outlaws

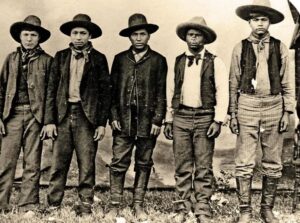

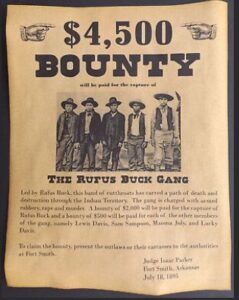

The Rufus Buck Gang was a multiracial group of African American and Native American outlaws, notorious for a series of murders, robberies, and assaults. They were a brutal bunch, and they considered anyone fair game…men, women, and children. Headed up by Rufus Buck, the gang also consisted of Lucky Davis, Maoma July, Lewis Davis, and Sam Sampson. The men had no scruples and no respect for life. Their criminal activities took place in the Indian Territory of the Arkansas-Oklahoma area from July 30, 1895, through August 4, 1896.

The Rufus Buck Gang was a multiracial group of African American and Native American outlaws, notorious for a series of murders, robberies, and assaults. They were a brutal bunch, and they considered anyone fair game…men, women, and children. Headed up by Rufus Buck, the gang also consisted of Lucky Davis, Maoma July, Lewis Davis, and Sam Sampson. The men had no scruples and no respect for life. Their criminal activities took place in the Indian Territory of the Arkansas-Oklahoma area from July 30, 1895, through August 4, 1896.

Before they started their crime spree, the gang began while staying in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, by building up a small stockpile of weapons. Then, on  July 30, 1895, they killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. With the lawman out of the way, they began holding up various stores and ranches in the Fort Smith area over the next two weeks. Then, the brutality began. During one robbery, a salesman named Callahan, after being robbed, was offered a chance to escape…if he could outrun the gang. Callahan was an elderly man, and they thought an easy mark, but he successfully escaped, which angered the men, so the gang killed his assistant in frustration. At least two female victims who were raped by the gang died of their injuries.

July 30, 1895, they killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. With the lawman out of the way, they began holding up various stores and ranches in the Fort Smith area over the next two weeks. Then, the brutality began. During one robbery, a salesman named Callahan, after being robbed, was offered a chance to escape…if he could outrun the gang. Callahan was an elderly man, and they thought an easy mark, but he successfully escaped, which angered the men, so the gang killed his assistant in frustration. At least two female victims who were raped by the gang died of their injuries.

In all, the gang, Killed Deputy US Marshal John Garrett. Then on July 31, 1895, they came across a white man and his daughter in a wagon, the gang held the man at gunpoint and took the girl. They killed a black boy and beat Ben Callahan until they mistakenly believed he was dead, then took Callahan’s boots, money, and saddle. They robbed the country stores of West and J Norrberg at Orket, Oklahoma. They murdered two white women and a 14-year-old girl. Then, on August 4th, they raped a Mrs Hassen near Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Hassen and two of three other female victims of the gang…a Miss Ayres and an Indian girl  near Sapulpa, all died; and a fourth victim, Mrs Wilson recovered from her injuries. Continuing attacks on both local settlers and Creek indiscriminately, the gang was finally captured outside Muskogee by a combined force of lawmen and Indian police of the Creek Light Horse, led by Marshal S Morton Rutherford, on August 10. While the Creek Light Horse forces wanted to hold the gang for trial, the men were brought before “Hanging” Judge Isaac Parker. The judge twice sentenced them to death, the first sentence not being carried out pending an ultimately unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court. They were hanged on July 1, 1896 at 1pm at Fort Smith.

near Sapulpa, all died; and a fourth victim, Mrs Wilson recovered from her injuries. Continuing attacks on both local settlers and Creek indiscriminately, the gang was finally captured outside Muskogee by a combined force of lawmen and Indian police of the Creek Light Horse, led by Marshal S Morton Rutherford, on August 10. While the Creek Light Horse forces wanted to hold the gang for trial, the men were brought before “Hanging” Judge Isaac Parker. The judge twice sentenced them to death, the first sentence not being carried out pending an ultimately unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court. They were hanged on July 1, 1896 at 1pm at Fort Smith.

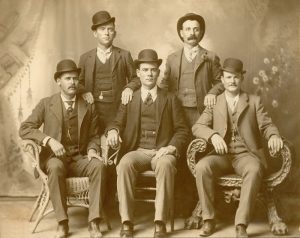

George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb was the first member of the infamous Dalton Gang…an outlaw gang in the Old West. Newcomb was born in 1866 near Fort Scott, Kansas. The Newcomb family was poor, and he began working as a cowboy at the age of twelve. Newcomb’s first job was on the “Long S Ranch” owned by CC Slaughter. By 1892, he had drifted into the Oklahoma Territory, where he first met Bill Doolin. Newcomb would meet up with Bill Doolin again, in a deadly way.

George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb was the first member of the infamous Dalton Gang…an outlaw gang in the Old West. Newcomb was born in 1866 near Fort Scott, Kansas. The Newcomb family was poor, and he began working as a cowboy at the age of twelve. Newcomb’s first job was on the “Long S Ranch” owned by CC Slaughter. By 1892, he had drifted into the Oklahoma Territory, where he first met Bill Doolin. Newcomb would meet up with Bill Doolin again, in a deadly way.

As a part of the Dalton Gang, Newcomb met up with Doolin and also met Charley Pierce, who were also members. The three men took part in the botched train robbery in Adair, Oklahoma Territory, on July 15, 1892. During the robbery, two guards and two townsmen, both doctors, were wounded. One of the doctors died the next day. Doolin, Newcomb, and Pierce complained that Bob was unfairly dividing the money fairly amongst the gang. They left in a huff, but later returned. It was at this point that Bob Dalton told Doolin, Newcomb, and Pierce that he no longer needed them. Dalton said that Newcomb was “too wild” for his gang, and Dalton left. Doolin and his friends returned to their hideout in Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory. On October 5, in Coffeyville, Kansas, the remaining members of the Dalton Gang were killed…except Emmett who survived despite being shot 27 times.  I suppose it was fortunate for Newcomb, Doolin, and Pierce that they were no longer part of the gang.

I suppose it was fortunate for Newcomb, Doolin, and Pierce that they were no longer part of the gang.

In 1893, Doolin organized his own gang from the remains of the original Dalton Gang, with Newcomb as a member, calling them the Wild Bunch. Bill Dalton later also joined the group and they became known as the Doolin-Dalton Gang. Newcomb began a romantic relationship with a 14 year old girl named Rose Dunn. She had four brothers who were outlaws and knew Newcomb. They would later become bounty hunters, calling themselves the Dunn Brothers. By 1895, Newcomb was a fugitive with a $5,000 reward on him, dead or alive. Rose Dunn traveled with him, since she could easily go into a town to purchase supplies, and no one knew that she was a part of the gang. This was the perfect plan to keep the gang hidden.

The gang often hung out in the town of Ingalls, Oklahoma. In those days, numerous outlaw gangs of the day took refuge there, and oddly, local residents often defended the outlaws and assisted in hiding them from lawmen. This was mostly due to the outlaws contributing greatly to the local economy. In one shootout with lawmen in Ingalls, called the Battle of Ingalls, three lawmen and three outlaws were shot. After several  shootouts with lawmen, Newcomb fled with outlaw Charley Pierce to a hideout near Norman, Oklahoma, both of them wounded in the Ingalls shootout with US Marshals.

shootouts with lawmen, Newcomb fled with outlaw Charley Pierce to a hideout near Norman, Oklahoma, both of them wounded in the Ingalls shootout with US Marshals.

On May 2, 1895, Newcomb and Pierce rode up to the Dunn ranch, possibly to visit Rose. As soon as they dismounted, her brothers opened fire, dropping both outlaws. The next day, the Dunn brothers had loaded the two bodies into their wagon and were driving it into town to collect the reward, when Newcomb suddenly moaned and asked for water, to which one of the brothers responded with another bullet. I guess the bounty on their heads outweighed the friendship the Dunn Brothers had previously with the Wild Bunch.

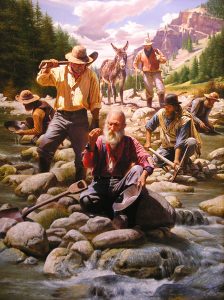

After the discovery of gold in California, people went crazy…mad really for gold. For twenty years, in fact, all the West was mad for gold. People packed up their lives, and headed west, hoping to dig their fortune out of the California dirt. At first, the people heading west were mostly men, but there were families that went too. It didn’t really matter who it was, when it came to gold, people were willing to fight to the death for what was theirs, or for what they wanted. Greed was the word of the day, and it was a disease that everyone in California had.

After the discovery of gold in California, people went crazy…mad really for gold. For twenty years, in fact, all the West was mad for gold. People packed up their lives, and headed west, hoping to dig their fortune out of the California dirt. At first, the people heading west were mostly men, but there were families that went too. It didn’t really matter who it was, when it came to gold, people were willing to fight to the death for what was theirs, or for what they wanted. Greed was the word of the day, and it was a disease that everyone in California had.

The Gold Rush brought honest citizens and outlaws alike to California. People had to be on guard at all times. If someone struck gold, they were an immediate target for anyone willing to steal their gold, or even to kill for it. The mad rush for gold soon spread to other areas of the United States. The gold-hunters, no longer content with California, began to prospect lower Oregon, upper Idaho, and Western Montana too. They figured that if one place had gold, why wouldn’t another place have it too. And with the slightest discovery, came the craziness of Gold Dust Fever.

With Gold Fever came the sinister figure of the trained desperado, the professional bad man. The business of  being an outlaw was turned into one highly organized profession that was relatively safe and extremely lucrative. There was wealth to be had for the asking or the taking, and these men, and sometimes women, were willing. Each miner had his buckskin purse filled with native gold. This dust was like all other dust. It could not be traced nor identified; and the old saying, ”’Twas mine, ’tis his,” might here of all places in the world most easily become true. There were no checks, drafts, or currency, as we know it now. The normal means by which civilized men keep a record of their property transactions, were unknown. The gold scales established the only currency, and each man was his own banker, obliged to be his own peace officer and the defender of his own property. It was a wild world. It was a world mad for gold.

being an outlaw was turned into one highly organized profession that was relatively safe and extremely lucrative. There was wealth to be had for the asking or the taking, and these men, and sometimes women, were willing. Each miner had his buckskin purse filled with native gold. This dust was like all other dust. It could not be traced nor identified; and the old saying, ”’Twas mine, ’tis his,” might here of all places in the world most easily become true. There were no checks, drafts, or currency, as we know it now. The normal means by which civilized men keep a record of their property transactions, were unknown. The gold scales established the only currency, and each man was his own banker, obliged to be his own peace officer and the defender of his own property. It was a wild world. It was a world mad for gold.

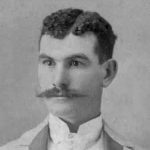

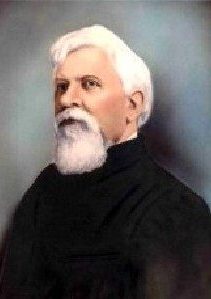

The Indian Territory, which is now Oklahoma, in 1875, was populated by cattle and horse thieves, whiskey peddlers, and bandits who sought refuge in the untamed territory that was free of a “White Man’s Court.” There was one court with jurisdiction over Indian Territory was the U.S. Court for the Western District of Arkansas located in Fort Smith, Arkansas, which was situated on the border of Western Arkansas and Indian Territory. Judge Isaac Parker, who was often called the “Hanging Judge,” from Fort Smith, Arkansas ruled over the lawless land of Indian Territory in the late 1800s. He was determined to stop the pollution of the Indian Territory that was the outlaws who thought they could outrun the law.

The Indian Territory, which is now Oklahoma, in 1875, was populated by cattle and horse thieves, whiskey peddlers, and bandits who sought refuge in the untamed territory that was free of a “White Man’s Court.” There was one court with jurisdiction over Indian Territory was the U.S. Court for the Western District of Arkansas located in Fort Smith, Arkansas, which was situated on the border of Western Arkansas and Indian Territory. Judge Isaac Parker, who was often called the “Hanging Judge,” from Fort Smith, Arkansas ruled over the lawless land of Indian Territory in the late 1800s. He was determined to stop the pollution of the Indian Territory that was the outlaws who thought they could outrun the law.

Judge Isaac Parker was born in a log cabin outside Barnesville, Belmont County, Ohio on October 15, 1838. The youngest son of Joseph and Jane Parker. As a boy, Isaac helped out on the farm, but never really cared for that type of work. He attended the Breeze hill primary school and then the Barnesville Classical Institute. Knowing he wanted more, he decided to go for a higher education. To help pay for it, he taught students in a country primary school. When he was 17 he decided to study law, his legal training consisting of a combination of apprenticeship and self study. Reading law with a Barnesville attorney, he passed the Ohio bar exam in 1859 at the age of 21. During this period of his life, he met and married Mary O’Toole and the couple had two sons, Charles and James. Over the years, Parker built a reputation for being an honest lawyer and a much respected leader of the community.

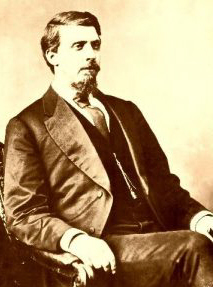

After Parker passed the bar, he decided to head west, ending up in Saint Joseph, Missouri a bustling Missouri River port town. He went to work for his uncle, D.E. Shannon, becoming a partner in the Shannon and Branch legal firm. By 1861, he was working on his own in both the municipal and county criminal courts. In April of 1861, he won the election as City Attorney. He was re-elected to the post for the next two years. In 1864,  Isaac Parker ran for county prosecutor of the Ninth Missouri Judicial District and in the fall of that same year, he served as a member of the Electoral College, casting his vote for Abraham Lincoln. During a political career that included a six-year term as judge of the Twelfth Missouri Circuit in 1868, Parker would soon gain the experience that he would later use as the ruling Judge over the Indian Territory.

Isaac Parker ran for county prosecutor of the Ninth Missouri Judicial District and in the fall of that same year, he served as a member of the Electoral College, casting his vote for Abraham Lincoln. During a political career that included a six-year term as judge of the Twelfth Missouri Circuit in 1868, Parker would soon gain the experience that he would later use as the ruling Judge over the Indian Territory.

After the Civil War, the number of outlaws had grown, wrecking the relative peace of the five civilized tribes that lived in Indian Territory. By the time Parker arrived at Fort Smith, the Indian Territory had become known as a very bad place, where outlaws thought the laws did not apply to them and terror reigned. Parker replaced Judge William Story, whose tenure had been marred by corruption, after arriving in Fort Smith on May 4, 1875. At the age of 36, Judge Parker was the youngest Federal judge in the West. Holding court for the first time on May 10, 1875, eight men were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Judge Parker held court six days a week, often up to ten hours each day and tried 91 defendants in his first eight weeks on the bench. He was determined to clean up the Indian Territory, single handedly if necessary. In that first summer, eighteen persons came before him charged with murder and 15 were convicted. Eight of them were sentenced to die on the gallows on September 3, 1875. However, only six would be executed as one was killed trying to escape and a second had his sentence commuted to life in prison because of his young age.

The day of the September 3, 1875 hanging was a media circus, and because of all the attention, everyone knew that the once corrupt court was functioning properly again. Parker’s critics dubbed him the “Hanging Judge” and called his court the “Court of the Damned.” They thought Judge Parker was too harsh. The Fort  Smith Independent was the first newspaper to report the event on September 3, 1875 with the large column heading reading: “Execution Day!!” Other newspapers around the country reported the event a day later. These press reports shocked people throughout the nation. “Cool Destruction of Six Human Lives by Legal Process” screamed the headlines. Of the six felons, three were white, two were Native American and one was black. When the preliminaries were over, the six were lined up on the scaffold while executioner George Maledon adjusted the nooses around their necks. The trap was sprung all six died at once at the end of the ropes. The event solidified Judge Parker’s nickname for all time. In 21 years on the bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases, 344 of which were capital crimes. 9,454 cases resulted in guilty pleas or convictions. Over the years, Judge Parker sentenced 160 men to death by hanging, though only 79 of them were actually hanged. The rest died in jail, appealed or were pardoned. Judge Parker died on November 17, 1896.

Smith Independent was the first newspaper to report the event on September 3, 1875 with the large column heading reading: “Execution Day!!” Other newspapers around the country reported the event a day later. These press reports shocked people throughout the nation. “Cool Destruction of Six Human Lives by Legal Process” screamed the headlines. Of the six felons, three were white, two were Native American and one was black. When the preliminaries were over, the six were lined up on the scaffold while executioner George Maledon adjusted the nooses around their necks. The trap was sprung all six died at once at the end of the ropes. The event solidified Judge Parker’s nickname for all time. In 21 years on the bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases, 344 of which were capital crimes. 9,454 cases resulted in guilty pleas or convictions. Over the years, Judge Parker sentenced 160 men to death by hanging, though only 79 of them were actually hanged. The rest died in jail, appealed or were pardoned. Judge Parker died on November 17, 1896.

Little is known about the early life of William Coe, always known as “Captain” Bill Coe, except that he was a southern boy and worked as a carpenter and stonemason…until he turned to a life of crime, that is. It is believed that he fought with the Confederates during the Civil War, which is probably where he came to be known as the “Captain,” but there is no solid poof of this.

Little is known about the early life of William Coe, always known as “Captain” Bill Coe, except that he was a southern boy and worked as a carpenter and stonemason…until he turned to a life of crime, that is. It is believed that he fought with the Confederates during the Civil War, which is probably where he came to be known as the “Captain,” but there is no solid poof of this.

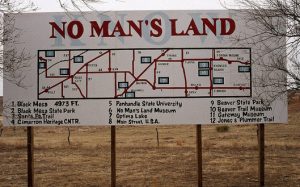

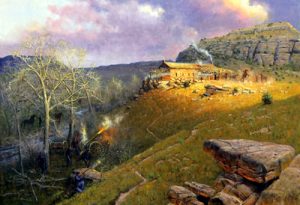

“Captain” Bill Coe arrived in the Oklahoma Panhandle about 1864, having decided to settle in that area. The area was referred to as “No Man’s Land”t that time. The strip of land, measuring some 35 miles wide by 168 miles long, was not included in any state and therefore left without any law and order. It was a haven for outlaws for years , and William Coe took advantage of that situation. Along a long high ridge jutting southwest from a large mesa near the town of Kenton, Oklahoma, “Captain” Coe built a “fortress” to protect himself and his gang of some 30 to 50 members, who primarily rustled cattle, horses, sheep, and mules. Coe’s headquarters, made of rock walls that were about three feet thick. There were portholes for protection rather than windows, as well as a fully stocked bar, living quarters for his men, and a number of ladies of the evening for their entertainment. Coe’s fortress became known as “Robber’s Roost.”

These men raided ranches and military installations from Fort Union, New Mexico to the south, Taos, New Mexico to the west, and as far north as Denver, Colorado to make their living. They also robbed freight caravans traveling along the Santa Fe Trail, as well as area ranches. Coe’s gang hid the stock in a canyon about five miles northwest of their hide-out. They built a fully equipped blacksmith shop, which contained all the tools necessary to maintain the herds, as well as changing the brands. When all hint of the previous owners were removed, the gang then moved the herds into Missouri or Kansas to sell. They got away with their lawlessness for several years…then they made a major mistake when they raided a large sheep ranch in Las Vegas, New Mexico in 1867, killing two men before making off with the herd to Pueblo, Colorado. They had been wanted men before, but these murders put Coe and his men on the “wanted list” like never before. Soon the U.S. Army from Fort Lyon, Colorado were pursuing them.

The Army attacked the Robber’s Roost fortress with a cannon. The walls crumbled like pebbles. The attack killed and wounded several of the outlaws. Though Coe and others were able to escape, several outlaws that weren’t killed in the battle were hanged on the spot, while others were arrested and taken back to Colorado. Coe continued his crimes and his freedom for about a year, hiding out in a small, now abandoned settlement of Madison, New Mexico, near Folsom. Then, while he was sleeping in a woman’s bunkhouse, her 14-year-old son rode from the ranch and contacted area soldiers, who soon returned and arrested Coe. The fugitive was then taken to Pueblo, Colorado to await trial and along the way, allegedly said, “I never figured to be “outgeneraled” by a woman, a pony, and a boy.”

Before Coe could be brought to trial, vigilantes took matters into their own hands on the evening of July 20, 1868. They forcibly removed him from the jail, loaded him into a wagon, and hung him on a cottonwood tree on the bank of Fountain Creek, while he was still handcuffed and shackled. The next day, his body was discovered and buried under the tree that he was hanged from. Years later, when a new road was being built in the vicinity of Fourth Street in Pueblo, workers found the skeletal remains of what is believed to have been Coe’s.

When we think of the outlaws of the old west, the term “gunfighter” or “gunslinger” were not the terms used to describe those men, or even the lawmen that some of them became upon changing their ways. They were actually originally called pistoleers, shootists, bad men, or one we do know…gunmen. That being said, Bat Masterson, who was a noted gunfighter himself, who later became a writer for the New York Morning Telegraph, sometimes referred to them as “gunfighters,” but, more often as “man killers.”

When we think of the outlaws of the old west, the term “gunfighter” or “gunslinger” were not the terms used to describe those men, or even the lawmen that some of them became upon changing their ways. They were actually originally called pistoleers, shootists, bad men, or one we do know…gunmen. That being said, Bat Masterson, who was a noted gunfighter himself, who later became a writer for the New York Morning Telegraph, sometimes referred to them as “gunfighters,” but, more often as “man killers.”

I suppose that Bat Masterson was probably the one who coined the term “gunfighter” in the first place, but many people from that era must have thought it an odd term to use. Still, if you heard an outlaw called a pistoleers, wouldn’t you have wondered what that was supposed to be? I would have, but then I would have looked it up and found that a pistoleers was “a soldier armed with a pistol.” That would have made no sense to me either, but in reality, some of the outlaws were soldiers who didn’t want to fight for a cause they didn’t believe in, so their deserted and headed west, so I guess they could have been pistoleers.

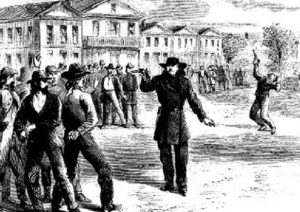

Another “movie mix-up” that happened is that in the old west, pistoleers or shootists didn’t squarely face off with each other from a distance in a dusty street, like they would like us to believe. In reality, the “real” gunfights of the Old West were rarely that “civilized.” Many fought in the many range wars and feuds of the Old West, which were far more common that the “stand-off” gunfight. Most of these were fought over land or water rights, some were political, and others were simply “old Hatfield-McCoy” style differences between families or in lifestyles. These people fought from the protection of anything available like a watering trough, a wall, building, or even a horse. Of those that more easily fit the perception of the “gunfighter,” you would find that they didn’t kill anywhere near the number of men they are credited with on television. In many instances their reputations stemmed from one particular fight, and the rumors grew from there, making people think they were that good. In other cases, self-promotion led people to believe they were lethal shootists, such was the case with Wyatt Earp and Wild Bill Hickok.

There were other, lesser known shootists, who actually saw just as much, if not more action than their well-known counterparts. Men like Ben Thompson, Tom Horn, Kid Curry, Timothy Courtright, King Fisher, Scott  Cooley, Clay Allison, and Dallas Stoudenmire, just to name a few, were often not credited for nearly the shooting ability of the well known shooters. Often these gunfighters, whose occupations ranged from lawmen, to cowboys, ranchers, gamblers, farmers, teamsters, bounty hunters, and outlaws, were violent men who could move quickly from fighting one side of the law to the other, depending on what suited them best at the time. Though many of these gunman died of “natural causes,” many died violently in gunfights, lynchings, or legal executions. The average age of death was about 35. However, of those gunman who used their skills on the side of the law, they would persistently live longer lives than those that lived a life of crime.

Cooley, Clay Allison, and Dallas Stoudenmire, just to name a few, were often not credited for nearly the shooting ability of the well known shooters. Often these gunfighters, whose occupations ranged from lawmen, to cowboys, ranchers, gamblers, farmers, teamsters, bounty hunters, and outlaws, were violent men who could move quickly from fighting one side of the law to the other, depending on what suited them best at the time. Though many of these gunman died of “natural causes,” many died violently in gunfights, lynchings, or legal executions. The average age of death was about 35. However, of those gunman who used their skills on the side of the law, they would persistently live longer lives than those that lived a life of crime.

When we think of the Old West, cowboys, Indians, and outlaws come to mind…not to mention showdowns, or what might have been known as a duel, in years gone by. In reality, showdowns were not all that common…no matter what Hollywood tries to tell you. The men and women who went west were a tough bunch. In the beginning, it was mostly men who went west, and since there was no law in the West, altercations were bound to happen. Still, altercations that led to a showdown were not all that common. Rather than coolly confronting each other on a dusty street in a deadly game of quick draw, most men began shooting at each other in drunken brawls or spontaneous arguments. Ambushes and cowardly attacks were far more common than noble showdowns, but those who took the noble approach were far more respected.

When we think of the Old West, cowboys, Indians, and outlaws come to mind…not to mention showdowns, or what might have been known as a duel, in years gone by. In reality, showdowns were not all that common…no matter what Hollywood tries to tell you. The men and women who went west were a tough bunch. In the beginning, it was mostly men who went west, and since there was no law in the West, altercations were bound to happen. Still, altercations that led to a showdown were not all that common. Rather than coolly confronting each other on a dusty street in a deadly game of quick draw, most men began shooting at each other in drunken brawls or spontaneous arguments. Ambushes and cowardly attacks were far more common than noble showdowns, but those who took the noble approach were far more respected.

Southern emigrants brought to the West a crude form of the “code duello,” a highly formalized means of solving disputes between gentlemen with swords or guns that had its origins in European chivalry. Similar to the duels of times past, they thought it would bring some form of civility to the West. The duel influenced the informal western code of what constituted a legitimate and legal gun battle. Duels were not used to for very long. In fact, by the second half of the 19th century, few Americans still fought duels to solve their problems.  The western code required that a man resort to his six-gun only in defense of his honor or life, and only if his opponent was also armed. Also, a western jury was unlikely to convict a man in a shooting provided witnesses testified that his opponent had been the aggressor.

The western code required that a man resort to his six-gun only in defense of his honor or life, and only if his opponent was also armed. Also, a western jury was unlikely to convict a man in a shooting provided witnesses testified that his opponent had been the aggressor.

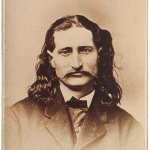

In what is thought to be the first western duel, Wild Bill Hickok, killed Davis Tutt on July 21, 1865. Hickok was a skilled gunman with a formidable reputation, who was eking out a living as a professional gambler in Springfield, Missouri. He quarreled with Tutt, a former Union soldier, but it is unclear what caused the dispute. Some people say it was over a card game while others say they fought over a woman. Whatever the cause, the two men agreed to a duel. The showdown took place the following day with crowd of onlookers watching as Hickok and Tutt confronted each other from opposite sides of the town square. When Tutt was about 75 yards away, Hickok shouted, “Don’t come any closer, Dave.” Tutt nervously drew his revolver and fired a shot that went wild. Hickok, by contrast, remained cool. He steadied his own revolver in his left hand and shot Tutt dead with a bullet through the chest. Hickok immediately turn and threatened Tutt’s friends…should they try to avenge his death.

Having adhered to the code of the West, Hickok was acquitted of manslaughter charges. Nevertheless, those were rough times, and just eleven years later, Hickok died in a fashion far more typical of the violence of the day. A young gunslinger shot him in the back of the head while he played cards. Legend says that the hand Hickok was holding at the time of his death was two pair…black aces and black eights. The hand would forever be known as the “dead man’s hand.” Jack McCall shot Hickok from behind as he played poker at Nuttal & Mann’s Saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory on August 2, 1876. In one shooting is honor, and in another is a dishonor. McCall was executed for the murder on March 1, 1877.

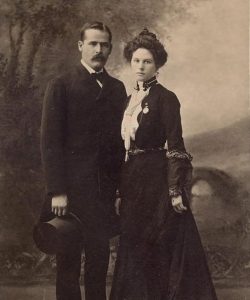

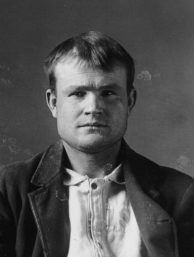

Over the years, many have speculated about the validity of the death of famous people, among them, Elvis Presley. For some unknown reason, people just cant believe, for whatever reason, that someone famous is dead. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were legendary outlaws who robbed trains, payroll couriers, and banks. When the law got too close to them, they took off for Bolivia. It wasn’t a plan that fared well…or was it? Robert Leroy Parker was born April 13, 1866, in Beaver, Utah. As a bandit, he used the alias Butch Cassidy. Harry Alonzo Longabaugh born in Mont Clare, Pennsylvania in 1867, was better known as Butch Cassidy’s sidekick and partner in crime, the Sundance Kid. The two of them had an illustrious criminal career, but as with all criminal careers, at some point mistakes are made, or they meet their match in a lawman who bests them, with a gun or their abilities as a detective. A part of the Wild Bunch, the careers of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were shrouded in mystery, but that mystery pales by comparison to their deaths. After making their escape to Argentina, and then to Bolivia, Cassidy, the Kid, and girlfriend, Etta Place thought that the small town of San Vicente would be an easy target for their crimes.

Over the years, many have speculated about the validity of the death of famous people, among them, Elvis Presley. For some unknown reason, people just cant believe, for whatever reason, that someone famous is dead. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were legendary outlaws who robbed trains, payroll couriers, and banks. When the law got too close to them, they took off for Bolivia. It wasn’t a plan that fared well…or was it? Robert Leroy Parker was born April 13, 1866, in Beaver, Utah. As a bandit, he used the alias Butch Cassidy. Harry Alonzo Longabaugh born in Mont Clare, Pennsylvania in 1867, was better known as Butch Cassidy’s sidekick and partner in crime, the Sundance Kid. The two of them had an illustrious criminal career, but as with all criminal careers, at some point mistakes are made, or they meet their match in a lawman who bests them, with a gun or their abilities as a detective. A part of the Wild Bunch, the careers of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were shrouded in mystery, but that mystery pales by comparison to their deaths. After making their escape to Argentina, and then to Bolivia, Cassidy, the Kid, and girlfriend, Etta Place thought that the small town of San Vicente would be an easy target for their crimes.

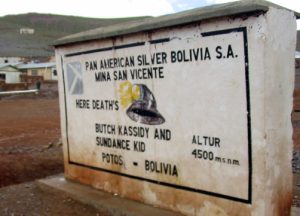

As courier for the Aramayo, Francke and Cia mining company, Carlos Pero was riding his mule up a rugged trail high in the Andes Mountains on the morning of November 4, 1908. He was completely unaware that his every move was being watched. Pero later said that after cresting a hill, he was “surprised by two Yankees, whose faces were covered with bandanas and whose rifles were cocked and ready to fire.” The pair of masked bandits robbed the courier of the company’s payroll and then disappeared into the desolation of southern Bolivia, but that was not to be the end of it. Three days later, four Bolivian officers cornered a pair of Americans suspected of being the bandits in a rented house, in the dusty village of San Vicente. The Pinkerton Detective Agency, which had long been trailing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and had warned banks across South America to be on the lookout for them, because they had fled there from the United States in 1901. It was  reported that the two Americans holed up in San Vicente were them. As a Bolivian soldier approached the hideout, the Americans shot him dead. A brief exchange of gunfire ensued. When it was over, San Vicente mayor Cleto Bellot reported hearing “three screams of desperation” followed by two gunshots from inside the house. When the Bolivian authorities cautiously entered the hideout the following morning, they found the bodies of the two foreigners.

reported that the two Americans holed up in San Vicente were them. As a Bolivian soldier approached the hideout, the Americans shot him dead. A brief exchange of gunfire ensued. When it was over, San Vicente mayor Cleto Bellot reported hearing “three screams of desperation” followed by two gunshots from inside the house. When the Bolivian authorities cautiously entered the hideout the following morning, they found the bodies of the two foreigners.

For decades, Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows, husband and wife researchers scoured South American archives and police reports trying to track down the true story of what happened to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a saga that Meadows detailed in her book “Digging up Butch and Sundance.” While the paper trail pointed to their deaths in Bolivia, conclusive evidence as to the identities of the bandits killed in San Vicente in November 1908 rested under the ground of the village’s cemetery. The researchers enlisted the help of Clyde Snow, the renowned forensic anthropologist who had conclusively identified the remains of Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele. They received permission from Bolivian authorities to exhume the robbers’ bodies. Guided to their purported grave by an elderly villager whose father had reportedly witnessed the shootout, they opened the graves in 1991. Inside they found a skeleton of one man, and a piece of a skull from another. After a detailed forensic analysis and a comparison of DNA to the relatives of Cassidy and Longabaugh, Snow found there was no match. The skeleton was instead likely to have been that of a German miner named Gustav Zimmer who had worked in the area. It’s possible that the bodies of the iconic outlaws remain buried elsewhere in the San Vicente cemetery or even elsewhere in the country, but with no conclusive proof as to the whereabouts of the bodies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, their ultimate fate remains a mystery.

With no conclusive evidence to confirm the deaths of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the rumors flew, that the pair had once again eluded the long arm of the law, and sightings of the duo in South America, Mexico and the United States continued for decades to come. Family members fueled the stories by insisting that the men had never been killed and instead returned to the United States to live into old age. Cassidy’s sister, Lula Parker Betenson, wrote in her 1975 book “Butch Cassidy, My Brother” that the outlaw had returned to the family ranch in Circleville, Utah, in 1925 to visit his ailing father and attend a family wedding. According to Betenson, Cassidy told the family that a friend of his had planted the story that one of the men killed in Bolivia was him so that he would no longer be pursued. She claimed that Cassidy lived in the state of Washington under an alias until his death in 1937. Betenson said her brother was buried in an unmarked grave in a location that was kept a family secret.

Back in the day, girls pretty much wore dresses all the time. In fact, girls wearing pants were considered…risque, loose, or maybe backward. By the mid 1900’s things had changed to a degree, and pants were ok for certain activities. Nevertheless, many girls just didn’t own pants, so they continued to wear dresses for activities we would consider it to be inappropriate to wear dresses for today.

Back in the day, girls pretty much wore dresses all the time. In fact, girls wearing pants were considered…risque, loose, or maybe backward. By the mid 1900’s things had changed to a degree, and pants were ok for certain activities. Nevertheless, many girls just didn’t own pants, so they continued to wear dresses for activities we would consider it to be inappropriate to wear dresses for today.

One of those activities was horseback riding. Early on when the women started riding horses, it was considered taboo for them to straddle a horse. People really thought of them as having very low moral standards. That was when the side saddle came about. The big problem with that was that the horse had to be very well trained, because the woman had a lot less control over the horse when it was side saddle. To me, side saddle seems like it would be an extremely awkward way to ride. I think it would feel like you were hanging on a wall…much like a painting.

Then, when people moved out west, they began to leave those civilized ideas of the east  behind them. It was a necessity, because many of the horses were wild and then tamed, and people lived on homesteads the were a long way from their homes. And then, of course, was the fact that sometimes you had to outrun the dangers of the region, like Indians, wild animals, and outlaws. Running from danger was no time to be a lady in a side saddle…if you wanted to live, that is. Watching the old westerns, I remember thinking how funny it looked to have those long dresses draped over the back end of a horse.

behind them. It was a necessity, because many of the horses were wild and then tamed, and people lived on homesteads the were a long way from their homes. And then, of course, was the fact that sometimes you had to outrun the dangers of the region, like Indians, wild animals, and outlaws. Running from danger was no time to be a lady in a side saddle…if you wanted to live, that is. Watching the old westerns, I remember thinking how funny it looked to have those long dresses draped over the back end of a horse.

Now, of course, many women rarely wear a dress at all, much less to ride a horse. Women have found that it is far more comfortable to live most of their lives in jeans, so dresses are reserved for special occasions. Nevertheless, there was a time, a very different time, when women wouldn’t have ever considered things like wearing men’s pants or straddling a horse.

When I was a kid, I thought that mostly men carried or used guns…probably because I watched too many old Western shows in which the women were portrayed as weak and needing protection. The only women who carried or used guns were looked upon like…well less than womanly…I mean most of those women were outlaws who wore mens pants for Pete’s sake. The only time the women in the Old West movies used a gun was when there was no other choice, and no man around to save her, and even then, she usually lost the fight, unless she was the main star. Needless to say it was probably a pretty warped view of the women of the West on my part.

When I was a kid, I thought that mostly men carried or used guns…probably because I watched too many old Western shows in which the women were portrayed as weak and needing protection. The only women who carried or used guns were looked upon like…well less than womanly…I mean most of those women were outlaws who wore mens pants for Pete’s sake. The only time the women in the Old West movies used a gun was when there was no other choice, and no man around to save her, and even then, she usually lost the fight, unless she was the main star. Needless to say it was probably a pretty warped view of the women of the West on my part.

Of course, now that I am older, I know that this portrayal was very incorrect. The women of the Old West were a tough lot. They might have been looked at by people from back East as less than womanly, but times were changing, and women had to be tough to survive in the Old West. The men who came to settle the West needed women who could work side by side with them and who were tough enough to take care of themselves when the men were away. Only the most determined women were going to be able to make it here. Things have changed some now. There are probably as many women back east that can handle a gun as there are women out west who can. Womem are active in many careers that require them to carry a gun on a regular basis, and be tough enough to go up against the men they must to survive, whether it be in war or law enforcement.

My grandmother was one of those women who was able to handle a gun, and while they never moved as far west as my dad and my aunts did, they did not live in the east either. Wisconsin and Minnesota were wilder places back then, and even in North Dakota in the early 1900’s there was need for a gun. Of course, mostly the guns were used for hunting, but had the need ever arisen, my grandmother would have taken on man or beast to protect her children. She was one tough lady, who worked hard on the farm, and raised her children right, and I am very proud of all she did. I only wish I had been able to know her, but I was only 3 months old when she left us on July 11, 1956. I look forward to getting to know her in Heaven, because I’m sure she will have some stories to tell.