarck Archipelago, had been invaded in January by the Japanese and transformed into a stronghold. In fact, it had been turned into one huge airbase. The occupation of Rabaul put the Japanese in prime striking position for the Solomon Islands, which would have been put them in a perfect position for expanding their ever-growing Pacific empire. Given the mission of destabilizing the Japanese position on Rabaul with a bombing raid, the fighters on the Lexington took off from the aircraft carrier’s deck in a raid against the Japanese position at Rabaul. Just moments later, Lieutenant O’Hare became America’s first World War II flying ace. In the battle that took place on February 20, 1942, O’Hare believed he had shot down six bombers and damaged a seventh. Captain Frederick C Sherman later reduced that number to five, as four of the reported nine bombers were still overhead when he pulled off. Nevertheless, in the opinion of Admiral Brown and of Captain Sherman, commanding the Lexington, Lieutenant O’Hare’s actions may have saved the carrier from serious damage or even loss. In a mere four minutes, O’Hare shot down five Japanese G4M1 Betty bombers, bringing a swift end to the Japanese attack and earning O’Hare the designation “Ace,” which was given to any pilot who had five or more downed enemy planes to his credit. The attack on the bombers was great, but it ruined the element of surprise, so the mission was called off.

On the night of November 26, 1943, the USS Enterprise introduced the experiment in the co-operative control of Avengers and Hellcats for night fighting. The team consisted of three planes, breaking up a large group of land-based bombers. O’Hare volunteered to lead this mission to conduct the first-ever Navy nighttime fighter

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.