Washington

I first heard about Oak Harbor, Washington when my sister, Caryl Reed and her then husband lived there while he was stationed at the nearby naval station at Whidbey Island. Now that my daughter, Amy Royce, her husband Travis and their kids Shai and Caalab live in the Bellingham area of upstate Washington, Oak Harbor has once again come into range of my radar. Oak Harbor was founded in the 1850s when three settlers staked claims where the city now stands. Martin Taftezon, a shoemaker from Norway; C.W. Sumner from New England; and Ulrich Freund, a Swiss Army officer. Freund retained part of his claim, which today is home to his descendants. The city was incorporated on May 14, 1915, and celebrated it’s 100th anniversary in 2015.

I first heard about Oak Harbor, Washington when my sister, Caryl Reed and her then husband lived there while he was stationed at the nearby naval station at Whidbey Island. Now that my daughter, Amy Royce, her husband Travis and their kids Shai and Caalab live in the Bellingham area of upstate Washington, Oak Harbor has once again come into range of my radar. Oak Harbor was founded in the 1850s when three settlers staked claims where the city now stands. Martin Taftezon, a shoemaker from Norway; C.W. Sumner from New England; and Ulrich Freund, a Swiss Army officer. Freund retained part of his claim, which today is home to his descendants. The city was incorporated on May 14, 1915, and celebrated it’s 100th anniversary in 2015.

When we visited Caryl, she took us to see one of the prettiest places in the area, known as Deception Pass. You might wonder why it is called Deception Pass. The Pass is actually a strait between the Whidbey and the Fidalgo Islands and is called “Deception” because George Vancouver was mislead by it into thinking that Whidbey Island was a peninsula. However it came to be, Deception Pass, the area is beautiful. There is also a series of 25 trails in the Deception State Park that I am interested in. I am hoping to be able to hike the area on our next visit to see our daughter and her family.

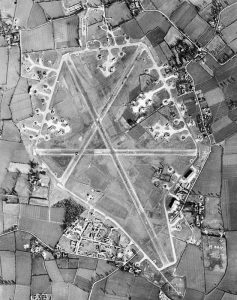

The town of Oak Harbor is Whidbey Island’s largest incorporated city. It is located in Island County. Oak Harbor was named for the Garry Oak trees which grace its skyline. The growth of Oak Harbor was really brought on by

two events…the building of Deception Pass Bridge on July 31, 1935, and the completion of Naval Air Station Whidbey Island on September 21, 1942. After that, Oak Harbor grew from a population of 362 in 1935, to 22,954 in 2018. I enjoyed our visit when my sister lived there, and even though our daughter lives further north, Oak Harbor is not too far away for a visit and maybe a hike.

two events…the building of Deception Pass Bridge on July 31, 1935, and the completion of Naval Air Station Whidbey Island on September 21, 1942. After that, Oak Harbor grew from a population of 362 in 1935, to 22,954 in 2018. I enjoyed our visit when my sister lived there, and even though our daughter lives further north, Oak Harbor is not too far away for a visit and maybe a hike.

I never thought that I would have much interest in how a guitar was made, but my grandson, Caalab Royce is interested in building guitars, so of course, I became interested too. You do that with your children and grandchildren. Caalab showed me pictures of the guitars he wanted to make, and told me that he could buy a kit to build one, that would include all the parts. I truly believe there will come a day that he will build a guitar, and it will be beautiful, and sound beautiful. I might be

I never thought that I would have much interest in how a guitar was made, but my grandson, Caalab Royce is interested in building guitars, so of course, I became interested too. You do that with your children and grandchildren. Caalab showed me pictures of the guitars he wanted to make, and told me that he could buy a kit to build one, that would include all the parts. I truly believe there will come a day that he will build a guitar, and it will be beautiful, and sound beautiful. I might be  biased, but if my grandson makes it, I know it will be perfect.

biased, but if my grandson makes it, I know it will be perfect.

Recently, I stumbled across an article about a musical wood. That caught my attention. I wondered how wood could be musical. Of course, it couldn’t, as I already knew and went on to find out, but the Sitka Spruce tree is, nevertheless, the wood used for the vast majority of acoustic guitar, piano, violin, and other musical-instrument soundboards. That told me that the wood must have some kind of musical importance. I found out that the wood has excellent acoustic properties. The wood is light, soft, and yet, relatively strong and flexible. The Sitka Spruce is also used for general construction, ship building, and plywood.

Found mostly in Southeast Alaskan forests, the Sitka Spruce is being harvested at such a rate that the end of the instrument-quality supply is in sight. That doesn’t mean that the Sitka Spruce was becoming extinct, but it takes time to grow to some size, so the instrument-quality is becoming less available. The population of the Sitka Spruce is stable at this point, and it grows in Alaska, as well as Washington, Oregon, and California,

meaning that there is plenty of places to re-seed this important tree. It really is just a matter of waiting for the growth, and when you are talking about a tree, it’s very different than a puppy. You are talking years for a tree. A Sitka Spruce grows to around 88 feet in height after 50 years, to 157 feet after 100 years. That means that by the time the trees grow to usable size, the guitar builders of today will be long gone, so a new generation will be the ones to use the new growth. I hope that Caalab will have a chance to build a guitar out of Sitka Spruce before the wood is no longer available.

meaning that there is plenty of places to re-seed this important tree. It really is just a matter of waiting for the growth, and when you are talking about a tree, it’s very different than a puppy. You are talking years for a tree. A Sitka Spruce grows to around 88 feet in height after 50 years, to 157 feet after 100 years. That means that by the time the trees grow to usable size, the guitar builders of today will be long gone, so a new generation will be the ones to use the new growth. I hope that Caalab will have a chance to build a guitar out of Sitka Spruce before the wood is no longer available.

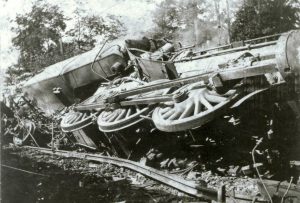

When a train derails, you know that there is going to be a big mess, and loss of life, or at the very least, injuries. And you would probably be right, but it would be a whole different situation, if multiple trains collided with each other. That is the exact scenario on January 17, 1929, in Aberdeen, Maryland, when two Pennsylvania Railroad passenger trains and a freight train all collided. While the collision was horrific, the loss of life was amazingly less that expected.

When a train derails, you know that there is going to be a big mess, and loss of life, or at the very least, injuries. And you would probably be right, but it would be a whole different situation, if multiple trains collided with each other. That is the exact scenario on January 17, 1929, in Aberdeen, Maryland, when two Pennsylvania Railroad passenger trains and a freight train all collided. While the collision was horrific, the loss of life was amazingly less that expected.

On that day, passenger train Number 412, bound from Washington to Philadelphia, struck the freight train, who was also northbound, just after it pulled from a siding, by Short Lane station, near Aberdeen. The freight cars toppled onto the southbound track, directly in front of express train Number 121, from New York to Washington. There was simply not time to avoid the disaster. The wreck killed four trainmen and seriously injured another. Conductors of the two passenger trains declared none of their passengers were seriously hurt. Brakeman, K. A. Klein, on the freight train, and flagman, V. W. Stewart, were both killed in the first crash; and engineer of the southbound express train, A. C. Terhune, and M. Goldstein, his fireman, were killed when their train ploughed into the wreckage.

Bodies of the two from the freight crew and of the passenger firemen were removed and taken to a morgue in Aberdeen, but the body of the express engineer was still under the engine five hours after the wreck. The workmen were prevented from recovering it by outpouring steam. Leon Sweeting, engineer of the northbound passenger train, was badly scalded and was taken to the Havre de Grace Hospital, where his condition was reported to be serious. John H. Lee, fireman on the same train, was in the hospital, suffering from shock.

It is thought that heavy fog in the area, prevented the engineer of northbound number 412 from seeing the tail-light of the freight train right in front of him. Some passengers on the northbound and southbound trains were said to have been slightly injured, but none was reported in serious condition. The triple crash tore up about 150 yards of track and uprooted signal and telegraph poles. Trains had to be re-routed over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad tracks, while relief trains were sent from Baltimore to Aberdeen. While this was not the worst wreck, in fatalities and injuries, I don’t recall too many, if any others involving three trains, and the experience must have been terrifying.

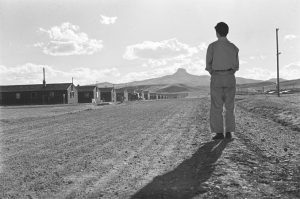

In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

In the middle of a war, the people of a nation become concerned about anyone who might potentially be the enemy, especially if they are living inside the country’s borders. It is really a natural reaction to enemy personnel. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United states became quite concerned about the Japanese immigrants in our country, whether they were here legally or not. Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884, when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which drastically restricted Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving and began to prosper and started small businesses or became farmers. Most of them settled along the West Coast, meaning roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor, heightened the level of concern about those people.

It was decided that, because their loyalties could not positively be confirmed, the Japanese immigrants needed to be rounded up and put in concentration camps. I suppose this might have seemed similar to what the Germans did to the Jewish people, but the Japanese people were not murdered in the camps, like the Jews were. And so it came to be that the people of Japanese descent from Oregon, Washington and California were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Park County, Wyoming, by the executive order of President Franklin Roosevelt. The prisoners were held at the camp from August 12, 1942 to November 10, 1945, which was actually two months after the end of the war with Japan. The camp was populated with 10,000 people at its largest, making it the third largest town in the state at the time.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like for those Japanese immigrants to be held in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center for as much as 2 years and 3 months. Of course, the illegal immigrants of our time immediately came to my mind, but there is a difference between these people and the illegal immigrants of today. These people were here legally, and most of them had already become citizens. Unfortunately, that did not calm the worried minds of the rest of the people of the United States. Our nation had been attacked, and the attackers looked just like the Japanese immigrants. Precautions had to be taken. I’d like to think that if it were me, in that position, that I would understand why this was happening, but I’m not so sure I would. After all, these people were not criminals. They were hard working Americans, and yet they were for a time…the enemy, or possibly the enemy.

Unfortunately, like many prior immigrant groups, the Japanese faced discrimination. Things aren’t always fair, and people aren’t always treated properly. Starting in the early 20th century, Japanese immigrants, as well as Chinese immigrants, were targeted by Alien Land Laws in western states including Wyoming. These laws prevented the Asian immigrants from buying land. In 1924, the United States Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act, which all but cut off new immigration from Asia. In response, Japanese Americans formed organizations such as the Japanese American Citizens’ League to help address their shared challenges. Despite  the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

the attempts of Japanese Americans to fit in, some people expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

The Heart Mountain facility consisted of 450 barracks, each containing six apartments, when the first internees arrived on August 12, 1942. The largest apartments were simply single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet. The barracks were covered with tar paper. While each unit was eventually outfitted with a potbellied stove, none had bathrooms. The people all used shared latrines. None of the apartments had kitchens. The residents ate their meals in mess halls. When the people first arrived, a barbed-wire fence to surround the camp was not yet complete. The internees protested the construction of this barrier and caused further work to be delayed. In November 1942, they submitted a petition containing 3,000 signatures to the War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Meyer. The fence was completed by December, however, and further emphasized the sense of confinement among the internees. Shortly after the construction of the fence, 32 boys were arrested for sledding in the hills beyond the boundary. In response to the perceived overreaction on the part of the camp administration, Rikio Tomo, a Heart Mountain internee, placed an editorial in the Heart Mountain Sentinel asking for clarification about the internees’ citizenship status and constitutional freedoms. Schools were built at Heart Mountain, including a high school, to accommodate the children. These schools served students from elementary school through high school. Roughly 1500 students attended Heart Mountain High School, which included grades 8-12.

The internees provided most of the labor required to run the Heart Mountain camp, while WRA administrators oversaw its general operations. Wages ranged from $12 per month for unskilled labor to $19 per month for skilled labor, including teachers for the schools and doctors in the camp hospitals. In addition, Heart Mountain internees also worked as manual laborers on farms and ranches in Wyoming and nearby states from Nebraska to Oregon. The WRA administrators encouraged activities emphasizing American civics, such as scouting and adult English classes, as part of what they saw as an Americanization process. Committees composed initially of American-born internees provided much of the day-to-day governance of the camps. While these groups provided some measure of self-determination, they disrupted the generational hierarchy. American-born adults in their 20s and 30s were given a higher political status within the camps than their Japanese-born parents.

In 1943, General George Marshall approved the creation of the Japanese-American combat unit. As a result of the low turnout, the War Department extended the draft to the camps. It was decided that while they were not free to go where they chose, these people were needed to serve their country, so a draft was instituted. After they were drafted into the U.S. Army, soldiers from Heart Mountain occasionally returned to visit their families who were still held there. Somehow that doesn’t seem quite fair to me, and many of the prisoners agreed. They thought they should have been given their constitutional rights back before they were drafted. The organization of draft resistance distinguished Heart Mountain from the other relocation centers. The plan, which was given the endorsement of President Roosevelt, was to create an all-Japanese regiment, consisting of soldiers from a previously existing Hawaiian unit and volunteers from the camps. The response from within the camps fell far short of expectations, partly because of a loyalty questionnaire distributed by the WRA. The WRA form was used to determine eligibility for military service and permanent leave. Many of the questions were considered intrusive by prisoners. Others were not as straightforward as the WRA probably intended. Instead of serving as a neutral tool to determine someone’s suitability for service, the questionnaire further alienated many the men. To me it seems that the WRA was somehow not aware of how racist the entire situation really was. For example, question 27 asked about a person’s willingness to serve in the military. For

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

prisoners who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient. In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some prisoners felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service. I doubt if the situation would have ever really been resolved, except that the war ended.

With the eruption and possible explosion of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii, my thoughts are drawn back 38 years to another mountain…Mount Saint Helens. The scientists said that an explosive eruption was imminent. The mountain had been swelling up with internal pressure from the gasses deep in the earth. Still, some people didn’t believe the mountain would ever hurt them, and many just couldn’t wrap their head around the possibility that it might explode. So, some people stayed in their homes in the area. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

With the eruption and possible explosion of the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii, my thoughts are drawn back 38 years to another mountain…Mount Saint Helens. The scientists said that an explosive eruption was imminent. The mountain had been swelling up with internal pressure from the gasses deep in the earth. Still, some people didn’t believe the mountain would ever hurt them, and many just couldn’t wrap their head around the possibility that it might explode. So, some people stayed in their homes in the area. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

It’s strange that we are able to associate things in life with major events in recent history. Many of us can say where we were when we learned of President Kennedy’s assassination, or when 9-11 took place. It is a moment that is embedded in our memories for all time. That morning as the ash rolled into our area, I was getting into my car to go to town. It looked like dust on my car, a very thick layer of dust. Of course, it wasn’t dust, it was volcanic  ash. It had never occurred to me that volcanic ash might affect me, but here I was, needing to wash the ash off of my car, so it was not damaged.

ash. It had never occurred to me that volcanic ash might affect me, but here I was, needing to wash the ash off of my car, so it was not damaged.

My cousin, Shirley, who lives in Washington, said she and her family were in Spokane. She saw a black cloud coming their way, and so she turned on the radio, to see what was going on. She immediately started yelling to the teachers and students from Saint Matthews school, who were at an end of the year baseball game. Every one scrambled to get their belongings, and headed back to the Church, before heading for home. Navigation became difficult. They had to watch the curb on the side of the streets to know where they were. It was a long drive home. They held their breath from the truck to the house, to protect their lungs, and watched the street lights come on. Shirley went out on the front porch and took pictures,  before retreating back to the safety of her house. They were forced to stay in the house for about a week, before it was safe to out again. Many safety precautions were in place, and people were told not to breathe the ash because of the glass in it.

before retreating back to the safety of her house. They were forced to stay in the house for about a week, before it was safe to out again. Many safety precautions were in place, and people were told not to breathe the ash because of the glass in it.

Mount Saint Helens is located in the Cascade Range. On May 18, 1980, at 8:32am Pacific Standard Time, it erupted and blasted 1,300 feet off of its top, sending hot mud, gas, and ash running down its slopes. Approximately 57 people were killed directly from the blast, while 200 houses, 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways, and 185 miles of highway were destroyed. Two people were killed indirectly in accidents that resulted from poor visibility, and two more suffered fatal heart attacks from shoveling ash. The explosion sent plumes of dark gray ash some 60,000 feet in the air which blocked out the rays from the sun making it seem like night over eastern Washington. So…where were you when Mount Saint Helens blew?

Most of the time, when we think of time and distance here on planet earth, we tend to feel like we are just a speck compared to the size of this planet, and I suppose that is true, but sometimes, our connection to one another is, in reality, much closer than we know. My dad, Allen L “Al” Spencer was a top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber in World War II. He was stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. I have always been very proud of my dad’s service, and because of his service, I have also always had an interest in other World War II bases in England.

Most of the time, when we think of time and distance here on planet earth, we tend to feel like we are just a speck compared to the size of this planet, and I suppose that is true, but sometimes, our connection to one another is, in reality, much closer than we know. My dad, Allen L “Al” Spencer was a top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber in World War II. He was stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. I have always been very proud of my dad’s service, and because of his service, I have also always had an interest in other World War II bases in England.

Yesterday, while researching my husband Bob’s great uncle, Richard F “Frank” Knox for his birthday today, I found myself reading his obituary again, looking for more information on a man I admired. I have always liked Frank very much, but because of the fact that we lived in Wyoming and they lived in Washington, I can’t say that I knew about his everyday life, and I certainly didn’t know about his military career. That said, while I had read the obituary right after his passing July 13, 2017, somehow it didn’t  hit me that he was stationed as a communications officer at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. Of course, my curious mind had to go to Google Earth. I wanted to know if the Air Base was still visible, because most of them have been in one way or another returned to farm land. I did find the base, and while it’s outline isn’t as clearly marked as Great Ashfield is, I could pick out RAF Horham too. After finding the base, I was able to imagine a young Uncle Frank living and working there during the war. To me, that thought was very interesting, but another thing I noticed was the fact that Horham was not that far from Great Ashfield. In fact, my dad and Bob’s Uncle Frank were stationed a mere 22 miles away from each other. It is doubtful that they ever met, and if they did, they probably wouldn’t remember it, because it would be just in passing, but it occurs to me now, that the two men have probably met in Heaven, and they probably had some interesting stories to tell about their time in England.

hit me that he was stationed as a communications officer at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. Of course, my curious mind had to go to Google Earth. I wanted to know if the Air Base was still visible, because most of them have been in one way or another returned to farm land. I did find the base, and while it’s outline isn’t as clearly marked as Great Ashfield is, I could pick out RAF Horham too. After finding the base, I was able to imagine a young Uncle Frank living and working there during the war. To me, that thought was very interesting, but another thing I noticed was the fact that Horham was not that far from Great Ashfield. In fact, my dad and Bob’s Uncle Frank were stationed a mere 22 miles away from each other. It is doubtful that they ever met, and if they did, they probably wouldn’t remember it, because it would be just in passing, but it occurs to me now, that the two men have probably met in Heaven, and they probably had some interesting stories to tell about their time in England.

As big as this old world is, and as unlikely as it seems that two families could have some close connections like this, I find that at least in my life, and my husband’s life, there are some connections, some very near misses, and some interesting encounters. Like my dad, Uncle Frank served out his time in the Army Air Forces right there

at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. I imagine that like my dad, Frank took at least one leave to go and see London, because how could you go to England and not see London. Frank had a successful career in communications and then after his discharge from the service, four years, four months and four days of active duty, separating at war’s end with the rank of major. Frank served with distinction, earning a Bronze Star and the Air Medal, then he continued his military career in the Air Force Reserve. He retired in 1968 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Today would have been Uncle Frank’s 98th birthday, and it is his first in Heaven. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Frank. We love and miss you very much.

at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. I imagine that like my dad, Frank took at least one leave to go and see London, because how could you go to England and not see London. Frank had a successful career in communications and then after his discharge from the service, four years, four months and four days of active duty, separating at war’s end with the rank of major. Frank served with distinction, earning a Bronze Star and the Air Medal, then he continued his military career in the Air Force Reserve. He retired in 1968 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Today would have been Uncle Frank’s 98th birthday, and it is his first in Heaven. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Frank. We love and miss you very much.

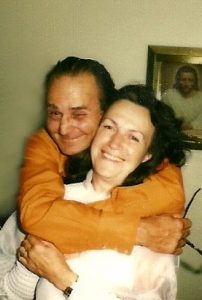

My Aunt Ruth Wolfe was raised on a farm, around horses, and she loved them, as well as most other animals. She really thrived on the country life. She worked hard, alongside her mom and siblings, especially during World War II, when her brother, my dad, Allen Spencer was serving in the Army Air Forces. She helped at the farm and also as a welder at the shipyards…one of the women known as riveters. Later in her life, when she was married, she and my Uncle Jim Wolfe lived in the country outside Casper, Wyoming. They gardened, canned, and raised farm animals. Aunt Ruth was one tough lady. She could do just about anything she set her mind to. From that hard work of farming, to canning, to haying, to playing any instrument, to painting, my Aunt Ruth was simply a multi-talented woman.

My Aunt Ruth Wolfe was raised on a farm, around horses, and she loved them, as well as most other animals. She really thrived on the country life. She worked hard, alongside her mom and siblings, especially during World War II, when her brother, my dad, Allen Spencer was serving in the Army Air Forces. She helped at the farm and also as a welder at the shipyards…one of the women known as riveters. Later in her life, when she was married, she and my Uncle Jim Wolfe lived in the country outside Casper, Wyoming. They gardened, canned, and raised farm animals. Aunt Ruth was one tough lady. She could do just about anything she set her mind to. From that hard work of farming, to canning, to haying, to playing any instrument, to painting, my Aunt Ruth was simply a multi-talented woman.

I think one of the strangest moves Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim made was the one to Vallejo, California. I couldn’t quite figure out why a person who loved the country so much, would move to a city. Vallejo is a suburb of San Francisco, California, and very different from Casper, Wyoming or Holyoke, Minnesota. I suppose they decided that they wanted a change of pace, and I can understand that, because my family and I lived in the country for a number of years before we moved into town in Casper. For us, the city life was more…us, at least the small city life. I don’t think I would want to live in a big city like New York or San Francisco. Still, I can understand why my aunt and uncle might be drawn to the big city life, and the warmer California weather.

After a time in California, the quiet country life again drew them from the big city to the mountains of Washington state. I can’t say that the move to the mountains surprised me much, because it seems like country life was like the blood that ran through my aunt and uncle’s veins. It was a part of who they were, as

much as their DNA was who they were. Once they settled in eastern Washington, they never moved again. They bought the top of a mountain, and built three cabins there…one for them, one for their daughter, Shirley and her husband, Shorty Cameron; and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this would be their forever home. Having been on their mountain top, I can say that I understand why they thought it was so beautiful, but in the years since I moved back to town, I know that I would not want to live permanently in the country, or on a mountain top again. Nevertheless, that was their favorite place to be. Today would have been my Aunt Ruth’s 92nd birthday. It’s hard to believe she has been gone 26 years now. Happy birthday in Heaven Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you so very much, and can’t wait to see you again.

much as their DNA was who they were. Once they settled in eastern Washington, they never moved again. They bought the top of a mountain, and built three cabins there…one for them, one for their daughter, Shirley and her husband, Shorty Cameron; and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this would be their forever home. Having been on their mountain top, I can say that I understand why they thought it was so beautiful, but in the years since I moved back to town, I know that I would not want to live permanently in the country, or on a mountain top again. Nevertheless, that was their favorite place to be. Today would have been my Aunt Ruth’s 92nd birthday. It’s hard to believe she has been gone 26 years now. Happy birthday in Heaven Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you so very much, and can’t wait to see you again.

The old West was a rugged, unforgiving place, and for a long time it was thought to be a man’s place, and completely unsafe for women. Men went west, mined for gold, and came home to their families. A man would have to be insane to bring his wife and children to the West. Nevertheless, it was really only a matter of time before someone decided that the west was going to be settled, and it was going to take both men and women to settle the West…otherwise it was always going to be a job site and not a home. Someone had to make the first move, and I can imagine how the parents of those first women must have felt when their daughters told them they were moving out west. It must have been like thinking, “who was this idiot their daughter has married!” Of course, women had come as far as the Rocky Mountains, so going further wasn’t that strange, but it was still the unknown.

The old West was a rugged, unforgiving place, and for a long time it was thought to be a man’s place, and completely unsafe for women. Men went west, mined for gold, and came home to their families. A man would have to be insane to bring his wife and children to the West. Nevertheless, it was really only a matter of time before someone decided that the west was going to be settled, and it was going to take both men and women to settle the West…otherwise it was always going to be a job site and not a home. Someone had to make the first move, and I can imagine how the parents of those first women must have felt when their daughters told them they were moving out west. It must have been like thinking, “who was this idiot their daughter has married!” Of course, women had come as far as the Rocky Mountains, so going further wasn’t that strange, but it was still the unknown.

On this day in 1836, Narcissa Whitman arrived in Walla Walla, Washington, becoming one of the first Anglo women to settle west of the Rocky Mountains. Narcissa and Marcus Whitman, along with their close friends Eliza and Henry Spalding, had departed from New York earlier that year on the long overland journey to the far western edge of the continent. These days, that trip can be  made in a matter of hours, but in those days, it took lots of planning and months to accomplish such a trip. The two couples were missionaries, and Narcissa wrote that they were determined to convert the “benighted ones” living in “the thick darkness of heathenism” to Christianity. I guess there was no specific word for Indians, or Native Americans back then, or she just liked her version better. Mission work was one of the big reasons for heading west…besides land, and gold, of course.

made in a matter of hours, but in those days, it took lots of planning and months to accomplish such a trip. The two couples were missionaries, and Narcissa wrote that they were determined to convert the “benighted ones” living in “the thick darkness of heathenism” to Christianity. I guess there was no specific word for Indians, or Native Americans back then, or she just liked her version better. Mission work was one of the big reasons for heading west…besides land, and gold, of course.

That summer when they crossed the continental divide at South Pass, Narcissa and Eliza became the first Anglo-American women in history to travel west of the Rocky Mountains. I suppose it was like going to another planet to the women, who went with no real idea of what they would be facing in the new frontier. Toward the end of their difficult 1,800 mile journey, the two couples split up, with the Spaldings heading for Idaho while  Narcissa and her husband traveled to a settlement near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, where they established a mission for the Cayuse Indians. I can only imagine how the two women must have felt, knowing that it would be a very long time before they had the company of another Anglo woman. For 11 years the couples’ missionary work went well, and they succeeded in converting many of the Cayuse to Christianity. Then in 1847, a devastating measles epidemic swept through the area, killing many of the Cayuse, who had no immunity to the disease, while leaving most of the white people at the mission suspiciously unharmed. Convinced that the missionaries or their god had cursed them with an evil plague, a band of the Cayuse Indians attacked the mission and killed 14 people, including Narcissa and her husband on November 29, 1847. Narcissa Whitman thus became not only one of the first white women to live in the Far West, but also one of the first white women to die there too. She was just 39 years old at the time she was murdered.

Narcissa and her husband traveled to a settlement near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, where they established a mission for the Cayuse Indians. I can only imagine how the two women must have felt, knowing that it would be a very long time before they had the company of another Anglo woman. For 11 years the couples’ missionary work went well, and they succeeded in converting many of the Cayuse to Christianity. Then in 1847, a devastating measles epidemic swept through the area, killing many of the Cayuse, who had no immunity to the disease, while leaving most of the white people at the mission suspiciously unharmed. Convinced that the missionaries or their god had cursed them with an evil plague, a band of the Cayuse Indians attacked the mission and killed 14 people, including Narcissa and her husband on November 29, 1847. Narcissa Whitman thus became not only one of the first white women to live in the Far West, but also one of the first white women to die there too. She was just 39 years old at the time she was murdered.

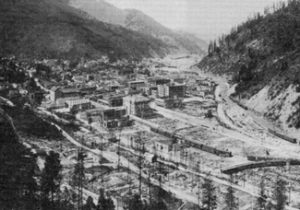

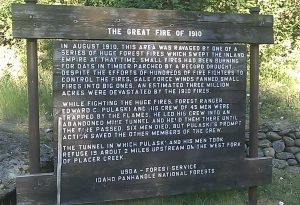

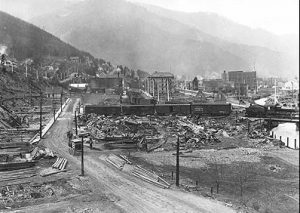

With summer, and especially late summer, when things are beginning to dry up, comes an increased danger of wildfires. Add to that, an extremely dry spring and early summer, and you have a recipe for disaster. Such was the case in northwest Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana in 1910. There were a great number of problems that contributed to an over active fire season, and ultimately, the destruction that began on August 20, 1910, quickly became a firestorm that burned about three million acres…a full 4,700 square miles before it was over. The areas burned included parts of the Bitterroot, Cabinet, Clearwater, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Saint Joe National Forests. The extensive burned area was approximately the size of the state of Connecticut. The extreme scorching heat of the sudden blowup can be attributed to the great Western White Pine forests that blanketed Idaho. The hydrocarbons in the resinous sap boiled out and created a cloud of highly flammable gas that blanketed hundreds of square miles, which then spontaneously detonated dozens of times, each time sending tongues of flame thousands of feet into the sky, and creating a rolling wave of fire that destroyed anything and everything in its path.

With summer, and especially late summer, when things are beginning to dry up, comes an increased danger of wildfires. Add to that, an extremely dry spring and early summer, and you have a recipe for disaster. Such was the case in northwest Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana in 1910. There were a great number of problems that contributed to an over active fire season, and ultimately, the destruction that began on August 20, 1910, quickly became a firestorm that burned about three million acres…a full 4,700 square miles before it was over. The areas burned included parts of the Bitterroot, Cabinet, Clearwater, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Saint Joe National Forests. The extensive burned area was approximately the size of the state of Connecticut. The extreme scorching heat of the sudden blowup can be attributed to the great Western White Pine forests that blanketed Idaho. The hydrocarbons in the resinous sap boiled out and created a cloud of highly flammable gas that blanketed hundreds of square miles, which then spontaneously detonated dozens of times, each time sending tongues of flame thousands of feet into the sky, and creating a rolling wave of fire that destroyed anything and everything in its path.

That summer had been described as “like no others.” The drought resulted in forests that were filled with dry fuel, which had previously grown up on abundant autumn and winter moisture. Fires were set by hot cinders flung from locomotives, sparks, lightning, and backfiring crews, and by mid-August, there were 1,000 to 3,000 fires burning in Idaho, Montana, Washington, and British Columbia. Then on August 20th, everything blew up into a firestorm. The firestorm burned over two days, August 20 and 21. It killed 87 people, most of them firefighters. The entire 28 man “Lost Crew” was overcome by flames and perished on Setzer Creek in Idaho outside of Avery. The Great Fire of 1910 is believed to be the largest, although not the deadliest, forest fire in United States history. It was commonly referred to as the Big Blowup, the Big Burn, or the Devil’s Broom fire. Smoke from the fire could be seen as far east as Watertown, New York, and as far south as Denver, Colorado. It was reported that at night, five hundred miles out into the Pacific Ocean, ships could not navigate by the stars because the sky was cloudy with smoke.

The fire actually started as many small fires. Then, on August 20, a cold front blew in and brought hurricane-force winds. The wind whipped the hundreds of small fires into one or two blazing infernos. The larger fires were impossible to fight. They simply didn’t have the manpower, or the supplies. The United States Forest Service…then called the National Forest Service…was only five years old at the time and unprepared for the possibilities of this dry summer. Later, at the urging of President William Howard Taft, the United States Army, 25th Infantry Regiment…known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was brought in to help fight the blaze. The most famous story of survival was that of Ed Pulaski, a United States Forest Service ranger who led a large group of his men to safety in an abandoned prospect mine outside of Wallace, Idaho, just as they were about to be overtaken by the fire. Pulaski fought off the flames at the mouth of the shaft until he passed out like the other men. Around midnight, one man said that he was getting out of there. Knowing that they would have no

chance of survival if they ran, Pulaski drew his pistol. He threatened to shoot the first person who tried to leave. In the end, all but five of the forty or so men survived. Several towns were completely destroyed by the fire. The fire was finally extinguished when another cold front swept in, bringing with it, steady rain. Unfortunately, it was too late for the 87 people who lost their lives in the blaze. Memorials were placed in several of the fire areas.

chance of survival if they ran, Pulaski drew his pistol. He threatened to shoot the first person who tried to leave. In the end, all but five of the forty or so men survived. Several towns were completely destroyed by the fire. The fire was finally extinguished when another cold front swept in, bringing with it, steady rain. Unfortunately, it was too late for the 87 people who lost their lives in the blaze. Memorials were placed in several of the fire areas.

After the Revolutionary War, and the United States independence that followed, the relationship between the two nations was quite strained. The United States did not like having British military posts on our northern and western borders, and Britain’s violation of American neutrality in 1794 when the Royal Navy seized American ships in the West Indies during England’s war with France. Finally, in an attempt to smooth things over, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, who was appointed by President Washington, came up with a treaty. The treaty officially known as the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America” was signed by Britain’s King George III on November 19, 1794 in London. However, after Jay returned home with news of the treaty’s signing, President Washington, who was now in his second term, had encountered fierce Congressional opposition to the treaty. By 1795, its ratification was still uncertain, and there was work to be done to change things.

After the Revolutionary War, and the United States independence that followed, the relationship between the two nations was quite strained. The United States did not like having British military posts on our northern and western borders, and Britain’s violation of American neutrality in 1794 when the Royal Navy seized American ships in the West Indies during England’s war with France. Finally, in an attempt to smooth things over, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, who was appointed by President Washington, came up with a treaty. The treaty officially known as the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America” was signed by Britain’s King George III on November 19, 1794 in London. However, after Jay returned home with news of the treaty’s signing, President Washington, who was now in his second term, had encountered fierce Congressional opposition to the treaty. By 1795, its ratification was still uncertain, and there was work to be done to change things.

The two biggest opponents to the treaty were two future presidents…Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson was, at the time, in between political positions. He had just completed a term as Washington’s secretary of state from 1789 to 1793 and had not yet become John Adams’ vice president. Fellow Virginian, James Madison was a member of the House of Representatives. Jefferson, Madison and other opponents feared the treaty gave too many concessions to the British. They argued that Jay’s negotiations actually weakened American trade rights and complained that it committed the United States to paying pre-revolutionary debts to English merchants. Washington himself was not completely satisfied with the treaty, but considered preventing another war with America’s former colonial master a priority.

The treaty was finally approved by Congress on August 14, 1795, with exactly the two-thirds majority it needed

to pass. President Washington signed the treaty just four days later, on August 18, 1795. Washington and Jay may have won the legislative battle and averted war temporarily, but it created a conflict at home that highlighted a deepening division between those of different political ideologies in Washington DC, much like what we see these days. Jefferson and Madison mistrusted Washington’s attachment to maintaining friendly relations with England over revolutionary France, who would have welcomed the United States as a partner in an expanded war against England.

to pass. President Washington signed the treaty just four days later, on August 18, 1795. Washington and Jay may have won the legislative battle and averted war temporarily, but it created a conflict at home that highlighted a deepening division between those of different political ideologies in Washington DC, much like what we see these days. Jefferson and Madison mistrusted Washington’s attachment to maintaining friendly relations with England over revolutionary France, who would have welcomed the United States as a partner in an expanded war against England.