indians

We have long known that my sister, Cheryl Masterson’s family is related to the notorious Bat Masterson…gunfighter, gambler, lawman, and well-known Old West character, but I didn’t really know very much about Bat Masterson. William Barclay “Bat” Masterson was born on November 26, 1853 in Iberville County, Quebec, Canada. His father, Thomas Masterson was born in Canada and by occupation was a farmer. His mother, Catherine McGurk, was an immigrant of Ireland. Bat was the second child in a family of five brothers and two sisters. They were raised on farms in Quebec, New York, and Illinois, until they finally settled near Wichita, Kansas in 1871. During his boyhood years he became an expert in the use of firearms, and accompanied expeditions that went out to hunt buffalo.

We have long known that my sister, Cheryl Masterson’s family is related to the notorious Bat Masterson…gunfighter, gambler, lawman, and well-known Old West character, but I didn’t really know very much about Bat Masterson. William Barclay “Bat” Masterson was born on November 26, 1853 in Iberville County, Quebec, Canada. His father, Thomas Masterson was born in Canada and by occupation was a farmer. His mother, Catherine McGurk, was an immigrant of Ireland. Bat was the second child in a family of five brothers and two sisters. They were raised on farms in Quebec, New York, and Illinois, until they finally settled near Wichita, Kansas in 1871. During his boyhood years he became an expert in the use of firearms, and accompanied expeditions that went out to hunt buffalo.

In the Fall of 1871, when Bat was 18 years old, he and his 19 year old brother, Ed decided to head west to Kansas, looking for adventure by hunting buffalo. During this time, they camped with hunters working along the Salt Fork River in what is present day Comanche and Barber Counties in Kansas. It was during their visits to other buffalo hunting camps that the brothers met several men who would also become legends in western history, including Wyatt Earp, Billy Dixon, Tom Nixon, and “Prairie Dog” Dave Morrow.

Bat Masterson was one of the very few who lived during the lawless days of the Old West who wasn’t there to make a name for himself, or to count the notches on his belt. In reality, he was a genuine and honest man, who didn’t have a reputation for violence, but was loyal to the end, and would defend his friends, if necessary. The nickname “Bat” was given to him by his companions one day while out on one of these hunting trips, the name coming from Baptiste Brown, or “Old Bat,” whose fame as a leader, hunter, and trapper was well known in the generation that preceded Masterson upon the Western stage.

In the summer of 1872, Bat and Ed worked on a construction crew that was expanding the Santa Fe railroad to Colorado. That winter, they returned to buffalo hunting and were joined by their younger brother, Jim in their camp along Kiowa Creek southeast of Dodge City. In January, 1873, the Masterson brothers gave up buffalo hunting. Bat remained in Dodge City, but his brothers returned to the family farm in Sedgwick County, Kansas. Ed, after deciding that farming really wasn’t for him, was soon back in Dodge…just a month later, in fact. Ed went to work in the Alhambra Saloon. For a time, Bat returned to buffalo hunting, but the number of buffalo were becoming fewer and fewer. By 1874, the vast numbers of buffalo roaming Kansas had been slaughtered, so many of the hunters moved south and west into what was hostile Indian Territory.

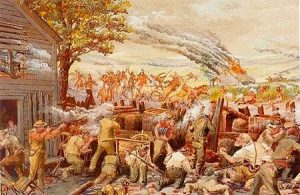

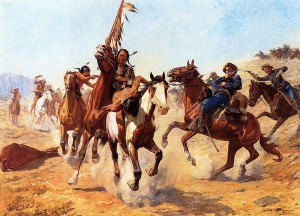

While this venture would prove profitable, the Indians tribes in the area correctly perceived the post and the buffalo hunting as a major threat to their existence and attacks were being made on some buffalo hunters. The hostile environment didn’t stop Adobe Walls saloon owner, James Hanrahan, from leading a party of Dodge City buffalo hunters, including Bat Masterson, southward on June 5, 1874. Along the way, a band of Cheyenne Indians ran off their cattle stock about 75 miles southwest of Dodge City. The hunters soon joined a wagon train en route to Adobe Walls, arriving just hours before the Indian attack, known as the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, took place.

Early in the morning of June 27, 1874, a combined force of some 700 Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho warriors, led by Comanche Chief Quanah Parker and Isa-tai, attacked the buffalo camp. The 28 men, including Bat Masterson and Billy Dixon, took refuge in the two stores and the saloon. Despite being dramatically outnumbered, the hunters’ superior weapons repelled the Indian assault. After four days of continuous battle, about 100 men arrived to reinforce the post and the Indians soon retreated. Loss numbers vary, but as many as 70 Indians were killed and many others, including Parker, were wounded. The men at Adobe Walls suffered four fatalities.

Of course, the attacks brought retaliation in the form of an expedition against the Indians of the Texas Panhandle in what would become known as the Red River War. Masterson joined the expedition that was order by Colonel Nelson A. Miles, as a civilian scout and a teamster working out of Fort Elliot in what was then called Sweetwater, Texas (now Mobeetie). However, the next spring he was back to buffalo hunting and spending time at his friend Charlie Rath’s store, located about five miles from the fort, which had become the “headquarters” for the buffalo hunters. He was also a frequent visitor to the many saloons in the area. By early 1876, he was working as a faro dealer in Henry Fleming’s Saloon.

On January 24th, he became embroiled in an argument with Sergeant Melvin A. King over a card game and a dance hall beauty named Mollie Brennan. The argument quickly led to a gunplay and King was left dead. However, in the melee, King’s shot passed through Mollie Brennan’s body, killing her, and then hit Masterson in the pelvis. The injury caused Bat to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. After he recovered, Masterson returned to Dodge City, Kansas where he became a lawman along with his friend Wyatt Earp under Ford County Sheriff, Charles Bassett. These were the years that Dodge City was known as a “wicked little town.” Cattle drives had replaced the buffalo hunters as longhorn cattle were driven up from Texas along the western branch of the Chisholm Trail to the railroad. For the next ten years, over 5 million head were driven on the trail into Dodge City.

In July, 1877, Bat was appointed under-sheriff of Ford County under Sheriff Charlie Bassett. That very same month, his brother Ed Masterson became an assistant marshal in Dodge City. Just a few months later, in October, Bat announced in the Dodge City Times that he was a candidate for sheriff of Ford County, stating: “At the earnest request of many citizens of Ford County, I have consented to run for the office of sheriff, at the coming election in this county. While earnestly soliciting the suffrages of the people, I have no pledges to make, as pledges are usually considered, before election, to be mere clap-trap. I desire to say to the voting public that I am no politician and shall make no combinations that would be likely to, in anywise, hamper me in  the discharge of the duties of the office, and, should I be elected, will put forth my best efforts to so discharge the duties of the office that those voting for me shall have no occasion to regret having done so. Respectfully, W. B. Masterson.”

the discharge of the duties of the office, and, should I be elected, will put forth my best efforts to so discharge the duties of the office that those voting for me shall have no occasion to regret having done so. Respectfully, W. B. Masterson.”

Masterson never again fought a gun battle in his life after the battle with King, but the story of the Dodge City shootout and his other exploits ensured Masterson’s lasting fame as an icon of the Old West. He spent the next four decades of his life working as sheriff, operating saloons, and eventually trying his hand as a newspaperman in New York City. The old gunfighter finally died of a heart attack in October 1921 at his desk in New York City. He had certainly lived an interesting life.

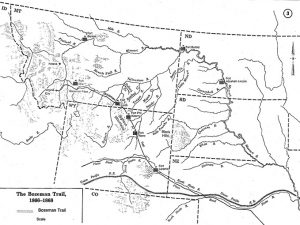

The move west to settle America was seldom a peaceful move. These days we think of loading up our car, and moving to a new city…done and easy, but it wasn’t so back then. There were outlaws, Indians, and unknown perils that could end a trip west, almost before it got started. There were a number of trails commonly used to get to the gold fields in the west, but the Bozeman Trail was one of the most violent, quarrelsome, and ultimately failed experiments in American frontier history. The trail was named for John Bozeman, an emigrant from Georgia, who was said to have blazed the route, but in actuality, the Indians had been using the route as a travel corridor for centuries. Nevertheless, John Bozeman did play a part in the trail. In 1863, Bozeman and partner, John Jacobs widened this corridor for use as a wagon road. They were following in much the same footsteps as Captain William Raynolds had four years earlier in a mapping and exploration expedition for the Army Corps of Topographic Engineers. The plan was to make the trail a shortcut to the goldfields in and around Virginia City, Montana territory. The Bozeman route split off of the Oregon Trail in central Wyoming. Then it skirted the Bighorn Mountains, crossed several rivers including the Bighorn, then traversed mountainous terrain into western Montana. The trail follows a very similar route to the current roads that meander through Wyoming today. The Bozeman trail had several advantages, including an abundant supply of water along with the most direct route to the goldfields, making it the go to trail of that era.

The move west to settle America was seldom a peaceful move. These days we think of loading up our car, and moving to a new city…done and easy, but it wasn’t so back then. There were outlaws, Indians, and unknown perils that could end a trip west, almost before it got started. There were a number of trails commonly used to get to the gold fields in the west, but the Bozeman Trail was one of the most violent, quarrelsome, and ultimately failed experiments in American frontier history. The trail was named for John Bozeman, an emigrant from Georgia, who was said to have blazed the route, but in actuality, the Indians had been using the route as a travel corridor for centuries. Nevertheless, John Bozeman did play a part in the trail. In 1863, Bozeman and partner, John Jacobs widened this corridor for use as a wagon road. They were following in much the same footsteps as Captain William Raynolds had four years earlier in a mapping and exploration expedition for the Army Corps of Topographic Engineers. The plan was to make the trail a shortcut to the goldfields in and around Virginia City, Montana territory. The Bozeman route split off of the Oregon Trail in central Wyoming. Then it skirted the Bighorn Mountains, crossed several rivers including the Bighorn, then traversed mountainous terrain into western Montana. The trail follows a very similar route to the current roads that meander through Wyoming today. The Bozeman trail had several advantages, including an abundant supply of water along with the most direct route to the goldfields, making it the go to trail of that era.

Still, the trail had one major drawback. It cut through the heart of territory that had been promised to several Indian tribes by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1848, making the people traveling the trail…the outlaws. The area included the rich hunting grounds of the Powder River Country, claimed by the Sioux and other tribes. They were not feeling very hospitable about these “white men” traipsing through their hunting grounds, killing their animals, and running off many in the herds. Nevertheless, the first emigrant trains began traveling up the trail not long after Bozeman and Jacobs had finished marking the route. In 1864, a large train of 2,000 settlers  successfully made the trek. This was the high point of travel along the corridor. Though some wagon trains were successful after that, there were constant threats of attack. Over the next two years travel along the corridor came to a complete halt because of numerous raids by a coalition of tribes.

successfully made the trek. This was the high point of travel along the corridor. Though some wagon trains were successful after that, there were constant threats of attack. Over the next two years travel along the corridor came to a complete halt because of numerous raids by a coalition of tribes.

Then the people started to put pressure on the United States government to protect the travelers. In 1866, United States Army troops were dispatched to construct three forts along the trail, which would supposedly offer protection to wagon trains. These posts, running from south to north, were Forts Reno, Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith. Ominously, each of these forts was named after a general that had died during the just completed Civil War. Somehow that doesn’t seem to instill a lot of hope…at least to me. With the installation of the forts, the trail had, in effect become a military road. The protection afforded by the United States Army presence enraged the tribes. With that intervention came a two year conflict, known as Red Cloud’s War. Under the leadership of Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud, raids and ambushes were carried out against soldiers, civilians, supply trains and anyone else who dared to attempt the trail.

Three famous skirmishes were The Fetterman Massacre, in December, 1866, in which an army detachment of 79 soldiers and 2 civilians led by Captain William Fetterman were lured from Fort Phil Kearney and ambushed within a few miles of the fort. On August 1, 1867, the Hayfield Fight, where 19 soldiers and 6 civilians detailed for guard and hay cutting duty were attacked. The Indians held them under siege for over 8 hours, but they managed to hold off 500 hundred warriors until help arrived. And finally, The Wagon Box Fight, where a detachment of 31 soldiers sent out to guard a team of wood cutters, was encircled. They fought off numerous attacks over a five hour period from hundreds of warriors. These continued raids and skirmishes were the rule that proved that peace was not going to be the reality they had hoped. Life guarding the trail was a  combination of tension, monotony, and loneliness. Soldiers on the verge of mutiny and even cases of insanity, deserted their posts. With few, if any, emigrants using the trail, because they were too afraid, the army sequestered behind fortress walls and tribes showing few signs of easing up on attacks. Finally, the United States government decided to pursue a peace policy. The second (1868) Fort Laramie Treaty recognized the Powder River Country once again as the hunting territory of the Lakota and their allies. A presidential proclamation was issued to abandon the forts. The Bozeman Trail was history, and for the first time, the United States government had lost a war. What a shock that must have been for our nation.

combination of tension, monotony, and loneliness. Soldiers on the verge of mutiny and even cases of insanity, deserted their posts. With few, if any, emigrants using the trail, because they were too afraid, the army sequestered behind fortress walls and tribes showing few signs of easing up on attacks. Finally, the United States government decided to pursue a peace policy. The second (1868) Fort Laramie Treaty recognized the Powder River Country once again as the hunting territory of the Lakota and their allies. A presidential proclamation was issued to abandon the forts. The Bozeman Trail was history, and for the first time, the United States government had lost a war. What a shock that must have been for our nation.

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

The Dakota Indians were often referred to as the Sioux, which I did not know was a derogatory name derived from part of a French word meaning “little snake.” It almost makes it seem like they were talking badly about them to their face, but so they couldn’t understand it. The government treated the Dakota poorly, and the Dakota saw their hunting lands dwindling  down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

On August 17, the situation exploded when four young Dakota warriors returning from an unsuccessful hunt, stopped to steal some eggs from a white settlement. The were caught and they picked a fight with the hen’s owner. The encounter turned tragic when the Dakotas killed five members of the family. Now, the Dakota knew that they would be attacked. Dakota leaders, knew that war was at hand, so they seized the initiative. Led by Taoyateduta, also known as Little Crow, the Dakota attacked local agencies and the settlement of New  Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

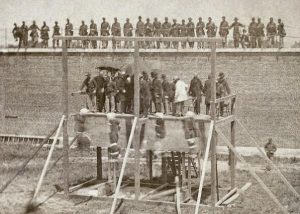

President Abraham Lincoln dispatched General John Pope, fresh from his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Pope was to organize the Military Department of the Northwest. Some of the Dakota immediately fled Minnesota for North Dakota, but more than 2,000 were rounded up and over 300 warriors were sentenced to death. President Lincoln commuted most of their sentences, but on December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were executed at Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest mass execution in American history, and it was all because they were starving, and had no hope of living through that year.

When watching the old western television shows, we are told of the conflicts with the Indians, and how dangerous it was for the settlers to come out to the West, but rarely do we relate that to members of our own family…although I do not know why exactly. For any of us who can trace our roots back to people who moved out west in the 1800s or before, the risk of conflicts with the Indians is a very real part of our family’s past. For the Knox family, of whom my husband, Bob Schulenberg is a member, whether they know it or not, the Indian conflicts became a very real tragedy at one point. Bob’s 6th Great grandmother, Jean Gracey Knox had a brother named Patrick Gracey. Patrick immigrated to America with Jean and her husband, John. After the immigrated, Patrick met and married Rebecca Barnett, and possibly later married a second time to a woman named Hall. Patrick raised a large family, and one of his daughters, whose name is unknown, was scalped by the Indians, along with her baby. I realize that many

When watching the old western television shows, we are told of the conflicts with the Indians, and how dangerous it was for the settlers to come out to the West, but rarely do we relate that to members of our own family…although I do not know why exactly. For any of us who can trace our roots back to people who moved out west in the 1800s or before, the risk of conflicts with the Indians is a very real part of our family’s past. For the Knox family, of whom my husband, Bob Schulenberg is a member, whether they know it or not, the Indian conflicts became a very real tragedy at one point. Bob’s 6th Great grandmother, Jean Gracey Knox had a brother named Patrick Gracey. Patrick immigrated to America with Jean and her husband, John. After the immigrated, Patrick met and married Rebecca Barnett, and possibly later married a second time to a woman named Hall. Patrick raised a large family, and one of his daughters, whose name is unknown, was scalped by the Indians, along with her baby. I realize that many  people were scalped by the Indians, and that there might have been a number of them who were related to my family or to Bob’s, but it somehow seems a little more real and quite unsettling when you know for sure that one of your relatives lost their life this way.

people were scalped by the Indians, and that there might have been a number of them who were related to my family or to Bob’s, but it somehow seems a little more real and quite unsettling when you know for sure that one of your relatives lost their life this way.

The scalp of the enemy was considered a trophy to the Indians. The more scalps, the better the status as a warrior. I suppose that many people would almost look at it as being similar to a serial killer, and maybe in some ways it was, but the Indians were so mad at the White Man for taking land that they felt belonged to them. I suppose it did, but then why couldn’t we all live together in peace. After all, America was and still is considered the melting pot, because we have taken immigrants from many countries to build this nation. Nevertheless, we were not always welcome here, and often it was our own fault for breaking the treaties we put in place.

Still, I cannot imagine a society in which it was acceptable to scalp a person. I suppose though, that the Indian culture wasn’t really a society in the same sense of the world that we think of society. Their beliefs and their practices were much different that those of the White Man. That is part of the reason we considered them savages, but in their eyes, they were brave, and they were fighting for their rights. It was a way of life. It was a necessary evil…at least in their eyes. It was as simple as that.

Until my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to the Seattle area last year, it never occurred to me to wonder how Seattle might have received its name. It had always been Seattle. It seemed like an interesting name, but that was really all it was to me. Nevertheless, whether you know the story or not, the name is not simply interesting. Seattle was actually named after an Indian chief named Seathl. He was the chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes who lived around the Pacific Coast bay that is called the Puget Sound today. He was born about 1780 or 1790, the son of a Suquamish father and a Duwamish mother, a lineage that gave him influence in both tribes.

Until my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to the Seattle area last year, it never occurred to me to wonder how Seattle might have received its name. It had always been Seattle. It seemed like an interesting name, but that was really all it was to me. Nevertheless, whether you know the story or not, the name is not simply interesting. Seattle was actually named after an Indian chief named Seathl. He was the chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes who lived around the Pacific Coast bay that is called the Puget Sound today. He was born about 1780 or 1790, the son of a Suquamish father and a Duwamish mother, a lineage that gave him influence in both tribes.

In the early 1850s, there were small groups of Euro-Americans who started settling along the banks of the Puget Sound. Chief Seathl welcomed these new neighbors, and was known to treat them with kindness. In 1853, the settlers moved to a site on Elliot Bay and established a permanent town there.  Since Chief Seathl had been so nice to them, they named the town after him. I can’t say why the different in the spelling, but to this day it is called Seattle. The site was picked because of the beautiful forest on the bluff behind the new village.

Since Chief Seathl had been so nice to them, they named the town after him. I can’t say why the different in the spelling, but to this day it is called Seattle. The site was picked because of the beautiful forest on the bluff behind the new village.

When the California Gold Rush hit, there came with it, a huge need for timber, and soon most of the villagers were at work cutting the trees and “skidding” them down a long chute to a newly constructed sawmill. The chute became known as “skid road.” Eventually, it became the main street in Seattle…and it kept its original name. When the Seattle business district later moved north, the area became a haven for drunks and derelicts. Consequently, “skid road” or “skid row” became lingo for the dilapidated area of any town. In fact, I don’t know of a big city that doesn’t have a “skid row” somewhere in it.

Many of the Indians in the area were hostile toward the settlers, and war broke out in 1855, but Chief Seathl  argued that resistance to the settlers would only get more people killed. After a time, the other Indians agreed, and the war ended in 1856. Chief Seathl tried to learn the ways of the white man, rather than fight them. Jesuit missionaries introduced him to Catholicism, and he became a devout believer. Many of the people of Seattle respected Chief Seathl and his religion, and they became Catholics too. Then, just thirteen years after the settlers founded the city of Seattle, Chief Seathl died in on June 7, 1866 at the age of 77 or 86 depending on the year of birth that people accept as correct. In a strange tradition, to provide Chief Seattle with a pre-payment for the difficulties he would face in the afterlife, the people of Seattle levied a small tax on themselves to use the chief’s name.

argued that resistance to the settlers would only get more people killed. After a time, the other Indians agreed, and the war ended in 1856. Chief Seathl tried to learn the ways of the white man, rather than fight them. Jesuit missionaries introduced him to Catholicism, and he became a devout believer. Many of the people of Seattle respected Chief Seathl and his religion, and they became Catholics too. Then, just thirteen years after the settlers founded the city of Seattle, Chief Seathl died in on June 7, 1866 at the age of 77 or 86 depending on the year of birth that people accept as correct. In a strange tradition, to provide Chief Seattle with a pre-payment for the difficulties he would face in the afterlife, the people of Seattle levied a small tax on themselves to use the chief’s name.

This summer when Bob and I were in the Black Hills, we were looking around in the gift shop at Mount Rushmore, when I came across a book called “Women’s Diaries Of The Westward Journey.” Since then, I have been thinking about what it must have been like to travel in a covered wagon…especially for a woman. Of course, times were different back then, and people did not have the luxury of a daily shower, or even a real bathroom…and that was in their own homes. So, imagine what life would be like on a wagon, traveling in a wagon train headed west in the mid-1800s. As the emigrants were traveling west, they were making their own roads, hunting their own food, and cooking over a campfire. For a lot of people, I’m sure this sounds like going camping, but then imagine doing it for months at a time. A day’s travel averaged about twelve to twenty miles, meaning that on the plains, they often stopped for the day within sight of the site they had just left that morning. For travelers now, that would seem insanely slow, but for the wagon trains, it was just the normal day’s journey. They knew no other way.

This summer when Bob and I were in the Black Hills, we were looking around in the gift shop at Mount Rushmore, when I came across a book called “Women’s Diaries Of The Westward Journey.” Since then, I have been thinking about what it must have been like to travel in a covered wagon…especially for a woman. Of course, times were different back then, and people did not have the luxury of a daily shower, or even a real bathroom…and that was in their own homes. So, imagine what life would be like on a wagon, traveling in a wagon train headed west in the mid-1800s. As the emigrants were traveling west, they were making their own roads, hunting their own food, and cooking over a campfire. For a lot of people, I’m sure this sounds like going camping, but then imagine doing it for months at a time. A day’s travel averaged about twelve to twenty miles, meaning that on the plains, they often stopped for the day within sight of the site they had just left that morning. For travelers now, that would seem insanely slow, but for the wagon trains, it was just the normal day’s journey. They knew no other way.

People back then would have been somewhat crazy to set out alone for the west…or to set out any later than spring, because either scenario was bound to fail. They needed the protection of the wagon train, as well as the  additional supplies, should a wagon be lost to fire, a river crossing, or an attack by Indians. It was their back up plan. They couldn’t just stop at the next town at a store and buy more supplies. There were no towns, stores, or even roads. When we travel, even in the rural state of Wyoming that I live in, we are used to seeing miles with very little to catch the eye, other that an occasional farm house, and an occasional town, but remember that we have roads to follow so we don’t lose our way. And even then, many of us use GPS to make sure we are taking the right road. They had none of that. They had to use the sun and landmarks to make sure they were going the right direction. They depended on people who had taken this trip before them. It was all they had. I think most of us today would go nuts if we never saw a house, a road, or a town. We would wonder if we were insane for setting out on this crazy adventure at all. One woman wrote to her husband, who was waiting at the end of the line, with the spelling ability she had at the time, “I can tell you nothing only that were hear and its strange I wish we had never started … it seems impossible to get their.” She had set out in a wagon train with her four children, without her husband, and that in itself must have been scary.

additional supplies, should a wagon be lost to fire, a river crossing, or an attack by Indians. It was their back up plan. They couldn’t just stop at the next town at a store and buy more supplies. There were no towns, stores, or even roads. When we travel, even in the rural state of Wyoming that I live in, we are used to seeing miles with very little to catch the eye, other that an occasional farm house, and an occasional town, but remember that we have roads to follow so we don’t lose our way. And even then, many of us use GPS to make sure we are taking the right road. They had none of that. They had to use the sun and landmarks to make sure they were going the right direction. They depended on people who had taken this trip before them. It was all they had. I think most of us today would go nuts if we never saw a house, a road, or a town. We would wonder if we were insane for setting out on this crazy adventure at all. One woman wrote to her husband, who was waiting at the end of the line, with the spelling ability she had at the time, “I can tell you nothing only that were hear and its strange I wish we had never started … it seems impossible to get their.” She had set out in a wagon train with her four children, without her husband, and that in itself must have been scary.

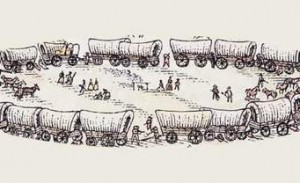

Days on the wagon train began long before dawn with a simple breakfast of coffee, bacon, and dry bread. After breakfast, the people secured their supplies, hitched up their teams, and hit the trail by seven o’clock in the morning. Most people walked because of lack of space, and the fact that the wagon was so uncomfortable. The  train stopped at noon for a cold meal of coffee, beans, and bacon, which had been prepared that morning. During this break, called nooning, men and women would gather and talk, children would play, and animals would rest. After that, the travel would continue until around six o’clock in the evening, when they wagons would circle for the night. Some people would visit after supper, but most went to bed, because they were exhausted. Some slept in the wagon, but most slept on the ground, because oddly enough it was more comfortable. While traveling west on the wagon trains was a necessary journey to be made to grow this country, it was not an easy journey to make, and for that reason, I have to stand in awe of those who did it.

train stopped at noon for a cold meal of coffee, beans, and bacon, which had been prepared that morning. During this break, called nooning, men and women would gather and talk, children would play, and animals would rest. After that, the travel would continue until around six o’clock in the evening, when they wagons would circle for the night. Some people would visit after supper, but most went to bed, because they were exhausted. Some slept in the wagon, but most slept on the ground, because oddly enough it was more comfortable. While traveling west on the wagon trains was a necessary journey to be made to grow this country, it was not an easy journey to make, and for that reason, I have to stand in awe of those who did it.

I don’t always think of myself as living in a historic area, although I should, because during the days of the Old West, at least, much history happened here. In fact, on this day, July 28, 1865, twenty year old Caspar Collins…a gutsy lieutenant from Dogwood Knob and Hillsboro, Ohio led 20 men to fight a battle against 1,000 to 3,000 Indians, just outside Platte Bridge Station, which was near Casper, Wyoming, where I live. The battle had been coming, and everyone knew it. The Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne Indians had been attacking the United States Army for a couple of months now. The Indians had raided outposts and stagecoach stations over a wide area of Wyoming. On this day back in 1865, the Indians assembled their warriors and descended on Platte Bridge Station. The Platte River bridge was guarded by 120 men near the bridge, and another 28 soldiers guarded a wagon train a few miles away. The Indians killed 29 soldiers, while only losing 8 warriors in the raid.

I don’t always think of myself as living in a historic area, although I should, because during the days of the Old West, at least, much history happened here. In fact, on this day, July 28, 1865, twenty year old Caspar Collins…a gutsy lieutenant from Dogwood Knob and Hillsboro, Ohio led 20 men to fight a battle against 1,000 to 3,000 Indians, just outside Platte Bridge Station, which was near Casper, Wyoming, where I live. The battle had been coming, and everyone knew it. The Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne Indians had been attacking the United States Army for a couple of months now. The Indians had raided outposts and stagecoach stations over a wide area of Wyoming. On this day back in 1865, the Indians assembled their warriors and descended on Platte Bridge Station. The Platte River bridge was guarded by 120 men near the bridge, and another 28 soldiers guarded a wagon train a few miles away. The Indians killed 29 soldiers, while only losing 8 warriors in the raid.

In reality, the Army was unprepared for this attack or the ones leading up to it. Colonel Thomas Moonlight had led a 500 Cavalry force out to seek out and punish the raiding Indians on May 26, 1865. He hung to minor Oglala leaders…Two Face and Black Foot. He left them hanging for days. I’m sure this infuriated the Indians. On June 3, the army began to worry that the 1,500 Lakota, mostly Brulé, and Arapaho who were living near Fort Laramie, might become hostile. So they decided to move them about 300 miles east to Fort Kearny in Nebraska. The Indians protested that Fort Kearny was in the territory of their traditional enemies, the Pawnee. The next day, near present day Morrill, Nebraska, most of the Indians refused to accompany the soldiers and  began crossing the North Platte River, assisted by Crazy Horse and a band of Oglalas on the other side. Attempting to stop them, Captain William D. Fouts and four soldiers were killed. Informed of the disaster, Moonlight departed Fort Laramie with 234 cavalry to pursue the Indians. He traveled so fast that many of his men had to turn back because their horses were spent. On June 17, near present day Harrison, Nebraska, the Lakota raided his horse herd and relieved him of most of his remaining horses. Moonlight and his men had to walk 60 miles back to Fort Laramie. He was severely criticized by his soldiers for being drunk and not setting a guard on his horses. On July 7, Moonlight was relieved of his command and mustered out of the army.

began crossing the North Platte River, assisted by Crazy Horse and a band of Oglalas on the other side. Attempting to stop them, Captain William D. Fouts and four soldiers were killed. Informed of the disaster, Moonlight departed Fort Laramie with 234 cavalry to pursue the Indians. He traveled so fast that many of his men had to turn back because their horses were spent. On June 17, near present day Harrison, Nebraska, the Lakota raided his horse herd and relieved him of most of his remaining horses. Moonlight and his men had to walk 60 miles back to Fort Laramie. He was severely criticized by his soldiers for being drunk and not setting a guard on his horses. On July 7, Moonlight was relieved of his command and mustered out of the army.

The Platte River bridge was a key crossing point of the North Platte River for wagon trains of emigrants traveling the Oregon and Bozeman Trails. The Indians wanted to stop traffic on the Bozeman Trail which led through the heart of their hunting territory. The bridge had been constructed in 1859 and was almost 1,000 feet long and 17 feet wide. On July 20, Indian leaders made their final decision to launch an attack against the bridge. The warriors gathered and set out southward from the mouth of Crazy Woman Creek on the Powder River. The Platte River Bridge was 115 miles south. The army was the largest they had ever seen. It was estimated to number 3,000 men. U.S. army accounts state that the wagons were forced into a hollow where they held out for four hours, using fire from Spencer rifles to repel assaults until a large group closed on foot and overwhelmed the defenders, killing all.

Then came the attack of Platte Bridge Station. The battle that left 29 men dead…including Lieutenant Caspar  Collins, and at least 10 more men seriously injured. The battles before had involved maybe 1000 Indians. This battle was different…this one involved 3000. They were seriously outnumbered, but Lieutenant Caspar Collins went out to fight anyway. The day after the battle, the Indian army broke up into small groups and dispersed. A few remained near the Oregon Trail for raiding but most returned to their villages in the Powder River country for their summer buffalo hunt. Indians lacked the resources to keep an army in the field for an extended period of time. The Army officially renamed Platte Bridge Station to Fort Caspar to honor Collins, using his given name to differentiate the post from an existing fort in Colorado named after Collins’ father.

Collins, and at least 10 more men seriously injured. The battles before had involved maybe 1000 Indians. This battle was different…this one involved 3000. They were seriously outnumbered, but Lieutenant Caspar Collins went out to fight anyway. The day after the battle, the Indian army broke up into small groups and dispersed. A few remained near the Oregon Trail for raiding but most returned to their villages in the Powder River country for their summer buffalo hunt. Indians lacked the resources to keep an army in the field for an extended period of time. The Army officially renamed Platte Bridge Station to Fort Caspar to honor Collins, using his given name to differentiate the post from an existing fort in Colorado named after Collins’ father.

My life began in Superior, Wisconsin. Superior is a small town located at the tip of Lake Superior, which is the largest of the Great Lakes. I have always felt close ties to Superior and to Wisconsin, in general, because while I have not lived there since I was three years old, it was the place of my birth, and the place where my Uncle Bill Spencer and his family lived for many years, as well as many of my great grandparents’ family.

My life began in Superior, Wisconsin. Superior is a small town located at the tip of Lake Superior, which is the largest of the Great Lakes. I have always felt close ties to Superior and to Wisconsin, in general, because while I have not lived there since I was three years old, it was the place of my birth, and the place where my Uncle Bill Spencer and his family lived for many years, as well as many of my great grandparents’ family.

In the early years of the area, the Native American Indian Tribes called it home. The first Europeans to live there were the British and French, and the American settlers who lived in Wisconsin when it was a territory. One tribe, the Meskwaki Indians were particularly hostile toward the French, but many of the Indians got along well with the pioneers. The Great Lakes area increased dramatically after the decline of the British influence following the War of 1812. This was a land with a mix of pioneers and Indians. Of course, like most areas, the Indians were eventually placed on reservations.

Like every state in the United States, Wisconsin started as a US Territory, and when there were enough people to make statehood a necessity, each one became a state. Wisconsin initially became a terriroty on this day, April 20, 1836. Initially, it included all of the present-day states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and part of the Dakotas east of the  Missouri River. Much of that territory was part of the Northwest Territory, which was ceded by Britain in 1783. The portion which is now the Dakotas was originally part of the Louisiana Purchase. Eventually, the states would separate their areas, leaving Wisconsin with the area it now occupies.

Missouri River. Much of that territory was part of the Northwest Territory, which was ceded by Britain in 1783. The portion which is now the Dakotas was originally part of the Louisiana Purchase. Eventually, the states would separate their areas, leaving Wisconsin with the area it now occupies.

My people would arrive in the area much later, but many of them would stay in the area of Wisconsin and Minnesota for generations, and even to this day. For me, there will always be a place in my heart for Wisconsin, especially Superior, and the Great Lakes, especially Lake Superior. It is a beautiful area that my family has called home for generations, and I will always love it.

In a war, secrecy is vital. The different sides must take whatever steps necessary to inform their troops and allies of their next step, without revealing the plan to the enemy. In World War II, America and her allies were having trouble with the level of secrecy they were able to achieve. It seemed that no matter what code they used, it was broken almost immediately. It did not help matters that many of the Japanese cryptographers had been educated in the United States. They spoke very good English, and they were very amazingly adept at breaking top secret military codes. For America and her allies, coming up with newer and more complicated codes was becoming more and more difficult, and the Japanese cryptographers seemed to break the new codes almost as quickly as they were developed. They were in real trouble. Then someone remembered a type of code that had been used in World War I, and things began to look up a little for America and the allies. The code was the use of Code Talkers from the Choctaw tribe.

In a war, secrecy is vital. The different sides must take whatever steps necessary to inform their troops and allies of their next step, without revealing the plan to the enemy. In World War II, America and her allies were having trouble with the level of secrecy they were able to achieve. It seemed that no matter what code they used, it was broken almost immediately. It did not help matters that many of the Japanese cryptographers had been educated in the United States. They spoke very good English, and they were very amazingly adept at breaking top secret military codes. For America and her allies, coming up with newer and more complicated codes was becoming more and more difficult, and the Japanese cryptographers seemed to break the new codes almost as quickly as they were developed. They were in real trouble. Then someone remembered a type of code that had been used in World War I, and things began to look up a little for America and the allies. The code was the use of Code Talkers from the Choctaw tribe.

That someone was war analyst Philip Johnston. Phillip, an American who fought in World War I, stationed in France, was too old to fight in World War II, but he wanted to aid in the effort anyway. As a boy, he spent time  on the Navajo Indian Reservation, where his parents were Protestant missionaries. He learned to speak the Navajo language with his playmates. Suddenly, the idea of a secret military code based on the Navajo language made perfect sense to him.

on the Navajo Indian Reservation, where his parents were Protestant missionaries. He learned to speak the Navajo language with his playmates. Suddenly, the idea of a secret military code based on the Navajo language made perfect sense to him.

In mid-April of 1942, Marine recruiting personnel went to the Navajo Reservation, and presented their plan. They enlisted thirty volunteers from the agency schools at Fort Wingate and Shiprock, New Mexico and Fort Defiance, Arizona. It would be a tall order for these volunteers. Each one had to be fluent in Navajo and English, but they also had to be physically fit, because they would be messengers in a combat zone. They were told that they would be specialists in the United States as well as over seas. Some of them were underage, but birth records on the Reservation were not well kept, so it was easy for volunteers to lie about or just not know their true age, and so they could participate. Carl Gorman, a 36-year-old Navajo from Fort Defiance, was too old to be considered by the Marines, so he lied about his age in order to be accepted.

Because the Navajo language was complicated, and due to the many different dialects, the Japanese could  never crack the code. They even captured a Navajo soldier and made him listen to the talk for hours, but because he had not been trained, he was still unable to crack the code. By 1945, there were about 540 Navajos who served in the Marines, and of those 375 to 420 were trained as code talkers. The rest served in other capacities. The code talkers payed an instrumental part in the success of the war effort. On June 4, 2014, Chester Nez, the last living original code talker, passed away. Once, in an interview he said, “My first transmission—one that did not involve coordinates—was one I will always remember: Beh-na-ali-tsosie a-knah-as-donih ah-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi, which translates to: Enemy machine gun nest on your right flank. Destroy.” These were great men, and our nation owes them a debt it can never repay.

never crack the code. They even captured a Navajo soldier and made him listen to the talk for hours, but because he had not been trained, he was still unable to crack the code. By 1945, there were about 540 Navajos who served in the Marines, and of those 375 to 420 were trained as code talkers. The rest served in other capacities. The code talkers payed an instrumental part in the success of the war effort. On June 4, 2014, Chester Nez, the last living original code talker, passed away. Once, in an interview he said, “My first transmission—one that did not involve coordinates—was one I will always remember: Beh-na-ali-tsosie a-knah-as-donih ah-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi, which translates to: Enemy machine gun nest on your right flank. Destroy.” These were great men, and our nation owes them a debt it can never repay.

I often wonder how it must have felt to live in a time when so many things were changing in ways that man had not seen before. Things like the automobile, the airplane, the light bulb, the telephone, and the telegraph, all came into being between the 1800s and the early 1900s. Prior to these things, our world was rather primitive concerning things like travel, communication, and even the home life…at least by today’s standards, anyway.

I often wonder how it must have felt to live in a time when so many things were changing in ways that man had not seen before. Things like the automobile, the airplane, the light bulb, the telephone, and the telegraph, all came into being between the 1800s and the early 1900s. Prior to these things, our world was rather primitive concerning things like travel, communication, and even the home life…at least by today’s standards, anyway.

When families began moving West to find land and adventure, it was often a very sad time, because many of these people would not see their loved ones again. They might not even hear from them. This really seemed like an unacceptable situation for most of the people on both sides of that spectrum. The people needed to hear from their loved ones, and so like every other idea, from necessity came a solution…the Pony Express. Prior to the Pony Express, people might try to send a letter with a wagon train heading West to see of they could manage  to get it to a loved one who had left a year or more before. Imagine the impossibility of that feat. The person with whom the letter was sent, might not even know the person to whom the letter was being sent. It meant asking around in the area they had planned to settle in, and if they had moved elsewhere…well that is the real definition of the dead letter.

to get it to a loved one who had left a year or more before. Imagine the impossibility of that feat. The person with whom the letter was sent, might not even know the person to whom the letter was being sent. It meant asking around in the area they had planned to settle in, and if they had moved elsewhere…well that is the real definition of the dead letter.

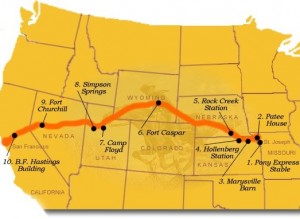

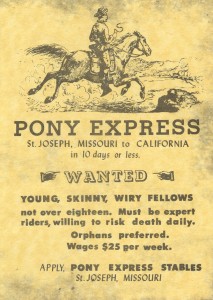

The Pony Express became the first dedicated postal service ever, on this day, April 3, 1860, but it was a far cry from the mail service of today, about which many of us complain. The men who chose to be Pony Express riders had to be told about what they might be riding into. There were Indians, who did not like the White Man. Treaties had been broken, and the White Man was considered an intruder on Indian land. To say that the White Man was not welcome in the West, was putting it mildly. Every time the Pony Express rider set out, he was taking on the risk of never coming back. The Help Wanted posters clearly stated the dangers, and the riders had to be single young men preferably under eighteen and preferably orphans!! Not a glowing help wanted ad, for sure, still there was a need, and these brave men took the challenge and made it work. The Pony Express was a short lived phenomenon, however, lasting just eighteen short months. I suppose something had to be done to make mailing a letter safer. At the point when the last Pony Express rider rode his route, the telegraph had somewhat  taken its place. Most what had been needed was to be able to let people about the death of loved ones and other urgent or important news, so it seemed like an unnecessary risk to place on these men, when a safe way had been found.

taken its place. Most what had been needed was to be able to let people about the death of loved ones and other urgent or important news, so it seemed like an unnecessary risk to place on these men, when a safe way had been found.

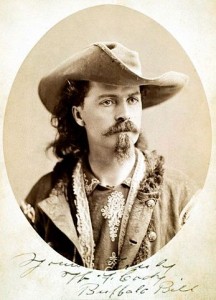

The first Pony Express rider to make the run has been a matter of dispute, but historians have narrowed it down to Johnny Fry or Billy Richardson. James Randall was credited with being the first Eastbound rider, heading out from San Francisco to Sacramento, and William (Sam) Hamilton took the mail from there to the Sportsman Hall Station, where he handed it off to Warren Upson. Other riders were Gus and Charles Cliff, Robert Haslam, Jack Keetley, Billy Tate, and the famous William Cody, known to most of us as Buffalo Bill. Together, these men rode into history as some of the bravest men who ever lived. Riding alone through dangerous territory, risking their lives to make life a little easier for the ever expanding nation we lived in.