Ireland

Margaret Haughery was a philanthropist in the New Orleans area. A philanthropist is “a person who seeks to promote the welfare of others, especially by the generous donation of money to good causes.” She was well known as “the mother of the orphans.” Margaret Gaffney Haughery was such a kind and loving person, and in 1880s New Orleans, she was beyond loved. She was so loved that she was known as “Our Margaret,” “The Bread Woman of New Orleans” and “Mother of Orphans.” The reason, Haughery is so loved is that she devoted her life’s work to the care and feeding of the poor and hungry, and to fund and build orphanages throughout the city.

Margaret Haughery was a philanthropist in the New Orleans area. A philanthropist is “a person who seeks to promote the welfare of others, especially by the generous donation of money to good causes.” She was well known as “the mother of the orphans.” Margaret Gaffney Haughery was such a kind and loving person, and in 1880s New Orleans, she was beyond loved. She was so loved that she was known as “Our Margaret,” “The Bread Woman of New Orleans” and “Mother of Orphans.” The reason, Haughery is so loved is that she devoted her life’s work to the care and feeding of the poor and hungry, and to fund and build orphanages throughout the city.

Haughery was an Irish immigrant, and she was also a widow. Haughery held many titles. She was commonly referred to as the “Angel of the Delta,” “Mother Margaret,” “Margaret of New Orleans,” the “Celebrated Margaret,” “Head Mame,” and “Margaret of Tully.” A Catholic, she worked closely with New Orleans Sisters of Charity, associated with the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans. Her work was mainly with poor and orphaned widows and kids. She opened four orphanages in the New Orleans area in the 19th century. She didn’t stop there, however. Many years later in the 20th and 21st centuries, several of the asylums Margaret founded as places of shelter for orphans and widows evolved into homes for the elderly.

After her many long years of working with the needy, Haughery, a woman known for her great work in charity, became famed for her lifelong championing of the destitute. Some people considered her a living saint worthy of canonization. Haughery didn’t have a wealthy start. On the contrary, she was born into poverty and orphaned at a young age. She struggled most of her young life. She then began her adult life as a washwoman and a peddler. Nevertheless, she died a businesswoman and philanthropist and received a state funeral. Her life proves what is said in Luke 6:38 in the Bible, “Give, and it will be given to you. Good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap. For with the measure you use it will be measured back to you.” Haughery was an extravagant giver. It doesn’t mean that she gave tons of money, although over the years, she did. Nevertheless, she gave as much as she could, sometimes even more.

Margaret was born in a stone cottage in Ireland in 1813, the fifth child of William and Margaret O’Rourke Gaffney. The family fell on hard times and the family divided, leaving the three younger children in Ireland with William’s brother. Before long the rest of her family died or, as in the case of her brother, ran off. Haughery was alone and homeless. A Mrs. Richards, who had made the overseas crossing with the Gaffney family heard of Margaret’s plight. She had lost her husband to yellow fever. She took Margaret into her home. There Margaret remained for some years, where she worked for her keep. In fact, she may have been little more than a servant. Margaret received no formal education, and never learned to read or write. When old enough, Margaret went into domestic service, which was common for Irishwomen in Baltimore at that time. While she basically started out with nothing, she received the “kindness” of Mrs Richards and then turned her life around. Margaret went on to show kindness to so many others, and in the end, she became one of the most beloved women in New Orleans.

Margaret married Irish-born Charles Haughery on October 10, 1835, when she was 21 years old. Margaret persuaded him that a change in climate might be therapeutic for his poor health. So, they moved south. They left Baltimore on the ship Hyperion and reached New Orleans on November 20, 1835. Unfortunately, New Orleans was in the middle of yellow fever and cholera epidemics. For a time, Charles’ health showed a slight improvement, but it was short-lived and medical advice recommended a sea journey. In desperation, Charles decided to go to Ireland, which was his native land. The trip had to be delayed for several months pending the birth of the couple’s first child, a girl named Frances. Eventually, Charles made the voyage but after some months Margaret received word that he died shortly after reaching his destination. A short time later, Frances became seriously ill and died. Once again, Margaret’s family was wiped out, and she was just 23 years old. At this point, Margaret Haughery could have given up in despair, but she didn’t. She turned her life around and became one of the most beloved women in New Orleans.

In her will Margaret left everything to charities, without distinction of religion, for widows, orphans, and the  elderly. She left all her wealth to charities with the exception of the bakery, which she bequeathed to her foster son, Bernard Klotz. According to her will, the rest of her wealth. When Margaret died and her will was read, with all her giving, she had still saved a great deal of money. She somehow had given so much, and still had more to give. She left every cent of it to the different orphan asylums of the city. Each orphanage was given something, whether they were for white children or black, for Jews, Catholics, or Protestants, made no difference. Margaret always said, “They are all orphans alike.” Margaret signed her will with a cross instead of a name as she never learned to read or write. Her signature, a reminder of her humble beginnings, great business successes, and mark on humanity, despite being unable to read or write.

elderly. She left all her wealth to charities with the exception of the bakery, which she bequeathed to her foster son, Bernard Klotz. According to her will, the rest of her wealth. When Margaret died and her will was read, with all her giving, she had still saved a great deal of money. She somehow had given so much, and still had more to give. She left every cent of it to the different orphan asylums of the city. Each orphanage was given something, whether they were for white children or black, for Jews, Catholics, or Protestants, made no difference. Margaret always said, “They are all orphans alike.” Margaret signed her will with a cross instead of a name as she never learned to read or write. Her signature, a reminder of her humble beginnings, great business successes, and mark on humanity, despite being unable to read or write.

Like the United States, Ireland wanted to be free from the rule of the Britain…to become a sovereign nation. Also, like the United States, the British did not want to release Ireland. So began The Irish War of Independence also known as the Anglo-Irish War. The war was fought guerrilla warfare style in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces, which included the British Army, along with the quasi-military Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and its paramilitary forces the Auxiliaries and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC).

Like the United States, Ireland wanted to be free from the rule of the Britain…to become a sovereign nation. Also, like the United States, the British did not want to release Ireland. So began The Irish War of Independence also known as the Anglo-Irish War. The war was fought guerrilla warfare style in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces, which included the British Army, along with the quasi-military Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and its paramilitary forces the Auxiliaries and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC).

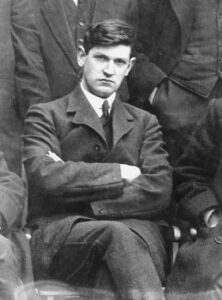

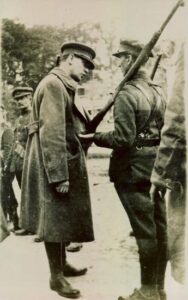

It was in the early part of the century, that a man names Michael Collins joined Sinn Fein, which was an Irish political party dedicated to achieving independence for all Ireland. The Sinn Fein party became the unofficial political wing of militant Irish groups in their struggle to throw off British rule from its inception. The idea of giving Ireland “Home Rule” was not a new one. It was first introduced in 1911, when the British Liberal government approved negotiations for Irish Home Rule, but the Conservative Party opposition in Parliament, combined with Ireland’s anti-Home Rule factions, defeated the plans. Then, with the outbreak of World War I, the British government tabled further discussion of Irish self-determination. It was then that Collins and other Irish nationalists responded by staging the Easter Rising of 1916.

In 1918, with the threat of conscription (conscription is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service) being imposed on the island, the Irish people gave Sinn Fein a majority in national elections, and the party established an independent Irish parliament, Dail Eireann, which declared Ireland a sovereign republic. This was, of course, in direct rebellion against British rule. Collins led the Irish Volunteers, a prototype of the Irish Republican Army, in a widespread and effective guerrilla campaign against British forces in 1919. The war went on for another two years before a cease-fire was finally declared. Collins

stepped up a one of the architects of the historic 1921 peace treaty with Great Britain, which finally granted autonomy to southern Ireland. Their work had finally paid off.

stepped up a one of the architects of the historic 1921 peace treaty with Great Britain, which finally granted autonomy to southern Ireland. Their work had finally paid off.

It seemed that maybe, finally all was finally right in Southern Ireland, and in January 1922, Sinn Fein founder Arthur Griffith was elected president of the newly established Irish Free State. Griffith appointed Collins to be his finance minister. Collins held the post until he was assassinated by Republican extremists in an ambush in west County Cork, Ireland on August 22, 1922. He was laid to rest in Dublin.

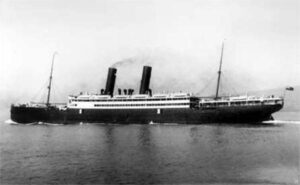

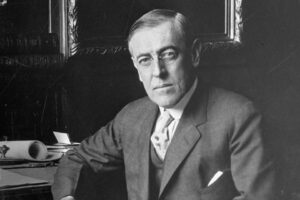

The SS California, owned by Anchor Line Steamship Company; a Scottish merchant shipping company that was founded in 1855 and dissolved in 1980; departed New York on January 29, 1917, bound for Glasgow, Scotland, with 205 passengers and crewmembers on board. While the trip should have been a pleasant journey, world events would soon happen that would change everything in an instant. On February 3, 1917, United States President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech in which he “broke diplomatic relations with Germany and warned that war would follow if American interests at sea were again assaulted.” Of course, all ship sailing the seas, especially those departing or arriving in the United States, or any that had US passengers were warned about the possibility of a German attack.

The SS California, owned by Anchor Line Steamship Company; a Scottish merchant shipping company that was founded in 1855 and dissolved in 1980; departed New York on January 29, 1917, bound for Glasgow, Scotland, with 205 passengers and crewmembers on board. While the trip should have been a pleasant journey, world events would soon happen that would change everything in an instant. On February 3, 1917, United States President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech in which he “broke diplomatic relations with Germany and warned that war would follow if American interests at sea were again assaulted.” Of course, all ship sailing the seas, especially those departing or arriving in the United States, or any that had US passengers were warned about the possibility of a German attack.

February 7, 1917, found the SS California some 38 miles off the coast of Fastnet, Ireland, when the ship’s captain, John Henderson, spotted a submarine off his ship’s port side at a little after 9am. I can only imagine the sinking feeling the captain must have felt at that moment. The Germans were not known for any kind of compassion, and they didn’t particularly care if this was a passenger ship. They figured that the ship might be carrying weapons, and they actually might have been. Captain Henderson ordered the gunner at the stern of the ship to fire in defense, if necessary. Unfortunately, there would not be time to do so, because moments later and without warning, the submarine fired two torpedoes at the ship. The first torpedo missed, but the second torpedo exploded into the port side of the steamer, killing five people instantly. The explosion of that torpedo was so violent and devastating that it caused the 470-foot, 9,000-ton steamer to sink just nine minutes later. The crew quickly sent desperate S.O.S. calls, but the best they could hope for was a hasty arrival of rescue ships. Time was simply not on their side, as 38 people drowned after the initial explosion, and with the initial 5 who died when the torpedo impacted the ship, a total of 43 died. It was an act of war by the Germans.

The Germans were known for this type of blatant attack, in complete defiance of Wilson’s warnings. It’s almost as if they were simply crazed with hatred. Because of Wilson’s warnings about the consequences of unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent discovery and release of the Zimmermann telegram, the Germans reached out to the foreign minister to the Mexican government involving a possible Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between Germany and the United States. That caused Wilson and the United States to take the final steps towards war. On April 2, 1917, Wilson delivered his war message before Congress. It was this action that brought about the United States’ entrance into the First World War, which came about just four days later.

The Germans were known for this type of blatant attack, in complete defiance of Wilson’s warnings. It’s almost as if they were simply crazed with hatred. Because of Wilson’s warnings about the consequences of unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent discovery and release of the Zimmermann telegram, the Germans reached out to the foreign minister to the Mexican government involving a possible Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between Germany and the United States. That caused Wilson and the United States to take the final steps towards war. On April 2, 1917, Wilson delivered his war message before Congress. It was this action that brought about the United States’ entrance into the First World War, which came about just four days later.

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The ship had, in addition to its crew, a number of civilian mail workers. The exact number of dead is unknown, but researchers from the National Maritime Museum believe it was at least 564. The ship’s log, however, states that she carried 77 crew and 694 passengers on her final voyage. This number would seem more correct to me simply because of the records normally kept in logbooks. There is someone assigned to keep that log, and while they could have done a poor job, it is more unlikely that just trusting the number to a random guess of a historian who came along later. The sinking wasn’t the first attack that had been waged on RMS Leister. She had been previously attacked in the Irish Sea, but the torpedoes missed their target. On October 10, 1918, the manifest included more than 100 British civilians, 22 postal sorters (working in the mail room) and almost 500  military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

Just before 10am, as RMS Leister was sailing east of the Kish Bank in a heavy swell, some of the passengers saw a torpedo approach from the port side and pass in front of the bow. I’m sure a panic ensued, and then a second torpedo followed shortly afterwards. This torpedo struck the ship forward on the port side in the vicinity of the mail room. The ship attempted evasive action, trying to make a U-turn in an attempt to return to Kingstown, but the damage was done. As it began to settle slowly by the bow, RMS Leister sank rapidly, helped along by a third torpedo strike, which caused a huge explosion. Whether the number of victims listed is right or wrong, doesn’t really matter, because either number would make the sinking of RMS Leister, the largest single loss of life in the Irish Sea.

Despite the heavy seas, the crew managed to launch several lifeboats and some passengers clung to life-rafts. The survivors were rescued by HMS Lively, HMS Mallard, and HMS Seal. Among the civilian passengers lost in the sinking were socially prominent people such as Lady Phyllis Hamilton, daughter of the Duke of Abercorn, Robert Jocelyn Alexander, son of Irish composer Cecil Frances Alexander, Reverand John Bartley, the Presbyterian minister of Tralee who was travelling to visit his mortally wounded son in hospital, Thomas Foley and his wife Charlotte Foley (née Barrett) who was the brother-in-law of the world-famous Irish tenor John McCormack who adopted their eldest son, and Richard Moore, only son of British architect Temple Moore. The first member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service to die on active duty, Josephine Carr, was among those who died, as were two prominent officials of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, James McCarron and Patrick Lynch. Several of the military personnel who died are buried in Grangegorman Military Cemetery.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.

Today is Saint Patrick’s Day, but I don’t believe in Luck. I believe in blessed. Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations are all about “the luck” of the Irish. I’m not real sure where that idea got started, and I know that it’s all in fun, but luck isn’t real, and blessing is. Saint Patrick was born in Britain, but he was kidnapped by Irish pirates at 16 and enslaved for six years. They took him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in the Confession that “the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development.” Often it is when we are our lowest time, that we finally look up and find the Lord. He explains that “the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven his sins and convert to Christianity.” While Saint Patrick was held in captivity, he was assigned to work as a shepherd, but while there, he also strengthened his relationship with God through prayer, eventually leading him to convert to Christianity.

Today is Saint Patrick’s Day, but I don’t believe in Luck. I believe in blessed. Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations are all about “the luck” of the Irish. I’m not real sure where that idea got started, and I know that it’s all in fun, but luck isn’t real, and blessing is. Saint Patrick was born in Britain, but he was kidnapped by Irish pirates at 16 and enslaved for six years. They took him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in the Confession that “the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development.” Often it is when we are our lowest time, that we finally look up and find the Lord. He explains that “the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven his sins and convert to Christianity.” While Saint Patrick was held in captivity, he was assigned to work as a shepherd, but while there, he also strengthened his relationship with God through prayer, eventually leading him to convert to Christianity.

After six years of captivity, Patrick heard a voice telling him in a dream that he would soon go home, and then that his ship was ready. There was no “luck” to it. God spoke to him in a dream, and he obeyed. He was blessed with his freedom. He immediately took action, and escaping from his master, he  travelled to a port, two hundred miles away. Once there, Patrick found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days of sailing, they landed, presumably in Britain. Odd that they didn’t seem to know. All the passengers and crew left the ship, walking for 28 days in a “wilderness” and almost starving to death. After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar, and since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his reputation as a man of God grew. By the time Patrick arrived back to his family, he was a young man of twenty years. Patrick continued to study Christianity.

travelled to a port, two hundred miles away. Once there, Patrick found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days of sailing, they landed, presumably in Britain. Odd that they didn’t seem to know. All the passengers and crew left the ship, walking for 28 days in a “wilderness” and almost starving to death. After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar, and since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his reputation as a man of God grew. By the time Patrick arrived back to his family, he was a young man of twenty years. Patrick continued to study Christianity.

After making his escape, Saint Patrick, who wasn’t a saint then, made his way back to Britain, but Ireland beckoned him, and he would eventually go back there. Patrick had a vision a few years after returning home, “I saw a man coming, as it were from Ireland. His name was Victoricus, and he carried many letters, and he gave  me one of them. I read the heading: ‘The Voice of the Irish,’ As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea, and they cried out, as with one voice: ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.'” A.B.E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of Saint Patrick’s vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396. However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees. I guess we will ever really know.

me one of them. I read the heading: ‘The Voice of the Irish,’ As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea, and they cried out, as with one voice: ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.'” A.B.E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of Saint Patrick’s vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396. However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees. I guess we will ever really know.

Acting on his vision, Patrick returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary, and that is how he became a patron saint of Ireland. Saint Patrick actually never used a four-leaf clover, but rather he used a three-leaf clover as a way to help people to understand the Trinity (Triune God – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

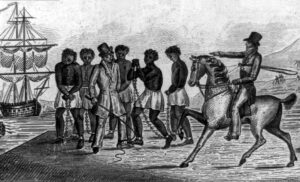

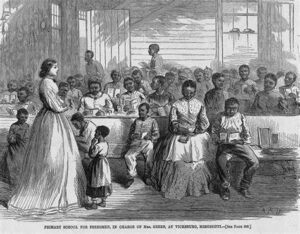

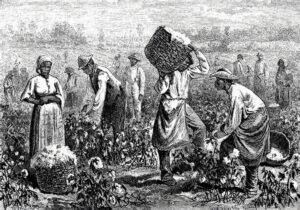

The years of slavery were awful for the African people who were sold into slavery by their own families or their countrymen. They were often stolen in the middle of the night, never to be in their homes again. Some of these slaves were young…some were even children. The terror must have been horrific. Nevertheless, it was what it was. Their life as they knew it was over. The journey to their new “home” was a hard one, and many people didn’t make it. That didn’t matter either, except in the revenue lost…they cared about that.

The years of slavery were awful for the African people who were sold into slavery by their own families or their countrymen. They were often stolen in the middle of the night, never to be in their homes again. Some of these slaves were young…some were even children. The terror must have been horrific. Nevertheless, it was what it was. Their life as they knew it was over. The journey to their new “home” was a hard one, and many people didn’t make it. That didn’t matter either, except in the revenue lost…they cared about that.

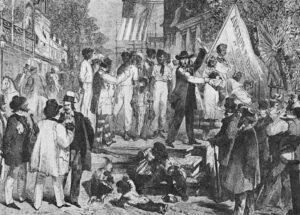

When the slaves arrived in the colonies, they didn’t have last names, or if they did, no one could really understand the last names. That didn’t matter to the slave sellers or the new master, because once sold, the slaves were given the last name of their masters, if they were given one at all. They were non-people. One must also understand that not all slaves were African. Many slaves came from Ireland too, but

I suppose it was easier to get away from their masters, because they were white too…not that they escaped, because where would they go. They were far away from their home too.

In those days, in Colonial America, slaves could win their freedom through lawsuits. I’m not sure what made them think they had a chance of winning their freedom. First of all, they had no money to get an attorney, and no attorney would have taken the case anyway. They had no way of proving their case, and what would their case have been? There was no code of conduct when it came to slaves. They could be beaten, raped, and even killed by their master. They could be overworked, under fed, and punished at will. There really was no case that could be made…as far as I can see anyway. As I said, there was a slim chance that a slave could bring a case, and even less chance that case. Nevertheless, even with that low chance of succeeding, winning in court meant

that the slave was now a citizen. They were free, and no one could dispute that again…legally anyway. The problem now was that these slaves had no last name, and they needed a last name to be a citizen. I seriously doubt they wanted to keep their master’s name. So, to solve the problem, the slaves were given the surname…Freeman. In my genealogist’s mind, there is no greater was to lose the true line of a family than such a name change.

that the slave was now a citizen. They were free, and no one could dispute that again…legally anyway. The problem now was that these slaves had no last name, and they needed a last name to be a citizen. I seriously doubt they wanted to keep their master’s name. So, to solve the problem, the slaves were given the surname…Freeman. In my genealogist’s mind, there is no greater was to lose the true line of a family than such a name change.

Switzerland has long been a neutral nation when it comes to wars other conflicts. That hasn’t always been an easy status to accomplish. According to the Hague Convention of 1907, a neutral country means that the country has declared nonparticipation during a war and cannot be counted on to help fight a belligerent country. “Non-belligerent” countries are ones that offer non-combative support in times of war. Countries interpret neutrality differently. Switzerland has what would be called armed neutrality in global affairs. Switzerland is not alone in that status, since Ireland, Austria, and Costa Rica all take similar non-interventionist stances, but Switzerland remains the oldest and most respected.

Switzerland has long been a neutral nation when it comes to wars other conflicts. That hasn’t always been an easy status to accomplish. According to the Hague Convention of 1907, a neutral country means that the country has declared nonparticipation during a war and cannot be counted on to help fight a belligerent country. “Non-belligerent” countries are ones that offer non-combative support in times of war. Countries interpret neutrality differently. Switzerland has what would be called armed neutrality in global affairs. Switzerland is not alone in that status, since Ireland, Austria, and Costa Rica all take similar non-interventionist stances, but Switzerland remains the oldest and most respected.

The desired neutrality in Switzerland started back in 1515, when the Swiss Confederacy suffered a devastating loss to the French at the Battle of Marignano. Apparently, they really lost their taste for war following the defeat, because the Confederacy completely abandoned its expansionist policies and did everything in their power to avoid any future conflict in the interest of self-preservation. No one likes a war, but I don’t think that many nations detest it so much that they would go to such extremes. While the Battle of Marignano began the desire for neutrality, it was the Napoleonic Wars, that truly sealed Switzerland’s place as a neutral nation. Switzerland was invaded by France in 1798 and later made a satellite of Napoleon Bonaparte’s empire, forcing it to compromise its neutrality. With Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the major European powers decided that a neutral Switzerland might actually be a good thing. Given the volatility of the area they decided that Switzerland would serve as a valuable buffer zone between France and Austria and contribute to stability in the region. I’m not sure how they figured that, considering the fact that they would not fight. Nevertheless, during 1815’s Congress of Vienna, they signed a declaration affirming Switzerland’s “perpetual neutrality” within the international community. Switzerland had what it wanted, as did the international community.

Attaining neutrality and keeping it can be two very different things. Nevertheless, Switzerland maintained its impartial stance through World War I, when it mobilized its army and accepted refugees, also still refusing to take sides militarily. The newly formed League of Nations officially recognized Swiss neutrality and established its headquarters in Geneva in 1920. World War II presented a more significant challenge to Swiss neutrality, when the country found itself encircled by the Axis powers. For a country that no longer had a desire to fight, this was a big problem. Switzerland was able, with threats of retaliation, to maintain its independence. Switzerland also continued to trade with Nazi Germany, a decision that later proved controversial after the war ended, and one they most likely regretted.

Switzerland has taken a more active role in international affairs by aiding with humanitarian initiatives since World War II, but it fiercely maintains its neutral status with regard to military affairs. Switzerland has never joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the European Union, and only joined the United Nations in 2002. Despite its longstanding neutrality, the country still maintains an army for defense purposes and requires part-time military service from all males between the ages of 18 and 34. It always best to be prepared…just in case.

By the time Spring arrives, people are naturally over the cold and sometimes depressing Winter months. When April 1st arrives, hopefully bringing with it, sunshine and warmer temperatures, pranks seem to just pop into our heads. We need a laugh, and the good-natured pranking of our friends is a great way to get that laugh. People have pranked their friends and family in many ways. The ways are really as diverse as the prankster. My sisters and I, when we were little, did all the kid pranks, like “there’s a spider in your hair” or exchanging the salt for the sugar. Other people go all out, like telling someone their car was stolen or placing a rubber snake in their bed. I suppose some pranks can be a little over the top, and can even backfire on the prankster, but most are done good naturedly, and are taken as such. Of course, the best part for the prankster is yelling, “April Fool” to their victim.

By the time Spring arrives, people are naturally over the cold and sometimes depressing Winter months. When April 1st arrives, hopefully bringing with it, sunshine and warmer temperatures, pranks seem to just pop into our heads. We need a laugh, and the good-natured pranking of our friends is a great way to get that laugh. People have pranked their friends and family in many ways. The ways are really as diverse as the prankster. My sisters and I, when we were little, did all the kid pranks, like “there’s a spider in your hair” or exchanging the salt for the sugar. Other people go all out, like telling someone their car was stolen or placing a rubber snake in their bed. I suppose some pranks can be a little over the top, and can even backfire on the prankster, but most are done good naturedly, and are taken as such. Of course, the best part for the prankster is yelling, “April Fool” to their victim.

As traditions go, some stand out more than others. In the United Kingdom, it is tradition that all pranks stopped at noon. This continues to be the custom, with the pranking ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks. So, a person who didn’t watch the time, an playing a prank after midday is considered the “April fool” themselves. In Ireland, it is more of a “fools errand.” The prankster entrusts the victim with an “important letter” to be given to a named person. That person would read the letter, then ask the victim to take it to someone else, and so on. The letter, when opened contained the words “send the fool further” and then the victim knew he had been had. I can’t say that would be a traditional joke, because the word would get around pretty quickly, and then it wouldn’t work.

April Fools’ Day isn’t just for individuals either. On April Fools’ Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and TV stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations. One of the more famous pranks was in 1957, the BBC broadcast a film in their Panorama current affairs series purporting to show Swiss farmers picking freshly-grown spaghetti, in what they called the Swiss Spaghetti Harvest. The BBC

was soon flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day. A good prankster could come up with similar pranks for the media to use, and now with the Internet and readily available global news services, April Fools’ pranks can catch and embarrass more people than ever before. It’s the one day that “fake news” can be fake and it’s ok. Happy April Fools’ Day to all the pranksters out there. Have fun, and watch the time so you don’t wind up being the “fool” indeed.

was soon flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day. A good prankster could come up with similar pranks for the media to use, and now with the Internet and readily available global news services, April Fools’ pranks can catch and embarrass more people than ever before. It’s the one day that “fake news” can be fake and it’s ok. Happy April Fools’ Day to all the pranksters out there. Have fun, and watch the time so you don’t wind up being the “fool” indeed.

Shergar was a racehorse with the possibility for a great future as a stud horse following his 1981 retirement, but that future was cut short on February 8, 1983, when he was stolen. Shergar was born on March 3, 1978. He was an Irish-bred, British-trained thoroughbred racehorse. Shergar’s owner, The Aga Khan, sent the horse for training in Britain in 1979 and 1980. Shergar began his first season of racing in September 1980 and ran two races that year. He won one and came second in the other. Then, in 1981 he ran in six races, winning five of them. He was an amazing horse. In June that year, he won the 202nd Epsom Derby by ten lengths, which is the longest winning margin in the race’s history. Three weeks later he won the Irish Sweeps Derby by four lengths; a month after that he won the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes by four lengths. In his final race of the year he came in fourth, and the Aga Khan took the decision to retire him to stud in Ireland. I suppose that like many sports, there is a short window of opportunity with a racehorse, although it seems to me that Shergar had a very short career, but a promising future in stud service to breed racehorses.

Shergar was a racehorse with the possibility for a great future as a stud horse following his 1981 retirement, but that future was cut short on February 8, 1983, when he was stolen. Shergar was born on March 3, 1978. He was an Irish-bred, British-trained thoroughbred racehorse. Shergar’s owner, The Aga Khan, sent the horse for training in Britain in 1979 and 1980. Shergar began his first season of racing in September 1980 and ran two races that year. He won one and came second in the other. Then, in 1981 he ran in six races, winning five of them. He was an amazing horse. In June that year, he won the 202nd Epsom Derby by ten lengths, which is the longest winning margin in the race’s history. Three weeks later he won the Irish Sweeps Derby by four lengths; a month after that he won the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes by four lengths. In his final race of the year he came in fourth, and the Aga Khan took the decision to retire him to stud in Ireland. I suppose that like many sports, there is a short window of opportunity with a racehorse, although it seems to me that Shergar had a very short career, but a promising future in stud service to breed racehorses.

In 1981 he was retired to what was then the Ballymany Stud in County Kildare, Ireland. Then, in 1983 he was stolen from the stud, and a ransom of £2 million was demanded. The ransom was not paid, and soon the negotiations were broken off by the thieves. In 1999 a confidential informant, formerly in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), stated that they stole the horse. The IRA has never admitted any role in the theft. After Shergar’s Epsom Derby win, the Aga Khan sold 40 shares in the horse, valuing it at £10 million. Retaining six shares, he created an owners’ syndicate with the remaining 34 members. Shergar was stolen from the Aga Khan’s stud farm by an armed gang on February 8, 1983. Negotiations were conducted with the thieves, but the gang broke off all communication after four days when the syndicate did not accept as truth the proof they provided that the horse was still alive. In 1999 Sean O’Callaghan, a former member of the IRA and probably the confidential informant, published details of the theft and stated that it was an IRA operation to raise money for arms. He said that very soon after the theft, Shergar panicked and damaged his leg, which led to him being killed by the gang. An investigation by The Sunday Telegraph concluded that the horse was shot four days after the theft, or right at the time they stopped negotiations.

Whatever happened to Shergar, there have never been any arrests in the case. Shergar’s body has never been recovered or identified. Some people think it is likely that the body was buried near Aughnasheelin, near Ballinamore, County Leitrim. The Shergar Cup was inaugurated in 1999 in honor of Shergar. His story has been made into movies, several books, and two documentaries. Shergar was a great horse, and should have been allowed to live out his life, but people who only wanted to make money to to buy arms, in an effort to bring mass destruction, couldn’t allow this beautiful horse to live. Anytime a horse is stolen, it is traumatic for the horse. Their schedule is disrupted, they don’t know the people who are taking care of them now, and it is possible that care is not what it should be. The panic that happened to poor Shergar should never have happened. I have no doubt they killed that poor horse, but we will never know for sure.

There is a tradition in England and a few other nations like Canada and Ireland, that takes place the day after Christmas, called Boxing Day. It is an odd name for a holiday, but I think the purpose of the holiday far outweighs the name of the holiday. People might argue the original purpose of the holiday, but the most straightforward answer as to what it is about would be that, “We are a little greedy here in the England and Ireland in wanting a more extended holiday. It is not enough for us to have only Christmas Day celebrations, we have added to this another event called Boxing Day.” That might be one part of the picture, but the full answer is not that simple. But firstly, it has nothing to do with the sport of boxing.

There is a tradition in England and a few other nations like Canada and Ireland, that takes place the day after Christmas, called Boxing Day. It is an odd name for a holiday, but I think the purpose of the holiday far outweighs the name of the holiday. People might argue the original purpose of the holiday, but the most straightforward answer as to what it is about would be that, “We are a little greedy here in the England and Ireland in wanting a more extended holiday. It is not enough for us to have only Christmas Day celebrations, we have added to this another event called Boxing Day.” That might be one part of the picture, but the full answer is not that simple. But firstly, it has nothing to do with the sport of boxing.

Boxing Day is a national Bank Holiday. It is a day to spend with family and friends and to eat up all the leftovers of Christmas Day, but there is more to it than that. The origins of the day are filled with history and tradition. People have long disputed the origins of the name Boxing Day. The name is actually a reference to holiday gifts. A “Christmas Box” in Britain is a name for a Christmas present. Boxing Day was traditionally a day off for the servants and the day when they received a “Christmas Box” from the master. The servants would also go home on Boxing Day to give “Christmas Boxes” to their families.

Traditionally, a box to collect money for the poor was placed in churches on Christmas day. The boxes were  opened the next day…Boxing Day. The name refers to a nautical tradition. Great sailing ships when setting sail would have a sealed box containing money on board for good luck. Were the voyage a success, the box was given to a priest, opened at Christmas and the contents then given to the poor. Boxing Day is the 26th December is a national holiday in England and Ireland.

opened the next day…Boxing Day. The name refers to a nautical tradition. Great sailing ships when setting sail would have a sealed box containing money on board for good luck. Were the voyage a success, the box was given to a priest, opened at Christmas and the contents then given to the poor. Boxing Day is the 26th December is a national holiday in England and Ireland.

Boxing Day is a time to spend with family or friends, but usually not those seen on Christmas Day itself. In recent times, the day has begun to include many sports. Horse racing is particularly popular with meets all over the country. Many top football teams also play on Boxing Day. Boxing Day is a time when the British show their eccentric side by taking part in all kinds of silly activities. Bizarre traditions include swimming the icy cold English Channel, fun runs, and charity events. Until 2004, Boxing Day hunts were a traditional part of the day, but the ban on fox hunting has put an end to this in its usual sense. Hunters will still gather dressed resplendently in red hunting coats to the sound of the hunting horn. But, since it is now forbidden to chase the fox with dogs, they now follow artificially laid trails.

Another “sport” to emerge in recent years is shopping. Sadly, what was once a day of relaxation and family time sees the start of the sales. Sales used to start in January, post-New Year, but the desire to grab a bargain and for shops to off-load stock means many now begin on Boxing Day. This tradition makes me especially sad, because it is like Black Friday. By moving Black Friday shopping to Thanksgiving, and now post Christmas sales to Boxing Day, have soured many people to shopping on these days, and the whole purpose is defeated.

In Ireland, Boxing Day is also known as “Saint Stephen’s Day” named after the Saint stoned to death for believing in Jesus. In Ireland on Boxing, there was once a barbaric act carried out by the so-called “Wren Boys.” These boys would dress up and go out, and stone wren birds to death then carry their catch around the town knocking on doors and asking for money, the stoning representing what had happened to Saint Stephen. This terrible tradition has now stopped, thank goodness, but the Wrens Boys still dress up. Now, instead they parade around town and collect money for charity. I’m thankful that such a barbaric tradition, has now taken on a new look, and is now used for good.