pearl harbor

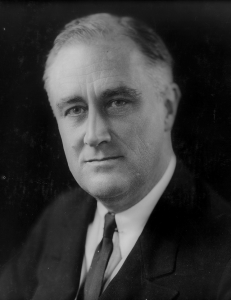

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

The attack on Pearl Harbor took so many people by surprise. It was a Sunday morning, and many of the military personnel were off base attending church services. The Japanese knew that the ships, planes, and the base in general would be seriously understaffed at the time of the attack. Of course, on the flip side, the fact that so many of the military personnel were away from the base at the time of the attack, meant that the base was able to get back up and running quickly and when we did enter the war, the Japanese were surprised about the attacks coming back at them. Of course, as we all know, the Allies went on to win the war against the Axis nation, including Germany and Japan. It’s been said that people shouldn’t wake the sleeping giant, and that is a wise statement. The Japanese awakened the United States to the fact that appeasing your enemies will not prevent an attack. It takes a show of military might to inform our enemies that it is wise to back away and let the sleeping giants lie.

Of course, the victory that was won following the attack of Pearl Harbor and the US entrance into World War II, came at a high price. A total of 2,403 people (both civilians and soldiers), not to mention ships, airplanes, and

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

To call the Pearl Harbor attack, a “mistake on the part of the Japanese,” seems like a case of serious misinformation, on the part of the one who made such a comment, Admiral Chester A Nimitz. Nevertheless, that is what he said on Christmas Day, 1941, after he toured the destruction of his new duty station shortly after his Christmas Eve arrival. Anyone who would have heard Nemitz comments probably thought the new Commander of the Pacific Fleet might be just a little bit “off his rocker!!” Where everyone else saw all the ships sunken and knew of the 3,800 men who lost their lives that day, and in their minds, there was nothing good about all this, so what was the admiral thinking.

To call the Pearl Harbor attack, a “mistake on the part of the Japanese,” seems like a case of serious misinformation, on the part of the one who made such a comment, Admiral Chester A Nimitz. Nevertheless, that is what he said on Christmas Day, 1941, after he toured the destruction of his new duty station shortly after his Christmas Eve arrival. Anyone who would have heard Nemitz comments probably thought the new Commander of the Pacific Fleet might be just a little bit “off his rocker!!” Where everyone else saw all the ships sunken and knew of the 3,800 men who lost their lives that day, and in their minds, there was nothing good about all this, so what was the admiral thinking.

Sunday, December 7th, 1941, found Admiral Chester Nimitz attending a concert in Washington, DC. He received a page and was told that he had a phone call. On the other end was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who told Admiral Nimitz that his new assignment was to be the Commander of the Pacific Fleet. Admiral Nimitz flew to Hawaii to assume command of the Pacific Fleet, arriving to see such a spirit of despair, dejection, and defeat. It seemed that everyone thought the Japanese had already won the war. As the tour boat returned to dock, the young helmsman of the boat asked, “Well Admiral, what do you think after seeing all this destruction?” The admiral’s reply shocked everyone within the sound of his voice. Admiral Nimitz said, “The Japanese made three of the biggest mistakes an attack force could ever make, or God was taking care of America. Which do you think it was?” Shocked and surprised, the young helmsman asked, “What do mean by saying the Japanese made the three biggest mistakes an attack force ever made?”

What was meant, is really the difference between the thinking of an enlisted man, and the thinking of a great strategist, such as Admiral Nemitz was. I’m actually quite sure most of us would have fallen more in line with

the enlisted helmsman…basically seeing the trees and missing the forest. So, Admiral Nemitz had to enlighten those around him. The first mistake made by the Japanese, is actually one I had heard before, and likely the “best” mistake for the people concerned. The attack on Pearl Harbor took place on a Sunday morning…when many of the men who might have been on the ships, were on leave. In fact, nine out of ten of the men stationed on the ships were on leave. That cut the loss of life down by 90%. As Admiral Nemitz told the people, “If those same ships had been lured to sea and been sunk–we would have lost 38,000 men instead of 3,800.” Now the Japanese had angered the “Sleeping Giant” that was the United States and left the majority of the fighting force to exact their revenge.

the enlisted helmsman…basically seeing the trees and missing the forest. So, Admiral Nemitz had to enlighten those around him. The first mistake made by the Japanese, is actually one I had heard before, and likely the “best” mistake for the people concerned. The attack on Pearl Harbor took place on a Sunday morning…when many of the men who might have been on the ships, were on leave. In fact, nine out of ten of the men stationed on the ships were on leave. That cut the loss of life down by 90%. As Admiral Nemitz told the people, “If those same ships had been lured to sea and been sunk–we would have lost 38,000 men instead of 3,800.” Now the Japanese had angered the “Sleeping Giant” that was the United States and left the majority of the fighting force to exact their revenge.

Of course, that was only their first mistake. Their second mistake was that when the Japanese saw all those battleships lined up in a row, they got so carried away sinking the battleships, they either didn’t notice, or forgot about the dry docks opposite those ships. Leaving the dry docks, meant that instead of towing every one of those ships to the America to be repaired, they could simply be raised from the shallow water they were in, and one tug could pull them over to the dry docks. Any salvageable ships could be repaired and back out at sea by the time they could have towed them to the America. Add that fact to the already established fact that Admiral Nemitz already had crews ashore anxious to man those ships. They were ready to fight.

The final mistake made by the Japanese was that they were either unaware of or forgot about the above-ground fuel storage tanks located just five miles away over the next hill. In fact, every drop of fuel in the Pacific theater of war was sitting out there in those tanks, and even if the ships were ready to go and fully manned, the lack of fuel would have prevented an attack on the Japanese fleet.

While everyone around him was thinking of the devastation and the defeat of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nemitz saw the three biggest mistakes of the Japanese government, or as he preferred to call it, that

“God was taking care of America.” I tend to agree with Admiral Nemitz in that I, too, think it was God taking care of us. My thought is that the Japanese knew about the dry docks and the fuel storage, but in their “excitement” at pulling off the surprise attack, they forgot all about them. Of course, there is that first mistake of planning an attack of God’s Day. Seriously, they chose to take on the whole Pacific Fleet…and God too!! Wow!! It’s hard to be more “stupid” than that.

“God was taking care of America.” I tend to agree with Admiral Nemitz in that I, too, think it was God taking care of us. My thought is that the Japanese knew about the dry docks and the fuel storage, but in their “excitement” at pulling off the surprise attack, they forgot all about them. Of course, there is that first mistake of planning an attack of God’s Day. Seriously, they chose to take on the whole Pacific Fleet…and God too!! Wow!! It’s hard to be more “stupid” than that.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, rocked the United States. It was so unexpected, but while it brought so much destruction, it also brought out so many heroes too. Orders did not need to be given, everyone simply jumped into action, without being told. Still, the destruction was so overwhelming, and the attack just kept coming. People were dodging bullets and bombs, as well as flying debris and suicide bombers. A heavy, choking, acrid smoke filled the air, making it very hard to breathe. There would be making deaths that day, but there would also be heroes.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, rocked the United States. It was so unexpected, but while it brought so much destruction, it also brought out so many heroes too. Orders did not need to be given, everyone simply jumped into action, without being told. Still, the destruction was so overwhelming, and the attack just kept coming. People were dodging bullets and bombs, as well as flying debris and suicide bombers. A heavy, choking, acrid smoke filled the air, making it very hard to breathe. There would be making deaths that day, but there would also be heroes.

Lieutenant Annie G Fox was stationed at Hickam Airfield in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, and she was the chief nurse on duty that morning. When the attack began, she sprang into action to tend to the injured and dying service personnel on the base. For her outstanding performance, Fox was recommended for and awarded the Purple Heart, but she was not injured during the attack. Fox was presented the Purple Heart on October 26, 1942, at Hickam Field. Colonel William Boyd, Post Commander read the  citation which was commanded by Brigadier General W E Farthing and signed by Colonel L P Turner, Air Corps Executive Officer.

citation which was commanded by Brigadier General W E Farthing and signed by Colonel L P Turner, Air Corps Executive Officer.

Then, in 1944 in a horrible twist of fate, the rules for receiving the Purple Heart changed, and Fox no longer qualified. The recipient needed to have sustained battle wounds. Fox’s medal was rescinded. She received the Bronze Star instead. I can understand the reasons behind the change, but it seems wrong that her medal that was legitimately earned in 1941, could be taken back in 1944. It should have been grandfathered or something. Nevertheless, the Purple Heart was not returned.

Purple Heart or Bronze Star aside, Lieutenant Annie Fox showed great spirit that day. In the face of great  personal danger, she dodged the hail of bullets to reach many wounded people and she saved many lives. She could have been shot, bombed, breathed in poisonous gasses, or been hit by debris. It didn’t stop her. She saw the wounded, and she ran headlong into the danger, thereby saving her fellow man. Whether she was properly awarded the Purple Heart or not, she was definitely a hero.

personal danger, she dodged the hail of bullets to reach many wounded people and she saved many lives. She could have been shot, bombed, breathed in poisonous gasses, or been hit by debris. It didn’t stop her. She saw the wounded, and she ran headlong into the danger, thereby saving her fellow man. Whether she was properly awarded the Purple Heart or not, she was definitely a hero.

Annie Gayton Fox was born to Charles Fox and Deidamia (Gayton) Fox in East Pubnico, Nova Scotia, Canada, on August 4, 1893. She died at age 93 on January 20, 1987, in San Mateo County, California. Her years of service ran from July 3, 1918 through December 31, 1945. She retired as a Major in the US Army.

War heroes come in many forms, and Colonel Ruby Bradley was one of the great ones. Born on December 19, 1907 in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia the daughter of Fred O Bradley and Bertha Welch. Bradley was the fifth of six children, and she was raised on a farm in Roane County, West Virginia. From a young age, she was taught to work hard on her parents farm. Farm kids are not strangers to hard work. The farm animals and the crops require that every member of the family had to do their part, meaning men, women, and children to assume many roles such as manual labor. From an early age, Ruby understood the worth of manual labor and hard work. She was a hard worker and she was not a quitter.

War heroes come in many forms, and Colonel Ruby Bradley was one of the great ones. Born on December 19, 1907 in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia the daughter of Fred O Bradley and Bertha Welch. Bradley was the fifth of six children, and she was raised on a farm in Roane County, West Virginia. From a young age, she was taught to work hard on her parents farm. Farm kids are not strangers to hard work. The farm animals and the crops require that every member of the family had to do their part, meaning men, women, and children to assume many roles such as manual labor. From an early age, Ruby understood the worth of manual labor and hard work. She was a hard worker and she was not a quitter.

Bradley’s life took a drastic turn during World War II. Prior to World War II, as a career Army nurse, Colonel Ruby Bradley served as the hospital administrator in Luzon in the Philippines. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, three weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she and a doctor and fellow nurse hid in the hills. Unfortunately, they were turned in by locals and taken to the base, which had been turned into a prison camp. In 1943, Bradley was moved to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila. It was there that she and several other imprisoned nurses earned the title “Angels in Fatigues” from fellow captives. For the next several months, she provided medical help to the prisoners and sought to feed starving children by shoving food into her pockets whenever she could, often going hungry herself. As she lost weight, she used the room in her uniform for smuggling surgical equipment into the prisoner-of-war camp. At the camp she assisted in 230 operations and helped to deliver 13 children. Bradley and her staff spent three years treating fellow POWs, delivering babies, and performing surgery. They also smuggled supplies to keep the POWs healthy, although Bradley herself weighed a mere 84 pounds when the Americans liberated the camp in 1945.

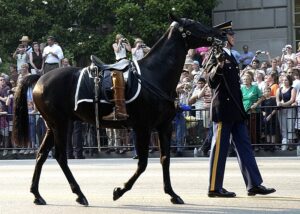

After the war, Bradley served in the Korean War as the 8th Army’s chief nurse on the front lines in 1950. During a heavy fire attack, Bradley managed to evacuate all of the wounded soldiers in her care, doing so without regard for her own safety. She was the last to jump aboard the evacuation plane just as her ambulance was shelled. After her actions during that attack, she was promoted to Colonel. She retired from the Army in 1963, but worked as a supervising nurse in West Virginia for 17 years. Ruby Bradley is known as the most decorated woman in US history, having received 34 medals and citations, including Legion of Merit with oak leaf cluster, Bronze Star Medal with oak leaf cluster, Army Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster, Prisoner of War Medal, Presidential Unit Citation with oak leaf cluster, Meritorious Unit Commendation, American Defense Service Medal with “Foreign Service” clasp, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two campaign stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with “Japan” clasp, National Defense Service Medal with star, Korean Service Medal with three campaign stars, Philippine Defense Medal (Republic of Philippines) with star, Philippine Liberation Medal (Republic of Philippines) with star, Philippine Independence Medal (Republic of Philippines), United Nations Service Medal, Korean War Service Medal (Republic of Korea), and Florence Nightingale Medal (International Red Cross). Colonel Ruby Bradley died of a heart attack on May 28, 2002. She received a hero’s  funeral with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. “Her coffin was escorted to the grave site by six white horses, and the symbolic riderless horse followed, while the Army Band played traditional hymns. “A riderless horse (which may be caparisoned in ornamental and protective coverings, having a detailed protocol of their own) is a single horse, without a rider, and with boots reversed in the stirrups, which sometimes accompanies a funeral procession. The horse follows the caisson carrying the casket.” A firing party of seven sounded three volleys in her honor, and the flag covering her coffin was presented to a relative.” Many family members and Army soldiers paid their respects by placing roses on top of the coffin and also saluting her resting place as they left. She was 94.

funeral with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. “Her coffin was escorted to the grave site by six white horses, and the symbolic riderless horse followed, while the Army Band played traditional hymns. “A riderless horse (which may be caparisoned in ornamental and protective coverings, having a detailed protocol of their own) is a single horse, without a rider, and with boots reversed in the stirrups, which sometimes accompanies a funeral procession. The horse follows the caisson carrying the casket.” A firing party of seven sounded three volleys in her honor, and the flag covering her coffin was presented to a relative.” Many family members and Army soldiers paid their respects by placing roses on top of the coffin and also saluting her resting place as they left. She was 94.

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

When a war begins, I doubt if anyone is thinking about the medals or the honors they might receive, because what they really want is for the war to be over already. Nobody enjoys going to war…not even the one who starts the war. There are never any guarantees that you will come out of a war alive, so most people would rather not go at all. Nevertheless, when a soldier goes into war, he or she has taken a vow to do their very best, and to fight to the death, if necessary. When World War II got started, the United States really intended to stay out of it. They vowed to stay neutral…until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Once the United States entered World War II, however, we were in it to win it.

Lieutenant Edward O’Hare, an American naval aviator of the United States Navy, was born on March 13, 1914 in Saint Louis, Missouri, to Selma Anna (Lauth) and Edward Joseph O’Hare. He was of Irish and German descent. Edward, who was nicknamed “Butch,” had two sisters, Patricia and Marilyn. Their parents divorced in 1927. Butch and his sisters stayed with their mother in Saint Louis, and their father moved to Chicago. O’Hare joined the Navy, and from there, life moved pretty fast. On July 21, 1941, O’Hare met his future wife, Rita and asked her to marry him that night. He knew immediately that she was the one. They got married on September 6, 1941 and their daughter, Kathleen was born in January or February of 1943. O’Hare first met her when she was a month old, because of missions he was on.

In the Navy, O’Hare was stationed first on the USS Saratoga, then on the USS Enterprise, and then on the USS Lexington, flying a Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat. In mid-February 1942, the Lexington sailed into the Coral Sea. A town named Rabaul, at the very tip of New Britain, one of the islands that comprised the Bismarck Archipelago, had been invaded in January by the Japanese and transformed into a stronghold. In fact, it had been turned into one huge airbase. The occupation of Rabaul put the Japanese in prime striking position for the Solomon Islands, which would have been put them in a perfect position for expanding their ever-growing Pacific empire. Given the mission of destabilizing the Japanese position on Rabaul with a bombing raid, the fighters on the Lexington took off from the aircraft carrier’s deck in a raid against the Japanese position at Rabaul. Just moments later, Lieutenant O’Hare became America’s first World War II flying ace. In the battle that took place on February 20, 1942, O’Hare believed he had shot down six bombers and damaged a seventh. Captain Frederick C Sherman later reduced that number to five, as four of the reported nine bombers were still overhead when he pulled off. Nevertheless, in the opinion of Admiral Brown and of Captain Sherman, commanding the Lexington, Lieutenant O’Hare’s actions may have saved the carrier from serious damage or even loss. In a mere four minutes, O’Hare shot down five Japanese G4M1 Betty bombers, bringing a swift end to the Japanese attack and earning O’Hare the designation “Ace,” which was given to any pilot who had five or more downed enemy planes to his credit. The attack on the bombers was great, but it ruined the element of surprise, so the mission was called off.

On the night of November 26, 1943, the USS Enterprise introduced the experiment in the co-operative control of Avengers and Hellcats for night fighting. The team consisted of three planes, breaking up a large group of land-based bombers. O’Hare volunteered to lead this mission to conduct the first-ever Navy nighttime fighter

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.

attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O’Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. It was to be his final mission. When it was over, O’Hare was missing in action. He was declared dead a year later. The airport in Chicago and a destroyer would later be named in his honor. He lived life fast and died young, but he was always in it to win it.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

There were heroes on that day, however. The people who worked to save what lives they could, and put out the fires caused by the attack. And there were two heroes I had never heard about. I’m not sure why I hadn’t, but the fact remains that I hadn’t. Kenneth Taylor and George Welch were pilots stationed at Pearl Harbor on that fateful day. Taylor was a second lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps’ 47th Pursuit Squadron. He received his first posting to Wheeler Army Airfield in Honolulu, Hawaii in April 1941. His commanding officer, General Gordon Austin, chose Taylor and another pilot, George Welch, as his flight commanders shortly after they arrived in Hawaii. A week before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 47th Pursuit Squadron was temporarily moved to the auxiliary airstrip at Haleiwa Field, located some 11 miles from Wheeler, for gunnery practice…a move that made their response to the attack possible.

Saturday, December 6, 1941, found Taylor and Welch spending the evening at a dance held at the officers’ club at Wheeler Field. After the dance, the two pilots joined an all-night poker game. After that, the account of the story gets a little fuzzy. Some said that the two pilots had finally gone to sleep, and were awoken only around 7:51am, when Japanese fighter planes and dive bombers attacked Wheeler, but others said that the poker game was just wrapping up, and they were contemplating a morning swim when the attack began. Whatever the case may be, Taylor and Welch were stunned to hear low-flying planes, explosions, and machine-gun fire above them. Information was scarce in all the chaos, but they learned that two-thirds of the planes at the main bases of Hickham and Wheeler Fields had been destroyed or damaged so badly that they were unable to fly. The two men rush to Haleiwa Field to get their planes. They had no orders, but Taylor called Haleiwa and  commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

When they reached the field, Welch and Taylor jumped into their P-40s, which by that time had been fueled but not fully armed. That didn’t stop them. They took off and immediately attracted Japanese fire. Welch and Taylor were facing off virtually alone against some 200 to 300 enemy aircraft. When they ran out of ammunition, they returned to Wheeler to reload. The senior officers ordered the pilots to stay on the ground, but then

the second wave of Japanese raiders flew in, scattering the crowd. Taylor and Welch took off again, in the midst of a swarm of enemy planes. Though Welch’s machine guns were disconnected, he fired his .30-caliber guns, destroying two Japanese planes on the first attack run. On the second, with his plane heavily damaged by gunfire, he shot down two more enemy aircraft. A bullet pierced the canopy of Taylor’s plane, hitting his arm and sending shrapnel into his leg, but he managed to shoot down at least two Japanese planes, and perhaps more. In the end, Taylor was officially credited with two kills, and Welch with four.

Welch and Taylor were among only five Air Force pilots who managed to get their planes off the ground and engage the Japanese that morning. The total loss in aircraft at Pearl Harbor were estimated at 188 planes destroyed and 159 damaged. The Japanese lost just 29 planes. Both men were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross medals, becoming the first to be awarded that distinction in World War II. Welch was nominated for the Medal of Honor, the military’s highest award, but was reportedly denied because his superiors maintained he had taken off without proper authorization. For his injuries, Taylor received the Purple Heart.

After Pearl Harbor, George Welch flew nearly 350 missions in the Pacific Theater during World War II, shooting down 12 more planes and winning many other decorations. After he contracted malaria in 1943, his wartime career came to an end. While in the hospital in Sydney, Australia, he met his wife. After the war, Welch became a test pilot for North American Aviation. There are some claims that he became the first pilot to break the Mach-1 barrier with an unauthorized flight over the California desert in 1947, several weeks before Chuck Yeager’s famous flight. Unfortunately, Welch was killed in 1954 while ejecting from his disintegrating F-100 Super Sabre fighter jet during a test flight.

After Pearl Harbor, Ken Taylor was transferred to the South Pacific, where he flew out of Guadalcanal and was credited with downing another Japanese aircraft. Unfortunately, his combat career was cut short after someone fell on top of him in a trench during an air raid on the base, breaking his leg. He became a commander in the Alaska Air National Guard and retired as a brigadier general after 27 years of active duty. Taylor was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion of Merit, the Air Medal, and a number of other decorations. In his post military career, he worked as an insurance underwriter. Taylor died in Tucson, Arizona in 2006, at the age of 86.

A sneak attack…not something that happens overnight. That kind of attack takes planning. Relations between the United States and Japan had not been good, but now with Japan’s occupation of Indo-China and the implicit menacing of the Philippines, an American protectorate, they were deteriorating rapidly. The Americans had retaliated by seizing of all Japanese assets in the United States. That action was followed by the closing of the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt issued a statement, drafted by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, that threatened war between the United States and Japan should the Japanese encroach any farther on territory in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific.

A sneak attack…not something that happens overnight. That kind of attack takes planning. Relations between the United States and Japan had not been good, but now with Japan’s occupation of Indo-China and the implicit menacing of the Philippines, an American protectorate, they were deteriorating rapidly. The Americans had retaliated by seizing of all Japanese assets in the United States. That action was followed by the closing of the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt issued a statement, drafted by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, that threatened war between the United States and Japan should the Japanese encroach any farther on territory in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific.

The Japanese were keen to wield more power on the people of the earth. To do that, they had to take down the biggest super power, the United States of America. And to protect themselves, they needed to take Hawaii out of the hands of the United States, because it was a gateway in the Pacific that they couldn’t afford to have in the hands of the Allies. On September 24, 1941, the Japanese consul in Hawaii was instructed to divide Pearl Harbor into five zones, calculate the number of battleships in each zone, and report the findings back to Japan. They were preparing for the attack they had planned for December.

The Japanese military had long dominated Japanese foreign affairs. The official negotiations between the United States secretary of state and his Japanese counterpart to ease tensions were still ongoing, but Hideki Tojo, the minister of war who would soon be prime minister, had no intention of withdrawing from captured territories…even if the negotiations required it. He also decided that the American “threat” of war as an ultimatum, and he made plans to attack first in a Japanese-American confrontation: the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

As the plans began to gear up, Japan didn’t know that the United States had intercepted the message. Most unfortunate, was the fact that the message was sent back to Washington for decrypting. There were not a lot of

flights east, so the message was sent via sea. That process took more time. When it finally arrived at the capital, staff shortages and other priorities further delayed the decryption. When the message was finally unscrambled in mid-October, it was dismissed as being of no great consequence. It was a huge error on the part of the American intelligence community, and on December 7th, everyone would know that.

flights east, so the message was sent via sea. That process took more time. When it finally arrived at the capital, staff shortages and other priorities further delayed the decryption. When the message was finally unscrambled in mid-October, it was dismissed as being of no great consequence. It was a huge error on the part of the American intelligence community, and on December 7th, everyone would know that.

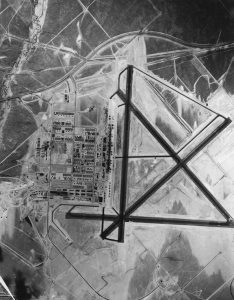

Prior to December 7, 1941, the United States had signed a Proclamation of Neutrality. They did not want to get pulled into World War II, any more than they had World War I and any of the other wars they were involved in. Still, I think everyone knew that it was inevitable…even before the Japanese attack. Early on the Sunday morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and almost simultaneously at other locations in the Pacific, would end any continued semblance of neutrality, and the United States prepared for war. The response to the attack was quick and decisive. The US Army Air Force (USAAF), under the command of Major General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold was authorized to equip, man, and train itself into the world’s most powerful air force, and to do so quickly. The first order of business was to establish air force bases. By early 1942, the USAAF had committed to building scores of air bases across the United States. Everyone wanted to help, so a Chamber of Commerce delegation from Casper, Wyoming, traveled to Washington DC, to lobby for one of the proposed air bases. According to Joye Kading, longtime secretary at the Casper Army Air Base, they marketed the “zephyr wind” that whips around the western end of Casper Mountain as part of what made it a perfect location. The USAAF agreed.

Prior to December 7, 1941, the United States had signed a Proclamation of Neutrality. They did not want to get pulled into World War II, any more than they had World War I and any of the other wars they were involved in. Still, I think everyone knew that it was inevitable…even before the Japanese attack. Early on the Sunday morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and almost simultaneously at other locations in the Pacific, would end any continued semblance of neutrality, and the United States prepared for war. The response to the attack was quick and decisive. The US Army Air Force (USAAF), under the command of Major General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold was authorized to equip, man, and train itself into the world’s most powerful air force, and to do so quickly. The first order of business was to establish air force bases. By early 1942, the USAAF had committed to building scores of air bases across the United States. Everyone wanted to help, so a Chamber of Commerce delegation from Casper, Wyoming, traveled to Washington DC, to lobby for one of the proposed air bases. According to Joye Kading, longtime secretary at the Casper Army Air Base, they marketed the “zephyr wind” that whips around the western end of Casper Mountain as part of what made it a perfect location. The USAAF agreed.

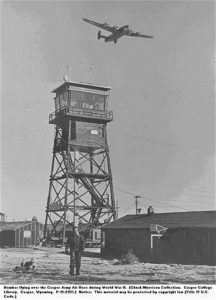

In March 1942, the US Army Corps of Engineers leased the old Casper City Hall at Center and Eighth streets in downtown Casper, in preparation for the construction of the new Army Air Base at Casper. The site they selected was a high, flat, sagebrush-covered terrace located nine miles west of town on US Highway 20-26 and adjacent to the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy railroad. After the war, the site became the Natrona County Municipal Airport and the land and all buildings became county property…later the name was changed to Casper-Natrona County International Airport when the airport achieved international status. The Casper Air Base was built in record time. Ground was broken in April, and six months later, on September 1, 1942, the base was officially opened. B-17 bomber crews began their Combat Crew Training School at the facility that consisted of four mile-long runways and around 400 buildings. With in six months, in the spring of 1943, the base transitioned from B-17 to B-24 crew training. Kading said, “The base was built to accommodate 20,000 men to be trained. They would come out there, and they were trained to do the last of their training in the B-17s and the B-24s because they could go around the east end of Casper Mountain and hit the zephyrs…our famous west winds…to take them right up to the sky.” By war’s end, almost 18,000 men had been trained at the Casper Army Air Base.

Not all was fun and games in learning to fly. Pilots did face risks too, as they gained experience. Flying over mountains can bring downdrafts, and turbulence, and it can make for a risky flight for the inexperienced pilot. The base had it’s share of accidents. Kading said, “The fellows hit something in the wind that they didn’t know how to handle, and they would have a plane wreck and they were lost. A lot of our pilots were in training, and we had some of our planes [that] were wrecked in other states. The soldiers’ bodies were then shipped back home to their families.” In the war years, the base was almost a third of the size of the city that was it’s host. On any given day, the base had an average of approximately 2,250 Army Air Force personnel and 800 civilians. I’m told by my Aunt Sandy Pattan that some of my aunts were among the civilians who worked there. The training class sizes varied, with as many as 6,000 in training during peak times. The men arrived in Casper by train, in newly assembled crews, each consisting of two pilots, a navigator, a bombardier, a radioman, flight engineer, and four gunners, to begin a strict regimen of training.

In one record-setting month, crews flew more than 7,500 hours at Casper Army Air Base. The remains of these activities are scattered across the high plains of Wyoming in the form of spent .50-caliber bullets, shells and links, 100-pound practice bomb fragments, and the wreckage of more than 70 aircraft. At the height of training, more than one million .50-caliber rounds and one thousand 100-pound training bombs would be expended per month. Now that, for some reason, amazes me. To think of spent bullets and parts of bombs or planes just lying around in the plains of Wyoming…just amazing, but of course, logical. One hundred forty Casper Army Air Base aviators perished in 90 plane crashes in training. Many more died later in combat. One hundred forty Casper Army Air Base aviators perished in 90 plane crashes between September 1942 and March 1945. Most of the crashes were in Wyoming, but many occurred out of state when the fliers were on longer training flights.

Most of the soldiers who came to Casper were not from Wyoming, but they embraced Wyoming and felt like their time in Casper was very special. Not only did Casper Army Air Base become a part of them forever, but they became a part of it too. Some of the soldiers wanted to show just how special the base was to them, so they decided to paint murals at the enlisted men’s club. Casper artist and art historian, Eric Wimmer, later researched the series of murals that depicted Wyoming’s history, and found that they were painted by some of the soldiers. Wimmer said, “They served for a short time, and then many soldiers were stationed at another base or sent overseas to fight in the war. This became the driving inspiration behind the concept [Cpl.] Leon Tebbetts developed for painting a set of murals in the Servicemen’s Club. He planned to give these temporary residents a history lesson on the state of Wyoming before they left.” The work began in October 1943, Tebbetts and three other soldiers with art backgrounds…JP Morgan, William Doench, and David Rosenblatt…started the series of 15 murals that included American Indians, travel on the trails in pioneer days, and other historic subjects. The murals are still there to this day.

The Casper Army Air Base closed in 1945, when the war ended. Today, the site of the old bomber base is largely intact with 90 of the original buildings still standing, including all six of the original hangars. I know that one of the barracks was moved to North Casper, because my grandfather, George Byer bought it to expand his small house to accommodate his large family of nine children. I remember playing back in that large room as a child. Visitors to the Wyoming Veterans Memorial museum in the base’s former Servicemen’s Club encounter a variety of stories: a gunnery instructor who gained his experience against the Japanese fleet during the Battle of Midway; a base commander who was known as the best machine gunner in the world; and a bomber navigator who was blown out of his B-17 and held prisoner in Germany. In addition, there are accounts of the

tragedy of the Casper Mountain bomber crash that I am certain was the crash that my then 8-year-old mother, Collene (Byer) Spencer witnessed. The base was also witness to the adventures of renowned test pilot Chuck Yeager, and saw the time that comedian Bob Hope paid a visit to the soldiers stationed there.

tragedy of the Casper Mountain bomber crash that I am certain was the crash that my then 8-year-old mother, Collene (Byer) Spencer witnessed. The base was also witness to the adventures of renowned test pilot Chuck Yeager, and saw the time that comedian Bob Hope paid a visit to the soldiers stationed there.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, everything changed in an instant. Prior to December 7, 1941, no one had guessed that the Japanese planes could actually sneak up on a place as big as Pearl Harbor…much less 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bombers) in two waves, launched from six aircraft carriers. All in all, it was enough to cause a nation to be a little freaked out…to say the least.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, everything changed in an instant. Prior to December 7, 1941, no one had guessed that the Japanese planes could actually sneak up on a place as big as Pearl Harbor…much less 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bombers) in two waves, launched from six aircraft carriers. All in all, it was enough to cause a nation to be a little freaked out…to say the least.

In the frantic weeks that followed the Pearl Harbor attack, the United States began to look at everything differently. Japanese-Americans were no longer trusted as loyal. Planes coming in to our coasts were feared…even when we knew who they were. Many Americans believed that enemy raids on the continental United States were imminent. Then, on December 9, 1941, everything came to a head when unsubstantiated reports of approaching aircraft caused a minor invasion panic in New York City that sent stock prices falling. On the West Coast, inexperienced pilots and radar men mistook fishing boats, logs, and even whales for Japanese warships and submarines. People were seeing the enemy everywhere, and everyone was tense. After US Secretary of War Henry Stimson warned that American cities should be prepared to accept “occasional blows” from enemy forces, the mood changed. Nobody was feeling okay with enemy blows, occasional or otherwise.

Then, on February 23, 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, shooting over a dozen artillery shells at an oil field and refinery. No one died in the attack, and the coast received only minor damage, but the attack marked the first time that the mainland United States had been bombed during World War II. The day after the oil field attack, people were still paranoid, and the raw nerves brought itchy trigger fingers. The events of that day aligned to produce one of the most shocking home front incidents of the war. It began on the evening of February 24, 1942, when naval intelligence instructed units on the California coast to steel themselves for a potential Japanese attack. For the next few hours, they military calmly prepared for what they perceived inevitable attack. Shortly after 2am on February 25, military radar picked up what appeared to be an enemy contact some 120 miles west of Los Angeles. Air raid sirens sounded and a citywide blackout was put into effect. Within minutes, the troops manned anti-aircraft guns and began sweeping the skies with searchlights.

Just after 3am the shooting started, triggered by reports of an unidentified object in the skies. The troops in Santa Monica unleashed a hail of anti-aircraft and .50 caliber machine gun fire. Before long, many of the city’s other coastal defense weapons had joined in. The Los Angeles Times wrote, “Powerful searchlights from countless stations stabbed the sky with brilliant probing fingers, while anti-aircraft batteries dotted the heavens with beautiful, if sinister, orange bursts of shrapnel.” The entire scene was so chaotic over the next several  minutes, that it appeared Los Angeles was indeed under attack. Still, many of those who looked skyward saw nothing, but smoke and the glare of ack-ack fire. “Imagination could have easily disclosed many shapes in the sky in the midst of that weird symphony of noise and color,” Coastal Artillery Corps Colonel John G. Murphy later wrote. “But cold detachment disclosed no planes of any type in the sky…friendly or enemy.”

minutes, that it appeared Los Angeles was indeed under attack. Still, many of those who looked skyward saw nothing, but smoke and the glare of ack-ack fire. “Imagination could have easily disclosed many shapes in the sky in the midst of that weird symphony of noise and color,” Coastal Artillery Corps Colonel John G. Murphy later wrote. “But cold detachment disclosed no planes of any type in the sky…friendly or enemy.”

Still, for many others along the coast, the threat appeared to be very real. From across the city reports poured in describing Japanese aircraft flying in formation, as well as paratroopers. There was even a claim of a Japanese plane crash landing in the streets of Hollywood. “I could barely see the planes, but they were up there all right,” a coastal artilleryman named Charles Patrick later wrote in a letter. “I could see six planes, and shells were bursting all around them. Naturally, all of us fellows were anxious to get our two-cents’ worth in and, when the command came, everybody cheered like a son of a gun.” The barrage continued for over an hour, and by the time a final “all-clear” order was given later that morning, Los Angeles’ artillery batteries had pumped over 1,400 rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition into the sky.

It was only in the light of day that the American military units made a puzzling discovery: there appeared to have been no enemy attack. “Although reports were conflicting and every effort is being made to ascertain the facts, it is clear that no bombs were dropped and no planes were shot down,” read a statement from the Army’s Western Defense Command. The counter-attack was, in reality, the whole attack. The only damage during the “battle” had come from friendly fire. Anti-aircraft shrapnel rained down across the city, shattering windows and ripping through buildings. One dud landed in a Long Beach golf course, and several residents had their homes partially destroyed by 3-inch artillery shells. There were no serious injuries from the shootout, but it was reported that at least five people had died as a result of heart attacks and car accidents that occurred during the extended blackout. In a preview of the hysteria that would soon accompany the Japanese internment, authorities also arrested some 20 Japanese-Americans for allegedly trying to signal the nonexistent aircraft.

Over the next few days, government and media outlets issued contradictory reports on what later became known as the “Battle of Los Angeles.” Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox dismissed the firefight as a false alarm brought on by “jittery nerves,” but Secretary of War Henry Stimson echoed Army brass in saying that at least 15 planes had buzzed the city. He even advanced the provocative theory that the phantom fighters might have been commercial aircraft “operated by enemy agents” hoping to strike fear into the public. Stimson later backpedaled his claims, but there was still the matter of the thousands of military personnel and civilians who  claimed to have seen aircraft in the skies over Los Angeles. According to an editorial in the New York Times, some eyewitnesses had spied “a big floating object resembling a balloon,” while others had spotted anywhere from one plane to several dozen. “The more the whole incident of the early morning of February 25 in the Los Angeles district is examined,” the article read, “the more incredible it becomes.” Politics had stepped in to put its spin on matters, and I suppose that with all that, the truth might never be known…other than no plane was found crashed in Hollywood. In reality, the whole “battle” was brought about by anxious nerves and itchy trigger fingers.

claimed to have seen aircraft in the skies over Los Angeles. According to an editorial in the New York Times, some eyewitnesses had spied “a big floating object resembling a balloon,” while others had spotted anywhere from one plane to several dozen. “The more the whole incident of the early morning of February 25 in the Los Angeles district is examined,” the article read, “the more incredible it becomes.” Politics had stepped in to put its spin on matters, and I suppose that with all that, the truth might never be known…other than no plane was found crashed in Hollywood. In reality, the whole “battle” was brought about by anxious nerves and itchy trigger fingers.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the people of the United States were justifiably nervous about the Japanese American citizens. Many of these people had family in Japan, and their loyalty was in question. No one felt safe, so on February 19, 1942, just 10 weeks later, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of any or all people from military areas “as deemed necessary or desirable.”

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the people of the United States were justifiably nervous about the Japanese American citizens. Many of these people had family in Japan, and their loyalty was in question. No one felt safe, so on February 19, 1942, just 10 weeks later, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of any or all people from military areas “as deemed necessary or desirable.”

The feeling of panic that had been simmering since the attack wasn’t going away when it came to the Japanese, or the Japanese Americans, so the military defined the entire West Coast, home to the majority of Americans of Japanese ancestry or citizenship, as a military area. What began as a plan to protect the military areas, quickly escalated, and by June, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to remote internment camps built by the United States military in scattered locations around the  country, where they would remain for the next two and a half years. Many of these Japanese Americans endured extremely difficult living conditions and poor treatment by their military guards. It wasn’t what we would expect of our own military, but it was a tense time. It almost seemed like “guilt by association” or in this case, by race. They were Japanese, and that made people wary of them…and no one was in the mood to listen to their side.

country, where they would remain for the next two and a half years. Many of these Japanese Americans endured extremely difficult living conditions and poor treatment by their military guards. It wasn’t what we would expect of our own military, but it was a tense time. It almost seemed like “guilt by association” or in this case, by race. They were Japanese, and that made people wary of them…and no one was in the mood to listen to their side.

The internment of these loyal Japanese Americans was, at the very least, unfair, and at worst, just short of criminal. It was only short of criminal because it was approved by the President of the United States. Finally, after two and a half years, United States Major General Henry C Pratt issued Public Proclamation No. 21, declaring that, effective January 2, 1945, Japanese American “evacuees” from the West Coast could return to their homes. The nightmare was over. Of  course, being over doesn’t mean that everything went immediately back to the way it was before. These people had to find new jobs and homes, because their jobs, and possibly their homes, were no longer there for them to return to.

course, being over doesn’t mean that everything went immediately back to the way it was before. These people had to find new jobs and homes, because their jobs, and possibly their homes, were no longer there for them to return to.

During the course of World War II, ten Americans were convicted of spying for Japan, but not one of them was of Japanese ancestry, which is disgusting…not that no Japanese Americans were part of that, but that any American would betray their country in this way. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill to recompense each surviving internee with a tax-free check for $20,000 and an apology from the United States government.