World War II

Lieutenant Thomas “Diver” Derrick was one of the 2/48th Battalion of the Australian 9th Infantry division battalion’s most decorated and beloved soldiers, serving in Australia’s most decorated unit in World War II. He was the best of the best, but it was after one event that he actually gained notoriety. Derrick was born on March 20, 1914, at the McBride Maternity Hospital in the Adelaide suburb of Medindie, South Australia, to David Derrick, a laborer from Ireland, and his Australian wife, Ada (née Whitcombe). The Derricks were poor, and Tom often walked barefoot to attend Sturt Street Public School and later Le Fevre Peninsula School. In 1928, aged fourteen, Derrick left school and found work in a bakery. By this time, he had developed a keen interest in sports, particularly cricket, Australian Rules Football, boxing and swimming; his diving in the Port River earned him the nickname of “Diver.”

Lieutenant Thomas “Diver” Derrick was one of the 2/48th Battalion of the Australian 9th Infantry division battalion’s most decorated and beloved soldiers, serving in Australia’s most decorated unit in World War II. He was the best of the best, but it was after one event that he actually gained notoriety. Derrick was born on March 20, 1914, at the McBride Maternity Hospital in the Adelaide suburb of Medindie, South Australia, to David Derrick, a laborer from Ireland, and his Australian wife, Ada (née Whitcombe). The Derricks were poor, and Tom often walked barefoot to attend Sturt Street Public School and later Le Fevre Peninsula School. In 1928, aged fourteen, Derrick left school and found work in a bakery. By this time, he had developed a keen interest in sports, particularly cricket, Australian Rules Football, boxing and swimming; his diving in the Port River earned him the nickname of “Diver.”

Derrick’s notorious accomplishment came during the Battle of Sattelberg in New Guinea in November 1943. His battalion…the 2/48th was participating in the fight. Over a period of two hours, the Australians made several attempts to clamber up the slopes to reach their objective, but each time they were repulsed by intense machine gun fire and grenade attacks. As dusk fell, it appeared impossible to reach the objective or even hold the ground already gained, and the company was ordered the men to retreat. That order brought about an unusual response in Lieutenant Derrick, who was quoted as saying, “Bugger the CO [commanding officer]. Just give me twenty more minutes and we’ll have this place. Tell him I’m pinned down and can’t get out.” With that, then Sergeant Tom Derrick hoisted the Australian Red Ensign at Sattelberg, New Guinea. He moved forward with his platoon, and Derrick attacked a Japanese post  that had been holding up the advance. He quickly destroyed the position with grenades and ordered his second section around to the right flank. The section immediately came under heavy machine gun and grenade fire from six Japanese posts, but that didn’t stop Derrick. Clambering up the cliff face under heavy fire, Derrick held on with one hand while lobbing grenades into the weapon pits with the other. Someone said he was like “a man…shooting for [a] goal at basketball.” Derrick climbed further up the cliff and in full view of the Japanese, he continued to attack the posts with grenades before following up with accurate rifle fire. True to his word, within twenty minutes, he had reached the peak and cleared seven posts…all while the demoralized Japanese defenders fled from their positions to the buildings of Sattelberg. I suppose that if the maneuver had ended differently, Derrick might have been punished for disobeying the order of his commanding officer, but as it was, how could they discipline him for such a one-man-show of prowess.

that had been holding up the advance. He quickly destroyed the position with grenades and ordered his second section around to the right flank. The section immediately came under heavy machine gun and grenade fire from six Japanese posts, but that didn’t stop Derrick. Clambering up the cliff face under heavy fire, Derrick held on with one hand while lobbing grenades into the weapon pits with the other. Someone said he was like “a man…shooting for [a] goal at basketball.” Derrick climbed further up the cliff and in full view of the Japanese, he continued to attack the posts with grenades before following up with accurate rifle fire. True to his word, within twenty minutes, he had reached the peak and cleared seven posts…all while the demoralized Japanese defenders fled from their positions to the buildings of Sattelberg. I suppose that if the maneuver had ended differently, Derrick might have been punished for disobeying the order of his commanding officer, but as it was, how could they discipline him for such a one-man-show of prowess.

Following his successful one-man-attack on the enemy, Derrick returned to his platoon, where he gathered his first and third sections in preparation for an assault on the three remaining machine gun posts in the area. While the platoon was attacking the posts, Derrick personally rushed forward on four separate occasions and threw his grenades at a range of about 8 yards, before all three were silenced. Derrick’s platoon held their position that night, before the 2/48th Battalion moved in to take Sattelberg unopposed the following morning. I’m sure that brought a level of shock to the commanding officer, who had expected a much different outcome and a much different enemy the next morning. The, then proud, battalion commander insisted that Derrick personally hoist the Australian flag over the town. It was raised at 10:00am on November 25, 1943.

The final assault on Sattelberg was later dubbed “Derrick’s Show” within the 2/48th Battalion. Derrick was already a celebrity within the 9th Division, but this action brought him to wide public attention. I suppose that could have been seen as just Derrick’s irritation over the retreat, but it also could have and was taken as disobeying an order. Derrick had advanced on multiple Japanese machine gun positions, uphill through the jungle, while under covering fire from his squadmates…and he did it by himself. In all, he cleared out 10 enemy positions, helping his unit accomplish their objective and receiving the Victoria Cross for his efforts. Unfortunately, Derrick was killed late in World War II, suffering grievous injuries at the Battle of Tarakan in May 1945.

The final assault on Sattelberg was later dubbed “Derrick’s Show” within the 2/48th Battalion. Derrick was already a celebrity within the 9th Division, but this action brought him to wide public attention. I suppose that could have been seen as just Derrick’s irritation over the retreat, but it also could have and was taken as disobeying an order. Derrick had advanced on multiple Japanese machine gun positions, uphill through the jungle, while under covering fire from his squadmates…and he did it by himself. In all, he cleared out 10 enemy positions, helping his unit accomplish their objective and receiving the Victoria Cross for his efforts. Unfortunately, Derrick was killed late in World War II, suffering grievous injuries at the Battle of Tarakan in May 1945.

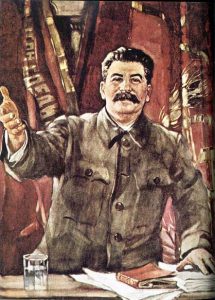

Generally speaking, a man’s word is his bond…as the saying goes, but when a man’s word can’t be trusted, well promises mean nothing, agreements mean nothing, partnership means nothing. The people who took Adolf Hitler at his word, found out the hard way, that Hitler was definitely not a man of his word. On June 22, 1941, after making an agreement, known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, Nazi Germany at Hitler’s command, launched a massive invasion against the USSR. The agreement was basically that Germany and the USSR would not attack each other. Less than two years into the agreement, Hitler broke the agreement. He was most likely planning that invasion all along, but he needed to have the people of the USSR unaware of his plans. He needed to have them trust him, so his invasion would be a complete surprise attack.

Generally speaking, a man’s word is his bond…as the saying goes, but when a man’s word can’t be trusted, well promises mean nothing, agreements mean nothing, partnership means nothing. The people who took Adolf Hitler at his word, found out the hard way, that Hitler was definitely not a man of his word. On June 22, 1941, after making an agreement, known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, Nazi Germany at Hitler’s command, launched a massive invasion against the USSR. The agreement was basically that Germany and the USSR would not attack each other. Less than two years into the agreement, Hitler broke the agreement. He was most likely planning that invasion all along, but he needed to have the people of the USSR unaware of his plans. He needed to have them trust him, so his invasion would be a complete surprise attack.

When he was ready, and aided by his far superior air force, Hitler sent his German army racing across the Russian plains. The German Army was given carte blanche in the invasion, and so they went about inflicting terrible casualties on the Red Army and the Soviet civilians. Of course, the German Army wasn’t alone in their attack. Their first targets of attack were Leningrad and Moscow. With the assistance of troops from their Axis allies, the Germans conquered the vast territory, and by mid-October the great Russian cities of Leningrad and Moscow were under siege. The Soviets held on, and the coming winter forced the German offensive to pause.

Hitler set his sights on the summer of 1942, and ordered the Sixth Army, under General Friedrich Paulus, to take Stalingrad in the south. Stalingrad was an industrial center and therefore, an obstacle to Nazi control of the precious Caucasus oil wells. The oil wells were a crucial part of the control process. The Army made advances across the Volga River in August, while the German Fourth Air Fleet reduced Stalingrad to burning rubble, killing more than 40,000 civilians. With the first attack behind them, Paulus ordered the first offensives into Stalingrad in September, estimating that it would take his army about 10 days to capture the city.

The ensuing battle was one of the most horrific battles of World War II. It was also quite likely the most important because it was the turning point in the war between Germany and the USSR. The USSR’s Red Army was furious and had an ax to grind over the ruined city and their lost loved ones and friends. Now, the German Sixth Army faced General Vasily Chuikov leading a bitter Red Army seeking revenge. They quickly transformed destroyed buildings and rubble into natural counter offensive fortifications. Then, using a method of fighting known as the Rattenkrieg or “Rat’s War,” the opposing forces broke into squads eight or 10 strong and fought each other for every house and yard of territory. The battle saw rapid advances in street-fighting technology. Things like a German machine gun that shot around corners and a light Russian plane that glided silently over German positions at night, dropping bombs without warning were birthed during this battle. The biggest problem the armies faced, however, was a lack of necessary food, water, or medical supplies, causing tens of thousands of soldiers to die every week.

The biggest miscalculation Hitler made was the resolve of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who was determined to liberate the city named after him. In November he ordered massive reinforcements to the area. On November 19, General Zhukov launched a great Soviet counteroffensive. German command underestimated the scale of the counterattack, and the Sixth Army was quickly overwhelmed by the offensive, which involved 500,000 Soviet troops, 900 tanks, and 1,400 aircraft. Within three days, the entire German force of more than 200,000 men was encircled. Before long, the Italian and Romanian troops at Stalingrad surrendered. That didn’t follow for the Germans, who hung on. Of course, Hitler would not let them surrender, so they waited…receiving limited supplies by air and waiting for reinforcements. Hitler ordered Paulus to remain in place and promoted him to field marshal, because no Nazi field marshal had ever surrendered.

The Germans lost as many lives to starvation and the bitter Russian winter, as they did to the merciless Soviet troops. Their supply line was completely cut off on January 21, 1943, when the last of the airports held by the Germans fell to the Soviets…completely cutting off their supplies. Despite Hitler’s threats, Paulus surrendered German forces in the southern sector on January 31, and on February 2 the remaining German troops surrendered. By the time Paulus surrendered, there were only 90,000 German soldiers still alive. They may

have thought they were among the lucky ones, but of the 90,000, only 5,000 survived the Soviet prisoner-of-war camps and make it back to Germany.

have thought they were among the lucky ones, but of the 90,000, only 5,000 survived the Soviet prisoner-of-war camps and make it back to Germany.

The Battle of Stalingrad was the turning point in the war between Germany and the Soviet Union. Chuikov had played such an important role in the victory. Later, it was he who led the Soviet drive on Berlin. As a reward, on May 1, 1945, he was given the right to personally accept the German surrender of Berlin. Paulus, who felt betrayed by Hitler, was among the German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. He provided testimony at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in 1946. After his release by the Soviets in 1953, he settled in East Germany.

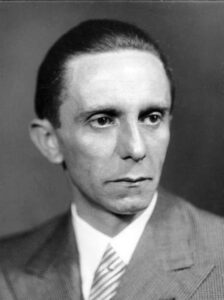

When the Nazis were trying to take over the world, one tool they felt was vital to their effort was the radio, or rather the control over the radio. If the Nazis could control the news people heard, they believed they could stop any resistance from the people, especially good people who didn’t want to be involved in the evil that Hitler was trying to carry out. The only way to control the situation was with the Nazi propaganda over controlled airwaves. The propaganda effort was a relatively new technology that the Nazis very likely pioneered.

When the Nazis were trying to take over the world, one tool they felt was vital to their effort was the radio, or rather the control over the radio. If the Nazis could control the news people heard, they believed they could stop any resistance from the people, especially good people who didn’t want to be involved in the evil that Hitler was trying to carry out. The only way to control the situation was with the Nazi propaganda over controlled airwaves. The propaganda effort was a relatively new technology that the Nazis very likely pioneered.

When the Germans first started their propaganda broadcasts, they were in both German and English. It was thought, by German propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, that since the United States had not entered the war, maybe they were still able to be turned toward German thinking. Within a few months of the breakout of World War II, German propagandists were transmitting no less than eleven hours of programming a day. In the first year of Nazi propaganda programming, broadcasters attempted to destroy pro-British feeling rather than arouse pro-German sentiment. I would assume that they were attempting to look like the innocent victim, and not the evil aggressor. These propagandists targeted certain groups, including capitalists, Jews, and selected newspapers/politicians. Doesn’t this sound like the media of today? By the summer of 1940, the Nazis, realizing that the United States would never be on their side, had abandoned all attempts to win American sympathy. The tone of German radio broadcasts quickly became critical towards the United States.

Goebbels, claimed the radio was the “eighth great power” and he, along with the Nazi party, recognized the power of the radio in the propaganda machine of Nazi Germany. Goebbels, recognizing the importance of radio in disseminating the Nazi message, quickly approved a mandate whereby millions of cheap radio sets were subsidized by the government and distributed to the German citizens. It reminds me of the “free cellphone”

program of Barack Obama. It was Goebbels’ job to propagate the anti-Bolshevik statements of Hitler and aim them directly at neighboring countries with German-speaking minorities. In Goebbels’ “Radio as the Eighth Great Power” speech, he proclaimed, “It would not have been possible for us to take power or to use it in the ways we have without the radio…It is no exaggeration to say that the German revolution, at least in the form it took, would have been impossible without the airplane and the radio…[Radio] reached the entire nation, regardless of class, standing, or religion. That was primarily the result of the tight centralization, the strong reporting, and the up-to-date nature of the German radio.”

program of Barack Obama. It was Goebbels’ job to propagate the anti-Bolshevik statements of Hitler and aim them directly at neighboring countries with German-speaking minorities. In Goebbels’ “Radio as the Eighth Great Power” speech, he proclaimed, “It would not have been possible for us to take power or to use it in the ways we have without the radio…It is no exaggeration to say that the German revolution, at least in the form it took, would have been impossible without the airplane and the radio…[Radio] reached the entire nation, regardless of class, standing, or religion. That was primarily the result of the tight centralization, the strong reporting, and the up-to-date nature of the German radio.”

The Nazi regime began to use the radio to deliver its message to both occupied territories and enemy states, as well as domestic broadcasts. One of the main targets was the United Kingdom to which William Joyce broadcast regularly, gaining him the nickname “Lord Haw-Haw” in the process. Broadcasts were also made to the United States, notably through Robert Henry Best and Mildred ‘Axis Sally’ Gillars. As a normal practice of the Propaganda Minister’s office, the radio, just like the newspapers fell under strict German supervision during the occupation. In January 1941, Dutch stations were replaced by a single state-run broadcaster overseen by the NSB (Dutch Nazi Party). This station primarily transmitted pro-German programs.

The Dutch were not easily fooled, however. So, for news from the Allied camp the Dutch secretly listened to the BBC and Radio Oranje, the Dutch government’s radio station in exile, transmitting from London. One might wonder how that was possible, given the controls in place at the time, but people hardly paid attention to the

listening ban imposed by the Germans. The occupying German forces tried to jam the reception of Radio Free Orange and the BBC, but with a handy device, easily made at home, the Dutch people were able to listen to broadcasts from London very little interference. It was therefore referred to as a moffenzeef (‘Kraut filter’) or ‘German filter’ because it sifted out jamming signals. The device was of monumental significance, because it kept the people from being effectively brainwashed by rogue media forms that were controlled by an evil government. The Kraut Filter might just have been the single greatest “non-weapon” of the war.

listening ban imposed by the Germans. The occupying German forces tried to jam the reception of Radio Free Orange and the BBC, but with a handy device, easily made at home, the Dutch people were able to listen to broadcasts from London very little interference. It was therefore referred to as a moffenzeef (‘Kraut filter’) or ‘German filter’ because it sifted out jamming signals. The device was of monumental significance, because it kept the people from being effectively brainwashed by rogue media forms that were controlled by an evil government. The Kraut Filter might just have been the single greatest “non-weapon” of the war.

In 1913, Milunka Savic joined the Serbian army in her brother’s place, cutting her hair and donning men’s clothes. You might wonder why she would do such a thing, and why her brother didn’t go and do his duty. This story isn’t about her heroics in the face of her brother’s cowardice, but rather her heroics when her brother truly could not serve. In 1912, Milunka’s brother received call-up papers for mobilization for the First Balkan War, but at the time, he was quite ill with tuberculosis. Milunka could have just told the authorities that he was ill, and he would have been excused, but she knew that the war effort was important, so she chose to go in his place. She started her transformation by cutting her hair and started wearing men’s clothes, then she joined the Serbian army. She saw combat almost immediately, and while many women of that era would have turned tail and run, she did not. She received her first medal and was promoted to corporal in the Battle of Bregalnica. While she was engaged in battle, Milunka was wounded, and as she was being treated in the hospital, her true gender was discovered by some very surprised physicians. I suppose you could say that she hadn’t thought this part of the plan out very well, or maybe she just didn’t plan to be wounded!! Nevertheless, here she was, and she had a problem.

In 1913, Milunka Savic joined the Serbian army in her brother’s place, cutting her hair and donning men’s clothes. You might wonder why she would do such a thing, and why her brother didn’t go and do his duty. This story isn’t about her heroics in the face of her brother’s cowardice, but rather her heroics when her brother truly could not serve. In 1912, Milunka’s brother received call-up papers for mobilization for the First Balkan War, but at the time, he was quite ill with tuberculosis. Milunka could have just told the authorities that he was ill, and he would have been excused, but she knew that the war effort was important, so she chose to go in his place. She started her transformation by cutting her hair and started wearing men’s clothes, then she joined the Serbian army. She saw combat almost immediately, and while many women of that era would have turned tail and run, she did not. She received her first medal and was promoted to corporal in the Battle of Bregalnica. While she was engaged in battle, Milunka was wounded, and as she was being treated in the hospital, her true gender was discovered by some very surprised physicians. I suppose you could say that she hadn’t thought this part of the plan out very well, or maybe she just didn’t plan to be wounded!! Nevertheless, here she was, and she had a problem.

She could have been in a lot of trouble at this point, but she had proven to such a competent soldier, her commanding officers were hesitant to punish her. It was decided that they would send her to a nursing division, but Milunka informed them that she would serve her country only in combat. This had to be an amazing woman, who was far ahead of her time in the area of women in combat. While they could have insisted, I suppose they would have also lost not only a nurse, but a great soldier, so they relented, and she went back to her unit. Milunka went on to fight in three wars and earn seven medals, including the Croix de Guerre and the British medal of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael. It is believed that she may in fact be the most-decorated female combatant not only in Serbia, but in the entire history of warfare. To me, Milunka Savic was not just a hero for her fighting efforts, but for stepping up when her brother could not. I’m sure he is quite proud of his sister.

She was demobilized in 1919, and turned down an offer to move to France, where she was eligible to collect a comfortable French army pension. Milunka found work as a postal worker in Belgrade. In 1923, she married Veljko Gligorijevic, whom she met in Mostar, and divorced immediately after the birth of their daughter Milena. She loved children and went on to adopt three other daughters. In the interwar period, Milunka was largely forgotten by the general public. Life was not easy for her. She worked several menial jobs up to 1927, after which she had steady employment as a cleaning lady in the State Mortgage Bank. Eight years later, she was promoted to cleaning the offices of the general manager…such menial labor for a hero.

During the German occupation of Serbia in World War II, Milunka refused to attend a banquet organized by Milan Nedic, which was to be attended by German generals and officers. She was arrested and taken to Banjica concentration camp, where she was imprisoned for ten months. By the late 1950s, her daughter became ill, and before long she found herself living in poverty. In 1972, public pressure and a newspaper article highlighting her difficult housing and financial situation led to her finally receiving the recognition she deserved. She was given a small apartment by the Belgrade City Assembly. She died in Belgrade on October 5, 1973, at the age of 85, and was buried in Belgrade New Cemetery.

Before the summer of 1971, a person had to be 21 years old in order to vote. That was before the 26 Amendment was signed into law, on July 5, 1971, by President Richard Nixon. The amendment had passed through the Senate, House, and states in record time, lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, but it was not a quick victory. The battle was hard-fought, mostly by young people between the ages of 18 and 21, who were eligible to be drafted, but didn’t have the right to vote. The battle had raged since World War II.

Before the summer of 1971, a person had to be 21 years old in order to vote. That was before the 26 Amendment was signed into law, on July 5, 1971, by President Richard Nixon. The amendment had passed through the Senate, House, and states in record time, lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, but it was not a quick victory. The battle was hard-fought, mostly by young people between the ages of 18 and 21, who were eligible to be drafted, but didn’t have the right to vote. The battle had raged since World War II.

When the United States joined in the World War II war effort, it didn’t take long to find that they were going to need more men. It wasn’t that so many were killed, although that certainly was a problem too, but less than a year in, President Roosevelt and his administration faced a serious dilemma. They had 20 million eligible men who were registered for the draft, but 50% of them were rejected either for health reasons or because they were deemed illiterate. The United States had to have more men, and there was only one place to get them…expand the eligible draft ages. So, on November 11, 1942, Congress approved lowering the minimum draft age to 18 and raising the maximum to 37. Soon after, the slogan “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote” was born. For the over 21 draftees, the right to vote was already theirs, but the 18 to 20 year olds did not, and they felt like if they could be asked to fight and die, they should be able to vote…like ither adults, and much like the fight we have today with “old enough to fight, old enough to drink.” I’m not sure the current protestors will win their battle, however.

The changing of the voting age didn’t come easy either. Many people thought that 18-year-olds were just too young to understand politics. West Virginia congressman Jennings Randolph became the first supporter for lowering the age. In 1942, he introduced the first of 11 bills he sponsored over his tenure in Congress. Despite support from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and a number of senators and representatives, Congress failed to pass any legislation. Nevertheless, a popular movement was growing. Finally, in 1943, Georgia became the first  state to lower the voting age for state and local elections to 18, with Kentucky following suit in 1955. It broke the ice. While these young voters couldn’t vote for US offices, they had a say in their own state. The movement to lower the voting age began to gain grassroots traction when newly elected President Dwight D Eisenhower expressed his support in his 1954 State of the Union address, “For years our citizens between the ages of 18 and 20 have, in time of peril, been summoned to fight for America. They should participate in the political process that produces this fateful summons. I urge Congress to propose to the States a constitutional amendment permitting citizens to vote when they reach the age of 18.”

state to lower the voting age for state and local elections to 18, with Kentucky following suit in 1955. It broke the ice. While these young voters couldn’t vote for US offices, they had a say in their own state. The movement to lower the voting age began to gain grassroots traction when newly elected President Dwight D Eisenhower expressed his support in his 1954 State of the Union address, “For years our citizens between the ages of 18 and 20 have, in time of peril, been summoned to fight for America. They should participate in the political process that produces this fateful summons. I urge Congress to propose to the States a constitutional amendment permitting citizens to vote when they reach the age of 18.”

While it was gaining momentum, it was still slow-going. It would not be until much of the American public became disillusioned by the lengthy and costly war in Vietnam in the mid 1960s that the movement to lower the voting age gained widespread public support. “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote” found its way back into the American consciousness in the form of protest signs and chants. The push was revived, and then-Senator Randolph and other politicians continued to push legislation to lower the age to 18, including passing an amendment into 1965’s Voting Rights Act in 1970 that applied lowering the age to federal, state, and local elections. As the amendment was being signed into law, President Nixon thought it might be problematic. He issued a public statement that the federal government regulating state and local elections was likely to be “deemed unconstitutional and that only an amendment would secure this right.” He was right, and the amendment was struck down in the 1970 Supreme Court case Oregon v. Mitchell, ruling that the federal government could not make mandates for state and local elections. That meant that the fight continued. The initial result was a mixed system in which state and local elections had different rules than federal elections. That brought with it logistical problems on election days in states across the country, bringing more protests and lobbying efforts. The biggest problem was the 18 to 20 year olds worrying that their draft numbers were being called despite having no say in electing their representation. “Project 18” continued to put the pressure on legislators to take action. Marches were held all over the nation.

Finally, their hard work paid off. On March 10, 1971, the Senate voted unanimously in favor of a Constitutional amendment lowering the voting age to 18, followed by an overwhelming majority of the House voting in favor on March 23, 1971. The states quickly ratified the amendment, and it took effect on July 1, 1971, nearly 30 years after Senator Randolph first proposed lowering the voting age. In response to its passing, the senator remarked, “I believe that our young people possess a great social conscience, are perplexed by the injustices which exist in the world and are anxious to rectify these ills.” Finally, those who were “old enough to fight” could also vote.

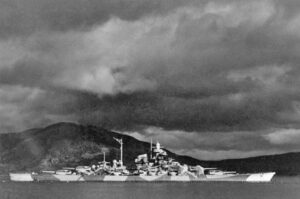

While many people have heard about the sinking of the German ship, The Bismarck, many may not have known that the Bismarck had a sister ship called the Tirpitz. Both ships were quite likely the same level of severity of threat to the war effort, but the Tirpitz somehow didn’t stand out as much…possibly because of the song that was written called “Sink the Bismarck” by Johnny Horton, and the fact that the Bismarck sank the Royal Navy battleship, HMS Hood, and that was the sinking than was the first and last straw before the Bismarck was taken down.

While many people have heard about the sinking of the German ship, The Bismarck, many may not have known that the Bismarck had a sister ship called the Tirpitz. Both ships were quite likely the same level of severity of threat to the war effort, but the Tirpitz somehow didn’t stand out as much…possibly because of the song that was written called “Sink the Bismarck” by Johnny Horton, and the fact that the Bismarck sank the Royal Navy battleship, HMS Hood, and that was the sinking than was the first and last straw before the Bismarck was taken down.

Nevertheless, the Tirpitz, commissioned in 1941, posed a grave threat to Allied shipping too. The Tirpitz was the German Navy’s mighty 42,900-ton battleship that carried a main armament of eight 15-inch guns. The ship saw limited action, however, spending most of its war career in Norwegian waters where it posed a constant danger to Allied convoys that were bound for Russia. Because the ship was in those waters, the Allies were forced to maintain a large fleet in northern waters to guard against the Tirpitz and repeated attempts were made by both the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy to sink the menacing ship. During the short life of the Bismarck, the battleship sank one ship…HMS Hood, and then the Royal Navy took the ship down. The Tirpitz was a menace a bit longer, but it never actually sank a ship. It took part in a number of battles, mostly shoot at other ships, but sinking none. Still, the possibility was always there that the Tirpitz could take out ships belonging to the Allies.

The Royal Air Force tried to take out the Tirpitz before it even set sail, by bombing it in January of 1941 while it  was being completed in a Wilhelmshaven dry dock. Somehow, the bombs actually “straddled” the battleship, missing it, and doing very little damage. Tirpitz was attacked again later in 1941 by twin engined bombers and in April 1942, when it was located and attacked by Halifaxes and Lancasters. Unfortunately, no bombs found their target that time either. The Royal Navy also attempted to take down the ship on a number of occasions with miniature submarines and carrier-based aircraft. Those attacks hit their mark, but had little effect, because Tirpitz had a double layer of armor plating. Finally, British inventor, Sir Barnes Wallis, built a special bomb for the job. He had previously developed the bouncing bomb used in the Dambusters Raid, so his inventions were trusted. In 1944 he devised the “Tallboy,” a 12,030-pound weapon capable of piercing the Tirpitz’s armor plating.

was being completed in a Wilhelmshaven dry dock. Somehow, the bombs actually “straddled” the battleship, missing it, and doing very little damage. Tirpitz was attacked again later in 1941 by twin engined bombers and in April 1942, when it was located and attacked by Halifaxes and Lancasters. Unfortunately, no bombs found their target that time either. The Royal Navy also attempted to take down the ship on a number of occasions with miniature submarines and carrier-based aircraft. Those attacks hit their mark, but had little effect, because Tirpitz had a double layer of armor plating. Finally, British inventor, Sir Barnes Wallis, built a special bomb for the job. He had previously developed the bouncing bomb used in the Dambusters Raid, so his inventions were trusted. In 1944 he devised the “Tallboy,” a 12,030-pound weapon capable of piercing the Tirpitz’s armor plating.

The ship was doomed, and on November 12, 1944, thirty Lancasters took off from Scotland flying in clear weather flew at 1,000 feet to avoid early detection by enemy radar prior to rendezvousing at a lake 100 miles southeast of Tromso. The attacking force then climbed to bombing height of between 12,000 and 16,000 feet. The Tirpitz was sighted from about 20 miles away. The crew called for air cover…frantically, but no cover came. They were sitting ducks when the Lancasters passed over the last mountain and the fjord with the Tirpitz came into view. When the bombers were about 13 miles away, the Tirpitz began firing their anti-aircraft guns. They  were joined by shore batteries and two flak ships. It was not enough. The Lancasters released their bombs were released and waited thirty long seconds for the results. The first bombs narrowly missed the target, but then a great yellow flash burst on the foredeck and the Tirpitz was seen to tremble as it was hit by at least two Tallboys. Smoke shot up to about 300 feet and the ship had started to list badly. Then a tremendous explosion was heard as the ammunition stores magazine went up. The ship rolled over to port and capsized. After 10 minutes only the hull visible from the air. Approximately 1000 of her crew were killed. The attacking aircraft, all with only minimal damaged returned safely to base. The Tirpitz was gone…finally.

were joined by shore batteries and two flak ships. It was not enough. The Lancasters released their bombs were released and waited thirty long seconds for the results. The first bombs narrowly missed the target, but then a great yellow flash burst on the foredeck and the Tirpitz was seen to tremble as it was hit by at least two Tallboys. Smoke shot up to about 300 feet and the ship had started to list badly. Then a tremendous explosion was heard as the ammunition stores magazine went up. The ship rolled over to port and capsized. After 10 minutes only the hull visible from the air. Approximately 1000 of her crew were killed. The attacking aircraft, all with only minimal damaged returned safely to base. The Tirpitz was gone…finally.

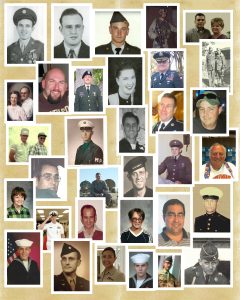

Veteran’s Day is a day about sacrifice and honor, duty and dedication, war and peace, but the day cannot pass for me without thoughts of my dad, and how much I miss him. I know I am not alone in these thoughts, because my sisters also miss him, as well as the rest of our family. My dad Staff Sergeant Allen L Spencer, fought in World War II, serving as flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber. Dad came home after his successful service, which is why my sisters and I are alive, and why he was a veteran. A veteran is someone who served in the military and came home after.

Veteran’s Day is a day about sacrifice and honor, duty and dedication, war and peace, but the day cannot pass for me without thoughts of my dad, and how much I miss him. I know I am not alone in these thoughts, because my sisters also miss him, as well as the rest of our family. My dad Staff Sergeant Allen L Spencer, fought in World War II, serving as flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber. Dad came home after his successful service, which is why my sisters and I are alive, and why he was a veteran. A veteran is someone who served in the military and came home after.

Soldiers really are a rare bread, created by God to go out and protect those who cannot protect themselves, even when those they protect don’t know or even care that it is a soldier who has watched over them, their borders, and their homes. The sacrifice a veteran gave was not about dying, although they will do that if it is what is required of them. The sacrifice of a veteran is being away from their family and friends. Some veterans miss out on their babies being born, their wedding anniversaries, weddings of family members, and so much more. They don’t know most of, if any of the people they are protecting, but they go anyway, because they are needed. Lives depend on their loyalty.

These men and women deserve our respect and that is what today is all about. It is a day to remind our veterans that we are grateful for their service, and happy that they were able to return to us and to their family members. War is a horrible thing, and no one really wants to be so far away from home fighting in a war they didn’t start, and one they wish hadn’t ever taken place. Unfortunately, evil exists in our world, and because it does, soldiers are a vital part of our security. God knew that soldiers would have to be people of honor and dedication, with a strong sense of duty and love for their fellow man. They would have to be people of courage and bravery…able to bite back the fear that dwells all around them. God knew the kind of people they would have to be…heroes. And that is what every veteran is, was, and always will be…a hero. Today is Veteran’s Day. It is a day to honor those who have given so much to keep us free. Thank you all for your great service. God bless you…every one of you.

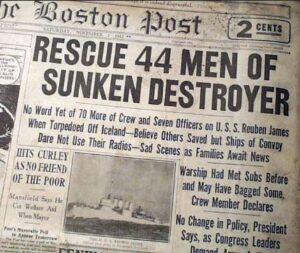

It is common practice in the military to name destroyers (DD) and destroyer Escorts (DE) after Navy and Marine Corps heroes. The USS Reuben James (DD-245) was a four-funnel (four stack) Clemson-class destroyer made after World War I, and it was the first of three US Navy ships named for Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James (1776–1838), who distinguished himself fighting in the First Barbary War. Apparently, on August 3, 1804, James put himself between his commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and the sword of a Tripolitan sailor, who was trying to defend his commander. When James stepped between the descending sword and his commander, he took the blow to his head. Amazingly, the blow did not kill him, and he recovered later to continue serving in the Navy.

It is common practice in the military to name destroyers (DD) and destroyer Escorts (DE) after Navy and Marine Corps heroes. The USS Reuben James (DD-245) was a four-funnel (four stack) Clemson-class destroyer made after World War I, and it was the first of three US Navy ships named for Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James (1776–1838), who distinguished himself fighting in the First Barbary War. Apparently, on August 3, 1804, James put himself between his commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and the sword of a Tripolitan sailor, who was trying to defend his commander. When James stepped between the descending sword and his commander, he took the blow to his head. Amazingly, the blow did not kill him, and he recovered later to continue serving in the Navy.

The Destroyer named after Boatswain’s Mate Reuben James, was the first sunk by hostile action in the European Theater of World War II. The USS Reuben James was laid down on April 2, 1919, by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation of Camden, New Jersey, launched on October 4, 1919, and commissioned on September 24, 1920. the ship was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. Mainly, it was being used in the Mediterranean Sea during 1921–1922. The ship went from Newport, Rhode Island, on November 30, 1920, to Zelenika, Yugoslavia and arrived on December 18th. It operated in the Adriatic Sea and the Mediterranean out of Zelenika and Gruz (Dubrovnik), Yugoslavia, assisting refugees and participating in post-World War I investigations during the spring and summer of 1921. Then, it joined the protected cruiser Olympia at ceremonies marking the return of the Unknown Soldier to the United States in October 1921 at Le Havre. From October 29, 1921, to February 3, 1922, it assisted the American Relief Administration in its efforts to relieve hunger and misery at Danzig. After completing its tour of duty in the Mediterranean, it departed Gibraltar on July 17th.

Following its tour in the Mediterranean, the ship was based out of New York City, where it routinely patrolled the Nicaraguan coast to prevent the delivery of weapons to revolutionaries in early 1926. During the spring of 1929, it participated in fleet maneuvers that helped develop naval airpower. On January 20, 1931, the Reuben James was

decommissioned at Philadelphia, only to be recommissioned on March 9, 1932. The ship again operated in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, patrolling Cuban waters during the coup by Fulgencio Batista. Then, in 1934, it was transferred to San Diego. After maneuvers that evaluated aircraft carriers, the Reuben James returned to the Atlantic Fleet in January 1939.

Upon the beginning of World War II in Europe in September 1939, but before the United States joined in the fight, the Reuben James was assigned to the Neutrality Patrol, guarding the Atlantic and Caribbean approaches to the American coast. The ship joined the force established to escort convoys sailing to Great Britain in March 1941. With U-Boat attacks on the rise, this force began escorting convoys as far as Iceland, after which the convoys became the responsibility of British escorts. At that time, it was based at Hvalfjordur, Iceland, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Heywood Lane Edwards.

It would be the escort post that would be the ship in the wrong place at the wrong time. On October 23rd, it sailed from Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland, with four other destroyers, escorting eastbound Convoy HX 156. All seemed to be going well until, at dawn on October 31st, the Reuben James was torpedoed near Iceland by German U-Boat U-552 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Erich Topp. The Reuben James had positioned itself between an ammunition ship in the convoy and the known position of a German “wolfpack.” The “wolfpack” was a group of submarines poised to attack the convoy. Apparently, the destroyer was not flying the Ensign of the United States, that might have saved it…or maybe not, since it was in the process of dropping depth charges on another U-boat when U-552 engaged. The Reuben James was hit forward by a torpedo meant for a merchant ship and the torpedo blew the entire bow off when a magazine exploded upon the torpedoes impact. The bow of the Reuban James sank immediately. The aft section floated for five minutes before going down. I can only

imagine the shock of those around them when the ship was gone so quickly. USS Reuben James carried a crew of seven officers and 136 enlisted men. They also had one enlisted passenger. Of the total of 144 men on board, 100 were killed, including all the officers. Only 44 enlisted men survived the attack. It was the first US warship sunk in World War II, and strangely, the destroyer was sunk before the United States had officially joined the war.

imagine the shock of those around them when the ship was gone so quickly. USS Reuben James carried a crew of seven officers and 136 enlisted men. They also had one enlisted passenger. Of the total of 144 men on board, 100 were killed, including all the officers. Only 44 enlisted men survived the attack. It was the first US warship sunk in World War II, and strangely, the destroyer was sunk before the United States had officially joined the war.

A number of years ago, I had the opportunity to go on a couple of business trips with my boss, Jim Stengel, in his plane. At that time, he introduced me to aviation charts, and I found them very interesting. You could see every airport on them, even the small private airports. You could also see every river, lake, and even pond, and they actually looked right on the map. I suppose the shapes would be off these days, due to droughts and such, but with GPS, I suppose they aren’t as necessary. Aviation charts could almost be considered a novelty now.

A number of years ago, I had the opportunity to go on a couple of business trips with my boss, Jim Stengel, in his plane. At that time, he introduced me to aviation charts, and I found them very interesting. You could see every airport on them, even the small private airports. You could also see every river, lake, and even pond, and they actually looked right on the map. I suppose the shapes would be off these days, due to droughts and such, but with GPS, I suppose they aren’t as necessary. Aviation charts could almost be considered a novelty now.

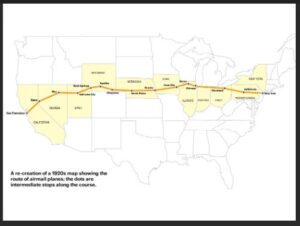

These days airmail is common, but on August 20, 1920, when the United States opened its first coast-to-coast airmail delivery route, we were just 60 years past the time when the Pony Express closed up shop. To me that is astounding…from horses to airplanes in just 60 years. When airmail got started, they didn’t have any of those aviation charts that had fascinated me on those flights with Jim. In those days, pilots had to navigate by sight…yikes!! Just imagine flying in bad weather, not to mention night flying, which was just about impossible. Some brainstorming was needed.

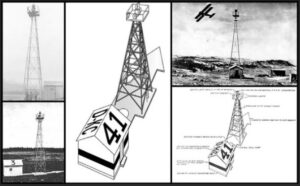

The Postal Service came up with a unique navigational system. The world’s first ground-based civilian navigation system was made up of a series of lighted beacons that extended from New York to San Francisco. I would think the pilots would have to be quite experienced to follow this plan. The plan included a series of 70-foot concrete arrows, placed ten miles apart from coast to coast. The arrows were painted bright yellow, and at the center of each arrow, stood a 51-foot steel tower. On top of the tower was a million-candlepower rotating beacon. Below the rotating light were two course lights pointing forward and backward along the arrow. The course lights flashed a code to identify the beacon’s number. A generator shed at the tail, or feather end of each arrow powered the beacon and lights, if that became necessary.

Like the railroad, the Airmail system was built in stages. By 1924, just a year after Congress funded it, the line of giant concrete markers stretched from Rock Springs, Wyoming to Cleveland, Ohio. The next summer, it reached all the way to New York and then, by 1929, it extended all the way to San Francisco. It worked so well, that in 1926, the new Aeronautics Branch in the Department of Commerce, now known as United States Postal Service, proposed a 650-mile air mail route linking Los Angeles to Salt Lake City. That route was designated as Contract Air Mail Route 4 (CAM-4). The system seemed well on its way to modernizing mail delivery forever, but

before long, the advances in communication and navigation technology made the big arrows obsolete, as new technology will. By the 1940s, the Commerce Department decommissioned the beacons. To help the war effort, the steel towers were torn down and sent to be used elsewhere. Today, many of the arrows have been removed, but there are still a few that remain. I suppose if you spent some time scanning Google Earth, or flying along the old routes, you might be able to see a few of these old pieces of history.

before long, the advances in communication and navigation technology made the big arrows obsolete, as new technology will. By the 1940s, the Commerce Department decommissioned the beacons. To help the war effort, the steel towers were torn down and sent to be used elsewhere. Today, many of the arrows have been removed, but there are still a few that remain. I suppose if you spent some time scanning Google Earth, or flying along the old routes, you might be able to see a few of these old pieces of history.

In a very different time in America, being a communist was not accepted, and it really shouldn’t be accepted now, but that is not the opinion of every person in the United States today. Nevertheless, on October 20, 1947, saw the beginning of the notorious Red Scare. At that time, a Congressional committee began investigating the Communist influence that was, or at least was suspected of infiltrating one of the world’s richest and most glamorous communities…Hollywood, California.

In a very different time in America, being a communist was not accepted, and it really shouldn’t be accepted now, but that is not the opinion of every person in the United States today. Nevertheless, on October 20, 1947, saw the beginning of the notorious Red Scare. At that time, a Congressional committee began investigating the Communist influence that was, or at least was suspected of infiltrating one of the world’s richest and most glamorous communities…Hollywood, California.

One of the greatest fears after World War II, was that the Cold War began to heat up between the United States and the communist-controlled Soviet Union. Conservatives in Washington were working hard to remove any communists in government. Then, they set their sights on those people who were alleged “Reds” in the liberal movie industry. During the investigation that began in October 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) questioned a number of prominent people. During the interviews, the committee asked point-blank, “Are you or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”

It might have been fear or maybe a sense of patriotism, but some witnesses, including director Elia Kazan,  actors Gary Cooper and Robert Taylor, and studio honchos Walt Disney and Jack Warner, all gave the committee names of colleagues they had suspected of being communists. That began a more grueling interrogation of a small group known as the “Hollywood Ten.” All of the “Hollywood Ten” resisted the accusations, complaining that the hearings were illegal and violated their First Amendment rights. The 10 were Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr, John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo. While they weren’t convicted of being communist, they were all convicted of obstructing the investigation and each served jail terms.

actors Gary Cooper and Robert Taylor, and studio honchos Walt Disney and Jack Warner, all gave the committee names of colleagues they had suspected of being communists. That began a more grueling interrogation of a small group known as the “Hollywood Ten.” All of the “Hollywood Ten” resisted the accusations, complaining that the hearings were illegal and violated their First Amendment rights. The 10 were Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr, John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo. While they weren’t convicted of being communist, they were all convicted of obstructing the investigation and each served jail terms.

The Hollywood establishment, after being pressured by Congress, started a blacklist policy. The blacklist involved the practice of denying employment to entertainment industry professionals believed to be or to have been Communists or sympathizers. Actors, screenwriters, directors, musicians, and other American entertainment professionals were barred from work by the studios. This was usually done on the basis of their membership in, or alleged membership in, or sympathy with the Communist Party USA, or their refusal to assist Congressional investigations into party activities. The policy brought about the banning the work of about 325 screenwriters, actors, and directors who had not been cleared by the committee.

Those blacklisted included composer Aaron Copland, writers Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Dorothy Parker, playwright Arthur Miller, and actor and filmmaker Orson Welles. The policy wasn’t always strictly enforced, and even during the period of its strictest enforcement, from the late 1940s through to the late 1950s. The blacklist was almost never made explicit. It was rather the result of numerous individual decisions by the studios and was not the result of official legal action. Nevertheless, the blacklist quickly and directly damaged or even ended the careers and income of scores of individuals working in the film industry.

Those blacklisted included composer Aaron Copland, writers Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Dorothy Parker, playwright Arthur Miller, and actor and filmmaker Orson Welles. The policy wasn’t always strictly enforced, and even during the period of its strictest enforcement, from the late 1940s through to the late 1950s. The blacklist was almost never made explicit. It was rather the result of numerous individual decisions by the studios and was not the result of official legal action. Nevertheless, the blacklist quickly and directly damaged or even ended the careers and income of scores of individuals working in the film industry.