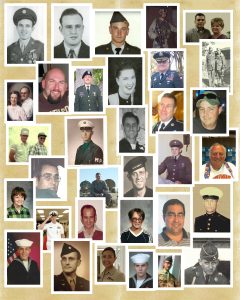

soldiers

In a time when our nation is in such turmoil, I find myself appreciating our veterans even more than I did before. As a proud daughter of a World War II veteran, I always had a feeling of awe when it came to the members of our military. I never thought of a soldier without associating it with a hero, because that is what they are…each and every one of them. It takes the heart of a hero to set aside their own life, time with family, and their safety to protect the rights and lives of others…people they don’t know…who aren’t in their own country.

In a time when our nation is in such turmoil, I find myself appreciating our veterans even more than I did before. As a proud daughter of a World War II veteran, I always had a feeling of awe when it came to the members of our military. I never thought of a soldier without associating it with a hero, because that is what they are…each and every one of them. It takes the heart of a hero to set aside their own life, time with family, and their safety to protect the rights and lives of others…people they don’t know…who aren’t in their own country.

Soldiers are a special kind of hero. Like our first responders, they run into danger while others are running away, but a soldier does that in countries that aren’t their own. They have no stake in that country, but they know that without their help, the people of that nation are going to continue to live oppressed. The soldier fights for those who cannot fight for themselves. Evil dictators cringe when the soldiers are sent in, because there is a good possibility that the dictator’s days are numbered. War is never an easy journey for the soldier, but he or she knows that they are needed. They know that for every enemy death…a life is saved, and while that may be putting things a little bit simplistically, in a very real sense, it is true. In a war, the enemy must be beaten, in order to win the war, and thereby save the innocent.

Going off to war changes a person, and so does training to go to war. The minute a soldier joins up, there is a possibility of going to war, and the soldier has to face that fact. That’s where the heart of the hero kicks in. Deep down inside, the soldier has knows that what they are doing is important…it matters. Theirs is often a thankless job, and is sometimes treated with great disrespect, but when they are needed, they answer the call, nevertheless. It is our soldiers and their strength, that usually keeps our homeland free from attack. It’s not that we have never had attacks on our soil, but a strong, at the ready military force, makes our enemies think twice about trying to attack us here…and for that, I thank our military men and women. Our nation is very blessed to have our soldiers. To our active duty soldiers and our veterans of all wars, Happy Veterans Day!!

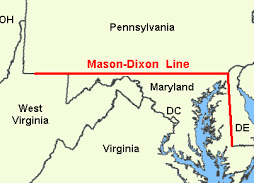

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

When Mason and Dixon began their endeavor in 1763, colonists were protesting the Proclamation of 1763, which was intended to prevent colonists from settling beyond the Appalachians and angering Native Americans. In reality, expansion was inevitable, but many in government couldn’t seem to see that. As the Mason and Dixon concluded their survey in 1767, the colonies were engaged in a dispute with the Parliament over the Townshend Acts, which were designed to raise revenue for the British empire by taxing common imports including tea. A protest that resulted in the Boston Tea Party, but that is another story. Twenty years later, in late 1700s, the states south of the Mason-Dixon line would begin arguing for the perpetuation of slavery in the new United States while those north of line hoped to phase out the ownership of human property. This period, which historians consider the era of “The New Republic,” drew to a close with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which accepted the states south of the line as slave-holding and those north of the line as free. The compromise, along with those that followed it, eventually failed, and slavery was forbidden with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862.

One hundred years after Mason and Dixon began their effort to chart the boundary, soldiers from opposite

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

The German and Finnish forces besieged Lenin’s namesake city after their spectacular initial advance during Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941. Nevertheless, it was not going to be an easy task to bring the Soviet people into submission. A German Army Group struggled against stubborn Soviet resistance to isolate and seize the city before the onset of winter. The fighting was heaviest during August. German forces reached the city’s suburbs and the shores of Lake Ladoga, severing Soviet ground communications with the city. In  November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

After November 1941, possession of Leningrad held only symbolic significance. In holding the “ice and water road” the Soviets were able to bring in enough supplies to stave of the ongoing starvation, so the siege has a  little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.

little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.

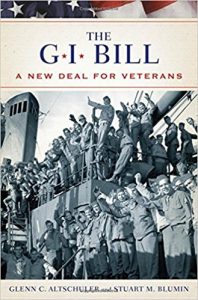

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

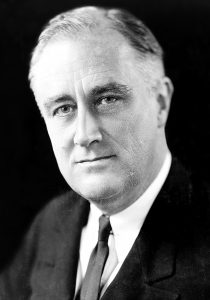

President Franklin D Roosevelt was responsible for the sweeping New Deal reforms, many of which were really not good for this nation or its people, but there was one part of that legislation that has been a good thing for returning veterans…the G.I. Bill. On this day June 22, 1944, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill. It was an unprecedented act of legislation designed to compensate returning members of the armed services, known as G.I.s, for their efforts in World War II. The G.I. Bill…officially the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944…was proposed in an effort to avoid a relapse into the Great Depression after the war ended. The American Legion, a veteran’s organization, successfully fought for many of the provisions included in the bill, which gave returning servicemen the compensations they now have. By giving veterans money for tuition, living expenses, books, supplies and  equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

As educational institutions opened their doors to this diverse new group of students, overcrowded classrooms and residences prompted widespread improvement and expansion of university facilities and teaching staffs. The bill was not only good for the veterans, but also for the economy, as more teaching jobs were created. An array of new vocational courses were developed across the country, including advanced training in education, agriculture, commerce, mining and fishing…skills that had previously been taught only informally. Some of these classes are responsible for some of the jobs that everyday Americans, even those without college educations have held. Jobs such as mining, and farming, and even fishing became commonplace.

The G.I. Bill became one of the major forces for economic expansion in America that lasted 30 years after World War II. Only 20% of the money set aside for unemployment compensation under the bill was given out. Most veterans found jobs or pursued higher education. Low interest loans enabled millions of American families to move out of cities and buy or build homes outside the city, changing the face of the suburbs. Over 50 years, the impact of the G.I. Bill was enormous, with 20 million veterans and dependents using the education benefits and 14 million home loans guaranteed, for a total federal investment of $67 billion. Among the millions of Americans who have taken advantage of the bill are former Presidents George H.W. Bush and Gerald Ford, former Vice President Al Gore and entertainers Johnny Cash, Ed McMahon, Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood, and closer to home, my brother-in-law, Ron Schulenberg, as well as my nephew, Allen Beach and soon, his wife, Gabby.

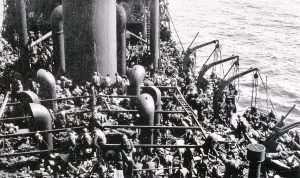

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

Operation Aerial began on June 15, 1940 and ended on June 25, 1940. Following the military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germany, it became evident that Allied soldiers and civilians were in grave danger. With two-thirds of France now occupied by German troops, those British and Allied troops that had not participated in Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of Dunkirk, were shipped home, but there remained a concern for the areas from Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, and Nantes. While these men were not under the immediate threat of assault, as at Dunkirk, they were by no means safe, so Brits, Poles, and Canadian troops were rescued from occupied territory by boats sent from Britain. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered words of encouragement in a broadcast to the nation, “Whatever has happened in France…we shall defend our island home, and with the British Empire we shall fight on unconquerable until the curse of Hitler is lifted.” This was his way of promising that Britain would never fall under Nazi rule.

Operation Aerial was split into two sectors. Admiral James, based at Portsmouth, was to control the evacuation from Cherbourg and St Malo, while Admiral Dunbar-Nasmith, the commander-in-chief of the Western Approaches, based at Plymouth, would control the evacuation from Brest, St. Nazaire and La Pallice. Eventually this western evacuation would extend to include the ports on the Gironde estuary, Bayonne and St Jean-de-Luz. Once the people were on board, I’m sure they thought they were finally safe, but that was not necessarily the case. The Germans attacked the rescue boats. Among those rescued from the shores of France, were 5,000 soldiers and French civilians on board the ocean liner Lancastria, which had picked them up at St. Nazaire. Germans bombers sunk the liner on June 17, 1940, and 3,000 passengers drowned. Churchill ordered that news of the Lancastria not be broadcast in Britain, fearing the effect it would have on public morale, since everyone was already worried about a possible German invasion now that only a channel separated them. The British public would eventually find out, but not for another six weeks, when the news broke in the United States. They would also receive the good news that Hitler had no immediate plans for an invasion of the British isle, “being well aware of the difficulties involved in such an operation,” reported the German High Command.

In the end, the evacuations dubbed Operation Dynamo and Operation Aerial, were successful, in that most of those who were evacuated made it home. I’m sure that the retreats did not feel like a success or a victory to the soldiers fighting in the Battle of France, but I am also sure that they were thankful to be among those who made it home. They would live to fight another day in the horrendous war that was World War II.

On this D-Day, a subject I have previously written about, I began to wonder about a different side of the story of this age old battle that everyone has heard of, even if some don’t know what it was all about. My thoughts turned to General Eisenhower. It was he who had the unfortunate task of deciding to attack the Germans who were occupying France, by way of the beaches of Normandy, France. It was he who had to carry the emotional burden of knowing that if the attack was made, he would be sending men to die. I would not have wanted to be in his shoes as he pondered this monumental decision. Nevertheless, someone had to make the decision. Things could not go on as they were. The future of the free world was dependent on the decisions made by this one man.

On this D-Day, a subject I have previously written about, I began to wonder about a different side of the story of this age old battle that everyone has heard of, even if some don’t know what it was all about. My thoughts turned to General Eisenhower. It was he who had the unfortunate task of deciding to attack the Germans who were occupying France, by way of the beaches of Normandy, France. It was he who had to carry the emotional burden of knowing that if the attack was made, he would be sending men to die. I would not have wanted to be in his shoes as he pondered this monumental decision. Nevertheless, someone had to make the decision. Things could not go on as they were. The future of the free world was dependent on the decisions made by this one man.

As families listened to their radio stations on the morning of June 6, 1944, one Valerie Lauder, who was 18 at the time, had graduated from Stephens Junior College that May and was not due at Northwestern University and the Medill School of Journalism until September was among the listeners. Her father was listening too, until he had to go to work. She said that President Roosevelt came on the radio and offered a prayer. Then, she heard General Eisenhower’s recorded reading of the order of the day, the troops in LSTs and transports heard it over loudspeakers. At that point, Val decided that she would really like to meet General Eisenhower, and given her chosen profession as a journalist, she was able to eventually make that happen. In fact, she was not only able to meet General Eisenhower 2½ years later, but was also able to preside at his press conference with the student press club that she had created and the Chicago Daily News sponsored.

She related the scene, “On January 18, 1947, Wearing two battle ribbons on his waist-length “Eisenhower jacket,” the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe stood to my left, facing 165 student editors and photographers from high school and college newspapers throughout the greater Chicago area gathered in the Drake Hotel. Dressed in their Sunday best, pencils poised, notebooks open, they were seated on straight-back chairs set out in rows of 10 on either side of a center aisle. Ike stood at the end of the center aisle, about three feet in front of me. I introduced him.” As Val introduced General Eisenhower, she asked him, “General Eisenhower, what was the greatest decision you had to make during the war?” Eisenhower contemplated her question for a moment, and then answered her in a somber and serious tone about the D-Day landings. “To ensure the success of the Allied landings in Normandy,” he explained, “it was imperative that we prevent the enemy from bringing up reinforcements. All roads and rail lines leading to the areas of fighting on and around the beaches had to be cut or blocked. If reinforcements were allowed to reach the areas of fighting there, in our first, precarious attempts to get a foothold on the continent, the whole operation could be jeopardized. The landings might fail. The success of the landings on the beaches,” Ike said, reaching the end of the first row, starting back, “might well turn on the success of the paratroopers behind the lines.”

Then, on May 30, just six days before the scheduled landings, which were to have been June 5, a trusted aide and personal friend came to him, deeply concerned about the airborne landing. Val later that learned it was British Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, who had been assigned to the Allied forces, with the title of Air Commander in Chief, which made him the air commander of the Allied invasion. He was apologetic about how late it was, so close to the jump-off time. But, he’d gone over it, and over it, and over it, and felt it simply would not succeed. The casualties would be too great. He pleaded with Eisenhower. “Casualties to glider troops would be 90% before they ever reached the ground,” he said. “The killed and wounded among the paratroopers would be 75%.” Eisenhower knew that would mean an unbearably high percentage of the 18,000 men who would drop into the darkness over Nazi-occupied France would become casualties. This would also mean that the survivors would be too few in number to succeed in their crucial mission of seizing, and holding the causeways. “The man was absolutely sincere, absolutely convinced it wouldn’t work,” Eisenhower said. “As a highly respected, capable officer, I trusted his judgment. I told him I’d think it over.”

After agonizing over the possible losses, he was still undecided just four days before the planned date. Eisenhower slowing, turned to face the students, he said, “I let the order stand.” With the words, his face seemed to relax. I suppose you would have to decide that you were going to be ok with the decision, or else it

would drive you crazy. The students sat in stunned silence. “The airborne boys did their job.” Eisenhower went on with relief almost bordering on elation. “And, I am happy to say, the casualties were only 8%.” Eisenhower was not just a general setting up a battle, but rather a man with a heartfelt concern for the men in the airborne divisions and the men in the landing craft headed for the beaches. As he put it in his book, Crusade in Europe, “It would be difficult to conceive of a more soul-racking problem.” I have to agree. To only lose 8% of the men in that situation, well that is…unbelievable!!

would drive you crazy. The students sat in stunned silence. “The airborne boys did their job.” Eisenhower went on with relief almost bordering on elation. “And, I am happy to say, the casualties were only 8%.” Eisenhower was not just a general setting up a battle, but rather a man with a heartfelt concern for the men in the airborne divisions and the men in the landing craft headed for the beaches. As he put it in his book, Crusade in Europe, “It would be difficult to conceive of a more soul-racking problem.” I have to agree. To only lose 8% of the men in that situation, well that is…unbelievable!!

Memorial Day…the day we set aside to remember the heroes of our wars, who paid the ultimate price for the freedoms we hold dear. The men and women who were killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor come to mind, as do those lost on the beaches of Normandy, but there are so many others. From the fliers, to the foot soldiers, to the sailors…men and women, from the Revolutionary War, to the War on Terror, have set aside their goals in life, left their families at home, pushed back their fears, and done their duty to serve their country, and for so many of them, it was a one way ticket over there. They fought and died so that someone they didn’t know could be free and have the rights that so many take for granted. They looked away when they were protested, but deep down they wondered why people didn’t understand. They tried not to watch the news of death and destruction. They just did their job, until they lost their lives in a war they wished had never started.

Memorial Day…the day we set aside to remember the heroes of our wars, who paid the ultimate price for the freedoms we hold dear. The men and women who were killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor come to mind, as do those lost on the beaches of Normandy, but there are so many others. From the fliers, to the foot soldiers, to the sailors…men and women, from the Revolutionary War, to the War on Terror, have set aside their goals in life, left their families at home, pushed back their fears, and done their duty to serve their country, and for so many of them, it was a one way ticket over there. They fought and died so that someone they didn’t know could be free and have the rights that so many take for granted. They looked away when they were protested, but deep down they wondered why people didn’t understand. They tried not to watch the news of death and destruction. They just did their job, until they lost their lives in a war they wished had never started.

Most of us knew very few soldiers who lost their lives in defense of their country, and some of us may not have known any at all, even though some of our ancestors might have been casualties of a war. I think that sometimes the families of the lost feel alone in their grief. Unless someone has been in that position, they have a difficult time really understanding the depth of the loss. People try to be understanding, imagining how they would feel if it was them, but the reality is that our imaginations are not that good. Those who have lost a loved one to war can never forget the loss or the grief they feel. Grief has no timetable, and some pain just never goes away. No pain is more horrible than losing your child, and losing them in war, seriously compounds that pain.

Most of us knew very few soldiers who lost their lives in defense of their country, and some of us may not have known any at all, even though some of our ancestors might have been casualties of a war. I think that sometimes the families of the lost feel alone in their grief. Unless someone has been in that position, they have a difficult time really understanding the depth of the loss. People try to be understanding, imagining how they would feel if it was them, but the reality is that our imaginations are not that good. Those who have lost a loved one to war can never forget the loss or the grief they feel. Grief has no timetable, and some pain just never goes away. No pain is more horrible than losing your child, and losing them in war, seriously compounds that pain.

Memorial Day, or Decoration Day as it was first called, started three years after the Civil War ended, on May 5,  1868. It was established by the head of an organization of Union veterans…the Grand Army of the Republic. Decoration Day was a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the war dead with flowers. Major General John A Logan declared that Decoration Day should be observed on May 30. It is believed that date was chosen because flowers would be in bloom all over the country. The first large observance was held that year at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. It was a day for all citizens to remember the sacrifice of the brave fallen heroes. And to let the families know that their fallen soldier would ever be forgotten. In honor of all the fallen, may you rest in peace. Thank you for your great sacrifice. Your nation is grateful.

1868. It was established by the head of an organization of Union veterans…the Grand Army of the Republic. Decoration Day was a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the war dead with flowers. Major General John A Logan declared that Decoration Day should be observed on May 30. It is believed that date was chosen because flowers would be in bloom all over the country. The first large observance was held that year at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. It was a day for all citizens to remember the sacrifice of the brave fallen heroes. And to let the families know that their fallen soldier would ever be forgotten. In honor of all the fallen, may you rest in peace. Thank you for your great sacrifice. Your nation is grateful.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

On December 7, 1941, Gillars was working in the studio when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was announced. She broke down in front of her colleagues and denounced their allies in the east. “I told them what I thought about Japan and that the Germans would soon find out about them,” she recalled. “The shock was terrific. I lost all discretion.” This may have been the the last time she had any self respect. She later said that she knew that her outburst could send her to a concentration camp, so faced with the prospect of joblessness or prison, the frightened Gillars produced a written oath of allegiance to Germany and returned to work. She sold out. Her duties were initially limited to announcing records and participating in chat shows, but treason is a slippery slope. Gillars’ broadcasts initially were largely apolitical, but that changed in 1942, when Max Otto Koischwitz, the program director in the USA Zone at the RRG, cast Gillars in a new show called Home Sweet Home. She soon acquired several names amongst her GI audience, including the Berlin Bitch, Berlin Babe, Olga, and Sally, but the one most common was “Axis Sally”. This name probably came when asked on air to describe herself, Gillars had said she was “the Irish type… a real Sally.”

As her broadcasts progressed, Gillars began doing a show called Home Sweet Home Hour. This show ran from December 24, 1942, until 1945. It was a regular propaganda program, the purpose of which was to make US forces in Europe feel homesick. A running theme of these broadcasts was the infidelity of soldiers’ wives and sweethearts while the listeners were stationed in Europe and North Africa. I’m was designed to promote depression. I guess her aversion to the ways of the Japanese and Germans wasn’t so strong after all. She also did a show called Midge-at-the-Mike, which broadcast from March to late fall 1943. I this program, she played American songs interspersed with defeatist propaganda, anti-Semitic rhetoric and attacks on Franklin D. Roosevelt. And she did the GI’s Letter-box and Medical Reports 1944, which was directed at the US home audience. In this show, Gillars used information on wounded and captured US airmen to cause fear and worry in their families. After D-Day, June 6, 1944, US soldiers wounded and captured in France were also reported on. Gillars and Koischwitz worked for a time from Chartres and Paris for this purpose, visiting hospitals and interviewing POWs. In 1943 they had toured POW camps in Germany, interviewing captured Americans and recording their messages for their families in the US. The interviews were then edited for broadcast as though the speakers were well-treated or sympathetic to the Nazi cause. Gillars made her most notorious broadcast on June 5, 1944, just prior to the D-Day invasion of Normandy, France, in a radio play written by Koischwitz, Vision Of Invasion. She played Evelyn, an Ohio mother, who dreams that her son had died a horrific death on a ship in the English Channel during an attempted invasion of Occupied Europe.

After the war, Gillars mingled with the people of Germany, until her capture. Gillars was indicted on September 10, 1948, and charged with ten counts of treason, but only eight were proceeded with at her trial, which began  on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.

on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.

When the United States was first trying to become a sovereign nation, due to the unfair treatment it received from its parent nation, Great Britain, King George III’s army tried to stop it in any way they could. I’m sure the king could see the possibilities this nation had, and I’m also sure he could see the writing on the wall concerning our independence. Still, the king said to fight, so fight they did. The people in the colonies thought the king’s rule was tyrannical and infringed on the colonists’ “rights as Englishmen”, and so they declared the colonies were going to be free and independent states. A war ensued, that we know as the Revolutionary War.

When the United States was first trying to become a sovereign nation, due to the unfair treatment it received from its parent nation, Great Britain, King George III’s army tried to stop it in any way they could. I’m sure the king could see the possibilities this nation had, and I’m also sure he could see the writing on the wall concerning our independence. Still, the king said to fight, so fight they did. The people in the colonies thought the king’s rule was tyrannical and infringed on the colonists’ “rights as Englishmen”, and so they declared the colonies were going to be free and independent states. A war ensued, that we know as the Revolutionary War.

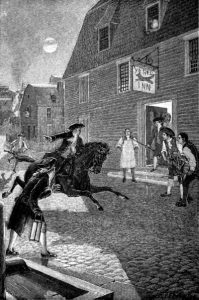

On April 7, 1775, British activity suggested the possibility of troop movements, and Dr Joseph Warren, an American physician who played a leading role in American Patriot organizations in Boston in the early days of the American Revolution, sent Paul Revere to warn the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, which was located in Concorde. This was also the site of one of the larger caches of Patriot military supplies. The warning spurred the residents into action…moving the military supplies away from the town. Just one week later, on April 14, General Gage received instructions from Secretary of State William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth. The orders had been dispatched on January 27. The British soldiers were told to disarm the rebels. It was known that they often hid weapons in Concord, as well as other locations. They were told to imprison the rebellion’s leaders, especially Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Dartmouth gave Gage considerable discretion in his commands. Gage issued orders to Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith to proceed from Boston “with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy… all Military stores…. But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants or hurt private property.” Gage did not issue written orders for the arrest of rebel leaders, because he was afraid that doing so might spark an uprising.

On the night of April 18, 1775, with tensions rising, Joseph Warren went to see Revere and William Dawes. He told them that the king’s troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge, as well as the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren’s intelligence suggested that the most likely objectives of the  regulars’ movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns. Prior to this time, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase “one if by land, two if by sea”, one lantern in the steeple would signal the army’s choice of the land route while two lanterns would signal the route “by water” across the Charles River. The British would ultimately take the water route, so two lanterns were placed in the steeple. Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north. Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route, many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army’s advance. Revere did not shout the phrase “The British are coming!” The success of his mission depended on secrecy, and the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and most of the Massachusetts colonists, who were predominantly English loyalists. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.” Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a ½ hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, spending a great deal of time discussing plans of action. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole purpose of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington. Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods. He eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, but fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride. After being roughly questioned for an hour or two, Revere was released when the patrol heard Minutemen alarm guns being fired on their approach to Lexington.

regulars’ movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns. Prior to this time, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase “one if by land, two if by sea”, one lantern in the steeple would signal the army’s choice of the land route while two lanterns would signal the route “by water” across the Charles River. The British would ultimately take the water route, so two lanterns were placed in the steeple. Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north. Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route, many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army’s advance. Revere did not shout the phrase “The British are coming!” The success of his mission depended on secrecy, and the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and most of the Massachusetts colonists, who were predominantly English loyalists. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.” Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a ½ hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, spending a great deal of time discussing plans of action. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole purpose of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington. Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods. He eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, but fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride. After being roughly questioned for an hour or two, Revere was released when the patrol heard Minutemen alarm guns being fired on their approach to Lexington.

About 5am on April 19, 700 British troops under Major John Pitcairn arrived at the town to find a 77 man strong colonial militia under Captain John Parker waiting for them on Lexington’s common green. Pitcairn ordered the outnumbered Patriots to disperse, and after a moment’s hesitation, the Americans began to drift off the green. Suddenly, the “shot heard around the world” was fired from an undetermined gun, and a cloud of musket smoke soon covered the green. When the brief Battle of Lexington ended, eight Americans lay dead and 10 others were wounded Only one British soldier was injured. The American Revolution had begun.

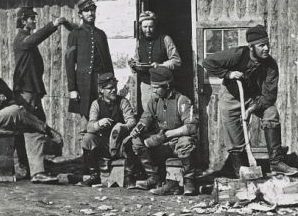

During the Civil War, the fighting was much different than these days…not just in the weapons used, but in a much bigger way. To send men out to battle in the winter was just too risky. Impassable, muddy roads and severe weather impeded active service in the wintertime. In fact, during the Civil War, the soldiers only spent a few days each year in actual combat. The rest of the time was spent getting from one battle to another, and wintering someplace because of bad weather. Even the rainy seasons caused problems, because rain brings muddy roads, and you can’t move heavy cannons on muddy roads. They get stuck. The soldiers tended to have a lot of time on their hands in the winter, and they couldn’t just go home either. In reality, disease caused more soldiers’ deaths than battle did.

During the Civil War, the fighting was much different than these days…not just in the weapons used, but in a much bigger way. To send men out to battle in the winter was just too risky. Impassable, muddy roads and severe weather impeded active service in the wintertime. In fact, during the Civil War, the soldiers only spent a few days each year in actual combat. The rest of the time was spent getting from one battle to another, and wintering someplace because of bad weather. Even the rainy seasons caused problems, because rain brings muddy roads, and you can’t move heavy cannons on muddy roads. They get stuck. The soldiers tended to have a lot of time on their hands in the winter, and they couldn’t just go home either. In reality, disease caused more soldiers’ deaths than battle did.

The soldiers sometimes kept journals of their time, which is where so much of the information we have about their time, came from. One such soldier was Elisha Hunt Rhodes. The winter months were monotonous for the soldiers. There was really nothing to do, but they needed to be kept in shape and at the ready, so the solution became days spent drilling. I’m sure that the boredom caused tempers to flair at times too, but the down time allowed the soldiers some time to bond and have a little bit of fun, as well. Nevertheless, the main objective for the winter months was to stay warm and busy, because their survival depended on it.

Rhodes was in the Army for four years, and he kept a journal for all of that time. He was a member of the 2nd Rhode Island Rhodes and fought in every battle from the First Bull Run to Appomattox. He rose from the rank of private to the rank of colonel in four years. According to Rhodes, the winter months were pretty quiet for the soldiers. They didn’t fight many battles, and so the months were spent drilling or smoking and sleeping. Some of the troops gambled and others drank or even visited the prostitutes who hung out around the camps. Believe it or not, the soldiers actually welcomed Picket Duty, which is when soldiers are posted on guard ahead of a main force. Pickets included about 40 or 50 men each. Several pickets would form a rough line in front of the main army’s camp. In case of enemy attack, the pickets usually would have time to warn the rest of the force. Picket Duty became a welcome break from the day to day monotony, because in Rhoades words, “One day is much like another at headquarters.”

Rhodes spent most of his winter months in or near Washington DC, giving him more diversions than some soldiers in the Civil War, who were in more remote locations. On one such trip into town came on February 26, 1862, he took the opportunity to hear Senator Henry Wilson from Massachusetts speak on expelling disloyal members of Congress. After listening to the speech, Rhodes and his friend Isaac Cooper attended a fair at a

Methodist church and met two young women, who the soldiers escorted home. Like other soldiers, Rhodes welcomed the departure from winter quarters and an end to the monotony. “Our turn has come,” he wrote when his unit began moving south to Richmond, Virginia,in 1864. His winter break was over, and he would find himself back in battle again. Rhodes would survive the Civil War and after a long life, passed away on January 14, 1917 at 75.

Methodist church and met two young women, who the soldiers escorted home. Like other soldiers, Rhodes welcomed the departure from winter quarters and an end to the monotony. “Our turn has come,” he wrote when his unit began moving south to Richmond, Virginia,in 1864. His winter break was over, and he would find himself back in battle again. Rhodes would survive the Civil War and after a long life, passed away on January 14, 1917 at 75.