japanese

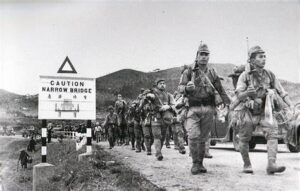

When a soldier is told to guard an area for his country, he does just that, but on this occasion, this job of “guarding” an area, or an island in this case, was taken to extremes. For a time, the Allies struggled against the Japanese, but by 1945, the tide of World War II had turned decisively against Japan. The Japanese got really nervous as the Americans advanced across the Pacific, drawing ever closer to the Japanese home islands. The American strategists set their sights on Iwo Jima, a small volcanic island about 750 miles south of Tokyo. They saw it as a suitable staging area for an eventual invasion of Japan. Of course, the Japanese were very aware of the threat posed by Iwo Jima landing in American hands. So, they knew they had to garrison the island.

When a soldier is told to guard an area for his country, he does just that, but on this occasion, this job of “guarding” an area, or an island in this case, was taken to extremes. For a time, the Allies struggled against the Japanese, but by 1945, the tide of World War II had turned decisively against Japan. The Japanese got really nervous as the Americans advanced across the Pacific, drawing ever closer to the Japanese home islands. The American strategists set their sights on Iwo Jima, a small volcanic island about 750 miles south of Tokyo. They saw it as a suitable staging area for an eventual invasion of Japan. Of course, the Japanese were very aware of the threat posed by Iwo Jima landing in American hands. So, they knew they had to garrison the island.

Ymakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki were two Japanese machine gunners assigned to the island’s garrison. I can only imagine how they must have felt, knowing that the attack was imminent, and that they could only sit and wait for it. In February of 1945, Iwo Jima was invaded in one of the fiercest and bloodiest battles of the entire Pacific War. The Japanese soldiers fought frantically, almost to the last man. Japanese soldiers were taught that it was more honorable to die that survive, if they lost the war. They were taught that rather than surrender, the honorable thing to do was to commit suicide, so out of a garrison of 21,000 Japanese, nearly 20,000 died before the island was declared secured.

Kufuku and Linsoki were among the few Japanese soldiers who didn’t die in the fighting and didn’t commit suicide. They also believing what their government told them about Americans torturing and killing prisoners, so they were too afraid to surrender. The two men felt like they had no choice but to go underground. They also expected that soon the Japanese would be able to take the island back, so they hid during the day in the multitude of tunnels that were all over the island. They came out at night pilfer food and other necessaries from the American garrison’s supply and trash dumps. It was a tough kind of life, but by doing this, Kufuku and Linsoki managed to survive for a long time in a barren and inhospitable island that was mighty short on both vegetation and game. The Americans weren’t interested in exploring Iwo Jima’s hard landscape, a fact that allowed the two Japanese soldiers to go unnoticed for years.

Finally, on January 6th, 1949, two US Air Force corporals in a Jeep spotted a couple of pedestrians in uniforms that looked to be a few sizes too big. The men were walking alongside a road. The soldiers thought the men were Chinese laborers. The men spoke no English and they didn’t seem to want to talk, but the American airmen just assumed they were hitchhiking to the island’s main base and gave them a lift. They dropped them off in front of the garrison’s headquarters building. That probably left Kufuku and Linsoki a little bit unnerved. Nevertheless, they didn’t want to seem suspicious, so they wandered around the American base for hours, at least until a passing American sergeant realized that they were Japanese and took them in. The men were

interrogated, and afterward, they took their captors to their hideout. There, to their amazement, the Americans found a cave richly stocked with canned foods, flashlights, batteries, uniforms, boots, shoes, socks, and other goods that the pair had been pilfering over the years. I’m quite sure they recognized some of the items from the base. While the Japanese soldiers did no real harm, their self-imposed secret mission had come to an end.

interrogated, and afterward, they took their captors to their hideout. There, to their amazement, the Americans found a cave richly stocked with canned foods, flashlights, batteries, uniforms, boots, shoes, socks, and other goods that the pair had been pilfering over the years. I’m quite sure they recognized some of the items from the base. While the Japanese soldiers did no real harm, their self-imposed secret mission had come to an end.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

There are some national events that stay in our thoughts and hearts forever. The Pearl Harbor is one of those events. The attack on Pearl Harbor was so destructive and so unexpected that it shocked everyone…well, most everyone anyway. President Franklin D Roosevelt knew that Japan would likely attack, but thought it would be in the western Pacific Ocean, especially the Philippians. Pearl Harbor was considered an unlikely target. Roosevelt wanted to enter the war, but he wanted to attack Germany, whom he considered to be the bigger threat. In fact, he had ordered the attack on any U-Boats found in the west side of the Atlantic. So, technically the US was already in the war…most people just didn’t know that. Still, the attack on Pearl Harbor was horrific and the United States had to retaliate.

The attack on Pearl Harbor took so many people by surprise. It was a Sunday morning, and many of the military personnel were off base attending church services. The Japanese knew that the ships, planes, and the base in general would be seriously understaffed at the time of the attack. Of course, on the flip side, the fact that so many of the military personnel were away from the base at the time of the attack, meant that the base was able to get back up and running quickly and when we did enter the war, the Japanese were surprised about the attacks coming back at them. Of course, as we all know, the Allies went on to win the war against the Axis nation, including Germany and Japan. It’s been said that people shouldn’t wake the sleeping giant, and that is a wise statement. The Japanese awakened the United States to the fact that appeasing your enemies will not prevent an attack. It takes a show of military might to inform our enemies that it is wise to back away and let the sleeping giants lie.

Of course, the victory that was won following the attack of Pearl Harbor and the US entrance into World War II, came at a high price. A total of 2,403 people (both civilians and soldiers), not to mention ships, airplanes, and

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

other military equipment. After the attack, the people of the United States were…angry!! We quickly geared up and the war was on for the United States. Our delay could never bring back the people we lost, but we would certainly avenge their loss. Today we remember those we lost, and those who went out to take up the fight to protect our country from such a horrendous attack.

It’s not often that a young man “pulls strings” in order to go to war. Most men would rather not go to war, and some will even try to “pull strings” to get out of going. John F Kennedy, who had some health problems, and an old back injury from his college football days, was turned down for the Navy, but his dad managed to pull some strings for his son, who really wanted to go into the navy. Young was desperate, and like most parents, his father wanted to help fulfill that dream. So in 1941, Kennedy’s politically connected father, Joseph Kennedy used his influence to get his sin, John “Jack” into the service. Of course, Joseph might have been thinking ahead to future political maneuvers when he pushed for a military career for his son. Once in the Navy, Kennedy volunteered for PT (motorized torpedo) boat duty in the Pacific in 1942.

It’s not often that a young man “pulls strings” in order to go to war. Most men would rather not go to war, and some will even try to “pull strings” to get out of going. John F Kennedy, who had some health problems, and an old back injury from his college football days, was turned down for the Navy, but his dad managed to pull some strings for his son, who really wanted to go into the navy. Young was desperate, and like most parents, his father wanted to help fulfill that dream. So in 1941, Kennedy’s politically connected father, Joseph Kennedy used his influence to get his sin, John “Jack” into the service. Of course, Joseph might have been thinking ahead to future political maneuvers when he pushed for a military career for his son. Once in the Navy, Kennedy volunteered for PT (motorized torpedo) boat duty in the Pacific in 1942.

“Jack” Kennedy quickly worked to move himself up in rank, and soon he was Lieutenant John F. Kennedy. July 1943 found Lieutenant Kennedy and the crew of PT 109 in combat near the Solomon Islands. People often think that being in the Navy or the Air Force is somehow safer than the Army or Marines, but the reality is that any position in a war

can prove to be dangerous. On August 2, 1943, the middle of the night, Kennedy’s boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer and caught fire. In the ensuing explosion, several of Kennedy’s shipmates were blown overboard into a sea of burning oil. With no regard for his own life, Kennedy dove in to rescue three of the crew and in the process swallowed some of the toxic mixture. Kennedy always blamed his chronic stomach problems on that incident. The ordeal was not quickly over, and for 12 hours, Kennedy and his men clung to the wrecked hull. Finally, he ordered them to abandon ship. Kennedy and the other good swimmers placed the injured on a makeshift raft. They took turns pushing and towing the raft four miles to safety on a nearby island.

can prove to be dangerous. On August 2, 1943, the middle of the night, Kennedy’s boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer and caught fire. In the ensuing explosion, several of Kennedy’s shipmates were blown overboard into a sea of burning oil. With no regard for his own life, Kennedy dove in to rescue three of the crew and in the process swallowed some of the toxic mixture. Kennedy always blamed his chronic stomach problems on that incident. The ordeal was not quickly over, and for 12 hours, Kennedy and his men clung to the wrecked hull. Finally, he ordered them to abandon ship. Kennedy and the other good swimmers placed the injured on a makeshift raft. They took turns pushing and towing the raft four miles to safety on a nearby island.

Their ordeal still wasn’t over. For six days, Kennedy and his crew waited on the island for rescue. There was little to eat on the island, but the men survived by drinking coconut milk and rainwater until native islanders discovered the sailors and offered food and shelter. While they waited, Kennedy tried every night to signal other US Navy ships in the area. In addition, Kennedy scrawled a message on a coconut husk and gestured to the islanders to take it to a nearby PT base at Rendova. Finally, on August 8, a Navy patrol boat picked up the survivors of PT-109.

The men were taken to the hospital to recuperate, and on June 12, 1944, while Kennedy was in the hospital recuperating from back surgery, he received the Navy and Marine Corps medal for “courage, endurance, and

excellent leadership [that] contributed to the saving of several lives and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

excellent leadership [that] contributed to the saving of several lives and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Of course, the rest is history. John F Kennedy went on to become the 35th President of the United States, and on November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. His vice president, Lyndon B Johnson, assumed the presidency upon Kennedy’s death.

Soldiers everywhere have varied backgrounds, but maybe more so during World War I and World War II, as well as wars in which there was a draft. Robert Kerr “Jock” McLaren was a veterinarian by trade, but during his service with the Second Australian Imperial Force, he also became a feared guerrilla fighter who ran missions against the Japanese. I suppose that, while a veterinarian doesn’t work on humans, possessing certain skills would be important in certain situations. McLaren spent countless hours, days, and weeks in the jungles, and after one such assignment, his medical skills suddenly became urgently needed…on himself. McLaren found himself faced with surgery on himself, or certain death. So, in order to save his own life, McLaren set about to remove his own appendix…in the jungle, with a pen knife, two spoons, and coconut fibers.

Soldiers everywhere have varied backgrounds, but maybe more so during World War I and World War II, as well as wars in which there was a draft. Robert Kerr “Jock” McLaren was a veterinarian by trade, but during his service with the Second Australian Imperial Force, he also became a feared guerrilla fighter who ran missions against the Japanese. I suppose that, while a veterinarian doesn’t work on humans, possessing certain skills would be important in certain situations. McLaren spent countless hours, days, and weeks in the jungles, and after one such assignment, his medical skills suddenly became urgently needed…on himself. McLaren found himself faced with surgery on himself, or certain death. So, in order to save his own life, McLaren set about to remove his own appendix…in the jungle, with a pen knife, two spoons, and coconut fibers.

McLaren was just a teenager during World War I, when he served with the 51st (Highland) Division of the British Army. Because he was so young then, it’s unlikely that he saw combat on the Western Front. Nevertheless, his name is found on the rolls from his division’s time in France in 1918. That made people wonder if he participated in fighting during the Spring Offensive. Following the war, McLaren returned to  Scotland and completed training to become a veterinarian. He then moved to Queensland, Australia, where he worked as a veterinary officer in Bundaberg.

Scotland and completed training to become a veterinarian. He then moved to Queensland, Australia, where he worked as a veterinary officer in Bundaberg.

When World War II began, McLaren volunteered for the Second Australian Imperial Force. McLaren, 39 years old at the time, was assigned to the 2/10th Australian Field Workshops, 8th Australian Division and stationed in Singapore. McLaren spent time in a POW camp and escaped along with two other soldiers. After being tortured and faced with a firing squad, the trio were ultimately returned to their cells. McLaren, along with 1,000 British and Australian soldiers, was later transferred to Borneo and held at the Sandakan camp. He made plans to escape again, this time with a Chinese POW named Johnny Funk. The escape took the men to the large Philippine Island of Mindanao, where they joined the resistance led by American Reserve Officer, Lt. Col. Wendell Fertig. He was later given the chance to return to Australia, but chose to remain a guerrilla.

It was during his time as a guerrilla that McLaren’s appendicitis attack occurred. During one patrol as a  guerrilla, McLaren developed a severe case of appendicitis. He knew enough to know that he was going to have to treat himself, or he would die. So, he performed surgery with just a penknife and two spoons. He stitched the incision with coconut fibers. When asked about the act years later, he said, “It was hell, but I came through alright.” A modest remark for such a remarkable act…in the middle of a Philippine jungle in 1944, without any anesthetic and with only the use of a mirror to see. The operation took 4½ hours. Still, as he said he came through it alright, and he would not be that last person to do surgery on themselves. Nevertheless…remarkable.

guerrilla, McLaren developed a severe case of appendicitis. He knew enough to know that he was going to have to treat himself, or he would die. So, he performed surgery with just a penknife and two spoons. He stitched the incision with coconut fibers. When asked about the act years later, he said, “It was hell, but I came through alright.” A modest remark for such a remarkable act…in the middle of a Philippine jungle in 1944, without any anesthetic and with only the use of a mirror to see. The operation took 4½ hours. Still, as he said he came through it alright, and he would not be that last person to do surgery on themselves. Nevertheless…remarkable.

Lieutenant Thomas “Diver” Derrick was one of the 2/48th Battalion of the Australian 9th Infantry division battalion’s most decorated and beloved soldiers, serving in Australia’s most decorated unit in World War II. He was the best of the best, but it was after one event that he actually gained notoriety. Derrick was born on March 20, 1914, at the McBride Maternity Hospital in the Adelaide suburb of Medindie, South Australia, to David Derrick, a laborer from Ireland, and his Australian wife, Ada (née Whitcombe). The Derricks were poor, and Tom often walked barefoot to attend Sturt Street Public School and later Le Fevre Peninsula School. In 1928, aged fourteen, Derrick left school and found work in a bakery. By this time, he had developed a keen interest in sports, particularly cricket, Australian Rules Football, boxing and swimming; his diving in the Port River earned him the nickname of “Diver.”

Lieutenant Thomas “Diver” Derrick was one of the 2/48th Battalion of the Australian 9th Infantry division battalion’s most decorated and beloved soldiers, serving in Australia’s most decorated unit in World War II. He was the best of the best, but it was after one event that he actually gained notoriety. Derrick was born on March 20, 1914, at the McBride Maternity Hospital in the Adelaide suburb of Medindie, South Australia, to David Derrick, a laborer from Ireland, and his Australian wife, Ada (née Whitcombe). The Derricks were poor, and Tom often walked barefoot to attend Sturt Street Public School and later Le Fevre Peninsula School. In 1928, aged fourteen, Derrick left school and found work in a bakery. By this time, he had developed a keen interest in sports, particularly cricket, Australian Rules Football, boxing and swimming; his diving in the Port River earned him the nickname of “Diver.”

Derrick’s notorious accomplishment came during the Battle of Sattelberg in New Guinea in November 1943. His battalion…the 2/48th was participating in the fight. Over a period of two hours, the Australians made several attempts to clamber up the slopes to reach their objective, but each time they were repulsed by intense machine gun fire and grenade attacks. As dusk fell, it appeared impossible to reach the objective or even hold the ground already gained, and the company was ordered the men to retreat. That order brought about an unusual response in Lieutenant Derrick, who was quoted as saying, “Bugger the CO [commanding officer]. Just give me twenty more minutes and we’ll have this place. Tell him I’m pinned down and can’t get out.” With that, then Sergeant Tom Derrick hoisted the Australian Red Ensign at Sattelberg, New Guinea. He moved forward with his platoon, and Derrick attacked a Japanese post  that had been holding up the advance. He quickly destroyed the position with grenades and ordered his second section around to the right flank. The section immediately came under heavy machine gun and grenade fire from six Japanese posts, but that didn’t stop Derrick. Clambering up the cliff face under heavy fire, Derrick held on with one hand while lobbing grenades into the weapon pits with the other. Someone said he was like “a man…shooting for [a] goal at basketball.” Derrick climbed further up the cliff and in full view of the Japanese, he continued to attack the posts with grenades before following up with accurate rifle fire. True to his word, within twenty minutes, he had reached the peak and cleared seven posts…all while the demoralized Japanese defenders fled from their positions to the buildings of Sattelberg. I suppose that if the maneuver had ended differently, Derrick might have been punished for disobeying the order of his commanding officer, but as it was, how could they discipline him for such a one-man-show of prowess.

that had been holding up the advance. He quickly destroyed the position with grenades and ordered his second section around to the right flank. The section immediately came under heavy machine gun and grenade fire from six Japanese posts, but that didn’t stop Derrick. Clambering up the cliff face under heavy fire, Derrick held on with one hand while lobbing grenades into the weapon pits with the other. Someone said he was like “a man…shooting for [a] goal at basketball.” Derrick climbed further up the cliff and in full view of the Japanese, he continued to attack the posts with grenades before following up with accurate rifle fire. True to his word, within twenty minutes, he had reached the peak and cleared seven posts…all while the demoralized Japanese defenders fled from their positions to the buildings of Sattelberg. I suppose that if the maneuver had ended differently, Derrick might have been punished for disobeying the order of his commanding officer, but as it was, how could they discipline him for such a one-man-show of prowess.

Following his successful one-man-attack on the enemy, Derrick returned to his platoon, where he gathered his first and third sections in preparation for an assault on the three remaining machine gun posts in the area. While the platoon was attacking the posts, Derrick personally rushed forward on four separate occasions and threw his grenades at a range of about 8 yards, before all three were silenced. Derrick’s platoon held their position that night, before the 2/48th Battalion moved in to take Sattelberg unopposed the following morning. I’m sure that brought a level of shock to the commanding officer, who had expected a much different outcome and a much different enemy the next morning. The, then proud, battalion commander insisted that Derrick personally hoist the Australian flag over the town. It was raised at 10:00am on November 25, 1943.

The final assault on Sattelberg was later dubbed “Derrick’s Show” within the 2/48th Battalion. Derrick was already a celebrity within the 9th Division, but this action brought him to wide public attention. I suppose that could have been seen as just Derrick’s irritation over the retreat, but it also could have and was taken as disobeying an order. Derrick had advanced on multiple Japanese machine gun positions, uphill through the jungle, while under covering fire from his squadmates…and he did it by himself. In all, he cleared out 10 enemy positions, helping his unit accomplish their objective and receiving the Victoria Cross for his efforts. Unfortunately, Derrick was killed late in World War II, suffering grievous injuries at the Battle of Tarakan in May 1945.

The final assault on Sattelberg was later dubbed “Derrick’s Show” within the 2/48th Battalion. Derrick was already a celebrity within the 9th Division, but this action brought him to wide public attention. I suppose that could have been seen as just Derrick’s irritation over the retreat, but it also could have and was taken as disobeying an order. Derrick had advanced on multiple Japanese machine gun positions, uphill through the jungle, while under covering fire from his squadmates…and he did it by himself. In all, he cleared out 10 enemy positions, helping his unit accomplish their objective and receiving the Victoria Cross for his efforts. Unfortunately, Derrick was killed late in World War II, suffering grievous injuries at the Battle of Tarakan in May 1945.

Amazingly, the islands of the world have held an importance during wartime, that most of us would never have dreamed. These seemingly insignificant places proved to be great staging places time and again, and so became places that were fought over viciously. The Solomon Islands were among those places fought over during World War II…most specifically Guadalcanal. The island of Guadalcanal is the largest of the Solomons Islands, which is in the South Pacific Ocean, located northeast of Australia. The Solomon Islands are a group of 992 islands and atolls, 347 of which are inhabited. The Solomons have 87 Indigenous languages. They were first discovered in 1568 by Spanish navigator Alvaro de Mendana de Neyra (1541-95). By 1893, the British had annexed Guadalcanal, along with the other central and southern Solomons, which made sense, since they also owned Australia. In 1885, the Germans took control of the northern Solomons, but transferred these islands, except for Bougainville and Buka (which eventually went to the Australians) to the British in 1900. So, the Solomon Islands have been transferred around some over the centuries, as most countries have been, a time or two anyway.

Amazingly, the islands of the world have held an importance during wartime, that most of us would never have dreamed. These seemingly insignificant places proved to be great staging places time and again, and so became places that were fought over viciously. The Solomon Islands were among those places fought over during World War II…most specifically Guadalcanal. The island of Guadalcanal is the largest of the Solomons Islands, which is in the South Pacific Ocean, located northeast of Australia. The Solomon Islands are a group of 992 islands and atolls, 347 of which are inhabited. The Solomons have 87 Indigenous languages. They were first discovered in 1568 by Spanish navigator Alvaro de Mendana de Neyra (1541-95). By 1893, the British had annexed Guadalcanal, along with the other central and southern Solomons, which made sense, since they also owned Australia. In 1885, the Germans took control of the northern Solomons, but transferred these islands, except for Bougainville and Buka (which eventually went to the Australians) to the British in 1900. So, the Solomon Islands have been transferred around some over the centuries, as most countries have been, a time or two anyway.

During World War II, Guadalcanal became a hard-fought-over island, with the Japanese in control in early 1943. Then, on February 8, 1943, Japanese troops evacuate Guadalcanal, leaving the island in Allied possession after a prolonged campaign. When Japan lost Guadalcanal, it paved the way for other Allied wins in the Solomon Islands.

The Japanese had invaded the Solomon Islands in 1942 during World War II and immediately began building a strategic airfield on Guadalcanal. On August 7, 1942, US Marines landed on the island, signaling the Allies’ first major offensive against Japanese-held positions in the Pacific. The Japanese response to the US Marines “boots on the ground” was to quickly launch sea and air attacks. The battles that followed were bloody and made even more miserable in the debilitating tropical heat. Nevertheless, the Marines fought hard with Japanese troops on land, and in the waters surrounding Guadalcanal, the US Navy fought six major engagements with the Japanese between August 24 and November 30. In mid-November 1942, the five Sullivan brothers from Waterloo, Iowa, died together when the Japanese sank their ship, the USS Juneau. These days they try not to put brother together in battle, but the Sullivan brothers had requested it, and so it was granted.

Both the United States and the Japanese suffered heavy losses of men, warships, and planes in the battle for Guadalcanal. It is estimated 1,600 US troops were killed and over 4,000 were wounded. Several thousand more died from disease. The Japanese lost 24,000 soldiers. Finally, on December 31, 1942, Emperor Hirohito told his troops they could withdraw from the area. About five weeks later, the Americans secured Guadalcanal. American authorities declared Guadalcanal secure on February 9, 1943. After the war, American and Japanese groups have repeatedly visited Guadalcanal to search for remains of missing soldiers. Some 7,000 Japanese remain missing on the island, and islanders still bring the Japanese groups bones that the islanders say are those of unearthed Japanese soldiers.

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

The envoys’ message was simple: “The British garrison there should simply surrender to the Japanese—resistance was futile.” The envoys were sent home with the following retort: “The governor and commander in chief of Hong Kong declines absolutely to enter into negotiations for the surrender of Hong Kong…”

The unsuccessful negotiations brought a swift wave of Japanese troops, who in retaliation for the refused surrender, landed in Hong Kong with artillery fire for cover and the following order from their commander: “Take no prisoners.” The troops quickly overran a volunteer antiaircraft battery, and the Japanese invaders roped together the captured soldiers. In a complete disregard for human life, a complete disregard for the Geneva Convention rules, or any rules of common decency, the Japanese proceeded to bayonet them to death. Even those who offered no  resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

On that same day, the War Powers Act was passed by Congress, authorizing the president to initiate and terminate defense contracts, reconfigure government agencies for wartime priorities, and regulate the freezing of foreign assets. It also permitted him to censor all communications coming in and leaving the country. President Franklin D Roosevelt appointed the executive news director of the Associated Press, Byron Price, as director of censorship. Although invested with the awesome power to restrict and withhold news, Price took no extreme measures, allowing news outlets and radio stations to self-censor, which they did. Most top-secret information, including the construction of the atom  bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

“The most extreme use of the censorship law seems to have been the restriction of the free flow of “girlie” magazines to servicemen…including Esquire, which the Post Office considered obscene for its occasional saucy cartoons and pinups. Esquire took the Post Office to court, and after three years the Supreme Court ultimately sided with the magazine.” It amazes me just how much times have changed. These days the “girlie” trash is totally acceptable, but truth is censored and lies are allowed. Too bad we are so far out from those days.

Thermopolis, Wyoming…a favorite destination for my husband and me. We take a trip there every year for our anniversary. I suppose that for many people, Thermopolis would seem too quiet, too small, and too little to do, but for us it is just perfect. With its hot springs and river walk trail, it is just perfect for us, and the hot spring ponds filled with goldfish of a size you simply cannot imagine until you see them. I’ve been told that they came from people getting rid of the small goldfish, and the warm water, along with the pond size, allowed the smaller goldfish to grow quite large. Thermopolis also had a dinosaur museum, although we have never been there. We go to the area for the hot tub and the trail for sure.

Thermopolis, Wyoming…a favorite destination for my husband and me. We take a trip there every year for our anniversary. I suppose that for many people, Thermopolis would seem too quiet, too small, and too little to do, but for us it is just perfect. With its hot springs and river walk trail, it is just perfect for us, and the hot spring ponds filled with goldfish of a size you simply cannot imagine until you see them. I’ve been told that they came from people getting rid of the small goldfish, and the warm water, along with the pond size, allowed the smaller goldfish to grow quite large. Thermopolis also had a dinosaur museum, although we have never been there. We go to the area for the hot tub and the trail for sure.

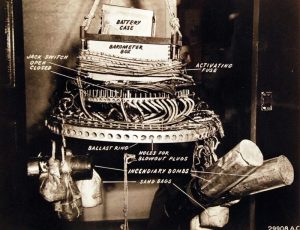

While Thermopolis might seem like the safest little out of the way place, there was a time when it was actually a target for an attack. During World War II, the Japanese set their sights on Wyoming. It makes little sense to me, but it was the target they chose. During World War II, the Japanese were experimenting with a new kind of bomb. It really wasn’t the greatest idea, but they did send some of them out. The problem with balloons is that it’s difficult to control where it is going…especially when it is unmanned. It’s hard to say what the exact target was, but on December 5, 1944, coal miners outside of Thermopolis heard something from the skies above and saw an explosion streak across the dark sky. When the object landed, it was discovered to be a Japanese Fu-Go Balloon Bomb. Though the Japanese launched 9,300 of these bombs, only about 300 made it to land, and the Thermopolis bomb was the first one to reach the United States.

I find it hard to believe that the first Fu-Go Balloon Bomb made it all the way to Wyoming before exploding, when the only Fu-Go Balloon Bomb to actually kill anyone was one that landed near Bly, Oregon on May 5, 1945, that killed a pregnant woman and five children after they approached the unexploded balloon that had landed nearby. The balloon exploded as they investigated it. After that, the public was warned to stay away from the objects, but the news stories were still scarce. In fact, the Japanese only ever learned of the landing in Wyoming!! I have no idea how the media held themselves back.

Landing so many balloons in America was an impressive feat because the inter-continental attack was considered impossible at the time. Whatever the Japanese had hoped to gain by this relatively ineffective “bomb” is unknown, but it was a real failure. My guess is that most of them exploded over the ocean, doing no damage. Nevertheless, these massive balloons were a bit of a marvel…so to speak. They had to carry more than 1,000 pounds across the ocean, which was no easy task, especially for technology at the time. The fact that any of them made it here was impressive, I suppose. They were impressive balloons from a technologic standpoint. They were controlled by altimeters that kept the balloon in the newly discovered jet stream until it was over America, where it would fall to the ground and detonate…or so was the plan. The goal of the mission was to cause panic and fear in the United States, but a media blackout meant that these landings and  explosions went unreported. A blackout was the only way.

explosions went unreported. A blackout was the only way.

These attacks were actually quite amazing, because they were the longest ranged assaults in the history of warfare. It wasn’t until 1982 (during the Falkland Islands War) that the distance was topped. Today, the story of the Fu-Go Balloon Bombing is rarely told in Wyoming outside of Thermopolis, where it has supposedly become local folklore. Strange that I have never heard of it, even with the many years we have been spending our anniversary there. I will most definitely have to ask about it the next time we go.

It’s hard to picture a dentist as being a hero, but US Army Medic Ben Salomon, who was a dentist before he was drafted in to the US Army as a private in 1940, as World War II was in its early stages. Salomon was assigned, not to the medical units, but rather, to the infantry. It was in the infantry during rifle and pistol qualifications that Salomon was rated an Expert Marksman. He also had medical knowledge that could be used during battlefield surgery. Salomon was assigned to a unit as their medic. Being a medic in wartime means that you are doing the noble thing, a task which is not often recognized as anything special. I think was have all seen the television show, MASH, in which the position of Army Doctor is viewed as mostly safe, far from the front lines, and given to a little bit of hanky panky. It doesn’t often paint a picture of heroic actions, although, sometimes the doctors are heroic (Nevertheless, I don’t mean to say that all military doctors are like the doctors on MASH, who are, after all, playing a part.) Medics serve and protect like every other serviceman, but they sometimes see a lot more of war’s ugly side. These unit medics might saw torn apart friends, horrific injuries, and a lot of deaths. The men they served with every day were their friends, and while the medic was usually behind the unit in a tent, caring for the wounded, these were not strangers to them. They were friends and comrades in arms.

It’s hard to picture a dentist as being a hero, but US Army Medic Ben Salomon, who was a dentist before he was drafted in to the US Army as a private in 1940, as World War II was in its early stages. Salomon was assigned, not to the medical units, but rather, to the infantry. It was in the infantry during rifle and pistol qualifications that Salomon was rated an Expert Marksman. He also had medical knowledge that could be used during battlefield surgery. Salomon was assigned to a unit as their medic. Being a medic in wartime means that you are doing the noble thing, a task which is not often recognized as anything special. I think was have all seen the television show, MASH, in which the position of Army Doctor is viewed as mostly safe, far from the front lines, and given to a little bit of hanky panky. It doesn’t often paint a picture of heroic actions, although, sometimes the doctors are heroic (Nevertheless, I don’t mean to say that all military doctors are like the doctors on MASH, who are, after all, playing a part.) Medics serve and protect like every other serviceman, but they sometimes see a lot more of war’s ugly side. These unit medics might saw torn apart friends, horrific injuries, and a lot of deaths. The men they served with every day were their friends, and while the medic was usually behind the unit in a tent, caring for the wounded, these were not strangers to them. They were friends and comrades in arms.

Just one month after Salomon’s promotion to captain, he experienced his first battle. Salomon volunteered to replace the 2nd Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment’s field surgeon, who had been wounded. The unit was sent to Saipan to fight the Japanese forces. Little did Salomon know that this would be his only battle. When the unit landed in Saipan, they found immediately themselves in one of the most intense fights in the Pacific arena. Apparently this little island had been determined to be vital…no matter which side you were on. The Japanese army was not willing to concede the island and the US Army was adamant that they needed to take it. By the time Salomon’s unit arrived, the Japanese had taken the approach of advance and attack to their own deaths.

The tents for the field surgeons were located 50 yards behind the front, and it was there that Salomon worked to triage the severely wounded men. On July 6, 1944, the Japanese reached the trenches and Salomon’s position. Then on July 7th, the Japanese made it over the trenches and went straight to the medical tents. Inside, Salomon was treating wounded soldiers. He looked up and saw a Japanese soldier storm into the tent and bayonet one of the wounded and unarmed soldiers. Solomon acted instinctively. He grabbed an M1 rifle which was on a table close by and fired, killing the enemy soldier. For a medic, who never expected to need to fire his weapon, that situation must have come as a bit of a shock, but that soldier was not to be the only one Salomon killed that day. He turned back to the wounded soldiers, and then he saw two more enemy soldiers burst into the tent. There wasn’t much room in the tents, and they weren’t designed for hand to hand combat, but the tent soon became the battlefield, nevertheless. Salomon began swinging the rifle and clubbed the first soldier, then jamming the second with the butt of the weapon. Then, he shot one and bayoneted the other.

Immediately, four more Japanese soldiers made their way into the medical tent and tried to catch Salomon by surprise. One of the soldiers had a knife that Salomon kicked out of his hand before firing his rifle, killing one soldier and using his bayonet to kill another. By now, Salomon was out of bullets, so he picked up the knife and engaged with the two remaining enemy fighters. He killed one using the knife before head-butting the other, who was then shot by one of the patients in the tent. After dispatching the enemy soldiers, Salomon ordered his colleagues to evacuate the wounded. He would stay behind to hold off the enemy to give them the extra time they needed. As Captain Salomon loaded his rifle, the 30 wounded soldiers and orderlies in the tent started to retreat. The decision to stay and fight while the wounded were evacuated saved many lives, but Salomon was now in a battle that he had no hope of winning, much less living through. Ben Salomon made his last stand. He commandeered a heavy machine gun and was last seen firing at oncoming Japanese troops.

When the American troops were finally able to return to the area, they found Salomon’s body slumped over the machine gun, surrounded by the bodies of 98 Japanese soldiers. He had been shot 76 times and had 24  bayonet wounds on his body. Yes, Captain Salomon had died in the battle, but not before he killed 98 enemy soldiers, and the wounded soldiers and the medics with him had all managed to escape. Salomon was a serious force to be reckoned with, as the Japanese found out that day.

bayonet wounds on his body. Yes, Captain Salomon had died in the battle, but not before he killed 98 enemy soldiers, and the wounded soldiers and the medics with him had all managed to escape. Salomon was a serious force to be reckoned with, as the Japanese found out that day.

Medical personnel were considered ineligible for the Medal of Honor at that time, due to the terms of the Geneva Convention, so the request that he be awarded the medal was denied. After numerous other attempts over the years, Salomon’s bravery was finally recognized with the Medal of Honor in 2002, 58 years after his death.

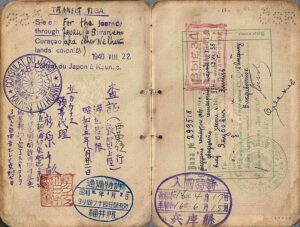

When we thing of people who were heroes for the Jewish people during World War II, we seldom think of true enemies of the Allied Nations. Still, there are people in all nations, no matter how evil the nation, who are good. One such man was Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat who served as vice-consul for the Japanese Empire in Kaunas, Lithuania. Sugihara was born on January 1, 1900 in Mino, Gifu prefecture, to a middle-class father, Yoshimi Sugihara and an upper-middle class mother, Yatsu Sugihara.

When we thing of people who were heroes for the Jewish people during World War II, we seldom think of true enemies of the Allied Nations. Still, there are people in all nations, no matter how evil the nation, who are good. One such man was Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat who served as vice-consul for the Japanese Empire in Kaunas, Lithuania. Sugihara was born on January 1, 1900 in Mino, Gifu prefecture, to a middle-class father, Yoshimi Sugihara and an upper-middle class mother, Yatsu Sugihara.

Sugihara became the vice-consul in 1939. His duties included reporting on Soviet and German troop movements, and to find out if Germany planned an attack on the Soviets and, if so, to report the details of this attack to his superiors in Berlin and Tokyo. As vice-consul, I’m sure he never expected to go against the orders of his superiors. I’m sure that he thought, as most of us do, that our country is the best one, and that our government is honorable and basically good…until we don’t. During the second world war, Sugihara made the decision…against orders from superiors…to help 6,000 Jews escape Europe by issuing transit visas to them, so that they could travel through Japanese territory. By doing this, he was risking his job and the lives of his family, but he knew that the things that were happening to the Jews were wrong, and he could not stand by and be a party to their deaths. The Jews that Sugihara helped were refugees from German-occupied Western Poland and Soviet-occupied Eastern Poland, as well as residents of Lithuania. I’m sure that Sugihara’s superiors didn’t want to anger their ally, Adolf Hitler, so they had told Sugihara to turn a blind eye to the fate of the Jewish people, and let the Nazis do what they wanted to do to them. But, Sugihara had a conscience, and he could not allow he Jews to be murdered in such a horrific fashion. He had to help as many as he could.

From July 18 to August 28, 1940, Sugihara being aware that Jewish visa applicants were in danger if they  stayed behind, Sugihara decided to ignore his orders and issued ten-day visas to Jews for transit through Japan. Given his inferior post and the culture of the Japanese Foreign Service bureaucracy, this was an unusual act of disobedience. Sugihara spoke to Soviet officials who agreed to let the Jews travel through the country via the Trans-Siberian Railway…at five times the standard ticket price, of course. I guess there is no price too high…seriously. Sugihara continued to spend 18 to 20 hours a day writing hand-write visas, reportedly producing a normal month’s worth of visas each day, until September 4th, when he had to leave his post before the consulate was closed. While his time was cut short at that consulate, he had granted thousands of visas to Jews, many of whom were heads of households, thus permitting them to take their families with them. It is said that before he left, he handed the official consulate stamp to a refugee so that more visas could be forged, but his son, Nobuki Sugihara, insists that his father never gave the stamp to anyone. According to witnesses, he was still writing visas while in transit from his hotel and after boarding the train at the Kaunas Railway Station, throwing visas into the crowd of desperate refugees out of the train’s window even as the train pulled out. It was an insanely brave act, and it did not go unnoticed.

stayed behind, Sugihara decided to ignore his orders and issued ten-day visas to Jews for transit through Japan. Given his inferior post and the culture of the Japanese Foreign Service bureaucracy, this was an unusual act of disobedience. Sugihara spoke to Soviet officials who agreed to let the Jews travel through the country via the Trans-Siberian Railway…at five times the standard ticket price, of course. I guess there is no price too high…seriously. Sugihara continued to spend 18 to 20 hours a day writing hand-write visas, reportedly producing a normal month’s worth of visas each day, until September 4th, when he had to leave his post before the consulate was closed. While his time was cut short at that consulate, he had granted thousands of visas to Jews, many of whom were heads of households, thus permitting them to take their families with them. It is said that before he left, he handed the official consulate stamp to a refugee so that more visas could be forged, but his son, Nobuki Sugihara, insists that his father never gave the stamp to anyone. According to witnesses, he was still writing visas while in transit from his hotel and after boarding the train at the Kaunas Railway Station, throwing visas into the crowd of desperate refugees out of the train’s window even as the train pulled out. It was an insanely brave act, and it did not go unnoticed.

In 1985, the State of Israel honored Sugihara as one of the Righteous Among the Nations for his actions…the highest honor given to non-Jews.. He is the only Japanese national ever to receive it. The year 2020 was “The Year of Chiune Sugihara” in Lithuania. It has been estimated as many as 100,000 people alive today are the descendants of the recipients of Sugihara visas. When asked by Moshe Zupnik why he risked his career to save other people, he said simply, “I do it just because I have pity on the people. They want to get out so I let them  have the visas.”

have the visas.”

Chiune Sugihara died at a hospital in Kamakura, on July 31, 1986. Despite the publicity given him in Israel and other nations, Sugihara remained virtually unknown in his home country. I’m sure they didn’t consider him anything more than a criminal. Only when a large Jewish delegation from around the world, including the Israeli ambassador to Japan, attended his funeral, did his neighbors find out what he had done. His subsequent considerable posthumous acclaim contrasts with the obscurity in which he lived following the loss of his diplomatic career.