philippines

War heroes come in many forms, and Colonel Ruby Bradley was one of the great ones. Born on December 19, 1907 in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia the daughter of Fred O Bradley and Bertha Welch. Bradley was the fifth of six children, and she was raised on a farm in Roane County, West Virginia. From a young age, she was taught to work hard on her parents farm. Farm kids are not strangers to hard work. The farm animals and the crops require that every member of the family had to do their part, meaning men, women, and children to assume many roles such as manual labor. From an early age, Ruby understood the worth of manual labor and hard work. She was a hard worker and she was not a quitter.

War heroes come in many forms, and Colonel Ruby Bradley was one of the great ones. Born on December 19, 1907 in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia the daughter of Fred O Bradley and Bertha Welch. Bradley was the fifth of six children, and she was raised on a farm in Roane County, West Virginia. From a young age, she was taught to work hard on her parents farm. Farm kids are not strangers to hard work. The farm animals and the crops require that every member of the family had to do their part, meaning men, women, and children to assume many roles such as manual labor. From an early age, Ruby understood the worth of manual labor and hard work. She was a hard worker and she was not a quitter.

Bradley’s life took a drastic turn during World War II. Prior to World War II, as a career Army nurse, Colonel Ruby Bradley served as the hospital administrator in Luzon in the Philippines. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, three weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she and a doctor and fellow nurse hid in the hills. Unfortunately, they were turned in by locals and taken to the base, which had been turned into a prison camp. In 1943, Bradley was moved to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila. It was there that she and several other imprisoned nurses earned the title “Angels in Fatigues” from fellow captives. For the next several months, she provided medical help to the prisoners and sought to feed starving children by shoving food into her pockets whenever she could, often going hungry herself. As she lost weight, she used the room in her uniform for smuggling surgical equipment into the prisoner-of-war camp. At the camp she assisted in 230 operations and helped to deliver 13 children. Bradley and her staff spent three years treating fellow POWs, delivering babies, and performing surgery. They also smuggled supplies to keep the POWs healthy, although Bradley herself weighed a mere 84 pounds when the Americans liberated the camp in 1945.

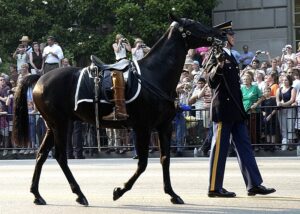

After the war, Bradley served in the Korean War as the 8th Army’s chief nurse on the front lines in 1950. During a heavy fire attack, Bradley managed to evacuate all of the wounded soldiers in her care, doing so without regard for her own safety. She was the last to jump aboard the evacuation plane just as her ambulance was shelled. After her actions during that attack, she was promoted to Colonel. She retired from the Army in 1963, but worked as a supervising nurse in West Virginia for 17 years. Ruby Bradley is known as the most decorated woman in US history, having received 34 medals and citations, including Legion of Merit with oak leaf cluster, Bronze Star Medal with oak leaf cluster, Army Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster, Prisoner of War Medal, Presidential Unit Citation with oak leaf cluster, Meritorious Unit Commendation, American Defense Service Medal with “Foreign Service” clasp, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two campaign stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with “Japan” clasp, National Defense Service Medal with star, Korean Service Medal with three campaign stars, Philippine Defense Medal (Republic of Philippines) with star, Philippine Liberation Medal (Republic of Philippines) with star, Philippine Independence Medal (Republic of Philippines), United Nations Service Medal, Korean War Service Medal (Republic of Korea), and Florence Nightingale Medal (International Red Cross). Colonel Ruby Bradley died of a heart attack on May 28, 2002. She received a hero’s  funeral with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. “Her coffin was escorted to the grave site by six white horses, and the symbolic riderless horse followed, while the Army Band played traditional hymns. “A riderless horse (which may be caparisoned in ornamental and protective coverings, having a detailed protocol of their own) is a single horse, without a rider, and with boots reversed in the stirrups, which sometimes accompanies a funeral procession. The horse follows the caisson carrying the casket.” A firing party of seven sounded three volleys in her honor, and the flag covering her coffin was presented to a relative.” Many family members and Army soldiers paid their respects by placing roses on top of the coffin and also saluting her resting place as they left. She was 94.

funeral with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. “Her coffin was escorted to the grave site by six white horses, and the symbolic riderless horse followed, while the Army Band played traditional hymns. “A riderless horse (which may be caparisoned in ornamental and protective coverings, having a detailed protocol of their own) is a single horse, without a rider, and with boots reversed in the stirrups, which sometimes accompanies a funeral procession. The horse follows the caisson carrying the casket.” A firing party of seven sounded three volleys in her honor, and the flag covering her coffin was presented to a relative.” Many family members and Army soldiers paid their respects by placing roses on top of the coffin and also saluting her resting place as they left. She was 94.

When we think of Prisoners of War during the world wars, we usually think of the prisoners as being men, but there were women too…nurses. At that time, women couldn’t be in combat positions, and if they wanted to serve their country, it had to be as nurses or medics. One group of United States Army Nurse Corps and United States Navy Nurse Corps nurses, were stationed in the Philippines at the outset of the Pacific War, were later dubbed the Angels of Bataan (also including the the nurses of the island of Corregidor), were also called the Angels of Bataan and Corregidor and the Battling Belles of Bataan. The 78 nurses served during the Battle of the Philippines (1941–42). When Bataan and Corregidor fell, 11 Navy nurses, 66 army nurses, and 1 nurse-anesthetist were captured and imprisoned in and around Manila. These loyal, patriotic women continued to serve as a nursing unit while prisoners of war, taking care of their fellow prisoners, even if it meant punishment for their actions.

When we think of Prisoners of War during the world wars, we usually think of the prisoners as being men, but there were women too…nurses. At that time, women couldn’t be in combat positions, and if they wanted to serve their country, it had to be as nurses or medics. One group of United States Army Nurse Corps and United States Navy Nurse Corps nurses, were stationed in the Philippines at the outset of the Pacific War, were later dubbed the Angels of Bataan (also including the the nurses of the island of Corregidor), were also called the Angels of Bataan and Corregidor and the Battling Belles of Bataan. The 78 nurses served during the Battle of the Philippines (1941–42). When Bataan and Corregidor fell, 11 Navy nurses, 66 army nurses, and 1 nurse-anesthetist were captured and imprisoned in and around Manila. These loyal, patriotic women continued to serve as a nursing unit while prisoners of war, taking care of their fellow prisoners, even if it meant punishment for their actions.

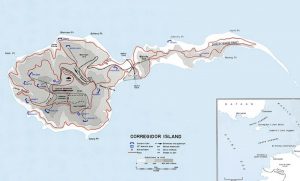

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese immediately went after the Philippines and the military personnel based there, including the nurses. In late December 1941, many of the nurses were assigned to a pair of battlefield hospitals on Bataan named Hospital #1 and Hospital #2. These hospitals included the first open-air wards since the Civil War. Tropical diseases, including malaria and dysentery, were widespread among both hospital patient and staff. Just prior to the fall of Bataan on April 9, 1942, the nurses serving there were ordered to the island fortress of Corregidor by General Wainwright (commander of the forces in the Philippines after MacArthur was ordered to Australia). Wainwright tried to save as many people as he could by moving them to the safer island of Corregidor. In the end it made no difference, because Corregidor was captured too.

During their occupation of the Philippines, the Japanese commandeered the campus of the University of Santo Tomas and converted it to be the Santo Tomas Internment Camp. In addition to its civilian population, Santo Tomas became the initial internment camp for both the army and navy nurses, with the army nurses remaining there until their liberation, while the soldiers were taken on the Bataan Death March. While there, the nurses continued to take care of anyone they were allowed to. Under the supervision of Captain Maude C Davison, a 57 year old nurse, with 20 years of service experience, the nurses continued to do their jobs. Davison took command of the nurses, maintained a regular schedule of nursing duty, and insisted that all nurses wear their khaki blouses and skirts while on duty.

The number of internees at Santo Tomas Internment Center in February 1942 amounted to approximately 4,670 people, of whom 3,200 Americans. Of those 3,200 Americans, 78 were nurses. The Americans, anticipating the war, had sent many wives and children of American men employed in the Philippines to the states before December 8, 1941. A few people had been sent to the Philippines from China to escape the war in that country. Some had arrived only days before the Japanese attack. The prisoners were crowded 30 to 50 people per small classrooms in university buildings. The allotment of space for each individual was 16 to 22 square feet. Bathrooms were scarce. Twelve hundred men living in the main building had 13 toilets and 12 showers. Lines were normal for toilets and meals. Internees with money were able to buy food and built huts, “shanties,” of bamboo and palm fronds in open ground where they could take refuge during the day, although the Japanese insisted that all internees sleep in their assigned rooms at night. Soon there were several hundred shanties and their owners constituted a “camp aristocracy.” The Japanese attempted to enforce a ban on sex, marriage, and displays of affection among the internees. They often complained to the Executive Committee about “inappropriate” relations between men and women in the shanties.

The conditions at Santo Tomas were horrific. The biggest problem for the internees was sanitation, followed closely by starvation. The Sanitation and Health Committee had more than 600 internee men working for it. Their tasks included building more toilets and showers, laundry, dishwashing, and cooking facilities, disposal of garbage, and controlling the flies, mosquitoes, and rats that infested the compound. Then, in January 1944, control of the Santo Tomas Internment Camp changed from Japanese civil authorities to the Imperial Japanese Army, with whom it remained until the camp was liberated. Food, which had been scarce before, was reduced to only 960 calories per person per day by November 1944, and then to 700 calories per person per day by  January 1945. At the time the nurses were finally released, it was found that they had lost, on average, 30% of their body weight during internment, and subsequently experienced a degree of service-connected disability “virtually the same as the male ex-POW’s of the Pacific Theater.” Davison’s body weight dropped from 156 pounds to 80 pounds.

January 1945. At the time the nurses were finally released, it was found that they had lost, on average, 30% of their body weight during internment, and subsequently experienced a degree of service-connected disability “virtually the same as the male ex-POW’s of the Pacific Theater.” Davison’s body weight dropped from 156 pounds to 80 pounds.

Finally, General Douglas MacArthur, emboldened by the success of the Raid at Cabanatuan, ordered Major General Vernon D Mudge to make an aggressive raid on Santo Tomas in the Battle of Manila in 1945. The internees at Santo Tomas, including the nurses, were liberated on February 3, 1945, by a “flying column” of the 1st Cavalry.

Shortly after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they were bent on making the most of the advantage they had, or perceived to have had. As we know the advantage was much less than they thought it was, but the United States did need a little bit of time to regroup and prepare for their entrance into World War II. The invasion of the Philippines started on December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The US military had just lost ships and personnel, and understandably, the Japanese saw the opportunity to take advantage of the chaos. As at Pearl Harbor, American aircraft were severely damaged in the initial Japanese attack on the Philippines. A lack of air cover, forced the American Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines withdrew to Java on December 12, 1941. General Douglas MacArthur was ordered out of harms way. He was sent to Australia, 2485 miles away, unfortunately leaving his men at Corregidor on the night of March 11, 1942. Cutting off supplies, the Japanese finally forced 76,000 starving and sick American and Filipino defenders in Bataan to surrender on April 9, 1942. They were then forced to endure the infamous Bataan Death March on which 7,000 to 10,000 people died or were murdered.

Shortly after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they were bent on making the most of the advantage they had, or perceived to have had. As we know the advantage was much less than they thought it was, but the United States did need a little bit of time to regroup and prepare for their entrance into World War II. The invasion of the Philippines started on December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The US military had just lost ships and personnel, and understandably, the Japanese saw the opportunity to take advantage of the chaos. As at Pearl Harbor, American aircraft were severely damaged in the initial Japanese attack on the Philippines. A lack of air cover, forced the American Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines withdrew to Java on December 12, 1941. General Douglas MacArthur was ordered out of harms way. He was sent to Australia, 2485 miles away, unfortunately leaving his men at Corregidor on the night of March 11, 1942. Cutting off supplies, the Japanese finally forced 76,000 starving and sick American and Filipino defenders in Bataan to surrender on April 9, 1942. They were then forced to endure the infamous Bataan Death March on which 7,000 to 10,000 people died or were murdered.

The 13,000 survivors on the island of Corregidor surrendered on May 6, 1942. It was the last holdout against the Japanese in the Philippines. The surrender of the Philippines and Corregidor was not only a sad thing…it was a death sentence for many. The island of Corregidor under the command of General Jonathan Wainwright, was hit by constant artillery shelling and aerial bombardment attacks, which ate away at the American and Filipino defenders. The troops at Corregidor managed to sink many Japanese barges as they approached the northern shores of the island with necessary supplies, but finally, cut off from supplies, the Allied troops couldn’t hold the invader off any longer. General Wainwright, who had only recently been promoted to the rank of lieutenant general and commander of the US armed forces in the Philippines, offered to surrender Corregidor to Japanese General Homma, but Homma wanted the complete, unconditional surrender of all American forces throughout the Philippines. Wainwright had little choice given the odds against him and the poor physical condition of his troops. He had already lost 800 men. He surrendered at midnight. All 11,500 surviving Allied troops were evacuated to a prison stockade in Manila.

The Japanese did not care about any kind of proper treatment of the prisoners of war. Men were beaten,  starved, and worked to death. Many of the men who surrendered at Corregidor were sent to Japan to work there. No one knew where they were, or even if they were still alive. At first, it was thought that they were in the prison camps, but people only later heard that their loved one was…who knew where. General Wainwright remained a POW until 1945. I’m sure the US government felt bad that they couldn’t help him, and so he was invited to the USS Missouri for the formal Japanese surrender ceremony on September 2, 1945. He was also be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Harry S Truman. Wainwright died in 1953…eight years to the day of the Japanese surrender ceremony.

starved, and worked to death. Many of the men who surrendered at Corregidor were sent to Japan to work there. No one knew where they were, or even if they were still alive. At first, it was thought that they were in the prison camps, but people only later heard that their loved one was…who knew where. General Wainwright remained a POW until 1945. I’m sure the US government felt bad that they couldn’t help him, and so he was invited to the USS Missouri for the formal Japanese surrender ceremony on September 2, 1945. He was also be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Harry S Truman. Wainwright died in 1953…eight years to the day of the Japanese surrender ceremony.