soldiers

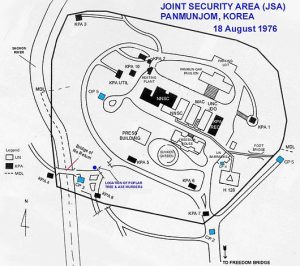

After the August 18, 1976 ace murder of two United States Army officers, Captain Arthur Bonifas and Lieutenant Mark Barrett, by North Korean soldiers, in the Joint Security Area located in the North Korean Demilitarized Zone, it was decided that something had to be done about a certain poplar tree that blocked the view of UN observers, allowing them to be assaulted and killed by the North Koreans, who claimed that the tree had been planted by Kim Il-Sung. It was dubbed the Panmunjom axe murder incident, and it was infuriating to the United States.

After the August 18, 1976 ace murder of two United States Army officers, Captain Arthur Bonifas and Lieutenant Mark Barrett, by North Korean soldiers, in the Joint Security Area located in the North Korean Demilitarized Zone, it was decided that something had to be done about a certain poplar tree that blocked the view of UN observers, allowing them to be assaulted and killed by the North Koreans, who claimed that the tree had been planted by Kim Il-Sung. It was dubbed the Panmunjom axe murder incident, and it was infuriating to the United States.

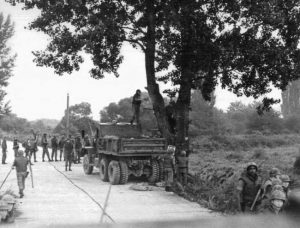

Three days later, American and South Korean forces launched Operation Paul Bunyan. There was one objective to Operation Paul Bunyan…cut down the tree with a show of force to intimidate North Korea into backing down. Operation Paul Bunyan was carried out on August 21 at 07:00, three days after the killings. A convoy of 23 American and South Korean vehicles, known as “Task Force Vierra”, named after Lieutenant Colonel Victor Vierra, commander of the United States Army Support Group, drove into the JSA without any warning to the North Koreans. There was just one observation post manned at that hour. The vehicles contained two eight-man teams of military engineers from the 2nd Engineer Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division, equipped with chain-saws to cut down the tree. Accompanying these teams were two 30-man security platoons from the Joint Security Force, who were armed with pistols and axe handles. The 1st Platoon secured the northern entrance to the JSA via the Bridge of No Return, while the 2nd Platoon secured the southern edge of the area. A team from B Company, commanded by Captain Walter Seifried, activated the detonation systems for the charges on Freedom Bridge and had the 165mm main gun of the M728 combat engineer vehicle aimed mid-span to ensure that the bridge would fall should the order be given for its destruction.

B Company, supporting E Company (bridge), were building M4T6 rafts on the Imjin River should the situation require emergency evacuation by that route. An additional 64-man task force of the South Korean Special Forces accompanied them, armed with clubs and trained in Tae Kwon Do, supposedly without firearms. Once  they parked their trucks near the Bridge of No Return, however, they started throwing out the sandbags that lined the truck bottoms, and handing out M16 rifles and M79 grenade launchers that had been concealed below. Several of the commandos also had M18 Claymore mines strapped to their chests with the firing mechanism in their hands, and were shouting at the North Koreans to cross the bridge. A U.S. Infantry company in 20 utility helicopters and seven Cobra attack helicopters circled behind them. Behind these helicopters, B-52 Stratofortresses, came from Guam escorted by US F-4 Phantom IIs from Kunsan Air Base and South Korean F-5 and F-86 fighters were visible flying across the sky at high altitude. At Taegu Air Base, F-111 bombers of the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing out of Mountain Home Air Force Base, were stationed, and F-4 Phantoms C and D from the 18th TFW Kadena Air Base and Clark Air Base were also deployed. The aircraft carrier USS Midway task force had also been moved to a station just offshore. Near the edges of the DMZ, many more heavily armed U.S. and South Korean infantry, artillery including the Second Battalion, 71st Air Defense Regiment armed with Improved Hawk missiles, and armor were waiting to back up the special operations team. Bases near the DMZ were prepared for demolition in case of a military response. The defense condition (DEFCON) was elevated on order of General Stilwell, as recounted in Colonel De LaTeur’s research paper later. 12,000 additional troops were ordered to Korea, including 1,800 Marines from Okinawa. During the operation, nuclear-capable strategic bombers circled over the JSA. According to an intelligence analyst monitoring the North Korea tactical radio net, the accumulation of force “blew their… minds.” Altogether, Task Force Vierra consisted of 813 men: almost all of the men of the United States Army Support Group, of which the Joint Security Force was a part; a South Korean reconnaissance company; a South Korean Special Forces company which had infiltrated the river area by the bridge the night before; and members of a reinforced composite rifle company from the 9th Infantry Regiment. In addition to this force, every UNC force in the rest of South Korea was on battle alert.

they parked their trucks near the Bridge of No Return, however, they started throwing out the sandbags that lined the truck bottoms, and handing out M16 rifles and M79 grenade launchers that had been concealed below. Several of the commandos also had M18 Claymore mines strapped to their chests with the firing mechanism in their hands, and were shouting at the North Koreans to cross the bridge. A U.S. Infantry company in 20 utility helicopters and seven Cobra attack helicopters circled behind them. Behind these helicopters, B-52 Stratofortresses, came from Guam escorted by US F-4 Phantom IIs from Kunsan Air Base and South Korean F-5 and F-86 fighters were visible flying across the sky at high altitude. At Taegu Air Base, F-111 bombers of the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing out of Mountain Home Air Force Base, were stationed, and F-4 Phantoms C and D from the 18th TFW Kadena Air Base and Clark Air Base were also deployed. The aircraft carrier USS Midway task force had also been moved to a station just offshore. Near the edges of the DMZ, many more heavily armed U.S. and South Korean infantry, artillery including the Second Battalion, 71st Air Defense Regiment armed with Improved Hawk missiles, and armor were waiting to back up the special operations team. Bases near the DMZ were prepared for demolition in case of a military response. The defense condition (DEFCON) was elevated on order of General Stilwell, as recounted in Colonel De LaTeur’s research paper later. 12,000 additional troops were ordered to Korea, including 1,800 Marines from Okinawa. During the operation, nuclear-capable strategic bombers circled over the JSA. According to an intelligence analyst monitoring the North Korea tactical radio net, the accumulation of force “blew their… minds.” Altogether, Task Force Vierra consisted of 813 men: almost all of the men of the United States Army Support Group, of which the Joint Security Force was a part; a South Korean reconnaissance company; a South Korean Special Forces company which had infiltrated the river area by the bridge the night before; and members of a reinforced composite rifle company from the 9th Infantry Regiment. In addition to this force, every UNC force in the rest of South Korea was on battle alert.

All this to cut down one tree!! My first thought on all this was…overkill, to the extreme!! That’s what I thought at first, but after researching the operation more, I realized that this was as much a show of force, as it was a way to cut down a tree that was really blocking a view that was necessary for keeping soldiers safe. North Korea needed to be shown what could come of such an attack, should it ever happen again. And it worked…North Korea accepted responsibility for the earlier killings. The incident is also known alternatively as the hatchet incident, the poplar tree incident, and the tree trimming incident. Final loss of life, two American Army officers, and one poplar tree.

When we think of wartime atrocities, most of us think of the Holocaust, and that was indeed a horrible atrocity. Nevertheless, there have been a number of horrible dictators in history, and most of them committed some kind of atrocity. One of the worst atrocities in history, is one that very few people even know about. Most people have heard about the horrible experiments the Nazis performed on humans. The Nazi doctor, Joseph Mengele headed up that torture practice. But the Nazis weren’t alone in conducting cruel experiments on humans. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Unit 731. Some of the details of this unit’s activities are still uncovered. I don’t understand how anyone could have such little regard for human life, as to conduct some of the horrible experiments n them that some of these dictators and their cohorts did.

When we think of wartime atrocities, most of us think of the Holocaust, and that was indeed a horrible atrocity. Nevertheless, there have been a number of horrible dictators in history, and most of them committed some kind of atrocity. One of the worst atrocities in history, is one that very few people even know about. Most people have heard about the horrible experiments the Nazis performed on humans. The Nazi doctor, Joseph Mengele headed up that torture practice. But the Nazis weren’t alone in conducting cruel experiments on humans. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Unit 731. Some of the details of this unit’s activities are still uncovered. I don’t understand how anyone could have such little regard for human life, as to conduct some of the horrible experiments n them that some of these dictators and their cohorts did.

For 40 years, the horrific activities of “Unit 731” remained one the most closely guarded secrets of World War II. It was not until 1984 that Japan acknowledged what it had done and long denied. The vile experiments on humans conducted by the unit in preparation for germ warfare were atrocious. The Japanese doctors deliberately infected people with plague, anthrax, cholera and other pathogens. It is estimated that as many as 3,000 enemy soldiers and civilians were used as guinea pigs. Some of the more horrific experiments included surgery without anesthesia to see how the human body handled pain, and pressure chambers to see how much pressure a human could take before his eyes popped out.

The compound for Unit 731 was set up in 1938 in Japanese-occupied China with the aim of developing biological weapons. It also operated a secret research and experimental school in Shinjuku, central Tokyo. Its  head was Lieutenant Shiro Ishii. Japanese universities and medical schools also supported the unit, by supplying doctors and research staff. I can’t imagine being assigned to such a facility. The picture now emerging about Unit 731’s activities is horrifying. According to reports, which were never officially admitted by the Japanese authorities, the unit used thousands of Chinese and other Asian civilians and wartime prisoners as human guinea pigs to breed and develop killer diseases. Many of the prisoners, who were murdered in the name of research, were used in hideous vivisection and other medical experiments, including barbaric trials to determine the effect of frostbite on the human body. To ease the conscience of those involved, if that is even possible, the prisoners were referred to not as people or patients, but as “Maruta”, which means wooden logs. I suppose they thought it would help, but I doubt if it did.

head was Lieutenant Shiro Ishii. Japanese universities and medical schools also supported the unit, by supplying doctors and research staff. I can’t imagine being assigned to such a facility. The picture now emerging about Unit 731’s activities is horrifying. According to reports, which were never officially admitted by the Japanese authorities, the unit used thousands of Chinese and other Asian civilians and wartime prisoners as human guinea pigs to breed and develop killer diseases. Many of the prisoners, who were murdered in the name of research, were used in hideous vivisection and other medical experiments, including barbaric trials to determine the effect of frostbite on the human body. To ease the conscience of those involved, if that is even possible, the prisoners were referred to not as people or patients, but as “Maruta”, which means wooden logs. I suppose they thought it would help, but I doubt if it did.

Before Japan’s surrender, the site of the experiments was completely destroyed, so that no evidence is left. I don’t suppose we would have known anything had it not been for the pictures that have surfaced, and people who have told the story later. After the site was destroyed, the remaining 400 prisoners were shot and the employees of the unit had to swear secrecy, or risk their own death. The mice kept in the laboratory were then  released, which most likely cost the lives of as many as 30,000 people, because the mice were infected with the Bubonic Plague, and they spread the disease. Few of those involved with Unit 731 have admitted their guilt. Some were caught in China at the end of the war, were arrested and detained, but only a handful of them were prosecuted for war crimes. In Japan, not one was brought to justice. In a secret deal, the post-war American administration gave them immunity for prosecution in return for details of their experiments. Some of the worst criminals, including Hisato Yoshimura, who was in charge of the frostbite experiments, went on to occupy key medical and other posts in public and private sectors…their guilty feelings, if they had any, existed only in their own minds.

released, which most likely cost the lives of as many as 30,000 people, because the mice were infected with the Bubonic Plague, and they spread the disease. Few of those involved with Unit 731 have admitted their guilt. Some were caught in China at the end of the war, were arrested and detained, but only a handful of them were prosecuted for war crimes. In Japan, not one was brought to justice. In a secret deal, the post-war American administration gave them immunity for prosecution in return for details of their experiments. Some of the worst criminals, including Hisato Yoshimura, who was in charge of the frostbite experiments, went on to occupy key medical and other posts in public and private sectors…their guilty feelings, if they had any, existed only in their own minds.

It has been 74 years since 17,740 Americans gave their lives to liberate the people of the Netherlands (often called Holland) from the Germans during World War II, and the people of Holland have never forgotten that sacrifice. For 74 years now, the people of the small village of Margraten, Netherlands have taken care of the graves of the lost at the Margraten American Cemetery. On Memorial Day, they come, every year, bringing Memorial Day bouquets for men and women they never knew, but whose 8,300 headstones the people of the Netherlands have adopted as their own. Of the 17,740 who were originally buried there, 9,440 were later moved to various paces in he United States by their families. “What would cause a nation recovering from losses and trauma of their own to adopt the sons and daughters of another nation?” asked Chotin, the only American descendant to speak on that Sunday 4 years ago. “And what would keep that commitment alive for all of these years, when the memory of that war has begun to fade? It is a unique occurrence in the history of civilization.”

It has been 74 years since 17,740 Americans gave their lives to liberate the people of the Netherlands (often called Holland) from the Germans during World War II, and the people of Holland have never forgotten that sacrifice. For 74 years now, the people of the small village of Margraten, Netherlands have taken care of the graves of the lost at the Margraten American Cemetery. On Memorial Day, they come, every year, bringing Memorial Day bouquets for men and women they never knew, but whose 8,300 headstones the people of the Netherlands have adopted as their own. Of the 17,740 who were originally buried there, 9,440 were later moved to various paces in he United States by their families. “What would cause a nation recovering from losses and trauma of their own to adopt the sons and daughters of another nation?” asked Chotin, the only American descendant to speak on that Sunday 4 years ago. “And what would keep that commitment alive for all of these years, when the memory of that war has begun to fade? It is a unique occurrence in the history of civilization.”

The people of Margraten immediately embraced the Americans, who had come to their aid when they needed it most. The town’s mayor invited the company’s commanders to sleep in his home, while the enlisted men slept in the schools. The protection against rain and buzz bombs was welcomed. Later, villagers hosted U.S. troops when the men were given rest-and-recuperation breaks from trying to breach the German frontier defenses, known as the Siegfried Line. “After four dark years of occupation, suddenly [the Dutch] people were free from the Nazis, and they could go back to their normal lives and enjoy all the freedoms they were used to. They knew they had to thank the American allies for that,” explained Frenk Lahaye, an associate at the cemetery.

By November 1944, two months after the village’s 1,500 residents had been freed from Nazi occupation by the U.S. 30th Infantry Division the town’s people were filled with gratitude, but the war wasn’t over. In late 1944  and early 1945, thousands of American soldiers would be killed in nearby battles trying to pierce the German defense lines. The area was filled with Booby-traps and heavy artillery fire. All that combined with a ferocious winter, dealt major setbacks to the Allies, who had already suffered losses trying to capture strategic Dutch bridges crossing into Germany during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden.

and early 1945, thousands of American soldiers would be killed in nearby battles trying to pierce the German defense lines. The area was filled with Booby-traps and heavy artillery fire. All that combined with a ferocious winter, dealt major setbacks to the Allies, who had already suffered losses trying to capture strategic Dutch bridges crossing into Germany during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden.

Now, the U.S. military needed a place to bury its fallen. The Americans ultimately picked a fruit orchard just outside Margraten. On the first day of digging, the sight of so many bodies made the men in the 611th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company ill. The bodies arrived in a procession of trucks and trailers. Death hung in the air over the whole village of Margraten. The sight of so much death caused a few of the people helping with the burials to become ill. They suddenly made a break for the latrines. The first burial at Margraten took place on November 10, 1944. Laid to rest in Plot A, Row 1, Grave 1: John David Singer Jr, a 25-year-old infantryman, whose remains would later be repatriated and buried in Denton, Maryland, about 72 miles east of Washington. Between late 1944 and spring 1945, up to 500 bodies arrived each day, so many that the mayor went door to door asking villagers for help with the digging. Over the next two years, about 17,740 American soldiers would be buried here, though the number of graves would shrink as thousands of families asked for their loved ones’ remains to be sent home, until 8,300 remained, and still, the graves are cared for by the town’s people, as if the dead were their own loved one. Not only that, but they have taken it upon themselves to research the deceased, and learn of their lives as a way of showing honor to these fallen heroes.

On May 29, 1945, the day before the cemetery’s first Memorial Day commemoration, 20 trucks from the 611th  collected flowers from 60 different Dutch villages. Nearly 200 Dutch men, women and children spent all night arranging flowers and wreaths by the dirt-covered graves, which bore makeshift wooden crosses and Stars of David. By 8am, the road leading into Margraten was jammed with Dutch people coming on foot, bicycle, carriages, horseback and by car. Silent film footage shot that day shows some of the men wearing top hats as they carried wreaths. A nun and two young girls laid flowers at a grave, then prayed. Solemn-faced children watched as cannons blasted salutes. The Dutch, Shomon wrote, “were perceptibly stirred, wept in bowed reverence.” All they do for these heroes is because they have vowed never to forget.

collected flowers from 60 different Dutch villages. Nearly 200 Dutch men, women and children spent all night arranging flowers and wreaths by the dirt-covered graves, which bore makeshift wooden crosses and Stars of David. By 8am, the road leading into Margraten was jammed with Dutch people coming on foot, bicycle, carriages, horseback and by car. Silent film footage shot that day shows some of the men wearing top hats as they carried wreaths. A nun and two young girls laid flowers at a grave, then prayed. Solemn-faced children watched as cannons blasted salutes. The Dutch, Shomon wrote, “were perceptibly stirred, wept in bowed reverence.” All they do for these heroes is because they have vowed never to forget.

A while back, while looking at historical pictures, I came across one that bore an amazing resemblance to my grandson, Chris Petersen. I realize that a lot of people say that some people remind them of other people, but even my family agreed that this young man looked like Chris at that age. I have no idea who this boy is, or if he is related to Chris, because the picture doesn’t tell his name…just his occupation, which was quite interesting. The boy is, what is known as, a Powder Monkey. I had no idea what that was, and after doing some research on it, I’m thankful that powder monkey is not an occupation we have today, and thankful that my grandson never had the opportunity to be one. To me, it seems like a very dangerous occupation.

A while back, while looking at historical pictures, I came across one that bore an amazing resemblance to my grandson, Chris Petersen. I realize that a lot of people say that some people remind them of other people, but even my family agreed that this young man looked like Chris at that age. I have no idea who this boy is, or if he is related to Chris, because the picture doesn’t tell his name…just his occupation, which was quite interesting. The boy is, what is known as, a Powder Monkey. I had no idea what that was, and after doing some research on it, I’m thankful that powder monkey is not an occupation we have today, and thankful that my grandson never had the opportunity to be one. To me, it seems like a very dangerous occupation.

Powder boys were used during the 17th century on warships. A powder boy or “powder monkey” manned naval artillery guns as a member of a warship’s crew, primarily during the age of sailboats. His chief role was to carry gunpowder from the powder magazine in the ship’s hold to the artillery guns. Sometimes he carried bulk powder and other times he carried cartridges, to minimize the risk of fires and explosions. The function was usually fulfilled by boy seamen of 12 to 14 years of age. Powder monkeys were selected for the job for their speed and height. They needed to be short so they could not be seen, and could move more easily in the limited space between decks, while remaining hidden behind the ship’s gunwale, thereby keeping them from being shot by enemy ships’ sharp shooters. Some women and older men also worked as powder monkeys. I realize that this might have seemed like a good idea, but as a mom and grandma, I would be terribly worried if that were my boy on one of those ships.

While the Royal Navy first began using the term “powder monkey” in the 17th century, it was later used, and  continues to be used in some countries, to signify a skilled technician or engineer who engages in blasting work, such as in the mining or demolition industries. In such industries, a “powder monkey” is also sometimes referred to as a “blaster.” It seems that just about any occupation that carries the name “powder monkey” is a dangerous one. As to the boys who did this work on warships, well…their bravery is amazing. They must have see death around them. They knew the risks. Still, they saw a need, and knew that their contribution would help their country. They were patriots, and as with any soldier, they have my respect. They should never be forgotten, because they were soldiers too…in every way.

continues to be used in some countries, to signify a skilled technician or engineer who engages in blasting work, such as in the mining or demolition industries. In such industries, a “powder monkey” is also sometimes referred to as a “blaster.” It seems that just about any occupation that carries the name “powder monkey” is a dangerous one. As to the boys who did this work on warships, well…their bravery is amazing. They must have see death around them. They knew the risks. Still, they saw a need, and knew that their contribution would help their country. They were patriots, and as with any soldier, they have my respect. They should never be forgotten, because they were soldiers too…in every way.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli Campaign was Australia’s and New Zealand’s introduction to the Great War. Many Australians and New Zealanders fought on the Peninsula from the day of the landings (April 25, 1915) until the evacuation on December 20, 1915. The 25th April is the New Zealand equivalent of Armistice Day and is marked as the ANZAC day in both countries with Dawn Parades and  other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

While many losses came out of this campaign, it seems that there were two who were saved…potentially anyway. After the campaign was over, and people were wandering the area, someone came across an unusual, and seriously rare, find. There on the ground were two bullets that had collided with each other in mid-air, thus saving the lives of the two combatants who fired the rounds. Obviously, they could have been hit by another round, in which case the mid-air collision only slightly prolonged their lives. At least this scenario might be what you would think. The reality is that you would be wrong. Taking a look closer at the bullets, it is quite obvious that one round collided with  another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

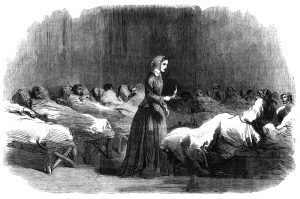

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

That day, a public notice appeared in local papers recognizing the sacrifice of women to the cause of the revolution. The notice urged others to recognize women’s contributions as well, and announced, “The necessity of taking all imaginable care of those who may happen to be wounded in the country’s cause, urges us to address our humane ladies, to lend us their kind assistance in furnishing us with linen rags and old sheeting, for bandages.” On and off the battlefield, women were known to support the revolutionary cause by providing nursing assistance. But donating bandages and sometimes applying them was only one form of aid provided by the women of the new United States. From the earliest protests against British taxation, women’s assent and labor  was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

Tea and cloth are perhaps the best examples of these boycotted products. While most schoolchildren have read of the men who dressed as Mohawk Indians and dumped large volumes of tea into Boston Harbor at the Boston Tea Party, as a form of opposition to the hated Tea Act, few realize that women…not men…drank most of the tea in colonial America. Samuel Adams and his friends may have dumped the tea in the harbor, but they were far more likely to drink rum than tea when they returned to their homes. Conveniently, their actions actually deprived their wives, mothers, sisters and daughters, and not themselves. The colonists only resorted to an attempted boycott of rum in 1774, after Britain had closed the port of Boston. I guess it was time for drastic measures.

Similarly, when John Adams and other men in power thought it best to stop importing fine British fabrics with  which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

It’s amazing how much we can fear the things we don’t understand. As an example, the Indians who lived around the geysers of Yellowstone. The early Indians thought that the hissing and thundering were the voices of evil spirits. Even though the geysers were frightening, the Indians regarded the mountains at the head of the river as the crest of the world, and the man who gained their summits could see the happy hunting-grounds below, brightened with the homes of the blessed. They loved this land in which their fathers had hunted, and when they were driven back from the settlements the Crows took refuge in what is now Yellowstone Park, but they were still not safe.

It’s amazing how much we can fear the things we don’t understand. As an example, the Indians who lived around the geysers of Yellowstone. The early Indians thought that the hissing and thundering were the voices of evil spirits. Even though the geysers were frightening, the Indians regarded the mountains at the head of the river as the crest of the world, and the man who gained their summits could see the happy hunting-grounds below, brightened with the homes of the blessed. They loved this land in which their fathers had hunted, and when they were driven back from the settlements the Crows took refuge in what is now Yellowstone Park, but they were still not safe.

The soldiers pursued them, intent on avenging acts that the red men had committed while they were being so wrongly mistreated. A small group of the original fugitive band gathered at the head of that mighty rift in the earth known as the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone…a group that had succeeded in escaping the bullets of the soldiers, and with great courage they resolved to die rather than be taken and carried away to be held in a distant prison. They built a raft and laced it on the river at the foot of the upper fall, and for a few days they  enjoyed the plenty and peace that were their privilege in former times. A short-lived peace, however, for one morning they are awakened by the rifle fire, and they knew that the troops are upon them.

enjoyed the plenty and peace that were their privilege in former times. A short-lived peace, however, for one morning they are awakened by the rifle fire, and they knew that the troops are upon them.

Boarding their raft they thrust it toward the middle of the stream, perhaps with the idea of making it to the opposite shore. If that was their intent, the rapid current kept them from attaining their goal. A few among them had guns, but their bullets had only a slight effect at the troops, who stood watching in amazement from the shore. The soldiers didn’t fire, but watched, with something like dread, the descent of the raft as it passes into the current. Then, with many a turn and pitch, it whirled on faster and faster. The death-song rises triumphant above the lash of the waves and that distant but awful booming that is to be heard in the  canyon. Every red man has his face turned toward the foe with a look of defiance, and the tones of the death-chant have in them something of mockery and hate. The Indians went defiantly to their deaths, refusing to show the slightest amount of fear.

canyon. Every red man has his face turned toward the foe with a look of defiance, and the tones of the death-chant have in them something of mockery and hate. The Indians went defiantly to their deaths, refusing to show the slightest amount of fear.

The raft was now between the jaws of the rocks. Beyond and below are vast walls, shelving toward the floor of the gulf a thousand feet below. The beauty of the falls will be their last vision…brilliant colors shining in the sun of morning that sheds as peaceful a light on wood and hill. They believe they are heading to a place where humans don’t shoot human, and where they will be free again. The raft was galloping through the foam like a racehorse, and even the hardened soldiers could not hold back the shudder as they imagined the fate of the brave Indians. Now the brink is reached. The raft tips toward the gulf, and with a cry of triumph the red men are launched over the cataract, into the bellowing chasm, and the rocky floor that waited below.

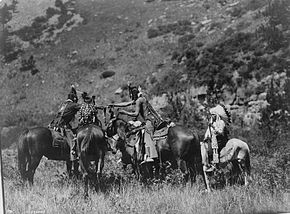

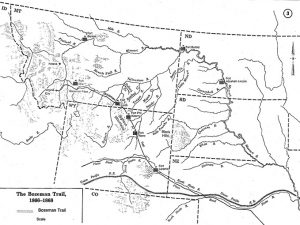

The move west to settle America was seldom a peaceful move. These days we think of loading up our car, and moving to a new city…done and easy, but it wasn’t so back then. There were outlaws, Indians, and unknown perils that could end a trip west, almost before it got started. There were a number of trails commonly used to get to the gold fields in the west, but the Bozeman Trail was one of the most violent, quarrelsome, and ultimately failed experiments in American frontier history. The trail was named for John Bozeman, an emigrant from Georgia, who was said to have blazed the route, but in actuality, the Indians had been using the route as a travel corridor for centuries. Nevertheless, John Bozeman did play a part in the trail. In 1863, Bozeman and partner, John Jacobs widened this corridor for use as a wagon road. They were following in much the same footsteps as Captain William Raynolds had four years earlier in a mapping and exploration expedition for the Army Corps of Topographic Engineers. The plan was to make the trail a shortcut to the goldfields in and around Virginia City, Montana territory. The Bozeman route split off of the Oregon Trail in central Wyoming. Then it skirted the Bighorn Mountains, crossed several rivers including the Bighorn, then traversed mountainous terrain into western Montana. The trail follows a very similar route to the current roads that meander through Wyoming today. The Bozeman trail had several advantages, including an abundant supply of water along with the most direct route to the goldfields, making it the go to trail of that era.

The move west to settle America was seldom a peaceful move. These days we think of loading up our car, and moving to a new city…done and easy, but it wasn’t so back then. There were outlaws, Indians, and unknown perils that could end a trip west, almost before it got started. There were a number of trails commonly used to get to the gold fields in the west, but the Bozeman Trail was one of the most violent, quarrelsome, and ultimately failed experiments in American frontier history. The trail was named for John Bozeman, an emigrant from Georgia, who was said to have blazed the route, but in actuality, the Indians had been using the route as a travel corridor for centuries. Nevertheless, John Bozeman did play a part in the trail. In 1863, Bozeman and partner, John Jacobs widened this corridor for use as a wagon road. They were following in much the same footsteps as Captain William Raynolds had four years earlier in a mapping and exploration expedition for the Army Corps of Topographic Engineers. The plan was to make the trail a shortcut to the goldfields in and around Virginia City, Montana territory. The Bozeman route split off of the Oregon Trail in central Wyoming. Then it skirted the Bighorn Mountains, crossed several rivers including the Bighorn, then traversed mountainous terrain into western Montana. The trail follows a very similar route to the current roads that meander through Wyoming today. The Bozeman trail had several advantages, including an abundant supply of water along with the most direct route to the goldfields, making it the go to trail of that era.

Still, the trail had one major drawback. It cut through the heart of territory that had been promised to several Indian tribes by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1848, making the people traveling the trail…the outlaws. The area included the rich hunting grounds of the Powder River Country, claimed by the Sioux and other tribes. They were not feeling very hospitable about these “white men” traipsing through their hunting grounds, killing their animals, and running off many in the herds. Nevertheless, the first emigrant trains began traveling up the trail not long after Bozeman and Jacobs had finished marking the route. In 1864, a large train of 2,000 settlers  successfully made the trek. This was the high point of travel along the corridor. Though some wagon trains were successful after that, there were constant threats of attack. Over the next two years travel along the corridor came to a complete halt because of numerous raids by a coalition of tribes.

successfully made the trek. This was the high point of travel along the corridor. Though some wagon trains were successful after that, there were constant threats of attack. Over the next two years travel along the corridor came to a complete halt because of numerous raids by a coalition of tribes.

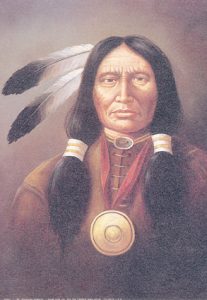

Then the people started to put pressure on the United States government to protect the travelers. In 1866, United States Army troops were dispatched to construct three forts along the trail, which would supposedly offer protection to wagon trains. These posts, running from south to north, were Forts Reno, Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith. Ominously, each of these forts was named after a general that had died during the just completed Civil War. Somehow that doesn’t seem to instill a lot of hope…at least to me. With the installation of the forts, the trail had, in effect become a military road. The protection afforded by the United States Army presence enraged the tribes. With that intervention came a two year conflict, known as Red Cloud’s War. Under the leadership of Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud, raids and ambushes were carried out against soldiers, civilians, supply trains and anyone else who dared to attempt the trail.

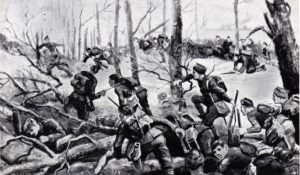

Three famous skirmishes were The Fetterman Massacre, in December, 1866, in which an army detachment of 79 soldiers and 2 civilians led by Captain William Fetterman were lured from Fort Phil Kearney and ambushed within a few miles of the fort. On August 1, 1867, the Hayfield Fight, where 19 soldiers and 6 civilians detailed for guard and hay cutting duty were attacked. The Indians held them under siege for over 8 hours, but they managed to hold off 500 hundred warriors until help arrived. And finally, The Wagon Box Fight, where a detachment of 31 soldiers sent out to guard a team of wood cutters, was encircled. They fought off numerous attacks over a five hour period from hundreds of warriors. These continued raids and skirmishes were the rule that proved that peace was not going to be the reality they had hoped. Life guarding the trail was a  combination of tension, monotony, and loneliness. Soldiers on the verge of mutiny and even cases of insanity, deserted their posts. With few, if any, emigrants using the trail, because they were too afraid, the army sequestered behind fortress walls and tribes showing few signs of easing up on attacks. Finally, the United States government decided to pursue a peace policy. The second (1868) Fort Laramie Treaty recognized the Powder River Country once again as the hunting territory of the Lakota and their allies. A presidential proclamation was issued to abandon the forts. The Bozeman Trail was history, and for the first time, the United States government had lost a war. What a shock that must have been for our nation.

combination of tension, monotony, and loneliness. Soldiers on the verge of mutiny and even cases of insanity, deserted their posts. With few, if any, emigrants using the trail, because they were too afraid, the army sequestered behind fortress walls and tribes showing few signs of easing up on attacks. Finally, the United States government decided to pursue a peace policy. The second (1868) Fort Laramie Treaty recognized the Powder River Country once again as the hunting territory of the Lakota and their allies. A presidential proclamation was issued to abandon the forts. The Bozeman Trail was history, and for the first time, the United States government had lost a war. What a shock that must have been for our nation.

On this day, January 22, 1879, American soldiers were in pursuit of Cheyenne Chief Dull Knife and his people, who were making a desperate bid for freedom. The ensuing battle was a horrific defeat for Chief Dull Knife and his band. The soldiers effectively crushed the so-called Dull Knife Outbreak.

On this day, January 22, 1879, American soldiers were in pursuit of Cheyenne Chief Dull Knife and his people, who were making a desperate bid for freedom. The ensuing battle was a horrific defeat for Chief Dull Knife and his band. The soldiers effectively crushed the so-called Dull Knife Outbreak.

Dull Knife was a leading chief of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, and was sometimes called Morning Star. He had long urged peace with the powerful Anglo-Americans invading his homeland in the Powder River country of modern-day Wyoming and Montana. However, the 1864 massacre of more than 200 peaceful Cheyenne Indians by Colorado militiamen at Sand Creek, Colorado, led Dull Knife to question whether the Anglo-Americans could ever be trusted. He reluctantly led his people into a war he suspected they could never win. In 1876, many of Dull Knife’s people fought along side Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull at their victorious battle at Little Bighorn, but Chief Dull Knife did not participate.

During the winter after Little Bighorn, Dull Knife and his people camped along the headwaters of the Powder River in Wyoming. It was here that they fell victim to the army’s winter campaign for revenge. In November, General Ranald Mackenzie’s expeditionary force discovered the village and attacked. Dull Knife lost many of his people, and along with several other Indian leaders, reluctantly surrendered the following spring. In 1877, the  military relocated Dull Knife and his followers far away from their Wyoming homeland to the large Indian Territory on the southern plains, in what is now Kansas and Oklahoma. They were not allowed to practice their traditional hunts, the band was largely dependent on meager government provisions. Beset by hunger, homesickness, and disease, Dull Knife and his people rebelled after one year. In September 1878, they joined another band to make an epic march back to their Wyoming homeland. Although Dull Knife publicly announced his peaceful intentions, the government regarded the fleeing Indians as renegades, and soldiers from bases scattered throughout the Plains attacked the Indians in an unsuccessful effort to turn them back.

military relocated Dull Knife and his followers far away from their Wyoming homeland to the large Indian Territory on the southern plains, in what is now Kansas and Oklahoma. They were not allowed to practice their traditional hunts, the band was largely dependent on meager government provisions. Beset by hunger, homesickness, and disease, Dull Knife and his people rebelled after one year. In September 1878, they joined another band to make an epic march back to their Wyoming homeland. Although Dull Knife publicly announced his peaceful intentions, the government regarded the fleeing Indians as renegades, and soldiers from bases scattered throughout the Plains attacked the Indians in an unsuccessful effort to turn them back.

Arriving at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, near their Wyoming homeland, Dull Knife and his people surrendered to the government in the hopes they would be allowed to stay in the territory, but that was not to be an option. Administrators instead threatened to hold the band captive at Fort Robinson until they would agree to return south to the Indian Territory. Unwilling to give up when his goal was so close, in early January, Dull Knife led about 100 of his people in one final desperate break for freedom. Soldiers from Fort Robinson chased after the already weak and starving band of men, women, and children, and on January 22, they attacked and killed at  least 30 people, including several in the immediate family of Dull Knife.

least 30 people, including several in the immediate family of Dull Knife.

Badly bloodied, most of the survivors returned to Fort Robinson and accepted their fate. Dull Knife managed to escape, and he eventually found shelter with Chief Red Cloud on the Sioux reservation in Nebraska. Permitted to remain on the reservation, Dull Knife died four years later, deeply bitter towards the White Man he had once hoped to live with peacefully. The same year, the government finally allowed the Northern Cheyenne to move to a permanent reservation on the Tongue River in Montana near their traditional homeland. At last, Dull Knife’s people had come home, but their great chief didn’t live to join them.

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

The Battle of Loos, which took place in September 1915, resulted in devastating casualties for the Allies and was taken by the British as a sign of the need to change their conduct of the war. In one major consequence, Sir John French was replaced by Sir Douglas Haig as British commander in the wake of that battle. “Tom spoke very well,” Churchill wrote to his wife, Clementine, “but his tale was one of hopeless failure, of sublime heroism utterly wasted and of splendid Scottish soldiers shorn away in vain with never the ghost of a chance of success. Afterwards they asked me what was the lesson of the lecture. I restrained an impulse to reply ‘Don’t do it again.’ But they will–I have no doubt.” What Churchill took away from the lecture was that in war, there is no winner…not really. There are losses on both sides, sometimes almost equal in number, so that the victory goes to the one who holds out the longest. Defeat comes in surrender.

Churchill had been demoted from First Lord of the Admiralty after the British plan to attempt a naval capture of the Turkish-controlled Dardanelle Straits met with resounding failure in mid-to-late 1915. Reduced to a minor ministerial position, Churchill resigned from the government in November 1915 and rejoined the army, heading  to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.

to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.